A Comparison between Conservative Welfare States and Korean Childcare Policy, 1993-2003

This paper analyzes family policies in the conservative welfare states and compares them with those in Korea, with specific foci on defamilization and familization policies. The time frame for the analysis is between the 1990s and early 2000s, the period identified as the beginning of an active response toward the new social risk in the conservative welfare states. Through a comparative analysis in family policies between conservative welfare states and Korea, several noticeable results were found. First, contrary to general expectation, no similarities among conservative welfare states were noted in the realm of childcare policy. Second, although family policies in conservative welfare states have been changing continuously in the last ten years, no qualitative changes were found except in France. Third, Korean childcare policy may seem to share major characteristics with conservative welfare states in rhetoric, but the actual policy differs substantially from those in the conservative states.

Keywords:

childcare policy, family policy, conservative welfare states, defamilization, familization, KoreaIntroduction

The expansion of welfare in Korea began in 1997 after the economic crisis. Social insurance such as national pension and employment insurance bore a universal right, and public assistance was institutionalized as a social right. Despite the expansion, welfare in people's lives rarely showed a marked improvement. Although controversial, it is evident that this phenomenon is related to the so-called expansion of new social risks. Decline in birth rate and increased inequality and poverty due to care crisis and labor market flexibility are the new social risks faced by current Korean society.

There is no consensus regarding the definition of the new social risks. Discussions to date are made in regard to a childcare policy realm that includes caregiving within the household (e. g., children) and the labor market participation of women with children (Taylor-Gooby, 2004). In fact, women's participation in the labor market has become a necessity for Korean families' economic stability. This is well manifested in the trend that single male breadwinner households are more likely to fall into poverty compared to dual breadwinner households, similar to western welfare states. Nevertheless, the provision of balancing work and family life (e. g., socialization of childcare) that can facilitate female participation in the labor market is not enough. In addition, regardless of women's labor market participation, care responsibility is still mainly imposed on women. Korea, which expanded its welfare around social risks based mainly on male breadwinners, is now expected to respond to the emerging new social risks.

What might be a possible solution? Many consider the social democratic care policy as the alternative form of family policy (Anttonen, 2006; Rauch, 2007). However, under the circumstances of labor market flexibility and changes in families, measures taken by Northern European welfare states more than three decades ago fail to serve as an alternative. In fact, the new social risks, with its emphasis on balancing work and family life, has already become an old social risk in the northern European social democratic welfare states (Timonen, 2004). The liberal measures represented by the United States are also not a viable alternative since the types and quality of childcare differ between families according to their economic status. The goal of a childcare policy does not rely merely on socialization of care work. The goal should be to provide socially acceptable care to every child regardless of his or her family's socioeconomic status.

A possible solution can be sought in the conservative welfare states. Characterized by women's low labor market participation rate and underdevelopment of social services, conservative welfare states resemble the new social risks faced by the Korean society. In addition, a strong social belief held by the Korean society that imposes childcare responsibilities on families (mainly women) serves as a potent ground for discussing similarities in childcare policy between Korea and conservative welfare states. Furthermore, experiences of the conservative welfare states, acknowledging market instability and attempting to mitigate the market failure (Esping-Andersen, 1990), may cast meaningful implications for the current Korean family policy (i. e., childcare policy).

With these questions in mind, we intend to analyze family policies in the conservative welfare states and compare those with Korea, with specific foci on defamilization and familization policies. The time frame for the analysis is between the 1990s and early 2000s, the period identified as the beginning of an active response toward the new social risk by the conservative welfare states. First, a conceptual framework for the analysis will be examined, followed by the research methods. Findings will be presented in two parts: a description of conservative welfare states and Korean childcare policy characteristics, and results from the multidimentional scaling and cluster analysis. The paper will conclude with a discussion.

Major Issues in the Analyses

A Debate on Core Concepts

Claus Offe (1972, cited in Knijn & Ostner, 2002) was among the first to conceptualize commodification and decommodification based on Polany's concept. Offe pointed out that the unequal power relationship between the labor force and capital triggered the need for state-led decommodification. Based on this concept, Esping-Andersen (1990, p. 37) defined decommodification as “the degree to which individuals or families can uphold a socially acceptable standard of living independently of market participation.” Despite various critiques, the concept of decommodification seems to be a useful tool to explain the pre-1980s welfare state characterized by the prevalence of male breadwinner households and the stability of male status in the labor market. However, in current conditions where the male breadwinner's status is being threatened, skepticism arises in its ability to explain and classify welfare states that do not take into account the relationship with unpaid work.

The stability of the male breadwinner in the labor market was a precondition for the welfare state to concentrate its efforts on the decommodification of male breadwinners. Industry based on semi-skilled manufacturing guaranteed the stable employment and wage for male breadwinners, and the decommodification of women was secured by male breadwinners (Knijin & Ostner, 2002, p. 148). However, the weakening of male status as main breadwinners resulting from labor market flexibility and the increase in the need for female labor market participation called for an unprecedented role of the welfare state. It is at this very point that the concept of defamilization emerged, which linked unpaid work and the role of welfare states.

Esping-Andersen (1999) acknowledged the importance of unpaid work in his classification and suggested defamilization as one of the criteria for welfare state classification. According to Esping-Andersen (1999), defamilization refers to the degree to which households' welfare and caring responsibilities are relaxed-either via welfare state provision, or via market provision (p. 51). Esping-Andersen's definition of defamilization discusses defamilization as a precondition for a person's (specifically women's) decommodification. That is, because women hold the traditional care responsibilities within the family, these responsibilities need to be relieved in order to include women in the concept of decommodification. Only then could women be commodified in the labor market, and thus be subjected to decommodification. Esping-Andersen's discussion of defamilization is expected to play a role in including women in the discussion of welfare states based on decommodification. It is a meaningful advancement that Esping-Andersen included unpaid work in the welfare state analysis.

His explanation of defamilization, however, includes a marked limitation. The major criticism lies in the argument that he does not recognize defamilization and decommodification to hold an equal status. Esping-Andersen does not consider the independent social value of unpaid work (care work) in his discussion of defamilization. In other words, he is less concerned about the provision of appropriate level of care after defamilization to those family members in need.2 This is contradictory to his discussion of decommodification. Whereas decommodification is defined as assuring an appropriate level of income despite no paid work, the definition of defamilization does not entail a provision of care to members in need when care is not available by the traditional care provider. Significance is only ascribed to lessening the care responsibilities of the traditional care providers.

If so, how should defamilization be redefined as an independent concept? If we agree that like paid work, unpaid work itself holds an important social value, defamilization and decommodification need to be understood in a parallel framework rather than from a standpoint of defamilization supplementing decommodification. From the parallel framework, defamilization in this paper can be redefined as the degree to which the society can provide family members with the appropriate degree of care even when in-family care is unavailable. We will attempt to redefine defamilization through Esping-Andersen's (1990) true decommodification. If true decommodification refers to receiving an appropriate level of income at times of no labor market participation due to caretaking, education, or leisure activities, true defamilization may consist of schemes that permit family members to receive an appropriate level of care while parents are pursuing activities other than caretaking, such as working, receiving education, involvement in social activities or leisure3. In addition, just as decommodification includes the possibility of familization of one's labor, a true concept of defamilization implies the possibility of commodification of one's labor. When applied to this paper, defamilization can be understood in line with commodification, and decommodification in line with familization.

Why compare childcare policy between Korea and the conservative welfare states focusing on defamilization and familization? The answer to this question can be found in the process of welfare state restructuring. An impending task of the traditional welfare states was the settlement between capital and labor (Hobson, Lewis, and Siim, 2002). On the other hand, the core task of welfare states under restructuring is the new negotiation between the traditional welfare state based on the male breadwinner and women. In fact, unemployment and pension payments are decreasing, but childcare policy-related expenditures are continuously on the rise (Daly & Lewis, 2000, cited in Hobson, et al., 2002). It was on this ground that Esping-Andersen (1999) pointed to the family as the core of welfare state restructuring.

If female labor market participation is inevitable and people's welfare relies on women's labor market participation, it is only natural that welfare state responsibilities should expand to include defamilization and familization as well as decommodification and commodification. In fact, the process of commodification and decommodification of women employs a conjunction of defamilization and familization, different from that of men who are regarded as exempt from care responsibility.

This is more so because social risks such as child poverty are emerging in association with caregiving (Taylor-Gooby, 2004). LIS data shows that the child poverty related to caregiving is more evident among unskilled female workers in conservative welfare states in which balancing work and family life is hardly feasible (Cantillon, et al., 2001, 447, cited in Taylor-Gooby, 2006). Considering that the tasks related to caregiving comprise one of the major social risks in current welfare states, it would be essential to analyze childcare policies between Korea and the conservative welfare states based on defamilization and familization, both of which are at the core of childcare policy. This analysis would render a discussion of similarities and dissimilarities in childcare policy in these countries.

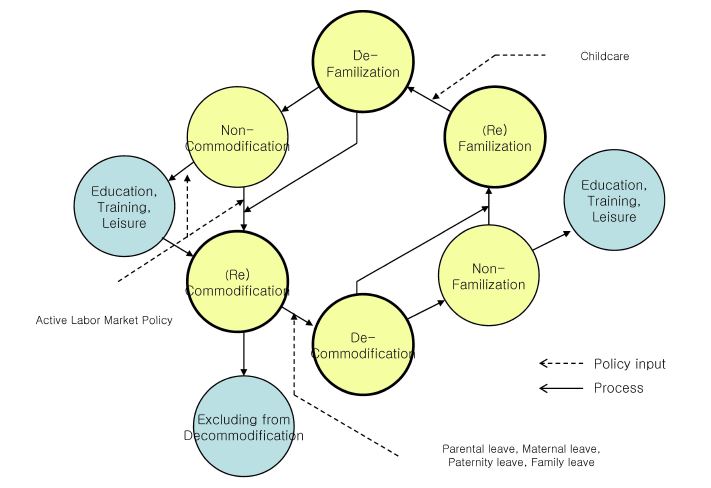

Although familization and defamilization are the main foci of this paper, an integrative discussion of the following concepts is critical: familization, defamilization, commodification, and decommodification. As previously mentioned, familization and defamilization policies have direct and interdependent relationship with those of commodification and decommodification. For example, childcare policy, a form of defamilization policy, serves as a major precondition for female commodification and decommodification (Rauch, 2007), and parental leave, a representative familization policy, assumes decommodification of the commodified parents' labor.

Although limitations exist in schematic diagramming, Figure 1 describes a basic integrated understanding of decommodification, commodification, defamilization, and familization. The starting point is defamilization. Defamilization of care work is rendered through childcare policy. According to Esping-Andersen, defamilization is a precondition for decommodification. Defamilization, however, does not guarantee commodification. Policies based on defamilization are geared toward decreasing the amount of caretaking in the family, but do not necessarily intervene in regard to what care providers will do after defamilization. Defamilization can take caretakers to a noncommodification state by socializing a portion of caretaking responsibilities in the family.

Even if persons become commodified by having the caretaking pressure relieved a through defamilization policy such as childcare, this does not ensure decommodification. Commodified persons can either be decommodified or can be excluded from decommodification. In particular, when we consider the fact that welfare states' response toward social risk in the labor market is institutionalized centering around regular workers, it is quite possible that a person commodified through a flexible labor market would be excluded from decommodification. In fact, 76.7 percent and 76.1 percent of Korean irregular (temporary, part-time, etc.) workers in 20074 were left out of employment insurance and national pension, respectively (Korea Labour and Society, 2007). Furthermore, the rate of irregular workers among women is higher than that of men, therefore, those excluded from decommodification may well mostly be women.

Even if persons are decommodified, this too does not ensure familization. The relationship between decommodification and familization is different according to gender. Parental and maternity leave involve decommodifying labor and familizing it for a certain period of time and these are closely related to the familization of women. In reality, this is not easily applicable to men because in welfare states, most men do not choose decommodification for familization. These gender differences are evident in Belgium. Among those who take the “career break” in Belgium, men utilize the break for education, job training, or early retirement, whereas women use it mainly for child rearing (Devisscher, 2004). In other words, women become familized through decommodification whereas men, even if they become decommodified, are likely to remain non-familized. Even with those men who choose decommodification for familization, it is unclear whether they take the care responsibility within the family. According to an informal source of information, many men in Korea who took parental leave were involved in activities other than childcare.

Finally, workers familized during a certain period of time through the decommodification policy become defamilized through the childcare policy, and are given opportunities to re-enter commodification. Defamilization, commodification, decommodification, and familization are closely interconnected; however, one does not guarantee another. It is based on this notion that we predict the process of familization and defamilization in Korea would be dissimilar to those in conservative welfare states.

France, Belgium, Austria, and Germany are generally categorized as typical conservative welfare states5. Conservative welfare states share attributes such as a social insurance system based on labor market status, horizontal equity, the principle of subsidiarity, and strong familism (Daly, 2001; Morel, 2007). However, there is no single agreed definition of the conservative welfare model. Scruggs and Allen (2006), who reconstructed Esping-Andersen's decommodification index, maintained that the three welfare regimes do not exist. Pointing out the inconsistencies found in seven out of eighteen countries, Daly (2000) also questioned the legitimacy of the welfare regime classification by Esping-Andersen. Particularly in the realm of childcare policy, the focal point of this study, the claim of universal characteristics among conservative welfare states is controversial. Although Esping-Andersen (1990) identified France, Germany, and Austria's conservative welfare systems as the prototype of familism, the argument of similarity among conservative welfare states does not seem so lucid.

Haas (2003) categorized most European countries (with the exception of the Netherlands) as the family-centered care model. Esping-Andersen (1990) identified the low level of social services as a property of family-centered conservative welfare states. These arguments imply that childcare policies in conservative welfare states emphasize within-family care responsibilities. Compared to other European countries, therefore, we may argue that childcare policies in the conservative states are directed at familization rather than defamilization.

This argument, however, is weak to explain the similarity among conservative welfare states, because the rate of childcare in Belgium and France is considerably higher compared to other countries (Morel, 2007). In 2003, the rate of childcare for children between zero and two years of age in Belgium and France was slightly lower than in Sweden and Denmark, but higher than that of Finland and Norway (Blome & Muller, 2007). In addition, Belgium and France have a higher childcare rate for children between three and six compared to four Northern European countries, although the difference is not prominent. In terms of defamilization of childcare, France and Belgium share more similarities with northern European countries than with other conservative welfare states.

The utmost difference in the degree of defamilization in child care lies in the countries' perspective on women and care work. In the Netherlands, childcare responsibility lies solely with mothers and no official state support exists (Anttonen, 2006). In Germany and Austria, most of the responsibility for child rearing is laid on the family (mostly mothers), although the state supports the informal care given by the family. Childcare responsibility in Belgium and France, on the other hand, is imposed on both the state and the family (Morel, 2007; Taylor-Gooby, 2004). The difference gap widens once the social entitlement of women is considered. The social entitlement of women is based on their status as family caregivers in Germany, Austria, and the Netherlands (until recently), whereas in Belgium and France it is based on both family caregivers and workers (Morgan & Zippel, 2003; Sainsbury, 1999; Taylor-Gooby, 2004). The reason for such gap can be traced to unique historical experiences of each country. For instance, a relatively delayed industrial revolution in France leading to the significance of the family farm played a role in sustaining women as workers (Morgan, 2002). Before the Second World War women were considered paid workers in family enterprises and agriculture (Lewis, 1993). Women's status as agricultural workers created a favorable foundation for defamilization policies to expand in France relative to other countries. The concurrent expansion of both defamilization and familization policies in France and Belgium was grounded in the recognition that childcare responsibilities should be shared between the state and family.

Religion is also one of the important factors in explaining the differences as the attributes of family policy are closely interrelated with the degree of religion's political power. States with strong Catholic political power that supports traditional families are more likely to base their women's social entitlement on motherhood. In much of Europe, Christian democratic parties predicated welfare states on the principle of subsidiarity and aimed to preserve the patriarchal family (Morgan, 2002, p. 274). For example, although the religious party in Germany and Austria had contributed to the advancement of social rights, it did not expand to include the social responsibility of child rearing. On the other hand, in France, the secular political power took the leadership after an intense competition between the religious and the secular political power, and the role of religion in welfare expansion was very limited (Morgan, 2002). Welfare expansion in France was relatively untied to the principle of subsidiarity and therefore resulted in a more active role of the state regarding childcare.

In Austria and Germany, where the strong political power of Catholics promoted traditional families, familization policy that supports in-family care became the basic principle of childcare policies. On the other hand, Belgium and France were relatively free from religious influence and therefore development of a defamilization policy that reinforced direct responsibilities of the state was presumably possible. Based on this discussion, we may conclude that family policies in Austria and Germany (specifically, childcare policies) were based on familization whereas France and Belgium aimed at both familization and defamilization. This may explain the deferred commodification and decommodification of women in Austria and Germany. In contrast, France and Belgium maintained a relatively higher level of defamilization policy that increased the possibility of women's commodification and decommodification. It is therefore difficult to conform to Esping-Andersen and others' suggestion that childcare policies in conservative states share similarities based on the family-centered model.

Referring to the above argument, childcare policies in Korea seem to be grounded in familization. Traditional Confucianism that promote gender division of labor still remaining a dominant social ideology, imposing care responsibilities on women, and a low public childcare rate are all signs of familization-based policies. In reality, however, neither familization nor defamilization is receiving adequate amount of support from the state. Similar to the Netherlands before the 1990s, Korea emphasizes family responsibilities for childcare but does not appropriately subsidize either defamilization or familization in regard to childcare.

Methods

Data

A comparative analysis of family policies among different countries is an arduous one (Davaki, 2003; Bruning & Plantenga, 1999). Gauthier (1993, as cited in Davaki, 2003) pointed out four deficiencies in comparability in family policies between states. The first challenge is that no comparable data exist on many cash and in-kind benefits among the countries. Second, the take-up rates of benefits and their coverage are missing; and third, in countries with programs within both central and local government spheres, the data from local governments are unavailable. The last challenge has to do with the fact that benefits from the public sector may not be sufficient when analyzing family welfare, requiring the need to take private sources into account. Furthermore, it is difficult to find reliable data that renders family policy comparability at different time points. These systematic deficiencies pose some limits to the data needed for this analysis. In order to minimize the limitations, the study used the most recent data published by the source country to maximize reliability within given limitations. The data used for the study included OECD Social Expenditure Data (OECD, 2007) and Statistics for Childcare in Korea (Ministry for Health Welfare and Family Affairs [MHWFA], 2008). Secondary data from published articles (Blome & Muller, 2007; Hofcker, 2003) were also employed for analyses.

Variables

Defamilization: Three variables were included as indicators of defamilization. The expenditure on childcare as a percentage of GDP was used to represent a state's actual level of support for defamilization. Two other indicators are childcare rate for children between zero to two and childcare rate for preschoolers aged three and six. Figures from both public childcare and publicly funded childcare were included. The childcare rates that matched the exact years of 1993, 1998, and 2003 for children between three and six years of age were not available; therefore, the average rate that encompassed those years, i. e., the rate between 1990-1993, 1997-2000, and 2001-2004, were used.

Familization: Three variables were used to indicate familization: the maximum duration of parental and maternity leave, expenditure as a percentage of GDP and family allowance, and expenditure as a percentage of GDP alone. The duration of parental and maternity leave were combined to form a single indicator6. For payment level, expenditure on maternity and parental leave as a percentage of GDP was used instead of income replacement rate of maternity and parental leave in order to ensure comparability of coverage and payment. For example, in Sweden, maternity and parental leave cover nearly all parents. In the Netherlands, on the other hand, one has to work 20 hours per week for one year for a single employer in order to qualify for parental leave (OECD, 2006). Therefore, approximately 75 percent of women and 30 percent of men do not meet the requirement. Furthermore, means-tested benefits are difficult to compare with non-means-tested benefits. Due to these complications, expenditure as percentage of GDP of parental and maternity leave was used in place of income replacement rate. Last, family allowance was included as an indicator of familization based on the assumption that cash could create conditions for within-family childcare.

Analysis

In order to compare changes in family policy in conservative welfare states and Korea, cluster analysis and multidimensional scaling were employed using SPSS 17.0. For the cluster analysis, hierarchical clustering technique was utilized and average linkage method between groups was employed for clustering. Cluster analysis was selected based on the expectation that family policy characteristics will differ between countries and between different time periods. For example, even if a country experienced changes over time in family policy, cluster analysis enables us to conclude the changes as statistically meaningful.

Multidimensional scaling (MDS) is generally used for cross-sectional analysis between countries. However, this study intends to examine the change in the direction of family policy among different time periods in a given country. For example, connecting data points in 1993, 1998, and 2003 on a two-dimensional surface will render an analysis of family policy trends in the country of interest. Similarities of cases in cluster analysis and multidimensional scaling were done through Euclidean distance and all values were standardized using z score.

The Euclidean distance between two points xi and yi is expressed as Equation 1, where xi (or yi) is the coordinate of x (or y) in dimension. The test of reliability and validity for MDS was done through Kruskal's stress. Kruskal's stress under 0.1 is excellent and stress over 0.15 is unacceptable (Schiffman, Reynolds & Young, 1981). Stress between 0.1 and 0.15 is considered an acceptable level. Kruskal's stress is calculated according to Equation 2.

Results

Characteristics in Family Policy among Conservative Welfare States and Korea

According to Table 1, France has the highest rate (56.4 percent) of childcare for children between ages of zero and two, followed by Belgium. Germany and Austria have the lowest rate, and the Netherlands and Korea are placed in between. The childcare rate for children between three and six years indicates that most conservative countries utilize the care. Since the differences in childcare rate are minimal for children three and up, the following discussion will center around the younger group.

The childcare rates in France and Belgium, which indicate the level of defamilization, are comparable to the Nordic welfare states. A close examination, however, reveals distinctive features from that of Nordic welfare states. Unlike Nordic welfare states, the social entitlement of women in France and Belgium is based on both their status as a family caregiver and a worker (Morel, 2007). At the same time, they are promoting defamilization through expanding childcare programs. This policy may seem contradictory, but coexistence of disparate principles is not unseen in French history, and family policy is not an exception. In fact, during the formative years of welfare states after the Second World War, France took in both the Bismarckian corporatism and the Beveridge principle of universal rights (Palier & Bonoli, 1995, as cited in Kim, Ahn, Chung, & Hong, 2006, p. 275-276). Such experience is well applied to childcare policies, and is justified on the ground that it gives parents the right to choose what works best for their family regarding childcare (Sabatineli, 2006). After the 1980s, however, the trend in childcare policy shifted to include individual care systems such as direct care by children's own parents rather than reinforcing public childcare facilities. The government expenditure on daycare services between 1994 and 2001 decreased from 16 percent to 8 percent, whereas the assistance to individual forms of care7 increased from 78 to 84 percent (Leprince, 2003, as cited in Morel, 2007). This shift led to classification of childcare preferences among different groups: the low income groups preferred childcare allowance, the middle class daycare programs, and the upper class individual care of their children (Morel, 2007). This trend is also manifested in Belgium, which implies that expansion in childcare facilities and assistance for various childcare systems are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

The low rate of childcare in Germany and Austria shows properties of a typical conservative family-centered family policy (Daly, 2001). The low level of defamilization in Germany, in particular, may be associated with historical strategies of the German women's movement. During the period of welfare state restructuring, German feminists sought for caregiver-parity, and chose childcare allowance and longer maternity leave over defamilization of childcare (Sainsbury, 1999). In fact, from the beginning (1970s) the German women's movement did not consider childcare as a main issue, and as a result the issue faded away in the later movement (Naumann, 2006). Similarly, societal interest in public childcare programs was low in Austria (Morgan & Zippel, 2003), and women were considered as the main caretakers (Stell & Duncan, 2001).

Compared to the four countries discussed above, the changes in the Netherlands are dramatic. In 1993, the childcare rate for the zero to two age bracket was the lowest among conservative welfare states. By 2003, however, the rate had increased by 33.0 percent. This change is unforeseen in a country dominated by the notion that Childcare facilities contradict the meaning of a happy family life and deny the specifically female talents of raising children (Bussemarker & Kerbergen, 1994, p. 23). A unique trait held by the Netherlands amidst this expansion of defamilization is the decreased role of the state and increased responsibility of parents and employers (Knijn & Ostner, 2002).

Korea shares similar properties of conservative welfare states, characterized by underdeveloped social services and women's low labor market participation. What is noticeable, however, is that Korea seems to be undergoing many changes similar to the Netherlands. The childcare budget in Korea has recently increased six times during six years (2002-2008) (MHWFA, 2008). In 2003, the childcare rate for children between zero and two was higher than that of Germany and Austria.

In 2003, France showed the highest rate of expenditure on childcare as a percentage of GDP, followed by the Netherlands and Belgium. Korea had the lowest rate, and Austria and Germany were placed in between. Intriguingly, the expenditure rate of Belgium, a country with a reputation for strong public support of childcare, is lower than that of the Netherlands. The expenditure in Korea amounts to only 20 percent of that in Germany, which showed the lowest rate among conservative states.

According to Table 2, France has the largest number of weeks of maternity and parental leave (172 weeks), followed by Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, and Belgium. Korea marked 59 weeks, which is longer than that in the Netherlands and Belgium. The maternity and parental leave expenditure as a percentage of GDP in Belgium, Germany, France, and Austria is about 0.2 percent to 0.3 percent. The expenditure as GDP percentage was reported as zero for the Netherlands since it has institutionalized the unpaid leave. On the other hand, Korea showed 0.006 percent despite the flat rate payment in the year 2003.

The following is a discussion of characteristics regarding the program in each country. Contrary to other countries, parental leave in the Netherlands was designed to redistribute paid and unpaid work as well as to enable women's return to the labor market (Bruning & Plantenga, 1999). It was designed to share responsibilities of care work between mother and father, and to ensure both familization and commodification. This can be seen through the fact that the use of parental leave was only recently possible in part-time work8. The institutional property of Dutch parental leave confirms that although parents' caretaking is widely supported, the main responsibility lies with the parents. This suggests that familization of parents' labor is of individual choice, and the state is not responsible for their choices. This is contradictory to the state's active support of childcare programs, which leads to defamilization of parents' labor (Knijn & Ostner, 2002). That is, aside from social rhetoric on childcare, parents' labor market participation in the Netherlands is given priority over childcare within the family due to socioeconomic needs.

Paternal leave in France is the very example that shows an ambiguous assumption on the gender issue (Faganai, 1999). The parental leave, CPE, was institutionalized in 1977 as part of an employment policy; it is an unpaid leave and pays a child rearing allowance (APE) until the child reaches 36 months old for those who qualify (not participating in the labor market). However, APE that functioned as reducing the labor force went through reform in 2001 to allow working for the first two months in order to assist women's employment (Palier & Madnid, 2004). In 2006, the program provided a short leave period as well as high payment as an effort to motivate women's rapid return to the labor market (Leitner, 2006). From its introduction in 1985 based on women's familization, APE shifted to implementing means-tested payment and promoting women's return to labor market in the 2000s, which implies similar characteristics of a liberal social security system that reinforces work incentive (Palier & Madnid, 2004).

Belgium shares similar characteristics with France, which developed contradicting policies (Marques-Pereira & Paye, 2003). The parental leave in Belgium, however, is distinct not only from France but the rest of the conservative welfare states. Career break, another form of parental leave, can be used for re-training and leisure in addition to childcare9 (Devisscher, 2004). A formal purpose of the leave policy was job rotation (Marques-Pereira & Paye, 2003). Until 2001, workers substituting for those taking parental leave were limited to the unemployed (Leitner, 2006). The goal of career break is a way of responding to economic crisis rather than to familize childcare (Morel, 2007).

While the major purpose of leave policy in the Netherlands, Belgium, and France is closely related to labor market policy, policies in Germany and Austria emphasize reinforcing women's familization of childcare. However, the two countries have distinctive characteristics. Erziehungsurlaub, the parental leave in Germany, was introduced in 1986 by the conservative Christian Democratic Party and the Liberal Party as a means to stem back childcare program expansions (Scheiwe, 2000). Erziehungsgeld (parental leave benefits) was not designed to sustain the worker's wage but to recognize caretaking within the household (Pettinger, 1999). But through the reform in parental leave, this shifted toward familization based on commodification of parents. In 2000, the right to work part-time during parental leave was institutionalized to assure mother's employment (Leitner, 2006). The reform in 2007 shifted the purpose of benefits from means-tested compensation of care work to income-related benefits designed to sustain one's wage during the leave. With these reforms the properties of parental leave changed from supporting the traditional family role to supporting both familization and decommodification. On the contrary, the parental leave system in Austria reinforces the family care system. The reform in 2002 expanded its eligibility from those with prior employment status to all parents, weakening the association with parents' labor market status (Leitner, 2006).

Parental leave in Korea was institutionalized in 1987 with the enactment of the Equal Gender Treatment Act. However, the real impetus behind the policy was to supplement the decreased labor force of cheap unmarried female workers with married female workers (Kim, 1991). Eligibility for parental leave in Korea is limited to those covered under employment insurance, which does not presuppose withdrawal from the labor market. In addition, it does not share a similar goal with Belgium of job rotation, and does not indicate strong motivation to reinforce familization as shown in Austria. The program itself exhibits a typical form of decommodification and familization based on commodification of parents. However, parental and maternity leave expenditure as percentage of GDP in Korea is 0.006 percent; it covers a very limited group of people and the level of payment is also very low (18 percent of average wage). Among those who gave birth in 2003 (based on number of births) only 6.5 percent and 1.4 percent used maternity leave and parental leave, respectively.

Family allowance as cash benefits could increase familization of parents' labor. Austria's family allowance expenditure as percentage of GDP is the highest (2.2 percent) among countries included in the analysis. Korea currently has no institutionalized family allowance. It is noticeable that the expenditure levels have decreased in all comparing countries except for Austria. In the cases of the Netherlands and Belgium, the expenditure decreased by 36.4 percent and 25.0 percent, respectively, in the past ten years. These figures reflect that policies in conservative welfare countries are shifting toward supporting defamilization. On the contrary, Austria exhibits reinforced traditional family roles even after 2000 (Leitner, 2006) which may be related to an increase in family allowance.

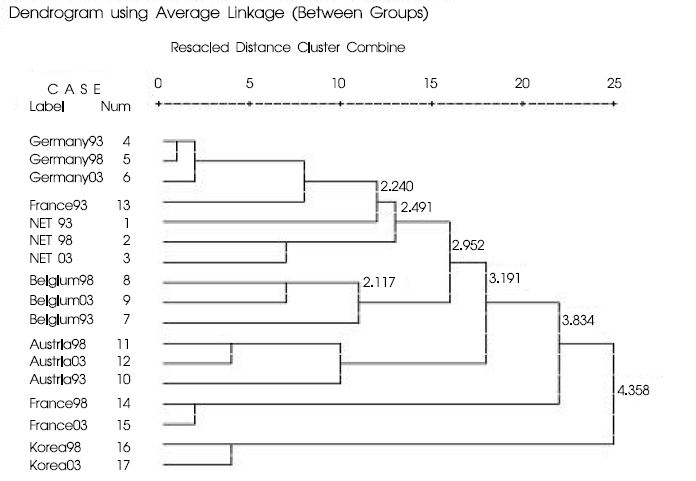

The cluster coefficient of 3.0 was utilized for the cluster analysis. According to Figure 2, ten cases from France in 1993, Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands create one cluster (cluster coefficient=2.952). Three cases from Austria (cluster coefficient=2.068), two cases from France (1998, 2003, cluster coefficient=0.771) and Korea (cluster coefficient=1.062) formed other separate clusters.

Detailed examination of the result indicates that France became an independent cluster after 1998, whereas Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, and France still comprised a cluster in 1993. The main reason for France's location in a separate cluster from Belgium in 1998 and 2003 may be traced to the rapid increase in childcare rate (zero to two age bracket) and childcare expenditure after 1998. During the analysis period, Austria formed a cluster of its own different from other conservative states. Of note is that Germany and Austria, which are said to share common characteristics in general, fell in different clusters. This distinction may result from the Austrian government's stronger support of familization policy.

In the past decade, the Netherlands showed a marked improvement in the defamilization index, taking the lead from Germany and Austria in all three defamilization indices in the early 2000s. In 2003, it led all conservative countries, with the exception of France, in childcare expenditure. These changes, however, are not enough to place the country's childcare policy in a cluster independent from neighboring conservative welfare states. Korea shares similar characteristics with conservative welfare states in its socioeconomic condition and values; however, with the low level of policy index in familization and defamilization, it was placed in a different cluster. This shows that shared social values and circumstances do not necessarily result in shared characteristics in policy.

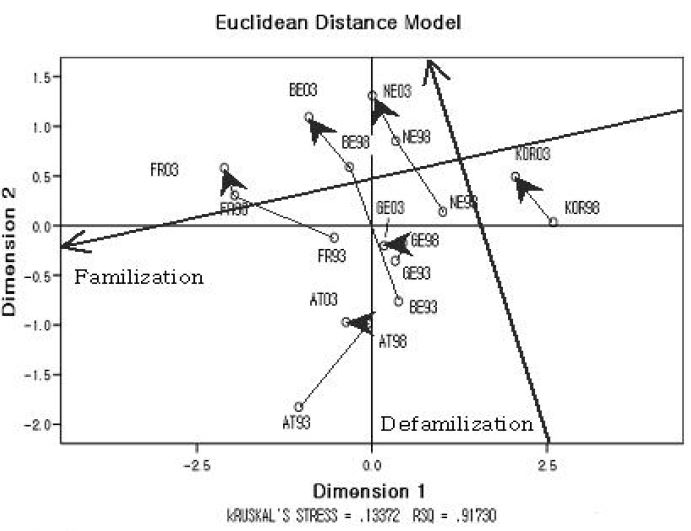

Figure 3 shows results from multidimensional scaling and cluster analysis. The Kruskal's stress from multidimensional scaling was 0.13372, indicating an acceptable level of fit, and it explained 91.37 percent of the variance (R2=91.370). The axes in multidimensional scaling can be set variably, and this study set two axes: defamilization and familization. The top left axis refers to the support level for defamilization policy, and the lower left axis indicates the familization policy. Moving toward the top left indicates a higher support for defamilization, and to the bottom left direction indicates support for familization.

An examination of family policy changes based on multidimensional scaling and cluster analysis results suggests that all countries slightly shifted toward defamilization after the year 1998. Support for most familization programs is stagnating or decreasing while there is an increase in childcare rate and the expenditure on childcare, both of which are defamilization indicators. In Austria, familization support decreased between 1993 and 1998, but began to increase between 1998 and 2003.

In the larger picture, except for France, there are no evident qualitative changes in family policy in conservative states nor in Korea. This is supported by the fact that most countries included in the study stayed in the corresponding cluster in the past ten years. In the comparative analysis between conservative welfare states, Leitner (2006) maintained that prior similarities between Germany and Austria, and France and Belgium are shifting toward common traits shared between Austria and Belgium, and Germany and France. An analysis of family policy based on defamilization and familization, however, yields no such trend during the period up to 2003.

Conclusion

Through a comparative analysis in family policies between conservative welfare states and Korea, several noticeable results were found. First, contrary to general expectation, there were no common similarities among conservative welfare states in the realm of family policies. It is notable that France and Belgium separated into different clusters, as well as did Austria and Germany, who have been considered to share similar characteristics. These findings explicate that conservatism may not be a pertinent concept to categorize conservative states, at least not in the realm of childcare policy.

Second, although childcare policies in conservative welfare states have been changing continuously in the last ten years, qualitative changes were not found except for France. However, findings hinted at the countries' efforts to reinforce defamilization after the 1990s. In fact, even Germany, which emphasizes family responsibilities in regard to childcare, proclaimed a universal childcare for those between three and six (Morel, 2007). These changes may be directly related to the advent of commodification of women and human capital development as a necessary condition for strengthening states' competitiveness. For example, the Netherlands expanded its attention and support for childcare after recognizing that the neglect of female human capital led to welfare state crisis (Morel, 2007).

Third, Korean childcare policy may seem to share major characteristics with conservative welfare states in rhetoric, but the actual policy differs substantially from those in the conservative states. Korean experience presented that shared social values and circumstances do not necessarily result in similar policies. Social conditions in Korea and its values are similar to those in the conservative countries but its policies are similar to liberal welfare states, characterized by the absence of an active state role. In other words, with the discrepancies between social rhetoric and policy, it would be difficult to characterize Korean childcare policies as sharing traits of the conservative states.

Results from the current study have two implications in Korean family policy development. First, even the Netherlands, with relative stronger familism, is moving toward expanding defamilization policies. This becomes more evident in the late 1990s. The Netherlands' experience of expanding social responsibilities of childcare to render continuous development of the welfare state could be applied to the current Korean society. With current circumstances that require dual earners for families with children to stay out of poverty, women's employment is mandatory for individual households as well as for Korean society in general. This may lead to public agreement toward defamilization in regard to childcare.

Second, France maintained higher levels in both familization and defamilization indices than other conservative states, which indicates that support for familization and defamilization can be complementary. This implies that familization policy expansion based on familism may be achieved in line with an expansion in defamilization policy. Learning from the experiences of France and Belgium, however, the expanding familization policy must meet the following criteria: 1) Familization duration should not be long enough to lessen parents' (mainly mothers') work incentive; 2) The level of payment during the familization period should be enough for the family to maintain an independent living without depending on the male breadwinner, which would reproduce a traditional gender division of labor; and 3) Family policy should be in close touch with commodification strategies. As in France and Belgium, sending women back to their families as a means to relieve labor market predicaments like unemployment would be untimely.

Notes

2 Similar concerns are manifested among feminist scholars. Like Esping-Andersen (1999), Lister (2003) also defined defamilization as the degree to which individual adults can uphold a socially acceptable standard of living, independently of family relations, either through paid work or through social security provisions.

3 Based on this notion of decommodification and defamilization, commodification and familization in this paper can be defined as the following: Commodification refers to parents' selling their labor in the market, and familization denotes parents taking care of their children.

4 2007 figures are based on March data.

5 Haas (2003) categorized the Netherlands as a market-oriented care model along with England and Ireland. However, the Netherlands shares common ground with family policies in other conservative welfare states in that it considers women as the main childcare provider.

6 Of the six countries, Korea has a 45 days overlap between maternity and parental leave. In such case, the overlapping days were subtracted from the total days of leave. Until 2008, the length of parental leave in Korea was up to one year after childbirth, which leads to about 45 days of overlap.

7 Various kinds of child cash benefit programs merged to PAJE (Prestation d'Accueil du Jeune Enfant) in 2004 (Morel, 2007).

8 Currently, a full 13 weeks can be used as a parental leave and in 2000, all workers were given the right to the leave (Knijn and Ostner, 2002).

9 There was a reform in 2002 that replaced the existing system with thetime credit scheme (Devisscher, 2004).

References

- Anttonen, A., (2006), Toward a European childcare regime?, Paper presented at the 4th Annual ESPAnet Conference. Bremen. Retrieved September 11, 2006, from http://www.espanet2006.de/.

- Blome, A., & Mller, K., (2007), Attitudes towards mothers' employment and family policies in 11 European welfare states, Paper presented at the 5th Annual ESPAnet Conference. Retrieved January 1, 2008 from http://www2.wuwien.ac.at/espanet2007/06_Blome_Agnes.pdf.

-

Bruning, G., & Plantenga, J., (1999), Parental leave and equal opportunities:

Experiences in eight European countries, Journal of European Social Policy, 9(3), p195-209.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/095892879900900301]

-

Bussemaker, J., & Kersbergen, K., (1994), Gender and Welfare States: Some

Theoretical Reflections. In D. Sainsbury (Ed.), Gendering Welfare States, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, p8-25.

[https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446250518.n2]

- Daly, M., (2000), The Gender Division of Welfare, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Daly, M., (2001), Globalization and the Bismarckian Welfare States. In R. Sykes, B. Palier, & P. Prior (Eds.), Globalization and European welfare states, Palgrave, New York, p79-102.

- Davaki, K., (2003), Women-friendliness of labour market and family policies in Germany and Greece, Paper presented at the 1st Annual ESPAnet Conference. Retrieved October 11, 2004 from http://www.espanet.org/.

- Devisscher, S., The Career Break (Time Credit) Scheme in Belgium and the Incentive Premiums by the Flemish Government, Discussion Paper, Peer Review Program of the European Employment Strategy. Retrieved October 11, 2004, from http://www2.vlaanderen.be/werk/documenten/euro_Discussionpaper.pdf.

- Esping-Andersen, G., (2004), The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, (1990).

-

Esping-Andersen, G., (1999), Social Foundations of Postindustrial Economics, Oxford University Press, New York,

NY.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/0198742002.001.0001]

- Fagnani, J., (1999), Parental Leave in France. In P. Moss & F. Deven (Eds.), Parental Leave: Progress or Pitfall? Research and Policy Issues in Europe, CBGS Publications, Hague, Brussels, 35, p69-83.

-

Haas, L., (2003), Parental leave and gender equality: Lessons from the European Union, Review of Policy Research, 20(1), p89-114.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-1338.d01-6]

- Hobson, B., Lewis, J., Siim, B., (2002), Introduction: contested concepts in gender and social politics. In B. Hobson, J. Lewis, & B. Siim (Eds.), Contested concepts in gender and social politics, Edward Elgar, MA, p1-22.

- Hofcker, D., (2003), Towards a dual earner model? European Family Policies in Comparison, Globalife Working Pape, (49).

- Kim, S., Ahn, S., Chung, B., & Hong, T., (2006), Je 3 Ui Gil Gwa Sinjayujuui [The Third Way and Neo-liberalism in United Kingdom, Germany, and France], Seoul National University Press.

- Kim, Y. O., (1991), Je 6 Gonghwagug Ui Yeoseong Nodong Sijang Jeongchaek [Women's labor market policy in the 6th Republic of Korea], Samujigyeoseong [Women in Clerical Work], 4(1), Korean Womenlink.

- Knijn, T., & Ostner, I., (2002), Commodification and de-commodification. In B. Gobson, J. Lewis, & B. Siim (Eds.), Contested concepts in gender and social politics, Edward Elgar, MA, p141-169.

- Korea Labour and Society, (2007), The scope and realities of nonregular workers. Retrieved December 9, 2007 from http://klsi.org/.

-

Leitner, S., (2006), Varieties of familialism: The Caring Function of the Family in

Comparative Perspective. European Societies, 5(4), p353-375.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/1461669032000127642]

- Lewis, J., (1993), Introduction: Women, work, family and social policies in Europe. In J. Lewis (ed.), Women and social policies in Europe, Edward Elgar, Vermont, p1-24.

-

Lister, R., (2003), “Investing in the Citizen-workers of the Future: Transformations

n Citisenship and the State under New Labour.”, Social Policy and Administration, 37(5), p427-443.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9515.00350]

- Marques-Pereira, B., & Paye, O., (2003), Belgium: The vices and virtues of pragmatism. In J. Jenson & M. Sineau (Eds.), Who cares? Women's work, childcare, and welfare state redesign, University of Toronto, Toronto, p56-87.

- Ministry for Health Welfare and Family Affairs, (2008), Statistics of Childcare. MHWFA.

-

Morel, N., (2007), From subsidiarity to 'free choice'; Child-and elder-care policy

reforms in France, Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands, Social Policy and

Administration, 41(6), p618-637.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9515.2007.00575.x]

-

Morgan, K., (2002), The politics of mothers' employment France in comparative

perspective, World Politics, 55, p259-289.

[https://doi.org/10.1353/wp.2003.0013]

-

Morgan, K., & Zippel, K., (2003), Paid to care: the Origins and effects of care

leave policies in Western Europe, Social Politics, 10, p49-85.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxg004]

- Naumann, I., (2006), Childcare politics in West Germany and Sweden since World War II: Historical cleavages, social compromises, and policy outcomes, Paper presented at the 4th Annual ESPAnet Conference. Retrieved September 11, 2006, from http://www.espanet2006.de/.

- OECD, (2006), Starting Strong II: Early Childhood Education and Care, OECD Publication, France.

- OECD, Social Expenditure Database, OECD Publication, France, (2007).

-

Palier, B., & Mandin, C., (2007), France: A New world of welfare for new social

risks? In P. Taylor-Gooby (Ed.), New risks, new welfare, Oxford University Press, New

York, p111-131.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/019926726X.003.0005]

- Pettinger, R., (1999), Parental Leave in Germany. In P. Moss & F. Deven (Eds.), Parental Leave: Progress or Pitfall? Research and Policy Issues in Europe, CBGS Publications, Hague, Brussels, 35, p123-140.

-

Rauch, D., (2007), Is there really a Scandinavian social service model? A comparison

of childcare and elderlycare in six European countries, Acta Sociologica, 50(3), p249-269.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699307080931]

- Sabatinelli, S., (2006), Developments in childcare between public and private investment: A comparison between Italy and France, Paper presented at the 4th Annual ESPAnet Conference. Retrieved September 11, 2006, from http://www.espanet2006.de/.

-

Sainsbury, D., (1999), Gender, Policy Regimes, and Politics. In D. Sainsbury (Ed.), Gender and welfare state regimes, Oxford University

Press, New York, p245-275.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/0198294166.003.0009]

- Scheiwe, K., (2000), Equal opportunities policies and the management of care in Germany. In L. Hantrais (Ed.), Gendered policies in Europe: Reconciling employment and family life, Martin's Press, INC.St. Martin's Press, INC, New York, p89-107.

- Schiffman, S., Reynolds, M., & Young, F., (1981), Introduction to Multidimensional Scaling: Theory, Methods, and Applications, Academic Press, New York.

-

Scruggs, L., & Allan, J., (2006), Welfare-state decommodification in 18 OECD

countries: a replication and revision, Journal of European Social Policy, 16(1), p55-72.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928706059833]

-

Strell, M., & S. Duncan, S., (2001), “Lone motherhood, ideal type care regimes and

the case of Austria”, Journal of European Social Policy, 11(2), p149-164.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/095892870101100204]

-

Taylor-Gooby, P., (2004), New risks and social change. In P. Taylor-Gooby (Ed.), New risks, new welfare, Oxford University Press, New York, p1-28.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/019926726X.003.0001]

- Taylor-Gooby, P., (2006), European Welfare Reforms: the Social Investment Welfare State, Paper presented at 2006 EWC/KDI Conference, social policy at a crossroad: Trends in Advanced Countries and Implications for Korea. Honolulu on July 20-21, 2006.

-

Timonen, V., (2004), New risks-Are they still new for the Nordic Welfare States? In P. Taylor-Gooby (Ed.), New risks, new welfare, Oxford University Press, New York, p83-110.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/019926726X.003.0004]