ICT Literacy for Marginalized Girls and Women’s Empowerment

Abstract

The gender digital divide still exists. Women and girls, particularly in developing countries such as the Philippines, are faced with the gender-based-digital exclusion that hindered them from utilizing ICTs for economic and social development. It is important to educate women and girls in ICT skills despite their financial and social status if sustainable development goals are to be achieved. This study is concerned with the assessment of the ICT literacy training of marginalized girls and women. The main objective of the study is to evaluate the outcome with regard to the individual empowerment of women and girls. This descriptive case study investigates the contribution of ICT to development from the perspective of the individual empowerment of women participants in ICT literacy training. The population of interest consisted of disadvantaged or marginalized women in Iligan City, Philippines. A convenience judgmental sampling method was used to identify participants for the training. The validity of the questionnaire used was verified by panel experts, and interviews were also used as a complementary instrument. Out of 90 respondents, only 40 women were selected as participants for the first phase of the ICT literacy training. Moreover, the goal was to evaluate the outcome of the training regarding individual empowerment from the perspective of the women participants. The results of the study implied that the training was effective in realizing its objectives—to empower marginalized women and girls through capacity building. This initiative demonstrated responsiveness to the challenges posed by the gender digital divide, which had been identified through data gathering.

Keywords:

gender digital divide, ICT women empowerment, outcome evaluation, ICT literacyIntroduction

ICT success stories in developing countries show that ICT can impact women in remote regions and can transform their lives through information and job creation, driving women to empowerment (Huyer & Sikoska, 2003; Wamala, 2012). However, not all individuals have equal opportunities to access and benefit from technology, which, in developing countries such as the Philippines, contributes to the so-called “digital divide.” The affluent and educated are still more likely to have good access to digital services than others (Hilbert, 2011). This was asserted in the study by Roberts and Hernandez (2019), which showed that digital inequalities will remain regardless of increasing connectivity; the most marginalized communities are hardly connected and cannot participate in digital citizenship programs. The “digital divide” has been inevitably tied with a lack of skills, access to ICTs, and inequality of access and process (Kularski & Moller, 2012; Van Dijk & Hacker, 2003), and often exacerbates social inequalities (Antonio & Tuffley, 2014) by which women are more affected.

This notion of the gender digital divide is often perceived as the reason that the power of women is not increasing. This leads to a recognition that ICT as a diverse aspect comprises some circumstances that hinder women in communicating through and accessing digital information (Olatokun, 2007). It could be that women perceive themselves as incapable of understanding or using ICTs, others may not have the privilege of accessing ICT materials or have opportunities to engage with ICT resources, and lastly, it may be related to the social inclusion perspective (O’Neil et al., 2014).

In recent years, the need to empower women through literacy has been receiving attention. Literacy is a “human right,” an element in dealing with equity (Eldred, 2013), and ICT literacy is thought of as a vital competency for fully taking part in a knowledge-driven economy and society (Australian Council for Educational Research, 2016). It can be delineated as “using digital technology, communications tools, and/or networks to access, manage, integrate, evaluate, and create information in order to function in a knowledge society” (International ICT Literacy Panel, 2002, p. 2). Moreover, ICTs can be an effective instrument to empower women and a catalyst for economic growth, especially in underdeveloped areas (Cummings & O’Neil, 2015). Some authors have asserted that access to ICTs will ensure social inclusion and economic transformations for marginalized groups (Nemer, 2015; Njoki & Wabwoba, 2015; Roberts & Hernandez, 2019). Moreover, literacy skills “can act as a catalyst which can both precipitate progress across the goals and multiply their benefits in mutually reinforcing ways” (Wetheridge, 2016, p. 1). Therefore, literacy matters, because we understand that training and literacy skills improve the likelihood of acquiring work and completely engaging in society.

Empowerment is a multidimensional notion that brought about the personal and social development of women (or men): Having the power to exercise choice and resolve external issues, control their personal lives, and have critical consciousness (Eyben, 2011; Rowlands, 1997). The link between literacy learning, empowerment of women, and the achievement of greater equality has been demonstrated in international organizations. For example, literacy was recognized as the central component of the right to education in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights since it promotes the promotion of other human rights and the ideals of equality for human development (UIL, 2013; UNESCO, 2006a, 2016). Therefore, literacy has the potential to boost the ability of people to act in the pursuit of independence and increase their ability, and plays a crucial role in empowering and transforming their lives (Dutt, 2017).

In addition, women are capable of improving and growing in various facets of their life, including psychological, political, social, and economic (Kenkarasseril, 2013; Luttrell et al., 2009; Rowlands, 1997). The study by Cummings and O’Neil (2015) showed that ICT’s impact on providing women’s basic inputs was to enhance their ability for better decision-making, learning opportunities, and technical or practical skills. Clearly, ICTs have a vital role in women’s progress and contribute to empowerment, providing opportunities such as in business, skills training, and information on global issues, to mention some. It also has the capacity to empower marginalized communities (Zikmund, 2000).

Studies have presented the contribution of ICT as a tool to overcome inequities for women, to leverage status, and for empowerment (Beena & Mathur, 2012; Khan & Ghadially, 2010; O’Neil et al., 2014; Rathi & Nyogi, 2015; Wagner et al., 2005; Zikmund, 2000). One example was the study by Beena and Mathur (2012), in which 94% of 200 women who attended the ICT training in Jaipur District in India said that it provided “technological empowerment” because the acquired skills provided them with “greater confidence and competence.” Researchers investigating the impact of ICT training programs generally conclude that trainees are empowered as a result. However, the studies presented are from countries like India and Bangladesh, and there is a lack of research data with regard to ICT and women empowerment in the Philippine context.

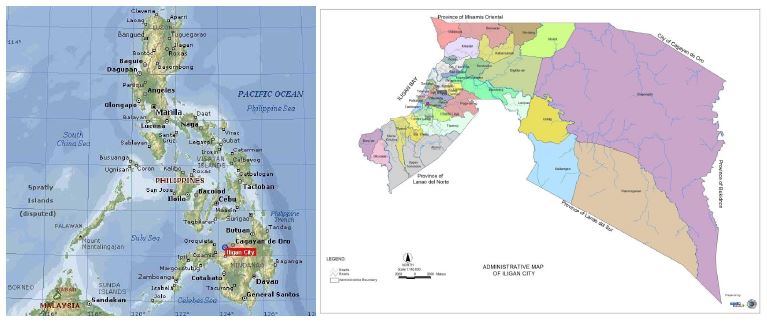

There are 7,017 islands in the Philippines, 8 regions of 82 provinces, 135 cities and 1493 municipalities, and there are great inequalities from region to region. There is very little development taking place in the provincial regions, especially those outside the Luzon area, and most of the economic potential is concentrated in highly urbanized regions in Luzon and Visayas. In contrast to the Luzon region, Mindanao has lower revenue groups in the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) and Regions 9–12. Mindanao has historically lagged behind Luzon and Visayas in terms of infrastructure growth and other areas, including ICT. It can be argued that Mindanao contains the largest number of marginal communities, especially in provinces like Lanao del Sur and Lanao Del Norte. Apparent gaps exist between regions primarily because of resources, which include not only tangible infrastructure but also information capital (Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, 2017).

In order to provide internal criteria for technologically literate workers, there is a need to improve ICT skills in all regions of the Philippines. Exposing learners to technology produces potential workers who can later be expected to use ICT to maximize efficiency, minimize costs, and enhance outcomes (Rodrigo, 2001). ICT literacy training has been initiated by the government and non-government organizations, but mostly for teachers and limited to specific cities only (Bitanga, 2013; DICT, 2019, 2020; Echeminada, 2013; Good Things Foundation, 2016; Knowledge Community, 2020) neglecting marginalized groups and poorer communities. These efforts may be welcome, but there is more work to be done to address the country’s digital divide. As part of the community extension, there is a way that academic institutions can also contribute by offering capacity building to their nearest community. The case study conducted here is located geographically within the province of Lanao del Norte. Iligan City belongs to a first-class district with 44 barangays and has a number of marginal communities.

In an increasingly digital literate society, the effect for people who lack basic digital skills is on employability, community, and social participation, and they are increasingly excluded as the government and increasing numbers of companies digitize their services (Good Things Foundation, 2016; Dalberg Global Development Advisors, 2017). ICT has a vital role in the development of the Philippines, but not everyone has access to or is given equal opportunity to receive ICT training and develop skills. Numerous resource-poor communities in Mindanao, in particular, do not have opportunities for training, thereby contributing to the digital divide and to the disparities in ICT access, usage, skills, support, and involvement. There is a need for marginalized groups of people, especially women in regions of Mindanao region like Iligan City, to assimilate ICT skills and capabilities to enable their empowerment and provide them with the knowledge and skills needed in the post-digital-era world. These tools are expected to reshape education, social relations, recreation, work, and other relevant transactions. Knowing the role women play in families and communities means that benefits are likely to be sustainable across generations.

Given that ICT skills are vital for sustainable development, the goal for this project is to create an ongoing opportunity for women and girls (who do not have the opportunity to learn ICT skills) through ICT literacy training that will act as a catalyst to empower them and somehow change their lives for the better. In addition, a Gender Digital Divide still exists in the Philippines, but it is difficult to provide factual evidence due to a lack of research. It is in this context that this study intends to contribute to ICT4D (Information and Communications Technologies for Development). As mentioned above, empowering marginalized women and girls through ICT training, especially in the Philippines’ resource-poor community, is vital. The objective of the study is to evaluate the ICT training for marginalized women and girls from the perspective of individual empowerment in Iligan City, Philippines.

In light of the value of ICT skills in reducing the gender digital divide and promoting sustainable development, the research question is as follows: “What are the outcomes of ICT training for marginalized girls and women in terms of their individual empowerment?”

Literature Review

Gender Digital Divide

The State recognizes the role of women in nation-building, and shall ensure the fundamental equality before the law of women and men - pursuant to Section 14, Article II of the Constitution, Executive order no. 273

The era of the digital revolution is changing how society lives, works, and engages. ICTs give immense possibilities in ways we could never imagine. There are boundless opportunities because accessing information is within our reach, but beyond this there is also a challenge to equality with regard to who it is that actually benefits and whose voice is the one heard. Accordingly, “the digital divide is composed of a skill gap and a gap of physical access to Information Technology (IT) and the two gaps often contribute to each other in circular causation. Without access to technology, it is difficult to develop technical skills and it is redundant to have access to technology without first having the skill to utilize it” (Kularski & Moller, 2012, p. 5).

According to Keniston and Kumar (2003, p. 3–11), there are four digital divides that are interrelated. The first divide exists within every nation, industrialized or developing, “between those who are rich, educated, and powerful, and those who are not” (p. 3). The second, frequently overlooked, is the linguistic and cultural gap, especially between those who speak English or another Western language and those who do not (p. 5). The third digital divide is that “exacerbated by disparities in access to information technology between rich and poor nations” (p. 11). The final one is that of “the emergent intra-national phenomenon of the ‘digerati,’ an affluent elite characterized by skills appropriate to information-based industries and technologies, by growing affluence and influence unrelated to the traditional sources of elite status, and by obsessive focus, especially among young people, on cutting edge technologies, disregard for convention and authority, and indifference to the values of traditional hierarchies” (p. 11).

Moreover, the internet is acknowledged as a major factor in equal opportunity and economic advancement in that it has flattened the world (Open Textbooks for Hongkong, 2015). The prevalence of the internet has changed and revolutionized the design of both public and private services. The rapid changes in ICT have created considerable impediments for people in developing countries (West, 2015). Factors that create such difficulties in accessing the internet and highlight the prevailing gaps between those who are connected and those who are not include “poverty; high device, data, and telecommunications charges; infrastructure barriers; digital literacy challenges; and policy and operational barriers” (West, 2015, p. 2). The negative consequences of the digital divide are primarily addressed in relation to well-being, social capital, social inclusion, and social support (Friemel, 2014). According to the 2018 ITU report (ITU, 2018), lack of ICT skills is a critical hindrance in utilizing ICTs, especially in developing countries and LDCs, and highlights a severe constraint on potential development.

Technology “mirrors the societies that create it, and access to (and effective use of) technologies is affected by intersecting spectrums of exclusion including gender, ethnicity, age, social class, geography, and disability” (O’Donnell & Sweetman, 2018, p. 217). Hence, Gurumurthy’s (2004, p. 1) argument that “these technologies are not gender neutral” is true since digital society is overwhelmingly male-dominated. The concept of a “digital gender divide” is commonly associated with types of gender disparities in accessing the capabilities of and effectively utilizing ICTs within and between countries, regions, sectors, and socio-economic groups (UN Women, 2005).

Further, women generally have a lower chance than men to access information and acquire new technologies, especially in South Asia, where women are 70% less likely than men to access the internet and only 26% are less likely to own a mobile device (GSMA, 2018). This gender digital disparity is an important issue, as today’s economy is driven by information and it will be the most marginalized groups in poor urban and rural areas who will be the last to utilize and to take advantage of ICTs, creating an obstacle in their decision-making process and limiting their community impact. Therefore, having the chance to participate and be involved in digital information to acquire knowledge and skills is vital for their human and democratic rights and for their livelihoods (Antonio & Tuffley, 2014).

The digital divide still exists in the Philippines. In 2018, it was estimated that about 45.3% of individuals in developing countries used the internet. For the Philippines, 60.05% of the population is classified as internet users (ITU, 2018), ranked 101th out of the 175 countries according to the ICT Development Index (IDI) in the 2017 survey (ITU, 2019). Even basic internet connectivity is a problem since the country is an archipelago of 7,107 islands. Although there is highly concentrated connectivity in urban areas, a large number of poor, rural areas are underserved. According to the Asia Foundation, as reported by Pablo (2018), “outdated laws and policies have blocked the deployment of technologies that could bring the Philippines fully into the digital age” (p. 1). To overcome these shortcomings, the government implemented the “National Broadband Plan that envisions a resilient, comfortable and vibrant life for all, enabled by open, pervasive, inclusive, affordable, and trusted broadband internet access” (DICT, 2017, p. 4).

Capacity building measures and policy suggestions have been enacted to bridge the digital divide in the country. The biggest project so far was a government initiative called the “iSchools Project.” This was carried out simultaneously nationwide beginning in 2008 but was halted in 2013 (Bitanga, 2013; Itaas, 2011; Lorenzo & Lorenzo, 2013; Manaog, 2011). The goal of the project was to “bridge the digital divide among public high school teachers and students by providing ICT literacy through access to digital applications in education. The component of the project includes the provision of ICT equipment, capability building and strengthened local support” (Lorenzo & Lorenzo, 2013, p. 190). Although this project was successful, it was conducted for the academic community only and not for marginalized communities such as out-of-school women and girls.

Moreover, the Foundation for Media Alternatives (FMA) reported on the digital gender gap in the country: Out of 10 points (the overall score) in the “digital gender report card measures,” online safety scored 7 points, affordability of internet scored 6 points, digital skills and education scored 5, while relevant content services and women empowerment scored only 4 points. This was in reference to the 14 indicators clustered into 5 categories: “Internet access and women’s empowerment, relevant content and services, online safety, affordability, and digital skills and education.” Acting upon this result, a five-point action plan was identified: “integrating gender into Philippines’ national ICT plan; improving internet affordability and speed; implementing inclusive digital literacy programs; conducting gender audits of government agency websites; and putting an end to online gender-based violence” (Foundation for Media Alternatives, 2017, p. 1).

ICT has indeed proven to be a turning point in the twenty-first century, all the way from a knowledge-based economy to service provision and how we access information. As such, aside from reliable ICT infrastructure and concrete policies, an ICT-competent workforce is also vital to keep pace with the digital economy.

ICT Literacy and Women Empowerment

Education is an inalienable human right. It is also unique in that it empowers the individual to exercise other civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, attaining a life of dignity, while ensuring a brighter future for all, free from want and from fear. (UNESCO, 2006b)

Empowerment means “any process that enables autonomy, self-direction, self-confidence, [and] self-worth” (Narayan, 2005, p. 1) or as defined by Bystydzienski (1992), “a process by which oppressed persons gain some control over their lives by taking part with others in the development of activities and structures that allow people increased involvement in matters which affect them directly” (p. 3).

The United Nations recognized the all-pervasive nature of gender inequality and created the standalone Goal 5 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (as depicted in Figure 1) targeting “gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls” with its commitment to “leaving no one behind.” This specifically addresses the empowerment of women through ICTs and by mainstreaming gender equality across the SDGs on the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The target specific actions include: “5.b Enhance the use of enabling technology, in particular information and communications technology, to promote the empowerment of women; and 5.c Adopt and strengthen sound policies and enforceable legislation for the promotion of gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls at all levels ” (ADB & UN Women, 2018, p. 27). This provides remarkable opportunities to change the lives of women and girls and the improvements generated will lead to sustainability.

ICTs are an important instrument for gender empowerment and where other countries are already ahead in using ICT to their benefit, developing countries like the Philippines are still struggling to make effective use of it.

Studies have presented the contributions of ICT as a tool for women to overcome inequities, as a tool to leverage status, and as a tool for empowerment (Beena & Mathur, 2012; Khan & Ghadially, 2010; O’Neil et al., 2014; Paul & Thompson, 2018; Rathi & Nyogi, 2015; Wagner et al., 2005; Zikmund, 2000). Successful case studies have pointed out that ICT is a probable instrument in women empowerment, enriching their knowledge and skills. The study by Laizu et al. (2010) presented women’s empowerment in terms of perceptual change in rural villages in Bangladesh after ICT intervention. They used mixed-methods through a structured questionnaire and made a comparison between who used and did not use ICT in terms of women’s perception from two different villages where ICT projects were introduced. The results indicated more positive perceptions by women who used ICT. Another example was the study of Beena and Mathur (2012), whose results show (as mentioned earlier) that 94% of 200 women who attended the ICT training of the Jaipur District, India, said that it provided technological empowerment because the acquired skills gave them greater confidence and competence.

The project conducted by the World Wide Web Foundation (WWWF) (2014) in 10 countries provided evidence-based data on women empowerment and ICT issues to “promote the commitment and incorporation of action plans on women’s rights in ICT decision and policy-making spheres” (p. 4). This was carried out given the dearth of pertinent data regarding this matter. As Hafkin (2002) argues, when women are left out in ICT data, it means they are also ignored in data and policies. The project conducted focus group discussions and household surveys in ten countries (Kenya, Uganda, Mozambique, Nigeria, Cameroon, Egypt, Colombia, India, the Philippines and Indonesia). The WWWF claimed that web-enabled ICTs have the capacity to lessen certain constraints experienced by women, including “illiteracy, poverty, time scarcity, lack of mobility, cultural and religious taboos, and constraints on voice (particularly public voice) (p. 19).” They studied what they identified as the “seven key factors of web ICT access and use” in the context of women empowerment:

- i) Individual agency, self-esteem, self-expression (safety);

- ii) Social interaction (peer interaction, networking);

- iii) Public institutional participation

- iv) Access to and use of informational resources

- v) Access to communicative platforms

- vi) Access to associational/collective action spaces

- vii) Access to economic opportunity (World Wide Web Foundation, 2014, p. 12).

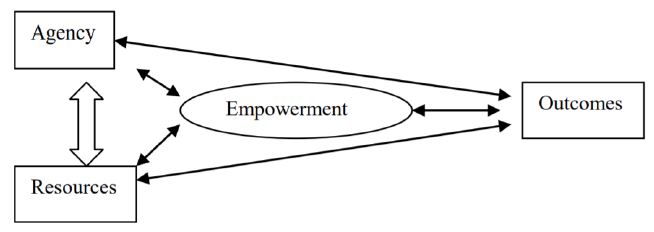

A conceptual framework for empowerment was suggested by Laizu et al. (2010), as shown in Figure 2. It illustrates the relationship between the three components of empowerment, “resources, agency, and outcomes (results associated with empowerment)” (p. 220). The process of empowerment is controlled by two factors: the Agency —ability to formulate choices; and the Resources —conditions for empowerment.

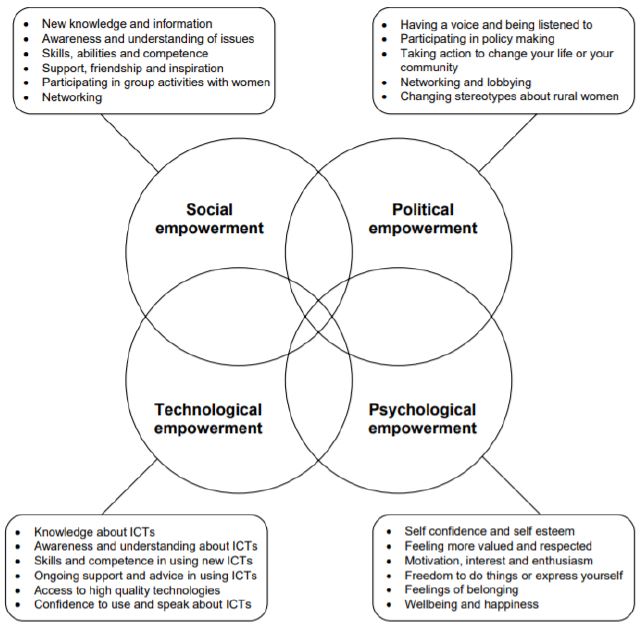

Moreover, the framework for empowerment proposed by Lennie (2001) includes technological empowerment as well as social, political, and psychological empowerment, forming four interrelated dimensions (shown in Figure 3). This was delineated in Lennie et al.’s Outcomes of the Learners Project (Lennie et al., 2004). They argued that social empowerment includes key elements of social capital (Woolcock & Narayan, 2000). It is required to enable effective participation in community action and decision-making and other processes that can lead to political empowerment (Friedmann, 1992). Psychological empowerment can result from successful action related to the community or to politics, as well as from “intersubjective work” (Friedmann, 1992, p. 33). Given the increasing use of the Internet and other C&IT in providing information, community consultation, and the networking of advocacy and lobby groups, technological empowerment is now becoming an important prerequisite to social and political empowerment (Lennie, 2001, 2002a, p. 27).

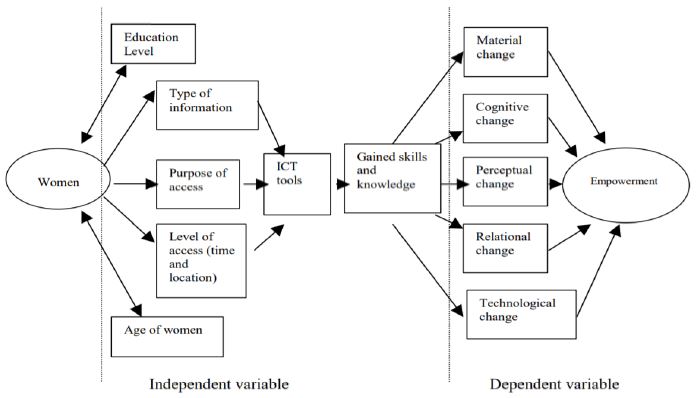

In addition, Laizu et al. (2010) proposed a model for assessing empowerment for ICT intervention (shown in Figure 4). As depicted, the independent variables vary for every woman, (e.g., education, age, motivation, other personal characteristics) and the dependent variables (material, relational, cognitive, perceptual and technological change) directly influence the independent variables.

Gigler (2004) argued that “improved access to information and ICT skills, similar to the enhancement of a person’s writing and reading skills, can enhance poor peoples’ capabilities to make strategic life choices and to achieve the lifestyle they value” (p. 1). According to Gigler, the indicator for individual empowerment has six dimensions (informational, psychological, social, economic, political, and cultural) that support individual human capability enhancement in various ways.

In this study, the focus is on the outcome assessment of ICT training for marginalized girls and women concerning individual empowerment.

Evaluation Framework

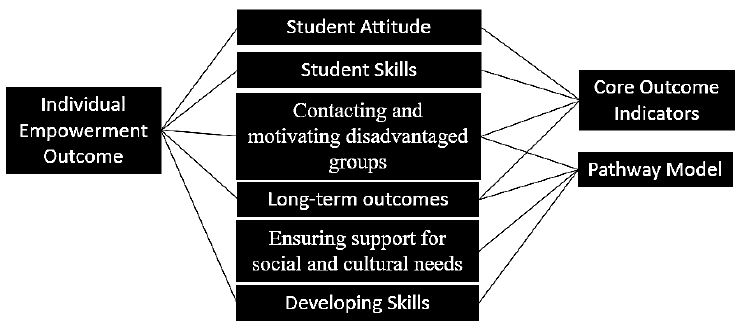

This study focuses on the empowerment of marginalized women and girls through ICT literacy training from the individual empowerment perspective. The evaluation framework in this study incorporates the proposed pathway model by O’Donnell et al.’s (2003) and the core indicators of computer training outcomes suggested by Wagner et al. (2005). Student attitudes and student skills are the main indicators of computer training success. In this study, the pathway model involves contacting and empowering marginalized communities, improving skills, and ensuring that social and cultural needs are supported.

The outcome of the program is individual empowerment, as shown in Figure 5. To assess individual empowerment, both the core indicators framework and the pathway model introduced above are used.

Methodology

This study aims to understand how ICT literacy training could empower marginalized women and girls in a resource-poor community in Iligan City, Philippines. A descriptive case study approach was adopted to conduct an investigation.

A case study “is a general term for the exploration of an individual, group or phenomenon” (Sturman, 1997, p. 61). A case study is a narrative about individuals, organizations, processes, services, and even events. The case analysis offers a detailed understanding by collecting the comprehensive details of the case. Evaluating the progress and difficulty of a project is useful. If there is a particular narrative to be told, to address questions such as what occurred in the program and how it transpired, case studies are suitable. Moreover, a case study may be based on a single or several cases (Yin, 2003). Accordingly, the descriptive research study intends to acquire data concerning the current situation and will possibly draw conclusions from the facts discussed (Zikmund, 2000).

The case target was the ICT literacy training of marginalized girls and women extension project of the College of Computer Studies, MSU-Iligan Institute of Technology in Iligan City, Philippine. The study mainly targets the perspectives on their individual empowerment of the women and girls who participated in the ICT literacy training and evaluation of the training program.

The Case Study

The case target for this study is the extension project of the College of Computer Studies of MSU-Iligan Institute of Technology (MSU-IIT)—the “ICT Literacy Training”—which is providing ICT skills mainly to marginalized women and girls in Iligan City, Philippines. The extension project is supported by the Gender and Development (GAD) Center of the Institute and the GAD Center of the Local Government Unit (LGU)-Iligan. The project duration was March to August 2019.

The MSU-IIT Department of Extension (n.d.) mission is to “deliver effective and responsive extension services that will enable the people to improve their quality of lives towards sustainable development”, and one of the key areas is the Education and Training Program.

The MSU-IIT Gender and Development Center (n.d.) mission is “to serve as the support structure for the efficient and effective mainstreaming of gender plans, programs, and activities into the areas of instruction, research, extension, and production in the Institute and the local community for the advancement of RA 7192.”

This study was conducted in Iligan City, located in the province of Lanao del Norte in the Philippines (see map in Figure 6). Iligan City (http://www.iligan.gov.ph/ about-iligan/) is situated in Northern Mindanao (Region 10), approximately 800 kilometers southeast of Manila. It has a land area of 81,337 hectares (813.37 sq. km.) with 44 barangays (administrative divisions). The major dialect is Cebuano but languages spoken by other cultural minorities like Higaonons, Maranao, and Kolibugan, are also present. Although it is classified as highly urbanized, since it is located in Mindanao, the ICT development in this region lags behind that of Luzon and Visayas (Marcelo, 2018).

Data Collection Method

As this is a case study, to have the most complete picture possible, it depends on various sources of information and methods. Moreover, this study utilized both qualitative and quantitative research methods as these are complementary and can be mixed (Das, 1983). All the data were collected during the field study in Iligan City, Philippines, in March to August 2019.

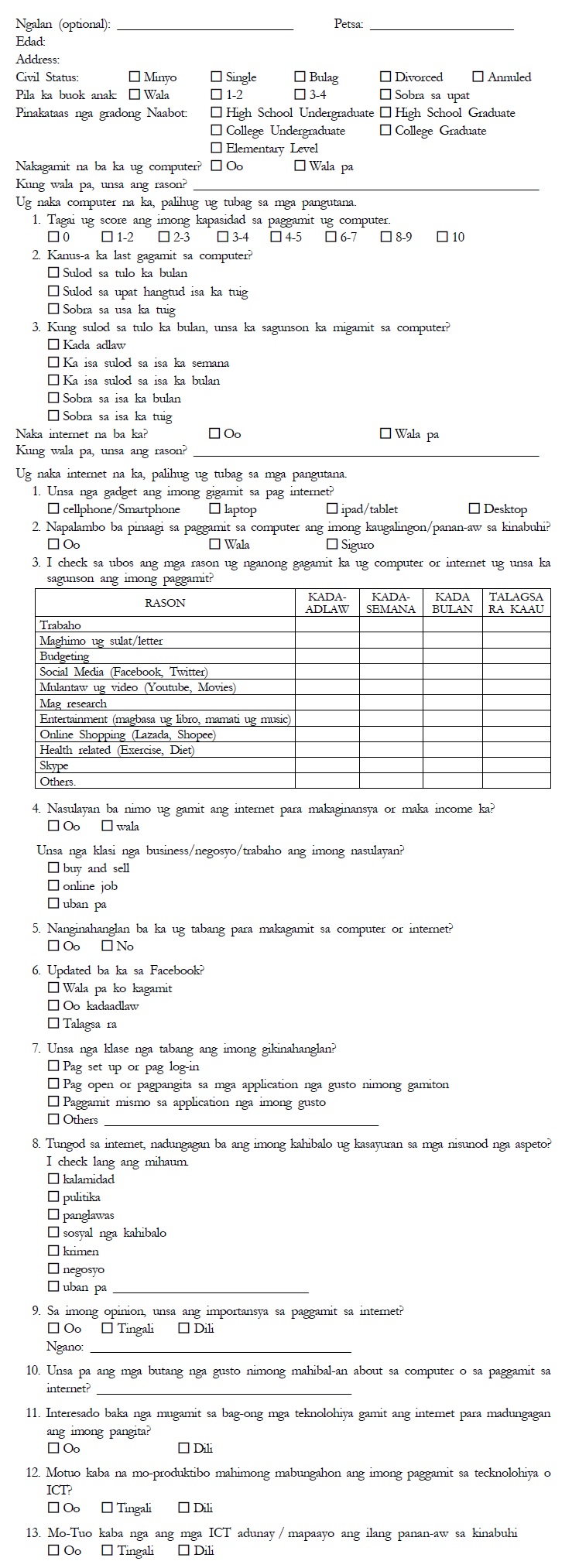

The quantitative method used in this study comprised the questionnaires. Two sets of questionnaires were given. The first questionnaire was prior to the training. To identify the forty participants, a survey questionnaire (shown in Appendix A) was given to interested participants that belong to a marginalized group in Iligan City prior to the capacity building. This was carried out with the help of GAD-Iligan, our community extension partner, using a convenience sampling method.

The second questionnaire (shown in Appendix B) was given to the participants in the ICT Literacy training. The questions were structured according to the above-mentioned core outcome indicators and divided into four categories: basic personal details of the participants, attitude towards training, skills gained during training, and training suggestions. The questionnaire had 16 open-ended questions in total.

A qualitative research approach provides “rich data about real life people and situations and being more able to make sense of behavior and to understand behavior within its wider context” (De Vaus, 2014, p. 6). It comprises an inquiry that “seeks answers to a question, systematically uses a predefined set of procedures to answer the question, collects evidence, produces findings that were not determined in advance, and produces findings that are applicable beyond the immediate boundaries of the study” (Mack et al., 2005, p. 1). The qualitative methods used in the data collection were interview and observation.

- ∙ InterviewIn-depth interviews are effective for gathering information regarding the personal backgrounds, viewpoints, and experiences of individuals, particularly when discussing sensitive topics (Mack et al., 2005).The informal interviews were all face-to-face and were conducted in a mixture of both Cebuano and English. In this study, the informal interviews were conducted by Ma’am Laura Fe Diaz, who personally handpicked the interested participants for the training after the survey. The interview mainly focuses on individuals’ personal histories and experiences. This was done in particular to identify participants who had not attended college, not working, and were computer illiterate.

- ∙ Observation:Participant observation is suitable for collecting data on natural events in everyday contexts (Mack et al., 2005).During the ICT training, the authors were also trainers.

Data Analysis

To analyze quantitative data, a statistical method was used. The quantitative and qualitative data were then categorized according to the evaluation framework. Lastly, the evaluation of the outcome of the ICT literacy training was carried out using the evaluation framework.

Validity and Reliability

Validity is the ability of an instrument, like a survey, to measure what it is intended to measure: an assessment of its accuracy (Golafshani, 2003). Unless it is reliable, an instrument cannot be valid. The questions in the questionnaires provided to participants were formulated in a clear and easily comprehensible form to ensure validity and reliability. Also, to prevent confusion, the participants could ask questions about the questionnaire while answering them. To improve the validity of the study, participants were requested to give a short explanation of their responses to some questions instead of a direct “yes” or “no” answer. Moreover, the questionnaires answered by the participants were in the Bisaya or Cebuano languages to guarantee everyone could grasp the questions.

Ethical Issues

The respondents in this study agreed to participate voluntarily. Pertinent information regarding this study, including the objectives and procedures, were thoroughly presented to all participants. Although all participants agreed to participate, they were free to drop out anytime. All the information gathered in this study pertaining to the participants was treated as strictly confidential.

Results and Discussion

The training objectives are to build confidence and skills in using computer technology for employment opportunities by providing training on ICT literacy that will promote sustainable development; and to support gender equality and women empowerment.

Project Strategy

The main strategy for this project was to identify participants for the training by having candidates voluntarily answer the questionnaire and complete an informal interview with our extension-partner, GAD-Iligan.

GAD-Iligan personnel distributed questionnaires to 44 barangays of Iligan City using a convenience sampling method. Two hundred questionnaires were given to the office of GAD-Iligan, but only 114 were filled and returned, and only 90 of the respondents were women. Since the purpose of the survey was to identify 40 participants for batch 1 of the ICT training, 90 respondents was sufficient. The main purpose of the survey was to identify their ICT competency level, their ICT experience and opinions, and the ICT skills they wished to learn. Table 2 below shows a summary of the applicants’ survey responses, their demographics, perception, and experience with ICT. Most of the applicants were young adults aged 15–25 and 26–35 years, and the majority were high school graduates (73%).

All 90 respondents claimed to have used the computer or internet at least once in their life. Almost 68% of the participants were using their smartphone to access the net, while others were using tablets, laptops, or desktops. Further, all of the participants agreed on the need for assistance in using the computer, in terms of searching, opening, and using application software (81%), computer set-up (16%), and even coding (1%). In fact, the majority of them, around 52%, rated themselves as being below average in terms of their capacity to use a computer. These were the people who rated themselves below four, ten being the highest. The majority had used a computer within the last three months, with 27% using computers every day, 38.9% once a week, and more than 11% once a month. Lastly, participants were eager to learn how to use MS PowerPoint, MS Word, and MS Excel, how to browse the internet, and perform graphics editing, as well as some basic computer functions such as encoding.

Despite the lack of ICT literacy and competency of the participants, 78% believed that ICT would in some way improved their life outlook, while 11% were not sure if ICT would have an impact on their life.

Since there are 90 applicants and only 40 were needed for batch 1 training, the head of GAD-Iligan informally interviewed the applicants and personally handpicked the participants based on the basic requirements: women living in poverty, unemployed, with at least an elementary level education (can read and write) but with no ICT training experience.

Infrastructure

Forty computers (Intel Core Duo E5200 2.5 GHz, 2 M L2 Cache, 800 Mhz FSB, 2 GB DDR2 800 Mhz) in the computer laboratory (Figure 7) of the college were used during the training.

Training Pedagogy

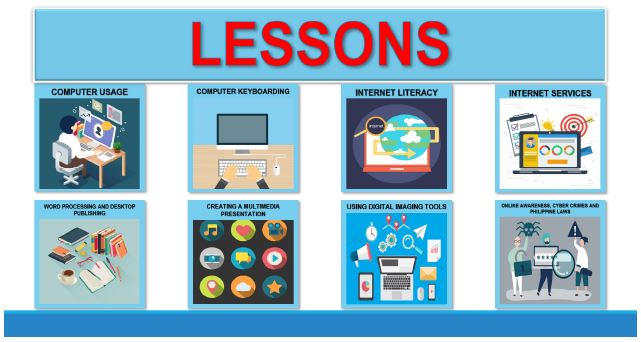

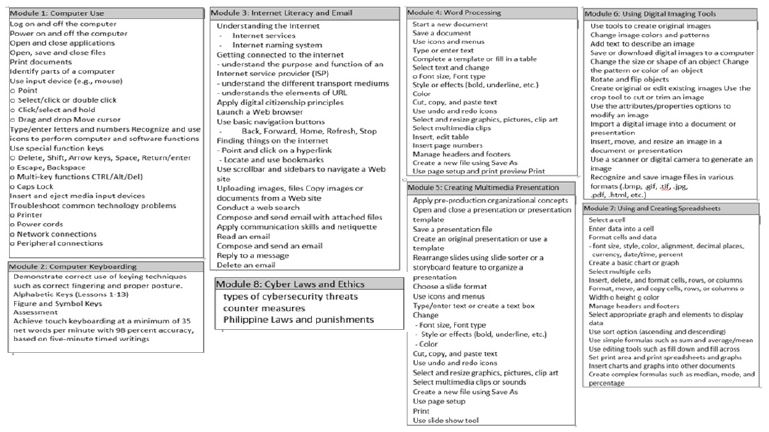

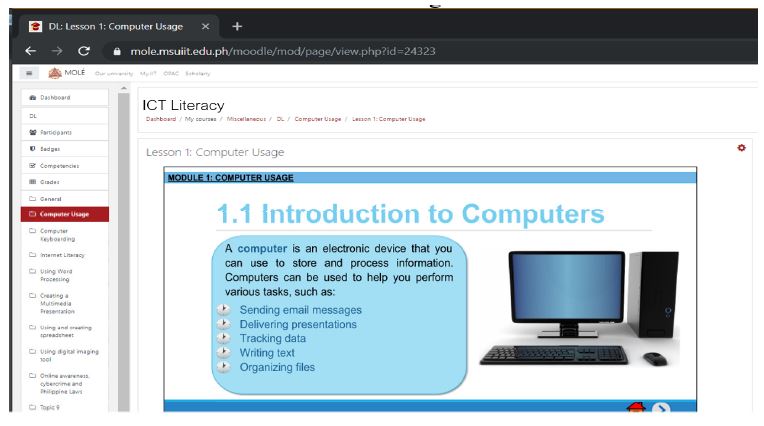

The training consisted of 56 hours spread over 7 weeks (8 hours per week). The training allowed participants to familiarize themselves with computers and learn basic computer competencies such as mouse and computer keyboarding skills, computer applications, and cyber laws. Before training, an e-learning module was developed and was used during the training to tackle foundational computer literacy skills and ICT competencies. Figure 8 shows the introduction screen of the module.

Figure 9 shows the topics covered by the sub-modules. These modules addressed the Sustainable Development Goals for education SDG 4, specifically target 4.4, “By 2030, substantially increase the number of youth and adults who have relevant skills, including technical and vocational skills, for employment, decent jobs and entrepreneurship” and indicator 4.4.1 “[increase] the proportion of youth/adults with ICT skills, by type of skill” (UIS, 2018, p. 110).

To evaluate ICT skills, the module was integrated with the skills proposed by UIS. The module excludes computer programming (it will be a different program), but added digital imaging tools and cyber laws and ethics that we thought were important.

This was uploaded in MOLE (MSU-IIT Online Learning Environment), an online learning environment used by MSU-IIT, as shown in Figure 10.

To ensure that the participants could perform the assigned practice tasks, they had to work alone at their designated workstations. Four laboratory assistants were always present during the training to assist participants and trainers. The trainers were faculty of the College of Computer Studies, and the laboratory assistants were laboratory technicians and IT student volunteers from the college.

At the end of the training, participants had to take the assessment to received training certificates; 100% of them passed the exams, which were designed by the trainers.

Information on Participants

As mentioned, the participants were women living in poverty, unemployed, with at least an elementary education but no ICT training experience. This was done to provide ICT literacy for marginalized women in Iligan City, to build their confidence and ICT skills in using computer technology for employment opportunities, and to promote sustainable development and support gender equality and women empowerment. The statistical information is displayed below.

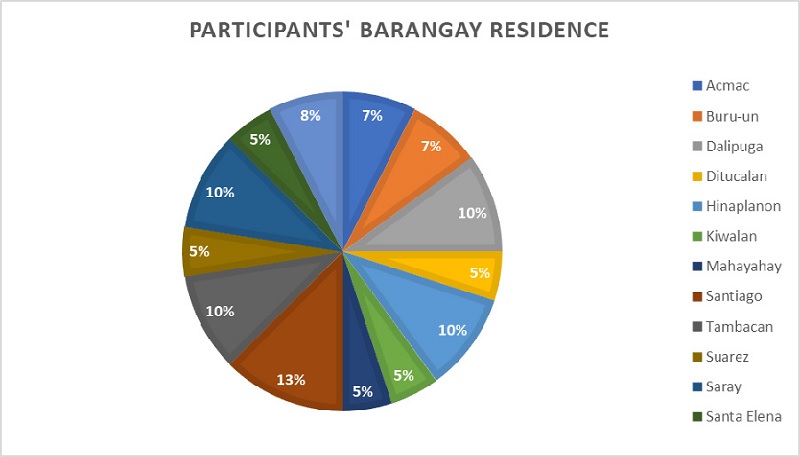

As shown in Table 3 and Figure 11, participants were aged 15–46 years old and resided in Barangay Acmac, Buru-un, Dalipuga, Ditucalan, Hinaplanon, Kiwalan, Mahayahay, Santiago, Tambacan and Suarez.

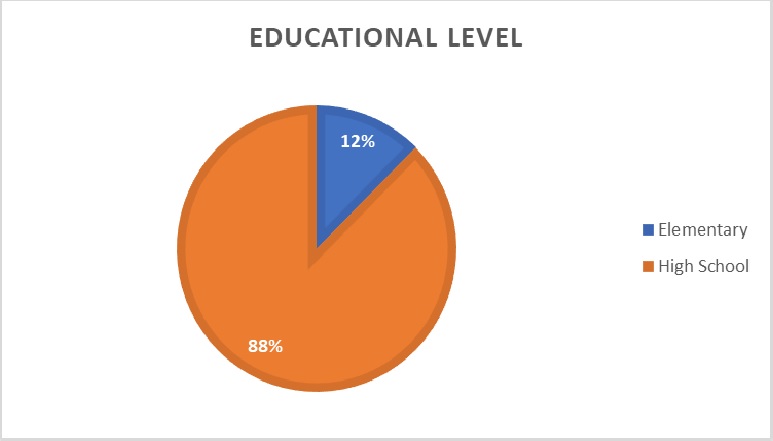

As shown in Figure 12, most of the participants (88%) were high school graduates and only 12% were elementary graduates.

Individual Empowerment

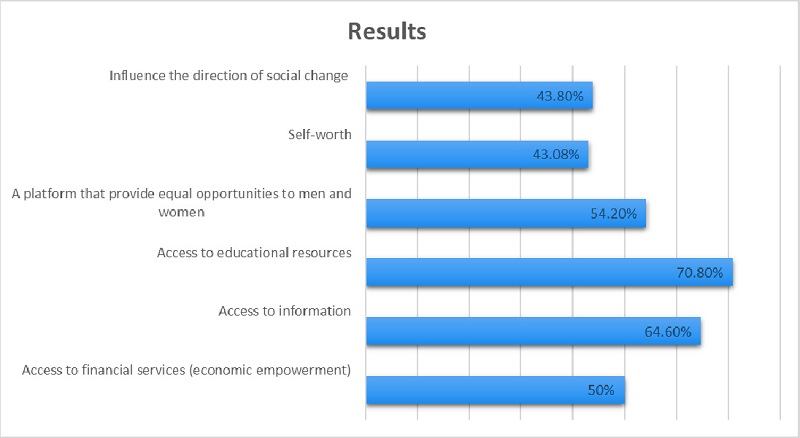

To assess the level of individual empowerment, the indicators in the evaluation framework were used to assess the participants. The core outcome indicators were attitude and skills obtained. Table 4 shows the result of the evaluation of the participants’ attitude, while Table 5 and Figure 12 show the results of their gained skills.

Participant attitude

It should be noted that participants were very interested in training and were very satisfied. When asked why they were interested in training, the majority said to learn, to become computer literate, and to get a job. All of them were satisfied with the training and trainers and would like to recommend it to their friends or others. Twenty-one of them said the trainers were kind and good at helping them. They were also satisfied with the course content, because it was easy to follow, good, and they learned from it.

Skills Gained during Training

The participants were also asked whether they had more ICT skills after training, and all of them said “yes” Mostly, they learned about operating computers, their typing skills improved, they learned how to surf the internet and use MS Word, Excel, and PowerPoint, and how to use photoshop to edit images. They were also interested in advanced training.

In addition, prior to and after training, a preliminary and post-assessment was carried out to measure what the participants had learned during training. For both evaluations, the same set of questions were given. Overall, based on the participants’ points prior to training and their points after training, it can be noted that the participants did learn from training. The pre-test average score was 20.38, with a highest score of 37.50 and a lowest score of 7.5, while the average score for the post-test was 72.63, with a highest post-test score of 97.50 and a lowest score of 50.00. The result was 0.6, based on a calculation of the normalized-gain test, which shows a substantial improvement in their scores after training in ICT literacy.

At the end of the post-survey, 100% responded yes when asked whether the training had empowered them. Figure 13 shows the summary of how participantsthought they were empowered after training based on the post-survey. Most women after the training have been empowered on their ability to access educational resources (70.80%) and their ability to access information (64.60%). These results may have something to do with the participants’ highest educational attainment of which most of them have only reached high school. Further, this empowerment has concurred to the survey results of which most of their reasons why ICTs are important is for them to be able to learn and be updated. Second is on their ability to equate the opportunities afforded to men and women (54.20%) and their ability to access financial services (50%). These results may represent the need for women to be financially independent. Because of the lack of education, they may have found a new opportunity for a business platform where they own their own time without a need for big capital. Lastly, women have found self-worth (43.80) in using the computer and feel that they can use ICT as tool for promoting just and humane society 43.80%) as their reach is expanded virtually.

Discussion

Empowerment is the course of improving one’s life to becoming better and more assured. This paper conducted a case study approach to evaluate the ICT training of marginalized girls and women based on individual empowerment. The core outcome indicators—the participants’ attitude and the skills obtained during training—were the determinants for assessing individual empowerment. The participants were aware of the significance of having ICT skills and their desire for empowerment gave them the impetus and conviction to undertake the training. The ICT training enhanced the participants’ computer self-efficacy. They perceived that throughout the training, technical skills were strengthened. Now better able to keep up with the high pace of technology advancement, most participants were more positive and hopeful. Moreover, they were also satisfied with the course material used in training and their trainers. Based on the assessment, it is clear that their skills improved.

That women can be empowered through ICT training has been asserted in the studies by Wagner et al. (2005), Khan and Ghadially (2010), Beena and Mathur (2012), O’Neil et al. (2014), Cummings and O’Neil (2015), and Rathi and Nyogi (2015), and the results of this study support those claims.

It is important to emphasize that disadvantaged groups need government, community support, and even support from academic institutions. Policies and programs on ICT such as capacity building and free access to ICTs are vital to stimulate their confidence by giving them a direction and opportunities to prosper in life. The primary driver of the digital divide is the lack of facilities, regarding which there is an obvious disparity across the Philippine region. Among the evident digital divide experiences common to all participants was difficulty in accessing the internet and the inadequacy of computer resources. Although some have cell phones, none of the participants included in our study had personal computers of their own.

Conclusion

The findings of this study imply that there is a need for ICT funding for marginalized communities because ICT skills training is a potentially high impact tool that can empower deprived groups. Moreover, academic institutions can help as part of their community extension program since they have the labor resources and facilities. In this digital era, being ICT literate can help them to be more productive now and in the future and will give them the opportunity to compete in the intellectual workforce rather than being left behind in today’s fast ICT- and information- driven economy. That being said, there should also be long-term sustainable approaches to overcoming the gender digital divide in the community. As for marginalized women, it is vital to stimulate their confidence by giving them every means in their capacity to see the potential that lies dormant within them. An accurate blueprint to nurture, polish, and sharpen those skills can only be created through education awareness and the space to freely express oneself. ICT literacy training can foster economic independence, especially for those women who are financially dependent on others. ICT skills is a potentially high impact tool that can empower deprived or marginalized groups and facilitate digital inclusion.

To examine how ICT training empowers marginalized women and girls, this paper conducted a case study. Future research could adopt a similar framework to this study to analyze similar training projects aimed at individual empowerment. In addition, to analyze the degree of empowerment more deeply, it is recommended that the participants be keep track of for future studies.

References

- ADB & UN Women. (2018). Gender equality and the Sustainable Development Goals in Asia and the Pacific: Baseline and pathways for transformative change by 2030. Retrieved from https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/461211/gender-equality-sdgsasia-pacific.pdf

-

Antonio, A., & Tuffley, D. (2014). The gender digital divide in developing countries. Future Internet, 6(4), 673–687.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/fi6040673]

- Australian Council for Educational Research. (2016). A global measure of digital and ICT literacy skills. UNESCO. Retrieved from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000245577

- Beena, M., & Mathur, M. (2012). Role of ICT education for women empowerment. International Journal of Economics and Research, 3(3), 164–172.

-

Bitanga, M. (2013). Impact assessment of iSchools Project to the public high schools teacher in Northern Luzon. IAMURE International Journal of Education, 7(1), 1. Retrieved from https://ejournals.ph/article.php?id=3267

[https://doi.org/10.7718/iamure.ije.v7i1.559]

- Bystydzienski, J. M. (1992). Introduction. In J. M. Bystydzienski (Ed.), Women transforming politics: Worldwide Strategies for Empowerment (pp. 1–10). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Cummings, C., & O’Neil, T. (2015). Do digital information and communications technologies increase the voice and influence of women and girls? London, UK: Overseas Development Institute. Retrieved from http://cdn.basw.co.uk/upload/basw_121940-10.pdf

- Dalberg Global Development Advisors. (2017). ICT skills for girls and women in Southeast Asia. Tokyo, Japan: Sasakawa Peace Foundation and Dalberg Global Development Advisors. Retrieved from https://www.spf.org/awif/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/ICT-SKILLS-FOR-GIRLS-AND-WOMEN.pdf

-

Das, T. (1983). Qualitative research in organizational behaviour. Journal of Management Studies, 20(3), 301–314.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1983.tb00209.x]

-

De Vaus, D. A. (2014). Surveys in social research. (6th ed). Australia: UCL Press.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203519196]

- DICT. (2017). National broadband plan: Building infostructures for a digital nation. Retrieved from https://dict.gov.ph/national-broadband-plan/

- DICT. (2019). ICT Trainings. Retrieved from https://dict.gov.ph/ict-trainings/

- DICT. (2020). DICT leads ICT training for teachers in MIMAROPA and Bicol Regions. Retrieved from https://dict.gov.ph/dict-leads-ict-training-for-teachers-in-mimaropa-and-bicol-regions/

- Dutt, K. (2017). The role of adult literacy in transforming the lives of women in rural India: Overcoming gender inequalities [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Stockholm University. Retrieved from https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1074266/FULLTEXT01.pdf

- Echeminada, P. (2013, March 14). IBM, client donate learning kiosks to Pasay schools. The Philippine Star, Retrieved from https://www.philstar.com/other-sections/ education-and-home/2013/03/14/919448/ibm-client-donate-learning-kiosks-pasayschools

- Eldred, J. (2013). Literacy and women’s empowerment: Stories of success and inspiration. Hamburg, Germany: UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning.

- Eyben, R. (2011). Supporting pathways of women’s empowerment: A brief guide for international development organisations. Brighton, UK: Pathways of Women’s Empowerment Research Programme, Institute of Development Studies. Retrieved from https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/20.500.12413/5847

- Foundation for Media Alternatives. (2017, April 9). Foundation for media alternatives launches Philippine gender report card. Retrieved from https://www.fma.ph/2017/04/ 09/foundation-media-alternatives-launches-philippine-gender-report-card/

- Friedmann, J. (1992). Empowerment: The Politics of Alternative Development. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

-

Friemel, T. (2014). The digital divide has grown old: Determinants of a digital divide among seniors. New Media & Society, 18(2), 313–331.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814538648]

- Gigler, B. (2004). Including the excluded—Can ICTs empower poor communities? Towards an alternative evaluation framework based on the capability approach. 4th International Conference on the Capability Approach. 5(7). Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=3171994

- Golafshani, N. (2003). Understanding reliability and validity in qualitative research. The Qualitative Report, 8(4), 597–607.

- Good Things Foundation. (2016). Digital literacy in the Philippines: A pilot project. Retrieved from https://www.goodthingsfoundation.org/sites/default/files/phillippines_pilot_ report_v2.pdf

- GSMA Intelligence. (2018). Connected women: The mobile gender gap report 2018. London, UK: GSMA. Retrieved from https://www.gsma.com/

- Gurumurthy, A. (2004). Gender and ICTS: Overview report. BRIDGE Cutting Edge Pack. Brighton, UK: Institute of Development Studies.

- Hafkin, N. (2002, July). Is ICT gender neutral? A gender analysis of six case studies of multi-donor ICT projects. Paper presented at the United Nations INSTRAW Virtual Seminar on Gender and ICT. Retrieved from www.uninstraw.org/en/docs/gender _and_ict/Hafkin.pdf

-

Hilbert, M. (2011). Digital gender divide or technologically empowered women in developing countries? A typical case of lies, damned lies and statistics. Women’s Studies International Forum, 34(6), 479–489.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2011.07.001]

- Huyer, S., & Sikoska, T. (2003). Overcoming the gender digital divide: Understanding ICTs and their potential for the empowerment of women. Instraw Research Paper Series No. 1. Retrieved from https://www.onlinewomeninpolitics.org/beijing12/ 2003_gender_ict.pdf

- International ICT Literacy Panel. (2002). Digital transformation: A framework for ICT literacy. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service. Retrieved from http://www.ets. org/Media/Tests/Information_and_Communication_Technology_Literacy/ictreport.pdf

-

Itaas, E. (2011). Capacity-building for Philippine public secondary school teachers on the Information and Communications Technology Literacy Training Program. JPAIR Multidisciplinary Research Journal, 2(1), 1–13.

[https://doi.org/10.7719/jpair.v2i1.59]

- ITU. (2018). Measuring the Information Society report — executive summary. Geneva, Switzerland: ITU Publications. Retrieved from https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Documents/ publications/misr2018/MISR2018-ES-PDF-E.pdf

- ITU. (2019). The ICT Development Index (IDI): Conceptual framework and methodology. Geneva: ITU Publications. Retrieved from https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-/Statistics/ Pages/publications/mis2017/methodology.aspx

- Keniston, K., & Kumar, D. (2003). The four digital divides. Delhi, India: Sage Publishers.

-

Kenkarasseril, M. (2013). Critical theory for women empowerment through ICT studies. Qualitative Research Journal, 13, 163–177.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-01-2013-0002]

-

Khan, F., & Ghadially, R. (2010). Empowerment through ICT education, access and use: A gender analysis of Muslim youth in India. Journal of International Development, 2(5), 659–673.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1718]

- Knowledge Community. (2020). ICT in education training program. Knowledge Community, Incorporated. Retrieved from http://knowledgecommunity.ph/services/ workshops/ict-for-education/

- Kularski, C., & Moller, S. (2012). The digital divide as a continuation of traditional systems of inequality. Sociology 5151, 1–23. Retrieved from http://papers.cmkularski. net/documents/20121214-2699.pdf

- Laizu, Z., Armarego, J., & Sudweeks, F. (2010, June 15–18). The role of ICT in women’s empowerment in rural Bangladesh. Paper presented at the 7th International Conference on Cultural Attitudes towards Technology and Communication, Vancouver, Canada. Retrieved from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/11234874.pdf

- Lennie, J. (2001). Troubling empowerment: An evaluation and critique of a feminist action re search project involving rural women and interactive communication technologies [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. Faculty of Business, Queensland University of Technology. Retrieved from https://eprints.qut.edu.au/18365/1/June%20Lennie%20Thesis.pdf

- Lennie, J., Hearn, G., Simpson, L., Kennedy da Silva, E., Kimber, M., & Hanrahan, M. (2004). Building community capacity in evaluating IT projects: Outcomes of the LEARNERS Project. Brisbane, Autralia: Creative Industries Research and Applications Centre and Service Leadership and Innovation Research Program, Queensland University of Technology. Retrieved from https://core.ac.uk/download/ pdf/10875749.pdf

-

Lennie, J. (2002). Rural Women’s Empowerment in a Communication Technology Project: some Contradictory Effects. Rural Society, 12(3), 224–245.

[https://doi.org/10.5172/rsj.12.3.224]

-

Lorenzo, A., & Lorenzo, B. (2013). Bridging the digital divide among public high school teachers: An adopt-a-school experience. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 103, 190–199.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.10.326]

- Luttrell, C., Quiroz, S., Scrutton, C., & Bird, K. (2009). Understanding and operationalising empowerment. ODI Working Paper 308. London, UK: Overseas Development Institute. Retrieved from https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/pu blications-opinion-files/5500.pdf

- Mack, N., Woodsong, C., MacQueen, K., Guest, G., & Namey, E. (2005). Qualitative research methods: A data collector’s field guide. Research Triangle Park, NC: Family Health International. Retrieved from https://www.fhi360.org/sites/default/files/ media/documents/Qualitative%20Research%20Methods%20-%20A%20Data%20 Collector's%20Field%20Guide.pdf

- Manaog, N. (2011, July 6). CapSU promotes CICT’s iSchools project across Capiz. Retrieved from http://thecapsumonitor.blogspot.com/2011/07/

- Marcelo, P. P. C. (2018, January 8). The Internet even slower down South. Business World. Retrieved from https://www.bworldonline.com/internet-even-slower-down-south/

- Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. (2017). Final report: Study on infrastructure development in Mindanao, Philippines. Retrieved from https://www.meti.go.jp/meti_lib/ report/H28FY/000056.pdf

- MSU-IIT Department of Extension. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.msuiit.edu.ph/ offices/ovcre/extension/index.php

- MSU-IIT Gender and Development Center. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.msuiit. edu.ph/offices/ovcre/gad/index.php

-

Narayan, D. (2005). Conceptual framework and methodological challenges. In D. Narayan (Ed.), Measuring empowerment: Cross-disciplinary perspectives (pp. 1–39). Washington, DC: The World Bank.

[https://doi.org/10.1037/e597202012-001]

-

Nemer, D. (2015). Digital divide to digital inclusion and beyond. The Journal of Community Informatics, 11(1).

[https://doi.org/10.15353/joci.v11i1.2857]

-

Njoki, M., & Wabwoba, F. (2015). The role of ICT in social inclusion: A review of literature. International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR), 4(12). 380–387.

[https://doi.org/10.21275/v4i12.NOV151897]

-

O’Donnell, A., & Sweetman, C. (2018). Introduction: Gender, development and ICTs. Gender & Development, 26, 217–229.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2018.1489952]

- O’Donnell, S., Ellen, D., Duggan, C., & Dunne, K. (2003). Building the Information Society in Europe: A Pathway Approach to Employment Interventions for Disadvantaged Groups. Dublin, Ireland: Itech Research. Retrieved from: http://susanodo.ca/wpcontent/ uploads/2017/06/2003-Pathways-ODonnell.pdf

- O’Neil, T., Domingo, P., & Valters, C. (2014). Progress on women’s empowerment: From technical fixes to political action. Development Progress Working Paper No. 6. London, UK: ODI. Retrieved from https://www.odi.org/publications/8996-progress -womens-empowerment-technical-fixes-political-action

- Olatokun, W. M. (2007). Availability, accessibility and use of ICTs by Nigerian women academics. Malaysian Journal of Library & Information Science, 12(2), 13–33.

- Open Textbooks for Hongkong. (2015, August 4). The World is Flat. Retrieved from http://www.opentextbooks.org.hk/ditatopic/18566

- Pablo, M. (2018, October 24). Internet inaccessibility plagues social media capital of the world. The Asia Foundation. Retrieved from https://asiafoundation.org/2018/10/24/internet- inaccessibility-plagues-social-media-capital-of-the-world/

-

Paul, A., & Thompson, M. (2018). Negotiating digital spaces in everyday life: A case study of Indian women and their digital use. First Monday, 23(11).

[https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v23i11.9325]

- Rathi, S., & Nyogi, S. (2015). Role of ICT in women empowerment. Advances in Economics and Business Management, 2(5), 519–521.

-

Roberts, T., & Hernandez, K. (2019). Digital access is not binary: The 5‘A’s of technology access in the Philippines. Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 85(4).

[https://doi.org/10.1002/isd2.12084]

- Rodrigo, M. M. T. (2001). Information and communication technology use in Philippine public and private schools. Loyola Schools Review: School of Science and Engineering, 1, 122–139.

-

Rowlands, J. (1997). Questioning empowerment: Working with women in Honduras. Oxford, UK: Oxfam.

[https://doi.org/10.3362/9780855988364]

- Sturman, A. (1997). Case study methods. In J. P. Keeves (Ed.), Educational research, methodology and measurement: An international handbook (2nd ed., pp. 61–66). Oxford, UK: Pergamon.

- UIL. (2013). 2nd global report on adult learning and education: Rethinking literacy. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0022/002224/222407E.pdf

- UNESCO. (2006). Literacy initiative for empowerment 2005–2015 vision and strategy paper (2nd ed.). Paris, France: UNESCO, Basic Education Division Education Sector.

- UNESCO. (2006). The Right to Education. Paris, France: UNESCO. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000147125

- UNESCO. (2016). Global Education Monitoring Report 2016. Education for people and planet: Creating sustainable futures for all. Paris, France: UNESCO.

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2018). SDG 4 DATA DIGEST 2018: Data to nurture learning. Retrieved from http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents /sdg4-data-digest-data-nurture-learning-2018-en.pdf

- UN Women. (2005). Gender equality and empowerment of women through ICT. UN Division for the Advancement of Women, Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat. Retrieved from www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/public/w2000-09.05-ict-e.pdf

-

Van Dijk, J., & Hacker, K. (2003). The digital divide as a complex and dynamic phenomenon. The Information Society: an International Journal, 19(4), 315–326.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/01972240309487]

- Wagner, D. A., Day, B., James, T., Kozma, R. B., Miller, J., & Unwin, T. (2005). Monitoring and evaluation of ICT in education projects. Washington, DC: infoDev/World Bank. Retrieved from http://www.infodev.org/infodev-files/resource/InfodevDocuments_9.pdf

- Wamala, C. (2012). Empowering women through ICT. Spider ICT4D Series No. 4. Stockholm, Sweden: Universitetsservice US-AB. Retrieved from https://spidercenter.org/files/2017/01/Spider-ICT4D-series-4-Empowering-women-through-ICT.pdf

- West, D. (2015). Digital divide: Improving Internet access in the developing world through affordable services and diverse content. Washington, DC: Center for Technology Innovation at Brookings. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/West_Internet-Access.pdf

- Wetheridge, L. (2016). Girls’ and women’s literacy with a lifelong learning perspective: Issues, trends and implications for the Sustainable Development Goals. Paris, France: UNESCO. Retrieved from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/143614833.pdf

-

Woolcock, M., & D. Narayan. (2000). Social Capital: Implications for Development Theory, Research and Policy. World Bank Research Observations, 15(2), 225–249.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/15.2.225]

- World Wide Web Foundation. (2014). ICTs for empowerment of women and girls: A research and policy advocacy initiative on empowering women on and through the web in 10 countries. Retrieved from http://webfoundation.org/docs/2015/05/WROProjectFramework.pdf

- Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Zickur, K., & Smith, A. (2012). Digital differences. Retrieved from https://www.pewinternet.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/9/media/Files/Reports/2012/PIP_Digital_differences_041312.pdf

- Zikmund, W. G. (2000). Business Research Methods (6th ed.). Mason, OH: Harcourt.

Appendix

Appendix B Training Participants’ Questionnaire

Ngalan (Name):Gender:Edad (Age):Level sa Edukasyon (Educational Level):Trabaho (Occupation):

Estudyante ka ba karon o nagtrabaho?Currently, are you a student or working?

Aduna ka ba kaugalingon nga computer o laptop?Do you have your own computer or laptop?

Ngano nga interesado ka sa pagbansay o training sa literasya sa ICT?Why are you interested in ICT literacy training?

Ngano nga gipili nimo kin inga programa sa pagbansay?Why did you choose this training program?

Niapil ba ka sa uban pang kurso sa pagbansay sa computer kaniadto?Have you participated in other computer training courses before?Kung oo, unsa kini ug unsa na kadugay ang training?If “yes”, what is it and how long did the training last?

Unsa nga mga kahanas ang imong nahibal-an sa kini nga training o pagbansay?What skill have you learnt this training?

Lisud ba alang kanimo ang kurso?Is the course difficult for you?

Unsa nga mga kahanas sa imong hunahuna ang angay nga tudloan kanimo apan wala sa imong pagban say?What skills do you think you should have been taught but was not during the training?

Natagbaw ka ba sa mga tigbansay?Are you satisfied with the trainers?

Natubag ba niya ang imong mga pangutana?Was he/she able to answer your questions and explain them clearly?

Gibati ba nimo nga adunay kadaghang kahanas sa kompyuter karon kaysa sa pagsugod sa training?Do you feel you have more computer skills now than at the beginning of the training?

Unsa ang uban pang mga kahanas nga gipaayo sa panahon sa training?What other skills have been improved during the training?

Sa imong hunahuna, ang mga kahanas ba sa computer makatabang kanimo aron makapangita ka ug maayong trabaho?Do you think computer skills will help you find a good job?Kung oo, unsa nga trabaho ang gusto nimo buhaton pagkahuman sa training?If “yes,” what kind of job do you want to do after the training?

Irekomenda ba nimo ang imonga mga higala nga moapil kin inga programa sa pagbansay? Ngano man?Will you recommend your friends to participate in this training program? Why?

Gusto ba nimo nga magkuha usa ka advanced nga training pagkahuman sa kini nga training?Would you like to take advanced training after this program?Kung oo, unsa ang gusto nimo mahibal-an?If “yes”, what do you want to learn?

Biographical Note: January D. Febro is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Information Technology at Mindanao State University - Iligan Institute of Technology. Her current interests involve applications for sustainable development and ICT4D. Email: january.febro@g.msuiit.edu.ph

Biographical Note: Mia Amor C. Catindig is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Information Technology at Mindanao State University - Iligan Institute of Technology. Her interests are in data mining, GIS applications, and software development. Email: miaamor.catindig@g.msuiit.edu.ph

Biographical Note: Lomesindo T. Caparida is Professor of the Department of Information Technology at Mindanao State University - Iligan Institute of Technology. His current interests involve computer networks. Email: lomesindo.caparida@g.msuiit.edu.ph