Professional Socialization and Glass Ceiling Perceived by Women Sports Leaders Working in Sports Centers in South Korea

Abstract

The purpose of this study is to explore the biographical understanding of professional socialization and the glass ceiling through occupational socialization theory as perceived by women sports leaders working in sports centers and to provide improvement plans accordingly. Participants consisted of six women sports leaders working at sports centers in metropolitan cities of South Korea (two in taekwondo, two in pilates, one in yoga, and one in fitness; one in her 50s, two in their 40s, and three in their 30s). Data collection was conducted using one-on-one semi-structured interviews, observations, and field notes, and the collected data were analyzed using constant comparative analysis. A result was that the women sports leaders experienced gender-discriminatory behaviors and male-centered culture in the field of physical education from childhood, which acted as a temporary obstacle to their occupational choice as a sports leader. Further, such gender-discriminatory experiences continued in the stage of professional development as well as in the current position, functioning as an impediment factor in enhancing their professionalism and status. The experiences were divided into five key themes as follows: (1) sports activity in childhood and career milestones, (2) professional development and limitations as a woman sports leader, (3) discrimination and injustice against women sports leaders in sports centers, (4) institutional inequality against women’s labor in sports centers, and (5) lack of sports infrastructure and governmental policy support for women. Implications and plans for improving the occupational stability, professionalism, and promotion of women sports leaders were discussed in detail.

Keywords:

Women leaders, glass ceiling, professional socialization, physical education, sportsIntroduction

The educational level and entry into society of women around the world continues to be particularly high over time (Batson , Gupta, & Barry, 2021). Likewise, with the development of laws and institutions in each society, there is an increasing tendency for women to be treated equally with men and to exercise equal responsibilities and rights in all areas of society (Parihar & Bannerjee, 2021). However, in South Korea, although the levels of education and social and economic activity of women are gradually increasing, it is not apparent that the status and roles of women have greatly improved (Min, 2021). For example, among member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), South Korea is recognized as a country where the glass ceiling prevails and a very high incidence rate of related events prevents women from advancing or improving their status in the workplace (Park & Kim, 2020). Specifically, the glass ceiling refers to an invisible barrier in an organization that prevents women or social, racial, and cultural minorities from advancing to high positions. In particular, it can be defined as a critical term to mean that promotion to a higher position is blocked because of implicit prejudices and practices and negative perceptions in the organization even if women have sufficient abilities and qualities (Mujahed & Atan, 2017). Practically speaking, the glass ceiling indicates a hidden and intangible barrier in the organization that represents the social inequality and poor treatment of women by the negative perceptions of job ability and discriminatory (male-dominated) culture and practices (Mujahed & Atan, 2017). In that regard, the glass ceiling is likely to occur in a workplace (e.g., sports organizations and sports centers) that limits the promotion of women; it appears in gender-based discrimination against women including a male-oriented culture, behavior, and beliefs (Galloway, 2012).

In South Korea, one area where women’s socio-economic status is perceived as low is in the sports domain (organizations), where the proportion of women administrators, executives, and leaders is significantly lower than that of men (Lee, 2020). Specifically, the proportion of women executives in the Korean Sport & Olympic Committee, various sports and affiliated organizations, and provincial sports federations is less than 10% (Lim, 2022). Even in elite sports leaders, the percentage of women directors in volleyball and basketball remains below 8% (Lim, 2022). This phenomenon can be interpreted as clearly revealing the limitations to women attaining their potential and the difficulties in achieving social success because the discrimination and gender-inequality practices against women’s abilities, social roles, and status are deeply embedded in Korean sports. In fact, due to such a male-friendly culture and discriminatory behavior and treatment in Korean sports organization (e.g., sports administration including sports centers and clubs), the opportunities for women to demonstrate their professionalism and rise in status have been decreasing (Nam, 2019). Furthermore, there are frequent violations of women’s rights and dignity, thus a high level of action for their protection at the social (government) level is required from the organizations of women’s sports areas to increase the actions needed to solve the problem (Park & Choi, 2021).

Occupational socialization theory, which deals with the occupational positions and roles of members in the organization of a society and aspects of socialization, is defined as a theoretical perspective that covers personal growth experiences for professional development related to the process of adapting to the current job (Pennington, 2021). The focus is on the process of individual growth into professional socialization through life-history experiences and learning processes for professional identity; the process is largely divided into three stages. The first stage is called anticipatory socialization (acculturation ), which refers to personal experiences such as learning activities and role models during school years (elementary, middle, and high school) that influence an individual’s occupational choice. The second stage is defined as a process of professional socialization, which refers to a process of cultivating expertise in knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values from higher education institutions or specialized educational institutions in relation to a current position. The third stage, organizational socialization, is the process of adapting to colleagues and social environments, performing tasks and roles, and continually developing professionalism in the organization after entering the current position (Romar & Frisk, 2017). Research has supported a perspective on sequential socialization associated with the three kinds of occupational socialization that influence persons to enter the field of sports (Richards & Wilson, 2020). There are also previous studies based on occupational socialization theory that describe gender stereotypes and the glass ceiling as a significant barrier to the professional development of women in sports (Richards & Wilson, 2020).

Koo and Kwon (2011) explored the socio-cultural prejudices against women workers in Korean sports organizations and the problems related to the glass ceiling for women workers. They discovered that the male-dominant and patriarchal Confucianism in Korean society and the aggressive, hierarchical, competitive, and collectivist culture of Korean sports organizations made it easier for men than women to develop and to stabilize their professional life. It was also found that men were more well integrated into the dominant and managerial roles and practice than women. Further, Maeng and Lee (2017) examined the obstacles for professional development recognized by women sports personnel entering the workplaces in Korean society and explored ways to overcome them. In the results, the study participants pointed out that the main factors limiting professional development and promotion were the lack of women’s decision-making rights in sports organizations and their male-centered organizational culture. To change this, they emphasized the need for implementation of a quota system for women executives in sports organizations and provision of a system that allows them to compete on equal conditions with men in terms of the capabilities and qualifications necessary to the organization. In a similar vein, Lee (2020) probed the glass ceiling perceptions experienced by women employees in sports-related organizations through in-depth interviews. As a result, the participants perceived Confucian culture and the fixed gender roles in Korean society as having a negative influence on their work productivity and promotion. Moreover, they experienced their contribution to the organization as relatively reduced because they were not assigned to major tasks, and consequently, were deprived of opportunities for promotion.

The preceding studies shed light on multiple conditions and perspectives on social discrimination and status (i.e., gender-based discrimination and inequal treatment) experienced by women workers in sports and the deprivation of promotion opportunities i.e., the glass ceiling. However, previous studies have not identified what motives and life experiences women sports personnel have who entered sports and what kinds of efforts they made to get the job they currently have. Moreover, there are very few occupational socialization studies that have investigated the experience of the glass ceiling from the perspective of women sports leaders in a sports education organization. In particular, although there are a few studies exploring the occupational socialization process of women physical education teachers (Lee, 2020), it is rare to find research that deeply illuminates and explores the occupational socialization process of women sports leaders in sports centers, known for a male-dominated organizational culture and deeply ingrained social and economic sexist behaviors. Finally, there is no study that investigates what women sports leaders in the sports centers of South Korea have experienced through gender-based discrimination and how they dealt with and overcame it in terms of their own biographical context. Therefore, this study, grounded in occupational socialization theory, aims to examine the life-history experience (i.e., occupational acculturation) of women sports leaders who made career choices as a sports leader, the difficulties and limitations experienced in the process of professional development and in their current position and provide implications and improvement plans accordingly. Specifically, these research questions guide this study: 1) Why do women choose a career path as a sports leader? 2) What have they done to pursue and develop their profession as a sports leader? 3) What kinds of sexual discrimination and glass ceiling have they experienced during their professional development and current position? 4) What have they perceived through the sexual discrimination and glass ceiling and how have they dealt with the limitations imposed by these?

Methods

Participants

The participants of this study consisted of six women sports leaders working at sports centers in metropolitan cities of South Korea. The distribution by age was one in her 50s, two in their 40s, and three in their 30s, ranging from 38 to 50. All participants have more than ten years of teaching experience, including two Pilates leaders, two Taekwondo leaders, one Yoga leader, and one Fitness leader. At the time of this study, three leaders were working as center directors, two as managers, and one leader as a sports instructor. In addition, all participants held at least a bachelor’s degree, and five held advanced degrees (Master’s or PhDs) in related disciplines. The study participants were recruited by means of a purposive sampling method in which subjects in a specific group were judged to be able to express their personal thoughts and experiences well in relation to the research topic (Campbell et al., 2020). To protect the personal information of the participants, the names of the participants in this study were replaced with pseudonyms.

Data Collection

The researcher conducted formal interviews with the study participants who were contacted individually to confirm their intention to participate in this study; they voluntarily agreed to an appointment for a personal interview. Before the interview began, the participants had the purpose and use of the study as well as the questions and procedures explained to them in detail, and the interview was recorded using an audio recorder. The interview was conducted using a semi-structured interview technique, which included a continuous question-and-answer format based on the researcher’s question and an interviewee’s responses. The interview consists of a total of seven questions in line with the purpose of the study and specifically focusing on the occupational acculturation stage (anticipatory socialization), the professional education course stage (professional socialization), and the individual adaptation stage to the current position (organizational socialization). Grounded in the process leading up to their current positions as women sports leaders, the interviews were mainly concentrated on the inequality and unfairness related to gender discrimination in the sports organization, the limitations of professional development, and the perceptions and experiences of the glass ceiling. The interviews were carried out individually with the study participants and each interview took 40–60 minutes. Each interview was audio-recorded, and all interview data were transcribed using Microsoft Word. Further, the researcher took several observations at the sports centers for which the participants were working and wrote field notes to gather detailed information on the participants’ behaviors and attitudes and to make adjustments corresponding with the interview. The researcher completed the institutional review board course prior to this study, and the university review board for research with human subjects approved the collection of the study data prior to the research.

Data Analysis

The collected data including interviews and field notes on observations were analyzed using the constant comparative method, which means the researchers sort and organize the items of raw data into groups according to their attributes and arrange the groups in a classification pattern to develop a theory that integrates the data (Corbin & Strauss, 2014). To describe the analytic process in detail, first, open coding was carried out by a careful and meticulous reading and review of the multiple data together by the researcher and an expert having extensive professional knowledge in relation to the research area; meaningful words or phrases related to the research topic were identified. Second, the process of drawing the coding data into categories with similar contents was conducted. Third, the categories derived according to this process were integrated into a significant theme that best expressed the characteristics and patterns of content and domain between each category (Corbin & Strauss, 2014). Further, the researcher and expert continued the discussion process together until complete agreement on the main theme derived from the analysis process was reached.

Trustworthiness of Data

The trustworthiness of the research data was ensured using the following methods. First, the researcher conducted an triangulation process to maintain consistency and objectivity in data analysis by specifically explaining the subject and purpose of the research as well as the research method to the expert who participated in the analysis. In other words, the researcher and expert conducted the data analysis after becoming familiar with the constant comparative method. Second, a member check was conducted to check whether the contents stated in the data were consistent with the participants’ opinions; all participants responded that there was no problem with the interview contents. Third, a peer review was conducted with two other experts who did not participate in the analysis, but who had professional knowledge and experience related to the subject and methods of this study. They were asked to confirm and comment on the research analysis process and results. After being reviewed by the two experts, their appropriate and useful advice increased the credibility of the research results (Corbin & Strauss, 2014).

Results and Discussion

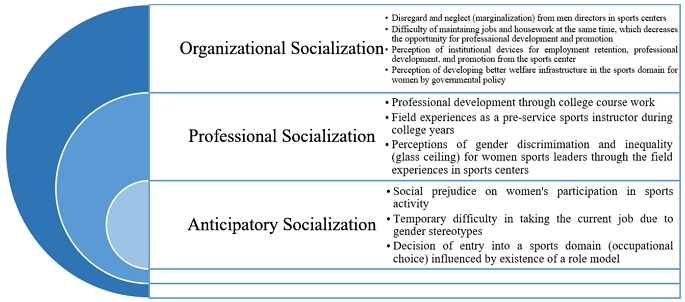

The study results were derived from the content and cases based on the three stages of the occupational socialization process. Specifically, in the stage of anticipatory socialization, it was found that the social perception and environment on participation in physical activity experienced in school years exerted a significant influence on participants’ career choice. In the stage of professional socialization, it was revealed that the experience of college education courses positively helped them pursue a career development goal or path and increase the professionalism associated with their current job. In the stage of organizational socialization, they each demonstrated their professional competence and abilities as a woman leader in the sports center to which they belonged. Nevertheless, as women, they identified the clear limitations and obstacles in maintaining a stable professional life, performing tasks in the organization, and achieving promotion opportunities. The perceptions were divided into three dimensions including personal, organizational, and social aspects. The five themes categorized according to each dimension are as follows:

Sports Activity in Childhood and Career Milestones

The participants revealed that society’s negative or unfavorable perception on participation in physical activity as a girl during childhood acted as a temporary difficulty in choosing their current career choice. In other words, it was natural and necessary to acquire and show gender role-oriented attitudes and activities from an early age and this made it difficult for them to participate in sports activities and enjoy them. At the time, this did not have a positive effect on the path they took to their current career.

When I was young, I was a little afraid to participate in sports activities such as Taekwondo as a woman, and there was a time when it was far from physical education because it was common to have a modest and feminine career choice. However, I came into contact with Taekwondo in my youth by chance and met a wonderful master, so my personality improved. Further, my career choice had changed to the field of Taekwondo. I am currently working as a Taekwondo director, and the proportion of female students in my gym is high. I think it’s because women instructors care is more meticulous and friendly t than men instructors... It is emphasized a lot that women can develop their mind, body, and character through physical activities such as Taekwondo. (Jung-Ah Kim, Taekwondo director)

The case can be interpreted as proof that the universally preconceived notions of women’s social activities and roles in Korean society promoted the lukewarm attitudes and experiences of the participants regarding engaging in sports activities; these functioned as a temporary obstacle for her current career choice. However, she indicated that if socializing agents such as sports leaders act as good role models, the perception of participating in sports can change for the better. Such perceptions eventually acted as the decisive momentum to be a taekwondo coach in one case.

To be honest, I did not often participate in physical activity throughout [my] school years, and I also did not major in physical education. However, after I met my husband, I entered into the field of Taekwondo, and I am currently working as a Taekwondo instructor. At that time when I was young, the social perception and atmosphere were very different from now for women to be interested in and participate in fighting sports, such as Taekwondo. Also, in my case, I did not dare to participate because I was afraid of the impression of a Taekwondo director... I am currently teaching students as a woman instructor, and parents like it very much in terms of kinship and physical caring. I think they trust me because I am a woman. In my opinion, women instructors can be advantageous in the future if they have expertise in that area. (Youn-Jung Ko, Taekwondo instructor)

This quote also added that the negative perceptions of engaging in sports activities could be positively changed by the influence of a major socializing agent such as family members. She illustrated that although the experience of participation in physical activity in the past was unfamiliar and not enjoyable, support and help from her husband positively impacted her career decision to engage in her current occupation.

Social norms were perceived through a gender-stereotyped lens when respondents were expected to play gender roles during childhood. In particular, the women sports leaders were negatively affected by social prejudices during the anticipatory socialization process relevant to forming a career choice. However, support from social environments such as major others (e.g., a role model) worked as a milestone for positive changes in such perceptions.

Professional Development and Limitations as a Woman Sports Leader

The participants experienced the process of professional development during university years when majoring in physical education. Specifically, they learned professional knowledge and skills related to sports activities and gained practical experiences in teaching diverse sports activities as a preservice instructor. Through such experiences, they also recognized there was gender discrimination and inequality for women instructors in sports.

Of course, I thought that I had professionalism through the process of majoring in physical education in college and learning and practicing instructional techniques. However, during college years when I got a part-time job for teaching sports activities, I realized that continuous effort is required in order to teach well in the actual field. In particular, there is a tendency to be compared to men sports instructors, so it is necessary to strive to improve one’s professionalism as a woman. Furthermore, this field is mostly run by men, so women can only survive and rise to a higher position by improving their own abilities. (Jung-Min Lee, Yoga director)

Lee indicated that she had learned instructional knowledge and skills in university and had gained practical experiences in coaching sports activities. Meanwhile, she recognized the main positions in sports centers were mostly occupied by men, and that it was difficult to advance to a higher position because of gender-discriminatory perceptions regarding the woman’s relatively undervalued ability during practical activities.

Although I got a bachelor’s degree as a sports leader, I went to graduate school to be more professional and to rise to a higher position. Compared to men instructors, I recognized the need to improve my educational ability and professionalism. Particularly, compared to the men instructors, the salary was lower and the treatment was not good. I thought the best way to overcome these limitations was to study further and get professionally prepared. It seemed to me that satisfaction with salary and work would increase if I went up to a higher position through such professional development. (Joo-Hee Nam, Fitness manager)

Nam also emphasized that pursuing higher education and improving professionalism were needed to enhance her work ability and to reduce the relative inequality of women sports leaders. Actually, she felt sexually discriminated by a lower wage for women, and this led her to pursue higher education.

Although I had improved teaching knowledge and practice in physical education field and got some experiences to teach several sports activities during college years, it is important to improve professionalism, specifically for women leaders. In light of my experiences, men sports leaders can be promoted easily if they sail with every wind, but as a woman sports leader, professionalism and distinction in educational methods and techniques are required to rise to a higher position. (Jin-Ah Seo, Pilates manager)

Likewise, Seo realized it was crucial to improve professionalism even if she developed practical knowledge and skills during her college years. Further, she noticed it was tough to advance her position compared to men due to a male-friendly culture in sports. For that reason, she was looking for a solution to deal with the limitation by improving her own instructional techniques such as a change in teaching strategies.

The participants mainly improved their professionalism in the university and acquired practical experiences in coaching sports activities. However, through such experiences, they also recognized that gender-based discrimination and stereotyping existed in the sports centers, and further that awareness of their ability on the job was underestimated and even received a relatively lower wage. In light of this perception, they stated that the strategies of getting into graduate school and enhancing professionalism were needed to reduce the relative inequality and to promote their own status.

Discrimination and Injustice Against Women Sports Leaders in Sports Centers

The men directors of the sports center had a perception of women sports leaders that was not as a partner in organizational tasks and activities, but rather as a member with insufficient or inferior competence. Such perceptions in the organization functioned as an impediment to women leaders’ work performance and competency, which undermined their task efficiency.

I think the place where I worked was a bit disrespectful of women sports leaders. To explain with an example, how much can women do? The sports center director seemed to respect gender equality on the surface, but the reality was very different. Also, he treated the women sports instructors unequally in terms of work, promotions, and salary. That was the main reason I quit the sports center. (Min-Ah Jung, Pilates director)

According to Jung, the sports center operated in a male-centered hierarchical structure, and women instructors did not get favorable recognition of their job performance; this was connected to a judgment on their ability and promotion. Actually, she reported that the male director ignored the abilities of women instructors, and this demotivated her and undermined her efforts and contribution to the sports center, which led her to quit the job.

The person who conducts the position change of the employees in the sports center is the director, and the director is mostly a male. So even if a woman leader has good ability, it is not easy to be promoted to a major position. In particular, if the director majored in physical education, such a tendency is stronger. I think it’s because the men directors are used to the culture of Korean men who can communicate easily with each other. That is, the Korean men have a drink together and shake off something they do not like or conflict with each other. It seems like that kind of sexist culture constantly persists in the sports center. (Jung-Min Lee, Yoga director)

Similar to Jung, Lee found that the sports center was not socially and emotionally supportive of women leaders and discriminated against women advancing toward leadership positions. Specifically, she discovered that the women leaders remained objectively underrepresented in the management or leadership positions of the sports center because the male-dominated culture and customs prevailed in it.

At the sports center where I worked in the past, there was unfair discrimination against women sports instructors. As it was a fitness activity, men instructors were considered to be in good physical condition and had an advantage in coaching and public relations, so there was discrimination in employment, work, and promotion against the women instructors. But I could not accept it. I taught competently the center members and handled membership maintenance, management, and related tasks well without any problems. However, discrimination existed in ascending to a managerial position. I mean a male instructor was promoted to the manager’s position. I felt that the director was prejudiced against women and had unfair standards for promotion. (Joo-Hee Nam, Fitness manager)

Likewise, Nam pointed out that the work disparities were not explained by job-related characteristics of the instructors, but by gender differences. That is, professional knowledge, skills, and past experiences were considered invalid for the women instructors. She indicated that no matter how much knowledge or experience the women instructors had, they were not likely to have high professional aspirations for promotion. Importantly, the condition contradicted the women leaders’ belief that dedication and hard work would lead to a better life.

The women leaders revealed that the gender-biased operation acted as an impediment in enhancing the sense of unity with the organization. That is, they reported enthusiasm, a sense of belonging, and attachment to the organization were decreasing due to the invisible discriminatory treatment, which in turn had a negative effect on loyalty and promotion. From recorded observations by the researcher, the women leaders showed a high level of passion and energy for teaching their clients and tried to exert their professionalism and ability for the development of the affiliated centers. However, because of the neglect and discriminatory treatment from men directors and colleagues, their professional capacity and confidence were unstable and damaged, which reduced not only assimilation into the organization but also their opportunities for promotion.

Institutional Inequality Against Women's Labor in Sports Centers

Through the work experiences in the sports centers, the participants emphasized that the burden of childbirth and childcare was the most negative factor related to their job stability, professional development, and promotion opportunities. To overcome this, they expressed their belief there must be a change in the social perception of traditional gender roles.

Currently, in Korea, women are receiving unequal treatment in relation to employment, work, and status at work due to childbirth and parenting. In my case, in the past, I was forced to quit my job and leave because of the issues. I mean I had to have a childcare leave, but it was not allowed that a colleague could take my job (member guidance and management). I understand the situation, but the director hired another coach to fill my position. In fact, the director could hire a coach on a temporary basis to take care of me... It completely depends on the will of the director. (Jung-Min Lee, Yoga director)

Lee complained about the lack of consideration and support in the sports center in reconciling housework and job for a woman worker and disclosed that it resulted in career interruption and considerable difficulty in returning to her original position. Many of the hardships that the women leaders encountered derived from the acceptance of socially expected norms and roles.

The problems of childbirth and childcare make it difficult for women to have job stability. Further, compared to men, career development is difficult for women because they have to deal with both housework and the job, which then does not make it easy to continue their work and develop professionalism. Moreover, it is very difficult to get a promotion opportunity. I have had that experience, so I try to preferentially hire women coaches who have had their career cut off due to childbirth and childcare if they apply. I think it’s because I have a strong desire to give an opportunity to them as the same woman. They have been disconnected from coaching and related work for a while, so the chances of being rehired are relatively low. It reminds me of my past experiences... (Jung-Ah Kim, Taekwondo director)

Kim also indicated that gender-based discrimination against women leaders in sports areas is prevalent. She discovered men and women coaches are treated differently in terms of work and promotion due to gender-stereotyped roles rather than an individual’s ability or job performance. It led her to allocate more hiring opportunities to women coaches as a strategy for attaining gender equality.

There are many cases where women sports instructors are not hired by sports centers due to childbirth and childcare. Although I am currently working as a director, in the past, I temporarily stopped my career due to childcare, but since then, I have been discriminated against in terms of salary and job assignments at the sports center. In particular, in the case of Korea, it is a reality that women engaged in sports organizations are at a disadvantage in maintaining their professional life and improving their status due to childbirth and childcare. It looks like the situation needs to be fixed quickly. (Min-Ah Jung, Pilates director)

Jung added that women’s roles based on gender such as childbirth and childcare were a burden and an obstructive factor for women leaders in developing professionalism and getting promoted. She criticized the inequality that continues to exist in Korean society, and how troublesome it is for the women instructors working in the sports center. Accordingly, she urged effective and substantive action to abolish such gender-based barriers.

With regard to having to perform both work and housework at the same time, the women sports leaders strongly insisted there was a need for an institutional device that could protect them from being disadvantaged in their employment when facing problems such as childbirth and childcare. The results revealed that it is an important issue for the sports centers to establish effective plans for operating a system that guarantees women’s employment, career development, and promotion at each site to enable them to grow into professional leaders.

Lack of Sports Infrastructure and Governmental Policy Support for Women

Interestingly, the women sports leaders mentioned women’s participation in sports activities would increase only when the sports infrastructure for women in Korean society is well established; this could greatly contribute to enhancing the level of their employment and status. Further, they highlighted the fact that their welfare should be guaranteed and improved through policy support at the social (government) level because enhanced welfare is directly related to professional development and promotion.

As a sports leader as well as a mother in a family, I teach and guide my daughter. Not a long time ago, my daughter had a Taekwondo match, and we went to a local Taekwondo gym together. After arriving, I was in a hurry to breastfeed my baby, so I looked for a nursing room, but I could not find it, and I fed her in a warehouse. Obviously, there were different types of people to participate in and watch the match, but there was no facility or space to take care of a baby. Although the times have changed a lot, I felt that the sports facilities were still structured around men. That is, it seems that there is still insufficient consideration given to improving the sports infrastructure for women. After all, I think that the male-centered culture and gender-discriminatory infrastructure of the sports domain have a negative impact on the employment and promotion of women sports leaders. (Jung-Ah Kim, Taekwondo director)

Kim provided a perspective that the male-biased structure and culture of sports environment (e.g., facilities) were deeply embedded in the Korean society, which solidified exclusion and disregard for women. She viewed this trend as one reflected in the overall sports domain as well as in the sports centers, pointing out that gender role-oriented work and gender-discriminatory behaviors are still emerging.

In the case of Korea, it is clear that women workers are being discriminated against because most of the heads in the sports organizations consist of males. It can be said that the male-dominated culture in the sports domain is still deeply entrenched. Through the governmental policies such as a quota system for women executives in sports institutions and organizations, the condition for women workers’ employment, promotion, and welfare would be enhanced ... Likewise, policy and sufficient support for childbirth and childcare welfare could be provided. (Min-Ah Jung, Pilates director)

Jung also identified that the continually male-dominated culture in Korean society impacted the women instructors’ marginalization or exclusion in the sports organization. The issue had led her to perceive differential treatment (i.e., promotion and welfare) between women leaders and their men colleagues, thereby increasing the perception of a glass ceiling in the sports center. Consequently, she insisted that the government should establish gender equality policies including a quota system for women executives and some strict regulations to lessen the burden of gender-based activity (e.g., childrearing).

The women leaders described male-centered hegemony as deeply embedded in sports activities, sports facilities, and their cultural elements throughout Korean society; consequently, the employment, promotion, and welfare for women sports personnel in the sports center constantly appear as irrational and absurd. Accordingly, they hoped that the government solves the problem through rational policies and administrative support. The summary of the study results was described as a sequential process (Figure 1).

Conclusions and Future Directions

The purpose of this study was to provide a biographical understanding of the professional career progression of women sports leaders working in sports centers using occupational socialization theory. Specifically, the study aimed to understand the difficulties and limitations of professional development and promotion in the participants’ current position given the glass ceiling and to discuss improvement plans accordingly. As a result, the perception of gender discrimination was confirmed from their childhood when they entered the field of physical education, and it also contained the experience of naturally acquiring and adapting to male-dominated hegemony and culture in the process of professional development and organizational socialization. Such gender-discriminatory occupational socialization experiences in sports repeatedly occurred not only during their school years but also during their current working life as a sports leader, and this acted as a major obstacle to enhancing their occupational stability, professionalism, and status in the sports centers. Moreover, the women sports leaders commonly recognized the existence of the glass ceiling in Korean society, and this trend was stronger for the women leaders in the sports domain where it functioned as a significant disadvantage to achieving stability and development in their professional life. Further, women leaders indicated that gender role activities including marriage, childbirth, and childcare worked as decisive factors that caused career interruptions and job changes and also acted as serious barriers to professional development and promotion.

In comparison to previous studies, the results of the present study identify the sexist perceptions and prejudices regarding the abilities and competencies of women sports leaders, the inequality of their employment and treatment in sports centers, and the lack of a sports infrastructure for women’s welfare as crucial issues needing improvements. To effectively deal with such problems, the findings suggest that institutional support (i.e., legalization ensuring employment stability and rise in status) from the sports center at each site as well as sports welfare policy and government-provided infrastructure for women should be sufficiently developed and implemented so that women sports leaders do not suffer from gender role barriers and are not disadvantaged in professional development and promotion. In reference to the sports welfare policy for women, according to the International Olympic Committee’s Gender Equality and Inclusion Report (2021), creating an environment that is respectful and welcoming to women coaches in sports where they feel confident to be themselves and make a meaningful contribution is important because it is key to establishing a more inclusive and peaceful society.

Although this study provided meaningful implications in relation to the professional socialization process of women sports leaders in the sports center, there are some limitations in the research results that cannot be overlooked. As the participants of this study were composed of women leaders of several specific sports working at sports centers in big cities of South Korea, it may be difficult to generalize the study results to women sports leaders engaged in other regions and different types of sports. In addition, because the results were derived from interviews with the research participants at a given time and several observations, it might be difficult to ensure external validity. Therefore, future research needs to explore the occupational socialization process of women sports personnel in different institutions and sports and to identify factors that hinder professionalism, gender equality, and promotion through a mixed method study. A more multifaceted approach will be of great help in providing information to heighten the professionalism and status of women working in various types of sports organizations and to enhance equitable gender treatment.

References

-

Batson, A., Gupta, G. R., & Barry, M. (2021). More women must lead in global health: A focus on strategies to empower women leaders and advance gender equality. Annals of Global Health, 87(1), 67.

[https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.3213]

-

Campbell, S., Greenwood, M., Prior, S., Shearer, T., Walkem, K., Young, S., ...& Walker, K. (2020). Purposive sampling: complex or simple? Research case examples. Journal of Research in Nursing, 25(8), 652–661.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987120927206]

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2014). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

- Galloway, B. J. (2012). The glass ceiling: Examining the advancement of women in the domain of athletic administration. McNair Scholars Research Journal, 5(1), 6. doi:https://commons.emich.edu/mcnair/vol5/iss1/6

- International Olympic Committee (2021). Gender equality & inclusion report 2021. Switzerland: Maison Olympique.

- Koo, C. M., & Kwon, S. Y. (2011). Sports in society. Seoul: Daehan Media.

-

Lee, W. M. (2020). Glass ceiling experience of women administrators in sport organizations. Korean Journal of Convergence Science, 9(2), 20–33.

[https://doi.org/10.24826/KSCS.9.2.2]

- Lim, S. M. (2022). Gender role identity, sexism, and gender equality in sports: Suggestions for creating a sports environment without gender discrimination. Sports Science, 159, 12–17.

-

Maeng, L. S., & Lee, W. Y. (2017). A study on the activation plan of social advancement for women sports athletes. The Korean Journal of Physical Education, 56(5), 119–129.

[https://doi.org/10.23949/kjpe.2017.09.56.5.10]

-

Min, S. W. (2021). The relationship in glass ceiling, work engagement, and service orientation among female hotel employees. The Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 21, 12(2), 1783–1796.

[https://doi.org/10.22143/HSS21.12.2.125]

-

Mujahed, F., & Atan, T. (2017). Breaking the glass ceiling: Dealing with the attitudes of Palestinians toward women holding leading administrative positions. Asian Women, 33(4), 81–107.

[https://doi.org/10.14431/aw.2017.12.33.4.81]

-

Nam, S. W. (2019). A conceptualization of sexism in sport organizations. The Korean Journal of Physical Education, 58(2), 65–75.

[https://doi.org/10.23949/kjpe.2019.03.58.2.65]

-

Parihar, S. M., & Bannerjee, T. (2021). Women empowerment: Current insights and debates. International Journal of Social Science and Economics Invention, 7(1), 8–15.

[https://doi.org/10.23958/ijssei/vol07-i01/260]

-

Park, G. H., & Choi, Y. R. (2021). The study on the factors influencing regular employment, earned income and employment characteristics of female graduates in sports studies. Journal of Sport and Leisure Studies, 85, 321–334.

[https://doi.org/10.51979/KSSLS.2021.07.85.321]

-

Park, M. G., & Kim, Y. H. (2020). A study on the effect of the class ceiling on turnover intention of hotel employees: Focused on the moderating role of glass ceiling of other companies. Journal of Tourism Management Research, 24(7), 725–742.

[https://doi.org/10.9794/jspccs.29.316]

- Pennington, C. G. (2021). Concepts in occupational socialization theory. Curriculum and Teaching Methodology, 4(1), 1–3.

-

Richards, K. A. R., & Wilson, W. J. (2020). Recruitment and initial socialization into adapted physical education teacher education. European Physical Education Review, 26(1), 54–69.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X18825278]

-

Romar, J. E., & Frisk, A. (2017). The influence of occupational socialization on novice teachers’ practical knowledge, confidence and teaching in physical education. Qualitative Research in Education, 6(1), 86–116.

[https://doi.org/10.17583/qre.2017.2222]

Biographical Note: Jae Young Yang, Ph.D. is a visiting Professor in Sport Science of College, Sungkyunkwan University, South Korea. He received his Ph.D. from Texas A&M University, Kinesiology, College Station, TX. His research area focuses on teacher effectiveness, student motivation, and cognitive process in physical education as well as promotion for physical activity. E-mail: bestyang95@skku.edu