Electing Women to the Japanese Lower House: The Impact of the Electoral System

Abstract

Researchers cite the Japanese electoral system as an influential determinant of women’s legislative representation. While there is a broad consensus in the literature that proportional-representational electoral systems create fewer obstacles to women’s representation, we are at a loss to explain how Japan’s mixed system affects the election of women to its Lower House. To the extent that this mixed system combines attributes of both single-member district (SMD) and proportionalrepresentation (PR) tiers, the impact of the mixed system on women’s representation is contingent on how the system works. The key to understanding this mechanism, we contend, lies in political parties’ nomination strategies. We therefore seek to understand whether and/or how the mechanisms of Japan’s electoral system operate to elect women. In this study, we highlight three components of a political party’s election strategy, 1) the allocation of candidates to different types of candidacy, 2) district assignments for SMD candidates, and 3) the placement of candidates on a PR election list. By analyzing six Lower House elections, which took place between 1996 and 2012, we find that the parties’ efforts to strategically coordinate these three components has an impact on the number of women elected to Japan’s Lower House. We also reveal that a high-ranking placement for a female candidate on a closed party list does not necessarily guarantee that she will win a PR seat, because the intertwined nature of the SMD and PR tiers makes outcomes in the SMD tier a prerequisite for winning in the PR tier.

Keywords:

women’s representation, Japan’s mixed system, party nomination strategy, SMD vs. PR systemsIntroduction

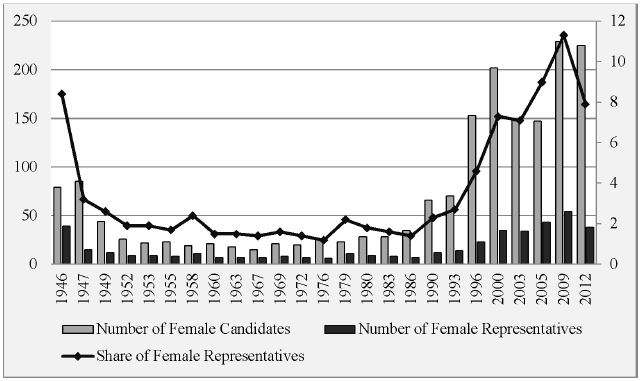

There is no question that Japanese women are underrepresented in various fields in society. According to the Gender Gap Index (GGI), Japan ranks 101st out of 145 countries. It is the paucity of women officials in the economic and political arenas in particular that has pushed Japan into the low rankings. Japanese women presently occupy only 9.5% of seats in the Lower House and 15.7% of those in the Upper House, giving Japan the rank of 155 out of 193 countries. While the number of women representatives has gradually increased, their percentage share in the Lower House has never surpassed 10% since the first women representatives were elected in 1946. The only exception to this pattern was the 2009 election, when 11.3% of seats were won by women. In the first election (1946), when a large constituency system was in place, 39 out of 79 women candidates gained a seat; this success rate represented a record high of 49.4%. Since then, however, the percentage share of women in the Lower House has hovered around two percent for nearly 50 years, under the now defunct multi-member district with a single non-transferable vote (MMD-SNTV) system (see Figure 1). When Japan adopted a mixed system in 1996, the number of women candidates and representatives increased.1

Women candidates and representatives of the Lower House, 1946-2012. Sourced from Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (2012) and Park (2007).

Current scholarship on the representation of women in the Japanese Lower House also shows that, under the Japanese mixed system, women have fared better in areas with proportional representation (PR) than in single-member district (SMD) systems (Eto, 2010; Ogai, 2001). After the introduction of the mixed system, the proportion of elected women in the Lower House increased from 2.7% in 1993 to 4.6% in 1996. This suggests that the introduction of the mixed system helped to elect women into office. Yet, it is important to note that the number of women elected to the Lower House has not increased in proportion to the number of women candidates, indicating low success rates.

While the underrepresentation of women occurs at every stage of the selection and election process, we primarily focus on the nomination and election of women. This study explores the extent to which the Japanese mixed system continues to have an impact on the number of women winning seats in either PR or SMD elections.

The Impact of Different Electoral Systems on Women’s Political Representation

Many scholars have noted the importance of electoral systems in shaping women’s political representation (Kenworthy & Malami 1999; Matland & Taylor, 1997; Norris, 1985; Rule, 1987, 1994; Sawer, 2010; Thames, 2016; Thames & Williams, 2013). It has been suggested that the type of system used partly determines women’s share of legislative seats. Existing studies have consistently shown that, among a host of electoral systems, party list PR systems provide women with better opportunities for election to office, enabling them to perform better than SMD systems do (Darcy, Welch, & Clark, 1994; Duverger, 1955; Kenworthy & Malami, 1999; Matland, 1998; Matland & Studlar, 1996; Norris, 1985; Rule, 1987, 1994).

In PR systems, political parties are generally more aware of the need to balance the ticket, so as to appeal broadly to voters across diverse social groups (Matland, 1998; Matland & Studlar, 1996; Norris, 2000, 2006; Rule, 1987; Vengroff, Creevey, & Krisch, 2000; Salmond, 2006). The logic behind this is as follows: since more than one representative is elected in multi-member districts under PR systems, parties tend to nominate several candidates. To maximize the number of seats a party gains in a district, it is strategically beneficial for that party to attract wider support from different constituencies. In this context, parties stand to gain more seats by nominating women candidates. They can also avoid intra-party conflicts between groups or party factions representing different interests (Norris, 2000).

In SMD systems, on the other hand, only one representative is elected in a district; parties must choose between the genders. As the costs of nominating a woman are likely to be higher, parties in this situation tend to select a male candidate (Matland, 1998). In short, PR systems provide parties with more incentives to nominate female candidates than SMD systems do, giving women more opportunities to run for office.

Corroborating these studies, more women have been elected in PR than in SMD areas under the Japanese mixed system during the previous six elections, between 1996 and 2012. Given the impact of the PR system, it is reasonable to assume that, in mixed systems, the positive effect of PR can, to some degree, compensate for the negative effect of the SMD system on electing women. However, Saito (2002) argues that it can be misleading to assume that simply introducing a PR system will automatically increase the number of women in the Lower House.

Although the two systems are often discussed as PR versus SMD, the impact of these electoral systems on the election of women does not create such a simple dichotomy. Despite the widely accepted benefits of PR systems for female candidates, recent studies have suggested that the relationship between the electoral system and the representation of women is rather complex: PR systems do not always bring more women into legislatures (McAllister & Studlar, 2002). In fact, some countries that use PR systems, such as Belgium and Israel, have fewer women parliamentarians than countries that do not, such as Canada and Australia (Iwanaga, 2008).

Alongside the established view that party list PR systems benefit women, some scholars have realized that an electoral system per se does not guarantee a particular level of representation (Norris, 2000). Others have suggested that the specific design of PR systems can influence the selection and election of women (Matland & Taylor, 1997; Vengroff et al., 2000). This is also true for mixed systems, which include some PR elements. In fact, the design of mixed systems may have a larger influence on the election of women because there are different types of mixed systems. For instance, PR lists can be open or closed; the two types of election outcomes (i.e., SMD and PR) can be linked or detached, and one type of outcome dominates the other. In other words, the general effects of mixed systems are contingent on how those systems operate. As Vengroff et al. (2000) have pointed out, “[m]ixed electoral systems allow us to do comparisons of these two [plurality (SMD) and PR] electoral system types within countries, thereby controlling for the impact of exogenous factors” (p. 218).

In the case of Japan, the SMD and PR systems should, in theory, operate independently. In reality, however, these two approaches are in some ways intertwined throughout the election process. More precisely, a candidate’s chance of obtaining a PR seat can be largely dependent on his or her performance in an SMD election. We still do not know whether this mechanism affects the election of women in the Japanese mixed system. The particular role played by this mechanism, we believe, lies in each party’s nomination strategy under SMD and PR rules.

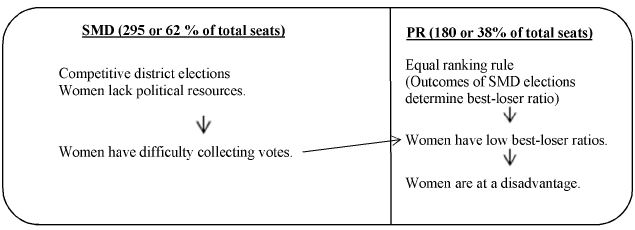

The Japanese Mixed System and Its Mechanism

In the Japanese mixed system, voters cast two ballots: One for an SMD candidate and the other for a political party in one of 11 regionally divided PR districts. Under this system, 295 candidates (about 62% of the total number of 475 members in the Lower House) are elected from SMD areas, and 180 (about 38% of the total number of 475 members in the Lower House) are chosen from PR blocs. Due to the higher proportion of SMD seats, the outcomes of SMD elections have a larger influence on the total outcome. This can create problems for women candidates, who tend to do better in PR elections.

The SMD elections are conducted using the first-past-the-post (FPTP) method of voting. Under this rule, an election has only one round, and the candidate who receives the most votes in a district is the sole winner of that district’s seat. To secure the only seat in a district, a candidate must ensure that all of his or her competitors lose (Salmond, 2006). These characteristics make SMD elections competitive and difficult to win. Furthermore, in SMD elections, where each voter in the district casts a ballot for a single candidate, an individual candidate’s ability to collect votes is a critical determinant of his or her chances of winning. Generally, candidates who have developed a strong support base in their districts (typically incumbents) have an advantage and access to resources needed to win an election—such as name recognition and a campaign fund—resources that female candidates rarely have (Martin, 2008).

Given the fact that SMD seats are highly competitive and difficult to win, Vengroff et al. (2000) have noted that “[t]he plurality [SMD] seats are considered to be more prestigious and highly prized, a factor that imposes an additional serious constraint for women” (p. 212). This creates a situation in which parties have an incentive to follow a vote-maximizing, risk-averse strategy by selecting men over women (Norris, 2006). For these reasons, it is unsurprising that parties nominate more male than female candidates for SMD elections.

By extension, male candidates may also have priority when it comes to district assignments. They are likely to be assigned preferred districts, such as a party or candidate’s stronghold, as discussed below. Since SMD systems create incentives for candidates to run on personal characteristics rather than a party label, candidates with the right personal characteristics can create stable voting coalitions that enable them to win seats on a regular basis. These coalitions are known as koenkai, or personal support organizations, in Japan. Women often find it difficult to mobilize the financial or patronage resources needed to run an effective campaign, particularly in candidate-centered systems. Thus, female candidates often find themselves at a disadvantage in such systems (Thames & Williams, 2010).

Under the general rules of PR systems, seats are allocated to each party in accordance with its share of the vote in each PR bloc. Some studies have shown that the formula used to allocate seats in PR systems can alter the election results. To calculate the distribution of seats among parties in each PR bloc, Japan’s PR system has adopted the d’Hondt method. Because of the way it distributes PR seats, this method is believed to slightly favor larger parties.2 Rule (1994) has suggested that the d’Hondt formula may be less supportive of women than a system that favors smaller parties (e.g., the Hare formula) because smaller parties are more likely to nominate female candidates. While PR systems generally favor smaller parties, the d’Hondt method may disadvantage female candidates in such parties.

Another PR feature that can affect the election of women is the type of list used to rank candidates: open or closed. Japan has a closed-list system in which candidates are ranked on the list in a pre-determined order. As a basic rule, each political party presents a list of candidates before an election; party winners are chosen from the top of the list. This distinction between open and closed lists is worth noting because election results can be changed, depending on who has more control (Golder et al., 2017; Luhiste, 2015; Thames & Williams, 2010).

In open-list systems, the candidates’ electoral fortunes may rest in the hands of voters, in the sense that voters are allowed to indicate their preferred party as well as their preferred candidates within the party (Golder et al., 2017; Reynolds, Reilly, & Ellis, 2005). In their EuroVotePlus experiment, Golder et al. (2017) demonstrate that, in more open systems (e.g., the open list system), when voters are given more freedom to choose their preferred candidates, their propensity to vote for women increases.

In closed-list systems, on the other hand, parties have more control over the electoral fortune of candidates. Since parties create the lists at their discretion, they are free to present a more diverse slate of candidates (Darcy, Welch, & Clark, 1994; Lakeman, 1976; Matland, 1998; Salmond, 2006): They can include candidates from minority groups who might otherwise have difficulty winning (Reynolds et al., 2005) or choose to list only those individuals most likely to secure a win. This suggests that closed-list systems give parties more freedom to place more (or fewer) women candidates near the top of their lists. As the cost of nominating female candidates is lower, they may wish to do so.

The Japanese mixed system has one distinctive rule that can alter candidates’ bids for PR seats. In fact, this structure is an important, albeit overlooked, factor that can affect the election of women to the Japanese Lower House. This rule allows parties to give dual candidates (running in both SMD and PR elections, as discussed below) the same ranking on their PR lists (Asahi Senkyo Taikan, 1997).

Two plausible benefits of this rule stand out. First, parties can reduce intra-party conflict over rankings (McKean & Scheiner, 2000). Deciding how to rank the candidates on PR lists can obviously be a challenge, especially for large parties with more candidates, because all of the candidates want to be given a higher ranking. Parties may also be criticized for placing women near the top of their lists. If a party gives all of its candidates an equally high rank, it can avert such conflicts among candidates within the party.

Second, by giving men and women the same rank, parties can, by extension, demonstrate to voters their fair treatment of candidates. After all, one important benefit of PR systems for women is the incentive they provide to political parties to appeal to different constituencies (Matland, 1998; Matland & Studlar, 1996; Norris, 2000, 2006; Rule, 1987; Vengroff et al., 2000). As Norris (2006) succinctly argues, “the exclusion of any major social sector, including women or minorities, could signal discrimination, and could therefore risk an electoral penalty at the ballot box” (p. 205). By giving women candidates the same high rank as their male counterparts on PR lists, parties can avoid this risk. Naturally, the equal ranking rule is convenient for parties, as it makes it much easier for them to create a balanced ticket.

The equal ranking rule appears to be a win-win strategy for both parties and candidates. However, it can still lower the chances of female candidates in PR elections, because the vote share in an SMD election is used to determine PR winners among equally ranked candidates; this is known in Japan as sekihairitsu, the best-loser ratio.3 A higher ratio will increase a candidate’s chance of winning a PR seat among equally ranked peers within the party. In other words, if women who struggle to win elections in the SMD system are equally ranked with men on PR lists, they remain disadvantaged in the PR elections.

Figure 2 summarizes the structure that underpins the representation of women within the Japanese mixed system. In the SMD section, female candidates with limited political resources have difficulty winning. In the PR section, women again face extra challenges when ranked equally with men, mainly because SMD outcomes are used to determine PR winners among equally ranked cohorts. In the end, given the larger proportion of SMD to PR seats (62:38), the SMD election outcomes are more weighted than PR outcomes, ultimately leading to the underrepresentation of women.

Given the structure of the Japanese mixed system and its effect on the representation of women, this study examines party nomination patterns, focusing on:

∙ The allocation of candidates to different types of candidacy;

∙ District assignments to SMD candidates; and

∙ Candidates’ placement on party lists in the PR system.

Once again, due to distinct SMD and PR election procedures, parties make decisions to endorse and coordinate candidates in a way that allows them to gain legislative seats. Nomination strategies for female candidates can differ from party to party, in turn determining how many women will ultimately be elected. This study investigates the three factors discussed above by observing five major parties: the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ), Komeito, the Japan Communist Party (JCP), and the Social Democratic Party of Japan (SDPJ).4

Allocation of Candidates

Parties have many choices to make when nominating candidates to SMD-only, PR-only, and dual candidacy. It is important to identify these three types of candidacy because their characteristics are determining factors for both parties and candidates, as they design their campaign and election strategies. Once a party endorses a candidate, it must decide whether that person will run in an SMD or PR election, or in both elections. During this decision process, parties consider various elements, including incumbency and seniority. The characteristics of each type of candidacy are briefly explained below, followed by an analysis of the nomination patterns of the five parties.

SMD-only candidates take part only in SMD elections. As previously discussed, SMD elections are difficult to win. On top of the competitive environment, SMD-only candidates who lose their bids have no chance of being saved in a PR election. Thus, this type of candidacy carries a higher risk of losing—even incumbents often fail to secure their seats. However, despite high levels of risk, some candidates intentionally run only in SMD elections, presumably to demonstrate their strength and decisiveness to voters. These candidates are generally big-name politicians; a certain number of candidates persistently run as SMD-only candidates (Kawato, 2013). There are only a few such politicians. Most candidates shy away from this type of candidacy, and most parties are reluctant to nominate candidates with a slim chance of winning for SMD elections alone.

PR-only candidates run only in PR elections; this too is a small group. Candidates who run only in PR elections are often placed either at the top or the bottom of the party list. Top rankings are reserved for special candidates, well-known, experienced politicians (e.g., former Prime Ministers), and people strongly supported by the party. This strategy is particularly evident among major parties that are sure to win at least one seat in a PR bloc. This position has some special advantages, in the sense that a candidate who is certain to win is not required to run the same sort of vigorous campaign as an SMD candidate. This special treatment benefits parties that want to include a big name on their PR lists and attract many votes. By contrast, bottom rankings can be filled with candidates who may not be serious about winning, included just to complete the PR list. Typically, these candidates are loyal party staffers or politicians’ administrative assistants (McKean & Scheiner, 2000). For the most part, candidates at the bottom of the list have almost no hope of winning.

Dual candidates run in an SMD race and, at the same time, are placed on the party’s corresponding PR list. One clear benefit of dual candidacy is that a candidate who loses an SMD election still has a chance of getting elected in the PR election. For any serious contender, dual candidacy may be a rational choice, as it raises the probability of winning a seat in one of two different elections. This is particularly true for candidates who do not have solid constituencies or strong support in their SMDs. It is possible for parties to give multiple candidates the same ranking on their PR lists (SMD- and PR-only candidates cannot be equally ranked). McKean and Scheiner’s (2000) study on the 1996 Lower House election found that few SMD losers were actually saved in the PR election. Examining Lower House elections between 1996 and 2012, Kawato (2013) argues that gaining a PR seat is not particularly easy for dual candidates who have lost SMD elections. His study finds that only one-third of dual candidates were successfully saved in the PR election after losing the SMD. While it offers dual candidates a second chance, the equal ranking rule also makes it more competitive for them to gain a PR seat.

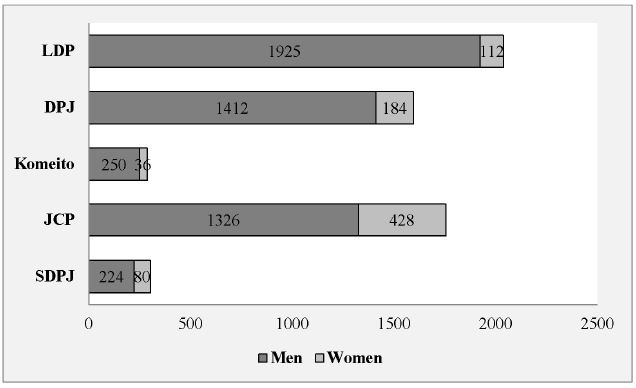

The Parties’ Patterns of Nominating Women Candidates

The five parties’ patterns of allocating candidates to the aforementioned three types of candidacy are one way to show how each party’s pattern affects the overall representation of women. All of the five parties examined overwhelmingly named more men than women, although some welcomed more women than others (see Figure 3).5 In all six elections, no parties except the SDPJ chose more than 30% female candidates.

Gender of candidates by party, 1996-2012. Candidates include all who ran in SMD and/or PR elections between 1996 and 2012. Sourced from Asahi Senkyo Taikan, the Asahi Shimbun, Asahi Shimbun Digital, and the Yomiuri Shimbun.

Of the five parties, the LDP appears to be the least supportive of women candidates, nominating only 5.5% women. In discussing the LDP and women candidates under the old MMD-SNTV system, Ogai (2001) has confirmed that the LDP was never a strong supporter of women. The LDP nominated more men than any other party, and its number of female nominees was disproportionally small. Yet the 2005 election was an exception. Although male candidates were still overwhelmingly dominant, the number of women candidates more than doubled. This leap was largely attributed to the former Prime Minister, Junichiro Koizumi’s, recruitment strategy. He centralized the nomination policy, one of various reforms carried out during his term of office (Reed, 2011).

As part of this strategy, Koizumi proactively nominated female candidates, who became known as Koizumi’s female children (Gaunder, 2012). His recruitment strategy was particularly meaningful, given the fact that the LDP had never been a strong supporter of female candidates. However, the impact of Koizumi turned out to be short-lived, due to his departure from politics and the declining popularity of the LDP by the 2009 election. In two subsequent elections, we have witnessed little change in the number of female candidates; however, the success rates of LDP female candidates have been relatively high (69.6%) throughout all six elections. These high success rates can be explained by the fact that a relatively high percentage of LDP women candidates are incumbents.

The DPJ seems reasonably supportive of female candidates, with a substantial number of nominated women. It has 184 female candidates in total, the second largest group after the JCP. Its recruitment practices and strategies appear to have worked well. The DPJ was the first party to launch the Water and Seeds Program (more colloquially known as the open recruitment program), which provides women candidates with financial support (Gaunder, 2012). While this program does not focus solely on female recruitment (Gaunder, 2012), it offers opportunities to women who might otherwise find it difficult to launch their political careers.

A remarkable increase in the number of women candidates in 2009 can be attributed to Ichiro Ozawa’s recruitment strategy. Ozawa, recognized as the DPJ election mastermind, mostly handpicked female candidates (Dickie, 2009). They were called the Ozawa girls, and some were strategically selected to run against senior male veterans of the LDP and Komeito in SMD races (Gaunder, 2012). In fact, Ozawa’s strategy of actively nominating women was similar to that of the LDP’s Koizumi. Ozawa’s strategy helped to nearly double the number of female candidates in the 2009 election: 46 women stood for office; of these, 40 won a seat. It was the largest number of female representatives ever sent to the Lower House by any party.

Naturally, the DPJ women’s major victory helped to increase overall female representation in 2009: the number of women legislators rose to 54, and the percentage of women in the Lower House reached double digits (11.3%) for the first time since Japanese women gained the right to vote and run for office in 1945. Despite this achievement, fewer DPJ women ran for office in the 2012 election, following Ozawa’s departure from the party. Nevertheless, the party has maintained the second largest number of female candidates after the JCP.

Parties on the left, particularly those with a centralized process of candidate selection, have been more likely to nominate women (Stevens, 2007; Studlar & McAllister, 1991). The socialist and leftist SDPJ and JCP have nominated more women than other parties. On average, one out of every four candidates was female for both parties in the six elections. Indeed, the SDPJ and JCP have a long history of supporting women candidates since the MMD-SNTV system was first introduced. The SDPJ made a significant contribution to encouraging more women to run for office, and “half of all of the party’s national officeholders were women” (Martin, 2013, p. 175). In fact, the JSP (predecessor of the SDPJ) was the center of the “Madonna Boom” under the MMD-SNTV system (Iwai, 1993). However, the number of women candidates and election winners has steadily decreased since the 2000 election. In 2012, no SDPJ women were elected.

The aforementioned three parties—the LDP, DPJ, and SDPJ—tend to nominate women as dual candidates. In assessing the use of dual candidacy, Martin (2013) explains “how important it is that large parties run more women candidates for both SMD and PR seats” (p. 172). While dual candidacy gives candidates a chance to be selected in the PR election if they lose in the SMD election, PR elections do not save many candidates, as Kawato (2013) has pointed out. For instance, despite the relatively large number of DPJ women put forward, their success rates were only 40.2% in the six elections. This can be explained in part by the DPJ’s frequent use of equal ranking on its PR lists.

The JCP always nominates more women than any of the other parties. The total number of women in all six elections comes to 428, which is more than half the number of female candidates of all five parties combined. To run is one thing, to win is another. Although the JCP has contributed to an increase in the number of women candidates overall, their success rates are exceptionally low, with no more than five winners in each election. Again, the party’s nomination strategy is mainly responsible for this. Unlike the other four parties, a majority of JCP nominees ran only in SMD elections. Almost all (98%) of female SMD-only candidates were affiliated with the JCP. Given how difficult it is to win an SMD election, the JCP’s nomination pattern is something of a puzzle.

Furthermore, while the big-name politicians of other parties often run only in SMD races, this is not necessarily the case for the JCP. Despite its considerable number of SMD-only candidates, none of them won an SMD seat in all six elections. Although the JCP’s efforts may seem ill-fated, this nomination strategy is actually based on JCP policy. Place a candidate in every single district (except in Okinawa) in order to provide voters with an alternative (Japan Communist Party, 2014). We predict that, unless the JCP changes its nomination strategy, women candidates will have little chance of being elected.

Komeito presents a different nomination pattern from the other parties: all of its female candidates ran in PR-only elections, except for one, who ran as dual candidate in the 2000 election. For Komeito, focusing on PR-only candidates seems a practical choice. Since its primary support base is the religious organization, Soka Gakkai, Komeito candidates mainly rely on support from organization members. This, of course, works well in the closed-list PR system, where voters cast a ballot for a party.

Another explanation of Komeito’s preference for PR-only candidates is its status as a junior coalition partner of the LDP since the late 1990s (Aoki, 2014). Reportedly, the LDP and Komeito have established some strategic coordination to avoid direct competition in elections. While Komeito has nominated very few women (only 36 women in all six elections), their success rates have been high: two-thirds or more of the party’s female candidates have won their seats in every election except 2000. An empirical finding on these high success rates has also been reported by Martin (2013), “when Komeito runs women candidates, they have a high chance of winning” (p. 173).

Clearly, the gender composition of candidates varies from party to party. The leftist JCP and socialist SDPJ have nominated more women than the other parties. Corroborating the findings of previous studies, Japan’s leftist parties are also more likely to support women. Their gender composition indicates their level of support for women candidates. However, as has been noted, nominating more women has not necessarily guaranteed electoral success. Each party’s nomination pattern appears to be an important determinant (if not the most important) of election outcomes. Consider the JCP. While the JCP has nominated more women than any other party, a majority have run only in SMD elections, where women have more difficulty winning than men. The following section examines how district assignments and competition between candidates in SMD elections affect outcomes with a particular focus on district-specific factors.

District Assignment and Competition in SMD Elections

For SMD elections, a candidate’s ability to collect votes is a crucial factor, affecting the party’s nomination strategy. In addition to the candidate’s ability, the characteristics of his or her district may also determine the election outcomes of the SMD race. To explain the underrepresentation of Canadian women in politics, Thomas and Bodet (2013) have argued that women candidates—even incumbents—tend to be nominated in unwinnable districts where they have a slim chance of winning. In other words, women are more likely to be sacrificial lambs in a district race. In another study, Matland and Studlar (1996) focused on an incumbent to measure the competitiveness of a race.

As these studies clearly indicate, SMD elections are influenced, not only by who runs, but also by where they run. Following the literature, this study examines two factors, mainly to determine district assignments and the competitiveness of particular districts. The two factors are as follows: running for open seats and running in a landslide or nearly tied election, the latter being a determining factor for dual candidacy in the PR system. In the Japanese mixed system, the competitiveness of SMD elections is significant because it determines a win (or a loss) not only in SMD but also in PR elections, among equally ranked candidates on the lists.

Running for Open Seats

The existing literature suggests that running as an incumbent, regardless of gender, gives candidates a substantial advantage in elections. Incumbents with political experience have an advantage when running for office (Schwindt-Bayer, 2005; Studlar & McAllister, 1991). As a result, it is more difficult for challengers to win the election (Herrnson, Lay, & Stokes, 2003). In the case of Japan, personal support organizations, or koenkai, bring an added value to politics (Curtis, 1971). Without koenkai, it is difficult for candidates to finance or carry out their campaigns, or even to make personal contacts (Christensen, 2000). Without doubt, the koenkai are a valuable political resource. Incumbents have a distinct advantage because they have developed voter loyalty in their districts over a period of time through their koenkai. When it comes to political capital, female candidates are disadvantaged in the Japanese context, in comparison to their male counterparts, due to the shortage of koenkai (Martin, 2008). In general, incumbents perform better; however, few Japanese women enjoy the incumbency advantage.

Table 1 illustrates the three types of district assignments open to SMD contenders by gender (i.e., SMD-only and dual candidates) for all five parties from 1996 to 2012. These are as follows: 1) the candidate ran as an incumbent, 2) the candidate ran as a challenger, and 3) no incumbent ran (an open seat). Noticeably, most women ran as challengers: 80% of female candidates, in comparison to slightly more than half of their male counterparts. Conversely, there were fewer women incumbents: the proportion of women incumbents was about 25 percentage points less than men. The large number of male incumbents seems to have left few open seats. Among both men and women, few candidates ran in open-seat districts.

Table 1 illustrates candidates’ performance in SMD elections using success rates.6 In the case of male candidates, more than two-thirds of incumbents (67.4%) were successfully re-elected, as expected. Female incumbents, on the other hand, had a hard time retaining their seats: only 42.4% were successful. This figure suggests that men enjoy more of an incumbency advantage than women. Fewer women are incumbents to begin with, and female incumbents seem less competitive than their male counterparts.

As challengers, men once again had higher success rates (16.7%) thanwomen (7.9%). The success rates of open-seat candidates reveal an evenlarger difference between men and women. In open-seat districts, onemight expect female candidates to have a better chance of gaining a seatthan in the other two types of districts. Contrary to expectations, however, only one female candidate managed to fill a seat, resulting in a four percentsuccess rate. It is true that few open seats were available, yet, seemingly, male candidates were more likely to fill those seats.

Running in a Landslide or Nearly tied Election

The second aspect of district competitions involves the way in which SMD elections end, whether in a landslide or a near-tie. Examining this aspect provides insights, not only into the impact of district competitions on SMD election outcomes, but also into those of PR elections via best-loser ratios for dual candidates, as the latter are determined by the candidates’ performance in SMD elections. For the sake of simplicity, we present two possible scenarios that can affect winning and the share of votes.

The first scenario is a landslide election, where one candidate collects the most votes. If candidate A wins the most votes in his or her district, and candidate B is assigned to run in the same district, then candidate B will end up collecting a smaller number of votes. For the purposes of this discussion, a landslide election is defined as a more than 50% difference in the number of the votes received by the SMD winner (candidate A) and the 2nd place finisher (candidate B)—for example, where candidate A gained 50,000 votes and candidate B gained 24,000 votes). In this case, there are few votes left for other candidates. If a contender like candidate A runs in the same district, it will be difficult for others not only to win the race, but also to gain more votes.

Thus, candidates who finish below 2nd place are likely to receive a very small number of votes. This is particularly important for dual candidates, because the votes they gather may be factored in later (as their best-loser ratios) to determine PR winners. In accordance with the definition of a best-loser ratio, SMD losers in a landslide election are likely to receive low ratios, thus making it unlikely that they will secure a PR seat. In a nutshell, it is difficult for candidates to win in a landslide-SMD election. Even worse, it may also lower their chances of gaining a PR seat.

The second scenario unfolds when a race ends in a near-tie between the top two candidates. A nearly tied election is when the SMD winner (candidate A) receives less than 10% more votes than the 2nd place finisher (candidate B)—for example, when candidate A gains 50,000 votes and candidate B 48,000 votes). In such an election, the top two candidates both have a chance to win. However, those who finish 3rd or below will have no chance of winning. Furthermore, if these losers are dual candidates, only the 2nd place finisher (the top loser) will enjoy a high best-loser ratio, making it highly likely that he or she will win a place in the PR race. The best-loser ratios of the other contenders will be very low, decreasing their chances of winning in the PR election.

Approximately the same number of SMDs end in landslides (315 or 17.5%) as in nearly tied elections (326 or 18.1%). Of the five parties, more candidates of both genders ran in landslides than in nearly tied elections. Table 2 reports both types of election outcome by gender; two conclusions stand out. First, the share of women running in landslide elections is about seven percentage points higher than the percentage of women running in very close elections, whereas the difference for men is about three percentage points. In other words, female candidates are more likely to run in landslide elections. Running in a landslide election may reduce their chances of gaining seats in the SMD election.

Second, examining SMD losers who finished in 2nd place and below, we note that more women have lost in landslides than in nearly tied elections. As a consequence, the proportion of female winners in landslide elections (13.3%) was smaller than the proportion who ran in nearly tied elections (20.5%). This higher percentage of women who win nearly tied elections suggests that women are competitive when elections are very close. This is especially noticeable in three parties—the DPJ, JCP, and SDPJ. Male candidates also ran more often in landslide elections (18.4%) than nearly tied elections (15.9%). However, the percentage of winners in landslide elections (18.9%) was higher than that in nearly tied elections (16.9%). This indicates that, when men and women run in the same district, the winner tends to be a man. Women usually finish 2nd or below. Incumbents are no exception. More than half of female incumbents failed to retain their seats in landslide elections, as did one-third of female incumbents in nearly tied elections.

A closer examination of SMD district assignments and competitions suggests that women candidates are more likely to challenge incumbents. In addition, women tend to run in landslide elections where even incumbents struggle to get re-elected. More importantly, losing by a landslide can be a blow to dual candidates who are equally ranked. Since the vote ratio of an SMD loser vis-à-vis the winner (i.e., the best-loser ratio) is a determinant of winning in the PR election, losing by a large margin lowers a candidate’s chances of being saved in the PR election. On the other hand, an SMD loser who is nearly tied with the winner—typically, a 2nd place finisher in a very close election—may have a better chance of getting elected in the PR election, given his or her larger best-loser ratio.

Equally ranked candidates may attempt to end as close as possible to the winner in order to obtain higher best-loser ratios than other candidates. Note that PR lists include dual candidates running in different SMD elections; this means that, once PR seats have been allocated to each party by vote share, gaining a PR seat becomes an intra-party competition. Thus, equally ranked candidates need to do better in comparison to equally highly ranked competitors within the party. It is therefore possible for a loser who performed well (in a nearly tied SMD race) to end up with a lower-best loser ratio than competitors of equal rank within the party, if the latter do better in their SMD elections, thus acquiring higher best-loser ratios.

Sometimes, candidates with very high best-loser ratios, say 98%, end up failing to win a PR election because candidates from other SMD elections obtain even higher ratios, say 99%. For equally ranked SMD losers, this aspect of the PR list makes it more difficult to win a PR seat, a situation that is even worse for women candidates. Since women candidates do not fare well in SMDs, compared to their male counterparts, the best-loser ratios of women tend to be lower than those of men. On top of that, nearly half of women candidates who compete in PR races are equally ranked, allowing the performance of equally ranked candidates to influence the overall number of elected women.

The Placement of Candidates on PR Lists

The placement of female candidates on PR lists is another way to assess party nomination patterns and the representation of women. As Haavio-Mannila et al. (1985) have argued, “the ranking of the candidates on the list is of vital importance to their chances of election. Attention must be turned, therefore, not only to entering women on the lists, but placing them in eligible positions” (italics in original) (p. 56). To examine the ranking of women candidates, the authors classified the list positions into three groups: mandate; fighting; and ornamental places. Mandate places represent positions in which a candidate almost always secures his or her seat. Conversely, ornamental places are basically for show, where a candidate has a minimal chance of winning. Fighting places lie between mandate and ornamental places. In this position, the electoral success of a candidate is contingent on the number of seats a party gains, which can change from election to election. Studies found fewer women in mandate positions and more women in ornamental ones in the Nordic countries (Haavio-Mannila et al., 1985) and Costa Rica (Matland & Taylor, 1997).

In general, list positions are based on the candidates’ prospects of winning. In the case of the Japanese PR system, however, there are additional options, due to the equal ranking rule: candidates can be individually or equally ranked. How they are ranked on the list is critical in the sense that it affects their chances of winning in the PR election.

For individually ranked candidates, the factor that determines whether they gain PR seats is their ranking on the list. Candidates who obtain the top positions on the lists have a good chance of being elected; therefore, they are placed in mandate positions. This is not the case for candidates who are equally ranked, because even if they are placed near the top of the list, their wins are not guaranteed. Their prospects of winning may depend on others, e.g. how well they competed in the SMD elections (i.e., their best-loser ratios), thus placing them in fighting rather than in mandate places.

As previously discussed, parties have an incentive to balance their tickets between men and women. The equal ranking rule makes it easier to do so. For this reason, parties might be encouraged to offer fighting positions to both men and women, leading us to assume that there is no gender difference in the fighting positions. By extension, we might further assume that there will be no overrepresentation of women in ornamental positions, in contrast to previous studies. Why not? Parties that place women disproportionately in ornamental positions risk being punished at the ballot box for their unfair treatment of women candidates. Logically, the equal ranking rule makes sense to parties.

Table 3 illustrates the placement of candidates on PR lists by gender and party. As expected, most candidates are placed in the fighting positions. This is apparent for parties that often place candidates equally on their lists, such as the LDP, DPJ, and SDPJ. By ranking women and men equally in the fighting positions, parties may have little incentive or need to place women in ornamental positions. In fact, women candidates are not necessarily overrepresented in these parties’ ornamental positions.

In the cases of Komeito and the JCP, which tend to rank candidates individually, more women are placed in ornamental places and more men are given mandate positions. The larger share of candidates in fighting positions and scarcity of mandate slots mean that the success rates of candidates in the fighting positions will affect the election outcomes and the number of women represented in the PR election.

For those who are equally ranked on the lists, including most candidates in fighting positions, a higher ranking is necessary but not sufficient to be successful in the PR. This is largely because wins are often determined by best-loser ratios, leading us to further examine these ratios. We know now that the best-loser ratios of female candidates are lower than those of their male counterparts, mainly due to the women’s unsuccessful bids in earlier SMD elections. Consequently, women’s poor performance in the SMD gains them low best-lower ratios, ultimately reducing their chances of gaining a seat in the PR election.

Table 4 demonstrates the median best-loser ratios of equally ranked candidates by party and gender.7 For the sake of precision, we have categorized dual candidates by whether their best-loser ratios can be used to determine PR wins (see footnote for more detailed sorting process criteria).8 Looking at the total number, one can see that women have gained 52.2%. This suggests that these candidates lost an SMD election by a large margin, gaining, on average, little more than half the votes won by the district winner. At the same time, the best-loser ratios of their male counterparts are, on average, 66.7%, about 15 percentage points higher. This clear difference in best-loser ratios indicates that the men have a higher probability of being successful in the PR election.

Examining the ratios by party, Table 4 shows variations in the average best-loser ratios, as well as a gender difference in party ratios. LDP and DPJ women gained lower ratios than men; DPJ women, in particular, were eight percentage points lower than their male counterparts. This suggests that fewer PR seats are won by women candidates. By contrast, SDPJ women had ratios about seven percentage points higher than their male counterparts, suggesting that these women are more likely to win PR seat than the men in their party.

The conclusion revealed by this data is clear. Because equally ranked candidates are compelled to compete with other candidates within the party, and the best-loser ratios determine their chances of winning a PR election, the overall lower best-loser ratios of women suggest that they have less chance of winning PR seats than men. In fact, the success rates of equally ranked male and female candidates differ across all five parties. Across all parties, men are more successful (26%) than women (20.6%). By party, LDP and DPJ women had lower success rates—about 6 and 10 percentage points lower, respectively—than their male counterparts.

Only SDPJ women attained higher best-loser ratios and higher success rates—about 17 percentage points higher—than their male counterparts. Yet the SDPJ women’s higher success rates do not contribute much to the overall number of elected women in the Lower House, since the SDPJ tends to win a small number of seats in each PR bloc—on average one to three seats or sometimes no seat in some blocs. On the other hand, while the LDP and DPJ tend to win more PR seats in all PR blocs, the winning seats are likely to go to male candidates, with their high best-loser ratios.

Conclusions

The underrepresentation of women in the political arena is still a salient issue in most countries, although women in some countries occupy more than or nearly half of the legislative seats in parliaments. Scholars have offered various explanations for this phenomenon from an institutional perspective ever since Duverger’s (1954) seminal work on the effects and consequences of electoral systems. While there is a general agreement on the institutional features that favor women, we also know that political systems and rules vary from country to country, requiring different explanations. Mixed systems are a relatively minor variant of election systems worldwide: only 46 (17%) out of 270 countries uses this system (the Inter-Parliamentary Union). Ever since more countries adopted this system over the past decades, a growing number of scholars have examined it in a more systematic and empirical way.

In the case of Japan, which joined the family of mixed systems in 1994, there are still very few empirical studies on the connections between women’s representation and the mixed system. One reason may be the complexity of the system. Yet, as Vengroff et al. (2000) have suggest, mixed systems are useful for examining two different electoral systems (usually SMD and PR) within a country. Mixed systems also allow us to analyze how the operation of the combined system affects political phenomena.

We have focused on the impact of the Japanese mixed system on the election of women to the Lower House, with political parties as key players. The introduction of the mixed system provided political parties with a wide range of choices: allocating candidates to different types of candidacy, assigning districts for SMD elections, and placing candidates on PR lists. These choices demonstrate different patterns from party to party, mirroring each party’s strategy; they have resulted in fewer elected women in the Lower House. Overall, the data analysis suggests that there are three main reasons for women’s lack of success in SMD elections. First, the low success rates of women candidates can be mainly attributed to the large number of SMD-only candidates. The JCP, which has the largest number of women candidates, follows a puzzling policy of SMD-only candidacy. Second, although there are few women incumbents, many of these are unsuccessful in SMD re-elections. Third, women candidates are likely to run as challengers and in landslide elections, which makes it more difficult for them to win. In the Japanese mixed system, women’s low success rates in SMD elections are channeled into the outcomes of PR elections. This is especially detrimental to equally ranked dual female candidates, since they tend to gain lower ratios than their male counterparts; these ratios are determined by the candidates’ vote share in the SMD. This linkage between the election outcomes of the SMD and PR elections reduces a positive effect of the PR on women.

One reason why PR systems favor women candidates involves the incentive for parties to balance their tickets on the candidate lists, in order to gain more support. For this reason, parties may place women reasonably high on their lists. Japan’s equal ranking rule allows parties to conveniently achieve their purpose by naming both men and women of a high ranking. However, reality tells a different story. It is true that, due to this equal rating rule, women candidates can be ranked as high as their male counterparts. However, women’s lower best-loser ratios reduce their chances of winning in the PR election. Unfortunately, recent trends reveal that larger parties are leaning toward placing candidates (both men and women) equally in almost all PR blocs. Once again, while the equal ranking rule may appear to be fair to both men and women, it is unlikely to achieve a fair result until more women have been nominated and elected in the SMD elections. Therefore, in the case of Japan, the PR system will prove to be more beneficial to women when they are individually ranked high on the lists.

Notes

References

- Aoki, M., (2014, November, 20), Komeito’s 50 years of losing its religion, The Japan Times, Retrieved January 30, 2016, from http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2014/11/20/national/politics-diplomacy/komeitos-50-years-of-losing-its-religion/#.V4-d_spTHIW (In Japanese).

- Asahi Senkyo Taikan, (1997), Asahi overview of elections: The 41st house of representatives general election, the 17th house of councillors ordinary election, postwar election results of house of representatives and councilors, Tokyo, Japan, Asahi Shimbunsha, (In Japanese).

- Asahi Shimbun Digital, (2005), Election results, Retrieved March 20, 2014, from http://www.asahi.com/senkyo2005/ (In Japanese).

- Asahi Shimbun Digital, (2009), Election results, Retrieved March 20, 2014, from http://www.asahi.com/senkyo2009/ (In Japanese).

- Asahi Shimbun Digital, (2012), Election results, Retrieved March 20, 2014, from http://www.asahi.com/senkyo/sousenkyo46/ (In Japanese).

- Christensen, R., (2000), The impact of electoral rules in Japan, In R. J. Lee, & C. Clark (Eds.), Democracy and the status of women in East Asia, p25-46, Boulder, CO, Lynne Rienner.

- Curtis, G. L., (1971), Election campaigning Japanese style, New York, NY, Columbia University Press.

- Darcy, R., Welch, S., & Clark, J., (1994), Women, elections and representation, Lincoln, NB, University of Nebraska Press.

- Dickie, M., (2009, October, 7), Vibrant ‘Ozawa Girls’ to refresh diet, The financial times Asia-Pacific, Retrieved January 30, 2016, from http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/96384eb8-b364-11de-ae8d-00144feab49a.html#axzz2lmJlz7ja.

- Duverger, M., (1954), Political parties, New York, NY, Wiley.

- Duverger, M., (1955), The political role of women, Paris, The United Nations Economic and Social Council.

- Election results, (2000, June, 26), Asahi Shimbun, p4-10, (In Japanese).

- Election results, (2003, November, 10), Yomiuri Shimbun, p4-6, (In Japanese).

- Eto, M., (2010), Women and representation in Japan: The causes of political inequality, International Feminist Journal of Politics, 12(2), p177-201.

-

Gaunder, A., (2012), The DPJ and women: The limited impact of the 2009 alternation of power on policy and governance, Journal of East Asian Studies, 12, p441-466.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/s1598240800008092]

-

Golder, S. N., Stephenson, L. B., der Straeten, K., Blais, A., Bol, D., Harfst, P., & Laslier, J-F., (2017), Votes for Women: Electoral Systems and Support for Female Candidates, Politics & Gender, 13, p107-131.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/s1743923x16000684]

- Haavio-Mannila, E., & Skard, T. (Eds.), (1985), Unfinished democracy: Women in Nordic politics, New York, NY, Pergamon.

-

Herrnson, P. S., Lay, J. C., & Stokes, A. K., (2003), Women running “as women”: Candidate gender, campaign issues, and voter-targeting strategies, Journal of Politics, 65(1), p244-255.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2508.t01-1-00013]

- Inter-Parliamentary Union, (2016), Parliaments at a glance: Electoral systems, Retrieved January 27, 2016, from http://www.ipu.org.

- Iwai, T., (1993), “The Madonna Boom”: Women in the Japanese diet, Journal of Japanese Studies, 19(1), p103-120.

- Iwanaga, K., (2008), Women’s political representation in Japan, In K. Iwanaga (Ed.), Women’s political participation and representation in Asia: Obstacles and challenges, p101-129, Copenhagen, Denmark, NIAS Press.

- Japan Communist Party, (2014, November, 27), Questions about the LDP’s manifesto, JCP’s nomination policy, JCP’s policy for the sources of government revenue, and so on: Shii clearly answers these questions, Retrieved January 30, 2016, from http://www.jcp.or.jp/akahata/aik14/2014-11-27/2014112701_04_1.html (In Japanese).

- Kawato, S., (2013), Party competitions under the mixed system, Quarterly Jurist, p75-85, (In Japanese).

-

Kenworthy, L., & Malami, M., (1999), Gender inequality in political representation: A worldwide comparative analysis, Social Forces, 78(1), p235-268.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/78.1.235]

- Lakeman, E., (1976), Electoral systems and women in parliament, Parliamentarian, 57, p159-162.

-

Luhiste, M., (2015), Party gatekeepers’ support for viable female candidacy in PR-list systems, Politics & Gender, 11, p89-116.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/s1743923x14000580]

- Martin, S. L., (2008), Keeping women in their place: Penetrating male-dominated urban and rural assemblies, In S. L. Martin, & G. Steel (Eds.), Democratic reform in Japan: Assessing the impact, p125-149, Boulder, CO, Lynne Rienner.

- Martin, S. L., (2013), Women candidates and political parties in election 2012, In R. Pekkanen, S. R. Reed &, E. Scheiner (Eds.), The Japanese general election, p170-176, New York, NY, Palgrave Macmillan.

- Matland, R. E., (1998), Women’s representation in national legislatures: Developed and developing countries, Legislative Studies Quarterly, 23(1), p109-125.

-

Matland, R. E., & Studlar, D. T., (1996), The contagion of women candidates in single-member district and proportional representation electoral systems: Canada and Norway, The Journal of Politics, 58(3), p707-733.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/2960439]

- Matland, R. E., & Taylor, M. M., (1997), Electoral system effects on women’s representation: Theoretical arguments and evidence from Costa Rica, Comparative Political Studies, 30(2), p186-210.

-

McAllister, I., & Studlar, D. T., (2002), Electoral systems and women’s representation: A long-term perspective, Representation, 39(1), p3-14.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00344890208523209]

- McKean, M., & Scheiner, E., (2000), Japan’s new electoral system: La plus ça change, Electoral Studies, 19(4), p447-477.

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, (2012), Election Data, Retrieved August 12, 2015, from http://www.soumu.go.jp (In Japanese).

-

Norris, P., (1985), Women’s legislative participation in Western Europe, West European Politics, 8(4), p90-101.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/01402388508424556]

- Norris, P., (2000), Women’s representation and electoral systems, In R. Rose (Ed.), Encyclopedia of electoral systems, p1-10, Washington, DC, CQ Press.

-

Norris, P., (2006), The impact of electoral reform on women’s representation, Acta Politica, 41, p197-213.

[https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500151]

-

Ogai, T., (2001), Japanese women and political institutions: Why are women politically underrepresented?, Political Science and Politics, 34(2), p207-210.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/s1049096501000312]

- Park, I., (2007), Political recruitment of women of the house of representatives, Journal of the National Women’s Education Center of Japan, 11, p95-102, (In Japanese).

- Reed, S. R., (2011), The evolution of the LDP’s electoral strategy: Towards a more coherent political party, In L. J. Schoppa (Ed.), The Evolution of Japan’s party system: Politics and policy in an era of institutional change, p43-62, Toronto, Canada, University of Toronto Press.

- Reynolds, A., Reilly, B., & Ellis, A. (Eds.), (2005), Electoral system design: The new international IDEA handbook, Stockholm, Sweden, International IDEA.

-

Rule, W., (1987), Electoral systems, contextual factors, and women’s opportunity for election to parliament in twenty-three democracies, Western Political Quarterly, 40(3), p477-498.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/106591298704000307]

- Rule, W., (1994), Parliaments of, by and for the people: Except for women?, In W. Rule, & J. F. Zimmerman (Eds.), Electoral systems in comparative perspective: Their impact on women and minorities, p15-30, Westport, CT, Greenwood Press.

- Saito, H., (2002), Reasons for a small number of female representatives and its increase, Sophia University Junior College Division Faculty Bulletin, 22, p61-84, (In Japanese).

-

Salmond, R., (2006), Proportional representation and female parliamentarians, Legislative Studies Quarterly, 31(2), p175-204.

[https://doi.org/10.3162/036298006x201779]

- Sawer, M., (2010), Women and elections, In L. Lawrence, R. G. Niemi, & P. Norris (Eds.), Comparing democracies 3, p202-222, Los Angeles, Sage.

-

Salmond, R., (2006), Proportional representation and female parliamentarians, Legislative Studies Quarterly, 31, p175-204.

[https://doi.org/10.3162/036298006x201779]

-

Schwindt-Bayer, L. A., (2005), The incumbency disadvantage and women’s election to legislative office, Electoral Studies, 24(2), p227-244.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2004.05.001]

-

Smith, D. M., (2013), Candidate recruitment for the 2012 election: New parties, new methods…same old pool of candidates?, In R. Pekkanen, S. R. Reed, & E. Scheiner (Eds.), Japan decides 2012: The Japanese general election, p101-122, New York, NY, Palgrave Macmillan.

[https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137346124_9]

- Stevens, A., (2007), Women, power and politics, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan.

-

Studlar, D. T., & McAllister, I., (1991), Political recruitment to the Australian legislature: Toward an explanation of women’s electoral disadvantages, The Western Political Quarterly, 44(2), p467-485.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/448790]

- Thames, F. C., (2016), Understanding the impact of electoral systems on women’s representation, Politics and Gender, p1-26.

-

Thames, F. C., & Williams, M. S., (2010), Incentives for personal votes and women’s representation in legislatures, Comparative Political Studies, 43(12), p1575-1600.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414010374017]

- Thames, F. C., & Williams, M. S., (2013), Contagious representation: Women’s political representation in democracies around the world, New York, NY, New York University Press.

-

Thomas, M., & Bodet, M. A., (2013), Sacrificial lambs, women candidates, and district competitiveness in Canada, Electoral Studies, 32(1), p153-166.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2012.12.001]

-

Vengroff, R., Creevey, L., & Krisch, H., (2000), Electoral system effects on gender representation: The case of mixed systems, Japanese Journal of Political Science, 1(2), p197-227.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/s1468109900002024]

Biographical Note: Miyuki Kubo is a Ph.D. student at Texas Tech University. Her interests include gender and politics, Japanese politics, and Asian politics. E-mail:miyuki.kubo@ttu.edu

Biographical Note: Aie-Rie Lee is Professor of Political Science at Texas Tech University. She received her Ph.D. from Florida State University and joined Texas Tech in 1989. Her areas of specialization include comparative political behavior with an emphasis on East Asia, political development, democratization, and gender politics. Her work has appeared in such journals as Comparative Political Studies, Social Science Quarterly, International Journal of Public Opinion Research et al. E-mail: aierielee@gmail.com