Caught between State and Motherhood: The Public Image of Female Entrepreneurs in Singapore

Despite being known as a society with a high level of entrepreneurial activity, studies on female entrepreneurs in Singapore are sparse, and the proportion of women partaking in entrepreneurship remains low. As studies have shown, the socially constructed image of female entrepreneurs has the effect of either encouraging or impeding women’s entrepreneurial activities. This article explores the public image of female entrepreneurs and their changing status by tracing their media representation in Singapore’s major newspapers from the early 1980s to recently. Using content analysis from two major newspapers, we analyze how female entrepreneurs are constructed in the media and the changing discourse over time. We find that the discourse on female entrepreneurship presents persistent gender stereotypes centering on a few role models. These discourses show an embodiment of Singapore’s nationhood to encourage entrepreneurship through incorporating women’s roles at both the national economic and the domestic level to further the nation’s economic development. In recent years, while more young women entrepreneurs have emerged, their gender is seldom clearly identified in the news media unless they also embrace their roles as homemakers and child bearers. Our findings suggest that despite the government’s promotion of entrepreneurship to encourage women’s participation, the public image of a successful female entrepreneur has always been one that could contribute both to economic production and to homemaking and childbearing to further the nation. This image may subject women to the constant pressure of multiple role conflicts and also conceal alternative images of women entrepreneurs who depart from conventional stereotypes.

Keywords:

gender, entrepreneurship, women entrepreneurs, news media, SingaporeIntroduction

Singapore is known for being a highly entrepreneurial society. The city-state is constantly ranked among the top countries with an encouraging environment and high entrepreneurial activity rate. Since the country’s first post-independence recession in 1985, the Singapore government has viewed encouraging entrepreneurship as one of the fundamental development policies to cultivate a more resilient local economy. In 1987, the Sub-Committee Report on Entrepreneurial Development Economic Report called for a shift in employment culture through restructuring the education system to foster creativity, innovation, and enterprise (Shome, 2006). In 2002, Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore’s first prime minister, gave an address on “An Entrepreneurial Culture for Singapore” as the foundation of a successful economy at the Ho Rih Hwa Leadership in Asia Public Lecture at Singapore Management University (Shome, 2006).

To increase women’s participation in economic development, the Singapore government seems to have a sincere desire to promote female entrepreneurship at the policy level. In the context of this broader trend, we would assume that women’s entrepreneurship should be vibrant.1 As early as 1992, the Singapore Business and Professional Women’s Association held the first conference for women entrepreneurs. The Entrepreneurship Development Center at Nanyang Technological University started the annual Women Entrepreneurs Development Program. Singapore’s first female president, Halimah Yacob, has mentioned the importance of supporting women entrepreneurs as it “boosts women’s confidence in being able to contribute to our economy.”2 Consequently, several initiatives have been launched to support women entrepreneurs, such as the inaugural Singapore Women Entrepreneur Summit held in July 2019 in collaboration with the Women Entrepreneur Awards.

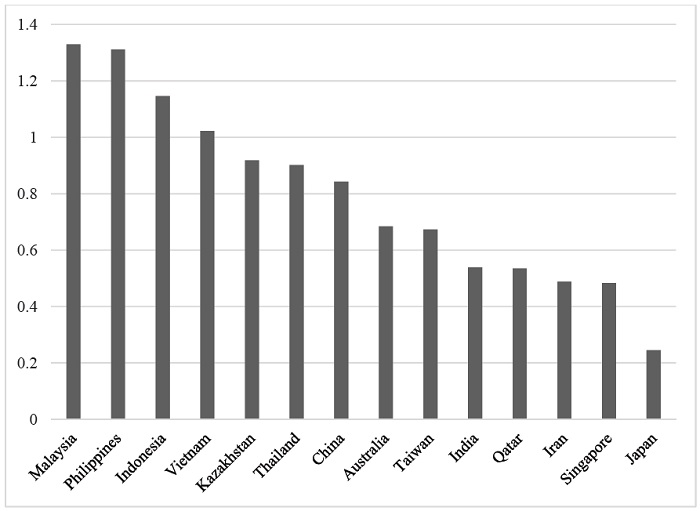

Although the government and tertiary educational institutions in Singapore have actively promoted entrepreneurship, there is a significant gap between female and male participation. Figure 1 shows that in terms of the ratio of early-stage female to male entrepreneurs from the Global Entrepreneur Monitor (GEM), Singapore is only ranked higher than Japan in Asia, and early-stage male entrepreneurs are twice as numerous as their female counterparts in Singapore.3 Similarly, findings from the recent Mastercard Report on Women Entrepreneurs indicate the possibility of a widening gender gap in Singapore. The report found that “despite being ranked 5th overall in the Index and topping the charts in 2 components (Knowledge Assets & Financial Access and Supporting Entrepreneurial Conditions),” female entrepreneurial activity rate has decreased and female entrepreneurs in Singapore “continue to be weighed down by their protracted challenges in achieving work-life balance” (Mastercard, 2018, p. 17). Given the policies and educational institutions that support the growth of entrepreneurship, how then can we understand Singapore’s significantly lower levels of female entrepreneurial activity?

Early-Stage Female to Male Entrepreneur Ratio in Asian Societies.Note. Numbers are taken from the General Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) 2014 Global Report. Retrieved August 15, 2019, from https://www.gemconsortium.org/report/49079/

The current literature on Singaporean female entrepreneurs is limited in terms of both the number of studies and their scope, with only a few after the mid-2000s. In a review article, Jean Lee (2005) called for more researchers to study this topic, but a gap in scholarly interest in this area seems to have remained ever since. One of the areas that the existing studies do not fully explore is the public discourse on female entrepreneurs in Singapore, broadly meaning the “practices of writing and speaking” of entrepreneurship (Achtenhagen & Welter, 2007, p. 193). The female entrepreneur, from this understanding, is a socially constructed category, and its meaning is continuously shaped by powerful social actors such as the mass media, government, and civic organizations.

In this article, we use the two most prominent newspapers in Singapore, The Straits Times (ST) and The Business Times (BT), to analyze the evolution of the public discourse on female entrepreneurship since 1980. These two newspapers, owned by Singapore Press Holdings (SPH), are regulated by the Newspaper and Printing Presses Act (Press Act), in which all issues and shares have to be approved by the Ministry of Information Communication and the Arts. The views from these two major newspapers not only represent accepted mainstream images but also reflect how the government wants female entrepreneurs to be represented in the nation’s quest for economic development.

This paper is the first study that examines Singaporean female entrepreneurship by analyzing newspaper content. It departs from existing studies on female entrepreneurship that tend to present work-family conflicts as the major obstacle to women’s entrepreneurship to situate the study against the backdrop of state-guided entrepreneurship and the narrative of national survival based on technopreneurship in Asia (Chua 2019; Shome, 2006). Our findings suggest that the public media’s continuous amplification of the ascribed family-related roles of women entrepreneurs, the requirement that they shoulder responsibilities on both the economic and the domestic level, may unintentionally conceal the alternative image of women entrepreneurs who pursue an unconventional lifestyle. The lack of diverse public images of women entrepreneurs in terms of age, class, race, and sexuality may perpetuate a highly unattainable female entrepreneurial role model resulting in low levels of entrepreneurship among prospective young women (Byrne, Fattoum, & Garcia, 2019).

This article is organized in the following way. In the next section, we briefly review the current literature on the socially constructed nature of female entrepreneurship, followed by a review of the literature on women entrepreneurs in Singapore. In the third section, we discuss our data and methods, and in the fourth and fifth sections, we present and discuss our findings. Finally, we conclude our paper with a discussion on the implication of our findings and the limitations of our research.

Female Entrepreneurs as a Social Construction

Gender has significant effects on entrepreneurial activity (Jennings & Brush, 2013; Yang & Aldrich, 2014). Prior research has found that compared to the ideal type of rational male entrepreneurs, female entrepreneurs are constrained by the gender stereotype in a given society, and women are seen as an inferior fit for the role of entrepreneur (Marlow & Swail, 2014; Mirchandani, 1999). As Helene Ahl (2002) has argued, this gender stereotype is a social construct produced and reproduced by powerful social institutions and serves as the evaluative tool for women (Acker, 1990). However, early studies on entrepreneurship tend to neglect the socially constructed nature of gender, and the research findings may serve to reaffirm the dominant stereotype of women (Ahl, 2006).

Since the early 2000s, more research has begun to explore the context of the entrepreneurial process and how social institutions prescribe certain gender roles for women that discourage them from being entrepreneurs (Bullough, Renko, & Abdelzaher, 2014; Orlandi, 2017; Santos, Marques, & Ferreira, 2018). Leveraging diverse methodologies, scholars of female entrepreneurship are gradually embracing the paradigmatic shift from “gender as an influence” (Marlow, 2002) to “gendered entrepreneurship” (Henry, Foss, & Ahl, 2016). Scholars have begun to examine how the entrepreneurial process is associated with femininity or masculinity, maintaining that women’s entrepreneurial behavior is constrained by both informal institutions, like social norms, and formal institutions, like laws and social policies, that significantly impact women’s entrepreneurship (Bruni, Gherardi, & Poggio, 2004; Giménez & Calabrò, 2018; Sequeira, Wang, & Peyrefitte, 2016; Stead, 2017; Welter, 2020).

With entrepreneurship highly intertwined with the national economy, the state’s influence on the overall entrepreneurial environment in shaping public attitudes toward gender roles could further deepen the gender penalty for women. In their comparative study on the state discourse on women’s entrepreneurship in Sweden and the United States, Ahl and Nelson (2015) found that although national welfare policies vary, these policies bear surprising similarities in their assumption that women entrepreneurs are different or subordinate to men. In Sweden, despite government efforts to initiate policies that promote woman’s entrepreneurship, women still shoulder family responsibilities that impede their entrepreneurial activity. Consequently, benefits for women fail to materialize, reproducing the perception of women as “other” in the field of entrepreneurship (Berglund, Ahl, Pettersson, & Tillmar, 2018).

In addition to government policies, the public representation of women entrepreneurs in the media further shapes mainstream values and the socially-acceptable entrepreneurial role models of women (Hamilton, 2013; Radu & Redien-Collot, 2008). Achtenhagen and Welter’s (2011) study of the German media has found a tendency to highlight women entrepreneurs’ exceptional success as divergent from the norm and emphasize their connection to the family. In Bobrowska and Conrad’s (2017) research on the representation of women entrepreneurs in the Japanese business press, they found that traditionally gendered discourses still prevail despite the presence of other discourses, thus positioning women as inferior to men in their entrepreneurial potential. Byrne et al. (2019) further reveal that women entrepreneur role models narrate their success through their capability to adapt to societal expectations as “superwomen” who play along with rather than challenging the existing social institutions. These findings suggest that government policies promoting gender equality and women’s entrepreneurship will not achieve results if the public media continue to portray women entrepreneurs as subordinate and their success as exceptional.

Female Entrepreneurs in Singapore

Women’s entrepreneurship remains an understudied topic in Singapore. Despite the recent favorable policy environment, most scholarly research on women entrepreneurs is over a decade old (e.g., Chew & Tan, 1991; Lee, 2005; Seet, Ahmad, & Seet, 2008). The lack of academic interest in women’s entrepreneurship is puzzling because Singapore is constantly rated as one of the best countries for women to start their own business, and the Mastercard Index of Women Entrepreneurs 2018 (MIWE) reports that 27.5% of business owners in Singapore are women. However, despite favorable conditions, Singaporean women seem to be less motivated to engage in entrepreneurial activities, as the 2018 MIWE report shows that women’s entrepreneurial activity rate decreased by 22% from 2017 (Mastercard, 2018).

The Singaporean government has been proactively promoting entrepreneurship to support the country’s economic growth. In 2002, Singapore’s first prime minister Lee Kuan Yew called for cultivating an entrepreneurial culture for Singapore because “to be successful, economies need to foster more entrepreneurs” (Shome, 2006, p. 11). Many government and quasi-government bodies were set up to work with state-sponsored universities in aggressively promoting entrepreneurship. These state initiatives included the state-owned television company MediaCorp and state-shared Singapore Press Holdings (SPH) to celebrate entrepreneurship, the stressing by political leaders like Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong of the importance of having more entrepreneurs to contribute to Singapore’s growth, an early-stage venture investment fund through the National Framework for Innovation and Enterprise (NFIE), and the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) to advance technological innovation (Anthony, 2015). Along with these state-led initiatives, women entrepreneurs were also recognized through the Woman Entrepreneur of the Year Award initiated by the Association of Small and Medium Enterprises (ASME) as early as 1999 (Singapore Government, 1999).

To date, only seven academic articles dealing directly with women entrepreneurs in Singapore have been published. Excluding Maysami and Goby’s review article (1999), the six remaining articles are mainly concerned with the same issue—who are these women entrepreneurs, and what is the difference between them and male entrepreneurs? In terms of methodology, they are mostly based on surveys of a small group of female entrepreneurs. For example, in an earlier study, Jean Lee (1996) found that Singaporean women entrepreneurs are motivated more by a need for achievement and dominance than by a need for affiliation and autonomy. In terms of the profile of these women entrepreneurs, they were middle-aged (40–44 years old), of a college education background, married, and began their business at the age of 30–34 (Lee, 1996; Teo, 1996). Another research study by Seet et al. (2008) revealed that male and female entrepreneurs in Singapore have similar motivation levels, but female entrepreneurs in Singapore are less confident and more anxious than their male counterparts. This seems to affirm the findings of an earlier study which found that Singaporean female entrepreneurs experience emotional strain arising from work-family conflict (Lee & Choo, 2001). However, none of the earlier studies highlight the inimical institutional environment and culture that leads to emotional strain, low confidence, and persistent work-family pressure as women entrepreneurs struggle to prove themselves in a male-dominant world.

Drawing insights from prior studies, our research examines the social context in which women’s entrepreneurship is constructed by investigating how the media portrays female entrepreneurs. We take inspiration from Byrne et al.’s approach (2019) in analyzing the public narrative of female entrepreneurial role models in a government-led program in France. Through our study on the evolving media representation of female entrepreneurs in Singapore, we seek to expose the dominant local female role models and their qualities in media portrayals.

Method and Data

To understand the social construction of the public image of female entrepreneurs in Singapore, we perform a systematic analysis on major newspaper articles using The Straits Times and The Business Times as our two sources. The Straits Times is the most popular English newspaper in Singapore, while The Business Times is known for reporting on business developments relevant to corporate professionals. Both are owned by Singapore Press Holdings Limited (SPH), a media arm of the Singapore government, that under the Newspaper and Printing Presses Act (or Press Act) enacted in 1974, legitimizes the management, surveillance control, and funding of newspapers in Singapore (Rajah, 2012). Therefore, these two newspapers have implicit roles as outlets for government policies, and the content strongly reflects the state-approved discourse, as previous studies have pointed out (George, 2007; Rajah, 2012).

We collected 480 articles from The Strait Times and The Business Times containing different combinations of keywords for female, woman/women, entrepreneur/ entrepreneurship, and gender from the Factiva and NewspaperSG online databases. The distribution of these articles is shown in Table 1. Based on an initial reading, we created a dataset that records the information about these articles, including publication date, author, and a short description of each. Many articles were not about women entrepreneurs but just mentioned “entrepreneur” and “women” or “female” in different parts. We identified the names of the female entrepreneurs reported since the first article in 1987 and captured the descriptive adjectives used to describe them, coding them into different categories based on their representation and connection to a women’s social role. Surprisingly, only seven female entrepreneurs (see Table 2) were repeatedly covered in the news, and they comprised 40% of all the news reports. While Singapore is a multiracial country, all seven of them are of Chinese descent rather than from other racial categories. Post-2010, the term “mumpreneur” began to appear, and various entrepreneurs who identified as mothers were referred to in these articles. More recent coverage of a young female entrepreneur was about Grab co-founder Tan Hooi Ling. However, none of the news articles refer to her as a female entrepreneur, and she often appeared to be genderless as a co-founder next to the more outspoken male co-founder (see Table 2).

The methodology adopted offers a critical examination through content analysis to reveal the underlying power relations in the news (e.g., Achtenhagen & Welter, 2011; Bobrowska & Conrad, 2017). All textual data were imported into MAXQDA to be coded, organized, and indexed. Using the grounded theory approach, each article was read closely by at least two authors using an open coding scheme to first allow patterns to emerge inductively through in-vivo codes (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). This allowed categories of female entrepreneurs to be constructed within their context based on the raw materials rather than relying on existing classifications (Weber, 1990).

After this open coding process, we grouped these in-vivo codes to create higher-level conceptual codes to develop four major categories representing the models of female entrepreneurs in the news data: “steel magnolia,” “dutiful wife and good mother,” “mumpreneur,” and “others.” When differences in coding and grouping were identified, the texts were reassessed until a consensus was reached, as well as overall intercoder reliability of above 90% given the exploratory nature of the study (Neuendorf, 2017). In the final phase of the coding process, the first author rechecked the codes in each major category to ensure consistency and agreement in coding was achieved (Armstrong, Gosling, Weinman, & Marteau, 1997; O’Connor & Joffe, 2020). We triangulated the emerged themes with the relevant government policies and initiatives on entrepreneurship as well as specific programs geared toward female entrepreneurship to discover patterns of public images that cohered to a particular time period.

Because there are so few relevant articles before 1980 (fewer than 10), that period is excluded. In fact, it is not until 1989 that the topic of women’s entrepreneurship gained popularity in the press, with more than half of the 46 articles in the 1980s being published in 1989. The number of articles then doubles in the 1990s and continues to grow in the 2000s and 2010s. The increasing number of related articles in these two major newspapers indicates that women’s entrepreneurship is attracting more attention, and given the media situation in Singapore, this may reflect increased government concern.

In what follows, we discuss the three major social categories of women entrepreneurs based on our examination of these 480 articles. These three major categories are women entrepreneurs as steel magnolias, women entrepreneurs as dutiful wives and good mothers, and women entrepreneurs as mumpreneurs.

Women Entrepreneurs as Steel Magnolias

Prior to 1989, women entrepreneurs in Singapore were rarely featured in the news. However, June 1989 was a significant turning point as the recipient of the “Small Businessman of the Year” award inaugurated in 1989 by the Rotary Club turned out to be a woman, and this triggered a surge in the number of articles on women entrepreneurs. Because of the extent to which the number of men outnumbered women in business and the presumedly masculine connotation implied by the word “businessman” in the award title, Miss Rachel Swee’ award was received with much surprise and confusion by the press. While the reactions were generally positive yet ambivalent, The Business Times’ renamed the “Small Businessman of the Year” award “Small Entrepreneur of the Year” (“Software Wizard,” 1989). Miss Swee was dubbed a “Software wizard” rather than an entrepreneur. Such manipulation of gendered linguistic terms reveals the ambiguous nature of female entrepreneurs in Singapore.

Following Miss Swee’s win, the woman entrepreneur became an elusive category that was treated with curiosity. This resulted in a slew of articles, especially those published in the early 1990s, which leveraged interviews as well as the authoritative voice of academia and the government to assert that a woman entrepreneur may indeed be different from her male counterpart and other women. The most prominent portrayal of women entrepreneurs in these early reports is that of the “steel magnolia” or “iron lady”—women who possessed certain masculine traits, which enabled them to thrive in a male-dominated field.4 Under this labeling, these reports often associate the success of these women entrepreneurs with certain mystical and masculine elements that are assumed to be rare in normal women. In describing such traits, authors used adjectives such as “gritty” (Guan, 1992), “hard-nosed” (Soh, 1995), and “tough” (Ee, 1997) to emphasize the exceptionally immense mental fortitude required of women entrepreneurs to survive and be successful in business. This perspective of women entrepreneurs as having an “inner strength” (Subramony, 1989) is reflected in the authors’ choice of titles during this period, like “Be strong, focused and determined” (Koh, 1999), “Perseverance and commitment” (Lim, 1991), and “Hour Glass woman made of steel” (Lim, 1990). However, authors would frequently subvert this image of strength and masculinity by revealing the feminine side of women entrepreneurs to imply that in spite of their masculine veneer, they are ultimately females at heart and that that gave them an added advantage.

The “Steel Magnolia” typology is evidenced in a representative article titled “Steel Magnolias” (Koh, 1998). In the beginning, the author depicts women entrepreneurs as impenetrable, even facing gender discrimination and prejudice because they can compete with men on an equal footing. Immediately after this image of a steely woman, the author proceeds to a new section with the subheading “A woman’s touch” and suggests that there may be a more feminine and gentle side to them that is subtle but still evident in the way that they do business, such as being adept at interpersonal communication and emotional expression which helps them to better motivate and nurture their employees.

In another article titled “Tough entrepreneur, caring boss,” the author portrays the woman entrepreneur as an alpha female for being “strong-minded” and “tough” but at the same time “sayang,” the Malay word meaning the demonstration of affection to reinforce her feminine and caring disposition. The author jestingly writes that she is willing to submit to this woman entrepreneur as if she were her pet dog:

If I were a dog, I would want to be owned by Florence Tay. I would sit in her car, drool over the seats and she would still sayang me even though I used to pick fights with her pit bull terrier at home [⋯] As a straight-talking mutt, I will tell you that not only is she a responsible dog-lover, she is also a caring employer. (Ee, 1997, p. 14)

The power dynamics expressed are thus clear: Even though the author and the female entrepreneur are both women, Ms. Tay is different from ordinary women and stands out as a capable leader who the author reveres. Despite the portrayal of a fiercely independent woman entrepreneur, the author emphasizes that Ms. Tay still retains a traditional feminine core—competent in domestic chores and caring for the well-being of her employees.

While the portrayal of women entrepreneurs as straddling femininity and masculinity in being tough and strong, yet simultaneously kind and caring, is not new, the underlying assertion behind the “steel magnolia” stereotype means that if women want to succeed in business, they need to achieve a balance between a tough exterior and a caring management style.

Women Entrepreneurs as Wives and Mothers

While the steel magnolia image is commonly used to describe the success of women entrepreneurs, the image of dutiful wives and good mothers is employed to explain why their business is sustainable and worthy of respect. Given that in 1984, Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew supported a eugenic family planning program urging highly educated women to get married and have more children, the public image of women entrepreneurs as being compatible with being good wives and mothers may not be all that negative (Reuters, 1984). This may unintentionally serve as a public shield for women who want to venture beyond the conventional trajectory at a time when the state is putting more emphasis on their reproductive role.

Dutiful Wives

Along with the steel magnolia image, the portrayal of women entrepreneurs as dutiful wives to their husbands as business partners is most evident in the 1980s to 1990s and continues in the later period. Women entrepreneurs are described as subservient to their husbands, crediting the permission and affection of their husbands for their engagement in entrepreneurial activities. The extremely successful woman entrepreneur, Ms. Jannie Chan, was widely reported as a wife who defers in her success to her co-founder husband:

Mrs. Tay attributes her success in business and personal life to three main sources—her parents, her Buddhist religion, and her husband. Her husband of 20 years, Dr. Henry Tay, 45, is officially the boss. He left his practice nine years ago to join her in the business. “Because he is my husband, I can accept him as the boss, not anyone else” Mrs. Tay says. (Subramony, 1989, p. 10)

The author’s use of “officially the boss” positions Chan’s husband as a higher authority within the company even though her husband did not initially play an active role in the business. There is also a subtle subversion of her success by the author’s highlighting of Chan’s deference to her husband that weakens the reader’s perception of her achievements as an entrepreneur. This unintentionally creates the impression of her husband as the true owner of the company and re-frames Chan as the dutiful wife who supports her husband’s success.

Reinforcing the stereotypical portrayal of the dutiful wife, “The woman behind the successful man” is another example whereby an author often stresses how a woman entrepreneur had contrasting but complementary traits that supported her co-founder husband’s success. In the article “It’s a husband-and-wife team,” the author inserted a quotation from the woman entrepreneur’s husband:

I am bad at expressing my emotions. My wife is the exact opposite. People can relate to her more [⋯] She helps me in corporate relations, staff relations and discussing business deals [⋯] She makes the difference between me being a good entrepreneur and a better entrepreneur. (Ho, 1994, p. 3)

The emphasis on the emotional qualities of the wife fails to show an equality between this husband and wife’s team but instead draws attention to how the woman entrepreneur’s feminine traits help promote her husband’s success and assist him in becoming a “better” entrepreneur. The narrative could lead the readers to assume that her husband is the real founder and forget that her husband only joined her company nine years after its foundation.

Good Mothers

Besides the image of dutiful wives, women entrepreneurs were continuously portrayed as good and natural mothers. Several articles during this period constructed a nurturing and caring image of women entrepreneurs as mothers. For instance, one author recounts the dialogue between a woman entrepreneur and her hearing-impaired daughter during an interview to emphasize the emotional bond between the mother and daughter:

[My daughter] Sabrina is my biggest success. Nothing is impossible if you believe that anything is possible. I wanted Sabrina to feel that she is no different from any other [⋯] I exposed her to society and trained her to feel confident in herself. (Lim, 1990, p. 9)

The successful entrepreneur Ms. Tay is thus portrayed as a good mother who was responsible for cultivating her daughter’s self-esteem to help her overcome her medical condition. Attaching a photo of Tay and her daughter, the author implies that a woman values her children more than her business, thus reinforcing that women entrepreneurs should also be good mothers.

Not only is a woman entrepreneur a good mother to her children, but the news media also accentuates her role as a good mother to her employees. In an article titled “Earth mother,” the authors stressed the maternal nature of the famous woman entrepreneur Mrs. Liew, the owner of the Begawan Solo bakery chain, both at home and at work:

She is the all-embracing personification of Mother Earth herself. She breast-feeds, cooks, bakes, cleans, sews, manages—all exemplarily well. And these are indeed her heart’s dearest priorities [⋯] So, even though she might be running a successful family business, is her office’s most trusty administrator or at the peak of the nursing profession, the natural-born housewife is really after the “backbone of the family’s position” [⋯] “I feel honored to be called Auntie. In fact, all my factory staff call me Auntie. I treat them like family,” Mrs. Liew says, positively beaming. (Long, 1999, p. 9)

By drawing on the archetype of “Earth Mother” and a “natural-born housewife,” the author essentializes Mrs. Liew’s maternal qualities in that her maternal role takes precedence even when she is running the family business. Mrs. Liew is also portrayed as a woman who embraces her maternal qualities by taking pride in being called “Auntie” by the employees.

During the early period between the late 1980s to the early 2000s, women entrepreneurs are often portrayed in the combination of steel magnolia, dutiful wives, and earth mothers. The story is often narrated from the perspective of their husbands, children, employees, and other people astounded by their achievements, rather than in the women entrepreneurs’ own voices. While prior studies by Ahl (2002) have shown that publicizing the socially desirable gender norms for women entrepreneurs contributes to “othering” women entrepreneurs, these acceptable gender roles inadvertently create a space for women entrepreneurs in the pursuit of Singapore’s nationhood.

The Rise of Mumpreneurs

After the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, the government identified entrepreneurship as a means to revitalize the economy and generate jobs. During this period, the government attributed the low levels of entrepreneurship to the limited innovation capacity arising from the lack of entrepreneurial talent (Chua, 1999a). Senior Minister Lee Kuan Yew then stepped in with an example of a good entrepreneur with exceptional entrepreneurial talent. During a dinner for global chief executives in February 1999, he promoted Ms. Jannie Chan to the status of a national role model as a talented entrepreneur: “She is not just a watch seller. She is an entrepreneur—way before anyone thought there was a market for upmarket watches in Singapore.” (Tee, 1999, p. 2)

This emphasis on entrepreneurial abilities over gendered qualities began to be widely promoted by the government while existing gender stereotypes still prevailed. For example, in his 1999 National Day speech, Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong highlighted the importance of having more entrepreneurs in Singapore and called for the private sector to help rebuild Singapore’s economy. Reiterating Senior Minister Lee Kuan Yew’s perspective, he remarked: “It is talent, talent, talent, not money, money, money that will lead to success” (Chua, 1999b, p. 53). Correspondingly, we find that although terms like mothers and wives are still mentioned in the articles, the articles acknowledge the talent and abilities of selected women entrepreneurs. Women entrepreneurs were portrayed as national assets and role models with desirable traits such as resilience and innovation to contribute to economic recovery. The best case is Ms. Nanz Chong-Komo, who became known as Singapore’s “most famous failed entrepreneur” (Wong, 2006, p. 30). Despite building a successful retail chain in the 1990s, her business was hit by the SARS epidemic in 2003, resulting in her bankruptcy. However, we find that this story of failure was reported in an atypically positive way as she was instead portrayed as a courageous and resilient entrepreneur in the face of failure.

Compared to the earlier period whereby the traditional roles of mother and wife were highlighted, the media reported more instances of women entrepreneurs working in traditionally male-dominated fields such as computing and engineering (e.g., Leong, 2001; Yong, 2000). In line with the government’s intentions to transform Singapore into a knowledge-based economy, these women are depicted as wonder women who defied the odds and challenged gender norms. To be successful female entrepreneurs, authors admitted that women must overcome the major challenges of gender discrimination in these male-dominated fields as part of their entrepreneurial spirit of resilience and hard work.

Despite the weakening of traditional gender stereotypes alongside the emergence of new representations of women entrepreneurs, it is still implied that marriage and motherhood are the preferential life goal for women. In an article from The Straits Times on the woman-entrepreneur-cum-national-role-model Ms. Nanz Chong-Komo, the author shifts the focus from her failed business to motherhood:

Her One.99 Shop empire of 14 budget stores crumbled, she was declared bankrupt, and now both she and her husband are unemployed. But forget frowns and tears. Etched almost permanently on her face during an hour-long Sunday Times interview was a beatific smile: The reason? She has given birth to her first child, Zara Ying-Ying Komo. The radiant mother [⋯] said: “God took away those 14 ‘babies,’ but gave me this most precious one [⋯]” (Li, 2003, p. 10)

In this article, though it can be implicitly understood that marriage and motherhood may be barriers to entrepreneurship, we continuously see the portrayal of women as natural mothers. Not only does the author detail Ms. Nanz Chong-Komo’s satisfaction and happiness with being a first-time mother, but the metaphor of her failed business as babies implies that even when she was a highly accomplished entrepreneur, she was naturally a mother. The portrayal of this national heroine was thus subtly pervaded by the discourse of domesticity.

Mumpreneurs and Stay-At-Home Mothers

Eventually, strong portrayals of motherhood made a comeback in the 2010s. This is evident in the content of the articles. Table 3 summarizes the frequency of articles containing the terms “mother,” “mum (mummies),” and “wife (wives)” in both title and content. The trends show that while there is a gradual increase in interlinking women entrepreneurs with their social roles as wives and mothers in the 2000s, in the 2010s the centrality of motherhood resurfaced to re-emphasize that particular aspect of the women entrepreneurs’ identity, more than their just being wives. This shows that these gender categories carry shifting connotations depending on their purpose for national development at the time.

The emphasis on the co-existence of motherhood and entrepreneurship as mutually reinforcing rather than contradictory may be attributed to the declining birth rates, the aging population, and insufficient welfare coverage. With declining fertility rates since the 1980s (Singapore Department of Statistics, 2018, p. 29), the Singapore government has promoted motherhood by providing financial incentives for families having more children along with the entrepreneurship program spearheaded by the Research, Innovation and Enterprise Council (Cheah & Ho, 2019). The Standards, Productivity and Innovation Board (SPRING Singapore) was formed in 2002 by the Ministry of Trade and Industry to encourage enterprise development and competitiveness (Chua, 2019). Furthermore, the aging population and welfare provisions reinforce the role of mothers as the main caregivers to the elderly.

However, the discussion of motherhood in these recent articles is different from that in the 1990s. Although motherhood is emphasized, it is integrated into the entrepreneurship discourse and reframed with a new term—“mumpreneurs.” A representative article titled “Mums Mean Business” depicted mumpreneurs primarily as stay-at-home mothers who work from home rather than in a corporate setting (Azhar, 2013). Typically, authors highlight these mumpreneurs’ initial sacrifice of their high-paying and high-status positions in the corporate world because these high-flying women experienced guilt and regret for not being able to witness their children’s developmental milestones. However, authors also structure their narratives to frame entrepreneurship as the preferred alternative that facilitates work-life balance and allows for the fulfillment of personal ambition alongside the emotional satisfaction of motherhood.

The authors creatively frame entrepreneurship as a facilitator of work-life balance and a superior alternative to corporate life. It enables personal fulfillment from work and the emotional fulfillment of being a mother. As one author writes:

Mothers interviewed said they enjoy the flexibility. Instead of being shackled to a nine-to-five job, they work around their children’s schedules and can have “no work” periods. This allows them to enjoy the best of both worlds: The challenge and satisfaction that come with work and time with their children in their formative years. These businesses are not “cottage” ones helmed by the low-income housewives [⋯] Instead, they range from employment agencies and party-planning firms to those offering legal mediation or fitness classes. (Tai, 2014, p. 18)

In this instance, the author rejects the notion that home-based entrepreneurship is a cottage industry job and attempts to elevate the social status of these mumpreneurs as legitimate professionals deserving of recognition. Furthermore, many authors adopt an approving tone that celebrates these women’s choice to become entrepreneurs. They are venerated as “superwomen” (Yip, 2015) and “wonder women” (Chai, 2017) for “smashing glass ceilings” (Yip, 2016). Though the authors often emphasize the hectic lives of these women entrepreneurs in juggling the two worlds, the portrayal is generally optimistic and idealistic (e.g., Lee, 2017; Seow, 2014).

Interestingly, the authors also attempt to elevate the desirability of motherhood by highlighting the work-life integration demonstrated by mumpreneurs. Motherhood was seen as a credential, and such experiences facilitate the innovation of business ideas and a better understanding of similar consumers. The motivations and strategies of mumpreneurs, grounded in motherhood, reinforce the image that their maternal identity is of greater significance than their entrepreneurial identity. Entrepreneurship is framed as a means to fulfill the role of a good mother, and being a good mother empowers them to be effective entrepreneurs. Ultimately, this portrayal of women entrepreneurs as stay-at-home mumpreneurs reinforces the role of women as primary caregivers at home. The legitimization of “mumpreneurs” as a social category in the media further characterizes women entrepreneurs as natural “social” entrepreneurs. Women are praised for their natural instincts and emotional talents in solving community problems, helping the youth, and caring for the elderly. Again, the image of a caring mother is tightly integrated with being a woman entrepreneur.

Young Single Women as the Genderless Other

Alongside the wave of mumpreneurs, one recent development worth observing is the emergent role of young women engaged in entrepreneurship in Singapore, but in the news, these young women often appear genderless in that their coverage does not contain the terms “woman” or “female” (see Table 2). These images of single and independent women have rarely been reported upon until very recently, with more young people participating in the startup culture, and their representation in the media is usually genderless. The most notable example is Ms. Tan Hooi Ling, the co-founder of Grab, a Singapore-based ride-hailing company, whose “introverted,” “practical,” and “modest” personality are constantly noted in the media, but these news reports do not accentuate her gender (Tan, 2017).

In Tan Hooi Ling’s case, the first news item about her only appeared in 2015 as a co-founder without indicating her gender, while the entire story was about the other more outspoken male co-founder. Only later was Ms. Tan referred to as an entrepreneur along with her co-founder, but throughout the article her gender remains unknown to the reader. Given that Ms. Tan’s name could be mistaken as male, people would easily miss out on the fact that she is a female entrepreneur. This obscuring of young female entrepreneurs by de-linking them from their gender in the news media further reinforces the dominant image of the female entrepreneur as one that embraces her gender role as a mother.

Conclusion

In this first study on the media representation of women entrepreneurs in Singapore, our findings not only supplement the existing limited number of studies on the topic but also contribute to the extensive multi-disciplinary academic interest in gender and entrepreneurship. In this study, we find that the dominant categories of women entrepreneurs in Singapore are as a steel magnolia, a good mother and dutiful wife, and a mumpreneur. We further demonstrate that the meanings of these social categories for women entrepreneurs are not set in stone but change with their perceived purpose in national development. The continuous public portrayal of the work-family challenge faced by steel magnolias finally gets reconciled in the role of mumpreneur in which motherhood and entrepreneurship can be mutually reinforcing. Our findings show that while deep-rooted gender stereotypes still prevail in a society known for entrepreneurship, the meanings of dominant gender categories are not stable and often shift with national needs.

Our research also finds that news reports fail to provide diverse role models of women entrepreneurs. Considering the important role of The Business Times and The Strait Times in Singapore’s political landscape, it is reasonable to infer that the selection of these model cases represents the mainstream understanding of women entrepreneurs and even serves the critical function of conveying the state’s acceptable image of a female entrepreneur who can both contribute to economic growth as an entrepreneur and social cohesion as a mother. As we observed, an alternative image of female entrepreneur may have begun emerging in recent years given that more young people are engaged in the startup culture, but these alternative female role models are still quite rare in the mainstream media, and they often appear to be genderless (and therefore presumably male) if the news reporter does not indicate their gender. More mentorship programs recognizing the inclusiveness and diversity of experience of young people and more gender-friendly policies to support women and minorities in pursuit of entrepreneurship are much needed. Another issue is that news reports tend to capture every stage of the women’s business lifecycle in detail. It is potentially problematic and unnecessary to amplify women entrepreneurs’ failures or attribute blame to the gendered characteristics of the female’s life cycle. This may unintentionally reinforce the connection between women and their prescribed gender roles as wives and mothers.

Similar to findings in other countries such as Japan (Bobrowska & Conrad, 2017) and Germany (Achtenhagen & Welter, 2011), we also find that stereotypical gendered discourses pervade the two newspaper sources. However, unlike Japan, where women entrepreneurs are consistently placed in the category of “wife,” in Singapore, “wife” as a social category has gradually disappeared after 2000 while “mother” has regained significance in the news since 2010. Nevertheless, while Singaporean women are permitted more space in their work and business, women entrepreneurs’ public image is highly connected to motherhood or feminine qualities.

Lastly, our findings highlight the importance of the national context and the role of the government’s policy orientation in shaping women’s entrepreneurship. Though Singapore may be an extreme case where the media is tightly regulated by the government, we also note that the active involvement of the government may not always be negative. As evidenced in our study, the statement of a powerful politician can suppress and transform the previously stereotypical representations of women entrepreneurs in the early 2000s. A subsequent shift in public policy may also lead to the revival of a gendered discourse, where gender roles such as motherhood are creatively re-interpreted as a concept compatible with entrepreneurship.

References

- Achtenhagen, L., & Welter, F. (2007). Media discourse in entrepreneurship research. In H. Neergaard & J. P. Ulhøi (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative methods in entrepreneurship research (pp. 193–251). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

-

Achtenhagen, L., & Welter, F. (2011). Surfing on the ironing board: The representation of women’s entrepreneurship in German newspapers. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 23(9–10), 763–786.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2010.520338]

-

Acker, J. (1990). Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: A theory of gendered organizations. Gender & Society, 4(2), 139–158.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/089124390004002002]

- Ahl, H. (2002). The construction of the female entrepreneur as the other. In B. Czarniawska & H. Höpfl (Eds.), Casting the other: The production and maintenance of inequalities in work organizations (pp. 52–67). London, UK: Routledge.

-

Ahl, H. (2006). Why research on women entrepreneurs needs new directions. Entrepreneurship and Practice, 30(5), 595–621.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2006.00138.x]

-

Ahl, H., & Nelson, T. (2015). How policy positions women entrepreneurs: A comparative analysis of state discourse in Sweden and the United States. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(2), 273–291.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.08.002]

- Anthony, S. D. (2015, February 25). How Singapore became an entrepreneurial hub. Harvard Business Review, retrieved February 24, 2021, from https://hbr.org/2015/02/how-singapore-became-an-entrepreneurial-hub

-

Armstrong, D., Gosling, A., Weinman, J., & Marteau, T. (1997). The place of inter-rater reliability in qualitative research: An empirical study. Sociology, 31(3), 597–606.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038597031003015]

- Azhar, R. (2013, May 10). Mums mean business. The Straits Times, pp. 12–13.

-

Berglund, K., Ahl, H., Pettersson, K., & Tillmar, M. (2018). Women’s entrepreneurship, neoliberalism and economic justice in the postfeminist era: A discourse analysis of policy change in Sweden. Gender, Work & Organization, 25(5), 531–556.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12269]

-

Bobrowska, S., & Conrad, H. (2017). Discourses of female entrepreneurship in the Japanese business press: 25 years and little progress. Japanese Studies, 37(1), 1–22.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/10371397.2017.1293474]

-

Bruni, A., Gherardi, S., & Poggio, B. (2004). Doing gender, doing entrepreneurship: An ethnographic account of intertwined practices. Gender, Work & Organization, 11(4), 406–429.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2004.00240.x]

-

Byrne, J., Fattoum, S., & Garcia, M. C. D. (2019). Role models and women entrepreneurs: Entrepreneurial superwoman has her say. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(1), 154–184.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12426]

-

Bullough, A., Renko, M., & Abdelzaher, D. (2014). Women’s business ownership: Operating within the context of institutional and in-group collectivism. Journal of Management, 43(7), 2037–2064.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314561302]

- Chai, H. Y. (2017, July 8). Wonder women. The Business Times, Retrieved June 18, 2021, from https://www.businesstimes.com.sg/brunch/wonder-women

-

Cheah, S., & Ho, Y. P. (2019). Building the ecosystem for social entrepreneurship: University social enterprise cases in Singapore. Science, Technology and Society, 24(3), 507–526.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0971721819873190]

-

Chew, I. K. H., & Tan, C. Y. (1991). The changing pattern of women entrepreneurs: The Singapore experience. Women in Management Review, 6(6). doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000001804

[https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000001804]

-

Chua, E. H. C. (2019). Survival by technopreneurialism: Innovation, imaginaries and the new narrative of nationhood in Singapore. Science, Technology and Society, 24(3), 527–544.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0971721819873202]

- Chua, L. H. (1999a, February 3). S’pore lacks “quality” entrepreneurs. The Straits Times, p. 4.

- Chua, L. H. (1999b, April 10). $1.7b fund and the ability to spot winners. The Straits Times, p. 53.

- Dell. (2019). 2019 Dell Women Entrepreneur Cities Index. Retrieved June 18, 2021, from https://www.dell.com/learn/sg/en/sgcorp1/corpcomm_docs/dell-we-cities-2019-executive-summary.pdf

- Ee, J. (1997, November 13). Tough entrepreneur, caring boss. The Business Times, p. 14.

-

George, C. (2007). Consolidating authoritarian rule: Calibrated coercion in Singapore. The Pacific Review, 20(2), 127–145.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/09512740701306782]

-

Giménez, D., & Calabrò, A. (2018). The salient role of institutions in women’s entrepreneurship: A critical review and agenda for future research. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 14(4), 857–882.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-017-0480-5]

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Piscataway, NJ: Aldine Transaction.

- General Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM). (2014). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2014 Global Report. Retrieved August 15, 2019, from https://www.gemconsortium.org/report/49079/

- Guan, L. B. (1992, June 3). Gritty publisher. The Straits Times, p. 11.

-

Hamilton, E. (2013). The discourse of entrepreneurial masculinities (and femininities). Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 25(1–2), 90–99.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2012.746879]

-

Henry, C., Foss, L., & Ahl, H. (2016). Gender and entrepreneurship research: A review of methodological approaches. International Small Business Journal, 34(3), 217–241.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242614549779]

- Ho, S. B. (1994, April 3). It’s a husband and wife team. The Straits Times, p. 3.

-

Jennings, J. E., & Brush, C. D. (2013). Research on women entrepreneurs: Challenges to (and from) the broader entrepreneurship literature? The Academy of Management Annals, 7(1), 663–715.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2013.782190]

- Koh, V. (1998, December 6). Steel magnolias. The Straits Times, p. 16.

- Koh, V. (1999, November 19). Be strong, focused and determined. The Straits Times, p. 25.

-

Lee, J. (1996). The motivation of women entrepreneurs in Singapore. Women in Management Review, 11(2), 18–29.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/09649429610112574]

- Lee, J. (2005). Women entrepreneurs in Singapore. In S. L. Fielden & M. J. Davidson (Eds.), International handbook of Women and Small Business Entrepreneurship (pp. 178–192). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Lee, M. (2017, September 18). Hectic life of a mumpreneur. The Straits Times, Retrieved 18 June, 2021, from https://www.straitstimes.com/business/hectic-life-of-a-mumpreneur

-

Lee, J. S. K., & Choo, S. L. (2001). Work-family conflict of women entrepreneurs in Singapore. Women in Management Review, 16(5/6), 204–221.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/09649420110395692]

- Leong, C. T. (2001, February 11). From small-town orphan to big boss. The Straits Times, p. 30.

- Li, X. Y. (2003, December 7). Ex-boss of One.99 shop is bankrupt but⋯ She’s all smiles. The Straits Times, p. 10.

- Lim, C. (1991, July 8). Perseverance and commitment. The Business Times, p. 13.

- Lim, S. T. (1990, August 3). Hour glass woman made of steel. The Straits Times, p. 9.

- Long, S. (1999, February 14). The earth mother. The Straits Times, p. 9.

-

Marlow, S. (2002). Women and self-employment: A part of or apart from theoretical construct? The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 3(2), 83–91.

[https://doi.org/10.5367/000000002101299088]

-

Marlow, S., & Swail, J. (2014). Gender, risk and finance: Why can’t a woman be more like a man? Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 26(1–2), 80–96.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2013.860484]

- Mastercard. (2018). Mastercard index of women entrepreneurs 2018. Retrieved February 26, 2020, from https://newsroom.mastercard.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/MIWE_2018_Final_Report.pdf

- Maysami, R. C., & Goby, V. P. (1999). Female business owners in Singapore and elsewhere: A review of studies. Journal of Small Business Management, 37(2), 96–105.

-

Mirchandani, K. (1999). Feminist insight on gendered work: New directions in research on women and entrepreneurship. Gender, Work and Organisation, 6(4), 224–235.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0432.00085]

-

Neuendorf, K. A. (2017). The content analysis guidebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

[https://doi.org/10.4135/9781071802878]

-

O’Connor, C., & Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1–13.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919899220]

- Orlandi, L. B. (2017). Am I an entrepreneur? Identity struggle in the contemporary women entrepreneurship discourse. Contemporary Economics, 11(4), 487–498.

-

Radu, M., & Redien-Collot, R. (2008). The social representation of entrepreneurs in the French press: Desirable and feasible models? International Small Business Journal, 26(3), 259–298.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242608088739]

-

Rajah, J. (2012). Authoritarian rule of law: Legislation, discourse and legitimacy in Singapore. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511998201]

- Reuters. (1984, Feb 12). Singapore is urging the educated to multiply. The New York Times. Retrieved April 30, 2021, from https://www.nytimes.com/1984/02/12/world/singapore-is-urging-the-educated-to-multiply.html

-

Santos, G., Marques, C. S., & Ferreira, J. J. (2018). A look back over the past 40 years of female entrepreneurship: Mapping knowledge networks. Scientometrics, 115(2), 953–987.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2705-y]

-

Seet, P. S., Ahmad, N. H., & Seet, L. C. (2008). Singapore’s female entrepreneurs. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 5(3/4), 257–271.

[https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2008.017303]

- Seow, J. (2014, July 21). “Mumpreneurs” on the rise in bid for work-life balance. The Straits Times, Retrieved June 18, 2021, from https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/mumpreneurs-on-the-rise-in-bid-for-work-life-balance

- Sequeira, J. M., Wang, Z., & Peyrefitte, J. (2016). Challenges to new venture creation and paths to venture success: Stories from Japanese and Chinese women entrepreneurs. The Journal of Business Diversity, 16(1), 42–59.

- Shome, T. (2006). State-guided entrepreneurship: A case study. (Department of Management and International Business Research Working Paper Series 2006, no. 4). Auckland, NZ: Massey University, Department of Management and International Business.

- Singapore Department of Statistics. (2018). Population trends. Government of Singapore.

- Singapore Government. (1999, November 19). Speech by Dr. Aline Wong, Senior Minister of State for Education, at the 2nd SME Day CUM ASME-HP Woman Entrepreneur of the Year Award Presentation. Retrieved February 22, 2021, from https://www.nas.gov.sg/archivesonline/data/pdfdoc/1999111903/aw19991119g.pdf

- Software wizard wins Rotary award (1989, June 15), The Business Times, p. 3.

- Soh, F. (1995, August 20). Chan Mei Lin returns to her Asian roots. The Straits Times, p. 7.

-

Stead, V. (2017). Belonging and women entrepreneurs: Women’s navigation of gendered assumptions in entrepreneurial practice. International Small Business Journal, 35(1), 61–77.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242615594413]

- Subramony, V. (1989, June 25). Against all odds. The Straits Times, p. 10.

- Tai, J. (2014, March 1). More mums setting up home businesses. The Straits Times, p. 18.

- Tan, S. (2017, July 16). Lunch with Sumiko: Grab whiz Tan Hooi Ling happy to stay low-key. The Strait Times. Retrieved June 18, 2021, from https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/grab-whiz-happy-to-stay-low-key

- Tee, H. C. (1999, August 15). TIME to do business. The Straits Times, p. 2.

- Teo, S. K. (1996). Women entrepreneurs of Singapore. In A. M. Low & W. L. Tan (Eds.), Entrepreneurs, Entrepreneurship and Enterprising Culture (pp. 254–289). Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley.

-

Weber, R. (1990). Basic content analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

[https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412983488]

-

Welter, F. (2020). Contexts and gender—looking back and thinking forward. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 12(1), 27–38.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/IJGE-04-2019-0082]

- Wong, K. H. (2006, March 26). Success in failure. The Straits Times, p. 30.

-

Yang, T., & Aldrich, H. E. (2014). Who’s the boss? Explaining gender inequality in entrepreneurial teams. American Sociological Review, 79(2), 303–327.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122414524207]

- Yip, M. (2015, May 9). Mothers know best. The Business Times, 2–3.

- Yip, M. (2016, March 12). Bibs & bytes. The Business Times, Retrieved June 18, 2021, from https://www.businesstimes.com.sg/lifestyle/style/bibs-bytes

- Yong, A. (2000, June 24). Woman technopreneur wins annual youth award. The Straits Times, p. 60.

Biographical Note: Ling Han (corresponding author) is an Assistant Professor in the Gender Studies Programme in the Chinese University of Hong Kong. She was previously a research fellow at the Asia Centre for Social Entrepreneurship and Philanthropy at the NUS Business School. She is a sociologist researching on gender, technology, entrepreneurship, and social innovation. Email: linghan@cuhk.edu.hk

Biographical Note: Chengpang Lee is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Applied Social Sciences in the Hong Kong Polytechnic University. He studies knowledge communities and organizational change. Email: leecp1223@gmail.com

Biographical Note: Gracia Jieyi Lee is a student in the MA Program in the Social Sciences at the University of Chicago and was the research assistant for this project. Email: gracialjy@gmail.com