Gender Attitudes among “Involuntary” Bachelors and Married Men in Disadvantaged and High Sex Ratio Settings: A Study in Rural Shaanxi, China

Abstract

Compared to class relations, gender relations in high sex ratio contexts are understudied. Drawing on data from a survey conducted in rural southern Shaanxi, China, in 2014–2015, this article aims to assess if the section of the never-married male population who wishes to marry but face difficulties in achieving this goal is more or less gender equal in their attitudes than married men and, if so, in what aspects. Results provide further evidence that the role of the husband as the main economic support of the family and that of the wife, centered on the domestic sphere, remain firmly rooted in attitudes. However, the same results indicate that men who are squeezed out of marriage are not only the least endowed in socioeconomic capital but are also more likely than married men to confine women to their roles as wives and mothers; the “involuntary” bachelors report more conservative gender attitudes than their married counterparts mainly because they are less educated, more conservative with respect to other norms, and not exposed to marital life. All things being equal, marriage tends to make men more gender equal. In parallel, the involuntary bachelors make more demands on women’s economic contribution to the household; this sheds light on the stratifying effect of marriage as the marriage-squeezed men seek to escape poverty through marriage.

Keywords:

rural China, sex ratios, bachelorhood, gender attitudes, gender rolesIntroduction

The literature investigating women’s and men’s partnership behavior in contexts where men significantly outnumber women in the adult population applies the demographic-opportunity thesis, either directly or indirectly, to establish that such an imbalance affects men’s marriage prospects by creating a male marriage squeeze, given that more men than women are potentially looking for a partner of the opposite sex (Eklund & Attané, 2017; Guttentag & Secord, 1983). Thus, men would face increased competition with their peers to meet women for a long-term partnership, as shown for China where marriage remains the socially dominant model (Ji & Yeung, 2014; Yu & Xie, 2015). Yet, this has implications for class relations: as Chinese women have more choice in terms of mate selection, they tend to practice social hypergamy to advance their class position by marrying a man of a higher socioeconomic status (Du, Wang, & Zhang, 2015; Mu & Xie, 2014). As a consequence, opportunities to meet potential spouses are limited, mainly for men from a rural background and the least privileged socioeconomic categories (Li, Zhang, Yang, & Attané, 2010; Wei & Zhang, 2015); however, some, who still harbor the goal of marrying, find themselves forced to put off their plans for marriage or even give up on them altogether (Das Gupta, Ebenstein, & Sharygin, 2013).

Whether women’s social status is enhanced in such contexts should be questioned, as an advance in social mobility is not the same as having gender-equal relationships with a spouse. Yet, compared to class relations, gender relations in high sex-ratio settings have rarely been studied. This study aims to fill this knowledge gap by describing the characteristics and attitudes of single men who had passed prime marriage age, in three rural and disadvantaged counties of southern Shaanxi in China particularly affected by the male marriage squeeze. More specifically, it aims to assess if the men who wish to marry but face difficulties in achieving this goal are more or less gender equal in their attitudes than married men and, if so, in what ways. While answering these questions does not offer any firm clues to the causal impact of high sex ratios on gender relations, it provides new insights into what characterizes marriage-squeezed men, who are assumed to feel stressed about finding a wife beyond their class position. It thus makes some contribution to the literature on gender (in)equality in settings where men are in competition to meet women for long-term partnerships.

Literature Review

Gender Relations in High Sex-Ratio Contexts

The seminal work by Guttentag and Secord (1983) has put forward the sex ratio theory to demonstrate that the position of women in various societies is closely related to the respective numerical weight of men and women in the population. One of their most prominent conclusions is that women in high sex-ratio communities should have more dyadic power in negotiating a relationship because both men and women know that there are alternative partners available to women. Hence, they use their numeric under-representation to gain ascendancy in their class position, as also suggested by more recent research (Angrist, 2002; Du et al., 2015). In turn, men’s bargaining power in terms of mate selection is low as scarce women have power over men who depend upon women as romantic partners, wives, and mothers. Guttentag and Secord (1983) also show that, although women in high sex-ratio societies may be highly valued and respected, men may simultaneously attempt to limit their structural power by impeding their economic and political participation. A consistent conclusion was drawn by South and Trent (1988), who suggested that the value of women in high sex-ratio communities might paradoxically limit their life options, especially because of their low labor-force participation; this was also found by Chang, Connelly, and Ma (2016) in the Taiwanese context, and by Angrist (2002) in the U.S. Moreover, in high sex-ratio contexts, women may use their bargaining power not only in terms of mate selection but also within marriage.

In sum, most empirical studies suggest that women and men in high sex-ratio communities adopt complementary roles, with women being reinforced in their role of homemakers and mothers, and men in their role as family breadwinners. While Guttentag and Secord (1983) attribute this situation to structural power, with men possessing more authority to shape norms that reinforce their power position, Bulte, Tu, and List (2015) explain this polarizing trend through an individualistic perspective: women, aware of their advantage in mate selection, “respond by investing less in developing independent means of support […]. Men, in contrast, face a much more competitive marriage market and invest greater amounts.” (p. 144) However, the available empirical data suggest that, within marriage, women’s status is enhanced mostly in relation to their roles as wives and mothers, while they “lose out” in terms of labor market participation (Du et al., 2015; Jin, Liu, Li, Feldman, & Li, 2013; Wei & Zhang, 2015).

From this, one can assume that in high sex-ratio contexts, both women and men may have stereotyped views of gender roles where women are associated with the domestic sphere and men with the public sphere. To date, however, this issue has received very little academic attention. Most available studies address potential effects on men’s and women’s respective power relations in terms of mate selection (Eklund & Attané, 2017), but do not account for the ways in which relationships are gendered. Moreover, a major shortcoming in the sex ratio theory is that it considers all men in high sex-ratio settings as a homogenous group and does not make any distinction between them according to their socioeconomic characteristics and their attitudes in other domains. More specifically, empirical evidence is needed about China to understand how men assign gender roles at the individual level when they have to compete for scarcer single women, who leverage their numeric disadvantage for negotiating upward social mobility through marriage. However, not all men are affected in the same way. Although high sex ratios characterize most of China in relation to long-standing gender inequalities (Table 1), a man’s chances of marrying are nonetheless lower if he lives in the countryside, especially if he is poor (Li et al., 2010). Indeed, the fact that women can migrate to a city or another province more easily than before means that single women now have a wider choice of potential husbands. Therefore, they tend to choose men who can provide them with material comforts, namely, those who are more often than not city dwellers (Liu, 2016).

Unequal Gender Assignments in China

The public and private spheres are two distinct arenas where men and women operate on a daily basis, but rarely on an equal footing. Research has shown that opportunities for women in the public sphere are dependent on the assignment of gender roles within marriage, and central aspects of the relationship between husband and wife are their respective contributions to the monetary economy of the household, and the division between labor and domestic tasks (Liu, 2007; Wei, 2011). In China, the government’s stance on the rights of women and gender equality in recent decades has not put an end to traditional stereotypes of the roles and duties of men and women within the family and society or to the often very unequal situations they generate, in particular since the economic reforms that created conflicting gender ideologies (Ji, 2015; Wang, 2010). Society still assigns well-defined roles and spheres of influence to men and women (Attané, 2012; Evans & Strauss, 2011; Qian & Qian, 2014; Yang, 2015) and, although in certain respects, notably regarding education and health, improvements in the situation of Chinese women are indisputable (Ji, 2015), they are still treated unequally, especially in relation to employment, inheritance, wages, and decision-making within the family (Burnett, 2010; Du et al. 2015; Sargeson, 2012; Shu, Zhu, & Zhang, 2012). This makes the sex ratio theory partially relevant with regard to China, as women’s relationships with men remain all the more unequal for being part of a demographic context that is unfavorable to them, notably the high sex ratios that result from gender-based discrimination (Table 1). In turn, although the issue has never been subject to exhaustive research to our knowledge, a possibility is that unequal gender assignments in Chinese families stem at least partly from the long-standing high sex ratios (Attané, 2013), as suggested by the sex ratio theory. Overall, the fact remains that, although no direct causality can be established with the sex ratio imbalance owing to a lack of appropriate data, the roles of the husband as the economic mainstay of the family and that of the wife centered on children and domestic tasks remain firmly anchored in marital practices and in the expectations that spouses have of each other (All-China Women Federation [ACWF], 2010; Zuo, 2009); this is also the case for urban China where gender ideology and gendered patterns of inequality remain salient determinants of relations between spouses (Shu et al., 2012). However, research suggests that men are more likely than women to hold such stereotyped attitudes, placing little value on the educational attainment and financial prospects of a potential spouse, and preferring women who are able to take on maternal and homemaker roles (Qian & Qian, 2014; Tu & Chang, 2000). In addition, although individuals with higher education are more likely to hold egalitarian gender attitudes, the educational effect is stronger for women than for men (Shu, 2004).

Survey Description and Limitations

This study draws on quantitative data from the DefiChine survey (Attané, 2018) designed to investigate various aspects of the living conditions, behavior, and attitudes of ever- and never-married men in disadvantaged and high sex-ratio rural settings in China. The aim is to achieve a better understanding of the socioeconomic circumstances associated with men’s (in)ability to form intimate relationships when women are locally less numerous than them. The survey was conducted in 2014–2015 in three rural counties of Ankang city in southern Shaanxi selected because of their high sex ratios as compared to both rural Shaanxi and rural China as a whole (Table 1). This is especially true among the never-married population aged 15 or above; the sex ratio in this broad age group ranges from 158 men per 100 women in Hanbin to 183 in Xunyang and 185 in Shiquan, versus 151 in rural Shaanxi and 149 in rural China as a whole in 2010.

Appropriate disaggregated data are missing that could precisely assess the causes of such high sex ratios in this region. However, such high sex ratios in the adult population are likely to stem partly from the very high sex ratios among children (themselves resulting from high sex ratios at birth starting from the late 1980s), which spilled over into the adult population as people aged (Table 1) and, hypothetically, from the female emigration from these disadvantaged areas partly driven by their quest for upward mobility through marriage. These districts are indeed marked by poverty, which is one of the most prominent discriminatory factors in men’s access to marriage at the individual level in China (Li et al., 2010); they are located within a zone classified as a priority for poverty reduction and development by the central government (Colin, 2013), with a per capita GDP of less than 13,000 CNY in 2010―that is, less than half the average of Shaanxi province (about 27,100 CNY, compared to about 30,000 CNY in China as a whole) (SBS, 2011).

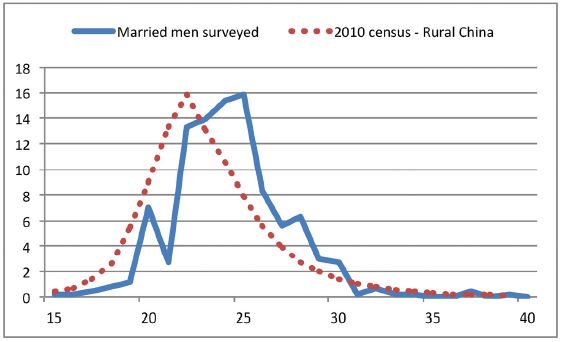

The sample was recruited using conventional probability sampling methods from a sampling frame consisting of the family planning administration registers at the county level. Two sub-samples were selected using disproportionate stratified random sampling: one consisting of ever-married men, and the other of single men who had passed prime marriage age in China. The survey included only men aged 28–59 years, which is in line with previous research suggesting that in rural China a man’s chance to marry decreases significantly after age 28 (Jin et al., 2013). Beyond this age, men pass a symbolic threshold beyond which they may find it increasingly difficult to marry and may end up as lifelong bachelors. The age of 28 is also a cut-off point in our sample of married respondents, as 91.3% married before this age (Figure 1). To identify their characteristics and to allow meaningful comparisons with married men, the never-married men were deliberately oversampled. In addition, 31 qualitative semi-structured interviews were conducted, some excerpts of which are reproduced throughout the text to support the quantitative results. To get a better understanding of respondents’ attitudes throughout various stages of the life cycle, some younger men (aged below 28) were included in the qualitative sample. The quantitative questionnaire was administered to 1,419 men, among whom 67 dropped out or were not successfully interviewed (a response rate of 95.4% and 1,352 valid questionnaires). Sampling weights were calculated to adjust for unequal selection probability and non-coverage, and involved calibration of the sample’s age distribution by marital status to match the values of rural Shaanxi in the 2010 census. All the analyses use the adjusted samples.

To get a clearer focus on the marriage-squeezed men, this article includes only the never-married men who wish to marry but reported difficulties in doing so––mainly because of the shortage of available female partners at the local level and/or because they are too poor to afford marriage––hereafter called the “involuntary” bachelors (N = 375). They are compared to the currently married men, including those remarried, engaged or in a cohabiting union (hereafter called the “married men”) (N = 656) but excluding divorced or widowed and not remarried men (who account for 7.7% of our sample) because their current attitudes might be influenced by their past experience of marital life. As the numerical decrease in the later cohorts has exacerbated the existing sex imbalance on the marriage market owing to the fact that Chinese men marry women a few years younger than themselves, and in order to reduce various biases due to age, generation, and marriage duration effects, the descriptive analyses consider two age groups: men aged 28 to 42 (born after 1973, when fertility in China began to fall sharply), and men aged 43 to 59 (born when fertility stood at 5 to 6 children per woman).

Survey Limitations

The analyses below are based on the assumption that the attitudes of each respondent are potentially influenced by the relative scarcity of women in the counties surveyed. However, no causal link between high sex ratios and changes in attitudes can be established because of a lack of appropriate data for comparing them with men in other regions where sex ratios are balanced. As our cross-sectional survey includes only a limited amount of biographical information, only men’s current characteristics can be described without considering the possible influence of their past experiences on their current attitudes, and with no possibility to assess if and how these may have changed over time. Hence, the analyses below provide important insights into the characteristics of the involuntary bachelors who had passed prime marriage age, and their differences with respect to the currently married men in these disadvantaged and high sex ratios settings. We must bear in mind, however, that findings shed light on a regional situation and therefore should not be generalized to rural China at large.

To ensure a common set of questions to married and single men―the latter being unable to describe their interactions with a woman in the private sphere as they have, by definition, no experience of formal cohabitation within marriage―only questions related to attitudes were asked. Hence, findings should be interpreted bearing in mind that gender equality as captured here derives from men’s attitudes and beliefs; the gender division of responsibilities and tasks in the home and the role of women in the labor market were not considered, and neither were the women’s perspectives.

Methods and Measurements

Men’s gender attitudes were measured on the basis of a set of questions selected because they address the most salient gender stereotypes highlighted in the relevant literature on China (ACWF, 2010; Attané, 2012; Evans & Strauss, 2011), namely their perception of women’s position and roles in the family versus society, and some interactions between husband and wife in the domestic and intimate spheres. To adapt the questions as closely as possible to the situation in China, two questions (Table 3) were drawn from the ACWF surveys (ACWF, 2010), two questions were picked from the value module of the World Value Surveys, and the remainder were devised specifically for our survey. Four response categories were used by respondents (strongly agree, agree, disagree, or strongly disagree). The dependent variable on gender attitudes was constructed by aggregating four questions (“Men are turned toward society, women devote themselves to their family”; “For a woman, a good marriage is better than a career”; “When jobs are scarce, men should have more rights to jobs than women”; and “During sexual intercourse, men should take the initiative, women should be submissive”), on which there are significant differences between married and never-married men. The respondents who agreed with each of the most inegalitarian statements (by ticking strongly agree or agree) or disagreed with each of the most egalitarian ones (by ticking disagree or strongly disagree) were classified as conservative, meaning that their attitudes were unfavorable to gender equality in both the private and public spheres; those who agreed or strongly agreed with each of the most egalitarian statements or disagreed or strongly disagreed with each of the most unegalitarian ones were classified as egalitarian, meaning that their attitudes were in favor of gender equality; the remaining respondents were considered to have open attitudes. Social relations were measured on the basis of participation in a birth, a zhousui (a ceremony to celebrate a child’s first birthday) or a birthday ceremony in the year preceding the survey, and by the frequency of visits to friends to chat, or have a drink or a meal in the month preceding the survey. As the perpetuation of patriarchal traditions is still a major family concern of Chinese families (Liu, 2007), a measure of adherence to patrilineal customs (by aggregating the variables A woman with no child is not complete, A wife must care for her parents-in-law, and Family property should be equally shared between daughters and sons after the parents’ death, with the respondents ranked using the same logic as above for gender attitudes) was considered.

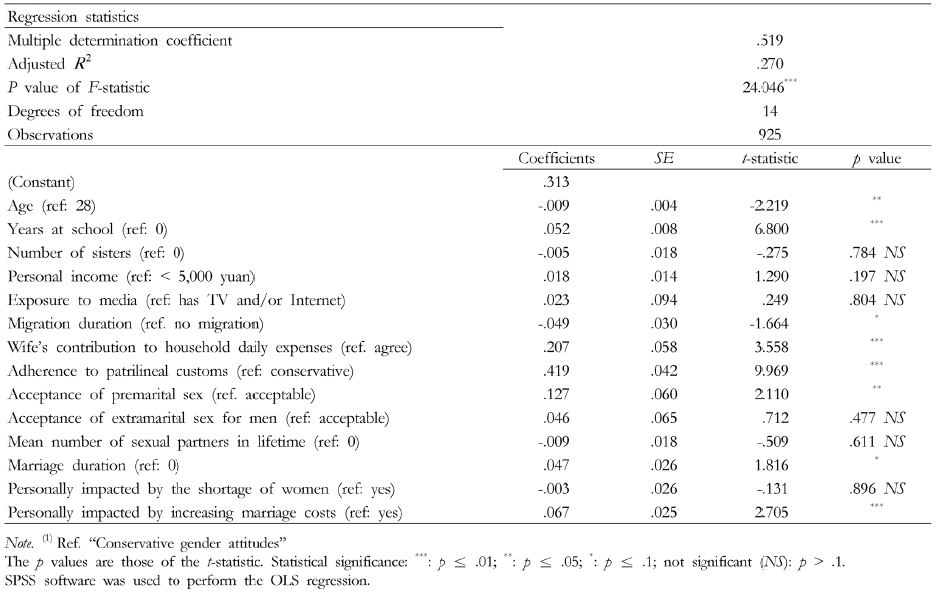

The Ordinary Least Square (OLS) regression analyzes the association between gender attitudes and independent variables pertaining to men’s profile, such as age, education, number of sisters, income, migration, marriage duration (rated zero for the never-married), and access to media (as measured by the presence of a TV set and/or the Internet in the home). The analysis also included variables with information about the organization of intimate behaviors as they provided insight into gender relations. Last, men’s perception of their own situation on a competitive marriage market was addressed by the variables Are you personally impacted by the shortage of women? and Are you personally impacted by increasing marriage costs?

Sample Description

The younger involuntary bachelors spent only 6.3 years at school on average―that is, four years fewer than the married men (10.2 years)―but the gap is even greater among the older men (3.7 and 8.9 years, respectively). The involuntary bachelors are poorer than the married men (with incomes around 30% lower, regardless of age) (Table 2). Yet in both age groups, they are more likely to have ever-migrated and also to have spent more time as migrants (6.2 years for the younger and 5.7 years for the older, against 5.0 and 3.8 years for the married, respectively), thus minimizing the overall inequality-reducing effect of internal migration in the sending areas (Ha, Yi, & Zhang, 2009).

Involuntary bachelors’ material conditions are also consistently worse than those of married men: they are more likely to live in a poorly equipped home, with slightly less than half of the younger and one third of the older men having both tap water and individual toilets (versus 80.0% of the married men). Last, they are also more likely to experience multidimensional isolation as defined by the intensity of interpersonal contacts and contacts with the outside world: they not only have less access to media than married men (although the gap is much greater among the older men), but are also more socially isolated as only one in three of the younger involuntary bachelors and one in five of the older group have frequent social relationships (versus around one in two married men). Socioeconomically, they are clearly at a disadvantage as compared to their currently married counterparts, which is consistent with other studies (Attané et al., 2013; Li et al., 2010; Wei & Zhang, 2015); they are also more conservative with respect to patrilineal customs and, although attachment to the norm of universal marriage is widespread among all respondents, this is even more true among the single ones (Table 2).

Results

Private versus Public Sphere

As shown by the Surveys on the Social Status of Women conducted by the All-China Women Federation (ACWF, 2010), Chinese men tend to hold stereotypical views with respect to men and women’s respective roles in the private and public spheres (Attané, 2012). Our findings confirm this statement, as one in two respondents (48.6% of the total sample) holds conservative gender attitudes. Hongbo, a married man aged 40 who graduated from upper middle school, for instance, clearly dissociated men’s and women’s roles: “[My wife] mainly takes care of the children, manages the family, educates the next generation, makes arrangements for the family. I mainly do business on the outside. That’s the basic division of labor.”

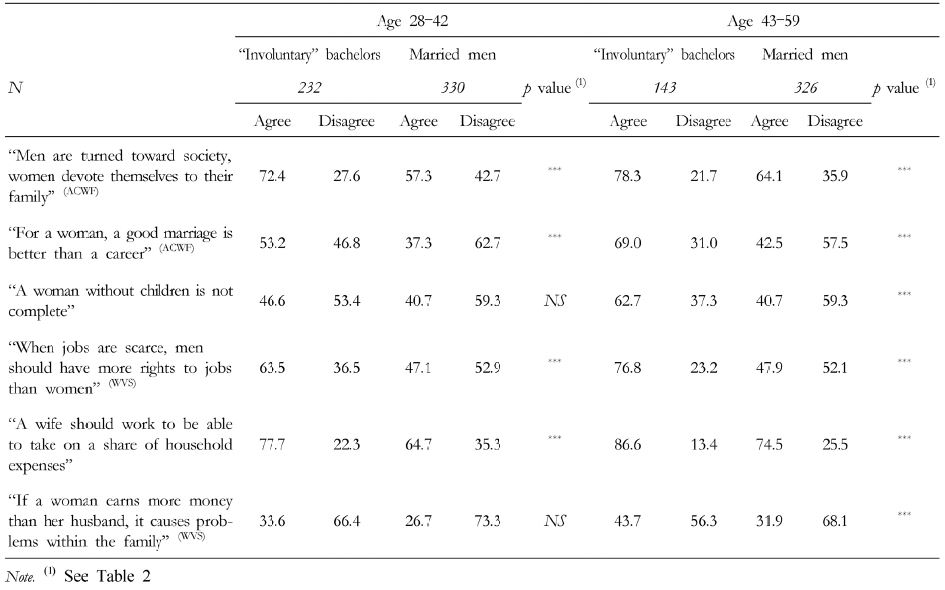

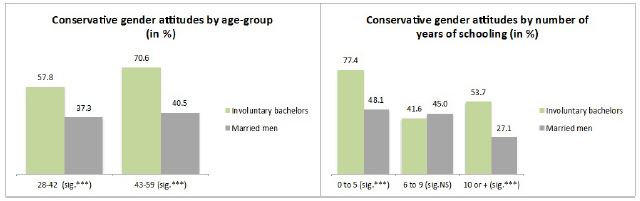

However, the men surveyed do not form a homogenous group in this respect. As with socioeconomic characteristics, marital status and generation are two important elements of the divide, as married men overall have much less conservative views than the involuntary bachelors; the divide is even greater among the older respondents (Figure 2). A majority of married men still agree that “Men are turned toward society, women devote themselves to their family” (57.3% of the younger group and 64.1% of the older group), but this idea is even more prevalent among the involuntary bachelors (72.4 and 78.3%, respectively) (Table 3). This notion, which prioritizes women’s roles in the domestic sphere, is reinforced by the fact that more than one in three married men (40.7% regardless of age) considers that “A woman with no child is not complete,” but, again, this idea is more widespread among the involuntary bachelors, who show a huge generational gap (46.6 of the younger group and 62.7% of the older group). The role of women as wives and mothers is indeed still deeply entrenched in attitudes, as illustrated by Cai, another married respondent (age 31): “If a woman marries into your family, you do well and support her. […] If she gives birth to a fat baby, then she’s fulfilled her mission.”

Men who have conservative gender attitudes. Note. Statistical significance: ***: p ≤ .01; **: p ≤ .05; *: p ≤ .1; not significant (NS): p > .1.

Statements Reflecting Respondents' Attitudes toward Gender Equality in the Public versus the Private Sphere (%)

Such stereotyped attitudes are observed in other statements, including from married men, that similarly pertain to the notion that men should be the main family breadwinners, and suggest that women’s autonomy through employment should not be the norm. Guo, another married respondent, points to the deep-seated internalization of women’s economic dependence on their husband: “A man should earn money to support his family. He should be responsible for the family’s future, should rush around on their behalf. […] Although [my wife is] a modern woman, she doesn’ have to bear the economic burden for the family” (age 33, college graduate). This is also the case for Cong (married, age 28), who emphasizes the strong social injunction to comply with gendered roles in this region: “This is very deeply rooted. […] Men should support their families. […] If you let your wife work away from home and you yourself raise a kid at home, they [local people] will say you’re useless.” Wang Fei, who has not passed prime marriage age, shares similar views but goes a step further by suggesting that a man who takes on domestic chores would endanger his masculine identity: “I’ve seen them [bachelors] washing their clothes and cooking […]. How can I put it? Away from home he’s a man, but at home he’s a woman” (age 24, never married, lower middle school).

The results of the quantitative analyses give further evidence of the strong adherence to such stereotyped gender assignments at the aggregated level: more than one in three married men still considers that “For women, a good marriage is better than a career,” and almost one in two that “When jobs are scarce, men should have more rights to jobs than women” (Table 3); again, the involuntary bachelors more frequently hold such conceptions in both age groups (63.5 and 76.8%, respectively). Consistently, they are also less likely to distance themselves from the strong social injunction to comply with gender assignments in this region, as they consider more frequently than the married men that “If a woman earns more money than her husband, it causes problems within the family” (33.6 and 43.7%, versus 26.7 and 31.9 of the married men). The only case in which they appear to be less conservative than their married counterparts is in regard to women’s economic contribution, as a larger share considers that “A wife should work to be able to take on a share of household expenses” (77.7% of those aged 28–42 and 86.6% of those aged 43–59 versus 64.7 and 74.5% of the married men, respectively).

Although conservative gender attitudes prevail among both married and never-married men, such views are even more anchored among some of the single interviewees who expressed their difficulty in finding a spouse. Houde, a single man aged 34 years, for instance, describes himself as “not hoping for too much.” However, his requirements are clearly for a woman who will be a mother and housewife within the domestic sphere, without making any reference to the need for emotional commitment: “It’s enough if she [a wife] can take care of the home. I don’t expect her to do other things for me. It’s enough if she can take proper care of the home. […] I have to marry, […] to have someone to wash clothes and cook meals. That’s all.” This is also the case for Yang, a single man aged 41 who attended only primary school and has been looking for a wife for several years. He regards mate selection in a utilitarian way, with mainly material considerations with respect to marriage: “It’s not that I want to find a very good one―just so long as she can do housework and show filial respect to my mom. With the way we are, how am I going to ask for someone so good? […] My ideal [wife][…] She would just have to be able to bear hardships, be able to show filial respect to parents, cook for me, and handle the housework.”

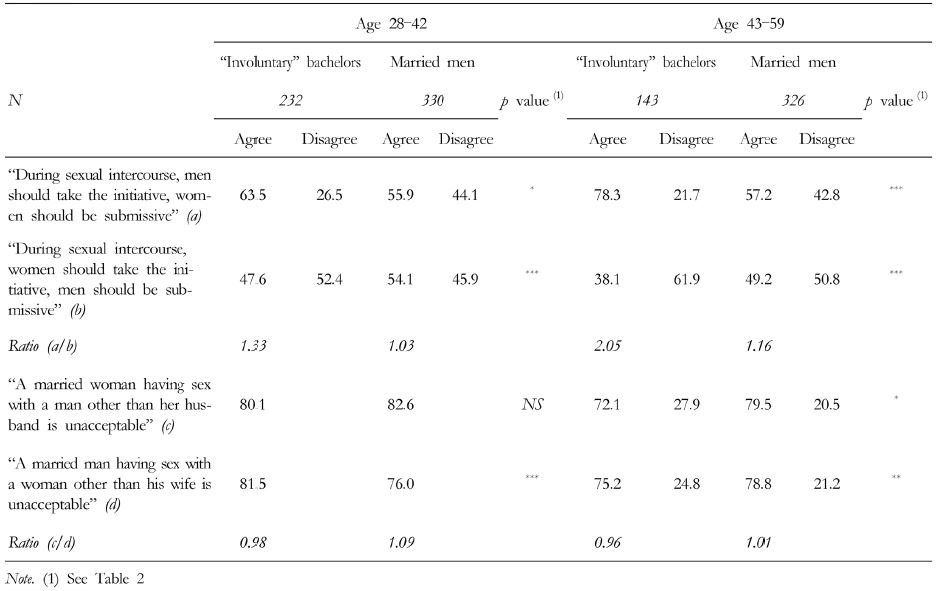

The Intimate Sphere

Male domination is also deeply entrenched in attitudes in the region studied when it comes to intimate relationships with women. More than two in three involuntary bachelors consider that “During sexual intercourse, men should take the initiative, women should be submissive,” as compared to slightly more than the half of the married men (Table 4). Consistently, they are less likely to agree with the opposite statement “During sexual intercourse, women should take the initiative, men should be submissive.” Interestingly, the married men are also more gender equal in this respect because they consider that during sexual intercourse the initiative should be taken by the man or the woman almost to an equal extent (with a ratio measuring the asymmetry between the sexes of around 1, as shown in Table 4), while the involuntary bachelors more frequently agree with the fact that men should take the initiative, but not women (with a ratio of 1.33 among the younger group and 2.05 among the older group). Attitudes differ much less strongly, however, when considering extramarital relationships, which are judged as unacceptable for both men and women by the overwhelming majority of the respondents, regardless of marital status. The only striking difference appears between the younger generations of respondents, with the married men being much more tolerant toward men having extramarital relationships (76.0% consider that such relationships are unacceptable, versus 81.5% of the involuntary bachelors). While the involuntary bachelors are a little less intolerant than their married counterparts toward women having extramarital relationships, the differences are not always significant; although it cannot be established from our data, this suggests that some of them see married women as potential partners.

Attitudes Related to the Patriarchal System

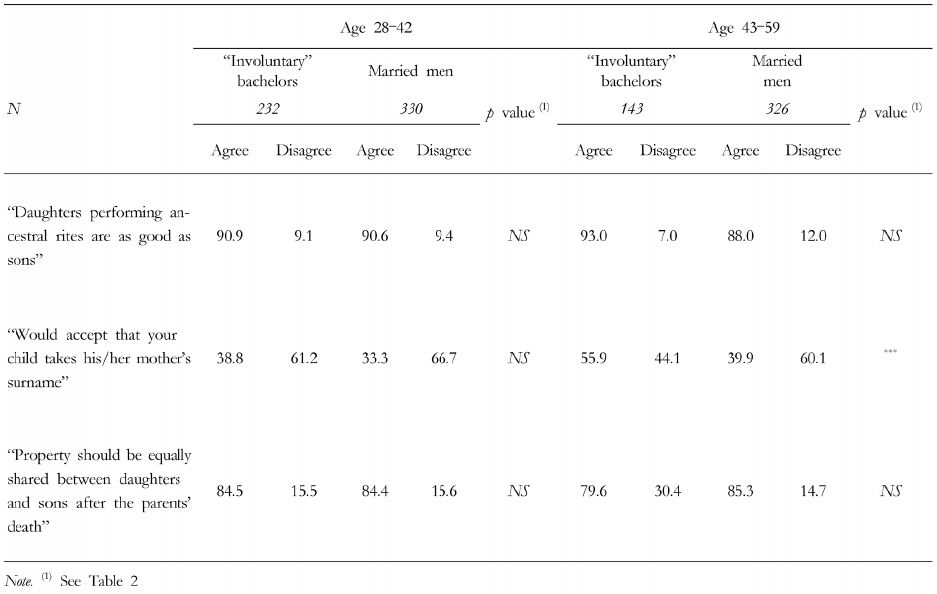

China’s patriarchal system, marked by the continuation of the family line and a filiation system that favors sons, still dominates daily life and contributes to maintaining women under male domination in various aspects of society and family organization (Attané, 2012; Yeung & Shu, 2016). Consistently, adherence to patrilineal customs is strong in the districts surveyed, where around one in two respondents (51.5% of the total sample) has conservative attitudes in this respect, with no significant difference between the two marital status groups among the younger men (Table 2). Moreover, in this region where marriage is still widely accepted as a predominant norm, nearly two in three (62.7% of the total sample) consider that the impossibility of continuing the family line is among the hardest situations for single men to bear. However, although they hold more conservative attitudes in other respects, the involuntary bachelors are as gender equal as their married counterparts with respect to ancestor worship and inheritance, with at least eight in ten agreeing that “Daughters performing ancestral rites are as good as sons” and that “Property should be equally shared between daughters and sons after the parents’ death” (Table 5); this suggests that daughters would not be particularly discriminated against in this respect in the region.

Statements Reflecting Respondents' Attitudes toward Gender Equality in Practices Related to the Patrilineal System (%)

Interestingly, however, while the married and the younger single men are not very different in being negative about the idea of breaking with patrilineal customs by accepting that their child takes his/her mother’s surname, single men show a strong generation effect; this greater acceptance might reflect an adaptation to the marriage squeeze by the men seeking to marry, and this assumption is supported by the fact that the difference is greater and significant only among the older involuntary bachelors, who are assumed to have spent more years seeking a wife.

Who Are the Men with Conservative Gender Attitudes?

In line with studies in other regions (Shu, 2004; Tu & Chang, 2000; Yang, 2016), generation and level of education are strong determinants of gender attitudes in the counties surveyed, with the younger and more educated men being less conservative than other men in both marital status groups (Figure 2).

The positive relationship between education and men’s gender attitudes is confirmed by the multiple regression (Table 6): the higher the number of years spent at school, the greater the likelihood of having gender-equal attitudes. Interestingly, the number of sisters is not significantly related to gender attitudes; having been raised with girls does not make their brother’s attitudes more gender equal. The regression does not confirm an effect of income per se but economic concerns are nonetheless present as the men with conservative gender attitudes are more likely to be personally impacted by increasing marriage costs, suggesting that economic obstacles to marriage–– including among men who ended up getting married––are associated with such stereotyped views. Interestingly, contrary to what is reported for instance in Germany and Canada (e.g., Fox, 2001; Grunow, Schultz, & Blossfeld, 2012), a longer marriage duration is associated with more gender-equal attitudes, suggesting that relations within marriage may be renegotiated in everyday interactions between spouses in a direction more favorable to gender equality. Gender attitudes are also related to migration experiences, but not in the expected direction: the longer the period spent in migration, the more conservative the gender attitudes. This challenges the idea that exposure to alternative lifestyles through migration necessarily makes people less conservative and more open to change, as shown in other contexts (Khalid, 2011). Although this points to a possible selection bias in internal migration in the region with the less educated men being more likely to migrate to improve their living standards (Zhang, 2004), this cannot be further investigated from our cross-sectional data, which do not provide information about men’s characteristics before migration.

Multiple Regression (OLS) of the Determinants of Gender Attitudes (1) among “Involuntary” Bachelors and married Men

Moreover, the positive and significant relationship between conservative gender attitudes and men’s expectations about women’s economic contribution to household daily expenses confirms the disconnection between such expectations and any real desire to increase women’s autonomy or any belief in gender equality between spouses. Instead, as stated earlier, it probably reflects a need to improve the family’s economic situation after marriage among the poorest section of the male population.

Discussion

In line with existing research about China, most of our respondents, regardless of marital status, frame their gender attitudes in relation to stereotypical roles pertaining to male domination in various aspects of family and social organization; attitudes whereby the husband is seen as the economic mainstay of the family while the wife is centered on the domestic sphere are still firmly rooted, something that might be related to the long-standing high sex ratios in the region, as suggested by the sex ratio theory. Hence, unlike the trend in some Western societies where women’s work outside the home, like that of men, is increasingly judged to be more valuable than their domestic roles (Zuo & Bian, 2001), this tendency is barely visible in the region surveyed. The centrality of marriage, gendered roles, and non-market unpaid labor for women reported for other regions in China (Mukherjee, 2015; Shu et al., 2012) remains strong among our respondents, but this general picture needs to be qualified as generation and education are salient determinants of attitudes beyond marital status itself. Overall, the marriage-squeezed men report more conservative gender attitudes than their married counterparts mainly because they are comparatively less educated, more conservative with respect to the patrilineal organization of society, and not exposed to marital life which, all other things being equal, tends to make men more gender egalitarian in this region. Previous research has shown that involuntary bachelors are mostly from poorer rural backgrounds, with low education and income levels (Das Gupta et al., 2013; Li et al., 2010). This body of research also suggests that the marriage squeeze has a stratifying effect: by failing to marry, single men become even poorer; the longer marriage is delayed and the poorer they are, the more difficult it is for them to find a wife. Long-term singlehood thus perpetuates poverty for men who are already poor, but our findings suggest that it might also reinforce stereotyped expectations of women’s roles among men who already hold unequal gender attitudes that stem from behaviors and beliefs constructed throughout life. Hence, they point to the possibility that marriage- squeezed men might be more likely to confine women largely to the private world of the home to carry out housework, as they tend to have a utilitarian view of marriage. Paradoxically, they also have higher expectations about women’s economic contribution than their married counterparts. Again, this confirms the stratifying effect of marriage: the marriage-squeezed men are seeking, in a sense, to escape poverty through marriage. Women’s economic participation is a valuable measure of gender equality within the family as it reflects the division between labor and domestic tasks between spouses to some extent (Liu, 2007; Wei, 2011). Consequently, if these men finally end up marrying, this specific expectation might, theoretically, have some positive long-term impact on women's financial autonomy. It remains to be seen, however, if, via a knock-on effect, women would take advantage of this to claim more gender equality within the family. However, a positive sign for women is that although most other attitudes of marriage-squeezed men are more conservative, they would be at least as likely as their married counterparts to distance themselves from patrilineal customs by allowing more or less gender-equal inheritance rights and ritual duties to both daughters and sons; together with the fact that, as they age, the involuntary bachelors are more likely to give up on passing on their name to their child, this suggests that renunciation of patriarchal family organization in favor of women would be among the most immediate adaptations to the marriage squeeze.

Conclusion

In sum, the marriage-squeezed men in the region surveyed are less gender equal in their attitudes than their married counterparts, but their difficulties in marrying are far from being the only determinant. This result invites us to reconsider the sex ratio theory by adopting a more intersectional approach that takes into account the heterogeneity of the male population, in particular when it comes to their individual circumstances (including their socioeconomic characteristics), and attitudes in other domains. Nevertheless, various questions are left unanswered by our cross-sectional data. In particular, our results invite further consideration of the effects of high sex ratios from a gender perspective by using biographical data to identify how men’s attitudes and expectations change at different stages of their lives, before and after marriage, as well as some causality effects. It would also be worth investigating the factors behind the more gender-equal attitudes of married men. These may be driven by determinants other than education alone, in particular if―and if so, how―they are driven by women who use their numeric disadvantage as leverage for increasing their dyadic power within marriage in these disadvantaged settings with high sex ratios.

References

- All-China Women Federation (ACWF), (2010), Report on the results of the 3rd survey on Chinese women, Retrieved October 14, 2017, from http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/tjgb/qttjgb/qgqttjgb/200203/t20020331_30606.html or http://acwf.people.com.cn/GB/99061/233094/.

- Angrist, J., (2002), How do sex ratios affect marriage and labor markets?, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(3), p997-1038.

- Attane, I., (2012), Being a woman in China today, China Perspectives, 4(5), p5-15.

- Attane, I., (2013), The demographic masculinization of China: Hoping for a son, Heidelberg, Springer.

- Attane, I., Zhang, Q. L., Li, S. Z., Yang, X. Y., & Guilmoto, C., (2013), Bachelorhood and sexuality in a context of female dearth: Evidence from a survey in rural Anhui, China, The China Quarterly, 215, p703-726.

- Attane, I., (2018), Being a single man in rural China, Population & Societies, 557, p1-4.

-

Bulte, E., Tu, Q., & List, J., (2015), Battle of the sexes: How sex ratios affect female bargaining power, Economic Development and Cultural Change, 64(1), p143-161.

[https://doi.org/10.1086/682706]

- Burnett, J., (2010), Women’s employment rights in China: Creating harmony for women in the workplace, Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, 17(2), p289-318.

-

Chang, S., Connelly, R., & Ma, P., (2016), What will you do if I say ‘I do’?: The effect of the sex ratio on time use within Taiwanese married couples, Population Research and Policy Review, 35(4), p471-500.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-016-9393-1]

- Colin, S., (2013), Le defi rural du ‘reve chinois’, Herodote, 3(150), p9-26, (In French).

- Das Gupta, M., Ebenstein, A., & Sharygin, E., (2013), Implications of China’s future bride dearth for the geographical distribution and social protection needs of never- married men, Population Studies, 67(1), p39-59.

- Du, J., Wang, Y., & Zhang, Y., (2015), Sex imbalance, marital matching and intra- household bargaining, China Economic Review, 35, p197-218.

- Eklund, L., & Attane, I., (2017), Marriage squeeze and mate selection, In X. Zang, & L. X. Zhao (Eds.), Handbook on marriage and the family in China, p156-174, London, Sage.

- Evans, H., & Strauss, J. C., (2011), Gender in flux: Agency and its limits in contemporary China, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

-

Fox, B., (2001), The formative years: How parenthood creates gender, Canadian Review of Sociology, 38(4), p373-390.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-618x.2001.tb00978.x]

-

Grunow, D., Schultz, F., & Blossfeld, H. P., (2012), What determines change in the division of housework over the course of marriage?, International Sociology, 27(3), p289-307.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580911423056]

- Guttentag, M., & Secord, P. L., (1983), Too many women? The sex ratio question, California, Sage.

-

Ha, W., Yi, J. J., & Zhang, J. S., (2009), Inequality and internal migration in China: Evidence from village panel data, Human Development Research Paper 2009/27, United Nations Development Programme, Retrieved August 12, 2018, from http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/inequality-and-internal-migration-china.

[https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1458960]

-

Ji, Y. C., (2015), Between tradition and modernity: “Leftover” women in Shanghai, Journal of Marriage and the Family, 77(5), p1057-1073.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12220]

-

Ji, Y. C., & Yeung, W. J., (2014), Heterogeneity in contemporary Chinese marriage, Journal of Family Issue, 35(8), p1662-1682.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513x14538030]

- Jin, X. Y., Liu, L. G., Li, Y., Feldman, M. W., & Li, S. Z., (2013), “Bare branches” and the marriage market in rural China: Preliminary evidence from a village survey, Chinese Sociological Review, 46(1), p83-104.

- Khalid, R., (2011), Changes in perception of gender roles: Returned migrants, Pakistan Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 9, p16-20.

- Li, S. Z., Zhang, Q. L., Yang, X. Y., & Attane, I., (2010), Male singlehood, poverty and sexuality in rural China: An exploratory survey, Population-E, 65(4), p679-694.

- Liu, J. Y., (2007), Gender and work in urban China. Women workers of the unlucky generation, London, Routledge.

- Liu, L., (2016), Gender, rural-urban inequality, and intermarriage in China, Social Force, 95(2), p639-662.

-

Mu, Z., & Xie, Y., (2014), Marital age homogamy in China: A reversal of trend in the reform era?, Social Science Research, 44, p141-157.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2013.11.005]

- Mukherjee, S. S., (2015), More educated and more equal? A comparative analysis of female education and employment in Japan, China and India, Gender and Education, 27(7), p846-870.

- Population Census Office and National Bureau of Statistics of China (PCO), (2002), Zhongguo 2000 nian renkou pucha ziliao (Tabulation on the 2000 Population Census of the People’s Republic of China), Beijing, Zhongguo tongji chubanshe.

- Population Census Office and National Bureau of Statistics of China (PCO), (2012), Zhongguo 2010 nian renkou pucha ziliao (Tabulation on the 2010 Population Census of the People’s Republic of China), Beijing, Zhongguo tongji chubanshe.

-

Qian, Y., & Qian, Z. C., (2014), The gender divide in urban China: Singlehood and assortative mating by age and education, Demographic Research, 31(45), p1337-1364.

[https://doi.org/10.4054/demres.2014.31.45]

- Sargeson, S., (2012), Why women own less, and why it matters more in rural China’s urban transformation, China Perspectives, 4, p35-42.

- SBS, (2011), Shaanxi statistical yearbook, Shaanxi Bureau of Statistics, Beijing, China Statistics Press.

-

Shu, X., (2004), Education and gender egalitarianism: The case of China, Sociology of Education, 77(4), p311-336.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/003804070407700403]

- Shu, X. L., Zhu, Y. F., & Zhang, Z. X., (2012), Patriarchy, resources, and specialization: Marital decision-making power in urban China, Journal of Family Issues, 34(7), p885-917.

-

South, S. J., & Trent, K., (1988), Sex ratios and women’s roles: A cross-national analysis, American Journal of Sociology, 93(5), p1096-1115.

[https://doi.org/10.1086/228865]

- Tu, S. H., & Chang, Y. H., (2000, February), Women’s and men’s gender role attitudes in coastal China and Taiwan, Paper presented at East Asian Labor Markets Conference, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea.

- Wang, Z., (2010), Gender, employment, and women’s resistance, In E. J. Perry, & M. Selden (Eds.), Chinese society: Change, conflict and resistance, p162-186, London, Routledge.

- Wei, G. Y., (2011), Gender comparison of employment and career development in China, Asian Women, 27(1), p95-113.

-

Wei, Y., & Zhang, L., (2015), Involuntary bachelorhood in rural China, China Report, 51(1), p1-22.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0009445514557388]

- Yang, H., (2015), Gender and children’s housework time in China, Journal of Marriage and Family, 77, p1126-1143.

-

Yang, W. Y., (2016), Differences in gender-role attitudes between China and Taiwan, Asian Women, 32(4), p73-95.

[https://doi.org/10.14431/aw.2016.12.32.4.73]

-

Yeung, W. J., & Shu, H., (2016), Paradox in marriage values and behavior in contemporary China, Chinese Journal of Sociology, 2(3), p447-476.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/2057150x16659019]

-

Yu, J., & Xie, Y., (2015), Cohabitation in China: Trends and determinants, Population and Development Review, 41(4), p607-628.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2015.00087.x]

- Zhang, M., (2004), China’s poor regions: Rural-urban migration, poverty, economic reform and urbanisation, London, Routledge.

-

Zuo, J. P., & Bian, Y. J., (2001), Gendered resources, division of housework, and perceived fairness: A case in urban China, Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(4), p1122-1133.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.01122.x]

- Zuo, J. P., (2009), From revolutionary comrades to gendered partners: Marital construction of breadwinning in post-Mao urban China, Journal of Family Issues, 24, p314-337.

Biographical Note: Isabelle Attané is a Senior Researcher, demographer and sinologist at the French Institute for Demographic Studies (INED) in Paris, France. E-mail: attane@ined.fr

Biographical Note: Lisa Eklund is an Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology at Lund University, Sweden. E-mail: lisa.eklund@soc.lu.se

Biographical Note: Qunlin Zhang is an Associate Professor at Xi’an Polytechnic University, China. E-mail: zhangql616@163.com