Changes in Rural Korean Couples’ Decision-Making Patterns: A Longitudinal Study

Abstract

Korea has experienced ever-increasing numbers of women entering the labor force. Rural families particularly are impacted by these transitions, which may shift family dynamics and power, as evidenced in couples’ decision-making patterns. This longitudinal panel study of 1,870 rural Korean farm and nonfarm households in 2000, 2005, and 2009 examines the degree to which couples’ decision-making practices changed during the decade along three dimensions: agricultural work, family life, and domestic work. Wives in farm households significantly increased their participation in joint decision-making in agricultural work and family life. However, money management decisions remained mostly with husbands in both farm and nonfarm households. Husbands’ participation in domestic work decision-making was unchanged, even though they increased their involvement in childcare and house cleaning. Implications are offered for policy makers and practitioners working with rural Korean families on the benefits of women’s empowerment and equality in couples’ decision-making.

Keywords:

rural Korea, couples’ decision-making, gender rolesIntroduction

Men and women in most parts of the world experience a socially determined division of work roles. These socially constructed roles are often unequal in power and decision-making, in control over assets and events, in freedom of action, and in ownership of resources. Many studies identify family life tasks in and outside the home either as men’s tasks or as women’s tasks (Bokemeier & Garkovich, 1987; Damisa & Yohanna, 2007; Doss, 1999; Manda & Mvumi, 2010). Yet in actual practice, these gender-based divisions have blurred in many industrialized countries over the last few decades. Both men and women are involved in all types of family life tasks.

In South Korea, the gender-based division of family life tasks appears to be changing dramatically owing to modernization, industrialization, and economic development. However, in rural areas, the division of tasks has changed less dramatically for farm wives even though many farm families rely on wives’ labor to manage their farms (Cho, 2002). Changes in the structure of Korean agriculture during the early 2000s contributed to greater involvement of women in agricultural and economic activities in rural areas. Rural women’s labor participation in farming increased twofold over the 35-year period from 28% in 1970 to 52% in 2006 (Kang, 2008) as farm families changed their primary crops from rice to cash crops, such as fruit, vegetables, and floriculture to achieve higher financial benefits. The number of female farmers increased from 47.8% in 2000 to 59.5% in 2009, whereas the percentage of male farmers decreased (Korean Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, 2009).

Simultaneously, there has been an increase in the number of small businesses run by farm wives, either individually or as members of cooperatives. Many farm wives are involved in off-farm employment to supplement their family income, and their labor and income contribute to the maintenance of both the farm and family life. Their labor force participation and hourly earnings were higher than their husbands in 2005 (Statistics Korea, 2005).

Women’s farm and off-farm labor traditionally has not been paid. Rather, it was taken for granted as a contribution to the family (Cho, 2002). Some researchers observed that women still are not rewarded for their contributions and are excluded from decision-making (Bokemeier & Garkovich, 1987; Cho, 2002; Damisa & Yohanna, 2007; Eun, 2009; Kang, 2009; Park, 2005; Stickney & Konrad, 2007). Their roles in the agricultural sector and family life are seen only as supportive, even though more and more of them are labor force participants and substantial contributors to the farm and to their family’s income. With rural women’s labor and economic activities, the increase in their participation in these areas appears to be associated with an increase in their involvement in decision-making (Anthopoulou, 2010; Bokemeier & Garkovich, 1987; Cho, 2002; Damisa & Yohanna, 2007; Kang, 2008; Kang, 2009; Kim, G. M., 2004; Whatmore, 1991).

The Korean government has taken steps to boost rural women’s participation in business development as a way to enhance the rural economy. Governmental policies and the Rural Development Administration (RDA) helped rural women find additional income through diverse economic or agricultural activities outside of their domestic work (e.g., employment education and support for childcare facilities) (Korean Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, 2001). This rural reconstruction has brought new opportunities for rural women since 2000. For example, the profit-sharing based Family Agreement of Farm Management (FAFM) was intended to enhance women’s participation in farm management. According to K. M. Kim (2004), the FAFM increased women’s responsibility, satisfaction, and self-esteem. Women’s paid labor helped to increase their power and reduce their gender-based tasks in family living (Eun, 2009; Heo, 2008; Stickney & Konrad, 2007). Given that more and more rural women participate in diverse activities like on-/off-farm paid work, small farm businesses, or tourism, the RDA is assessing how rural couples make decisions regarding family life, domestic tasks, and agricultural tasks (Anthopoulou, 2010; O’Toole & Macgarvey, 2003).

Additionally, researchers have recommended that women farmers’ status and participation in decision-making be increased as their roles as farm producers have become more important (Cho, 2002; Choi, 2001; Kang, 2008; Park, 2005). For example, Park (2005) noted that over 47% of agricultural labor was being managed by women. The researchers argued that as women become more involved in decision-making on their family farms, their power would likely increase.

Given the increase in farm wives’ agricultural/industrial labor force participation and the out-migration of youth for education or work, how has the gender-based division of family life tasks changed in rural Korea? Are there differences between how rural farm couples make decisions and rural nonfarm couples make them? Do rural couples make decisions differently based on the types or dimensions of family life? The purpose of this study is to examine how rural Korean couples’ family life decision-making may be undergoing changes. This study examines rural Korean couples’ joint decision-making and their gender-based division of tasks. The study determines the degree of joint decision-making by a panel of rural couples between 2000 and 2009 on three dimensions: agricultural work, family life, and domestic work.

Rural Korean Gender Roles

Gender roles are conceptually linked to tasks of men and women, with different relative perceived value. The work in which women engage, whether inside or outside the home, is often valued less than the work in which men engage (Deseran & Simpkins, 1991). Common in many Korean families, men work as breadwinners and women work as homemakers. The man’s role is regarded as more important than the woman’s role (Eun, 2009; Heo, 2008).

Whatmore (1991) argued that to understand the position of women as farm wives requires a theory of gender relations as power relations. In rural areas especially, a man (husband) is the representative of a family and has the authority to decide family property, farming, and family life, even if a woman (wife) works in or outside the home every day (Cho, 2002). Rural husbands usually do not have egalitarian concepts of sharing power and position with their wives. Their gender-role attitudes are conservative with regard to sharing domestic work, decision-making, and caring for their parents or children (Heo, 2008; RDA, 1997) even though, over time, men and women throughout Korea have become more egalitarian in their work and public lives (Eun, 2009).

As an increasing number of rural women work outside the home and participate in family farming, social and cultural expectations have created a dilemma in gender roles (Bokemeier & Garkovich, 1987; Choi, 2001; Damisa & Yohanna, 2007; Deseran & Simpkins, 1991). Rural wives’ labor in the home and on the farm has been taken for granted by their husbands (Cho, 2002; Kang, 2008). Domestic work is still the wife’s responsibility even if she is paid for work outside of their family farm. Eun (2009) claimed that women generally work more hours than men when domestic household work is included, regardless of their paid work. Women’s participation in family farming, domestic work, and, increasingly, off-farm work becomes a large burden (Bokemeier & Garkovich, 1987; Damisa & Yohanna, 2007; Kang, 2009; Park, 2005). Nevertheless, women’s off-farm work has brought about gradual changes in their household tasks and farm-related decision-making (Cho, 2002).

Men’s non-participation in domestic work is considered normal and in accord with conservative gender roles. Men’s patriarchal practices and attitudes based on gender division reveal the inequality of labor participation in the family, and the non-sharing of power and decision-making with their wives (Bokemeier & Garkovich, 1987; Eun, 2009; Heo, 2008; Whatmore, 1991). Domestic work is still a rural woman’s responsibility even if she is paid for work outside of their family farm. However, Deseran and Simpkins (1991) discovered that the allocation of rural family’s domestic tasks was not influenced by husbands’ gender-role attitudes, but rather by their occupational type, regardless of their wives’ work outside the home. Similarly, in a study of married couples from 28 countries, Stickney and Konrad (2007) found that men’s occupations are strongly correlated with their gender-role attitudes. Men with higher-skilled, higher-paid occupations had significantly more egalitarian gender-role attitudes, but there was no difference in the amount of household labor they performed, whether or not they held these attitudes.

On the other hand, Manda and Mvumi (2010) have argued that women’s labor hours most strongly affected men’s involvement in domestic household work. Men’s non-participation in domestic work is considered normal given conservative gender roles. However, as women increased their paid work hours, men also increased their household work hours (Eun, 2009). Men’s patriarchal attitudes based on gender reveal the inequality of labor participation in the family, and the non-sharing of power and decision-making with their wives (Bokemeier & Garkovich, 1987; Eun, 2009; Heo, 2008; Whatmore, 1991).

Decision-Making and Gender Roles

Gender roles and marital equity are influenced by decision-making (Bartley, Blanton, & Gilliard, 2005). According to Blood and Wolfe (1960), power relations between wives and husbands are explained by the decision-making processes they experience. Decision-making has been endorsed frequently as a measure of relationship equality in the family sociology literature (Rosenbluth, Steil, & Whitcomb, 1998). Whereas equal sharing in decision-making appears to be most beneficial for relationships overall (Bartley et al., 2005), decision-making has been divided along traditional gender roles, with wives making decisions concerning day-to-day details of family life and husbands making the major decisions, such as those concerning resource allocation (Bartley, et al., 2005; Steil & Weltman, 1991).

A study conducted by the RDA (RDA, 1997) found that improvements of women’s status in rural households could be explained by the change in power relations between spouses. The study found that couples made joint decisions on domestic affairs related to children and family life. However, husbands made most of the decisions related to farming (Cho, 2002; Choi, 2001). Choi (2001) found a clear, gender-based division of labor both inside and outside of the home, although the couples had more discussions in order to make decisions.

Women farmers with higher economic quality of life appear to be more likely to participate in agricultural decision-making (Gasson & Winter, 1992; Haugen, 2004; Whatmore, 1991) as well as domestic work decision-making (Choi, 2001; Haugen, 2004; Park, 2005). Cho’s (2002) study summarized previous research conducted over three decades (1960–1990) in Korea about rural women’s participation in the family decision-making process. That study, which focused primarily on agriculture, examined changes in women’s labor participation and the number of hours devoted to farm work. Cho concluded that women farmers have become more involved in decision-making and have expanded the areas in which they engaged in decision-making with their husbands over the last three decades. However, she reported that rural women remained limited in certain areas of decision-making, such as buying and selling farm land or purchasing farm machinery. These women’s decision-making power was not strong considering how much they contributed to farm labor even though joint decision-making between rural couples had increased.

A growing consensus of the research literature suggests that couples’ decision-making equality increases as wives enter the labor force and obtain incomes outside the home. Additionally, the census data show that rural Korean wives’ off-farm labor force participation has been steadily increasing. A differentiation may be made in rural households between those whose primary economic activity and income source is directly related to agricultural production (rural farm couples) and those whose primary activity and income source is related to other businesses even though they may derive some income from farming (rural nonfarm couples). It would follow that both rural farm couples and rural nonfarm couples have engaged in increasing amounts of joint decision-making over the decade. It is hypothesized that the rate of increase between 2000 and 2009 in joint decision-making for rural farm couples is substantial but will be less so for nonfarm couples. These increases in joint decision-making for farm couples are expected particularly on the dimensions of agricultural work and family life. Given the ideological nature of rural households, it is hypothesized that couples’ joint decision-making on the dimension of domestic work has not increased significantly, particularly among farm couples.

Method

This study examines how the decision-making process has changed between rural husbands and wives in both farm and nonfarm households during the 10-year period of 2000 through 2009 in 187 rural areas. Specifically, the study explores how rural women’s involvements and power in decision-making have changed on three dimensions: agricultural work, family life, and domestic work.

This study used data from the Survey on the Rural Living Indicators conducted by the RDA in Korea since 2000. Longitudinal data were collected three times (November 2000, 2005, and 2009) from a panel of couples in rural areas. The panel consisted of a survey of the same individuals for each of the three data points. The RDA has continued to administer the longitudinal survey since 2009, however without the items pertaining to gender-based decision-making. Thus, these three iterations of the survey have particular significance as the data are nowhere else available. The Korean National Statistical Office’s 2000 Population and Housing Census enumeration districts (EDs) were used as the first stage in a multi-stage cluster sampling design. The EDs consisted of clusters of community districts, which comprise Eup (towns) or Myen (remote rural villages). Ten households were selected by stratified sampling from each of 187 community districts, which were selected from 12 EDs. Data were collected from both the husband and wife in the same household simultaneously by one of the RDA’s rural living monitors (RLM); each RLM typically surveyed the selected households in one or two villages. The cluster sampling design resulted in the selection of a sample of 1,870 rural households in 2000. Some householders were excluded from the original household panels because of attrition (response rejected, moved, or householders passed away). This exclusion reduced the size of the original household panels to 1,870 in 2000, 1,651 in 2005, and 1,450 in 2009. Measures of gender-based decision-making were based on survey self-report, not on independent observation of multiple cultural frames of gender roles, negating triangulated verification. The survey was administered to the husband and wife simultaneously, which increased the likelihood of common responses from the perspective of the husband and wife. As shown in similar studies (e.g., Choi, 2001), given the conservative nature of husbands’ responses, the simultaneous data collection could slightly skew both husbands’ and wives’ responses to a more conservative position than they actually hold.

Characteristics of the Participants

The socio-demographic characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. Descriptive results show there were twice as many farm households as nonfarm households in the survey. Farm households’ primary economic activity and the largest proportion of their total household income is from the production of raw agricultural materials (e.g., rice, cabbage, peppers, etc.). Although nonfarm households may engage in agricultural production, their primary economic activity and the largest proportion of their total household income is from employment in nonfarm businesses such as value-added agricultural manufacturing, rural tourism, or seasonal construction. The percentage of participants who resided in remote rural villages (Myen) declined slightly compared with those who lived in a town (Eup), the percentage of which increased over the 10 years. Over half of the participants (68.2%) were in farm households in 2000, and that percentage increased to 73.9% in 2009. The residents’ average age level increased over the 10 years. Similarly, according to the census, the average ages of rural men and women in 2000 were 38.1 and 43.4, respectively; they were 44.7% and 50.3%, respectively, in 2010. The percentage of people under age 39 dropped from 263 (15.0%) in 2000 to 36 (2.5%) in 2009. However, the percentage of those over age 70 increased by more than 15 percentage points. The percentage of families consisting of three or more generations decreased from 335 (18.0%) in 2000 to 194 (13.4%) in 2009, whereas the percentage of single-generation households increased during the 10-year period. The growth in the number of foreign-born wives in rural Korea is a relatively new phenomenon and was not a demographic variable when the panel was created in 2000.

Data Collection and Analysis

Nationwide surveys were conducted in 2000, 2005, and 2009 by the RDA using a panel sample. The purpose of the surveys was to observe long-term changes in rural life and suggest policies to enhance the quality of life in rural Korea. The joint decision-making processes of couples were examined through structured interviews. Couples were asked to rate their degree of joint decision-making on 12 variables on the three dimensions of agricultural work, family life, and domestic work. Agricultural work variables included buying and selling land and houses, selling farm products, and money management. Family life variables were household expenses, choosing TV channels, managing children’s education, caring for children, deciding on donations, and associating with relatives. The variables of cooking and dishwashing, laundry, and cleaning house comprised the domestic work dimension. A 5-point Likert scale was used: 1 = fully husband; 2 = generally husband; 3 = together; 4 = generally wife; and 5 = fully wife.

The responses from the participants were used in the analysis to find the changes and trends in the joint decision-making processes of the couples. ANOVA and Duncan post hoc tests were used to compare the couples’ joint decision-making scores over time (2000, 2005, and 2009) for each of the variables on the three dimensions. The scores for the farm and nonfarm household couples were analyzed independently.

Results

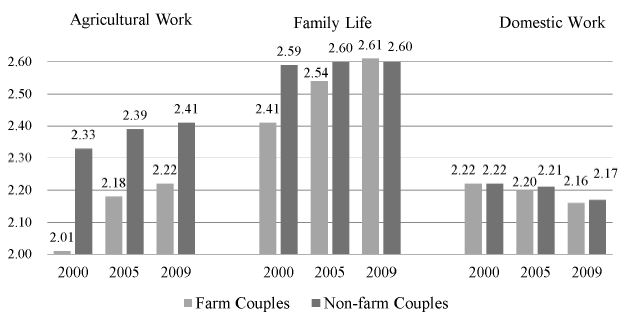

The degree to which farm and nonfarm couples engage in joint decision-making was compared for the years 2000, 2005, and 2009 in the dimensions of agricultural work, family life, and domestic work. It was hypothesized that both rural farm couples and rural nonfarm couples engage in increasing amounts of joint decision-making as graphically illustrated in Figure 1. Index scores (weighted averages) were computed for rural farm and for rural nonfarm couples’ joint decision-making scales in agricultural work, family life, and domestic work. Shifts can be seen in decision-making from generally husband (2) toward together (3) for agricultural work and family life. For each year, both farm and nonfarm couples appear to increase in joint decision-making. However, dramatic increases were seen among farm couples as their scores began to approach those of nonfarm couples. The scores most closely approaching joint decision-making were on the dimension of domestic work. The scores for the farm and nonfarm couples were very nearly the same and appear to be relatively unchanged during the decade. The specific items comprising the agricultural work, family life, and domestic work dimensions for the farm and nonfarm couples are examined next.

Index scores comparing rural farm and nonfarm couples’ joint decisionmaking in agricultural work, family life, and domestic workNote: 1 = fully husband; 2 = generally husband; 3 = together; 4 = generally wife; 5 = fully wife.

As Table 2 shows, statistically significant shifts were noted toward greater equality over time in decision-making concerning agricultural work in farm households: buying and selling land and house (F = 25.036, p < .001); selling farm products (F = 22.670, p < .001); and money management (F = 4.302, p < .05). The most notable shifts occurred between 2000 and 2005 based on the Duncan post hoc tests. A substantial shift toward greater joint decision-making occurred in buying and selling land and houses (M = 2.11 in 2000; M = 2.39 in 2009), and selling farm products during the decade (M = 2.11 in 2000; M = 2.39 in 2009). Although a shift occurred over time in money management (1.54 in 2000; M = 1.64 in 2009), the variable remains primarily a husband’s domain. Similarly, husbands in nonfarm households slightly increased their decision-making in selling farm products (M = 3.00 in 2000; M = 2.87 in 2005; F = 6.116, p < .01).

There were no statistically significant shifts toward greater equality over time in agricultural work decision-making in nonfarm households. Figure 1 illustrates the change over time in an index of agricultural work decision-making for farm and nonfarm households. Although the nonfarm household joint decision-making scores remained relatively flat between 2000 and 2009, the nonfarm household scores were on average higher than the farm household scores.

A shift toward great equality occurred over time in family life joint decision-making for farm household couples (Table 3). Statistically significant differences were found for each variable on this dimension: household expenses (F = 11.535, p < .001), choosing TV channels (F = 10.330, p < .001), managing children’s education (F = 6.524, p < .05), associating with relatives (F = 13.937, p < .001), and deciding donations (F = 54.707, p < .001). Notably, the couples in farm households mostly decided generally husband on choosing TV channels (M = 2.70 in 2000; M = 2.11 in 2009), but together for managing children’s education (M = 2.87 in 2000; M = 2.99 in 2009). With a shift toward more egalitarian decision-making over the decade, men’s dominance in making family life decisions diminished slightly overall, but not in all specific behaviors. Husbands in farm households continue to predominate (2 = generally husband) over the years in decisions related to household expenses; however, there was a noticeable shift toward greater joint decision-making on this variable (M = 2.00 in 2000; M = 2.11 in 2009). Farm household couples also show substantial shifts over the decade toward joint decision-making when deciding on donations (M = 2.21 in 2000; M = 2.61 in 2009) and associating with relatives (M = 2.24 in 2000; M = 2.45 in 2009). Couples in nonfarm households reportedly have been making joint family life decisions since 2000. Their scores typically were in the range of 3.00 (together) and show no statistically significant changes over the decade.

Concerning domestic work, husbands in farm households slightly increased their decision-making in cooking and dishwashing (M = 2.09 in 2000; M = 2.05 in 2009; F = 3.035, p < .05) and laundry work (M = 2.09 in 2000; M = 2.07 in 2009; F = 3.321, p < .01) (Table 4). Similarly, husbands in nonfarm households slightly diminished their decision-making in house cleaning (M = 2.12 in 2000; M = 2.22 in 2005; F = 3.266; p < .05). Decision-making in cooking, dish washing, and laundry work was usually shared between spouses in both farm- and nonfarm households, and did not significantly change over the decade. In general, nonfarm couples practiced more joint decision-making than nonfarm couples in most domestic work variables.

Discussion

Couples’ decision-making processes affect many facets of life for rural Korean husbands and wives. At one level, the decision-making process involves the allocation of tasks. It also represents the relations by which couples exercise their power and control over the means of production and the products of family labor. Additionally, decision-making affects gender roles and the responsibilities of couples that have been strongly influenced by patriarchal culture. The findings of this study demonstrate that decision-making processes between rural Korean couples appear to be undergoing slow, subtle, but steady changes. These findings support the emerging research literature on the topic (e.g., Cho, 2002; Choi, 2001). The shifts in couples’ decision-making processes appear to be occurring simultaneously with broader modernization transitions that were taking place across the nation during the decade 2000–2009.

Such transitions include the expansion of economic activities associated with commercialized farming and women’s increased participation in the labor force, both on- and off-farm, over the past decade. In light of these transitions, this study examined the ways in which rural Korean couples’ joint decision-making has changed on the dimensions of agricultural work, family life, and domestic work.

Agricultural Work

The findings of this study are consistent with the findings of other studies demonstrating a tendency toward more joint decision-making on the dimension of agricultural work (e.g., Cho, 2002; Damisa & Yohanna, 2007; Kang, 2008). However, the present study extends the literature by noting the tendency for more joint decision-making on the dimensions of family life and domestic work. The findings partially support the hypothesis that both rural farm couples and rural nonfarm couples would engage in increasing amounts of joint decision-making; changes were seen primarily among farm couples with relatively few changes evident among nonfarm couples. Joint decision-making among rural farm couples showed movement from the generally husband toward the together levels on the agricultural work and family life dimensions, whereas these levels for rural nonfarm couples remained relatively stable, although higher than those of the rural farm couples. As hypothesized, joint decision-making in the domestic work dimension remained nearly unchanged at the generally husband level for both rural farm and rural nonfarm couples.

A growing body of literature has emerged regarding household financial decision-making (Bernasek & Bajtelsmit, 2002; Elder & Rudolph, 2003; Qualls, 1987). For example, Hanna and Lindamood (2016), in examining a sample of U.S. households, analyzed which spouse was the more financially knowledgeable and presumably, therefore, had responsibility for household finances (e.g., cash flow and credit management, savings, and investments). Using variables from a household production model (which spouse has a comparative advantage) and a bargaining model (which spouse has power based on gender roles), they found household income and net worth were key determinants of financial knowledgeability. These findings suggest that comparative advantage factors, such as increased education, is less a driver of financial decision-making in the U.S. than other socio-cultural factors. The present study found subtle, but significant shifts toward greater equitability in financial decision-making (specifically, buying and selling land and houses, selling farm products, money management, household expenses, and deciding donations), particularly among rural Korean farm couples. Thus, cultural shifts, as well as power derived from increases in education and income, will be needed if the movement toward joint decision-making among rural Korean couples is to continue.

Korean agriculture has been structured by cultural factors such as gender, farm businesses, and small family farms. Traditionally, husbands in rural households exerted dominant decision-making power, whereas their wives played supportive or subordinate roles. Agricultural work had been organized patriarchally owing to cultural norms, even though farm wives often worked an increasing number of hours on farms or farm-related activities. Previous research concluded that farm wives exercised less power over major farm business decisions or day-to-day management (e.g., Berlan-Darque, 1988; Damisa & Yohanna, 2007; Gasson & Winter, 1992; Stickney & Konrad, 2007).

However, this study finds that husbands in farm households are expressing growing support for joint decision-making concerning agricultural work. Couples have been moving toward more joint decision-making on the dimension of agricultural work over the last 10 years. Thus, wives in farm households are increasing their decision-making power and involvement in agricultural work.

Family Life

Rural wives may use their on-farm labor and economic activities to control decision-making over both farm work and family resources. With the exception of associating with relatives and deciding on donations, rural couples practiced joint decision-making in family life. From a patriarchal Korean cultural perspective, this finding may be explained by wives’ relationships with their in-laws. Rural family members may still rely on the husband’s decisions in this area (Cho, 2002).

By extending the trajectory of change in couples’ decision-making found in this study, couples’ decision-making will likely become more shared as women’s roles and economic activities develop further and as men’s attitudes change regarding gender roles. Assuming that more young people and women leave rural areas, couples’ joint decision-making will be increasingly essential as a catalyst to change gender-role attitudes regarding shared household work and power equality between husbands and wives. Couples’ joint decision-making has the potential to improve the economic and social well-being of their families, given the small, family farm structure and family-based businesses that exist in rural Korea. For women farmers to remain active in the farm businesses, the restructuring of gender roles and the redistribution of power within farm households will be critical.

Domestic Work

Given the traditional nature of rural households, couples’ joint decision-making on the dimension of domestic work was not expected to increase significantly, particularly among farm couples. This study found support for that expectation in that few statistically significant increases were found. If increases occurred, they may perhaps have happened prior to the decade studied. Rural nonfarm husbands’ participation in domestic decision-making remained relatively unchanged even though they slightly increased their decision-making involvement in childcare and house cleaning.

These findings must also be understood in light of interplay between demographic and cultural changes taking place in rural Korea. As noted above, the average ages of rural men and women increased substantially during the period between 2000 and 2010. This demographic shift is the result of a declining birth rate, out-migration of younger residents, and a generational shift. With fewer traditional cultural ideologies being held by younger generations (Choi, 2001), more egalitarian attitudes regarding gender roles may be emerging. Nevertheless, the scores for variables on the domestic work decision-making dimension remain solidly in the generally husband range both for rural farm and rural nonfarm couples. Which spouse makes decisions for the activities in this dimension and which spouse actually does these activities may be quite different–an anomaly. It may be anticipated that gender-based domestic activities remain a deeply embedded cultural norm. Additional research is needed to examine this anomaly.

Another demographic change pertains to the growing number of foreign-born spouses, particularly rural wives (Kim, 2009). The impact of these spouses on couples’ decision-making will likely be affected by many factors, including nationality and culture. Whereas some of these individuals may hold equal power and egalitarian gender roles (Haugen, 2004), others may not, all of which has health, education, income, and life chances implications (Chang, 2016). With industrial diversification to include rural tourism and value-added food processing, as well as production agriculture, a diversity of gender roles may also be available. Again, additional research is needed to examine these critical demographic shifts.

Although rural gender-role attitudes tend to be more traditional regarding domestic work and caring for parents or children, the process of modernization throughout Korea has resulted in more egalitarian roles both in the public and private spheres. Choe (2006) has shown that factors related to modernization and development, such as reductions in fertility rates, increased age of marriage, and increases in educational levels among women. These shifts are related to attitudinal change regarding marriage and family life (Lee, Kim, Park, Oh, & Park, 2006). As women engage in employment outside the home, shared decision-making and responsibilities may become an even greater necessity.

Conclusions

Traditionally, family life and domestic labor were the domains of women, whereas agricultural work was the domain of men. This study found that rural Korean couples’ decision-making patterns related to agricultural work, family life, and domestic activities are becoming more egalitarian, although these shifts are gradual and subtle. These results can guide other researchers and governmental officials to review policies related to rural families, rural education programs, the structure of agriculture, and new forms of rural business management, such as the Family Agreement of Farm Management (Kim, K. M., 2004). The findings that subtle shifts are occurring in rural couples’ decision-making patterns can help local organizations identify how to communicate with families regarding farming, education, and family welfare. For rural couples, this study reinforces the expansion in joint decision-making with regard to farming, family life, and domestic work.

Gender divisions in decision-making appear to be somewhat less rigid in many places in rural Korea as women enter arenas traditionally dominated by men. As a result, following the process of modernization, a trend toward greater joint decision-making by rural couples is slowly but steadily occurring. Enhancing women’s power in joint decision-making can benefit the economic and social well-being of rural Korean families, as well as the nation (Kim, G. M., 2004).

Small businesses run by women that produce local, traditional agro-foods or family farm tourism are beginning to flourish in the Korean countryside. As rural women participate in business or obtain off-farm employment, it is important to determine how these women make business-related decisions. Additional research is needed to discover how these women operate their businesses, how their income levels change, and how their professional careers progress.

Rural women’s participation in joint decision-making may empower them by improving their legal and economic status. Educational programs may be useful to help women and their husbands explore the evolution of family farming structures. These programs could assist rural husbands and wives to share decision-making power equally in agriculture, family life, and domestic work dimensions. Empowering rural women economically and politically will transform them from playing invisible, subordinate roles to assuming roles of leadership and active community membership. Rather than being untapped resources, rural women will be positioned to use their abilities for local development, the benefit of their families, and the betterment of their communities.

The primary limitations of this study need to be addressed. Data are based on the respondent couples’ self-reported experiences. Although changes took place throughout rural Korea during the decade when data were collected (2000–2009), community-specific changes (e.g., demographic and ethnic change, agro-technology changes, employment change, etc.) could not be linked directly to the couples. Additional studies are needed to show how macro-level and community/regional-level factors directly affect changes at the household-level.

This study examined changes in decision-making patterns over time for rural farm and rural nonfarm couples. As noted, multiple shifts toward egalitarian decision-making were found for rural farm couples; relatively few were noted for rural nonfarm couples. Various factors may affect farm couples’ decision-making patterns (e.g., couples’ ages, spousal ethnicity, number of generations in the home, education and training, off-farm labor force participation, etc.). These factors have important implications for practitioners and policymakers. Further research would provide insights into if and how these factors interact with couples’ decision-making patterns.

Statistically significant changes in rural couples’ decision-making patterns were evident, particularly for rural farm couples, during the decade of 2000 –2009. For example, farm household couples’ mean averages in decision-making shifted from 2.11 to 2.31 to 2.39 for 2000, 2005, and 2009, respectively. Using the 5-point scale with 2 = generally husband and 3 = together, these scores, although moving toward together, remain in the generally husband range. Such small increments of change could suggest a very limited practical change despite being statistically significant. Alternatively, the small increments over the decade could also suggest that socio-cultural change involving gender roles can be slow and that more dramatic change would be evident over several decades. Follow-up longitudinal studies are needed to determine the degree to which the shift to more egalitarian decision-making has continued.

References

-

Anthopoulou, T., (2010), Rural women in local agrofood production: Between entrepreneurial initiatives and family strategies. A case study in Greece, Journal of Rural Studies, 26(4), p394-403.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2010.03.004]

-

Bartley, S. J., Blanton, P. W., & Gilliard, J. L., (2005), Husbands and wives in dual-earner marriages: Decision-making, gender role attitudes, division of household labor, and equity, Marriage & Family Review, 37(4), p69-94.

[https://doi.org/10.1300/j002v37n04_05]

- Berlan-Darque, M., (1988), The division of labour and decision-making in farming couples: Power and negotiation, Sociologia Ruralis, 28(4), p271-292.

- Bernasek, A., & Bajtelsmit, V. J., (2002), Predictors of women’s involvement in household financial decision-making, Financial Counseling and Planning, 13(2), p39-47.

- Blood, R. O. Jr., & Wolfe, D. M., (1960), Husbands and wives: The dynamics of family living, Oxford, England, Free Press Glencoe.

- Bokemeier, J., & Garkovich, L., (1987), Assessing the influence of farm women’s self-identity on task allocation and decision making, Rural Sociology, 52(1), p13-36.

-

Chang, H. C., (2016), Marital power dynamics and well-being of marriage migrants, Journal of Family Issues, 37(14), p1994-2020.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513x15570317]

- Cho, H. K., (2002), The change of agricultural labor participation and decision-making involvement of rural women in Korea from 1960s to 1990s, Journal of Korean Home Management Association, 20(1), p75-86, (In Korean).

- Choe, M. K., (2006), Modernization, gender roles and marriage behavior in South Korea, In Y. S. Chang, & S. H. Lee (Eds.), Transformations in twentieth century Korea, p291-309, London, Routledge.

- Choi, K. R., (2001), Sex-role attitude, conjugal status level and status satisfaction of married women living in Korean rural area, Journal of Korean Home Management Association, 19(3), p53-72, (In Korean).

- Damisa, M., & Yohanna, M., (2007), Role of rural women in farm management decision making process: Ordered probit analysis, World Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 3(4), p543-546.

-

Deseran, F., & Simpkins, N., (1991), Women’s off-farm work and gender stratification, Journal of Rural Studies, 7(1/2), p91-97.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0743-0167(91)90047-v]

- Doss, C. R., (1999), Twenty-five years of research on women farmers in Africa: Lessons and implications for agricultural research institutions––With an annotated bibliography, (CIMMYT Economics Program Paper No. 99-02), El Batán, Mexico: International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT).

- Elder, H. W., & Rudolph, P. M., (2003), Who makes the financial decisions in the households of older Americans?, Financial Services Review, 12(4), p293-308.

- Eun, K. S., (2009), Household division of labor for married men and women in Korea, Korea Journal of Population, 32(3), p145-171.

-

Gasson, R., & Winter, M., (1992), Gender relations and farm household pluriactivity, Journal of Rural Studies, 8(4), p387-397.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0743-0167(92)90052-8]

- Hanna, S. D., & Lindamood, S., (2016), Household investments: Still a man’s world? Working Paper, Retrieved January 12, 2017, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/294876089_Household_Investments_Still_a_Man’s_World.

- Haugen, M. S., (2004), Rural women’s employment opportunities and constraints: The Norwegian case, In H. Buller & , & K. Hoggart (Eds.), Women in the European countryside, p59-82, Burlingto, VT, Ashgate.

- Heo, S. Y., (2008), Research on time use for housework of women and men in double income households, Journal of Korean Women’s Studies, 24(3), p177-210, (In Korean).

- Kang, H. J., (2008), Factors affect women farmers’ economic activities, Journal of Rural Development, 31(4), p69-81, (In Korean).

- Kang, H. J., (2009), An analysis of the opportunity cost of Korean women farmers, Journal of Rural Development, 31(6), p63-77, (In Korean).

-

Kim, A. E., (2009), Global migration and South Korea: Foreign workers, foreign brides and the making of a multicultural society, Ethnic and Race Studies, 32(1), p70-92.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870802044197]

- Kim, G. M., (2004), Improving women farmers’ roles, Rural Policy Review, 11, p91-125.

- Kim, K. M., (2004), Development of policies for women farmers by their role types in Korea, K. M. Kim (Ed.), Design of counterplans to support women’s agricultural activities in Korea, p3-63, Suwon, Korea, Rural Development Administration, (In Korean).

- Lee, S. S., Kim, T. H., Park, S. M., Oh, Y. H., & Park, H. J., (2006), 2005 national survey on marriage and fertility dynamics, Gacheon, Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs, (In Korean).

- Korean Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, (2001), Analysis of gender roles in agricultural policy, Gacheon, Korea, Korean Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, (In Korean).

- Korean Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, 2009, Statistics on women farmers., Seoul, Korea, Korean Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, Retrieved December 17, 2016, from http://woman.maf.go.kr (In Korean).

-

Manda, J., & Mvumi, B. M., (2010), Gender relations in household grain storage management and marketing: The case of Binga District, Zimbabwe, Agriculture and Human Values, 27(1), p85-103.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-008-9171-8]

- O’Toole, K., & Macgarvey, A., (2003), Rural women and local economic development in south-west Victoria, Journal of Rural Studies, 19(2), p173-186.

- Park, J. G., (2005), Differences of women farmers’ quality of life according to agricultural and housework activities and the conditions of their health management, Journal of Rural Development, 28(4), p33-49, (In Korean).

-

Qualls, W. J., (1987), Household decision behavior: The impact of husbands and wives sex role orientation, Journal of Consumer Research, 14(2), p264-279.

[https://doi.org/10.1086/209111]

-

Rosenbluth, S. C., Steil, J. M., & Whitcomb, J. H., (1998), Marital equality: What does it mean?, Journal of Family Issues, 19(3), p227-244.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/019251398019003001]

- Rural Development Administration (RDA), (1997), The characteristics of domestic work and its satisfaction, Suwon, Korea, Rural Resource Development Institute, Rural Development Administration, (In Korean).

- Statistics Korea, (2005), Census of agriculture, forestry, and fisheries, Daejeon, Korea, National Statistical Office, Retrieved December 17, 2016, from http://kosis.go.kr (In Korean).

- Steil, J. M., & Weltman, K., (1991), Marital inequality: The importance of resources, personal attributes, and social norms on career valuing and allocation of domestic responsibilities, Sex Roles, 24, p161-179.

-

Stickney, L., & Konrad, A., (2007), Gender-role attitudes and earnings: A multinational study of married women and men, Sex Roles, 57, p801-811.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9311-4]

-

Whatmore, S., (1991), Life cycle or patriarchy? Gender divisions in family farming, Journal of Rural Studies, 7(1/2), p71-76.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0743-0167(91)90043-r]

Biographical Note: Duk-Byeong Park is an Associate Professor in the Department of Community Development at Kongju National University, Korea. He is the chief editor of the Journal of Agricultural Extension and Community Development. His research interests involve rural community and economic development, rural tourism, the role of women in rural community leadership, and children and immigration. His current research articles have appeared in the International Journal of Tourism Research, the Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Management, and Educational Studies. E-mail: parkdb84@kongju.ac.kr

Biographical Note: Gary A. Goreham is a Professor in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at North Dakota State University, USA. He is the editor of the Encyclopedia of Rural America: The Land and the People. His research involves rural community economic development, the role of women in rural community leadership, and the use of the community capitals framework in communities recovering from natural disasters. He works with students to examine the assets of rural communities in the U.S. and Korea. He serves as a faculty facilitator for a collaborative international community development graduate program through the Great Plains Interactive Distance Education Alliance. E-mail: gary.goreham@ndsu.edu