Explore Rural Female Elders’ Old-Age-Provision Plight and Solutions

By the Participatory-Need-Assessing and in-depth interviews we began to investigate the current living situation of the rural female elders at five sampled villages scattered in three of the counties or cities in Henan - a province located in Central China with a large rural population. We found a very strange and contradictory phenomenon: “Strong Son- preference” for “Raising-Son-for-Old-Age-Nurturing” VS the “Having-Son-But-Having-No- Old-Age-Provision” Plight. After many participatory discussions with the villagers, we realize that the roots lie in the patriarchic principles, which still directing the rural families. The first is the “patrilineal family succession”, or to carry on the line of the family by following the father-to-son principle; the second is the “son staying in, daughter moving out” marital residency convention, which constraints a married woman being the member of her husband’ familiy but not her native family; the third is the sex-based labor division principle of “men running without, woman within.” These lend to two vicious cycles: “Raising-Son-for-Old-Age-Nurturing” but the “Having- Son-But-Having-No-Old-Age-Provision”, the conflicts for centuries between the daughter-in-law and the mother-in-law. As one feminist action research, we are exploring to break through the patriarchal institution and promote a diversified old-age-provision model, including 1) the family-based old-age-provision such as the son and daughter respectively or united providing their parents, the parents providing themselves; 2) the community-based old-age-provision; 3) the government-based old-age-provision.

Keywords:

rural women elders, old-age-provision plight the rules of patriarchal family a diversified old-age-provision modelIntroduction

Judged by the international standard, China entered its aging period since the end of 1999. It is one of the developing countries that start aging earlier in a pattern that is a lot different from that of the developed countries in the following features: High Speed: there is an annual increase of five to six million gray-haired in its population; Large Scale: it has the largest gray-haired population in the world; Female Outnumbers Male: there are 4.64 million more female elders than their male counterparts; Getting Old before Getting Rich: its social and economical development level is under its population aging pace; Speedier Rural Aging : the rural population ages speedier than the urban. These factors plus the lagged behind social securities and services resulted from the drastic social changes, have turned the aged - especially the rural female aged who are triple-disadvantaged in class (as peasants), age, and sex - into a frail group whose “resources and properties are especially vulnerable” (Moser, 2001).

We have been focusing on rural women elders’ living and old-age-provision issues since 2006 (Henan Community Center for Education and Research [HCCER], 2007; The Gender Equality Policy Advocating Project Team [GEPAPT], 2008). By way of Participatory-Need-Assessing and in-depth interviews we began to investigate the current living of the rural women elders at five sampled villages scattered in three of the counties or cities in Henan – a province located in Central China with a large rural population. Meanwhile, we also initiated intervention researches and community experiments, probing in ways that may help to solve or ease the rural-age-provision problems, especially that of the rural female elders.’

Problems: Strong Son-Preference VS the Having-Son-but-Having-No-Old-age-Provision” Plight

“Strong Son-preference” VS the Idea of “Raising-Son-for-Old-age-Nurturing”: Expectations and Disappointments

Based on an in-depth analysis, Liu Cheng pointed out that the current family planning policy of “One-Daughter-Equaling-to-Half-a-Son” (which authorizes the first baby girl family the right to have a second child) carried out in most of the rural areas is a compromise to the son-preference ideology fostered by patriarchy, and that such a policy has led to a serious gender disproportion in birth rates (Liu, 2008).

In the investigation, we strongly felt such son-preference when talking with the local villagers. What follows is a record of an in-depth and frank interview conducted in a village in August 2008:

Question: If your first child were a girl, would you have a second child?

Answer: Absolutely! I would pay a punishment for the second child even if there were no birth quota.

Question: Would you take the Ultra-sonic B (UB) to make sure the second child be a boy?

Answer: If the first birth is a boy, UB is seldom taken for the second birth, for either will be fine. But if the first birth is a girl, only lunatics would skip the UB detection for the second birth.

Question: Is there anyone who has a baby girl (fetus) aborted?

Answer: Many do! Some had four or five abortions (in succession) after UB detecting just to make sure that the second birth be a boy. (GEPAPT, 2008)

Why is having a son so important for the villagers? In the participatory investigating, the villagers listed out four reasons: to continue the family line, secure old-age-provision, do physical labor, and earn a living for the family. We found that the notion “to secure old-age-provision” is quite popular (96% in agreement), second only to “continuing the family line” (100% in agreement). But what makes the peasants attach such importance to a son for their “old-age-provision?” What we found goes as follows: first, family-based-old-age-provision is still dominant in most of the less developed Rural Central Region, where social old-age-provision is almost nil in rural communities; secondly, the so called family based old-age-provision really means “son-dependent,” for the “son-stay-in, daughter-move-out” marital residing tradition does not offer any other alternatives.

But a very strange and contradictory phenomenon appeared when we tried to help the villagers further analyze the above mentioned reasons in details: on the one hand, the villagers almost all agreed that to have a son is a store for old-age-provision, but on the other hand, their comments on the performing of such notion are quite negative and full of dissatisfactions. The villagers remarked:

“To rely on the son for old-age-provision? He is a filial son that won’t beat you or yell at you!”

“The filial sons take up 15% at most, the unfilial ones 30-40%.”

“It will do well for one man to feed a number of children. But it won’t work the other way round. Having more sons means less provision for the old.” (GEPAPT, 2008)

The Chinese idea of “filial piety and nurturing-the-aged” can be traced back far into the traditions and was strictly regulated. Unfortunately, even though the aged have lowered their filial expectations to “not beating or yelling at the elders,” those who are up to the standard are still a small number. What is more subversive is that most villagers agreed on the saying “more sons means less provision for the aged.” That has entirely overturned the notion of “having more sons for more happiness.”

The Current Old-age-Nurturing in the Rural Areas

Do the low evaluation and high expectation on the son-dependent old-age-provision give a true picture of reality? Our in-depth investigation proves that the living conditions of the rural elders (especially that of the women rural elders) are wretched. We may say that these people are threatened with a general old-age-provision crisis today.

We need to make some necessary definitions to the concept of “the aged” based on the reality of China’s rural areas before focusing on the issue of old-age-provision crisis. It is better to define the 45 to 60 age group as the “sub-aged elders,” considering the fact that some people may have their grandchildren in mid-forties, though still young, they are the “elder-generation” in the family; age 60 is the first borderline for old age. According to the majority of the villagers, one is getting old when entering age sixty. But this group of people do not need others’ care unless they fall ill; those do need “cares” are the senior-aged, sick, and widowed. Therefore, we can discuss old-age-provision at three age levels: the ordinary elders (age 60-75), the senior-aged who need care (above age 75), and the sub-aged (under age 60) who are going to be nurtured. Additionally, health is also an important index in determining whether one needs care or not. Some people can still work in their 80s and do not need others’ provision.

The Ordinary Elders

Residing: generation-based family split. To live with one’s father, to take his family name, and to carry on the family line used to be the significant features of patriarchy. Nowadays, the first feature has changed drastically though the latter two still remain the same in practice. In the rural areas of Central China, more than 80% of the elders live separately from their married sons. Some may live in the same courtyard, but their family resources and properties are divided. What is more, their cooking and eating are also done separately. The elders describe such generation-based family split pattern in their own words as follows: the old couple living on their own is called the “living alone” pattern; while living with their son and daughter-in-law is termed as the “living-on-son” pattern, which reveals the passive, powerless dependency of the elders.

Laboring: heavily burdened with labor till they get too old to move about. The majority of the elders not only manage to earn their living by their own efforts, but also try their best to help their children and take care of their grandchildren. These elders describe their situation, as “it is never too old to labor.” Women elders are the most back busting of all as they are burdened both physically and psychologically. Apart from field farming, they are also engaged in washing, cooking, poultry and livestocks raising, etc. Many of the women elders have to take care of their husbands, who, on the contrary, can spend their spare time chatting and recreation.

Living: maintaining a low-level living of dressing warmly and earring one’s fill. The elders are usually the ones who eat the worst food, having the poorest dress, and living in the shabbiest houses of the village. The doggerel popular in the rural area describes the situation vividly:

My son lives in a tile-roofed house and his son in a villa,

When their old mom and dad are left in the shabby cottage.

My son cooks with coal and his son with gas,

When their old mom and dad have to collect firewood for cooking.

My son has wheat and his son rice,

When their old mom and dad take corns to appease hunger...

(HCCER, 2007)

The elders’ spiritual life is no better. They are found in general loneliness, and badly in need of family empathy. Increased age often comes with frail health. This plus a usual shortage in public life makes it all the more necessary for the rural elders to draw concerns and cares from their family members. But such desire for family empathy can hardly be satisfied with their married daughters moving out to the in-laws’ villages and their sons doing migrant jobs in cities (sons seldom communicate with their parents even if they stay in home). Things get worse if conflicts arise between the in-law females (namely the mother-and daughter-in-law). Generally, male elders will not get involved in the “inner family affairs” or emotional imbroglios. Considering the fact that men usually live a shorter life than their wives. So women elders are all the more likely to be trapped in weary loneliness.

The Senior-aged that Needs Nurturing and Cares

The old-age-provision is particularly a problem with three kinds of elders: the senior-aged, the widowed and the sick (many of them are women elders). The social old-age-provision facilities in the rural areas such as the nursing houses, are primarily provided to the “Household enjoying the five guarantees (wu bao hu 五保戶)” (childless families and infirm old persons who are guaranteed food, clothing, medical care, housing and burial expenses). Elders with children mainly depend on family supports for old-age-nurturing. Those who are unable to work or take care of themselves as consequences of senior-age, widowing or diseases will resort to the following patterns:

Nurturing in turn: such pattern means the elders will stay (or “eat”, to be more exact) in each of his or her son’s homes in turn. Each son is to provide the elders (with three meals a day) for a certain period of time. (Usually the cycle is set at seven to ten days, fearing that a longer cycle may lead to disputes). Most of the nurtured in turn are widowed women elders. Such arrangements can ensure them to have adequate food and clothing, but often they feel hurt psychologically. Sometimes, such in-turn nurturing may put the elders’ lives in risks. In an extreme case, a seriously ill woman elder died in shuttling from one son’s home to that of the other’s.

Separate Nurturing: such arrangement forces the old couple to live separately so that their sons and daughters-in-law may be less burdened when one family has to provide with only one of their parents. Some young couples forbid their parents to see each other just to make sure that their mom and dad will make no comparison of the food served or give out what one family has to his or her spouse - the one that is supposed to be fed by another family. One married woman in her middle ages told us:

“My parents are nurtured separately by each of my elder brothers. They won’t allow them to see each other so that my parents cannot compare what food is served! My mom complained: your dad and I are faced to be ‘divorced’ by our sons!” (GEPAPT, 2008)

Cases concerning old-age-nurturing or elder abuse are often heard of in rural areas. The more sons a couple have, the more likely they will get into old-age-provision disputes. In recent years, such cases take up 90% of all the old-age related cases. Many of the elders who are abused, beaten, abandoned, or even forced to commit suicide are widowed and sickish women. But, even the handicapped elders are unwilling to adopt the law in protecting their rights and interests out of consideration of “mianzi (面子 face)” or family ties. Their usual way is to “ask the village cadres to make a judgment”. But now, many people will just stand by with the excuse of non-interference of other’s private life. The village cadres are no exception. Their strategy is to avoid it, assuming that “it is a tough but thankless job to meddle into other people’s family affairs” (HCCER, 2007).

Mid-aged Elders: “the Sub-aged”

In the interviews we found that the sub-aged healthy elders (fifty-sixty years old) are filled with worries or even fears of their senior-aged future, though they are not yet handicapped in waiting for other’s care and provisions. Such worries or fears are neither caused by the low birth rates (these elders have at least two or more children), nor entirely by poverty (they have no problems in maintaining a life of adequate food or clothing). Further communication indicates that their worries and fears are mainly resulted from their feeling of “insecurity” for the senior-aged life to come. The feeling of economic insecurity comes on top of everything else. Building houses for their sons to get married, paying for the wedding with their annuities, these elders spent all their lifetime savings for their sons. Now with empty hands they have no other choice but to leave their old-age-provision at the mercy of their son(s)’ for they have lost the ability to handle any unexpected incidents. Psychological insecurity comes second: with the married daughter living far away in her husband’s house, the elders can find nobody to pour out their hearts to; it is true that the daughters-in-law are within reach, but the tense relationship makes it easy to get into disputes. In our interviews, whenever the topic was switched on the in-law relation, the mothers-in-law, who were talking cheerfully and humorously a minute ago, would stammer and hesitate, just uttering brief answers like “fine, good.” Obviously they were afraid of causing troubles (HCCER, 2007).

Probe in the Ultimate Causes of Old-age-Provision Handicaps

Whatever the problem is, be it the general living difficulty confronted by the senior-aged women in residency, labor, life, health, and emotion, or the old-age-nurturing crises that are threatening the senior-aged, sick and widowed elders who are badly in need of cares, or the “insecurity worries” that are torturing the sub-aged elders, we must trace down to the roots of these problems. Through the villager-participatory discussions, we finally come to see that the roots are lying in the patriarchic principles still working in the rural families: the first is the “patrilinear family succession,” or to carry on the family line by following the father-to-son principle; the second is the “son staying in, daughter moving out” marital residency convention, which rules that the married woman is a full member of her in-laws’ family; the third is the sex-based labor division principle of “men running without, woman within,” which demands women to shoulder the primary responsibilities in taking care of the aged and the sick.

“The Father-to-Son Family Line of Succession” and the Notion of “Raising Sons for Old-age-Provision”

Some scholars pointed out that patriarchy is declining in rural Chinese families (Jin, 2000). Our investigation in the rural Central Region indicates that, on the one hand, the paternal authorities do decline obviously in their kids’ selection of a spouse, residence, and in property divisions. But on the other hand, the fundamental working principles of the paternal family continue to run as before - that is, the family lineage must be carried on by sons. Without a son the family link will break and stops running. “Succeed the family lineage” is set as a man’s cause and goal of a life commitment (Fei, 1998). It will be the greatest tragedy for a man’s life and for his family if he fails to succeed the lineage. That is why curses as “may you be the last of your line (duanzi juesun 斷子絶孫),” or “may you die sonless (juehutou 絶戶頭)” are considered the most vicious in the rural regions.

Marriage is to guarantee the smooth running of the paternal family. To get a wife for the son, who, in turn, will give birth to his sons, in this way, the family will run on for generations; when a daughter is married, her duty is to bear sons for her husband’s family to succeed the line. So the daughter-in-law with no kin relation is a full member of the in-laws’ family, whereas the daughter with close kin relation is but an “outsider”. The so-called “raising sons for old-age-provision” really means “to get a wife for reproduction (quqi weiyang 娶妻爲養)” as described by Mencius (n. d.). The parents have to rely on their sons and daughters-in- law for cares and provision when getting old. They do not seem to have much choice. Confined to the patriarchy and conventions, many elders just do not know how to find a way out when trapped in the difficulties of “having sons but having no one to provide cares and nurtures.”

“Son-Succeeding” and “Property-Transferring”

The economic principle in the paternal succeeding system demands that the inherited family resources and properties be passed on to the son/s, then to the grandson(s). If there are two or more sons in a family, all the inherited stuff must be “divided evenly among the sons”. Such inter-generational property-transfer usually starts at the son’s wedding preparations: building a house for the newlywed, running the wedding, the parents of the bridegroom have to pay for all the costs, which mean big money. All the villagers agreed that their sons’ marriage costs are the heaviest burden in their lifetime. What follows is the accounting made by the villagers: Housing and furniture: 150,000 RMB; Wedding preparations: 20,000 RMB (including gifts for the first meeting, engagement, betrothal, purchase of dressing and quilts for the bride) ; Wedding day cost: 30,000 RMB (including gifts for the bride to get off the car, to call the in-law mom and dad, for the escorting, wedding feast, and for those who help to see off the visitors).

Counted on the per capita income in the rural Central Region, the bridegroom’s parents have to toil for over 30 years and keep away every penny before they can hope to get enough savings to “cover a son’s marriage”. The elders exclaimed that:

“House building and wedding, the costs of one son’s marriage will bleed white his old man. Such burden is as heavy as Mount Tai!”

When a son is to get married and embark on a career, he has kicked off the process of nibbling his parents’ resources and properties. Having more sons means heavier burdens for the old. When the youngest is to get married, what his parents can do is to refurbish the old house - the last of the family property - for the newlywed. By then, the old couple is penniless in the real sense. Those who have not spent all their savings in the process must evenly distribute what they have had among their sons again, at the time when they are getting too old to work. The second distribution is regarded as the previously paid fees for their old-age-nurtures. Having all their properties transferred to their son/s, the old couple is now “dependants.” They must rely on their son/s for care and provision. The loss of economic independence also takes away one’s sense of security. Often than not, the even property distribution among sons ignites nurturing disputes. Eight out of ten of the sons involved in such cases complained that their parents were unfair in dividing the properties. Everyone claimed that he suffered losses, while no one was willing to do a bit more for their parents. Seeing that, their aged parents could only “grieve over” their “lost resources and properties”.

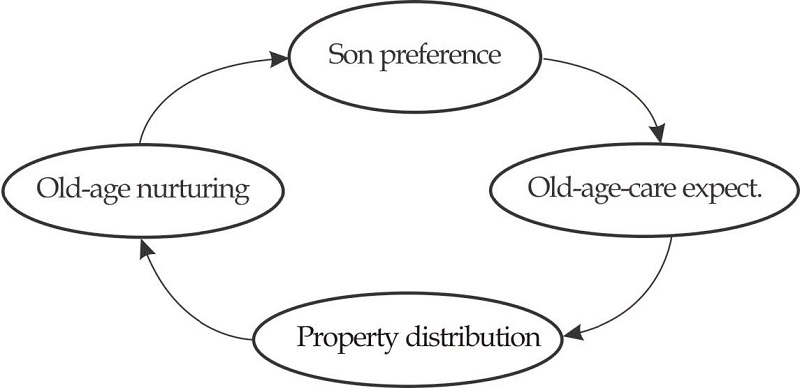

The “son preference” is an idea resulted from the “carrying on the family line” intention. In reality, it can be translated into an expectation of having sons to secure old-age provisions. When a son gets married, his parents begin to transfer to him the family belongings until they become penniless. When getting too old to work, they are trapped in the old-age difficulties. Ironically, the grandsons and great grandsons just follow suits of their parents, and none could get out of the vicious cycle:

The villagers see such cycle clearly, but how to get out still needs exploring.

Marital residency, sex-based labor division and the “female in-laws’ conflicts”

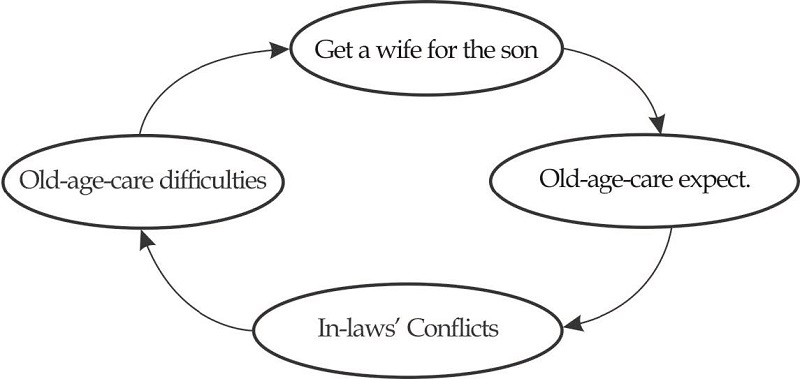

What follows is the other vicious cycle responsible for the old-age-provision difficulties:

It is the parents’ life responsibility to see that their son(s) get married. But at the same time, parents also expect their son(s) and daughter(s)-in-law to provide them for their old ages. But the idea is facing great challenge now: the conflicts between the in-law females are getting acuter in the rural Central Region, greatly affecting the life quality of the women elders. Some villager described the problem in an exaggerating comparison: “The conflicts between the in-law females are like that between the enemies” (GEPAPT, 2008).

The female-in-laws’relation has been a problem for hundreds of years. Judgments made on such a problem have never gone beyond the interpersonal conflicts between the two women involved. In the era when “marriage were arranged by parents,” criticism tended to target the “atrociously oppressive mother-in-law” then the condemnation switched to the “vicious daughter-in-law” when the authorities of the former declines with the descending patriarchy. However, when examining the female-in-laws’-relationship from the perspective of feminism, we can see that the so called in-law conflict is not a war involving two women, but a fast knot formed in the patriarchic family. The paper hereafter will examine it by way of gender analysis:

First of all, the marital residency rule demands a married woman to live in her husband’s house and become a member of the in-law family, whereas her own parents to whom she owed her life and nurturance are turned into some “alien outsiders.” It is her duty to look after her in-law’s family. But her heart and empathy will go to her own family. Confined to her in-law-family-member identity, she has to either give less cares and supports to her natal family, or doing the care under covers. Such unequal demands can easily lead to psychological unbalance that may be brewed into an impulsion against her in-law family members (especially her mother-in-law). That is how a mother’s “filial daughter” is turned into a “vicious daughter-in-law” after marriage.

Second, a reality is covered by the sex-based labor division of “man running without, women within” : the so-called “son-dependent-old-age-provision” is only a name. The caring is done not by the son but by the daughter-in-law. “Taking care of somebody” is forever regarded as women’s share of work. Looking after the old and the sick in the family is considered the daughter-in-law’s unconditional duty. The sons are not required to do the specific caring for their parents. One male villager told us that he once washed a coat for his father. His behavior became a laughing stock at the village. “What did you get a wife for?” So the others mocked him (GEPAPT, 2008).

We need to clarify that “taking care of somebody” is not ordinary work. It is a work demanding great physical labor, strong sense of duty, and a lot of mental efforts. Those engaged in such work for long tend to get nervous under the stress. They become nagging, irritable, and pessimistic. These symptoms are seen more obviously on the reluctant-carers (i.e. the daughter-in-law). Daughters-in-law become the easy targets of criticism because both the society and family take it for granted that “it is a daughter-in-law’s duty” to look after her parents-in-law. No one is considerate of their hardship for being carers. When they try to give vent to their inner dissatisfaction and stress by complaining and getting angry, they sure will run into conflicts with the cared.

As the above analysis indicates, the patrilinear family working rules have led to three problems. First, the father-to-son succession line and the exclusion of a married daughter from her natal family make the “son-dependent-old-age-nurturing” the only choice of the aged. Secondly, the “son-inheriting-family-property-at-marriage” rule takes away the elders’ economic independence way back too early. Thirdly, the “living-with- husband’s-family” marital rule and the sex-based labor division of “men running without, women within” can easily ignite disputes and conflicts between the in-law females. In a word, patriarchy is the root cause to rural elders’ difficulties in obtaining basic old-age-nurturing such as economic provision, life care, and spiritual solace.

Additionally, the commonly existing collective patriarchy in rural communities has helped to continue and enhance patriarchy within the family in a collective unconsciousness, thus pricking up rural elders’ old-age-nurturing handicaps. Our research finds that almost all the “Village Rules” are drafted on the “son-staying-in, daughter-moving-out” marital residency principle in referring to the distributions of collective resources such as the setting of house-plot and responsibility land, land compensations, and collective welfares, etc. The village rules refuse to let a married woman to stay in her parents’ village, forbidding the divorced or widowed woman to move back to her natal village for settlement, and allowing the son-less family only one quota to marry in a son-in-law. The state policy of Household Land Responsibility, claiming unalterable for 30 years, really protects the interests of the male peasants whose residency remain unchanged for generations. But such a policy makes many women lose their land because of the marital residence rule. When the land-lost women went to the government for help and supports so that they could protect their legal rights, the relating departments simply turned them down with the excuses of “following the public opinions” or “for the village stability.” It is acquiescing the Village Rules to abuse women’s rights.

As a consequence, the patriarchical rules that have been running for thousands of years are inherited, solidified, and enhanced by the interaction of the family system, village rules, and state policies, thus forming an institutional obstruction in solving the rural (especially female) elders’ old-age-nurtures.

Activist Research - Probing Breakthrough in Solving the Old-Age-Provision Handicaps from the Feminist Perspective

Up till now, almost all the existing old-age-provision designs and patterns have regarded raising social old-age-provision level as the best or even the only-way-out, but hardly thought of solving/relieving the problem by trying to change the patriarchic rules. Their reasoning is built on the belief that the rural old-age-provision will be solved with the construction of nursing houses in rural communities or with the promulgation of endowment insurance. But we must see the fact that, confined to China’s economic and social development levels, establishing rural old-age nursing facilities or setting a rural endowmentinsurance coverage are only ideas for the time being. Besides, even the time comes when socialized old-age-provision level is greatly raised, family-based-old-age- provision still can play an irreplaceable functioning. The UN Laws for the Aged drafted in 1999 requires that: “it is better that the aged stays in home as long as possible.” That is an emphasis on the advantage and irreplaceableness of the family-based-old-age-provision (Hong Kong University, 2004).

Another consideration is to tackle the issue by advocating the traditional Chinese virtues of “filial piety.” As a matter of fact, governments and press media have adopted many ways to encourage such virtues, for example, serial pictures on filial acts are drawn on the walls of many villages. But such propaganda may still have problems. First of all, the acts traditionally praised (Dong Yong selling himself to get his deceased father buried; Guo Ju would bury his son alive just to get food for his mother’s provision, etc.) are real hard for the ordinary people to follow suit. Secondly, many of the ideas illustrated in the pictures are in essence closely linked with patriarchy. What embodied in the Book of Rites, “Repairing of ancestral temples and reverential performance of sacrifices intend to guide the people to follow their dead with their filial duty”are similar to the idea of Mencius, “there are three things which are unfilial, to have no posterity is the greatest of them”. All the ideas focus on that the greatest “filial duty” is to maintain the succession of the family line. Apparently, it is improper to just depend on advocating “filial duty” to solve the old-age-provision handicaps. What’s more, such advocating has the danger of turning the old-age-provision - a social problem - into a family problem, then further into a moral problem. That is a move against the time. We should stay alert, and prevent the “filial duty” advocating from further enhancing the awareness of “succeeding the family lineage.”

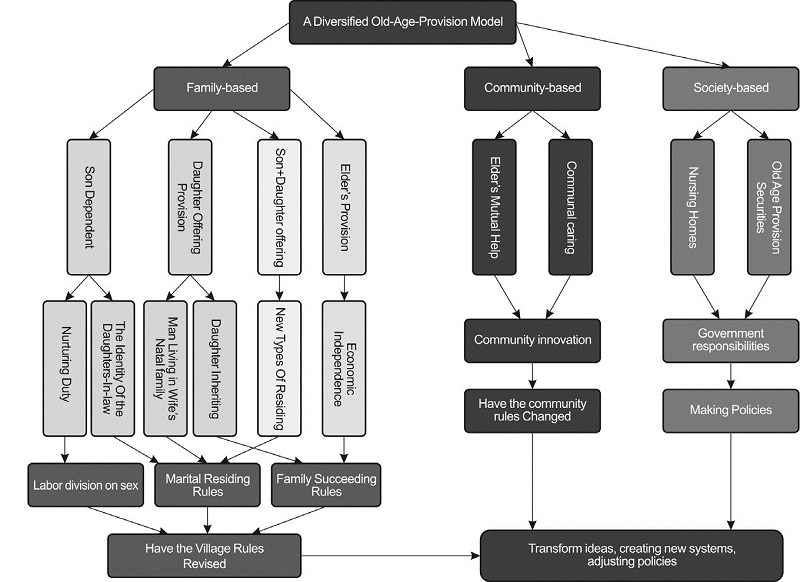

What we are trying to do is to probe ways to break the institutional patriarchic obstructions from the feminist perspective, promoting a diversified old-age-provision model. Since 2008, we have started our probe in the rural Central Region of China. Sticking to the activist research method encouraged by feminism, we worked with the local villagers in making community experiments on the possibility of a diversified rural old-age-provision model. The work done in a year and a half has helped us to gain some initial understanding on how the diversified model may work well. Presently, we are just feeling around in trying to generalize such a model.

Family-Based Old-Age-Provision: “New Wine” Put in the “Old Bottle”

As mentioned above, family-based old-age-provision will remain a dominant pattern in the rural regions for quite a long time to come. But a diversified model ought to replace the singular son-dependent-only pattern.

Son-Dependent Old-Age-Provision: Changing the Old Gender Rules

Considering the rural reality, we have to admit that the married couple living in the man’s house will continue to be the main trend and the son still shoulders the prime responsibility of parents’ old-age-provision. But new stuff should be added to it:

First, the identity of the daughter-in-law should not be defined by her marital residence. By that we mean she is an independent person rather than a member of her in-law’s family, or her parents’ family. Being a daughter, she also shoulder the responsibility of tending her parents. In fact, the state laws have confirmed the responsibility for a long time. It is the folk law that has followed the patriarchic tradition and defined daughters as the “outsiders” of their natal family. One solution is to legitimize and make open the daughters’rights and responsibilities as “folk-leveled promises,” so that they can give care and supports to their parents with justice on their side.

Secondly, “care-taking” should not be taken as women’s “patent”, it ought to be shared by both man and woman. The man shall shoulder up the substantial nurturing responsibility to his parents as a son, and at the same time, he shall also give psychological, moral and justice supports to his wife, who does the actual caring and nurturing work.

What has to be emphasized is that, the above-described two points are not just “tactics”, but a challenge to the old gender rules (for example, the son staying in and daughter moving out marital residing rule, the sex-based labor division). If put into practice, they can ensure the daughter-in-law’s rights and effectively improve the female-in-law’s relationship.

Daughter-Offering-Old-Age-Provisions: Equity in Responsibilities and Rights

In our opinion, the “daughter-offering-old-age-provisions” differs from the “daughter-taking-care” pattern in that, the former refers to a daughter’s legal responsibility in offering old-age-provision while the latter defines a daughter just as a nurturer. What we advocate is the former. As a matter of fact, daughters are taking the responsibilities of caring for the old in the name of the son-dependent-old-age-provision pattern now. Many rural elders rely more on their daughters for caring and spiritual solace. It is the living-in-husband’s-house rule and her identity of being a member of the in-law family that make it inconvenient for a daughter to give care and provisions to her parents. What we need to do and can do is to get the village rules revised, canceling the compulsive marital items, and adding the ones that will protect women’s legal rights in selecting their residence after marriage, thus creating favorable environments for daughters to take the responsibility of old-age-provision. The village-rule-revision done at Zhoushan village in Daye Township of Dengfeng City has provided us with a successful case (GEPAPT, 2009).

We need to point out that rights and responsibilities are equivalent and indiscerptible. The one with rights must take responsibilities. Similarly, the one taking responsibilities ought to enjoy the relevant rights. So when the daughters’ responsibilities in offering old-age-provision are set, the “secret rules” that working in the paternal family should also be revised so as to ensure that daughters and sons have equal rights in succeeding the family properties.

Son + Daughter Pattern: Creating A New Marital Residing System

With the rise in child-cultivation costs and changes in people’s reproductive ideas, the number of children in a rural family is declining. One-child family is on the rise. “living in husband’s house” or “living in wife’s house”, neither suits the needs of the one-child families. Creation of flexible and diversified marital residing patterns is imperative under the situation. In real life, the villagers have found some countermeasures by themselves. For example, the “shuttling” pattern in Yidu, Hubei Province, and the “rotation” pattern in the south of Jiangsu Province are the rural people’s own innovation –both can be interpreted as the “no marrying in or out” principle. The married couple can choose to shuttle between either parents’ house according to the elders’ needs, or they can live in either parents’ house in turn. Based on family needs and individual choice, such flexible marital residing pattern will add some modern and harmonious aura to the traditional family-based-old-age-provision.

Elder’s-Self-Provision: Ensuring of Self Dignity and Security

The “elder’s-self-provision” Pattern emphasizes the elders’ economic ability in self-provision. Whatever the old-age-provision pattern, the elders’ complete economic dependency on their son or daughter ought to be changed. To realize that the family property distributing rules must be changed first. The “giving everything to the son(s)” principle should be replaced by the “keeping something for one-self” principle. Preparation for old-age-provision should be made in one’s mid-age. The elders with money in hand will have the liberty to choose the kind of old-age-provision according to their own will. They can choose to be taken care of by their son/daughter-in-law, or by their daughter/ son-in-law, or simply go to the nursing house. Anyway, only the economically independent people can make choices and have dignity, and only with dignity can the aged be ensured of a quality life.

Communal Old-Age-Provision: Respect and Support the Peasants’ Innovations

Communal old-age-provision is something new in the rural areas. It is created by the villagers and village leaders in consideration of the needs and real situations. Some of the rudiment patterns are working as follows:

(1) Mutual-Assisting Group: it is formed on the principles of free will and nearby residency. In such groups, the not so old take care of the senior aged.

(2) Shared Nursing: elders from several empty-nest families will hire one nurse to take care of their life. The families sharing the payment are less burdened economically, but mutual assistance among the elders is necessary.

(3) Signing a tilling-for-old-age-provision agreement with the landless: with village leaders’ help and supervision, let the landless (or the moved-in son-in-law) sign a “tilling-for-old-age-provision agreement” with the empty-nest elders whose children are out working. By the agreement, the landless villager will farm the elder’s land, and the land income will be divided evenly between the two families.

(4) Designing residence suitable for two or four families to live together in the campaign of the “new rural communities construction”, thus bringing into full swing the rural communal advantage in close interpersonal links by encouraging the neighbors to offer “mutual help and spiritual solace in production and housework.”

Whatever the method adopted, we need to see things beyond the economic lever and constantly probe in new perspectives. In facing the impacts of markets and urbanization, we must stick to the “urban-rural equivalent” principle and try to find ways fit for the rural elders’ old-age-provision based on the rural advantages.

Social Old-Age-Provision: Government Assuming the Responsibilities

The social old-age-provision securities in China have never covered peasants due to the urban-rural-separated dual system. Nowadays, the problem is hopeful to be settled gradually. The C.P.C Central Committee No. 1 Document in 2009 put forward “the new social securities of individual pay plus collective and government subsidies for rural old-age-provision.” Such program kicked off its experiments in aiming to construct a mature rural old-age-provision system at large (the Central Committee of the C.P.C & the State Department of the PRC, 2009). The document states clearly that the government will partly take direct responsibility of the peasants’ old-age-provision. We must admit that is a significant breakthrough although the work has just begun, and “its moulding may take decades of time” (Guo, 2009, February 14). In the process of its development, an increased number of rural elders will draw benefits from it.

We believe that the handicaps of the rural elders (especially the aged women) can be effectively relieved by promoting a diversified old-age-provision model based on family, community and society (See the following illustration).

Promoting a Diversified Old-age-provision Model, Beyond the Vicious Cycle of the Old-aged Difficulties

We firmly believe that, with continuous hard work, the diversified model not only can break the present handicaps in rural old-age-provision, but also shake and change the structure of the paternal family and community. Moreover, the model can serve as a key cut-in point in the current new-countryside-construction program, for it can both satisfy the rural women elders’ practical and strategic gender needs.

References

- Central Committee of the C.P.C & the State Department of the PRC, (2009), Opinion on Promoting Steady Agricultural Development and Continuously Increasing Peasant’s Income in 2009, Central Committee of the C.P.C & the State Department of the PRC.

- Fei, X. T., (1998), Rural Regions in China, Beijing University Press, Beijing.

- Gender Equality Policy Advocating Project Team, (2008), Grassroots Survey Report, Unpublished manuscript, Women’s Studies Center, Party School of the Central Committee of the C.P.C.

- Gender Equality Policy Advocating Project Team, (2009), Quiet but Profound Changes - On the Spot Record of the Zhoushan Village Rules Revision, Henan People’s Publishing House, Zhengzhou.

- Guo, J. J., (2009, February, 14), Speech presented at the First Forum on Let the Peasants Get Rich.

- Henan Community Center for Education and Research, (2007), Survey Report on Rural Women Elders’ Living in Central China, Unpublished manuscript, Henan Community Center for Education and Research.

- Hong Kong University, (2004), Theories and Practice of Gerontics, Social Sciences Literature Publishing House, Beijing.

- Jing, Y. H., (2000), The Declining Patriarchy - Gender Studies on the Rural Modernization in the Region South of the Yangtze River, Sichuan People’s Publishing House, Chengdu.

- Liu, C., (2008), Son-Preference and Gender Analysis on Family Planning Policies, Unpublished manuscript, Women’s Studies Center, Party School of the Central Committee of the C.P.C.

-

Moser, C., (2001), The Asset Vulnerability Framework: Reassessing Urban Poverty

Reduction Strategies. In Y. X. Ma & H. J. Kang (Eds.), Translation Collection

on Gender, Ethnicity and Community Development, Chinese

Books Press, Beijing, p90-91.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(97)10015-8]