Public Sector Education and Gender Inequality: A Mixed-Method Study in Metropolis City of Pakistan

Abstract

Girls' education and participation in economic activities are relatively low in patriarchal Pakistani societies due to stereotypical family roles and cultural and religious inclinations. This study examines the influences of educational institutions and educational actors on gender-role ideologies in mainstream education in the public sector in an urban setting. The study methodology uses a mixed-method research approach; the quantitative analysis is conducted using the Social Roles Questionnaire, and the study aims to explore educators' views on gender roles and their relationship to demographics. Schools' disposition toward gender segregation was investigated through a qualitative Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA). The findings of the quantitative part revealed that the majority of the participants believed in traditional gender roles regardless of differences in their education, parental education, experience, job status, level of teaching, gender, designation, and type of institution (girls only/boys only/co-education). Qualitative analysis showed that educational institutions are playing a significant role in widening the gender gap due to the perceived intention of education being gender-biased that aims at developing boys as income producers and girls as morally rich stereotypical daughters, wives, and mothers. Additionally, education allows girls to shoulder the double burden of work and home in poor and middle-class families with limited cultural and domestic careers; however, for outdoor services, teaching careers are of paramount importance. Furthermore, girls' higher education is considered less meaningful, and participants have a rigid, traditional mindset. This study is unique in that, for the first time, it examines the influence of public-sector institutions and educationists’ personal mindsets on gender-role stereotypes in an urban metropolitan area of Pakistan. This research provides recommendations for policymakers to cater to gender-disparity concerns for the well-being of the nation.

Keywords:

Gender roles, classroom practices, girls’ career, girls’ higher education, PakistanIntroduction

Pakistan is ranked as the third-worst country in the world in terms of gender inequality. According to the World Economic Forum (WEF), its position is 151 out of 153 countries in the gender parity index. In comparison, the slope exhibits a drastic decline from 112 in 2006 to 151 in 2020, far behind Bangladesh and India, which scored 72.6 and 112, respectively (Ahmed, 2019). Gender segregation adversely affects socioeconomic well-being and has a significant relationship with the increased poverty of the nation (Rahman, Chaudhry, & Farooq, 2018).

Researchers have reported that educational institutions play a pivotal role in propagating gender inequality. Oftentimes, educators are bound by conventional ideologies of masculinity and femininity (Gul, Khan, Mughal, Rehman, & Saif, 2012; Pardhan & Pelletier, 2017), which are reflected in classroom practices that are insensitive to gender (Kalra & Sharma, 2019; Sultan, Shah, & Fazal, 2019). Most classroom practices impose hidden oppressions that disadvantage and marginalize girls in different ways (Mahmood & Kausar, 2019). In addition, boys' dominance is evident in co-education classes (Smith, Hardman, & Higgins, 2007) and, no appropriate and prompt actions are taken when boys engage in abusive language and violence against women. In fact, behaviors are normalized by teachers (McCullough, 2017), which leads to an imbalanced environment (Kalra & Sharma, 2019). The patriarchal society of Pakistan adheres to gender-segregating beliefs, such as that men are breadwinners and women are housewives (Rehman & Roomi, 2012) and women are portrayed as passive, dependent, and submissive in textbooks used in educational institutions (Islam & Asadullah, 2018). In addition, men are described as “brave”, “strong”, and “rational”, while women are described as “emotional”, “pretty”, and “sweet” (Mahmood & Kausar, 2019). As part of the instructional design, textbooks, which are considered essential learning tools for students, are aligned with the instructions to impart stereotypical social roles to students (Durrani, 2008). Gender discrimination persists throughout the academic life course (Winslow & Davis, 2016), which results in the systematic transfer of developed ideologies across generations.

While it is commonly assumed that in urban settings, gender discrimination is not prevalent and equal opportunities flourish, Faizi and Butt (2017) and Mehmood, Chong, and Hussein (2018) clearly demonstrate that female education is still restricted despite opportunities available. This study focuses on identifying settled urban educators' beliefs and practices regarding differentiating social gender roles in public-sector institutions. Moreover, this study compares participants' mindsets at the primary and university levels, including junior and senior staff members, to determine whether there is a discrepancy based on their employment status and experience.

Literature Review

Theoretical Framework

Combining feminism with Paulo Freire's critical pedagogy provides a new perspective on gendered teaching-learning processes in an educational context (Mitcho, 2016). This has given rise to critical feminist theory, which is used as the theoretical basis for this research study. Critical feminist theory strives to focus on the hidden forms of oppression imposed on students by educational institutions through which gender inequality is perpetuated (Rosa & Clavero, 2022; Ziv, 2015), which manifests as dehumanization, resistance to social change, and harmful effects on society (Freire, 1970). Feminist scholars have examined how women have historically been considered “the other” in schooling that aims to revive patriarchy through discursive approaches (Durrani, 2008; Sahibzada, Tayyab, & Khan, 2019).

Bell Hooks, an African American social activist, in her book Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center, identified silence as an inability to express oneself, challenge prevailing behaviors, and question the social hierarchical system. She further noted that silence exists everywhere in families, communities, and societies because silence in itself does not imply a lack of speech; rather, it is a subjugating behavior determined by the politics of male hegemony. Silence, she argues, can be overcome if it is not only transformed into speech, but also if speech is heard. The suppressed voice that emerges gives students and teachers the power to challenge the hierarchy (Stamarski & Son Hing, 2015).

Gender Discrimination Through Traditional Societal Practices and Textbooks

Education, being a basic right of pupils, must not be disseminated on the basis of gender, race, language, or religion (Assari & Caldwell, 2018; Muhammad, Haq, & Khan, 2018). Unfortunately, in Pakistan, access to education is highly influenced by gender differences, where females have fewer opportunities to obtain this right (Faizi & Butt, 2017). The disposition toward gender-separated roles narrows down the scope of education for girls (Kapur, 2019; Rotter, 2019). Moreover, women's participation in the labor force is generally lower, and the literacy rate remains more prevalent among men (70%) when compared to women (49%) (Nausheen & Richardson, 2018).

Muhammad et al. (2018) reported that socioeconomic status has a strong influence on gender disparity toward enrolment in the educational sector, and this disparity is higher in low-income households. Moreover, parents assume that taking care of older parents is the responsibility of boys, so their education is preferred (Daraz, Ahmad, & Bilal, 2018) and preferences toward early marriage for girls cause them to stop their studies and engage in domestic life (Salik & Zhiyong, 2014; Zarar, Bukhsh, & Khaskheli, 2017). Tenvir (2015), through her ethnographic study of culturally conservative Pakistani families, observed that girls' education is impeded by male hegemony, which has damaging consequences on girls' lives. Afzal, Butt, Akbar, and Roshi (2013) and Rahman et al. (2018) also endorsed the fact that in the province of Punjab, a male superiority culture is practiced, and gender discrimination is common. In South Asian regions, Islam and Asadullah (2018) examined the quality and quantity of women's under-representation in schools' secondary-level textbooks. Their findings showed that Pakistani course books display the highest percentage of gender stereotypes where women are portrayed with traditional roles such as low-income jobs and passive personalities when compared with Malaysia and Bangladesh. They suggested that these issues need to be addressed for achieving the Sustainable Development Goal SDG-5 “gender equality and empowering women and girls globally” by 2030.

Research Methodology

This research study is designed to identify traditional beliefs regarding gender roles and discrimination in established urban public-sector educational institutions in Pakistan. A mix of surveys and one-on-one phone interviews was used to collect data for this study. The quantitative part was designed to manifest the extent of gender bias among the participants and to generalize the findings. Qualitative methods allowed the researcher to delve deeper into the participants' minds and gain a fuller understanding of the underlying reasons for stereotypical ideologies. CDA manifests itself through qualitative analysis. According to Van Dijk (2006), CDA is guided primarily by the desire to understand pressing social problems. Wodak and Meyer (2009) assert that CDA highlights the requirement for interdisciplinary work to understand how language functions in the constitution and transmission of knowledge in the creation of social institutions. Rogers, Malancharuvil-Berkes, Mosley, Hui, and Joseph (2005) noted that critical theories are most often associated with issues of power and impartiality, and the ways in which economics, race, class, gender, religion, education, and sexual orientation construct and change social systems.

The analysis comprises an analysis of texts, communications, and social practices at the local, institutional, and societal levels. The policies of teaching and learning can be better understood by observing the social problems of the wider community, as well as the language and type of texts used. A Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) was conducted to understand how educational actors’ interactions may affect students’ career paths, individual freedom, and social and cultural forces. In addition, it was conducted to understand what kind of knowledge is emphasized and deemed significant for boys and girls. As suggested by Alkin and McNeil (2001) and Mullet (2018), there was a focus on critical analysis of the above aspects in the spoken language of actors.

The following steps suggested by Mullet (2018, p.7) were employed in this study:

- 1. Select the discourse concerning inequality/injustice.

- 2. Locate and prepare data sources from text/ interview transcripts.

- 3. Investigate the cultural and social context of given data.

- 4. Code texts and identify overarching themes (this can be done through thematic analysis).

- 5. Analysis of external relations/interdiscursivity (i.e., dominant social practices in institutions such as schools).

- 6. Analysis of internal relations (e.g., leading statements, applications of spoken language, context, and speakers' positionality).

- 7. Interpret the data in light of the major themes identified in steps 4, 5, and 6.

After transcribing interviews, the thematic analysis was carried out.

Research Objectives

- 1. Identifying and comparing teachers/administrators’ traditional beliefs of gender roles with respect to their demographics such as pay scale, qualification, level of teaching and experience of teaching, job status, type of school, father’s education, and mother’s education.

- 2. Identify teachers/administrators’ classroom practices toward gender inequality and discrimination in urban public educational institutions. (Determine how teachers’ classroom practices contribute to gender inequality and discrimination among students).

- 3. Investigate teacher’s/administrators attitudes with respect to social change in gender roles.

The quantitative part was designed to meet the requirements of research objective 1, and semi-structured interviews were conducted for research objectives 2 and 3. Research objective 1 examined the significance of the dependent variable with respect to independent factors (pay scale, qualification, level of teaching and experience in teaching, job title, type of school, father's, and mother's education). The p-value was used to determine if the differences prevailed, which was possible using a quantitative method. Research objectives 2 and 3 were subjective in nature and required in-depth analysis. Different participants may hold different views and engage in various modes of discussion with students. The problem could not be resolved quantitatively; therefore, a qualitative interview was considered appropriate.

The interview questions included the following:

- 1. “What is the purpose of education for girls and boys in public-sector schools in urban setting?”;

- 2. “What are your beliefs regarding the importance of higher education for female students at public-sector institutions?”;

- 3. “What social roles should male and female teachers perform?”;

- 4. “In what type of discussions are you involved with your students regarding building their careers?

The purpose of interview question 4 was to find answers to Research objective 2. “In what type of discussions, are you involved with your students regarding building their careers?” intends to ask about teacher-pupils’ engagement in “discussion” that is regarded as indirect yet an essential part of teaching and learning in educational institutions.

In the fieldwork, the researchers interviewed all the participants and transcribed all the interviews using direct literal (secretarial) methods. This was achieved by recording audio calls from 10 participants. These recorded calls were then transferred into a computer compact file, and the material was prepared for coding.

Sample Characteristics and Sampling Techniques

The Sind (province of Pakistan) education administration, based in Karachi, consists of seven districts out of which four districts: east, west, north, and south schools responded for participation in the research. These schools are further divided into primary/secondary and higher secondary schools. To connect with the heads of schools through online platforms, district education officers (DEO) were initially approached for lists of head teachers. The focus of the study was on collecting data through a stratified sampling of schools. However, after selecting and contacting schools using stratified random sampling, very few responses were received. This was insufficient to produce reliable and valid results that could allow for generalization. Consequently, the authors had to switch data collection strategies and contact school administrators via convenience sampling techniques. The selection of participants was based on a convenience method during the quantitative phase, and researchers purposefully selected participants for the qualitative phase.

For quantitative analysis, data were collected from 205 (100 males and 105 females) from three different types of institutions (105 co-education-based schools, 47 boys-only schools, and 52 girls-only schools; one participant did not disclose the school setting). The qualitative part was completed through purposive sampling of one-on-one interviews with 10 participants. All participants had more than 10 years of job experience; data were then analyzed using standard procedures.

For qualitative analysis, it was decided to select participants based on their job status (e.g., teachers, headmasters, and DEOs from elementary, secondary, and college/higher secondary levels) to understand the diverse experiences of the participants. Participants who provided data for the qualitative part included two DEOs (one from primary school and the other from secondary and higher education), two headmasters (one from primary and the other acting as headmaster at secondary and higher secondary), and six teachers (one higher secondary, two primary, and three teaching at elementary and secondary levels). Of the six teachers described above, one teacher taught in a boys' schools, two in girls' schools, and three in co-educational schools (a classroom where girls and boys are not segregated).

Quantitative Data Analysis

For the quantitative analysis, SPSS version 20 was used, where the independent sample t-test, one-way ANOVA, and Pearson’s correlation were adopted to highlight the differences and to test the hypothesis.

Demographics of the quantitative sample

Demographic information showed that most of the participants from public-sector institutions were teachers (145), whereas 54 managers (heads of institutes) and six administrators (DEOs) also contributed to the study. Participants’ basic pay scale (BPS) and grade ranged from grades 9 to 20; however, most of the participants (55) had BPS 17 at the time of the data collection study.

Of the participants, 71% had obtained a Master's degree; however, 16% had higher qualifications, such as an M.Phil. or Ph.D. The most common group was secondary school teachers, from which 60 participants responded. Moreover, it was found that 51% of the participants had a social science background in comparison to 31% of participants from a natural science background. Forty percent of participants had more than 16 years of teaching experience. Table 1 below shows a brief demographic summary.

Instrument’s reliability

Questions to collect responses adopted from Social Role Questionnaire (Baber & Tucker, 2006) based on 13 questions (five reverse coded) where every statement response was collected on a 10-point Likert scale (0% = strongly disagree and 100% = strongly agree). This instrument was designed to manifest perceptions and beliefs about gender roles; lower scores indicate less traditional beliefs. Instrument reliability was ensured using Cronbach’s alpha value, which was 0.588 (> 0.5).

Quantitative Results for Traditional Beliefs

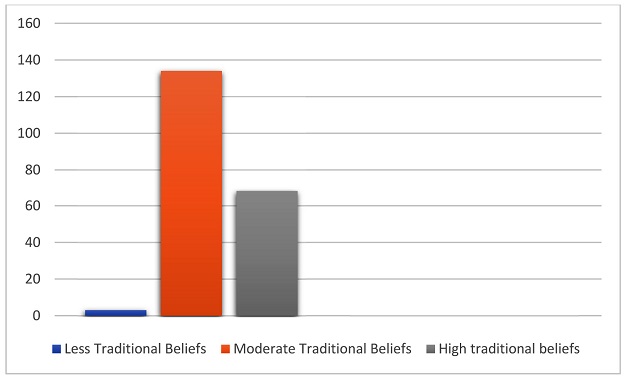

Traditional beliefs were analyzed by stratifying participants into three groups:

- > 70% scores = higher traditional beliefs

- Between 40% to 70% = moderate traditional beliefs

- < 40% scores = lower traditional beliefs

Gul et al. (2012) reported that the majority of educators valued traditional gender stereotypes. Data analysis is aligned with the study of Gul et al. (2012), which showed that only three participants had less traditional beliefs, 68 participants had a high level of traditional beliefs, and 134 participants had a moderate level of traditional beliefs (Refer to Figure 1).

Statistical analysis regarding demographic relationships with traditional beliefs was also conducted, and the results showed no significant relationship, as highlighted by Gul et al. (2012).

Gender Differences and Effect of Demographics on Traditional Role Beliefs

To determine the influence of gender on differences in opinions regarding beliefs about traditional social roles, an independent sample t-test was run. Data analysis indicated that there are no differences, and gender has no influence on beliefs, as the p-value is > 0.05. Levene’s test of equity assumes equal variance (see Table 2). This shows that males and females have similar beliefs about gender roles.

Similarly, to evaluate the impact of job status, type of school (co-education, pure girls’/pure boys’ school), father’s education, and mother’s education on beliefs for traditional roles, one-way ANOVA tests were run. These variables have no influence on traditional beliefs as no significant difference in mean values were observed and p-value > 0.05 (Refer to Tables 3, 4, 5, 6). Similarly, to determine the influence of fathers’ and mothers’ professions and marital status on beliefs, one-way ANOVA was also used, and no influences were found.

To assess the influences of BPS, qualifications, level of teaching, and experience of teaching beliefs regarding traditional social roles, Pearson’s correlation test was run using SPSS. The BPS was used as a basis for determining salaries. The higher the BPS, the higher the salary and status (primary to secondary); however, more experience may lead to higher salaries for similar BPS. Participants in this study had BPS 09, 10, 14, 15,..., 20. BPS 09 reflects newly recruited teachers in primary education (grades I to V), BPS 14 describes newly hired elementary school teachers (grades VI to VII), BPS 16 displays newly hired high school teachers (grades IX to X), and BPS 17 refers to higher secondary school teachers/college level teachers. The BPS and salaries are revised based on years of experience. Researchers also inquired about qualifications to compare whether beliefs are dependent on years of education, namely, 14 years of education (bachelors), 16 (Masters), 18 (M.Phil), and 21 years (Ph.Ds).

Results highlighted that the BPS, qualification, experience, and level of teaching have no influence on traditional beliefs regarding gender roles (Refer to Table 7).

Qualitative Findings

Qualitative data analysis was achieved through a standard procedure of transcribing interviews and reported under the headings of the themes generated after discourse analysis.

Gendered Aims

The aim of education is considered different for men and women, as the sample of interviewed participants reported that the expected outcome of education for male students is to prepare them for work whose returns could satisfy the family’s essentials. Education for girls aims at raising moral and uncritical women, who serve male dominance by being obedient daughters, devoted wives, and supportive mothers. Women cannot earn money from the work they do, so they are dependent on men for the fulfillment of their needs and desires. Therefore, men hold a superior position over women. Although consideration for financial support from women is given only when financial circumstances are dire, due attention is not given to overcoming dependency. It is believed that women should work only when asked to do so, as reported in the following quote:

Education attempts to enable men to fulfill their major responsibility of running the family with sufficient financial resources. However, educated women could be able to nurture their children with proper attention and help them in their studies. Also, when a husband is not self-sufficient in providing financial assistance, an educated lady performs a part-time job to support him.

Furthermore, it is expected that girls are not required to disclose their likes, dislikes, opinions, ideas, and take decisions for their lives. Education inhibits girls from thinking in innovative ways to achieve novelty. Active and assertive behaviors are disliked as well. One of the participants elucidated:

I loved society where daughters could not speak directly to their fathers, but nowadays they are adamant about achieving their desires.

It was observed that participants were against the separation and wanted to live in extended highly patriarchal families like the past, where orders were smoothly followed by younger women and women's protest of their rights were abhorred, which is inferred from the statement:

There is no patience now; parents were never asked for separation from abusive marital relationships before; schools need to teach girls ethics for well-being.

Based on these statements, it is assumed that education is intended to expand the roots of gender inequality. As opposed to contributing to economic progress, women are expected to strengthen family relationships by providing traditional feminine services.

Discouraging Higher Education

Gender development remains a neglected area. Analysis of the current study highlighted that boys' interest in higher education is served, while girls are neglected. Efforts to improve gender identity and reshape society through innovative gender-role perceptions have never been planned by urban educational institutions. Participants believed that the majority of public-sector students are poor, and due to limited financial resources, investment in girls' higher education is considered wasteful due to the lack of economic return to parents, as this is likely to be reaped by the in-law’s family (Qureshi, 2012). Most participants explained this as follows:

Spending money on daughters' higher education will not be fruitful in any way. As for boys, they are seen as old-age support to parents, even if they are non-compliant and disrespectful to them, but still, parents have to live with them and adjust to their misbehavior.

According to the findings, an inclination toward unexamined beliefs is one of the reasons behind the disfavor of girls in higher education. Dowries are thought to be mandatory in girls' marriages and are accumulated and saved by parents from an early age (Mughal, 2018). These situations cause families of low economic status to forego additional expenses on education. One of the participants reported:

Parents cannot spend more than dowry.

Another said that parents are afraid of being cursed for receiving an advantage from their daughter's earnings:

After daughters' marriage, we avoid taking any money from the daughter. We feel awkward even drinking water at the daughter's home. If there is no alternative and we are forced to eat in their homes, we compensate for it as soon as possible. However, parents who are careless of these things are misfortunates.

Also, girls are advised:

Fieldwork with men's NGOs is rarely acceptable; it is better to enroll in fewer investment courses for beauticians and seamstresses during hard times.

These responses challenged the role of education in girls’ empowerment. There has been no attempt to encourage girls to think about high-profile jobs or pursue a career based on educational accomplishments. Rather, girls are motivated to excel at traditional feminine tasks to maintain a culture of male superiority.

A Rigid Mindset

According to the interview analysis, the participants strictly adhered to traditional masculine and feminine roles, and never acknowledged the need to change social gender roles. Although housework is the most valued task for women, it is neither expected nor acceptable for men. It is also evident from the previous research that home responsibilities are considered loathsome to men (Rehman & Roomi, 2012) One of the participants explained:

Men cannot nurture children; this labor is predestined for women.

Another stated that:

As you have witnessed clips of men washing dishes, these jokes do not seem right since men cannot do that work continuously. You would rarely see men working as housemaids; we mean that it looks good when men portray masculinity while women depict femininity.

Another said:

It is also my observation that the household work is too much for women (ironing, cooking, cleaning, weaving, nurturing kids, etc.). I believe she should give one-sided attention to each kid, which is more than enough for them.

Some respondents added:

Women do more work than men.

In addition, the majority of participants disapproved co-education. They reported that a mixed approach to education diverts students' attention from their studies in the following ways.

Study age is very crucial that needs focus since the students are immature. This focus is no longer in the co-education environment, the separate institutes are better.

The above attitude has the effect of enlarging the gap between male and female students because educational institutions do not want to provide female and male students with a platform to share experiences and discuss gender-based taboos critically.

Teaching as a Feminine Profession

Researchers have found that educators believe there are very few opportunities for girls to pursue careers, and among those, teaching is considered the best fit (Siddiqui, Nazar, Hussain, & Ali, 2019). One of the reasons for the selection of teaching for women is the misconception that it is a peaceful profession, and the responsibilities of the job are relatively less than other jobs, so they will not interfere with their personal lives. One of the participants reported:

I believe peace is more significant than anything in the world. My younger sister is struggling at the post of bank manager, but she should consider teaching.

Another participant stated:

Teaching is the best profession for girls. I ask my daughter to pursue a career in teaching as I do because the working hours of teaching are less and teachers conduct three classes for only two hours; they are free the rest of the day.

One of the participants said:

My daughter has chosen a profession that requires her to work until evening. Long working hours make me worried so I try to convince her to change her line of work but she is adamant.

Based on the above responses, the participants indicate that women’s intentions of obtaining an education have led them to choose professions that require fewer working hours, are less challenging, and do not let them neglect their families. However, equal attention of both male and female adults toward family responsibilities has not been addressed. Initiatives have not been sought that would lead to improving marginalized girls' confidence and enabling them to choose careers related to their interests and strengths.

Discussion and Conclusion

The purpose of this study is to investigate how gender-based instruction is incorporated into mainstream education in Pakistan's metropolitan areas. The literature has revealed that throughout history, public-sector educational institutions have used their power and social positions to reproduce gender inequality (Islam & Asadullah, 2018). The results of the current study also support the literature and reveal that the majority of educators hold conventional gender-role beliefs, despite working in an urban setting where discriminatory beliefs are considered less significant than in rural areas, and very few (only three participants) held less traditional beliefs. In line with previous studies, the quantitative analysis of this study found that participants' traditional beliefs are not related to differences in their demographics, such as years of teaching experience, gender, or type of institution (Gul et al., 2012). In the same vein, different scholars have found similar teachers' stereotypical mindsets at different levels of teaching, that is, from the pre-primary to university level (Gul et al., 2012; Kalra & Sharma, 2019; Mahmood & Kausar, 2019; Pardhan & Pelletier, 2017). Similarly, Pearson's correlation in the current study has also shown that level of teaching has no influence on gender stereotype beliefs. Although most scholars have noted that demographics have no influence on a stereotypical mindset (Esen, Soylu, & Sagkal, 2019) research outcomes showed that parental education, designation, and qualification have a significant relationship with gender-role perception. In contrast to the study of Esen et al. (2019), the current research did not find any relationship between these variables. More in-depth studies are needed to uncover the reasons for the development of gender stereotypes in both urban and rural settings, and demographics or other factors should be studied in detail to determine their core causes.

The qualitative analysis has generated themes and insight toward gender discrimination beliefs, and using the CDA approach, the following themes have emerged:

- ・ Gendered aims

- ・ Discouraging higher education

- ・ A rigid mindset

- ・ Teaching as a feminine profession

Researchers such as Paulo Freire, and Bell Hooks have argued that schools are institutions that construct social realities and have greater impacts on the thought patterns of students. However, Bizzell (1991) mentioned that instead of reforming the minds of generations, they contribute to widening inequalities. The current study results also support Bizzell ’s (1991) mention of inequalities and the interview data have highlighted that the intended aim of education for girls is different from that for boys. Boys' education is considered vital to achieve a desired and valued social position and take part in economic contribution. In contrast, girls' education seems to help them acquire skills that develop them uncritically, into morally rich daughters, devoted wives, and responsible mothers, who could also bear the burden of the dual responsibilities of work and home when the husband is unable to cover family expenditures. It was found that teachers perceive that girls should engage in less challenging, low-earning jobs and, prove to be dependent, obedient daughters and mothers willing to sacrifice; accepting more home and kinship duties. Due to fewer assumed working hours, teaching is regarded as a feminine profession (Siddiqui et al., 2019; Ullah, 2016) and the best earnings platform for girls outside the home. According to Paulo Freire (1996, cited in Ziv, 2015), seeing teaching as a feminine activity and teachers as aunts underestimates the actual responsibilities of teachers in society. Along with the teaching profession, cultural arts are also suggested without acknowledging their interests and abilities. According to Kalra and Sharma (2019), gender-based violence and gender stereotypes abound in Indian schools, where teachers discourage girls from pursuing careers of their own interest. Women should maintain their status as being virtuous, compassionate, and willing to provide quality services to cherished kinship ties.

Participants also believed that young girls may spend time with textbooks that are gender-discriminatory, as expressed by Sultan et al. (2019). Teachers base their lessons on these textbooks, exaggerating the role and involvement of women in Pakistani society (Islam & Asadullah, 2018), which directly or indirectly harms the country’s education system and social structure. Moreover, gender discrimination continues to be mediated through education due to teachers' ignorance, unawareness, and inclusive approaches to social issues and social change (Giroux, 2014). McCullough (2017) argues that when girls stop being silent to resist oppression, schools propagate biased treatment toward them, and they are forced to accept and acknowledge male dominance. The conclusion indicates that participants ideally prefer a gendered society in both rural and urban areas, where men's social positions are considered superior and women's inferior and where important decisions should not be made by women without men's knowledge and consent (Hooks, 1989).

The consequences of this gendered mindset have been discussed by Faizi and Butt (2017), Mehmood et al. (2018), and Nausheen and Richardson (2018), who revealed that the percentage of girls in the labor market is very low, as most of them do not continue their education at a higher level even in urban contexts. Moreover, people in both rural and urban areas prioritize investments in dowries over educational opportunities for girls (Mughal, 2018), implying that educators are blind to the existing taboos that make girls unproductive and indecisive. A strong belief has been observed that women in affluent families are more inclined to perform only the traditional role, as balancing work and family life is one of the biggest challenges for them in patriarchal Pakistani society (Rehman & Roomi, 2012). However, at the same time, it is considered practical for women to work outside and fulfill their family responsibilities if needed.

Recommendations

Some of the recommendations made by the authors are as follows:

- ・ As many Islamic scholars have pointed out, the Qur’an clearly states the principle of equality among all humans. According to the Qur'an (including Qur'an 49:13, 3:195, 4:124, 16:97, 33:35), God created humans from males and females, and regardless of their empirical differences (such as race and gender), humans are regarded as equals by the Qur'an. God created men and women from the same soul as guardians of each other in a relationship of cooperation, not domination (Al-Hibri, 2000). It is recommended that events and training aligned with the concept of women's rights be organized according to the Qur’an and Sunah, as expressed by Al-Hibri (2000).

- ・ A law, policy, or program should include measures to encourage gender equality among its aspects to reduce imbalances and inequalities. It is possible to achieve these goals by promoting women's access in sectors where they are under-represented, such as education and professions associated with STEM, by encouraging their participation in decision-making, and by creating opportunities for them to serve in public administration, businesses, and care settings. Furthermore, gender statistics and studies should be promoted, and proactive steps should be taken to end gender-based violence.

Directions for Future Research

In rural areas of Pakistan, education and career opportunities for girls are even more limited than in urban areas. Future in-depth research studies are suggested to help understand how schools promote gender bias in these remote areas. Furthermore, only a small number of respondents from the education department of Pakistan participated in this study. Future researchers should gather a broader volume of data and examine gender inequalities even more critically at the administrative level. A random stratified sampling strategy is also recommended to obtain generalized results.

Acknowledgments

The authors greatly appreciate the reviewers who have dedicated their considerable time and expertise to improvise this paper from its submission to its acceptance. The authors would also like to thank Editage (www.editage.co.kr) for English language editing.

References

-

Afzal, M., Butt, A. R., Akbar, R. A., & Roshi, S. (2013). Gender disparity in Pakistan: A case study of middle and secondary education in Punjab. Journal of Research and Reflections in Education, 7(2), 113–124.

[https://doi.org/10.3126/ijssm.v3i4.15962]

- Ahmed. A, (2019). Pakistan ranked 151 out of 153 countries on the Global Gender Gap Index: World Economic Forum report. Retrieved August 6, 2022, from https://www.dawn.com/news/1522778

- Al-Hibri, A. (2000). An introduction to Muslim women’s rights. In W. Gisela (Ed.), Windows of Faith: Muslim Women Scholar-activists in North America (pp. 51–71). Syracuse University Press, New York, USA.

-

Alkin, M.C., & McNeil, J.D. (2001). Curriculum Evaluation. In J.S. Neil and B.B. Paul (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (pp. 3191-3195). Pergamon, Oxford, United Kingdom.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/02417-7]

-

Assari, S., & Caldwell, C. H. (2018). Teacher discrimination reduces school performance of African American youth: Role of gender. Brain Sciences, 8(10), 183.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci8100183]

-

Baber, K. M., & Tucker, C. J. (2006). The Social Roles Questionnaire: A new approach to measuring attitudes toward gender. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 54(7–8), 459–467.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9018-y]

-

Bizzell, P. (1991). Classroom authority and critical pedagogy. American Literary History, 3(4), 847–863.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/alh/3.4.847]

-

Daraz, U., Ahmad, A., & Bilal, M. (2018). Gender inequality in education: An analysis of socio-cultural factors and impacts on the economic development of Malakand, Pakistan. Liberal Arts and Social Sciences International Journal (LASSIJ), 2(2), 50–58.

[https://doi.org/10.47264/idea.lassij/2.2.6]

-

Durrani, N. (2008). Schooling the ‘other’: The representation of gender and national identities in Pakistani curriculum texts. Compare, 38(5), 595–610.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/03057920802351374]

-

Esen, E., Soylu, Y., & Sagkal, A. S. (2019). Gender perceptions of prospective teachers: The role of socio-demographic factors. International Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 11(2), 201–213.

[https://doi.org/10.15345/iojes.2019.02.013]

- Faizi, W.U.N., & Butt, M. N. (2017). Higher education for women in Peshawar: Barriers and issues. Al-Idah, 35(2), 72–84.

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed (M. B. Ramos, Trans.). New York: Continuum, 2007.

-

Giroux, H. A. (2014). When schools become dead zones of the imagination: A critical pedagogy manifesto. Policy Futures in Education, 12(4), 491–499.

[https://doi.org/10.2304/pfie.2014.12.4.491]

- Gul, S., Khan, M. B., Mughal, S., Rehman, S. U., & Saif, N. (2012). Gender stereotypes and teachers’ perceptions (the case of Pakistan). Information and Knowledge Management, 2(7), 17–28.

- Hooks, B. (1989). Talking back: Thinking feminist, thinking black. Boston: South End Press.

-

Islam, K. M. M., & Asadullah, M. N. (2018). Gender stereotypes and education: A comparative content analysis of Malaysian, Indonesian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi school textbooks. PloS ONE, 13(1), e0190807.

[https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190807]

- Kalra, D., & Sharma, A. (2019). Gender sensitisation: A catalyst to revamp the society. Journal of the Gujarat Research Society, 21(16), 491–500.

- Kapur, R. (2019). Gender inequality in education. International Journal of Transformations in Business Management, 4(1), 1–12. Retrieved May 16, 2020, from http://www.ijtbm.com

-

Mahmood, T., & Kausar, G. (2019). Female teachers' perceptions of gender bias in Pakistani English textbooks. Asian Women, 35(4), 109–126.

[https://doi.org/10.14431/aw.2019.12.35.4.109]

-

McCullough, S. (2017). “I Hope Nobody Feels Harassed”: Teacher complicity in gender inequality in a middle school. Girlhood Studies, 10(1), 55–70.

[https://doi.org/10.3167/ghs.2017.100105]

-

Mehmood, S., Chong, L., & Hussain, M. (2018). Females’ higher education in Pakistan: An analysis of socio-economic and cultural challenges. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 5(6), 379–397.

[https://doi.org/10.14738/assrj.56.4658]

-

Mitcho, S. R. (2016). Feminist pedagogy. In: M. Peters (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory (pp. 1–5). Singapore: Springer.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-532-7_235-1]

- Mughal, A. W. (2018). Investigating the issue of out-of-school children in rural Pakistan: Implications for policymakers (Doctoral dissertation). Loughborough University, UK.

-

Muhammad, A., Haq, Z. U., & Khan, I. (2018). Household discrimination in school enrolment in Pakistan: Does gender matter? Journal of Applied Economics and Business Studies, 2(1), 29–36.

[https://doi.org/10.34260/jaebs.213]

-

Mullet, D. R. (2018). A general critical discourse analysis framework for educational research. Journal of Advanced Academics, 29(2), 116–142.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/1932202X18758260]

- Nausheen, M., & Richardson, P. W. (2018). Gender and disciplinary differences in future plans of postgraduate students in Pakistan. International Journal of Gender, Science and Technology, 10(2), 338–361.

-

Pardhan, A., & Pelletier, J. (2017). Pakistani pre-primary teachers’ perceptions and practices related to gender in young children. International Journal of Early Years Education, 25(1), 51–71.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2016.1263938]

-

Qureshi, M. G. (2012). The gender differences in school enrolment and returns to education in Pakistan. The Pakistan Development Review, 51(3), 219–256.

[https://doi.org/10.30541/v51i3pp.219-256]

-

Rahman, S., Chaudhry, I. S., & Farooq, F. (2018). Gender inequality in education and household poverty in Pakistan: A case of Multan District. Review of Economics and Development Studies, 4(1), 115–126.

[https://doi.org/10.26710/reads.v4i1.286]

-

Rehman, S., & Roomi, M. A. (2012). Gender and work-life balance: A phenomenological study of women entrepreneurs in Pakistan. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 19(2), 209–228.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/14626001211223865]

-

Rogers, R., Malancharuvil-Berkes, E., Mosley, M., Hui, D., & Joseph, G. O. (2005). Critical discourse analysis in education: A review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 75(3), 365–416.

[https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543075003365]

-

Rosa, R., & Clavero, S. (2022). Gender equality in higher education and research. Journal of Gender Studies, 31(1), 1–7.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2022.2007446]

- Rotter, T. M. (2019). Gender inequality in Pakistan: Causes and consequences from feminist and anthropological perspectives (Master dissertation, Universitat Jaume I). Retrieved August 7, 2022, from http://repositori.uji.es/xmlui/handle/10234/183266, .

- Sahibzada, H. E., Tayyab, M., & Khan. K. (2019). A comparative study of gender inequality in education pertaining to economic and socio-cultural aspects at secondary school level in district Swabi. University of Wah Journal of Social Sciences, 2(1), 75–94.

- Salik, M., & Zhiyong, Z. (2014). Gender discrimination and inequalities in higher education: A case study of rural areas of Pakistan. Academic Research International, 5(2), 269–276.

-

Siddiqui, S., Nazar, N., Hussain, S., & Ali, W. (2019). Impact of mother’s teaching profession on children’s growth: A study on teaching mothers in metropolis city of Pakistan. Journal of Independent Studies & Research: Management and Social Sciences & Economics, 17(2), 139–154.

[https://doi.org/10.31384/jisrmsse/2019.17.2.10]

-

Smith, F., Hardman, F., & Higgins, S. (2007). Gender inequality in the primary classroom: Will interactive whiteboards help? Gender and Education, 19(4), 455–469.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250701442658]

-

Stamarski, C. S., & Son Hing, L. S. (2015). Gender inequalities in the workplace: The effects of organizational structures, processes, practices, and decision makers’ sexism. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1400.

[https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01400]

-

Sultan, R. S., Shah, N., & Fazal, A. (2019). Gender representation in public school textbooks of Balochistan. Pakistan Journal of Applied Social Sciences, 9, 55–70.

[https://doi.org/10.46568/pjass.v9i1.328]

- Tenvir, F. (2015). The educational experiences and life choices of British Pakistani Muslim women: An ethnographic case study (Doctoral dissertation). University of Worcester, UK.

- Ullah, H. (2016). School teaching as a feminine profession: The legitimization and naturalization discourses in Pakistani context. In Papers from the Education Doctoral Research Conference Saturday 28 November 2015 (p. 122-130). Retrieved May 16, 2020, from http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/schools/education/courses/postgraduate-research/doctoral-research-conference.aspx

-

Van Dijk, T. A. (2006). Discourse and manipulation. Discourse & Society, 17(3), 359–383.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926506060250]

-

Winslow, S., & Davis, S. N. (2016). Gender inequality across the academic life course. Sociology Compass, 10(5), 404–416.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12372]

- Wodak, R., & Meyer, M. (2009). Critical discourse analysis: History, agenda, theory, and methodology. In W. Ruth and M. Michael (Eds.), Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis, 2nd revised (pp. 1-33). Sage, London, United Kingdom.

- Zarar, R., Bukhsh, M., & Khaskheli, W. (2017). Causes and consequences of gender discrimination against women in Quetta City. Arts and Social Sciences Journal, 8(3), 1–6.

-

Ziv, H. G. (2015). Feminist pedagogy in early childhood teachers' education. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 3(6), 197–211.

[https://doi.org/10.11114/jets.v3i6.1072]

Biographical Notes: Preeta Hinduja serves as a visiting faculty member at different universities in the metropolis city of Karachi, Pakistan. These universities include Sindh Madressutul Islam University, Iqra University and Allama Iqbal Open University. She has completed an M.Phil. in Education from Iqra University, Karachi, Pakistan, where she is continuing her Ph.D. in Education. Her research interests include assessment and evaluation, educational psychology and teacher education. Email: hindujapreeta@gmail.com, Orcid ID: 0000-0003-4316-3734

Biographical Notes: Sohni Siddiqui completed her M.Sc at Karachi University and was then admitted to the profession of teaching. Her keen interest in education led her to pursue further studies at Iqra University Karachi where she completed her M.Phil. in Educational Sciences. She has over 20 years of experience in teaching and training and has worked with students from Pakistan, the U.A.E., and the U.K. In addition, she is an author and external reviewer for a number of national and international educational journals. At the moment, she is serving as an external researcher at the Technical University of Berlin conducting research on teachers' professional development. Email: s.zahid@campus.tu-berlin.de, Orcid ID: 0000-0002-4001-5181.

Biographical Notes: Mahwish Kamran serves as a lecturer at the Department of Education and Social Sciences at Iqra University, Karachi Pakistan. She has completed an M.Phil. in Education from Iqra University, Karachi, Pakistan, where she is continuing her Ph.D. in Education. Her research interests include inclusive education, curriculum development and special education. She has published research papers in International Journal of Organizational Leadership and Disability and CBR and Inclusive Development. She has attended and presented research papers at many national and international conferences. Email: mahwish.siddiqui@iqra.edu.pk, Orcid ID: 0000-0002-0572-1603