Feminist Net-Activism as a New Type of Actor-Network that Creates Feminist Citizenship

Abstract

The spread of the #MeToo movement and protests against femicide have changed the digital media landscape in both global and Asian contexts. This paper aims to demonstrate that these changes are the product of a feminist, material-semiotic actor-network, and that feminist net-activism constitutes an ontological turn, an axiological intervention, and political participation, insofar as it (1) stimulates interaction between human and non-human entities; (2) actively redefines the paradigm of feminist discourse and practice; and (3) articulates feminist political issues and objectives and mobilizes political action through participatory platforms, such as online citizen initiatives. Hyper-connectivity and this ubiquitous digital media presence have broken clear boundaries, creating a new ecosystem where the feminist multitude emerges in a fourth wave of feminism constituted by digital content prosumers, using easily disseminated media to renew modalities of resistance and reshape the theoretical paradigm of feminism. The feminist multitude in the new media landscape advocates artistic creativity in the representation of the female body, which is not subjugated to the phallic economy of desire, and inscribes feminist issues and history in the digital archive.

Keywords:

net-activism, feminist actor-network, participatory platform, feminist citizenship, fourth wave feminismIntroduction

In our hyper-connected global society, the digital space is not only a virtual space but also a real space that affects our cognition, sensitivity, and action. This digital space has been called “a space of tensions and contradictions” (Fotopoulou, 2016, p. 1) that oscillates between domestication and liberation, concealment and disclosure, vulnerability and empowerment. Where once this space was dominated by hegemonic, macho network patterns, described as cybersexism (Penny, 2013; Poland, 2014), online misogyny (Jane, 2014), and gendered cyberhate (Jane, 2016), the digital media landscape has been reshaped by feminist practices such as the #MeToo movement and protests against femicide, transmuting sexist cyberspace into a space of feminist resistance. The #Metoo movement shines the spotlight on a widespread and established rape culture that occurs in everyday life and in all spaces, including cyberspace. Digital sexual harassment in cyberspace can be overlooked; this has become a subject of criticism and of social awareness. Investigating the severity of digital sexual harassment highlights the necessity of changing the digital landscape, which is currently deemed to be a macho sphere. In addition, the protest movement against femicide that harshly criticizes the increasing number of femicides in Argentina and France offers an opportunity to intensify feminist solidarity and denounce violence against women. The change in the digital media landscape brought by the feminist multitude demonstrates the pervading structure of domestic violence and emphasizes the urgency of eradicating this inequality.

This feminist net-activism signals the blossoming of fourth wave feminism (Baumgardner, 2011; Cochrane, 2013; Evans, 2015) that constitutes a “turning point for feminism” (Fotopoulou, 2016, p. 4). It objects to the “post-feminist moment” (Gill, 2007; McRobbie, 2009; Mendes, 2011; Ringrose, 2013; Scharff, 2012) because post-feminism suggests the death of feminism. Fourth wave feminism, as inscribed in the new media ecology, is characterized by “call-out” culture (Munro, 2013, p. 23), which archives everyday practices of sexism, discloses the absurdity of misogynistic culture, and subverts rape culture practices and thinking to challenge the gender regime. The critical dissection of everyday practices through the prism of feminism enables a revival of feminism in keeping with the spirit of the times. Fourth wave feminism is intersectional in that women’s social and political position, which consists of multiple facets of power, is characterized by their economic resources, symbolic capital, social status, digital accessibility, and health capital. Subtle differences among fourth wave activists promotes the dynamics of feminist activism that encourages the discussion concerning the purpose and the efficacity of discursive and practical strategies of feminist movement to flourish.

This study endeavors to analyze this phenomenon by charting the development and dynamics of fourth wave feminism in both the global and South Korean contexts. It does so by utilizing the Actor-Network Theory to explain contemporary practice-based feminist approaches that are difficult to analyze using traditional feminist theory, thereby making a significant contribution to feminist discourse.

First, this article examines feminist net-activism as a new type of actor-network. This digital practice also entails an ontological turn in the sense that net-activism is “a collective of humans and non-humans” (Latour, 1999, p. 296)—that is, an interaction of different entities, such as persons, cyber-territorialities, and digital social networks. Feminist net-activism cannot be reduced to communitarianism between humans because the feminist multitude is a “socio-technical ensemble” (Bijker, 1993) that involves both human and non-human agency. Hyper-connectivity and the ubiquitous digital media presence create a new ecosystem in which the feminist multitude and new media technologies co-constitute and reshape each other. Second, I explore how feminist net-activism is an axiological intervention that challenges the phallic order of value and meaning. By using digital media technologies as an arena for thought and a battlefield for obtaining visibility, the feminist multitude—as digital content “prosumers” (Toffler, 1980)—questions the value of beauty, renews the modes of resistance, and redefines the paradigm of feminist discourse and practice. Third, this article focuses on the political dimension of this activism and how it creates feminist citizenship as a material-semiotic actor-network. Feminist citizenship is not “[an] escape from embodiment” (Hansen, 2006; Nouraie-Simone, 2005), but a material practice of a collective of humans and non-humans that reconstitutes body politics through participatory platforms such as online citizen initiatives and petitions; it exists to influence and lobby the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. In summary, this article aims to explore the ontological, axiological, and political dimensions of feminist net-activism as understood as a material agency of digital connectivity.

Feminist Net-Activism as Ontological Turn Feminist Net-Activism as a Collective of Humans and Non-humans

The flourishing “century of feminism” began with multiple feminist strategies, such as the global #MeToo movement and the #EscapeTheCorset_Exhibition movement in South Korea. These strategies problematize the distinction between online and offline space because net-activism shapes offline activist practices (Mendes, Ringrose, & Keller, 2019, p. 33). The #MeToo movement is both a hashtag movement denouncing rape culture and an ongoing series of legal proceedings. The #EscapeTheCorset_Exhibition movement is both a reversal of “selfie” culture, which is distinct in cyberspace, and a daily practice of corporeal resistance to disciplinary power, which aspires to make the female body docile to subjugate it to the economy of phallic desire.

The digitalization of feminism has two stages, which are defined by the Web 1.0 era and the Web 2.0 era. In the Web 1.0 era, online and offline spaces seemed distinct and internet users were simply consumers of content provided by the servers. However, in the Web 2.0 era, hyper-connectivity breaks the boundaries between online and offline spaces and internet users are both consumers and creators of content. User-generated content launches the era of the participative social Web. This change emphasizes ontological challenges and implications, as hyper-connectivity is not an optional modality but a necessary ontological condition that guarantees social visibility in this era. The axiom of this era—“I am connected to social media; hence, I exist”—is what defines the ontological condition of this digital native generation. For this generation, the assemblage of their physical body, smartphone, internet, and social media space is what characterizes their individuality and their collectivity. In other words, their individual and collective social existence is determined by their digital connectivity.

The Web 2.0 era, however, caused turbulence in the digital media landscape. The context of this major alteration of ontological, axiological, and political dimensions is the increasing accessibility of the internet, the popularization of smartphones, and hyper-connectivity, which promotes this change. It is not a simple effect caused by human agency, but rather an effect of the alternative assemblage between human corporeality and non-human materiality to execute the disconnection from the hegemonic pattern of sexist assemblage between person, social media, and digital territories. The distinction between natural and artificial and human and non-human is abolished by the feminist net-activism that facilitates social innovations.

Since 2015, the year when the South Korean website Megalia—a website that combines rage and humor and, through its meteoric success, spurred the emergence of the feminist multitude—was created, the dynamics of South Korean feminism have relied on networked connectivity. This digital connectivity is not a dematerialized condition, but an assemblage of human corporeality, digital media technologies, cyber territoriality, and digital infrastructure. Feminist net-activism is characterized by the material processes of digital connectivity, and is therefore the product of an actor-network. This type of actor-network problematizes the hegemonic network patterns that reinforce rape culture. According to “Actor-Network Theory” (Latour, 2005), this misogynistic culture can be defined as a relational effect of a heterogeneous association of humans and non-humans. “Mediated misogyny” (Vickery & Everbach, 2018), which is gaining traction in cyberspace, is a solid network pattern made up of (1) human actors imbued with social prejudices who are producing user-generated content and (2) non-human actors that serve as the digital infrastructure for circulating pornographic and sexist messages, images, data, and bits.

Four Stages of Translation: The Creation of the Feminist Actor-Network

The feminist “multitude” (Hardt & Negri, 2005), a collective of bodies, disrupts the hegemonic network of conservative and male chauvinist associations by injecting conflict and instability into this network. The process of creating a new type of actor-network involves “translation” (Callon, 1986). According to Callon, translation includes four stages: problematization, interessement, enrollment, and mobilization.

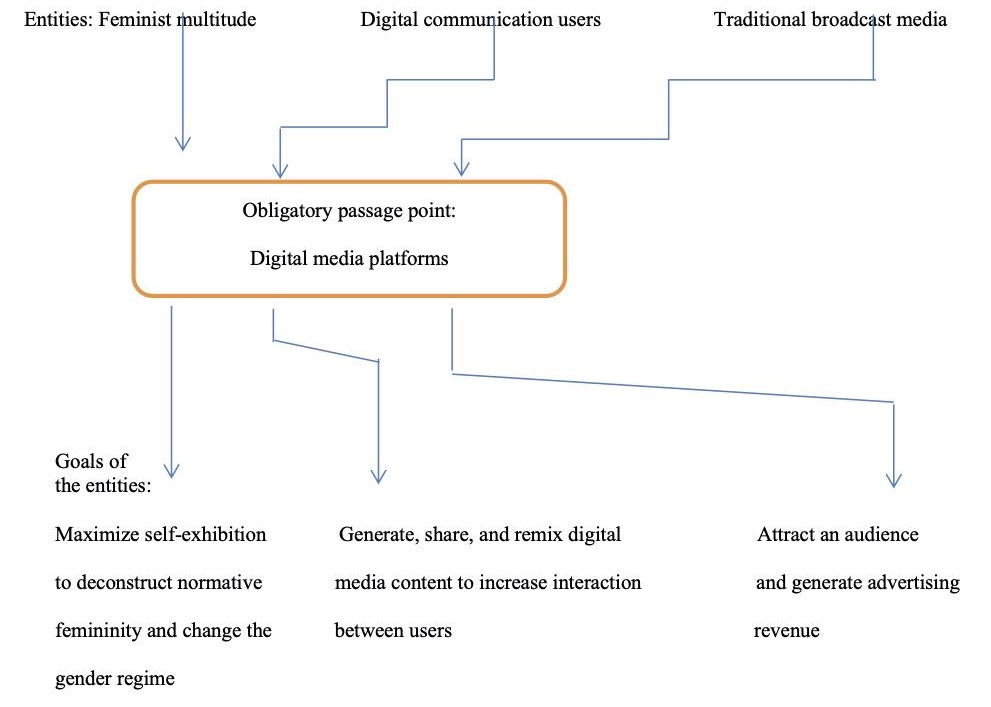

I will illustrate these four stages of translation in the case of the #EscapeTheCorset_Exhibition movement. The first stage is problematization, which involves redefining human and non-human actors and establishing obligatory passage points through which all actors must cross. In the #EscapeTheCorset_Exhibition movement, the South Korean feminist multitude identified three entities: the feminist multitude, digital communication users, and traditional broadcast media:

- a) The feminist multitude includes those who try to create new material realities of women’s bodies liberated from oppressive devices, such as make-up products, diet products, plastic surgery, and high-heeled shoes, which confine women to the existing standard of beauty.

- b) Digital communication users are those who gather and reframe media content and interact with other users.

- c) Traditional broadcast media are devices and institutions that produce news and information—especially those that do so through digital media.

These three actors or entities must pass through the obligatory passage point of digital platforms. Digital media platforms are not passive substances devoid of agency onto which digital users inscribe their intention. They are rather material assemblages through which the feminist multitude, digital communication users, and traditional broadcast media constitute each other and form an alliance. The obligatory passage point of this digital media environment guarantees accessibility, visibility, and dissemination, and connects each entity to its goals (Figure 1).

The feminist multitude uses the obligatory passage point to maximize their self-exhibition by sharing images of their rebellious flesh and indocile bodies to challenge the gender regime. Feminist digital activists aim to deconstruct normative and hegemonic femininity that supports the efficiency of the patriarchy. Digital communication users go through the obligatory passage point to generate, share, and remix digital media content to increase user interaction and enjoy interesting content. Traditional broadcast media use the obligatory passage point to attract more audience attention and thereby generate advertising revenue. Through digital media platforms, these three entities form an alliance that enables each party to meet their goals.

The second stage of translation is interessement, which is “the group of actions by which an entity attempts to impose and stabilize the identity of the other actors” (Callon, 1986, pp. 207–208). In the #EscapeTheCorset_Exhibition movement, the feminist multitude uses various devices to reinforce the alliance between the three entities mentioned above. These devices are deployed in digital media platforms. For example, the feminist multitude deploys transgressive “selfies”—such as images of women with no make-up, cut hair, or shaved heads—as an interessement device to attract the attention of digital communication users and produce more reactions and circulations of this hashtag activism. Further, the feminist multitude—in concert with digital communication users—produces data traffic and digital content within a hashtag movement as an interessement device to encourage traditional broadcast media to treat the movement as a social phenomenon. In this way, “[t]he interessement attempts to interrupt all potential competing associations and to construct a system of alliances” (Callon, 1986, p. 211). The goal of this stage is to consolidate a certain form of association—specifically, the form that the feminist multitude recommends and prefers—at the expense of other forms.

The third stage of translation is enrollment, which consists of defining and assigning roles to actors. In the #EscapeTheCorset_Exhibition movement, the role of the feminist multitude is to (1) make those feminist practices and perspectives that do not obey the existing standard of beauty visible and (2) to spread feminist political awareness to change the attitude of other digital users. The role of digital communication users is (1) to be persuaded by the feminist affect and perspective and (2) to participate in these embodied practices. The role of traditional broadcast media is to (1) provide news and information about the lookism-based social pressure that women experience, including the expansion of the cosmetics industry for preschool girls, and (2) to make this hashtag activism one of the most important social issues. In this stage, “the definition and distribution of roles are a result of multilateral negotiations during which the identity of the actors is determined and tested” (Callon, 1986, p. 214). This attempt at negotiation could fail, as other users are reluctant to participate in these embodied practices that contest the desirable and reproductive body endorsed by patrilineal society, and as backlash from anti-feminist groups using cyberbullying to humiliate feminist activists impedes the formation of the actor-network that the feminist multitude aspires to constitute. Using these interessement devices, the feminist multitude advocates an alternative type of actor-network.

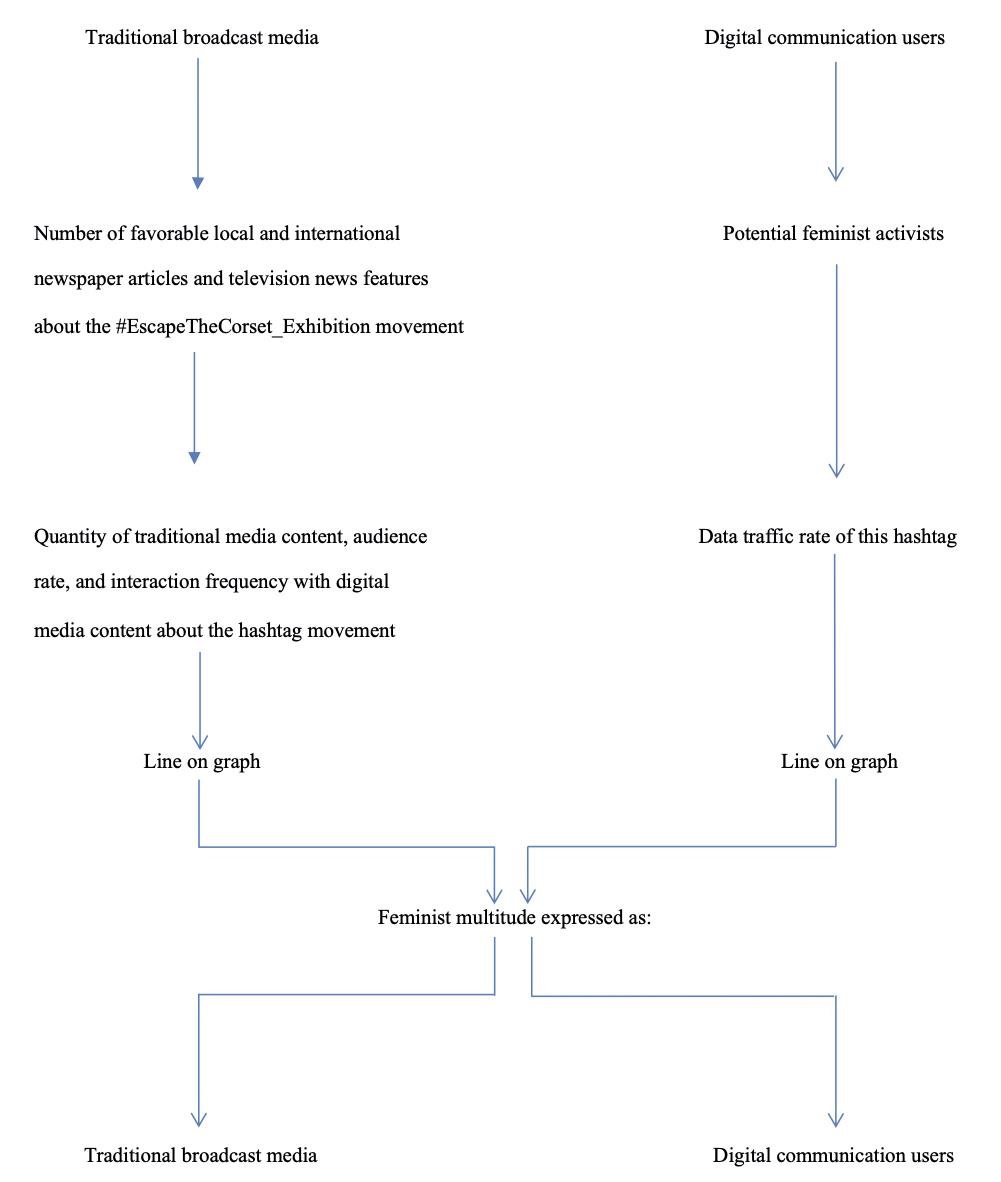

The last stage of translation is mobilization, which entails a process of representation and displacement. Having determined what these entities—digital communication users and traditional broadcast media—are and want, the feminist multitude transforms these entities into deliverables expressed as online engagement metrics (Figure 2). This enables the feminist multitude to subsume these entities, rearticulating them as alternate manifestations of itself. Thus, the feminist multitude is an influential actor that reassembles these two entities through the digital media landscape. This progressive mobilization, achieved through a series of negotiations and contestations of existing misogynistic networks, constitutes the alliance between the feminist multitude, digital communication users, and traditional broadcast media as a new type of feminist actor-network.

In the #EscapeTheCorset_Exhibition movement, the Korean feminist multitude transforms “me” to “we.” By promoting collaboration between traditional broadcast media and digital media, the Korean feminist multitude exposes the absurdity of beauty norms that results in the degrading of women’s bodies and minds. This experience, which can often be overlooked, now obtains significance and becomes a universal phenomenon that draws attention. The high visibility of a hashtag movement on social media becomes a social issue that traditional media deal with. The interaction between traditional media and new media is what bring turbulence to the media landscape.

By the end of these four stages of translation, the feminist actor-network has been constructed. We see then that feminist hashtag activism, such as the #EscapeTheCorset_Exhibition movement, is not just an effective use of digital artifacts by human actors, but also a material media practice carried out by a collective of humans and non-humans. In this way, feminist net-activism creates “new forms of more-than-human agential relations” (Mendes et al., 2019, p. 28).

Feminist Net-Activism as Axiological Intervention

Feminists as Digital Prosumers

Feminist activists use different participatory platforms, such as Twitter, YouTube, and Instagram, to interact, create, and produce feminist political issues, share feminist artistic images, and utilize feminist archives. “The shift from distribution to circulation” (Jenkins, Ford, & Green, 2018, p. 2) is what characterizes the digital media landscape. In the digital media environment, feminist net activists are digital content prosumers—that is, not just consumers, but producers of digital media content and hashtag movements. They are not “simply consumers of preconstructed messages but those who are shaping, sharing, reframing, and remixing media content in ways that might not have been previously imagined” (Jenkins et al., 2018, p. 2). Feminist net activists use easily disseminated media to renew the modalities of resistance and reshape the theoretical paradigm of feminism. As such, “[t]he technological is not only instrumental, but generative of new forms of intensity, sensation, and value” (Hillis, Paasonen, & Petit, 2015, p. 10).

New Meaning of Feminism for Millennial Feminists

Millennial-aged members of the South Korean feminist multitude are digital natives who are inseparable from their digital connectivity and digital visibility. Considering the entanglement between online and offline space, they are exposed to not only the sexual discrimination that persists in the institution and the family, but also to the cybersexism that is produced every second and spread continuously. Faced with this rigid social and cultural context, millennial feminists adopt feminism as a self-defense tactic and as a strategy for disrupting the patriarchal and misogynistic society.

The millennial feminist multitude defines feminism as a strategy of survival and resistance, and no longer as a Western and progressive theory that is difficult to understand and reserved for academic elites. This new feminist generation, which calls its members Hellfeminists, is trying to redefine the value of feminism by framing it as a daily and political practice intended to acquire rights, claim power, break the cartel of male homosociality, and cultivate ambition. Hellfeminists are feminists who “come from Hell,” who cannot step back in the face of the material conditions of women’s existence, and who dare to disclose the atrocity of women’s reality, which is often ignored by society. Hellfeminists are digital natives—making them different from the older generation of feminists—who define feminism as an ethical and moral discourse based on political correctness and critical distancing from power, and who recommend empathy and sacrifice for other social minorities. The feminist multitude no longer seeks to prove that it is politically correct, devoid of political ambition, and committed to a noble cause that involves no personal interest. Its members adopt a more belligerent and practical attitude and do not hesitate to fight to obtain their share, of which they have been long deprived by men. This profound change in the purpose and value of feminism constitutes an axiological upheaval that gives rise to a new meaning of feminism.

This paradigm shift comes from the fact that the feminist multitude exists in—and must constantly fight against—a hyper-connected society where misogyny and rape culture have become a popular, widespread game among men, reproduced every second on online platforms, on the street, at school, and at home. For example, since 2019, an atrocious digital sex crime called the “Nth room” has persisted on Telegram, wherein “women and young girls enslaved online, the youngest of which was identified as 11 years old, are coerced to perform sexual as well as unusually cruel acts and record them for the viewers’ sexual pleasure” (Vitalosova, 2020, para. 5). In this very hostile and rigid digital environment, many young women absorb feminism and actively practice it to transcend their fear of being targeted by men’s sexual and sexist attacks. The atrocious reality that reduces women to objects for sexual exploitation through the conjunction of misogyny and advanced digital technology precedes and always exceeds the academic theory of feminism. Therefore, digital media platforms present an arena for thought and discussion on feminist issues, including the effectiveness of the feminist movement’s strategies. Furthermore, the feminist multitude criticizes the gap between women’s reality and the theory that feminist scholars provide. In this sense, South Korean millennial feminists challenge not only sexism but also elitism and the age hierarchy that is specific to South Korean society. In this way, feminist net activists try to break patriarchal structures and change the very paradigm of feminism.

The feminist multitude also questions the value of beauty, which is considered to be an intrinsic and ultimate value of women. Where the body positivity movement taking place in the United States criticizes the monolithic criterion of beauty, asserting the range and diversity of beauty by affirming that all women, regardless of age, body shape, and skin color, are beautiful, the #EscapeTheCorset_Exhibition movement radically problematizes the axiological value of beauty itself, stating that we attribute too much significance to this trait. The feminist multitude scrutinizes the gendered dimension of this value, which is particularly assigned to women. Instead of idealizing and pursuing beauty, the feminist multitude emphasizes women’s ambition, resilience, will to power, and success—all of which are traditionally male values. This new feminist generation wants to break the norm of femininity. Instead of remaining confined in the place assigned by men and resigning themselves to the social imperative of beauty and docility, the feminist multitude dares to break the corset that stifles the bodies and minds of women. In so doing, the feminist multitude endeavors to trace a new path of adventure and challenge. A woman free of the corset renounces the status of “doll,” well adored by men, to explore a new field of value that allows her to become an indomitable woman who changes the world.

The feminist multitude uses different digital platforms, successively and simultaneously, to create new meanings and values. On Twitter and Instagram, feminist net activists lead the hashtag movement #LifeOfWoman_Refusing_Marriage (#비혼여성의_삶 in Korean) to promote alternative life trajectories for women who do not want to join the patriarchal regime or submit to the phallic economy of desire. This exhibition of the lives of women who refuse marriage aims to criticize the overvaluation of married life, which monopolizes the “default mode” of a woman’s life. This hashtag movement consists of sharing advice for maintaining psychological-somatic health, which is the basic condition of not being overwhelmed by the culturally induced despair and self-hatred designed to make women dependent on men. Instead of flaunting a well made-up face and slender figure, the feminist multitude wants women to display and take pride in their diligence, studiousness, ambition, and intellectual brilliance—qualities that are not seen as strictly feminine. This hashtag movement on Instagram and Twitter aims to counter the disciplinary power that produces docile and harmless female bodies, while the cross-regional project led by the feminist YouTube channel 하말넘많 heavytalker1 aims to guarantee the visibility of the collective life of women refusing marriage. Demonstrating the collective activities of women who refuse marriage on YouTube encourages “a deep sense of affective collectivity and feminist solidarity” (Mendes et al., 2019, p. 21) and counters the bio-power that encourages women to become reproductive bodies that guarantee patrilineality. In this way, feminist solidarity goes beyond the distinction between online and offline space.

South Korean women are “using participatory digital media as activist tolls to dialogue and network” (Mendes et al., 2019, p. 2). It is through this interaction between different forms of participatory culture that millennial feminists reconfigure the individual and collective dimensions of women’s lives and “explore affective and material changes in the lives of girls and women” (Mendes et al., 2019, p. 23). The feminist multitude wants to create a new life cycle for women that no longer follows the path of wives and mothers, and feminist net activists are attempting to develop new civil society politics for those who live without a man—either alone or together with other women—so that they can acquire the same rights in matters of housing, medical services, and taxes as married couples.

Feminist Net-Activism as Political Participation

Creating Feminist Citizenship

In the Web 2.0 era, “the embodied and emotional intensities of practicing feminist activism” (Ahmed, 2017) give rise to a new modality of feminist citizenship that is an effect of the material-semiotic actor-network. These multi-layered networks are “material agents of politicization” (Fotopoulou, 2016, p. 17) that facilitate civic engagement. Through our entanglement with digital technologies, we are becoming feminist actors in fourth wave feminism, which is best understood as “networked feminism” (p. 49). The feminist multitude constitutes a new type of actor-network, which is “a site of non-hierarchical modes of connection” (Terranova, 2004). It stimulates political engagement from women who aspire to claim their fundamental rights from a society that does not respect women or acknowledge their rights. The feminist multitude carries out multiple direct actions to make feminist voices heard and change the structure of society, including organizing demonstrations in the street, leading hashtag movements on social networking sites, and actively participating in the presidential office’s (Blue House) petitions and online citizen petitions run by and addressed to the National Assembly. Networked feminism is “a form of contemporary political action that is characterized by complex connectivity and which operates at the intersections of online and offline” (Fotopoulou, 2016, p. 49). These political actions are not disembodied practices but embodied practices that produce an unprecedented amount of “networked affect” (Hillis et al., 2015). This intense affect is a material agency that creates resistance and enriches political actions and debates. As “[t]he individual who is plugged into digital devices is always more than human and more than an individual” (Mendes et al., 2019, p. 28), Hellfeminists, by virtue of their connection to digital participatory platforms, are not isolated individuals, but a “networked public” (Papacharissi, 2014). The feminist multitude, other digital communication users, traditional broadcast media, and digital platforms are all actors contributing to the dissemination of feminist ideas, problematizing the partiality of legal judgment, demanding the rectification of laws, and proposing a bill to address violence against women.

Feminist Political Digital Engagement in the Nth Room Case

One topic currently addressed by the new, networked feminist citizenship is the Nth room case—a particularly egregious digital sex crime involving the sexual enslavement of girls and women on Telegram chat rooms that has caused widespread indignation. According to one article, “[m]ore than 5 million signed petitions at [sic] an online platform run by the presidential office and shared hashtags, urging authorities to disclose all members of the chat rooms and punish them strongly [sic]” (Yonhap, 2020, para. 15). To demand the measures necessary to eradicate this ever-evolving digital sex crime, the group of anonymous women who launched project ReSET2—which enables Web users to report sexual exploitation on Telegram—is leading several online petitions addressed to the National Assembly and intended to influence the legislative branch. This political action, effected through digital participatory platforms, has helped to change public opinion, which was initially rather indifferent to this problem. Consequently, “[t]he group is now calling for heavier punishments for the possession of digital material documenting violent sexual cases, as well as the distribution of that material” (Seo, 2020, para. 31). In one month, this group of anonymous feminists obtained, via an online platform, more than one hundred thousand petitions demanding the preparation of a bill that (1) severely condemns this crime against women, and (2) establishes a system of international cooperation against digital sex crimes.

The feminist multitude also leads the hashtag movements #stop_nthroom, #nthroom_case, #nthroom_stop, #nthroomcrim_out, #nthroom_crime, #stand_againist_nthroom, and #nthroom_boycottelegram on Twitter and Instagram to attract the attention of people around the world and inform international and foreign newspapers of the severity of this digital sex crime. These hashtag movements solicit people’s participation in the deletion of implicated Telegram accounts and request Telegram’s cooperation in addressing this digital sex crime. This net-activism shares the link where one can have access to online petitions run by and addressed to the presidential office (Blue House) to influence the executive, legislative, and judicial branches.

These digital practices are not limited to the simple act of circulating data that replaces “real” political engagement. Unlike Jodi Dean, who argues that “the expansion of the public’s capacity to circulate messages has too often been fetishized as an end in itself, often at the expense of real debate or actions” (Jenkins et al., 2018, p. 43), I assert that these net activist movements are trying to restructure the system itself—police, prosecution, and tribunal—which is made up mostly of males imbued with macho and conservative prejudices. In their work, Dean relegates these actions to “communicative capitalism” (Dean, 2005, 2009, 2010), arguing that “the constant circulation of media content coupled with the fantasy of participation and the ability to feel political through practices such as signing an online petition foreclose any real prospect for social change” (Mendes et al., 2019, p. 30). However, feminist digital engagement has demonstrably influenced policy and reshaped the perspectives and attitudes of many people in profound ways. In response to the net-activism surrounding the Nth room case, “[p]rosecutors have set up a special task force to investigate sexual exploitation and content distribution crimes involving minors on the Telegram messaging app” (“Prosecutors Set Up Task Force,” 2020, para. 1). In addition, most citizens now aspire to eradicate such violence against girls and women once and for all.

In South Korea, two systematic methods of blaming victims of sexual assault and imposing silence on them are to threaten them with defamation proceedings on the basis that what they claim is untrue, or the threat that they will be charged with and prosecuted for making a false accusation of rape. These two methods foster rape culture. Thanks to fourth wave feminism that contributes to raising awareness of the absurdity of these two provisions, the movement for the abolishment of the defamation provision has been supported by lawmakers and the feminist multitude. Furthermore, the feminist association that supports the #Metoo movement has started to draw up some manuals to protect the victim and to eradicate the systematic stigmatization of the victim’s reliability.

Furthermore, net activists are redefining justice from a feminist perspective by calling for an increase in the number of female police officers, female judges, and female prosecutors participating in this case, given the indifference of male judges, police, and prosecutors who deliver very light sentences for digital sex crimes. Net activists denounce this partiality, lack of sensitivity, and legal oversight that allow Nth room participants to escape justice and are attempting to correct this structural violence by demanding political representativeness for women in all social fields, and especially in the legislative, judicial, and executive sectors.

Feminist solidarity that promotes civic engagement and political action is no longer based on geographic proximity but on the intensity of digital connectivity. Even if women are dispersed across regions, they congregate around social problems concerning the life of women, forming an assemblage on digital platforms and constituting an actor-network that creates feminist citizenship. This actor-network that advocates feminist politics “reshuffles spatial metaphors” that are based on the distinction between “close and far, up and down, local and global, inside and outside” (Latour, 1996, p. 6). Although a female feminist might sit next to a male misogynist colleague in the workplace, she has no emotional or intellectual connection to him. Contrastingly, women do not hesitate to form feminist solidarity and lead with hashtag activism to support the girls and women who are victims of digital sex crimes, even when their faces and names remain unknown. In this net-activism, geographic distance is irrelevant. What prevails is the intensity of digital connections based on networked affect, which produces more digital content on feminist issues and more participation in political actions via digital platforms. Thus, “[f]eminists use networked media to stay connected and to engage new participation in their actions” (Fotopoulou, 2016, p. 40). Patriarchal society always works to oppose women to each other, as this hinders women’s solidarity, thereby preventing resistance to the unequal regime that guarantees male domination. However, feminist net-activism enables feminist solidarity across space and time, organizing direct actions and developing feminist politics to dismantle rape culture, which shapes both networked environments and offline spaces. Digital activist practices in the new media ecology materialize the agency of the feminist actor-network to eradicate violence against women and create feminist citizenship, profoundly subverting the dynamics of power.

Conclusion

This article characterized the digital media ecology as a dynamic, online–offline site of tensions and contradictions where millennial feminists and anti-feminists confront each other and multiply. Within this setting, a feminist collective of human and non-human actors develops and consolidates feminist citizenship while defying the hegemonic network of patriarchy. This actor-network transmits and affirms feminism as the “spirit of the century,” cultivating a networked affect that stimulates feminist net-activism and resistance to mediated misogyny and virulent sexism. I argued that these digital practices constitute a situated and embodied practice that is crucial for understanding fourth wave feminism, which is, in essence, networked feminism. The digital practices referred to within the context are not disembodied, but are the results of an entanglement between human corporeal agency and non-human material agency. These practices are inscribed in concrete social and political contexts and foster a situated perspective that admits a form of embodied subjectivity, not a non-situated and abstract one. The concrete situatedness is a source of the feminist multitude’s power to enhance the intensity of their activism. The unpredictable dynamics of feminist net-activism—expressed through these ontological, axiological, and political dimensions—reshape the theoretical and practical paradigm of feminism and accelerate the dismantling of oppressive social structures.

In the ontological sphere, feminist digital practices do not simply involve the use of digital devices; they constitute embodied practices of resistance involving the material agencies of human corporeality, digital territoriality, and digital infrastructure. Through net engagements like the #EscapeTheCorset_Exhibition movement, feminist net activists actively construct a new type of actor-network that destabilizes prevailing sexist networks by weaving an agential relationship with non-human actors, such as smartphones, mobile apps, digital media platforms, and data streams. The feminist multitude and digital technologies are literally entangled as well as implicated within this hyper-connected society, and feminist net-activism entails an ontological turn, wherein action arises from a collective of human and non-human actors.

In the axiological sphere, the feminist multitude challenges existing orders of value and meaning, redefining feminism as a strategy of survival and resistance to everyday life, which is charged with misogyny and rape culture. The millennial feminist—as a digital content prosumer—opens the field of discussion to propose new themes for the feminist movement and redirect the objective of feminism toward obtaining fundamental rights and power. As the vanguard of fourth wave feminism, feminist net activists are not passive recipients of digital content; they are actors who reframe digital media content and intervene in the axiological field to reinvent the life cycle of women in ways that are not subjugated to the patriarchal regime. Through initiatives like #LifeOfWoman_Refusing_Marriage, women who are spread across all regions of South Korea remain solidarized, sharing multiple strategies for leading a healthy and ambitious life and advocating intellectual and emotional capacities in the face of loneliness and social exclusion.

In the political sphere, the feminist multitude carries out civic engagements via online citizen petitions to propose bills to the National Assembly and to demand an appropriate response from the executive branch. These corporeal and political actions arise from an assemblage of human and non-human actors—a feminist actor-network that enables the emergence and proliferation of political initiatives on digital participatory platforms by enabling cooperation and participation. Considering the Nth room case, the feminist multitude carries out hashtag activism to inform the public, attract attention, and circulate online petitions to change the gender composition of the government. These networked, embodied practices generate public indignation as a networked affect that gives rise to feminist citizenship and triggers political engagement. By strengthening the material agency of women and non-human actors, these actions contribute to the restructuring of society.

Through this analysis, I used the Actor-Network Theory to articulate a practice-based model of fourth wave feminism that departs from previous ideology-based feminisms. In so doing, I hope to have elucidated fourth wave feminism in both the global and South Korean contexts. Future research should examine the potential of feminist digital practices further, using the lenses of object-oriented ontology (Harman, 2018) and material feminism (Alaimo & Hekman, 2008) to identify implications and trajectories that we have not examined in this article.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported by the KU Research Professor Program of Konkuk University, the Republic of Korea’s Ministry of Education, and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2017S1A5B8057457).

References

- Ahmed, S. (2017). Living a feminist life. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Alaimo, S., & Hekman, S. (2008). Material feminisms. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Baumgardner, J. (2011). F’em!: Goo, gaga, and some thoughts on balls. Berkeley, CA: Seal Press.

-

Bijker, W. E. (1993). Do not despair: There is life after constructivism. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 18(1), 113–138.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/016224399301800107]

-

Callon, M. (1986). Some elements of a sociology of translation: Domestication of the scallops and the fishermen of St Brieuc Bay. In J. Law (Ed.), Power, action, and belief: A new sociology of knowledge (pp. 196–233). London, UK: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.1984.tb00113.x]

- Cochrane, K. (2013). All the rebel women: The rise of the fourth wave of feminism [Kindle edition]. London, UK: Simon & Schuster.

-

Dean, J. (2005). Communicative capitalism: Circulation and the foreclosure of politics. Cultural Politics, 1(1), 51–74.

[https://doi.org/10.2752/174321905778054845]

-

Dean, J. (2009). Democracy and other neoliberal fantasies: Communicative capitalism and left politics. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822390923]

- Dean, J. (2010). Blog theory: Feedback and capture in the circuits of drive. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

-

Evans, E. (2015). The politics of third wave feminisms: Neoliberalism, intersectionality, and the state in Britain and the US. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

[https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137295279]

-

Fotopoulou, A. (2016). Feminist activism and digital networks: Between empowerment and vulnerability. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

[https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-50471-5]

-

Gill, R. (2007). Post-feminist media culture: Elements of a sensibility. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 10(2), 147–166.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549407075898]

- Hansen, M. B. N. (2006). Bodies in code: Interfaces with digital media. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Hardt, M., & Negri, A. (2005). Multitude: War and democracy in the age of empire. London, UK: Penguin.

-

Harman, G. (2018). Object-oriented ontology: A new theory of everything. London, UK: Pelican Books.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.997]

-

Hillis, K., Paasonen, S., & Petit, M. (2015). Networked affect. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

[https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9715.001.0001]

-

Jane, E. A. (2014). “Your a ugly, whorish slut”: Understanding E-bile. Feminist Media Studies, 14(4), 531–546.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2012.741073]

-

Jane, E. A. (2016). Online misogyny and feminist digilantism. Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies, 30(3), 284–297.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2016.1166560]

- Jenkins, H., Ford, S., & Green, J. (2018). Spreadable media: Creating value and meaning in a networked culture. New York, NY: New York University Press.

- Latour, B. (1996). On actor-network theory: A few clarifications. Soziale Welt, 47(4), 369–381.

- Latour, B. (1999). Pandora’s hope: Essays on the reality of science studies. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social: An introduction to Actor-Network Theory. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- McRobbie, A. (2008). The aftermath of feminism: Gender, culture, and social change. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

-

Mendes, K. (2011). “The lady is a closet feminist!” Discourses of backlash and postfeminism in British and American newspapers. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 14(6), 549–565.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877911405754]

-

Mendes, K., Ringrose, J., & Keller, J. (2019). Digital feminist activism: Girls and women fight back against rape culture. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190697846.001.0001]

-

Munro, E. (2013). Feminism: A fourth wave? Political Insight, 4(2), 22–25.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-9066.12021]

- Nouraie-Simone, F. (2005). Wings of freedom: Iranian women, identity, and cyberspace. In F. Nouraie-Simone (Ed.), On shifting ground: Muslim women in the global era (pp. 124–144). New York, NY: The Feminist Press.

-

Papacharissi, Z. (2014). Affective publics: Sentiment, technology, and politics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199999736.001.0001]

- Penny, L. (2013). Cybersexism: Sex, gender, and power on the internet [Kindle edition]. London, UK: Bloomsbury.

- Poland, B. (2014). Cybersexism in the 21st century. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Prosecutors set up task force to investigate sexual exploitation crimes on Telegram. (2020, March 25). KBS World Radio. Retrieved March 25, 2020, from https://world.kbs.co.kr/service/news_view.htm?lang=e&Seq_Code=152295

-

Ringrose, J. (2013). Post-feminist education? Girls and the sexual politics of schooling. London, UK: Routledge.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203106822]

- Scharff, C. (2012). Repudiating feminism: Young women in a neoliberal world. Farnham, UK: Ashgate.

- Seo, Y. (2020, March 28). Dozens of young women in South Korea were allegedly forced into sexual slavery on an encrypted messaging app. CNN. Retrieved March 28, 2020, from https://edition.cnn.com/2020/03/27/asia/south-korea-telegram-sex-rooms-intl-hnk/index.html

- Terranova, T. (2004). Network culture: Politics for the information age. London, UK: Pluto Press.

- Toffler, A. (1980). The third wave: The classic study of tomorrow. New York, NY: Bantam.

-

Vickery, J. R., & Everbach, T. (2018). Mediating misogyny: Gender, technology, and harassment. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-72917-6]

- Vitalosova, D. (2020, February 6). South Korean “Nth Room” chats are keeping girls in sexual slavery: And no one is doing anything about it. 4W. Retrieved March 23, 2020, from https://4w.pub/south-korean-nth-room-chats-are-keeping-girls-in-sexual-slavery, /

- Yonhap. (2020, March 25). Telegram sex offender’s case sent to prosecution. The Korea Herald. Retrieved March 25, 2020, from http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20200325000174

Biographical Notes: Ji-Yeong Yun is an assistant professor at the Institute of Body and Culture at Konkuk University, South Korea. She received her Ph.D. from University of Paris I, France. Her research interests include feminist philosophy, new materialist feminism, and Anthropocene feminism.