Female Dancers’ Organizational Commitment

This study examined the relationships among three variables of female dancers’ organizational identification, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment. Although considerable numbers of previous studies have investigated the relationship among the variables, female members’ organizational attitude and behaviors need more attention from practitioners and theorist as well. This study developed three competing models based on theoretical background. The data were collected from six different dance teams in the Republic of Korea. A total of 156 female professional dancers participated in the study. The three competing models were tested using the structural equation modeling (SEM). The results indicated that organizational identification influenced job satisfaction and organizational commitment and job satisfaction influenced organizational commitment.

Keywords:

female dancers, organizational commitment, organizational identification, job satisfactionIntroduction

Organizational studies have examined the behaviors of members in order to increase the effectiveness and efficiency of their organizations. Among those, many studies have investigated psychological constructs related to organizational members such as commitment, identification, satisfaction, etc (Cole & Bruch, 2006). Particularly, many previous studies were interested in the relationships among those variables since they were known to influence members’ turnover intention and job performance (Cole & Bruch, 2006; Herrbach, 2006; Tuzun, 2009). However, as previous studies indicated (e.g., Elizur & Koslowsky, 2001; Scandura & Lankau, 1997), more research needs to be done with female members of organizations. Particularly, the relationships between organizational identification, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment among female members of dance organizations have never been examined. Considering the unique characteristics of a dance team (e.g., relatively smaller size, gender dominance by female, lower wage, less fringe benefits and early retirement in comparison to employees in other sectors), it is imperative to figure out proximal cause and effects of job satisfaction among female members of dance teams. In addition to the environmental differences of dance teams, they are very unique in that each member’s contribution to the team’s performance on a stage is direct and clear for each performance. The members of the organization personally and directly participate in producing the outcomes (i.e., dance performance) all together under the leadership of the captain. Due to the aforementioned uniqueness of dance organizations, the relationship among organizational identification, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment needs to be reexamined using dominant members of a dance team: female professional dancers.

The objective of the study is two-fold. First, the study attempted to develop a conceptual model between organizational identification, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment based on literature review. The literature review included very extensive studies of each variable so that we could establish a sound theoretical support for each model. Second, the study attempted to select the best fitting model using a data set from dance teams located in Seoul and its vicinity in South Korea.

The results of this study can provide valuable insights into whether previous findings are applicable to unique aspects of dance teams. In addition, this study can contribute to the body of organizational literature by discovering the effects of organization related constructs among female professional dancers. The following section provides extensive literature review on three variables of organizational identification, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment in the context of general organizations and dance organizations as well.

Theoretical Framework

Organizational Identification

Organizational identification originated from the social identity theory of Tajfel and Turner (1985). It is a social process in which a person defines himself or herself. It is about who I am and what others think about the self (Tajfel & Turner, 1985). The group identification has been studied heavily in organizational studies because group identification is related to a number of desirable group outcomes (Albert, Ashforth, & Dutton, 2000; Riordan & Weatherly, 1999). Although many studies have tried to investigate the underlying constructs of identification, recent empirical works tend to conceptualize organizational identification as a unidimensional construct and this has been accepted as a reasonable and useful methodology for evaluative purposes (Rotondi, 1975).

The recent conceptualization of identification is characterized with its parsimoniousness. Mael and Ashforth (1992, p. 109) defined organizational identification as “a perceived oneness with an organization and the experience of the organization’s successes and failures as one’s own”. And Dutton, Dukerich, and Harquail (1994, p. 239) defined it as “the degree to which a member defines him or herself by the same attributes that he or she believes define the organization”. The two definitions of organizational identification represent one line of organizational identification study. Another line of organizational identification study is emphasizing the congruency between member’s value and that of organization (Hall, Schneider, & Nygren, 1970; Lee, 1971).

Dutton et al. (1994) also noted the consequences of organizational identification. They pointed out that members with strong organizational identification (a) evaluate the image of the organization as more attractive, (b) will seek more contact with the organization, (c) will cooperate better with other members of the organization, (d) will show more competitive behavior directed toward out-group members, and (e) will exhibit organizational citizenship behavior more often than the members with weak organizational identification. In a more recent study, organizational identification was found to have positive correlations with organizational commitment and job satisfaction (Tuzun, 2009). Based on the literature, female members of dance teams are expected to develop organizational identification much easier than in other types of male dominant organizations due to the nature of dance. Particularly, in a Confucian culture like Korea, gender specific role has been strongly and strictly applied among its members. Thus, the fit between the image of dance and the female’s traditional image would enhance the congruence between the members and the organization (i.e., dance teams). The fit between organizational members and organizational culture was found to positively influence organizational performance such as organizational commitment and job satisfaction (Behery & Paton, 2008).

In conclusion, previous literature on organizational identification indicates that it is a cognitive process of categorizing oneself and identification strengthens when members categorize themselves into their organization (Dutton et al., 1994). The organizational identification of dancers toward their respective dance team would do the same thing as suggested in previous literature. The dancers who are identified highly with their dance team would show a higher organizational commitment and job satisfaction.

Organizational Commitment

Commitment is a psychological state that has been used to explain diverse behaviors of organizational members. Commitment is the attitude an individual has toward a specific target, which is the dance team that the members are working for. Commitment is a term that has been frequently used in academic disciplines as well as in daily life. Kiesler and Sakumura (1966, p. 349) define it as “the pledging or binding of the individual to behavioral acts.” Becker (1960) describes commitment as a process by which an individual stakes something of value to him, something originally unrelated to his present line of action. In summary, there are two notions emphasized through the definitions provided. First, it is an attitudinal term that influences one’s behavior. Second, it is a force that makes individual behavior consistent. So it can be inferred that the effect of commitment is “to make an act less changeable” (Kiesler & Sakumura, 1966, p. 349).

Personal commitment refers to a strong personal dedication to a decision or to carrying out a line of action whereas behavioral commitment refers to prior actions by the individual that force him or her to continue a line of action, whether or not one is personally committed to it. Behavioral commitment is the case in which an individual acts differently from his or her belief. These concepts may be illustrated in a scenario between an organization and its members. If one is personally committed to the organization, he/she is less likely to leave the organization even though he/she receives better offers from other organizations. In this case, the target of the employee’s commitment is the organization itself. The employee stays because he/she wants to stay and work for the organization. This concept is termed as affective commitment in a recent organizational study. Meyer and Allen (1991, 1997, p. 235) define it as “identification with, involvement in, and emotional attachment to the organization.” Based on Johnson’s (1973) dichotomization, the affective commitment is similar to the personal commitment that refers to a strong personal dedication to a decision or to carrying out a line of action. The organizational commitment of Porter, Steer, Mowday, and Boulian (1974) represents the affective component of Meyer and Allen’s organizational commitment (Allen & Meyer, 1990).

The second dimension of Meyer and Allen’s (1984) conceptualization is continuance commitment and it refers to “awareness of the costs associated with leaving the organization” (Meyer & Allen, 1991, p. 67). The concept of continuance commitment is similar to Johnson’s (1973) behavioral commitment, which is described as prior actions by the individual that force him or her to continue a line of action, whether or not one is personally committed to it. The continuance commitment forces a member to remain in the present organization because he or she needs to do so and this is the offshoot of Becker’s (1960) Side-Bet Theory of organizational commitment (Meyer & Allen, 1984). The continuance commitment is also similar to the compliance dimension of O’Reilly and Chatman’s (1986) organizational commitment in that it is the external force that influences the behavior of a human being. Later, the continuance commitment was divided into two highly related subscales: lack of alternatives and personal sacrifice (Meyer, Allen, & Gellatly, 1990).

However, different from other general organizations, the application of continuance commitment to Korean professional dancers has not been supported conceptually and empirically as well. Choi and Choi (2007) indicated that the dancers are personally committed to “dance” although their pension plan and salary is very limited. This suggested that continuance commitment should not be a type of commitment that the dancer would experience. In addition, previous literature also found a significant gap between the prediction and empirical findings when it pertains to continuance commitment (Dunham, Grube, & Castaneda, 1994; cited from Choi, 2004). Based on the aforementioned reasons, the continuance commitment was not included in the current study.

The third, normative commitment was added to the previous two dimensions of organizational commitment and is defined as a feeling of obligation to continue the membership in the present organization. Originally, the idea of obligation-based commitment was first shown in Wiener (1982, p. 471) and was defined as “the totality of internalized normative pressures to act in a way which meets organizational goals and interests”. Employees with a high level of normative commitment feel that “they ought to remain with the organization” (Meyer & Allen, 1991, p.67).

Although conceptually supported by Meyer and Allen (1991), the normative commitment has been found to lack discriminant validity in several previous studies (e.g., Ko, Price, & Mueller, 1997; Meyer, Allen, & Smith, 1993). Among the two studies, Ko et al.’s (1997) study was about Korean population. Thus, it has good applicability to the current study. Based on the aforementioned reasons, normative commitment was also excluded from the measure of organizational commitment among Korean female professional dancers.

Based on the literature review of organizational identification and organizational commitment, it can be conjectured that the two constructs are correlated. This was also empirically supported by many previous studies (Herrbach, 2006; Meyer & Allen, 1991, 1997). However, in determining a possible causal relationship between the two constructs, theoretical support is necessary. According to Meyer and Allen (1997), the construct of affective commitment includes identification, involvement, and emotional attachment, which are stronger attachments to a target than that of identification. Organizational identification is known to be very cognitive (Foote, 1951; Kagan, 1958) and not necessarily related to a certain behavior. This traditional view was again asserted by Dutton et al. (1994) in that it is a cognitive image held by a member of an organization. Thus, it can be concluded that organizational identification is an antecedent of organizational commitment.

Job Satisfaction and Relationships with Organizational Identification and Commitment

Job satisfaction is personal perception on the job that one holds. Spector (1997) defined it as how people feel about their jobs and the different aspects of their jobs. Several empirical studies are available regarding female members’ job satisfaction. Cohen and Liani (2007) examined the job satisfaction of female health care administrators in Asian context in relations to their work-family conflict. This study found that the level of work-family conflict is negatively correlated to their level of job satisfaction. The implication of the study is quite relevant to the current study in that the results were from female members in a non-Western culture. The findings from Western culture regarding female members’ job satisfaction have been quite inconsistent. Some studies found that male members were more satisfied with their jobs whereas other studies found the opposite (e.g., Forgionne & Peters, 1982; Hickson & Oshagbemi, 1999; Mottaz, 1986; Ward & Sloane, 1998).

Job satisfaction has been studied mostly as a dependent variable in organizational studies. One of the most frequently employed independent variables was organizational identification. Previous studies indicated that the members with high organizational identification would stay in the organization longer due to decreased alienation (Dutton et al., 1994), engage in more supportive behaviors (Shamir, 1990), and choose to carry out activities beneficial to his/her organization (Lee, 2004). In addition, Pratt (1998) and Van Dick, Wagner, Stellmacher, and Christ (2004) also found that organizational identification decreased negative organizational behaviors such as turnover and conflicts with an organization. Recent work of Brunetto and Farr-Wharton (2002) and Tuzun (2009) also indicated a causal relationship between organizational identification and job satisfaction. Thus, the causal relationship between organizational identification and job satisfaction has been quite apparent conceptually and empirically as well.

The link between organizational commitment and job satisfaction is unfortunately not as clear as the relationship between organizational identification and job satisfaction. The relationship has been studied using various hypotheses between the two variables. The most frequently suggested hypotheses are two: job satisfaction causes organizational commitment and organizational commitment causes job satisfaction. In addition to the two most frequently suggested hypotheses, several studies argued that the correlation between the two variables should be spurious due to similar antecedents of the two variables (Curry, Wakefield, Price, & Muller, 1986; Dougherty, Bluedorn, & Keon, 1985). Currivan (2000, p. 499), although noted that this approach had “some appeal,” criticized it based on lack of empirical evidences.

Mowday, Porter and Steers (1982) indicated that job satisfaction should be an antecedent of organizational commitment based on two reasons. First is that commitment takes longer to form than does job satisfaction. Second, a member can only be committed to an organization after he/she is satisfied with the job. In addition to Mowday et al. (1982), many studies such as Steer (1977), Porter et al. (1974) also empirically supported that job satisfaction influenced commitment. On the contrary, Bateman and Strasse’s (1984) study and Vandenberg and Lance (1992) argued that organizational commitment is an antecedent of job satisfaction using longitudinal data from nursing department employees. Bateman and Strasse (1984) indicated that the unclear causal relationship between the two variables in the previous studies was attributed to the structure of research which mainly utilized zero-order correlations and regression analyses with concurrent nature. Bateman and Strasse (1984) and Vandenberg and Lance (1992) indicated that, with a general social psychological perspective, employees should adjust their level of satisfaction based on their current level of commitment. In summary, two causal relationships are still possible and equally appealing. Mowday et al. (1982) have a valid point with good conceptual understanding. At the same time, however, the study of Bateman and Strasse (1984) supported their view using a more robust research design.

Model Development

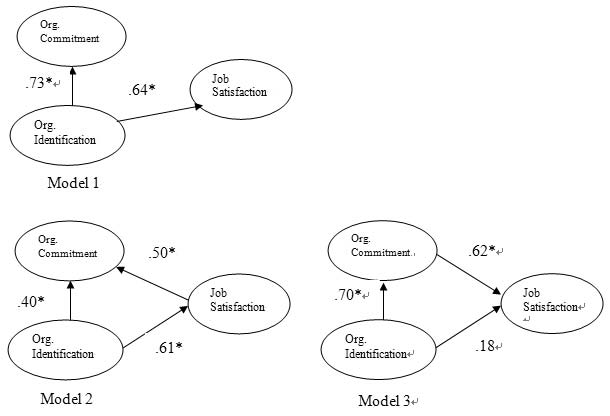

Based on previous studies three models were developed. Model 1 was developed based on the notion that organizational commitment and job satisfaction are not related. Thus, Model 1 included a causal relationship from organizational identification to job satisfaction and a causal relationship from organizational identification to organizational commitment. The two constructs of organizational commitment and job satisfaction are not correlated. Model 2 was constructed based on the notion that job satisfaction was an antecedent of organizational commitment. In this model three specifications were included as show in Figure 1. Model 3 was developed based on Bateman and Strasse (1984) that organizational commitment is an antecedent of job satisfaction.

Method

Participants

The data were collected from six different dance teams in the Republic of Korea. A total of 204 dancers participated in this study. Among the 204, male dancers’ data were removed from the further analyses. A total of 156 responses were included in data analyses. Six dancers from Seoul Performing Arts Company, 30 dancers from Gyeonggi Provincial Dance Company, 28 dancers from The National Center for Korean Traditional Performing Arts, 24 dancers from Uijeongbu Arts Center, 30 dancers from Incheon Metropolitan City Dance Theatre, and 38 dancers from The National Dance Company of Korea. The mean age of the respondents was 29.21 with standard deviation of 5.11. Thus, the members were quite a wide-spread in terms of age. Among 156 women dancers, 106 dancers were single and 49 were married. Most of the dancers were college graduates (99.4%). The average experience in the current dance team was 71.76 months. Most of the dancers (96.8%) were paid by their respective dance team.

Instrument Development

A questionnaire was developed for this study. The questionnaire included four scales in addition to demographic items. First, organizational identification was measured with Mael and Ashforth’s (1992) six items of organizational identification. The wording of items was modified to fit the current study. The organization’s name was substituted with “The dance team that I am currently working for”. Organizational commitment was measured with affective commitment scale of Meyer and Allen (1991). The job satisfaction was measured with three items from Brayfield and Rothe (1976). All the scales were anchored with the five point Likert scale (‘1’ strongly disagree and ‘5’ strongly agree). In addition to three scales, demographic questions are included to measure their gender, age, marital status, educational background and position in her dance team. Also, a question was included to find out whether the respondents were paid by their dance team.

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed in three steps. First, descriptive statistics were calculated. In this phase, missing values and outlier were examined. Also, normality of the data was examined using skewness and kurtosis. Second, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to examine the factor structure of the three variables of organizational identification, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction. Using the information from CFA, convergent validity and discriminant validity were examined. Third, the three competing models were compared using structural equation modeling (SEM).

Results

First, descriptive statistics were calculated with SPSS 16.0. Table 1 included means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis of the three constructs. The means of the organizational identification and commitment constructs were greater than the median value of three, which indicated that the Korean dancers are identified with and committed to their dance team. The mean of job satisfaction was also greater than three indicating that they were relatively satisfied with their dance group. The skewness and kurtosis values of the three constructs were normal enough to utilize maximum likelihood estimation for CFA and SEM. The internal consistency of the three constructs was measured with Cronbach’s alpha. The Cronbach’s alpha values were .90, .90, and .89 respectively for organizational identification, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction. All three subscales were found reliable based on Nunnally and Bernstein’s criteria (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994).

Second, a CFA for the three constructs was performed using AMOS. The model fit indices indicated that the data fit the CFA model fairly well: Chi-square/df = 185.9/87 = 2.136, RMR = .049, TLI, 930, CFI = .942, RMSEA = .086. The average variance extracted values are presented in Table 2. The AVE values were all greater than .5 as recommended by Hair, Anderson, Tatham, and Black (1998). All the standardized factor loadings except one organizational commitment item (Commit 1 = .68) were greater than .707, which indicated good convergent validity of the scales. The discriminant validity was measured by calculating the correlations among the three variables. The correlation between organizational identification and organizational commitment was .70. It was .61 between organizational identification and job satisfaction and .74 between organizational commitment and job satisfaction. No correlation was bigger than .85 (c. f., Kline, 1998). This indicated that the three constructs were differentiated enough to establish a sound discriminant validity.

After confirming the structure of three latent constructs of organizational identification, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction of female professional dancers in Korea, three SEM models were constructed based on previous literature. The models were depicted in Figure 1. The three SEM models were also tested using AMOS and the results were presented in Table 3. Model 1 showed the worst model fit indices. Since Model 1 is nested in Model 2, the two models were compared using chi-square statistics difference test. The difference was 201.83 with df of 2, which is statistically significant at α = .05 level. Thus, Model 1 was concluded to be inferior to Model 2. The next comparison was made between Model 2 and Model 3. The two models were not nested to each other. As presented in the Table3, the fit indices of the two models were perfectly identical. Thus, the two models equally fit to the data. However, the path between organizational identification and job satisfaction in Model 3 was not significant (p = .06). Thus, Model 2 gained more theoretical support using the data set.

Relationships among organizational identification, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment: A comparison of the three competing models Note. * Significant at alpha level = 0.5

To compare Model 2 and Model 3 in detail, squared multiple correlations (SMC) were calculated. In Model 3, the SMC of job satisfaction was .38 whereas it is.57 for organizational commitment in Model 2. Thus, the two variables of organizational identification and job satisfaction had more explaining power on organizational commitment than organizational identification and organizational commitment on job satisfaction. Thus, using the SMC, Model 2 was, again, found to be a better model.

Discussion

This study was interested in women professional dancers’ organizational identification, commitment, and job satisfaction. The relationships among the three variables using previous literature were extensively examined. Consequently, three different models were constructed. The results of the three SEMs indicated that Model 1 had the worst fit whereas Model 2 and Model 3 equally fit the data from women professional dancers. Model 1 was developed based on several studies (e.g., Curry, Wakefield, Price, & Mueller, 1986; Dougherty et al., 1985) that argued that the relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment was spurious because they both share common antecedents. Although their argument was valid in that many psychological constructs found in organizational settings have been found to be antecedents of both variables, empirical support is still lacking. The results of the current study also indicated that Model 1 showed the worst fit due to the high correlation between job satisfaction and organizational commitment (r = .74). Accordant with previous literature, this study also failed to provide empirical support for Model 1.

The rationale behind Model 2 and Model 3 are equally robust. Model 2 has been supported based on the nature of the two variables of job satisfaction and organizational commitment. As Mowday et al. (1982) argued, the construct of commitment takes longer for it to develop among organizational members than job satisfaction. In addition, a plethora of empirical studies suggests that once a member is satisfied with a job, they have strong intention to stay in the organization. The intention to stay is a basis of organizational commitment. Thus, a causal relationship from job satisfaction to organizational commitment was hypothesized in Model 2. Model 3, however, is also valid in that the longitudinal study of Bateman and Strasse (1984) empirically proved that organizational commitment was the antecedent of job satisfaction.

Along with the empirical results, Bateman and Strasse (1984) and Vandenberg and Lance (1992) argued that employees should adjust their level of satisfaction based on their current level of commitment. Although the statistical difference was not tested, the beta coefficient from organizational commitment to job satisfaction was greater than the beta coefficient from job satisfaction to organizational commitment. However, this was the only support for Model 3. The model fit indices were identical for both models. In addition, the path between organizational identification and job satisfaction was found not to be statistically significant in Model 3. Moreover, SMC from two independent variables in Model 2 and Model 3 also supported that organizational identification and job satisfaction had more explaining power than organizational identification and organizational commitment on their dependent variable. Thus, Model 2 was chosen as the best model that can describe the organizational identification, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment of female professional dancers in Korea. The dancers’ organizational commitment was found to be formed by their organizational identification and job satisfaction.

The respondents recorded relatively high organizational identification (M = 3.96) indicating that they perceived oneness with their dance team. In addition, the uniqueness of dance teams actually could enhance the scores in organizational identification in that they perform together for the success of their team. Compared to a large business organization where a member’s contribution to an organizational success is quite invisible (such as Nike, Samsung, etc.), each dancer who performed on a stage should strongly feel that they contributed to the successful performance of the dance team. Accordant with previous literature that organizational identification is an antecedent of job satisfaction and organizational commitment, the beta coefficients were all statistically and practically significant as well. The dancers’ organizational identification explained 37.2 percent of job satisfaction and 16 percent of organizational commitment. Thus, as long as a leader and the management of a dance team ensures that the members of the dance team share the success and failure of the team, the members’ job satisfaction and organizational commitment is guaranteed to a certain extent.

In addition to the effect of organizational identification, the dancers’ job satisfaction was found to influence their organizational commitment to a great extent. The beta coefficient was .50 and job satisfaction explained 25 percent of organizational commitment among female professional dancers. Since Model 2 was selected to be the best fitting model that can describe the organizational behavior of female professional dancers, it is reasonable to say that they were satisfied with their job and then committed to their dance team. The mean scores of job satisfaction and organizational commitment was higher than median value of three. Also, the job longevity proved that the dancers were quite satisfied with their job and were committed to their dance team. The average length of the membership among women professional dancers was almost six years (M = 71.76 months).

This study was able to provide empirical analyses of organizational identification, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction of a relatively untapped population of female dancers. In addition, this study was able to provide a preliminary outlook regarding the organizational variables in female dominant organization (i.e., dance team) in non-Western culture. As indicated in many previous literature (e.g., Vanaki & Vagharseyyedin, 2009; Wasti, 2003; Yousef, 2002), there has been a lack of empirical research on organizational commitment and key variables in non-Western countries.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although this study investigated the relationship among organizational identification, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment of female professional dancers in the Republic of Korea, a couple of limitations are recognized. First, the generalizability of the results is quite limited. Although this study utilized the data from six different dance teams inside and around Seoul area, this still cannot represent the dancers in other geographic areas in South Korea. Future studies need to collect data from other areas so that the results can have a better generalizability. The second limitation also came from the nature of the sample. The current study was not able to compare the organizational identification, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment in different types of dance teams due to limited sample size. Organizational types are known to influence members’ behavior and attitude toward their organizations. Thus, future research needs to design studies that can compare members’ organizational identification, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment in different types of dance teams. In addition to the types of dance teams, future studies also need to compare organization related constructs between male and female dancers. Previous literature in Asian context indicated that female members of organizations showed lower level of work commitment due to gender discrimination in their organizations (Peng, Ngo, Shi, & Wong, 2008). Considering the female dominance in dance teams, this would not be the case for dance teams. However, a systematic empirical research is necessary for this purpose.

Notes

Notes

Biographical Note: Jin-Wook Han received his Ph.D from the Department of Sports Management at Florida State University in the U.S. He is a full-time lecturer in the Graduate School of Physical Education at Kyung Hee University in South Korea. His research interests include sports consumers’ consumption behaviors and employees’ job attitudes and behavior in a sport organization. He can be reached at hjw5893@khu. ac.kr

Biographical Note: Eunha Koh received her Ph.D from the Department of Physical Education, Seoul National University. She is at the Department of Policy Research and Development, Korea Institute of Sports Science as a senior Researcher. Her research interests include sports policy and governance, cultural studies of sport, and gender relations in sports. She can be reached at ehkoh@sports.re.kr

Biographical Note: Siwan Han received her Ph.D from the Department of Physical Education, Chung-Ang University in Seoul, Korea. She is a lecturer at Chung-Ang University where she teaches sports psychology and measurement & evaluation in physical education. Her research interests include motivation, burnout, and self-regulation in dance. She can be reached at siwanhan@naver.com

References

-

Albert, S., Ashforth, B. E., & Dutton, J. E., Organizational identity and

identification: Charting new waters and building new bridges, The Academy of

Management Review, (2000), 25(1), p13-17.

[https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2000.2791600]

-

Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P., The measurement and antecedents of affective,

continuance and normative commitment to the organization, Journal of

Occupational Psychology, (1990), 63, p1-18.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1990.tb00506.x]

-

Bateman, T., & Strasse, S., A longitudinal analysis of the antecedents of

organizational commitment, Academy of Management Journal, (1984), 27, p95-122.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/255959]

-

Becker, H. S., Notes on the concept of commitment, American Journal of

Sociology, (1960), 66, p32-40.

[https://doi.org/10.1086/222820]

-

Behery, M., & Paton, R., Performance appraisal-cultural fit and organizational

outcomes within the UAE, Journal of American Academy of Business, (2008), 13, p166-176.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/17537980810861501]

- Brayfield, A. H., & Rothe, H. F., An index of job satisfaction, Journal of Applied Psychology, (1976), 35, p307-311.

- Brunetto, Y., & Farr-Wharton, R., Using social analysis of the antecedents of organizational commitment, Academy of Management Journal, (2002), 27, p95-122.

- Choi, E., & Choi, J., The effect of job satisfaction and organizational commitment on skill development effort and dance performance of professional dance company dancers, Journal of Sport and Leisure Studies, (2007), 30, p371-381.

- Choi, S., Mooyongdanjojik’e empowermentwa jojikmolip’e gwangae {The relationship between empowerment and organizational commitment of dance company}, The Korean Journal of Physical Education, (2004), 43, p601-610.

-

Cohen, A., & Liani, E., Work-family conflict among female employees in

Israeli hospitals, Personnel Review, (2007), 38, p124-141.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480910931307]

-

Cole, M. S., & Bruch, H., Organizational identity strength, identification,

and commitment and their relationships to turnover intention: does organizational

hierarchy matters?, Journal of Organizational Behavior, (2006), 27, p585-605.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/job.378]

-

Currivan, D. B., The causal order of job satisfaction and organizational commitment

in models of employee turnover, Human Resource Management Review, (2000), 9, p495-524.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-4822(99)00031-5]

-

Curry, J. P., Wakefield, D. S., Price, J. L., & Mueller, C. W., On the causal

ordering of job satisfaction and organizational commitment, Academy of

Management Journal, (1986), 29, p847-858.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/255951]

-

Dunham, R. B., Grube, J. A., & Castaneda, M. B., Organizational commitment: the utility of an integrative definition, Journal of Applied Psychology, (1994), 79, p370-380.

[https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.79.3.370]

-

Dutton, J. E., Dukerich, J. M., & Harquail, C. V., Organizational images

and member identification, Administrative Science Quarterly, (1994), 39(2), p239-263.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/2393235]

-

Dougherty, T. W., Bluedorn, A. C., & Keon, T. L., Precursors of employee

turnover: A multiple-sample causal analysis, Journal of Occupational Behaviour, (1985), 6, p259-271.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030060404]

-

Elizur, D., & Koslowsky, M., Values and organizational commitment, International Journal of Manpower, (2001), 22, p593-600.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/01437720110408967]

-

Foote, N. N., Identification as the basis for a theory of motivation, American

Sociological Review, (1951), 16, p14-22.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/2087964]

-

Forgionne, G., & Perters, V., Differences in job motivation and satisfaction

among female and male managers, Human Relations, (1982), 35, p101-118.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/001872678203500202]

- Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. J., & Black, W. C., Multivariate Data Analysis, Prentice Hall, Inc, Upper-Saddle River, New Jersey, (1998).

-

Hall, D. T., Schneider, B., & Nygren, H. T., Personal factors in organizational

identification, Administrative Science Quarterly, (1970), 17, p340-350.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/2391488]

-

Herrbach, O., A matter of feeling? The affective tone of organizational commitment

and identification, Journal of Organizational Behavior, (2006), 27, p629-643.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/job.362]

-

Hickson, H., & Oshagbemi, T., The effect of age and the satisfaction of

academics with teaching and research, International Journal of Social Economics, (1999), 26, p537-544.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/03068299910215960]

-

Johnson, J. H., Effects of accurate expectations about sensations on the sensory

and distress components of pain, Journal of personality and social psychology, (1973), 27, p261-275.

[https://doi.org/10.1037/h0034767]

-

Kagan, J., The concept of identification, Psychology Review, (1958), 65(5), p296-305.

[https://doi.org/10.1037/h0041313]

-

Kiesler, C. A., & Sakumura, J. A., A test of a model for commitment, Journal of personality and Social Psychology, (1966), 3, p349-353.

[https://doi.org/10.1037/h0022943]

- Kline, R. B., Principle and practice of structural equation modeling, The Guilford Press, New York, (1998).

- Ko, J. W., Price, J. L., & Muelller, C. W., Assessment of Mayer and Allen’s three-component model of organizational commitment in South Korea, Journal of Applied Psychology, (1997), 6, p961-973.

-

Lee, H., The role of competence based trust and organizational identification

in continuous improvement, Journal of Managerial Psychology, (2004), 19, p623-639.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940410551525]

-

Lee, S. M., An empirical analysis of organizational identification, Academy

of Management Journal, (1971), 14, p213-226.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/255308]

-

Mael, F., & Ashforth, B. E., Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of

the reformulated model of organizational identification, Journal of Organizational

Behavior, (1992), 13, p103-123.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030130202]

- Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J., Testing the “side-bet theory” of organizational commitment: Some methodological considerations, Journal of Applied Psychology, (1984), 69, p372-378.

-

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J., A three-component conceptualization of organizational

commitment, Human Resource Management Review, (1991), 1, p61-89.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/1053-4822(91)90011-Z]

- Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J., Commitment in the work place: Theory, research, and application, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, (1997).

-

Meyer, J. P., Allen, N. J., & Gellatly, I. R., Affective and continuance commitment

to the organization: Evaluation of measures and analysis of concurrent

and time-lagged relations, Journal of Applied Psychology, (1990), 75(6), p710-720.

[https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.75.6.710]

-

Meyer, J. P., Allen, N. J., & Smith, C. A., Commitment to organization

and occupations: Extension and test of three component conceptualization, Journal of Applied Psychology, (1993), 78, p538-551.

[https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.78.4.538]

-

Mottaz, C., Gender differences in work satisfaction, work-related rewards and

values and the determinants of work satisfaction, Human Relations, (1986), 39, p359-378.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/001872678603900405]

- Mowday, R. T., Porter, L. W., & Steers, R. M., Employee-organization linkage: The psychology of commitment, absenteeism, and turnover, Academic Press, New York, (1982).

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H., Psychometric theory (3rd ed.), McGraw-Hill, New York, (1994).

- O’Reilly, C., & Chatman, J., Organizational commitment and psychological attachment: The effects of compliance, identification, and internalization on prosocial behavior, Journal of Applied Psychology, (2008), 71(3), p492-499.

-

Peng, K. Z., Ngo, H., Shi, J., & Wong, C., Gender difference in the work

commitment of Chineses workers: an investigation of two alternative

explanations, Journal of

World Business, (2008), 44, p323-335.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2008.08.003]

-

Porter, L., Steers, R., Mowday, R., & Boulian, P., Organizational commitment,

job satisfaction, and turnover among psychiatric technicians, Journal of

Applied Psychology, (1974), 59, p603-609.

[https://doi.org/10.1037/h0037335]

- Pratt, M., To be or not to be: central question in organizational identification. In A. Wehttern & P. Godfrey, (Eds.), Identity in Organizations: Building Theory Through Conversation, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, (1998), p171-207.

- Riordan, C. M., & Weatherly, E. W., Defining and measuring employee’s identification with their work group, Educational and Psychological Measurement, (1999), 59, p310-324.

-

Rotondi, T. Jr, Organizational identification: Issues and implication, Organizational behavior and Human Performance, (1975), 13, p95-109.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(75)90007-0]

- Scandura, T., Lankau, M., Relationships of gender, family responsibility and flexible work hours to organizational commitment and job satisfaction, Journal of Organizational Behavior, (1997), 18, p377-392.

-

Shamir, B., Calculations, values, and identities: the sources of collectivist

work motivation, Human Relations, (1990), 43, p313-332.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679004300402]

- Spector, P., Job satisfaction: application, assessment, causes and consequences, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, (1997).

- Steer, M., Antecedents and outcomes of organizational commitment, Administrative Science Quarterly, (1977), 22, p46-56.

- Tajfel, H., Turner, J. C., The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of Intergroup Relations (2nd ed.), Nelson-Hall, Chicago, (1985), p7-24.

-

Tuzun, I. K., The impact of identification and commitment on job satisfaction;

the case of a Turkish service provider, Management Research News, (2009), 32, p728-738.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/01409170910977942]

-

Vanaki, Z., Vagharseyyedin, S., Organizational commitment, work environment

conditions, and life satisfaction among Iranian nurses, Nursing and

Health Sciences, (2009), 11, p404-409.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-2018.2009.00473.x]

- Vandenberg, R., & Lance, C., Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention and turnover, Personnel Psychology, (1992), 46, p259-290.

- Van Dick, R., Wagner, U., Stellmacher, J., & Christ, O., The utility of a broader conceptualization organizational identification: which aspect really matter?, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, (2004), 73, p137-147.

- Ward, M., & Sloane, P., Job Satisfaction: The Case of the Scottish Academic Profession, Mimeo, University of Aberdeen, (1998).

-

Wasti, S. A., Organizational commitment, turnover intentions and the influence

of cultural values, Journal of Occupational Psychology, (2003), 3, p303-320.

[https://doi.org/10.1348/096317903769647193]

-

Wiener, Y., Commitment in organizations: A normative view, Academy of

Management Review, (1982), 7, p418-428.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/257334]

-

Yousef, D. A., Job satisfaction as a mediator of the relationship between

role stressors and organizational commitment, Journal of Management Psychology, (2002), 4, p250-266.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940210428074]