Creating Their Own Work-Life Balance: Experiences of Highly Educated and Married Female Employees in South Korea

Abstract

South Korea is known as a country with a large number of highly educated women; however, it is also known as a country with the lowest employment rate of female college graduates among the OECD nations. Underlying the low employment of women, there is a phenomenon of a high percentage of Korean women whose careers have been interrupted due to marriage, pregnancy, and childbirth. As a result of unfavorable conditions at both work and home, the number of single women has increased in Korea, and married female professionals also hesitate to have children. This is evidenced by the low birth rate in Korea. The critical need for quality of work life and work-life balance is prominent in Korea. The purpose of this qualitative study was to explore the experiences of the highly educated and married female Korean employees regarding work-life balance. Phenomenological interviews with sixteen participants revealed valuable insights into how to promote the quality of the career women’s lives in the Korean context.

Keywords:

work-life balance, phenomenology, highly educated and married female employee, South KoreaIntroduction

South Korea (Korea) is known as a country with a large number of highly educated women. Since 2009 when the percentage of female students (80.5%) who advanced to college exceeded male students (79.6%) in Korea for the first time, females have outnumbered males in Korean colleges (Cha, 2015). In 2015, the percentage of female college graduates between the ages of 25 and 34 was reported to be 72% while the male counterpart was 63% (OECD, 2015b). This fact reflects not only Korean women’s strong desire for higher education but also a new demographic of a highly educated workforce for the future. Despite the increase in the number of highly educated women, the employment rate of Korean female college graduates ranked the lowest (60.1%) among OECD nations with the widest gender gap of 29% points between male and female graduates in employment rate (Yonhapnews, 2013).

The ineffective utilization of women’s human capital is closely associated with the number of career-interrupted women in Korea (Ministry of Gender Equality & Family, 2014). According to a 2014 survey, 58% of the female respondents (5,854 married women aged 25-59) reported experiencing a career interruption due to marriage (63.4%), childbirth (24.7%), child-rearing (5.9%), and caring for family (4.9%). As the career interruptions mostly occur for Korean women in their early years of marriage or child-rearing, their late twenties and early thirties are considered the most vulnerable periods for their careers (Ministry of Gender Equality & Family, 2014). These women usually re-enter the labor market in their mid-forties when their children attend elementary schools. This career pattern can be graphically illustrated by an M-shaped curve, which is known to only occur in Korea and Japan, compared with Western developed countries where women’s career pattern is a reverse U shape (Han, 2012). When re-entering the workforce, the majority of women tend to be offered temporary employment or lower-level positions than they held before (Oh, Kim, & Uhm, 2012). For highly educated Korean women, their career pattern is reflected by an L shape—meaning no more careers after interruptions. These women give up seeking jobs after realizing that the chance for them to find positions comparable to what they held before is slim (Ministry of Gender Equality & Family, 2014).

Under these unfavorable conditions, more Korean women hesitate to get married; and when they are married, they tend to delay having children. This social phenomenon has exacerbated the low-birth rate (1.24 children per woman in 2015) in Korea (Statistics Korea, 2016a). On the other hand, a rapidly aging population has become another critical concern to the Korean government. In 2015, the number of Korean people aged 65 and above accounted for 13.1% of the total population (Statistics Korea, 2016b). Due to a low fertility rate and a rapidly aging population, it is projected that Korea will likely experience serious labor shortages in 2050 or sooner (Seo, 2013).

To address these issues, the Korean government has resorted to the utilization of a female workforce as a potential solution. To attract women employees, a variety of family-friendly policies (e.g., paid maternity leave, child care subsidies, and the establishment of public daycare centers) have been developed at the national level and promoted to large companies or public organizations (Oh et al., 2012). The government has paid attention to empirical evidence revealed by work-family studies and has planned to formulate work-life balance (WLB) policies. However, most of the work-family studies on the causes of work-family conflicts, the effect of flexible workplace arrangements, and working mothers’ WLB experiences were conducted in the Western context, which has strikingly different characteristics of family, industry structure, and organizational culture (Bailey, 2011; Lee, Chang, & Kim, 2011; Supple, 2007). It remains unclear how the differences between the western and non-western contexts influence married women’s experiences with work-life balance. To enrich our understanding of this issue calls for more investigations into WLB as perceived and experienced by married female employees in contexts different from the west.

This qualitative study is an attempt in this direction. It focused on exploring the highly educated and married female employees’ (HEMFE) WLB experiences in Korea. Highly educated females are women who have attained tertiary education (OECD, 2015a). Following this prevailing criterion (Lee & Park, 2017; OECD, 2015a), we defined the highly educated females for this study as women who have earned a bachelor’s degree or above. One overarching question guided this inquiry: What are the lived experiences of the highly educated and married female employees with work-life balance in Korea? In the next section, we provide theoretical perspectives that informed our understanding of the phenomenon under study.

Theoretical Context

In this section, we start with a brief overview of WLB literature in general. We then discuss this concept specifically in the Korean context. We also present the theoretical frameworks that guided this study.

Work-Life Balance in General

Work-life balance (WLB) is a global issue that has received ample attention worldwide. Scholars have attempted to conceptualize WLB from multiple perspectives. For example, Greenhaus, Collins, and Shaw (2003) argued that in order to achieve a balance, individuals must engage equally in their work and family roles, both psychologically and physically. Similarly, Clark (2000) perceived WLB as one’s psychological satisfaction and good functioning in both spheres based on a minimum of role conflict. Chang, McDonald, and Burton (2010) understood WLB in terms of “harmony or equilibrium between work and family domains” (p. 2382). Despite the varied conceptualizations, it is generally agreed that the quality of one’s life in work and home spheres is key to achieving a balance. However, given that WLB connotes different meanings to different people (McMillan, Morris, & Atchley, 2011), it is essential to understand individual contexts in the WLB discourse.

Among the limited number of theories available to guide WLB research, five appear to be popular: human ecology theory, spillover theory, compensation theory, role balance theory, and work-family border theory. The human ecology theory provides a systematic approach to studying families. It highlights the relationships between families and economic environment with an emphasis on the interactions with people’s earning and caring (Duncan & Pettigrew, 2012). The spillover theory (Ducan & Pettigrew, 2012) posited that an individual’s emotion and behavior in one sphere can affect his or her emotion and behavior in the other sphere, positively or negatively. According to the compensation theory, people engage in activities in one sphere that satisfy their needs regarding what they are missing in another sphere (Clark, 2000). From the role balance theoretical perspective, “individuals prioritize roles hierarchically for organizing and managing multiple responsibilities” (Grzywacz & Carlson, 2007, p. 456). Prioritizing one’s roles is often influenced by one’s socialization process, and gender may be a critical component in determining the roles (Symoens & Bracke, 2015). All but the human ecology theory focus on examining the extent of individuals’ involvement (e.g., their attitudes, emotions, and efforts) in the two different domains—work and family. However, because spillover and compensation occur simultaneously within individuals, these theories cannot sufficiently explain why people react the way they do.

Attempting to advance work-family theories, Clark (2000) presented the work-family border theory to explain the complicated interactions between the boundaries. Clark’s central argument is that “individuals manage and negotiate their work and family spheres and the borders between them in order to attain balance” (Clark, 2000, p. 750). Here, work and family exist in distinctive domains because each has different rules, thought patterns and behaviors, and different ends and means. Despite the differences, Clark believed that work and family affect each other and people try to integrate these two different areas to some degree. This theory addresses how domain integration and segmentation, border creation and management, border-crosser participation, and relationships between border-crossers and others at work and home (Clark, 2000), result in work-family balance. Therefore, the work-family border theory is useful to explain the dynamics occurring in an individual’s work and family spheres.

Married Women’s Career Lives in Korea

Women’s career development is often recognized as more complex than men’s due to multiple barriers embedded in social, cultural, and political structures. The challenges that women generally have to overcome in their career paths include traditional gender role biases, unequal employment opportunities, and work-life conflicts (Coogan & Chen, 2007). Despite these challenges, married women assume additional responsibilities, which makes them more vulnerable than men and single women in the labor market (Brinton, 2001; Oh et al., 2012). When a woman’s marital status is combined with a conservative and patriarchal culture, it can have a substantial impact on her career.

In Korea, the main sources of married women’s career barriers can be understood from two perspectives—the traditional gender divide in family roles and the unfriendly organizational culture for women (Oh et al., 2012). According to The gender gap index 2017 (World Economic Forum, 2017), the overall rank of gender inequality in Korea was 118 out of 144 countries. Korea was ranked particularly low in the areas of wage inequality (120th) and economic participation and opportunity (121st). These results provide strong evidence of gender inequality in Korea and Korean women’s vulnerability in the job market. Furthermore, the OECD (2016) well-being report for full-time employees revealed the traditional family roles of Korean married couples. In dual-income households, Korean women commonly spent 3.14 hours per day on housework while men invested only 40 minutes (OECD, 2016). This is another manifestation of the traditional gender roles in the current Korean family tradition.

Gender inequality in Korea has a strong imprint of Confucianism, a school of philosophy that has been a foundation of Koreans’ value systems and social structures for the past thousand years (Kee, 2008). In the Confucian teaching that stresses an individual’s faithful role performance according to his or her identity and social class, women are expected to obey and respect their men’s (fathers and husbands) authority and perform family roles as a mother, a wife, and a daughter-in-law, while men assume the breadwinner role as the head of the household. Although the traditional gender role expectation extends beyond the Korean context, it is prominent in Korea given the profound influence of Confucian values. In consequence, the long-lasting prejudice and gender-based practices prevail at work and home even today (Lee & Lee, 2014). Under this strong Confucian influence, assuming a mother’s role has become a primary reason that Korean females voluntarily opt out of the workplace. Additionally, Korea is known as a country gripped by the education fever of parents who want to send their children to elite Korean universities. Because children’s education is largely regarded as the mothers’ responsibility, Korean working mothers who have difficulty in providing their full support for their children’s education are likely to suffer from a sense of guilt, which becomes another cause of women’s career interruption (Ministry of Gender Equality & Family, 2014).

Next, the traditional organizational culture in Korea that has given rise to such male-centered practices as socializing after work, frequent overtime work, and long working hours is another major hurdle for married female employees. Particularly, the tradition of working long hours is frequently cited as a big roadblock to women’s economic participation. Research shows that Korea is one of the overworked countries, with the second longest working hours among the OECD nations; that Korean employees work for an average of 44.6 hours per week, compared to 32.8 hours in other OECD countries (OECD, 2012). In addition to working overtime during weekdays, full-time employees in Korea commonly work over the weekends, adding additional 16 work hours to the already long hours and making Korean employees’ actual working hours much greater than 44.6 hours (The Korea Herald, 2018). As a result, many Korean employees struggle with their WLB, which is evidenced by the fact that Korea ranked the 36th out of 38 countries in the WLB indicator of OECD better life index (OECD, 2016). For married female employees, long working hours are disadvantageous because they generally have more family responsibilities than their male counterparts or non-married females (Hong, 2012). In sum, the challenges Korean women encounter in their career path are deeply rooted in the traditional values at both national and organizational levels.

Theoretical Frameworks

Through our literature review, we found that two theoretical perspectives are helpful in explaining the dynamics of HEMFE’s WLB, especially in terms of the attitudes they take toward their career and the way they manage their WLB. These two theoretical perspectives are the kaleidoscope career model and conservation of resource theory.

Kaleidoscope career model. Proposed by Mainiero and Sullivan (2005), this theory posits that women’s career paths are shifted over time by their needs, interests, and life circumstances between the interaction of work and life domains (Cabrera, 2008). While the scholars described the phenomenon of the talent drain of high-achieving women, especially working mothers, as the opt-out revolution, they also identified gender differences in career patterns. Mainiero and Sullivan (2005) likened women’s career paths to a kaleidoscope with the following statement:

Like a kaleidoscope that produces changing patterns when the tube is rotated and its glass chips fall into new arrangements, women shift the pattern of their careers by rotating different aspects of their lives to arrange roles and relationships in new ways. (p. 111)

Given that women are sensitive to the needs of their family and accordingly integrate them into their careers, this theory provides an interpretation that women’s career patterns are relational and situational (Mainiero & Sullivan, 2005).

The kaleidoscope career model (KCM) consists of three parameters: authenticity, balance, and challenges, which are revealed at different stages of one’s career. The first parameter, authenticity, is connected to the interplay between women’s personal development and work-family issues. Authenticity addresses the following question: “Can I be myself in the midst of all of this and still be authentic?” (Sullivan & Mainiero, 2008, p. 35). This parameter is salient in the late career stage. The second parameter, balance, is a predominant issue in mid-career. It concerns women’s career decisions about how well they can balance work and non-work issues so that they can create a balanced state. The third parameter, challenge, is related to goal achievement. It is a phenomenon that women more likely to experience at their early career stage (Mainiero & Sullivan, 2005; Sullivan & Mainiero, 2008). The KCM helped us capture the HEMFE’s career values and attitudes and understand why many of them have embraced different career values in the process of WLB. This model also enabled us to appreciate the changing nature of work-life priorities for women.

Conservation of resource theory (COR). This theory delineates the relationship between an individual’s resource loss or acquisition and his or her work-life balance. The basic principle of the COR theory is that people tend to protect their current resources and obtain new resources they value (Hobfoll, 1989). The resources take a variety of physical and psychological forms, such as financial assets, personal characteristics, feelings, knowledge, relationship, health, childcare support, and stable employment (Hobfoll, 2001). Although this theory has been commonly used to guide motivation research (Halbesleben, Neveu, Paustian-Underdahl, & Westman, 2014), it helps illuminate triggers for an individual’s distress caused by the role conflicts occurring in work and family domains.

From the COR theory, marital status or parenthood may be required for an individual to acquire resources essential to perform specific roles such as a parent or a spouse. When assuming different roles, individuals likely experience stress, especially when they have limited or no resources due to lack of energy, time, or incompatible behaviors (Grandey & Cropanzano, 1999). Hobfoll (2001) noted that stress usually occurs under two conditions: (a) when the value of the resource loss is greater than the value of resource acquired; or (b) when an investment of resources falls short of one’s expectations, which easily leads to work-life imbalance. The COR theory provides a theoretical guideline for examining the dynamics between resource loss and resource acquisition, as well as the impact of one’s resource management on one’s WLB.

Methods

We adopted the descriptive or transcendental phenomenological research design to explore HEMFEs’ lived experiences with WLB. By adopting descriptive instead of hermeneutic (interpretive) phenomenology, we focused on describing participants’ experiences, rather than presenting the researchers’ interpretations (Moustakas, 1994). The original meaning of transcendental is “everything is perceived freshly, as if for the first time” (Moustakas, 1994, p. 34). In line with this concept, we adopted Husserl’s idea, epoche (suspending the researchers’ judgement toward the participants’ experiences) in order to capture the HEMFEs’ perspective on their WLB experiences. The phenomenological design calls for a textual description of the individuals’ significant experiences and a structural description of specific contexts. This approach helps unfold the essence of lived experiences with more structured procedures (Moustakas, 1994).

Sampling

To select study participants, we used a combination of criterion-based, maximum variation, and snowball sampling methods (Patton, 2002). The criteria we used include: (a) being married; (b) having received higher education (bachelor’s degree and above); and (c) being currently employed in Korea. To collect information-rich data (Patton, 2002), we adopted the maximum variation sampling technique to recruit women with diverse backgrounds (e.g., different organizational types, family types, and the number of children). The participants were recruited through the first author’s personal networks in Korea and referrals from participants (i.e., snowball sampling).

The participants. A total of 16 women participated in our study and we gave each a pseudonym to protect her identity. As Table 1 shows, all the participants have been married for an average of 8.9 years. Eight of them received a bachelor’s degree, six had a master’s degree, and two had a doctoral degree. The participants averaged 37.3 years old. All of them were mothers with one child (8) or two children (7), except for one who had no children at the time of the study. The age range of their children was from 2 to 11, with the average being 5.3 years. At the time of interviews, the participants were working in diverse types of organizations in Korea, including private (9), public (3), and foreign companies (4). All of them were full-time employees, with 14 in mid-level positions.

Data Collection

We collected data from two sources: interviews and observations. Using a pre-developed interview guide with semi-structured, open-ended questions, the first author conducted individual, face-to-face, in-depth phenomenological interviews at the location and time selected by each participant. All the interviews were audio recorded with participants’ prior consent. Each interview lasted between 50 and 123 minutes. All the interviews were conducted in Korean and transcribed verbatim in Korean; only data cited as direct quotes were translated into English. Each transcript was shared with the participants to verify accuracy. During the interviews, the first author also made observations about the participants and took extensive notes. The observational data helped us later create rich descriptions of each participant and contextualize their experiences (Merriam, 2009). To ensure the trust-worthiness of our findings, we employed multiple techniques including data triangulation, member checking, and research journaling.

Data Analysis

We followed Creswell’s (2007) six steps to analyze interview and observational data: (a) data managing, (b) reading and memoing, reading through texts and forming initial codes, (c) describing, (d) classifying, (e) interpreting, and (f) representing and visualizing. The first three steps were related to creating the phenomenology database at the initial stages of analysis before performing the actual analysis. The third step, describing, required us to describe and bracket out our own experiences with WLB and assumptions about the participants’ experience (epoche, Creswell, 2007). In the fourth step, we focused on identifying significant statements from the data to bring important meanings about the phenomenon. During the analysis, we gave equal value to all the data (the method of horizontalization). Then, we grouped the data into larger units of information. Next, we developed a rich description about what each participant’s WLB experience was (textual) as well as how it occurred (structural). Through this process, we were able to identify the essence of individual and shared experiences. In the last stage, we reported the essence of the identified experiences in rich narratives. To ensure accurate interpretation, we shared our findings with the participants and incorporated their feedback into the final report.

Findings

Women’s Experiences with Work-Life Balance

From multiple rounds of data analysis, we identified six superordinate themes and thirteen subthemes (Table 2). They are: (1) the meaning of work-life balance; (2) support systems; (3) career aspiration: thin and long; (4) concerns; (5) WLB strategies; and (6) hope: expectations for the future.

The Meaning of Work-Life Balance

When asked to define WLB, the participants shared the same understanding in that they identified life with family or the home domain, but their perceptions on balance were noticeably different in four ways. They are: (a) a state of compatibility without role conflicts, (b) high psychological satisfaction with less psychological distress, (c) an individual’s appropriate time distribution, and (d) a process of negotiation based on contingency.

First, more than half of the participants stated that WLB is a state of compatibility in which a person performs the assigned roles properly without experiencing any role conflicts between work and family. Although the study participants shared different understandings of WLB, they all perceived balance as compatibility between work and family.

Second, some participants viewed WLB as the matter of one’s psychological satisfaction and having less psychological distress in both work and family. Lami shared, “the balance is that I feel satisfied with both spheres, respectively. In explaining one’s work-life balance, it’s important to have a sense of satisfaction at work and home.”

Third, for some participants, WLB was associated with their faithful role performances based on appropriate time distribution. They highlighted their proper time distribution by viewing balance as the condition in which they can have the autonomy to take control over their time.

When I can plan and utilize the given finite time properly, I believe it’s a balance. If I can fully anticipate my work schedule every day and plan my tasks at work and home based on the schedule, I can establish the boundaries to some extent […] For me, to be able to perform multiple roles at work and at home is the balance. (Gyungock)

Lastly, to some participants, WLB was a process of negotiation based on contingency. Minjung said,

I don’t think that the balance is that an individual is equally involved with her work and family and gains the same results from there […] in my current condition, I try to achieve a balance by negotiating my realities. For example, these days, I just do the minimal domestic work and rely on dining out while focusing on my jobs. If not, all my balance I’m maintaining now might be broken. This is my own balance, currently.

Support Systems

Our sixteen participants had some support systems in place to balance their work and life. All of them had at least one leading support system on which they partially or totally relied. Three sources of support were identified: family, colleagues, and babysitters.

Family. According to the study participant, the most significant support they received came from their families, including their mothers, mothers-in-law, and husbands. Twelve of the sixteen women (75%) had their mothers’ or mothers-in-law’s help with child care. For six participants, their mothers or mothers-in-law took full responsibility as the primary caregivers for their grandchildren since they were born. In these cases, the grandmas fulfilled many of mothers’ duties, such as sending their grandchildren to the daycare centers or schools, picking them up after school, preparing their meals, bathing them, and putting them to bed. To extend their full support, the participants’ mothers or mothers-in-law brought their grandchildren to their home and directly raised them, or they took care of their grandchildren by living in their daughters’ home during the weekdays.

My mom told me, “I will take care of your son. So, I want you to continue to work as much as you can.” From my son’s birth to date, my mom has looked after my son. He grew up at my mom’s home until he was 4 years old. After he became a kindergartener, my mom stayed at my home to take care of my son during the weekdays and goes back to her home during the weekend. Thanks to her full support, I could focus on my job and have gotten promoted fast. (Fangsook)

In some cases, due to the childcare, the parents or parents-in-law voluntarily moved to live near their daughters, or the participants opted to move to be close to their parents’ residences. For most of the participants, their mothers and mothers-in law were the best replacement for them as the primary child caregiver because they could be completely trusted. In two cases (Ayoung and Bokyung), the husbands played an equal parenting role in childcare, which was rare in the Korean context, while most of their husbands did not actively participate in domestic work and parenting roles.

My husband is the strongest support for my career. He almost raised my son by himself during my postdoctoral period in the U.S. My role as a traditional mom was not big. (Ayoung)

Colleagues. Some of the participants pointed out that having a good relationship with their colleagues contributed to a smoother work and family life. Nami said,

We consisted of global team members. My boss worked in England. As we couldn’t meet in person often, I tried to be more communicative with him. When I had personal difficulties, I frankly shared them with him. I also tried to remember my boss’s personal events and care about them. We built a good relationship, and I gained my boss’s trust. Thanks to the good relationship, after my baby’s birth, I was given an opportunity for telecommuting during my childcare. (Nami)

Live-in babysitter. Pado was the only participant who had hired a live-in babysitter. Being a senior manager at a foreign company and having a husband who is an ophthalmologist, Pado had the financial capacity to hire a live-in babysitter for a long time. Pado’s career has been supported by the live-in babysitter from her first son’s birth to the present. She relied on her babysitter for all the domestic tasks (e.g., cooking, cleaning, laundering, and childcare) except for the education of her children. Pado shared,

I have few tasks as a mother and a wife at home. My babysitter takes care of almost all the domestic chores. I don’t do housework very much. Instead, my major role at home is my children’s education. I read with my first son, who is a first grader at an elementary school, because he can’t study by himself yet.

Career Aspirations: Thin and Long

All the participants were very eager to work. Nevertheless, the majority of them did not have a strong desire for career advancement, primarily because of their family-related concerns or responsibilities, especially in the area of childcare. Borrowing Gyungock’s words, most of the participants’ attitudes toward their careers can be characterized as thin and long, which means pursuing low- or mid-level positions with less responsibility so that they could easily and consistently perform dual roles at work and at home.

Strong craving for career continuity. All the sixteen participants expressed their strong desire for a continuous career for several reasons: (a) financial support, (b) being a role model for their children, and (c) self-fulfillment. The biggest reason shared by half of the women was the economic benefit of their jobs. They had a realistic view about their work—providing financial support for their family. Although some participants felt a sense of guilt, that is, they could not fully take care of their children, they believed their economic contribution would enhance the quality of their family’s life. Another reason was to serve as a role model for their children. Eunyoung kept sharing that the strongest motivation for her to stay in her current job was her daughter. She wanted her daughter “to recognize and respect me as a professional career woman, not treating me as just a mother.” Finally, participants also identified self-fulfillment as a motive for keeping their jobs. Fangsook reinforced, “As long as I am satisfied with my job and careers, I won’t abandon my job.”

Lack of desire for career advancement. Although all the participants spoke of a strong desire to continue to work, ironically, half of them expressed little interest in career advancement. Interestingly, we noticed that the women who had low career ambition were also the primary caregivers who received little childcare support. Although they felt sorry about their lack of devotion to work, compared to the period when they were single or before having children, the added roles as a mother had prompted these women to put childcare first. Consequently, it was difficult for them to spend more time on work or to participate in company events as they used to. These women also recognized that their choice might have a negative impact on their career advancement; therefore, they did not set high expectations for themselves. Chaeock acknowledged,

Currently, I don’t think I am pursuing a great vision for my job. While raising my kid, I’ve been stressed and argued a lot with my husband. As I felt much pressured by the role of mother as the primary caregiver, I couldn’t help reducing my career aspirations […] gradually.

Concerns

As all participants were performing multiple roles simultaneously, they felt that their commitment to either work or family, or both, were limited. Hence they had mixed feelings about work and family. Four major concerns were shared by the participants: childcare stress, burnout, personal life, and feeling out of the loop at work.

The most prominent concern was about childcare stress, which was mostly linked to the feeling of guilt toward their children. As almost all the participants recognized themselves as primary caregivers, they felt even more guilty when comparing themselves to stay-at-home moms. The younger their children, the more stressed the women felt. This feeling, combined with the conservative Korean culture, contributed to the women’s psychological distress.

Many participants also experienced a state of emotional and physical exhaustion caused by prolonged distress and pressure associated with their multiple roles. Particularly, those who had to take care of their child or children alone complained about their physical exhaustion more than the other women who received childcare support.

For some participants, a desire to have a personal life was a big issue. Since they usually had to take care of their children after work at the expense of time for rest, it was challenging to have personal time. In order to find their lost life due to their full devotion to childcare, the participants expressed their desire to have a personal life for different reasons such as professional development, self-development, leisure activities, social activities, taking a trip, or just taking a rest at home. Chaeock shared, “If my son grows up a little bit more, my burden for childcare will be reduced. I’d like to find another part to my life, something for enjoying life—trips, sports, or anything else I can enjoy.”

The last concern was feeling out of the loop. Some participants felt left out at work because they usually had to leave the office on time for childcare. This means missing opportunity to socialize with their colleagues, build camaraderie, or join company dinners, which is very important in the Korean organizational culture. Frequent absence at company dinners and the inability to work overtime at night likely had a negative impact on the participants’ performance as perceived by their peers. However, knowing that they made a conscious choice for childcare, the women felt that they “should tolerate the consequence of my choice.”

Work-Life Balance Strategies

While all study participants were juggling multiple roles, they seem to have managed to balance work and life in their own way. Four strategies were mentioned most frequently: (a) be present in their roles, (b) lower expectations, (c) positive attitude, and (d) one child strategy.

Be present in their roles. This was one of the most commonly used strategies by the participants to fulfill their assigned roles and duties faithfully at work and at home. Three subthemes identified in this strategy include: (a) reducing the role of spouse, (b) concentrating only on work, and (c) image making as a working mother.

Reducing the role of spouse. When asked about the role of a spouse, all the participants described traditional gender roles, meaning “when my husband comes home, I serve delicious food and make a cozy atmosphere so that he can take a rest.” However, all the participants, except Lami, confessed that they seldom performed the traditional role as a wife; instead, they just concentrated on the role of mother. Lami, being the only participant without a child, was faithful to her traditional wife’s role, spending her time at home doing all domestic chores. In this study, the fifteen working mothers prioritized their multiple roles and put being a mother and employee before being a wife. This is because they believed the importance of spending time with their children during their early childhood. As primary caregivers who knew that their husbands play a minimal role in parenting, the participants needed to save their energy and time by reducing at least one role; in their mind, the spousal role was less important than the parent role.

Concentrating only on work. Some participants said that when they were at work, they were fully engaged. Since they were under pressure to leave on time or earlier than other colleagues because of childcare, they concentrated on their work without taking any down time.

I just focus on completing my job at work. I don’t usually hang out or chat with my colleagues. Except for going to the restroom, I pay undivided attention to my work so that I can finish it on time. Approaching the closing time, I hurry to leave the office to be with my children. (Gyungock)

Image making as a working mother. Some women intentionally built an image of a working mother to avoid working overtime, taking extra work, or attending company events. These women found some ways of coping with their changed condition at work. For example, while emphasizing their identity as a mother responsible for childcare, the participants tried not to leave the office very late. Gyungock wisely used the image of a working mother by switching her dual identities as a mother and an employee in each domain. She said,

I’ve established my image as a working mom. Even though I’m not overtly saying like “since I am a mother with two young children I should leave on time to look after them,” I let my colleagues feel like that. So, my colleagues don’t entrust urgent work to me. Reversely, at home, I try to engrave the image of a working mom in my husband’s heart. This is my strategy to build my identities at work and family.

Set lower expectations. Regarding some tasks at home, many participants set lower expectations for their husbands and themselves. In this study, 14 of the 16 women did not have high expectations from their husbands. Although they had complaints about their husbands’ minimal participation in parenting and domestic work, ironically, they believed lowering their expectations from their husbands would reduce their psychological stress. All the women reported that they fought a lot with their husbands as newlyweds in the hope that they could eliminate their husbands’ prejudices against married women. But as time went by, they gradually abandoned their expectations because they realized it was too time- and energy-consuming and meaningless to lecture their husbands who “have no ideas about sharing equally domestic work and parenting roles.” Considering our participants’ average length of marriage was 8.9 years, they believed the life pattern as a married couple was already set by then. The following direct quotes are representative.

I don’t have big complaints about my husband now because I think I’ve been habituated to his patterns [frequent overtime and few domestic and parenting roles] for seven years since I got married. (Kyunghee)

I almost abandoned my expectation about my husband. During the weekend, he usually takes a nap all day long and doesn’t listen to our baby’s crying at all. I just leave him alone. While I accept him the way he is, I try to enjoy my roles with a positive mind. (Ooju)

Another reason for the participants’ low expectations was closely linked to the organizational culture in Korea, characterized by collectivism, frequent overtime work into night, and company dinners. Some participants thought their husbands were very domestic but the work environment made them not so. That is, the Korean organizational culture often prevents their husbands from being involved with domestic work.

For some participants, another strategy was to lower expectations on their traditional role of homemaker. They tried to have minimal involvement in domestic work by reducing the amount of time they spend on cooking or cleaning. Although they felt the pressure of cooking and providing healthy food as homemakers, they chose to save their energy and time for childcare by relying on takeout food services or dining out.

Positive attitude. Many participants tried to embrace a positive attitude in everyday life in order to manage their psychological distress. Their attitude was based on the following motto: “If you can’t avoid it, enjoy it.” Accepting that they cannot avoid multiple responsibilities, the participants tried to find the positive aspects in their current situation.

One-child strategy. Among the fifteen participants with children, eight women (53.3%) had only one child. They had no desire to expand their family because they were not confident about performing the added responsibilities resulting from having more children. Additionally, considering their husbands’ low participation in domestic work and childcare, the participants believed that the additional work caused by having more children would have a negative impact on their WLB. Fangsook stated,

I don’t force my husband to do any domestic work or childcare. I just take care of everything by myself at home. Naturally, I gave up having a second child, which means my capacity in which I can bear my situations and don’t have a feeling of dissatisfaction with the current condition […] Honestly, I want to have one more child, but I cannot help but have just one to maintain my work-life balance.

Hope for a Better Future

Half of the participants were optimistic that married women’s quality of life would be better in the future. Particularly, they took a positive outlook in three areas: (a) national policies, (b) organizational culture, and (c) parenting of the younger generation. The national policies and organizational culture were closely related. Many women felt that their organizational climate has slowly become family-friendly, compared to the time when they first entered the workforce. They believed that the national policies such as paid maternity leave and childcare leave (both of which have been guaranteed under the law), Equal Employment Opportunity and Work-Family Balance Assistance Act (since the mid-2000s), had driven organizational culture change. Also, some participants noted that the increase of female employees contributed to creating a more woman-friendly work environment where frequent company dinners and business drinking may no longer be the business norm.

Lastly, as discussed earlier, almost all participants had complained about their husbands’ lack of participation in parenting and domestic work. However, Dajung and Lami, in their 40s, felt positive about younger generation’s parenting. Having witnessed their male juniors’ different parenting style, these women believed that new generation fathers would be more involved as parents than those in their generation. Dajung said,

Since my husband is a traditional Korean man, he rarely does domestic work or childcare. However, while talking with some male juniors in my company, I feel the generation gap between my husband and them even though their ages are just around ten years apart. For example, the juniors start work one or two hours late after taking their kids to the hospital when their children are sick. When I am in the same situation, I am always the one who takes my kids to the hospital. I can’t imagine the opposite case. While watching them, I feel the generations are gradually changing.

Discussion

The findings from this study revealed how the highly educated and married Korean female employees had perceived and described their WLB experiences. Their experiences illuminate five points that are worth further discussion.

First, WLB is a highly individualistic and contextualized experience. The women in this study had their own interpretation of WLB based on their needs within their contexts. For example, Dajung and Eunyoung, who had difficulty separating work and family, highlighted the importance of establishing clear boundaries in defining balance. Lami, who placed a high value on her personal happiness, focused on seeking individual’s psychological satisfaction in both domains. The subjectivity in defining WLB was consistent with Fleetwood’s (2007) observation that WLB has different meanings to different individuals. This finding was also aligned with Clark’s (2000) view that the balance between work and life is a process of negotiating in the borders with given realities.

Second, the balanced state of work and life lies in maintaining dual identities as a mother and an employee. Despite the different understandings of WLB, all our study participants believed that they had managed to achieve work-life balance because they had not yet experienced career interruptions. In other words, these women considered work-life balance as the state of maintaining their jobs while fulfilling their family duties. When asked about their satisfaction with WLB, the majority of the participants expressed a high level of satisfaction because they were able to continue to work and their children were well taken care of by reliable caregivers (themselves, their mothers or mothers-in-law, or a live-in babysitter). For highly educated women, the meaning of a job is deeply rooted in their value for independent identity (Jang & Merriam, 2004). Since losing jobs meant losing identity as an independent individual, the women stressed their career continuity as an indispensable component of WLB. In order to create a balancing state, “being me and being the mother of my children,” the women use compromising as a strategy (e.g., expecting less from their husbands, reducing their desire for career advancement, limiting networking opportunities with colleagues, and opting to have only one child). This finding is consistent with Supple’s (2007) and Bailey’s (2011) research that revealed the high value for three identities—self, work, and motherhood—placed by full-time working mothers in the U.S. In this sense, we may safely conclude that that regardless of the context, Western or non-Western, working mothers have to manage the tension between being a mother and being an employee. This makes identity a key issue to consider when it comes to understanding WLB.

Third, women’s career aspirations were shaped by the way they defined the meaning of career in their individual context. As mentioned earlier, all participants expressed a strong craving for continuing employment; however, half of them had little interest in career advancement. Connecting the previous discussion, those with low career ambitions, instead of feeling dissatisfied, felt lucky to have been able to maintain a career while taking care of their children. They stated that after becoming a mother, the concept of career success was changed into “catching two rabbits [work and family] at the same time.” This perception is aligned with Cho et al.’s (2015) finding about Korean women leaders who defined success as balance between work and family. The changing career attitude shared by our participants is also aligned with the idea behind the kaleidoscope career, that is, those who are in their mid-career focus on the balance first and would adjust their career ambitions to achieve the work-life balance (Mainiero & Sullivan, 2005). However, it is worth noting that the women participants who received full support for childcare demonstrated a higher desire for career achievement and promotions. This finding has a significant policy implication for organizations in Korea.

Fourth, WLB is deeply connected with how to effectively manage one’s current or potential conflicts at work and home based on finite resources. In this study, two resources, time and energy, were recognized as sources of conflicts. Being the primary caregivers and full-time employees at the same time demand significant amounts of time and energy from our study participants, thus causing conflicts. This role conflict due to a scarcity of resources can be understood from the COR theory; it is also consistent with McMillan, Morris, and Atchely’s (2011) argument that “the total amount of time and/or energy available to an individual is fixed and participation in multiple roles decreases the total amount of time and/or energy available to meet all demands” (p. 9). Along this line of thinking, it would not be difficult to understand why one of the participants’ WLB strategies was reducing the time and energy-based conflicts. In this study, the women attempted to create balance in their world by intentionally or unconsciously reducing the time and/or energy allocated to different roles, depending on their priorities and the degree of urgency.

Among various WLB strategies, building support systems was the most frequently cited by the participants. However, our findings also revealed different levels of support provided by different family members—mothers or mothers-in-law as the biggest support and husbands as the least support. This reflects a unique cultural phenomenon prevailing in many Eastern countries, including Korea. Additionally, as our study shows, the level of resource possession or acquisition influenced women’s WLB experiences, especially in terms of childcare stress, domestic work, and career aspirations. If the women experienced more resource loss (e.g., burnout, feeling out of the loop, and childcare stress) than resource acquisition (e.g., organizational support, family support, WLB strategies, and positive attitude), they would likely experience work-life imbalance. This finding suggests that work-life imbalance occurs when there is a tension between resource loss and resource acquisition.

Lastly, an individual’s WLB is not a fixed state but is constantly evolving. This is because WLB is contingent upon the values individuals place for different roles. In other words, the roles expected of an individual likely differ at different life stages; so are the emphasis placed by individuals on their life roles (Super, 1980). For example, almost all our participants gave their current role of mother the top priority because their children were still very young. However, for some participants who had passed the critical early parenting stage, their focus gradually shifted from their children to their own personal lives. This change of focus was made clear by our participants:

After my kids became elementary school students, the two values [focused on work and my child] to balance my work and life were changed. My current interest in work-life balance is the balance between the sum of work and my child and my personal life. (Chaeock)

This finding shed light on the evolving nature of WLB according to one’s different life course stages.

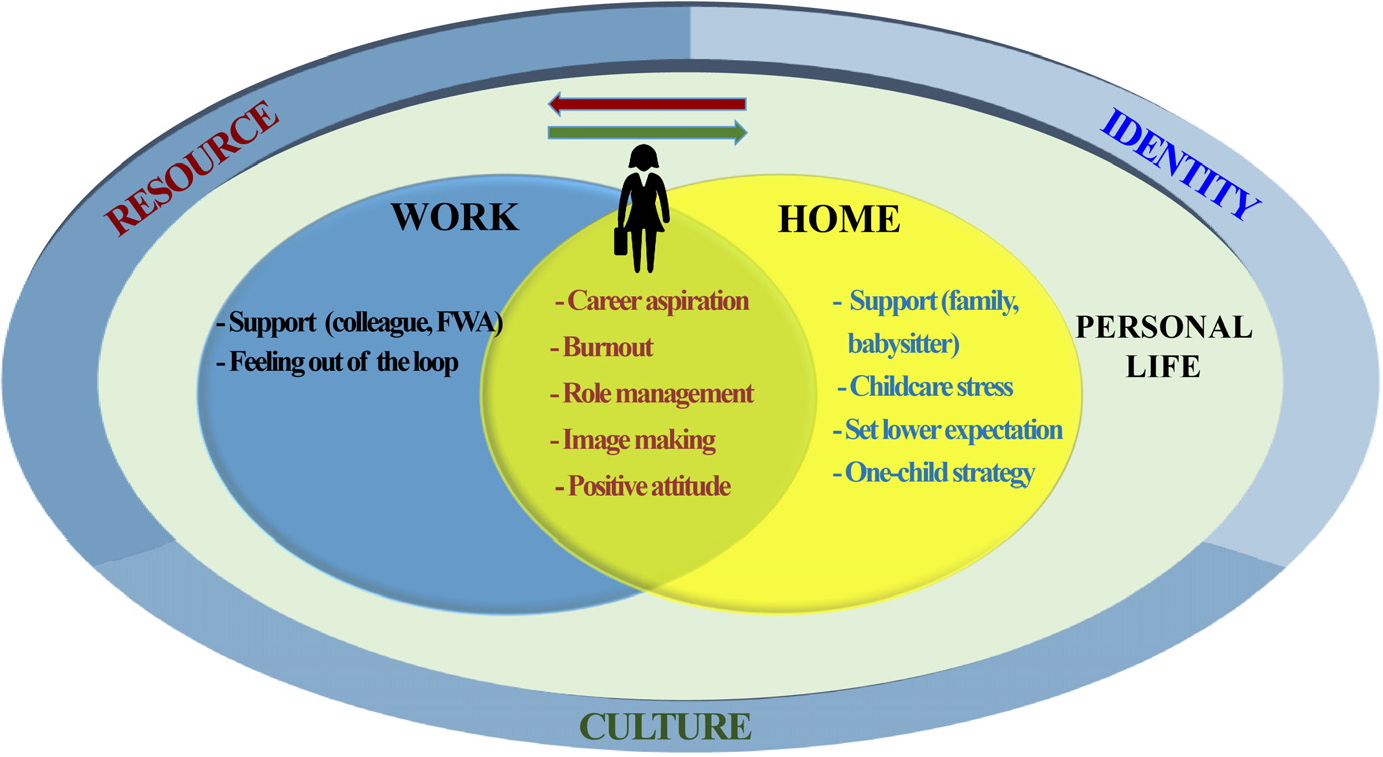

Figure 1 presents a new conceptual framework derived from this study. As it illustrates, the women’s WLB experiences were shaped by the interaction among three components—resource, identity, and culture. In summary, given the finite time and energy resources available, how to acquire and utilize different resources is key to create WLB. In addition, the status of WLB is significantly influenced by the level of resources possessed. From the identity perspective, there exists the tension between being a mother and being an employee. Finally, WLB experiences are highly individualized, subject to family circumstances, organizational culture, and national culture.

Practical Implications

This study is one of few empirical studies focusing on highly educated and married female employees’ experiences with WLB in a non-Western context. The findings provide valuable insights and guidelines for national policy makers, organizational leaders, and female employees.

At the individual level, a clear understanding of the WLB context is the first step. Given the highly subjective nature of WLB, critical self-reflection can be a useful tool to gain deeper insights into one’s family (e.g., number of children and family support) and job/organization (e.g., the level of work demands, the provision of family-friendly policies), and resources available or needed). Based on the outcomes of the personal reflection, a working mother needs to communicate candidly with all the relevant parties (e.g., families, supervisors, and colleagues) about her specific needs for WLB. While critical reflection does not directly lead to work-life balance, it can raise the awareness of multiple parties and deepen their understanding of WLB related issues.

At the organizational level, the roles of an organization in promoting the quality of employees’ lives is well recognized (Burke, 2011). In this study, a critical factor affecting Korean married female employees’ WLB outcome is the traditional organizational culture that promotes long working hours, collectivism, and a male-centered structure. Many participants hoped for an organizational culture change with a special emphasis on the reduction of long working hours so that employees can leave work on time for better WLB. We encourage organizations to seek a variety of family-friendly policies and practices such as flexible workplace arrangements. However, as the execution of the new practices may involve pain and costs for several parties such as employers and employees, it is important to identify common interests and create a shared vision among all the involved stakeholders.

Lastly, an interesting finding in the study was that the majority of our participants received little or no spousal support, making their WLB challenging. The Korean government can play an important role in supporting married female employees’ WLB. Specifically, the central government can design women and family friendly national policies and programs that evoke fundamental change in the existing traditional culture. Without the buy-in from all the stakeholders, the government is unlikely to achieve satisfactory results. The first action that may be taken by the government is to articulate how each stakeholder may benefit from the new policies and programs. We encourage the government to consider various strategies regarding how to gain buy-in from multiple stakeholders. Examples of strategies may include making recommendations of FWA programs to organizations, and providing financial support to family-friendly organizations and recognize women-friendly practices adopted by organizations.

Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

In this study, we focused exclusively on married female employees because the WLB issue in Korea has been traditionally framed as the problem for female employees, especially working mothers. We encourage future studies to include other groups of populations to expand the perspective of WLB. For example, the sample of this study is primarily married women with children. We call for studies on more married women without children to provide a comparative perspective. Further, one of our findings is that the meaning of balance is influenced by an individual’s context. Considering the subjective meaning of balance, there is a need for future research focusing on exploring married career Korean men’s experiences with WLB. The comparison between both genders’ WLB experiences and meanings of balance is likely to generate fresh insights into WLB.

Secondly, all the participants in this study happened to be in their 30s and 40s by default, not by design. This presents an opportunity to look at female employees in other age ranges. This is because an individual’s life/career stage would influence her WLB experiences. Additionally, considering the young ages of our participants’ children (averaged 5.3 years old), there is also a need to study female employees with older children (e.g., teens and adults). Further, our participants were a relatively privileged group in terms of their education level (higher education), employment status (full time), and social-economic status (the middle-class). Future research may focus on married female employees with other social, economic, educational, and family backgrounds (e.g., part-time or hourly employees, low wage workers, and single workers).

Thirdly, an individual’s life is composed of multiple dimensions, such as work, family, personal, community, and spirituality (Whittingtone, Maellaro, & Galpin, 2011). This study focused only on two domains (work and family). Further research may consider other domains and their individual or collective impact on WLB. Doing so will help generate a multi-dimensional view of WLB.

Finally, this study focused on one country context. As the individuals’ experiences with WLB are likely different in different national contexts, cross-country comparisons would be meaningful for future research.

Acknowledgments

* This article was partially modified and extracted from the author’s doctoral dissertation.

References

- Bailey, K. J., (2011), Women in student affairs: Navigating the roles of mother and administrator, (Doctoral dissertation), Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database (UMI No. 3500089).

- Brinton, M. C., (2001), Married women’s labor in East Asian economies, (Ed.) Women’s working lives in East Asia, p1-37, Stanford, Stanford University Press.

- Burke, W., (2011), Organization change: Theory and practice, (3rd ed.), Thousand Oak, CA, SAGE.

- Cabrera, E., (2008), Protean organizations: Reshaping work and careers to retain female talent, Career Development International, 14, p186-201.

- Cha, J. Y., (2015, March, 19), Females who enter colleges are 75%, males are 68%..., Yonhapnews, Retrieved June 7, 2016, from http://www.yonhapnews.co.kr/bulletin/2015/03/19/0200000000AKR20150319086051002.HTML (In Korean).

-

Chang, A., McDonald, P., & Burton, P., (2010), Methodological choices in work-life balance research 1987 to 2006: A critical review, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21(13), p2381-2413.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2010.516592]

-

Cho, Y., Kim, N., Lee, M. M., Lim, J. H., Han, H., & Park, H. Y., (2015), South Korean women leaders’ struggles for a work and family balance, Human Resource Development International, 18(5), p521-537.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2015.1076562]

-

Clark, S. C., (2000), Work/family border theory: A new theory of work/family balance, Human Relations, 53(6), p747-770.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726700536001]

-

Coogan, P. A., & Chen, C. P., (2007), Career development and counseling for women: Connecting theories to practice, Counseling Psychology Quarterly, 20(2), p191-204.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070701391171]

- Creswell, J. W., (2007), Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches, (2nd ed.), Thousand Oaks, CA, SAGE.

-

Duncan, K., & Pettigrew, R., (2012), The effect of work arrangements on perception of work-family balance, Community, Work & Family, 15(4), p403-423.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2012.724832]

-

Fleetwood, S., (2007), Re-thinking work-life balance: Editor’s introduction, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18(3), p351-359.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190601165486]

-

Grandey, A., & Cropanzano, R., (1999), The conservation of resources model applied to work-family conflict and strain, Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54, p350-370.

[https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1998.1666]

-

Greenhaus, J. H., Collins, K. M., & Shaw, J. D., (2003), The relation between work–family balance and quality of life, Journal of Vocational Behavior, 63(3), p510-531.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/s0001-8791(02)00042-8]

-

Grzywacz, J. G., & Carlson, D. S., (2007), Conceptualizing work-family balance: Implications for practice and research, Advances in Development Human Resources, 9, p455-471.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422307305487]

- Halbesleben, J. R., Neveu, J. P., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., & Westman, M., (2014), Getting to the “COR” understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory, Journal of Management, 40(5), p1334-1364.

- Han, H., (2012), Issue of Korean women’s economic participant, KERI Column, Seoul, South Korea, The Korean Economic Research Institute, (In Korean).

-

Hobfoll, S. E., (1989), Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress, American psychologist, 44(3), p513-524.

[https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.44.3.513]

-

Hobfoll, S. E., (2001), The influence of culture, community, and the nested‐self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory, Applied Psychology, 50(3), p337-421.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00062]

- Hong, S. A., (2012), The effects of flexible working on the working parent’s work-life balance: Strategic choice or gender trap?, Family and Culture, 24(4), p135-165.

-

Jang, S. Y., & Merriam, S., (2004), Korean culture and the reentry motivations of university-graduated women, Adult Education Quarterly, 54(4), p273-290.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0741713604266140]

- Kee, T. S., (2008), Influence of Confucianism on Korean corporate culture, Asian Profile, 26(1), p1-15.

- Lee, C., & Lee, J., (2014), South Korean corporate culture and its lessons for building corporate culture in China, The Journal of International Management Studies, 92(2), p33-42.

-

Lee, E., Chang, Y., & Kim, H., (2011), The work-family interface in Korea: Can family life enrich work life?, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(9), p2032-2053.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.573976]

- Lee, S., & Park, Y., (2017), A study on highly educated women’s retirement and career interruption in their 30s, The Review of Eurasian Studies, 14(3), p45-68.

-

Mainiero, L. A., & Sullivan, S. E., (2005), Kaleidoscope careers: An alternate explanation for the “opt-out” revolution, The Academy of Management Executive, 19(1), p106-123.

[https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2005.15841962]

-

McMillan, H., Morris, L., & Atchley, K., (2011), Constructs of the work/life interface: A synthesis of the literature and introduction of the concept of work/life harmony, Human Resource Development Review, 10(1), p6-25.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484310384958]

- Merriam, S., (2009), Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation, San Francisco, Jossey-Bass.

- Ministry of Gender Equality & Family, (2014), Survey on economic activities of career-break women, Seoul, South Korea, Ministry of Gender Equality & Family, (In Korean).

-

Moustakas, C., (1994), Phenomenological research methods, Thousand Oaks, CA, SAGE.

[https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412995658]

- Oh, E., Kim, N., & Uhm, C., (2012), Vocational competency assessment of interrupted women and support measures for their career building, Seoul, South Korea, Korean Women’s Development Institute.

- OECD, (2012), OEDC at a glance 2012: OECD indicator, Retrieved October 30, 2015, from http://www.oecd.org/education/EAG2012%20-%20Country%20note%20-%20Korea.pdf.

- OECD, (2015a), Average annual hours actually worked per workers, Retrieved July 18, 2017, from https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=ANHRS.

- OECD, (2015b), Education at a glance 2015, Retrieved December 12, 2016, from http://www.keepeek.com/Digital-Asset-Management/oecd/education/education-at-a-glance-2015/korea_eag-2015-66-en#page1.

- OECD, (2016), OECD Better life index, Retrieved June 30, 2017, from http://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/topics/work-life-balance/.

- Patton, M. Q., (2002), Qualitative research and evaluation methods, (3ed ed.), Thousand Oaks, CA, SAGE.

- Seo, S. B., (2013, April, 9), Low birth rate, there is no future of Korea: Labor shortages, country ‘shake’, Heraldgyungjae newspaper, Retrieved January 18, 2016, from http://news.heraldcorp.com/view.php?ud=20130409000300&md=20130411004228_AP.

- Statistics Korea, (2016a), Birth rate in Korea, Retrieved June 20, 2017, from http://www.index.go.kr/potal/main/EachDtlPageDetail.do?idx_cd=1428 (In Korean).

- Statistics Korea, (2016b), Aging rate in Korea, Retrieved June 20, 2017, from http://kostat.go.kr/portal/korea/kor_nw/2/1/index.board?bmode=read&aSeq=348565 (In Korean).

-

Sullivan, S. E., & Mainiero, L., (2008), Using the kaleidoscope career model to understand the changing patterns of women’s careers: Designing HRD programs that attract and retain women, Advances in Developing Human Resources, 10(1), p32-49.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422307310110]

-

Super, D. E., (1980), A life-span, life-space approach to career development, Journal of Vocational Behavior, 16(3), p282-298.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(80)90056-1]

- Supple, B. L., (Retrieved), “Life as a gyroscope”: Creating a grounded theory model for full- time working mothers in higher education administration and developing and maintaining a fulfilling balanced life, (Doctoral dissertation), Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database (AAT No. 3283411).

-

Symoens, S., & Bracke, P., (2015), Work-family conflict and mental health in newlywed and recently cohabiting couples: A couple perspective, Health Sociology Review, 24(1), p48-63.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/14461242.2015.1007156]

- The Korea Herald, (2018, February, 28), Shorter working hours, Retrieved March 7, 2018, from http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20180228000911.

- Whittington, J. L., Maellaro, R., & Galpin, T., (2011), Redefining success: The foundation for creating work-life balance, In S. Kaiser, M. J. Ringlstetter, D. R. Eikhof, & M. P. E. Cunha (Eds.), Creating balance?, p65-77, Heidelberg, Berlin, Springer.

- World Economic Forum, (2017), The global gender gap repot 2017, Retrieved March 20, 2018, from https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-gender-gap-report-2017.

- Yonhapnews, (2013, January, 20), S. Korea ranked last in OECD in employment of female college graduates, Retrieved February 20, 2015, from http://english.yonhapnews.co.kr/business/2013/01/20/4/0503000000AEN20130120000800320F.HTML.

Biographical Note: Hyounju Kang is a research professor at the Research Institute for HRD Policy at Korea University, Seoul. Her leading research interests are career development, lifelong education, immigration, gender, diversity, culture, and social justice. She has published several journal articles related to immigrant women’s career development and employees’ work–life balance. She received her doctoral degree in HRD from Texas A&M University, College Station. E-mail: nalgae11@gmail.com

Biographical Note: Jia Wang (Corresponding author) is an associate professor of Human Resource Development in the College of Education and Human Development at Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA. Her research focuses on international and national HRD, crisis management, workplace incivility, and workplace learning. Her research work has been published in a variety of international journals. She currently serves as the Editor-in-Chief of Human Resource Development Review, as well as a member of the editorial boards for three other international journals. She received her Ph.D. in Human Resource and Organizational Development from the University of Georgia, USA and M.B.A. from Aston University, UK. E-mail: jiawang@tamu.edu