Pregnancy-Related Health Information-Seeking Behavior of Rural Women of Selected Villages of North India

Abstract

Maternal health improvement is one of the main targets of India's national health programs; however, maternal mortality reduction has not yet reached satisfactory levels. Maternal health outcomes depend on the health literacy of pregnant women. The exploration of areas in which women seek information can help in a better understanding of their health information needs. A cross-sectional study assessed health information-seeking behavior during pregnancy, health information resources used, and related barriers perceived by rural women in North India. Rural women who were pregnant or had a live birth in the past six months (N=100) were selected using purposive sampling techniques from five selected villages in the Patiala district of Punjab state, India. The majority were aged 26–30 years and reported dependence on their husbands and family members in choosing sources of health information. They reported doctors, nurses, and the Internet as valuable resources for seeking health information during pregnancy. The essential topics on which women seek information are fetal growth, delivery setting, body changes during pregnancy, and other related concerns. Women reported the significant barriers to important health information as long queues and inconvenient service hours during antenatal check-ups in health settings. The findings of the study point toward the need for strengthening and improving the existing services for availability of verified and reliable information, education and communication (IEC) resources, and maternal services in the public health sector.

Keywords:

health information-seeking behavior, pregnant women, rural population, information seeking behavior, health literacyIntroduction

Pregnancy is a crucial period in a woman’s life. One of the significant contributors to the disease burden in India is the high rates of maternal and infant mortality (World Health Organization, 2019). Despite a gradual improvement in health indicators, a reduction in maternal and child-related morbidities is required (Hill et al., 2007). In India, the Reproductive, Maternal, New-born, Child, and Adolescent Health (RMNCH+A) framework was adopted in 2013, and maternal mortality has decreased tremendously, but India’s maternal mortality rate is still higher than that of developed countries. The primary factors responsible for maternal and child health morbidity and mortality are insufficient utilization of resources, access, and promotion of health information (Vora et al., 2009).

Every year, nearly 28 million women in India experience pregnancy and there are 26 million live births (Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Govt. of India, 2010). Pregnancy is associated with multiple complex and interrelated physical and psychological changes that occur in women’s lives, such as diet, nutritional requirements, physical activity, sexual life, complications, precautions, and warning signs. Knowledge regarding such aspects of pregnancy and the availability of resources to provide knowledge are crucial for a woman and her baby. Promoting optimal health care and support is essential for the public health sector. The World Health Organization recommends quality health care and women empowerment and education to reduce maternal mortality and improve pregnancy experience and a particular focus on rural women and universal health coverage has been emphasized (World Health Organization, 2019). Maternal mortality is related to the self-care abilities and knowledge of pregnant women, which is further related to the type of health information available to women (Viau, Padula, & Eddy, 2002).

Providing timely and appropriate maternal care and services can potentially moderate these disparities. Research findings from multiple studies conducted in developing countries have indicated that pregnancy-related information is positively associated with better health outcomes in low-income women (Darmstadt et al., 2005; Hong & Ruiz-Beltran, 2007). In addition, a study by Singh, Newburn, Smith, and Wiggins (2002) reported the greatest desire for health information among women from low socioeconomic backgrounds. This desire to seek information indicates positive behavior associated with compliance and adherence to regimens, resulting in better clinical outcomes (Matthews, Sellergren, Manfredi, & Williams, 2002). Women from rural areas are generally illiterate and less likely to use primary healthcare (Registrar General of India, 2006). In India, despite the availability of health information resources and other benefits, a high percentage of rural women face severe health disparities (Ramanadhan & Viswanath, 2006). This issue can be attributed to a lack of access to such resources, inadequate decision-making ability, poor access to emergency and obstetrical services, and barriers such as long distances and sub-standard and scarce transportation services during pregnancy. Furthermore, previous literature has reported that maternal mortality among low-income women is linked to direct obstetric causes and little or no knowledge regarding obstetric complications (Das & Sarkar, 2014). Rural women face many challenges, such as difficulty in distinguishing between reliable information and misinformation, insufficient interaction between women and healthcare providers, poor accessibility to needed resources, lack of information related to common complications in pregnancy, and stress or anxiety related to pregnancy-related issues (Javanmardi, Noroozi, Mostafavi, & Ashrafi-rizi, 2019).

The health-seeking behaviors and needs of women have been studied extensively, but there is a scarcity of studies related to the health information-seeking behaviors of pregnant women. Concerning women’s healthcare needs, a study by Robinson et al. (2018) determined the consumer health-related needs among pregnant women and caregivers in Vanderbilt University Medical Centre, USA. Surveys and semi-structured interviews were conducted with 71 pregnant women and 29 caregivers from advanced maternal-fetal and group prenatal care settings and 1054 health-related needs were reported, including informational (66.2% of respondents), logistical (15.9%), social (8.9%), and medical (86%). These needs were categorized as met (24%), partially met (49%), or not met (28%) and the unmet needs of caregivers and pregnant women were different, requiring separate resources for each group (Robinson et al., 2018).

Another descriptive study conducted in the antenatal clinic of the Jaffna Teaching Hospital, Sri Lanka, used an interviewer-administered questionnaire to assess information needs, information-seeking behavior, and barriers among 400 pregnant women. Of the study participants, 61% reported information-seeking from various sources, led by family members and friends (63%). Of 20 types of information related to pregnancy and childbirth, pregnancy complications (56%), delivery complications (54%), methods of child delivery (52%), and special tests required during pregnancy (48%) were most in demand. The unavailability of resources has been reported as the primary barrier to assessing health information. The chi-square test was used for inferential statistics showing the association between information sources and other variables and this revealed that age and educational status are significantly associated (Murugathas, Sritharan, & Santharooban, 2020). At the same time, another study conducted by Onuoha and Amuda (2013) in Nigeria reported that pregnant women mainly sought information on environmental cleanliness, immunization, prevention and management of diseases, personal care, and care of the baby. Doctors and nurses were the main sources of information available, and the main challenges reported by women were lack of libraries, low-income status, and lack of time, followed by higher costs of communication and non-availability of qualified health professionals (Onuoha & Amuda, 2013).

In an era with high availability of online media platforms such as websites, mobile apps, instant messaging, and many more, pregnancy-related health information-seeking behavior was assessed along with the impact of social media in a qualitative study conducted on 20 expectant mothers in China. Pregnancy-related health services delivered via social media channels were also explored. All participants were interviewed and reported using social media for information related to pregnancy with thematic analysis revealing four themes: gravida, fetus, delivery, and postpartum. Pregnancy-related taboos, fetal development, preparation for delivery, and infant care were mentioned by the majority of participants for each of the themes respectively (Zhu, Zeng, Zhang, Evans, & He, 2019).

There are few studies on health information seeking, whereas several studies have been conducted on health-seeking behavior. In developing countries, especially in rural areas, pregnant women face challenges in obtaining correct information owing to limited access to healthcare services and insufficient healthcare workforce availability. Thus, this research was conducted with the following objectives: 1. to assess and determine health information-seeking behaviors regarding pregnancy; and 2. to assess the health information resources used and the related barriers as perceived by rural women.

Methods

Research Design and Sampling

A cross-sectional design was used to assess health information-seeking behavior regarding pregnancy among rural women (N=100) who were pregnant or had had a live birth in the past six months. Rural women were operationally defined as women residing in villages in Punjab state, India. Rural women from five selected villages (total population 5232) in Punjab State, India, who attended primary healthcare centers (PHCs) for regular health check-ups were selected using purposive sampling techniques. The sample size was calculated using the formula N=4pq/I2, where p = prevalence proportion, q = p-1, and I = acceptable error (5%-20% of p). A previous study on pregnancy-related health information-seeking reported 61% of women sought health information related to pregnancy (Murugathas et al., 2020). Therefore, we took p = 61%, q = p-1 = 39%, and I (i.e. acceptable error) as 20% of p. The sample size calculated using this formula was 64. In this study a total of 100 women were selected.

Data Collection

A self-structured health information-seeking questionnaire based on the findings of previous studies (Kamali, Ahmadian, Khajouei, & Bahaadinbeigy, 2018; Merrell, 2016) consisting of a questionnaire and checklist was used for data collection after validation by a team of five experts. Section A of the instrument consisted of questions on demographics and general information. Section B included four headings: resources women used, how much trust they had in these resources, how valuable they thought resources are to them, and pregnancy-related issues for which they wanted to seek the information. Section C consisted of a checklist to collect information on the challenges faced while seeking information regarding pregnancy, including items on personal barriers, mass media barriers, geographical barriers, institutional barriers, and social barriers. Based on the number of resources used by pregnant women, three categories were formed based on the following criteria: Poor (utilization of fewer than five resources); Average (utilization of between five and nine resources); and Good (utilization of more than nine resources). The instrument's content validity was assessed by experts in community and public health; based on the agreement of all experts, it was found to be 0.82, which is considered as demonstrating excellent content validity (Shi, Mo, & Sun, 2012).

Administrative permission to conduct the study was obtained from the Sarpanches/heads of the selected villages. After approval, home visits were conducted to obtain individual consent from the subjects, and interviews were conducted using a structured tool on health information-seeking behavior regarding pregnancy. Confidentiality was maintained throughout. The data were analyzed using SPSS version 23.0.

Results

Demographic Characteristics of Subjects

The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. This shows that 49% were aged 26–30, and the overwhelming majority (98%) were married. Most (91%) were educated, 65% were homemakers, and 58% had an average family income of 10,001–20,000/month. Most (58%) were dependent on their husbands as the primary source for maternity care service payments, while 24% were self-paying. Fifty-two percent were multigravida, and 13% reported a history of miscarriages, while 48% were living in a nuclear family, followed by 37% in a joint family.

Health Information-seeking Behavior

Sixty-five out of 100 women inquired about their own health information regarding pregnancy. Only 24% of women took decisions about seeking health information by themselves, with the remainder reporting dependence on husbands (47%) or family (29%). The majority (63%) implemented what they learned directly after finding the information, and 37% reported verifying the information through more than one source on the Internet. Only 33% went for health check-ups on their own, whereas 55% received a check-up whenever the doctors called, and the remaining 12% had health check-ups only when they felt the need. While 65% reported seeking the health information only after conception, 35% reported seeking information before pregnancy. Forty-six percent of women reported getting information about health checkups from family members, 39% of them knew it before marriage, and 15% came to know about it from health workers/physicians (see Table 2).

Health Information Resources Used & Perceived Value of Different Resources

Information on the health information resources used and perceived value of different resources is presented in Table 3. Doctors (100%) were the highest used resource in the interpersonal category, and television (81%) in the mass media category. However, many women (68%) also reported getting information from newspapers, while 87% mentioned the using Internet resources during pregnancy.

When asked about the value of different resources, all cited doctors as the most valuable resource for health information, followed by nurses, reported by 82%. Among mass media resources, radio (92%) and magazines (89%) were regarded as resources of little or no value. Among other resources, 46% considered the Internet as a somewhat valuable resource, while 44% saw it as the most valuable.

Trust in Resources

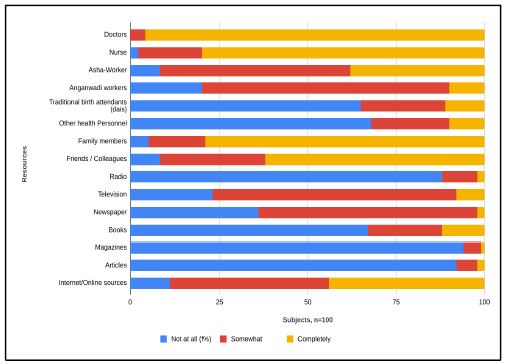

When asked about the trustworthiness of resources, 96% reported absolute trust in doctors, followed by nurses (80%). For mass media resources, the majority did not trust the information given in magazines (94%) or radio (88%). Furthermore, 68% of women reported the Internet as a trustworthy source of information (Figure 1).

Knowledge-related Areas

Table 4 shows the frequency and percentage distribution of the areas in which women generally seek knowledge about pregnancy- and childbirth-related issues. Information regarding baby growth and the availability of alternative birth settings was sought by 97%, while 93% or more reported seeking information regarding body changes during pregnancy, type of delivery, choice of hospital during pregnancy and for delivery, medications taken during pregnancy, how to pay for pregnancy, and childbirth-related expenses. On the other hand, low numbers were observed in areas like drinking caffeine during pregnancy (27%), alcohol consumption during pregnancy (20%), smoking during pregnancy (20%), and sexual intercourse during pregnancy (7%). Ranking according to the reported knowledge-related areas for seeking health information during pregnancy is shown in Table 4.

The Barriers Faced while Seeking Health Information

Women reported multiple barriers under five categories—personal, mass media, geographical, institutional, and social—while seeking health information (Table 5). They reported that a lack of time (40%) and feeling shy or scared to ask questions (29%) were significant personal barriers. Furthermore, the non-availability of libraries (78%), magazines (40%), and books (36%) were also reported as significant mass media barriers. Between 23% and 25% of women reported transportation unavailability, bumpy roads, and clinics very far from home as geographical barriers. No significant social barriers to seeking health information were reported, with only neglect of household responsibilities (17%) and family pressure (6%) being cited as factors.

Association between Selected Demographic Variables and Utilization of Available Resources

The association between the utilization of available resources and selected sociodemographic variables was analyzed using the chi-square test, as shown in Table 6. Based on the number of available resources used, three categories were established (as mentioned earlier): Poor (utilization of fewer than five resources), Average (utilization of five to nine resources), and Good (utilization of more than nine resources). Among all the selected sociodemographic variables, only age (p=0.01) and the primary payment source for all maternity care services (p=0.04) were significantly associated with the availability of resources. Furthermore, women aged 26–33 reported average use of resources. As age increased, resource utilization declined. Other variables such as religion, educational status, marital status, employment status, family income, obstetrical history, type of family, and comorbidities were not significantly associated with utilizing available resources (p > 0.04).

Discussion

In the present study, we found that most women inquired about health information regarding pregnancy by themselves. Furthermore, they reported that the decision on seeking health information was primarily undertaken by their husbands, and then more-or-less equally by the women themselves or by family members. This is explained by the fact that the majority of rural women in this study were not employed and were dependent on their husbands and family for financial support. Similar findings were reported from another study (White et al., 2006) where 94% of rural women assessed for health-seeking behavior reported their husband/male partner as the primary decision-maker.

Previous studies have reported that doctors are the most used resource of information (Almoajel & Almarqabi, 2016; Onuoha & Amuda, 2013). These findings are consistent with our study results, where all women (100%) graded doctors as the highest used resource. The Internet has also been a leading resource in today's tech-savvy world, as 87% of subjects reported the Internet as a readily available and used resource, and only 20% considered it to be of no value. A study at the University of Florida supports this finding; in that study, the health information sources reported were the use of search engines (75.6%), discussion forums (53.6%), video sites (23.8%), social news sites (17.9%), microblogs (20.2%), Facebook groups (22.6%), and other social sites (4.8%) (Merrell, 2016). When using the Internet for health-related information, the need for accurate and verified information for pregnant women is evident. Women must be educated not to blindly trust Internet sources but to verify the data with health professionals such as doctors, midwives, and nurses.

Kamali et al. (2018) observed the various areas the subjects reported seeking information from. These included information about intrapartum care (86%), postpartum physical and psychological complications (83%), fetal growth and development (82.5%), nutrition (82%), and pregnancy-related testing (81.5%) (Kamali et al., 2018). Similar areas of knowledge were reported in the present study, with the majority of women seeking information on pregnancy-related concerns. However, one limitation of this study is that it did not consider knowledge areas related to postnatal periods—previous studies have reported women seeking information about immunization, family planning, and environmental cleanliness during this period (Onuoha & Amuda, 2013).

One-fourth of the women reported geographical barriers, such as dispensaries being too far from their home, followed by no transportation to take them to the health dispensary. The same was experienced by subjects in another study who reported transport as a barrier in seeking information (Vincent et al., 2017). These findings highlight the need to strengthen maternal healthcare services, including information, education, and communication (IEC) services and transportation facilities in rural areas.

Another limitation of our study is that it was confined to a small geographical area in northern India. It is recommended that similar studies be conducted with a larger sample size in other regions of India, especially in remote or undeveloped rural areas with low resource availability of maternal health services. The findings of this study can form the basis for strengthening and improving existing policies, the availability of information, education and communication (IEC) resources, and maternal services in the public health sector.

Conclusion

Pregnancy is the most critical period in a woman's life, but also a distressing period due to the number of changes taking place in her body. Pregnant women seek information from sources such as healthcare professionals, the Internet, books, and magazines and the most crucial concern is the accuracy of the information received. Women find doctors and nurses to be the most available and valuable resources for seeking health information during pregnancy, followed by other resources. Therefore, the findings of the present study emphasize that health professionals must provide opportunities for women to ask questions regarding their pregnancy-related concerns during each antenatal visit. Furthermore, health education about self-care during pregnancy must be an essential part of antenatal care at the primary health institution level.

References

-

Almoajel, A., & Almarqabi, N. (2016). Online health-information seeking behavior among pregnant women in prenatal clinics at King Saud Medical City, Riyadh. Journal of Womens Health, Issues and Care, 3, 2.

[https://doi.org/10.4172/2325-9795.1000228]

-

Darmstadt, G. L., Bhutta, Z. A., Cousens, S., Adam, T., Walker, N., De Bernis, L., & Lancet Neonatal Survival Steering Team. (2005). Evidence-based, cost-effective interventions: How many newborn babies can we save? The Lancet, 365(9463), 977–988.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71088-6]

- Das, A., & Sarkar, M. (2014). Pregnancy-related health information-seeking behaviors among rural pregnant women in India: Validating the Wilson Model in the Indian context. The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 87(3), 251–262.

-

Hill, K., Thomas, K., AbouZahr, C., Walker, N., Say, L., Inoue, M., . . . Maternal Mortality Working Group. (2007). Estimates of maternal mortality worldwide between 1990 and 2005: An assessment of available data. The Lancet, 370(9595), 1311–1319.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61572-4]

-

Hong, R., & Ruiz-Beltran, M. (2007). Impact of prenatal care on infant survival in Bangladesh. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 11(2), 199–206.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-006-0147-2]

-

Javanmardi, M., Noroozi, M., Mostafavi, F., & Ashrafi-rizi, H. (2019). Challenges to access health information during pregnancy in Iran: A qualitative study from the perspective of pregnant women, midwives and obstetricians. Reproductive Health, 16(1), 1-7.

[https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-019-0789-3]

-

Kamali, S., Ahmadian, L., Khajouei, R., & Bahaadinbeigy, K. (2018). Health information needs of pregnant women: Information sources, motives and barriers. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 35(1), 24–37.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/hir.12200]

-

Matthews, A. K., Sellergren, S. A., Manfredi, C., & Williams, M. (2002). Factors influencing medical information seeking among African American cancer patients. Journal of Health Communication, 7(3), 205–219.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730290088094]

- Merrell, L. K. (2016). Exploration of the pregnancy-related health information seeking behavior of women who gave birth in the past year. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 77(9-B(E)). Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/etd/6116

- Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Govt. of India. (2010). Maternal death review guidebook. New Delhi, India: Government of India.

-

Murugathas, K., Sritharan, T., & Santharooban, S. (2020). Health information needs and information seeking behavior of pregnant women attending antenatal clinics of Jaffna Teaching Hospital. Journal of the University Librarians Association of Sri Lanka, 23(1), 73-90.

[https://doi.org/10.4038/jula.v23i1.7967]

- Onuoha, U. D., & Amuda, A. A. (2013). Information seeking behaviour of pregnant women in selected hospitals of Ibadan Metropolis. Information Impact: Journal of Information and Knowledge Management, 4(1), 76–91.

-

Ramanadhan, S., & Viswanath, K. (2006). Health and the information nonseeker: A profile. Health Communication, 20(2), 131–139.

[https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327027hc2002_4]

- Registrar General of India. (2006). Sample registration system maternal mortality in India: 1997-2003 trends, causes and risk factors. New Delhi, India: Government of India. Retrieved from http://www.cghr.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/RGI-CGHR-Maternal-Mortality-in-India-1997–2003.pdf

-

Robinson, J. R., Anders, S. H., Novak, L. L., Simpson, C. L., Holroyd, L. E., Bennett, K. A., & Jackson, G. P. (2018). Consumer health-related needs of pregnant women and their caregivers. JAMIA Open, 1(1).

[https://doi.org/10.1093/jamiaopen/ooy018]

-

Shi, J., Mo, X., & Sun, Z. (2012). Zhong nan da xue bao [Content validity index in scale development]. Yi xue ban [Journal of Central South University: Medical Sciences], 37(2), 152–155.

[https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1672-7347.2012.02.007]

-

Singh, D., Newburn, M., Smith, N., & Wiggins, M. (2002). The information needs of first-time pregnant mothers. British Journal of Midwifery, 10(1), 54–58.

[https://doi.org/10.12968/bjom.2002.10.1.10054]

-

Viau, P. A., Padula, C. A., & Eddy, B. (2002). An exploration of health concerns & health-promotion behaviors in pregnant women over age 35. MCN The American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing, 27(6), 328–334.

[https://doi.org/10.1097/00005721-200211000-00006]

-

Vincent, A., Keerthana, K., Damotharan, K., Newtonraj, A., Bazroy, J., & Manikandan, M. (2017). Health care seeking behaviour of women during pregnancy in rural south India: A qualitative study. International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health, 4(10), 3636.

[https://doi.org/10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20174224]

-

Vora, K. S., Mavalankar, D. V., Ramani, K., Upadhyaya, M., Sharma, B., Iyengar, S., . . . Iyengar, K. (2009). Maternal health situation in India: A case study. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition, 27(2).

[https://doi.org/10.3329/jhpn.v27i2.3363]

-

White, K., Small, M., Frederic, R., Joseph, G., Bateau, R., & Kershaw, T. (2006). Health seeking behavior among pregnant women in rural Haiti. Health Care for Women International, 27(9), 822–838.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/07399330600880384]

- World Health Organization. (2019). Trends in maternal mortality, 2000 to 2017: Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group, & The United Nations Population Division. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/ handle/ 10665/327595

-

Zhu, C., Zeng, R., Zhang, W., Evans, R., & He, R. (2019). Pregnancy-related information seeking and sharing in the social media era among expectant mothers: Qualitative study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(12).

[https://doi.org/10.2196/13694]

Biographical Note: Harmeet Kaur Kang, Ph.D., (Corresponding Author) is Professor at Chitkara School of Health Sciences, Chitkara University, Punjab, India. She has worked in collaboration with National & International experts and has 28 research publications in her name. Her research interests include cardiovascular disease prevention and management, public health & women’s health. Email: harmeet.kaur@chitkara.edu.in.

Biographical Note: Arshdeep Kaur, Bsc. Nursing (Basic), is a Nursing Tutor at the Chitkara School of Health Sciences, Chitkara University, Punjab, India. She is a young nursing professional with clinical and academic experience. Her research interests include public health & women’s health. Email: arshdeep.k@chitkara.edu.in.

Biographical Note: Shania Saini, Bsc. Nursing (Basic) Student, Chitkara School of Health Sciences, Chitkara University, Punjab, India. Her research interests include public health & women’s health. Email: shania.saini5@gmail.com

Biographical Note: Rayees Ahmad Wani, Bsc. Nursing (Basic) Student, Chitkara School of Health Sciences, Chitkara University, Punjab, India. His research interests include public health & women’s health. Email: rayeeswani4152@gmail.com

Biographical Note: Shubhleen Kaur, Bsc. Nursing (Basic) Student, Chitkara School of Health Sciences, Chitkara University, Punjab, India. Her research interests include public health & women’s health. Email: shubchahal247@gmail.com