Unpacking the Standstill: What Drives the Stagnation of Women’s Labor Force Participation in Indonesia?

Abstract

Despite recent economic growth and meaningful improvements in women’s rights in Indonesia, gender gaps in labor force participation remain. To answer this question, we analyzed how Indonesians perceive gender equality as well as the factors that account for such perceptions of women’s rights. The results of a survey administered to 526 respondents in 2023 showed that skewed perceptions of social norms regarding gender roles may serve as the primary obstacle to achieving gender equality and account for the stagnation of women’s labor force participation in Indonesia. The religious commitments of Muslims and Hindus may also explain their varying levels of awareness and support for gender equality and women’s rights, potentially reconciling conflicting arguments regarding the role of Islam and religions in Indonesia. This study expands current research on gender disparity by highlighting the economic ramifications of gender norms.

Keywords:

Women’s Labor Force Participation, Indonesia, Gender Norms, Muslim, HinduismIntroduction

Indonesia’s economic growth has coincided with progress in women’s educational achievements and a decrease in the total fertility rate from 3.7 in 1980 to 2.2 in 2023 (World Bank, 2024). Progress has also been made regarding women’s rights. In 2019, Indonesia increased the minimum age at which women can marry from 16 to 19 years. In 2022, a Sexual Violence Bill was passed to protect women from sexual violence, including marital rape (Robinson, 2022). Furthermore, gender quotas have operated in district and provincial legislative elections since 2004 (Robinson, 2022), although women’s share of parliamentary seats in 2023 was approximately 21.6% (Statista, 2024).1

Despite this progress, women’s labor force participation rates in the formal sector have largely stagnated over the past two decades (Cameron, 2023). The participation rate was 51.6% in 2000 and has only marginally increased to 53.3% by 2023 (World Bank, 2024). According to the 2024 National Labor Force Survey (SAKERNAS) (BPS-Statistics Indonesia, 2024), the national Female Labor Force Participation Rate (FLFPR) in Indonesia stands at 55.4%, lower than that for men (84%).2 The female-to-male labor force participation rate stood at 61.4% in 2000 and increased to approximately 65% by 2023.3 According to data from 2023 (World Bank, 2024), 59.11% of individuals will be involved in informal work, which may involve self-employment, employers with temporary or unpaid assistance, casual labor, and unpaid family contributions. The data indicate that unpaid family workers constitute a significant part of the labor force, with a large percentage of these positions occupied by women. In contrast, 40.89% were engaged in formal employment, and 70.54% were men. Despite a rising trend towards wage employment, many Indonesian women continue to work in the informal sector as self-employed, casual, or unpaid family workers, holding jobs related to domestic work such as caregivers and nurses (Schaner & Das, 2016).

The proportion of voluntary, part-time female workers was 35.21%, which was significantly higher than the 17.48% rate of males. A wage gap persists between male and female workers, with women consistently earning less than men across all age groups and educational levels (BPS-Statistics Indonesia, 2024). Women’s earnings were approximately 59% of their male counterparts with the same level of education (a gap of 41%). A low share of earnings is a direct result of a low female labor rate.

The number of women engaged in agriculture has decreased over the past decade. Although agriculture continues to employ female workforce, the shift away from agriculture has led to a decline in women’s labor force participation, as many women who previously worked on family farms are less likely to remain employed when their families relocate to urban areas or lose access to agricultural land (Cameron, Suarez, & Rowell, 2019). In Indonesia, women frequently work in lower-productivity areas within the service industry, such as retail and hospitality. This concentration restricts opportunities for career growth and better pay. While the manufacturing sector employs fewer women than the service sector, there has been an increase in female involvement in this area. However, the increase in manufacturing jobs is more pronounced for men (BPS-Statistics Indonesia, 2024).

Moreover, there is a significant gender gap in high-ranking positions. The Global Gender Gap score, which measures gender disparity in education, health and survival, participation and economic opportunities, and political empowerment, ranked Indonesia 87th out of 146 countries in 2023 (World Economic Forum, 2023). Considering the recent advances in women’s higher education, declining early marriage rates, and low fertility, the stagnation of women’s participation and their weak economic empowerment are puzzling. Why are improvements for women in the key socioeconomic areas of health and education not effectively translated into gender equality in Indonesia’s labor market? Is this because efforts toward gender equality are nominal? (Aulia, 2024; Cameron, 2023; Locher-Scholten, 1999; White et al., 2023) Are there underlying factors that hinder the improvement of women’s labor force participation? While the existing literature is replete with studies focusing on the low level of female employment in Indonesia, the available evidence regarding the perceptive drivers of women’s participation and economic inequality deeply rooted in society is comparatively limited, and the perceptive factors hindering women’s involvement in the workforce and their unequal treatment remain largely understudied (Klasen, 2019). This lack of empirical evidence makes it difficult to address the dynamics that may drive or deter women’s economic participation and empowerment in Indonesia.

One reason for the stagnation of women’s economic participation in formal-sector jobs is that Indonesia has stagnant rates of female employment in the region. Existing research suggests that women holding wage jobs often have higher levels of income and empowerment (Cameron, 2023). For instance, employment may be linked to a decreased likelihood of experiencing spousal violence (Schaner & Das, 2016; Cameron, 2023). Women in wage jobs also tend to have greater influence on household decision-making processes (Majlesi, 2016). Therefore, this study presents a significant opportunity for policy initiatives to improve women’s engagement in the economy and thereby further empower women by investigating the perceptive factors potentially responsible for the stagnant female labor force participation rate in Indonesia.

A significant factor contributing to the stagnant female labor force participation rate in Indonesia may be the influence of prevailing gender norms on societal perceptions of women’s roles. These gender norms, which often confine women to limited and marginalized social roles, may hinder their participation in the workforce and devalue their contributions. The dual burden of work and family responsibilities can further exacerbate this issue, potentially driving women to exit the labor force.

Religious beliefs, particularly those rooted in Islam and Hinduism, along with deeply ingrained social institutions may also play a role in shaping public perceptions of women’s economic empowerment in Indonesia. While these religious and patriarchal social structures may negatively impact the recognition of women’s economic contributions, individuals actively involved in social or religious activities may be more exposed to gender equality issues and are more likely to hold positive views on women’s economic empowerment.

This study examines how gender norms, religions (Islam and Hinduism), and social institutions affect public perceptions of women’s rights and empowerment. While previous studies have indicated that Islam and religion may be correlated with gender-inequitable attitudes across countries (Lussier & Fish, 2016; Seguino, 2011; White et al., 2023), public opinion analyses of the link between religion and gender equality in Indonesia are lacking. In addition, we analyze how gender norms are associated with women’s rights perceptions. Using a survey experiment, we examined whether male or institutional leadership could play an important role in changing Indonesians’ support for women’s rights. In 2023, we surveyed 526 participants (mostly college students and faculty members from two Indonesian universities).4 The results show that, along with gender identity, social norms regarding gender roles in society and the religious activities of Muslims and Hindus are significantly associated with their perceptions of gender equality and women’s rights, potentially accounting for economic participation in Indonesia’s economy.

Background and Literature Review

Like many other countries in socioeconomic transition, gender equality remains a novel concept in Indonesia. While Indonesia has shown improvements in education and health, and moderate progress in women’s empowerment, performance in women’s labor force participation demonstrates that gender equality progress in Indonesia may be shallow (Aulia, 2024; Cameron, 2023; Locher-Scholten, 1999; White et al., 2023). Despite improvements in education and economic development, many women choose not to work or lack opportunities (Cameron, 2023).

Scholars have offered diverse explanations for variations in women’s economic participation. Previous studies have pointed out that Islam and religion may be associated with the stagnation of women’s access to employment (Inglehart & Norris, 2001; Robinson, 2022; Spierings, Smits, & Verloo, 2009). The rise of conservative religious agendas in Indonesian politics may restrict access to sexual health and reproductive services, and impose traditional morality on women. For example, the Gender Equality and Justice Bill to amend marriage laws, first proposed in 2010, faced significant delays. The legislation advocates equal pay for the same work, the right to decide on family planning, the freedom to choose a spouse without coercion, and fair treatment under the law. However, it has encountered opposition from Islamist groups, leading to parliamentary stagnation (Wijers, 2019). The 2019 Marriage Act also faced opposition from religious groups in defining adult-child marriages. Islamic rhetoric may also serve as a barrier to the advancement of women’s rights in other areas (Htun & Weldon, 2015; Robinson, 2022).

In Indonesia’s reform era, which followed Suharto’s departure in 1998, conservative Muslim factions promoted traditional interpretations of women’s roles. Despite initial rhetoric emphasizing women’s rights, there was a shift toward the concept of a “harmonious family,” where women were assigned subordinate positions. On the one hand, the harmonious family concept may have benefitted the women’s movement and had a significant influence on government policies. For example, the Ministry of Women’s Empowerment and Children’s Protection actively advocates for this, aiming to curb domestic violence. However, this concept may also have facilitated the resurgence of patriarchy in Indonesia (Wieringa, 2015).

It has also been argued that political Islam may be an empowering mechanism for gender equality that can strengthen women’s voices in the public sphere. Indonesia’s Islamic revival coincided with women’s growing involvement in civil society as an element of democratic opposition. The rise of the headscarf was perceived as a form of opposition to autocratic and secular regimes (Brenner, 1996). Muslim women have amplified their voices through activism focused on marriage law reform and addressing gender-based violence (Blackburn, 2008; Robinson, 2022). Islam’s increasing role may provide religious women with an important platform, facilitating their involvement in issues such as Shariah law, abortion, and pornography (Rinaldo, 2008).

Recent research has also described how women may use revisionist interpretations of Islam to press for gender equality (Kamla, 2019; Sirri, 2024). For example, in 2017, a women’s campaign supported by Nahdlatul Ulama, the largest Islamic organization, advocated for raising the minimum marriage age to 18 years and addressing sexual violence against women, regardless of marital status (Robinson, 2022). Islam may become a mobilizing ideology that enables Muslim women activists to be involved in the mainstream public sphere rather than being relegated to the feminist or Muslim public. In Indonesia, scholars have argued that middle-class women are likely to be attracted and mobilized to moderate Islam because of its modernizing aspects and that the expansion of moderate Islam has had tangible benefits for women (Blackburn, 2008) based on social movements across the political spectrum. Therefore, the Islamic revival and divergence between moderate and radical Islam may be a heterogeneous force contributing to or detracting from women’s rights in the public sphere (Blackburn, 2008).

Although Hinduism is a minority religion in Indonesia, it plays an important role in Indonesian society, particularly in Bali.5 Traditionally, Hinduism has identified the role of women as supporting the family and participating in its religious activities. Hindu women have been deprived of access to education and economic independence because of the prevailing belief that males should be the primary breadwinners (Agra, Gelgel, & Dharmika, 2018). However, in modern Hindu communities, women are encouraged to participate in economic activities. Many Hindu women have also raised their awareness of women’s rights. In particular, those who are politically or socially active are likely to recognize issues associated with women’s rights, such as resistance to an authoritarian government and discriminatory dress codes for women that apply to Hindus and other religious minorities (Human Rights Watch, 2021). Nevertheless, patriarchal norms still place Hindu women in socially subordinate positions, particularly in Balinese Hinduism in Indonesia. Women often face discrimination and are less likely to possess inherited rights (Segara, 2019).

Scholars have also argued that gender norms and social practices in Indonesia may affect the development of gender equality by constraining the probability of women’s employment. These norms may shape different aspects of gender dynamics, including economic participation, decision-making agency, and experiences of intimate partner violence or discrimination (Bussolo et al., 2024). In the pursuit of gender equality, invisible practices can underlie discriminatory social norms that dictate specific roles and power dynamics between men and women (Qanti, Peralta, & Zeng, 2022). Women’s roles can be limited by key life events such as educational achievements, age at marriage, and age at first childbirth, which may impact gender dynamics. However, gender norms may represent the main factors underlying decision-making regarding economic participation, fertility choices, and childbirth timing.

Women’s roles in Indonesia may also have been influenced by government policies during the New Order era (1966–1998). According to Blackburn (2004), the Suharto regime placed significant emphasis on reinforcing the gender hierarchy. This New Order ideology, which promotes traditional gender roles and highlights women’s importance as nurturers, continues to hold significant influence in various regions of Indonesia (Qanti, Peralta, & Zeng, 2022). In Indonesia, men are regarded as heads of the family and primary decision-makers (Puspitawati et al., 2018). Traditional gender roles assign women the primary responsibility for managing the household, including domestic tasks and childcare, while men are expected to serve as the family’s breadwinners (Puspitawati et al., 2018). Despite their active contributions, women’s roles are often perceived as secondary, merely existing to assist their husbands. Their contributions tend to be undervalued and can restrict their economic participation and involvement in decision-making, both within households and within the broader community (Wijers, 2019).

Gender norms counteracted the impact of policies designed to enhance women’s employment in several ways. For example, early and arranged marriage can prompt women to have children at a young age, further limiting women’s job prospects and constraining their employment opportunities (Delprato et al., 2015; Bussolo et al., 2024). In South Asia, women often face expectations to promptly start bearing children after marriage, particularly sons, to establish value (Javed & Mughal, 2019). Moreover, women may encounter a lack of access to childcare options (Bussolo et al., 2024).

Studies have recognized that social networks in both formal and informal institutions can influence diverse paths in the evolution of gender equality and gender-related outcomes. Social networks and bonds within a community shape women’s access to resources, economic opportunities, and decision-making power. For example, economic cooperatives can provide education and savings programs that support women’s financial autonomy, provide them with a support system, and expand market access beyond what they can reach as individual producers (Wijers, 2019). Social connections may act as empowerment mechanisms for women striving to enter and succeed in the labor market, including rural dwellings and lower-income women (Wijers, 2019).

However, social ties and networks can discourage empowerment. Social groups may promote traditional gender roles and limit women’s participation opportunities. Inequitable practices in both formal and informal institutions remain largely unchanged or have become more conservative, discouraging women from pursuing employment, joining the workforce, or taking on decision-making roles (Wijers, 2019), thus perpetuating patriarchal dominance and underrepresentation of women (Bjarnegård & Kenny, 2015). In addition, such practices may enforce conformity with established gender norms, making it challenging for women to break away from traditional expectations. Overall, the respondents’ perceptions of gender equality were influenced by religion, norms, and social networks.

Research Design

To evaluate whether perceptual factors are linked to low levels of women’s rights, we developed the following hypotheses based on a review of the literature. These hypotheses are not intended to directly assess the causal factors influencing the stagnation of women’s labor force participation at the individual level. Instead, this study examines how Indonesians perceive gender equality and whether distorted perceptions of social norms related to gender roles in society, religion, and social networks influence their views on women’s rights and empowerment. These factors may constitute the primary and systemic obstacles to achieving gender equality and explain the underlying reasons for the stagnation of women’s labor force participation in Indonesia.

Hypothesis 1a: Individuals who conform to gender norms are less likely to recognize the importance of gender equality in Indonesia.

Hypothesis 1b: Individuals who conform to gender norms are less likely to recognize discrimination against Indonesian women.

The first set of hypotheses assesses the influence of gender norms on Indonesians’ perceptions of the salience of gender equality and discrimination against women (Agra, Gelgel, & Dharmika, 2018; Puspitawati et al., 2018). Gender norms that define a restricted role for women may trap them in marginalized and precarious social roles, discourage women’s labor force participation, and/or undervalue their work. Those who conformed to the traditional Indonesian gender norms were less likely to perceive the importance of gender equality or discrimination against women.

Hypothesis 2: Muslims and Hindus who actively participate in religious gatherings are likely to recognize the importance of gender equality and discrimination against women in Indonesia.

The second hypothesis examines whether Muslim and Hindu religious activities are associated with Indonesians’ awareness of and recognition of gender inequality and discrimination against women. Social interactions enhanced by various religious groups such as the Indonesian Women’s Ulema Congress can promote activism regarding women’s rights (Rinaldo, 2008; Robinson, 2022), thereby increasing awareness of gender inequality and women’s rights. Therefore, while Islam and Hinduism may have a negative influence on perceptions of gender equality and women’s rights, those actively participating in religious gatherings may recognize the importance of women’s contributions to society; the existence of gender discrimination, such as sexual abuse or discriminatory dress codes imposed on women; and the salience of gender equality issues. In contrast, Muslims and Hindus who do not actively participate in religious meetings may be less likely to be exposed to political dialogue and social movements and thus less likely to recognize issues of gender equality and women’s rights.

Hypothesis 3: Those who are exposed to information about men’s support for women’s representation are more likely to support women’s representation than those who are exposed to information about women’s support.

Hypothesis 3 tests whether support for women’s political representation depends on whether the male or female leadership calls for support. Given that female leadership is comparatively rare in Indonesian society (Aspinall, White, & Savirani, 2021), we hypothesized that Indonesian people are likely to support women’s representation when they are exposed to information about men’s support rather than solely women’s support. In addition, such effects may be observed more distinctly among female respondents than male respondents.

Hypothesis 4: Those who are exposed to information about banjars’ support for government spending on women’s economic opportunities are more likely to support it than those who are only exposed to information about general support for such measures.

In the last hypothesis, we test whether people’s support for government spending on women’s economic opportunities is likely to increase when they are exposed to information about the banjars’6 support. Since the Banjars apply traditional laws and traditions that affect individual and family life, we argue that those who are aware of Banjars’ support for government spending on women’s economic opportunities may be likely to support such measures.

To test these hypotheses, we surveyed 526 participants from two universities in Indonesia in 2023.7 We targeted this demographic because our study aimed to explore attitudes toward gender equality and women’s economic opportunities. Typically, college students and university faculty have higher levels of education and a better understanding of gender equality than other societal groups. In the urban areas of Indonesia, younger women have increasingly joined the workforce through paid employment, while those in rural regions have stepped back from the labor force, often choosing to leave informal, unpaid roles (Shaner & Das, 2016). As a result, our participants were likely more attuned to and serious about gender equality. This also implies that they might hold favorable views on gender equality and perceive it as a societal issue rather than a personal one, potentially making the survey results more conservative than public perceptions of gender equality (Jo & Hwang, 2023).8

The survey asked various questions about the participants’ perceptions of gender norms, gender inequality, discrimination against women, and their support for women’s political representation and economic opportunities. Gender Equality and Discrimination Against Women were the dependent variables. Gender Equality was created based on the extent to which it was a serious issue that must be addressed in Indonesian society. Discrimination Against Women was based on how seriously respondents thought discrimination against women existed in society. Both variables have five ordered values (not very serious, not serious, neutral, somewhat serious, and very serious).

Gender norms exist in multifaceted ways (Hentschel, Heilman, & Peus, 2019). We used four questions to examine the impact of gender norms on perceptions of gender equality and discrimination against women. The first asked respondents about their perception of the comparative importance of marriage to a good man and a woman’s career success (Marriage Importance). The second asked whether they thought there were not many women with outstanding abilities compared to men in Indonesia (Women’s Ability). The third question asked whether it is natural for men to have a higher social status than women (Male Social Status). In the last question, we asked whether a married woman should take primary responsibility for housework even if she has a job (Housework). To test whether those who agreed with these statements were less likely to recognize the importance of gender equality or discrimination against women, we created a composite index of gender norms (Gender Norms) by combining four questions based on their high internal validity (Cronbach Alpha = .70). Based on these questions, the variables had five ordinal values (strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, and strongly agree). Gender Norms range from 0 (weakest conformity) to 16 (strongest conformity).

To test Hypothesis 2, we generated a series of variables based on the respondents’ self-identification with religion and their participation in religious gatherings. Active Muslim and Very Active Muslim are those who actively participate in religious gatherings. Muslim represents the remainder who do not actively participate in religious gatherings. The variables Active Hindu, Very Active Hindu, and Hindu were created in the same manner. Since one of the universities in the survey was located where most of the residents are Hindus, many respondents identified as Hindus (approximately 40%). These variables are all binary and coded as one for the designated group and zero otherwise.

To test Hypotheses 3 and 4, we conducted a survey. Women’s Representation and Women’s Economic Opportunities were the two proxy dependent variables in the experimental analyses. Women’s Representation was based on the extent to which respondents thought that the women’s representation rate in Indonesia’s National Assembly needed improvement. Women’s Economic Opportunities were created based on whether the respondents agreed that the government needed to allocate more financial resources to narrow the gender gap in economic opportunities. For both variables, the respondents were asked to choose a response from five ordered values (strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, and strongly agree) to express their level of support for the statement.

To examine how gender identity leadership or the Banjar affect people’s support for women’s political representation or government spending on women’s empowerment, we created two groups of respondents (one control group and another experimental group) and provided them with different sources of information. Experimental Group was the key explanatory variable and was coded as one for the experimental group and zero for the control group. For the experimental group, for one question, we provided the information that the female representation rate in the National Assembly was only 21% in 2021, and “some men” argued that the women’s representation rate in the National Assembly needs to be improved was provided to the group (Women’s Representation). For the control group, we provided the same information except that it was “some women” who make the argument. The purpose of this experiment was to assess the influence of male and female leadership on people’s support for women’s representation. To examine the dynamic interactions between the male group and the experiment, we created an interaction term between the experimental group and male variable.

In another question for the control group, we provided information that the COVID-19 pandemic has negatively affected the gender gap and that some claimed that the government needs to allocate more financial resources to narrow the gender gap in Economic Opportunities, while others argued otherwise (Women’s Economic Opportunities). For the experimental group, we provided the same information except that it was “some leaders in the Banjar” who were making the claim. The purpose of this experiment is to evaluate the influence of Banjar institutional leadership on people’s support for government spending on women’s economic opportunities.

We also include control variables. The Male variable was coded as one if the respondent was male, and zero otherwise. Education was coded as one for elementary school, two for middle school, three for high school, four for two-year college, five for four-year college (currently enrolled), six for four-year college (graduated), and seven for graduate school as the highest level of education. Socioeconomic Status was coded as one for the lower class, two for the lower-middle class, three for the middle class, four for the middle-upper class, and five for the upper class. It is difficult to predict how such variables might impact perceptions of gender equality and women’s rights. Those with high levels of education or socioeconomic status may appreciate gender issues more than others do. However, due to their relatively high satisfaction with their socioeconomic status, they may have underappreciated the existence of these issues. Those living in big cities may perceive gender-related issues seriously and hold different gender norms than those living in towns or rural areas. The City variable was coded as one for those who lived in rural areas, two for towns and small cities, and three for large cities.

Those affiliated with Banjars may maintain distinct gender norms and perceptions of women’s rights differently than others. However, we had no clear expectation of the Banjars’ impact on people’s support for women’s rights. On the one hand, as the keeper of religious and cultural traditions in the community, a banjar may promote male-centric norms and culture, giving little consideration to gender equality or women’s rights. On the other hand, as active local communities, banjars have been utilized by women to support and develop their economic activities and networks (Indriani & Widnyana, 2019). For example, Pemberdayaan Kesejahteraan Keluarga (the Family Welfare Empowerment Movement), a women’s organization at the grassroots level, holds monthly meetings in Banjar and supports social activities that may foster community welfare development and maternal or childhood health programs (Aspinall, White, & Savirani, 2021; Marcoes, 2002). Banjar is coded as one if it does not exist in the respondent’s area, two if it exists but seldom affects the respondent’s life, and three to six depending on whether it affects the respondent’s life a little, to some extent, a lot, or very significantly. Because the dependent variables had ordinal values, we utilized ordered logit models with robust standard errors.9 The descriptive statistics are presented in Table A1 in the Appendix.

Results

Table 1 reports the results of the links between gender norms, religious commitment, and perceptions of gender equality and discrimination against women. In all the models, the Male variable appeared to have significant negative effects on perceptions. To evaluate the substantive effects of the covariates on the dependent variables, we utilized the Clarify program for simulation (Tomz, Wittenberg, & King, 2003). Male respondents, as compared to female respondents, tended to underappreciate the importance of gender equality or the existence of discrimination against women in Indonesia. For instance, holding the other variables at their means in Model 2, the predicted probability of a very active male Muslim respondent agreeing or strongly agreeing with the importance of gender equality was 48%,10 whereas it was 71% for a very active female Muslim respondent. Similarly, holding the other variables at their means in Model 4, the predicted probability of a very active male Muslim respondent agreeing or strongly agreeing with the existence of discrimination against women was 32%, whereas it was 50% for a very active female Muslim respondent.

The perception of gender norms appeared to have a strong effect on the respondents’ awareness of gender equality and discrimination against women. Those conforming to patriarchal gender norms tend to have a lower awareness of gender equality and discrimination against women. For instance, the predicted probability that a very active Muslim respondent who weakly conformed (10 percentile value of the index variable) to gender norms agreed or strongly agreed with the importance of gender equality was 45% (men) and 68% (women), respectively, whereas it decreased to 27% (men) and 49% (women) for a very active Muslim respondent who strongly conformed (90 percentile value of the variable) to patriarchal gender norms.

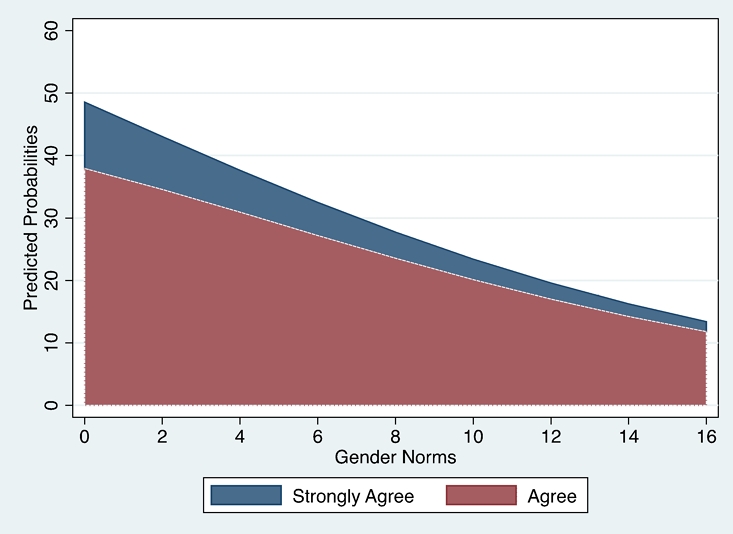

To illustrate the predicted probabilities over the range of gender–norm conformity, we generated Figure 1, based on Model 2. The predicted probability that a very active male Muslim respondent agrees or strongly agrees with the importance of gender equality varies from 49% to 13%, depending on their conformity to patriarchal gender norms.

Gender norms have substantively significant effects on Indonesians’ perceptions of gender equality. Similarly, the predicted probability that very active Muslim respondents who weakly conformed to gender norms agreed or strongly agreed with the existence of discrimination against women was 67% (men) and 82% (women), respectively, whereas it decreased to 42% (men) and 61% (women) for very active Muslim respondents who strongly conformed to gender norms.

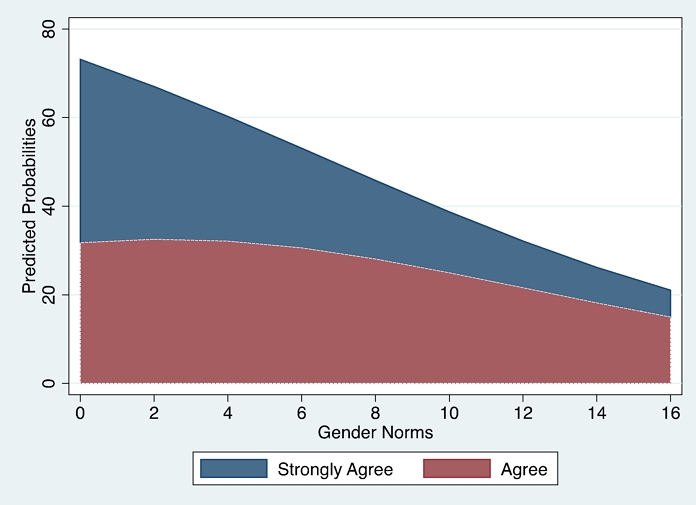

To illustrate the predicted probabilities over the range of gender norm conformity, Figure 2 was generated using Model 4. As the figure shows, the predicted probability that a very active male Muslim respondent agrees or strongly agrees with the existence of discrimination against women varies from 73% to 21% depending on their conformity to gender norms. Significant substantive changes in the predicted probabilities demonstrate that gender norms play a crucial role in Indonesians’ perceptions of discrimination against women. These results show that deep-rooted perceptual gender norms and patriarchal values may serve as significant obstacles to women’s economic empowerment to some extent (Aspinall, White, & Savirani, 2021).

Regarding Hypothesis 2, we failed to find statistically significant results in Model 2. Regardless of their participation in religious gatherings, Muslims did not show statistically significant differences from the other groups in their perceptions of gender equality. However, the insignificant results may imply that Muslims do not necessarily discount the importance of gender equality compared to others, rejecting the conventional belief that Islam plays a negative role with respect to gender equality. Our empirical results show that Islamic religious identification may not be a pivotal force that detracts from perceptions of women’s rights. These findings are important, especially given that some recent articles contend that Islamic self-identification tends to marginalize gender equality (Lussier & Fish, 2016). Unlike these studies, we empirically demonstrate that Islamic religious commitment does not necessarily cause Indonesian conservative bystanders to discriminate against women.

In Model 4, Hindus tended to undervalue the importance of discrimination against women compared to others, confirming the conventional belief that Hinduism may play a negative role in Indonesia with respect to gender equality. However, as Hindus become more active at religious gatherings, these negative effects disappear. Hindus who were very active in religious gatherings tended to underestimate discrimination against women more than others, but the negative impact was not statistically significant. These findings do not offer empirical support for Hypothesis 2. However, as very active Hindus are not statistically different from other groups in their recognition of the importance of discrimination against women, these results challenge the conventional belief that Hinduism acts as a perceptual barrier to the advancement of women’s rights in Indonesian society.

With respect to Hypothesis 3, we found that the experimental group showed statistically significant positive support for women’s representation (Table 2). In other words, people who are exposed to information about men’s support for women’s political representation (here, the experimental group) are more likely to support it than people who are exposed to the same information, but where the support is female. In Model 5, support for women’s representation in the experimental group (male support) was 54% (Islamic males) and 72% (Islamic females), compared with 46% and 54%, respectively, in the control group (female support). This implies that the influence of women’s leadership in Indonesia may still be weak, and that men could play a significant role in promoting gender equality and women’s political representation. These results provide potential insights, although they should be interpreted with caution as our survey was neither extensive nor randomized. At the very least, our findings emphasize the necessity for additional research on this topic.

As the results in Model 6 show, the influence of the experiment on support for women’s representation was contingent on the respondents’ gender. In other words, female respondents were more likely than male respondents to support leadership in the experimental group, implying that female respondents are more sensitive to gender identity in leadership. Gender norms and religion appear to have significant effects on support for women’s representation. Those who conform to gender norms tend not to support women’s representation.

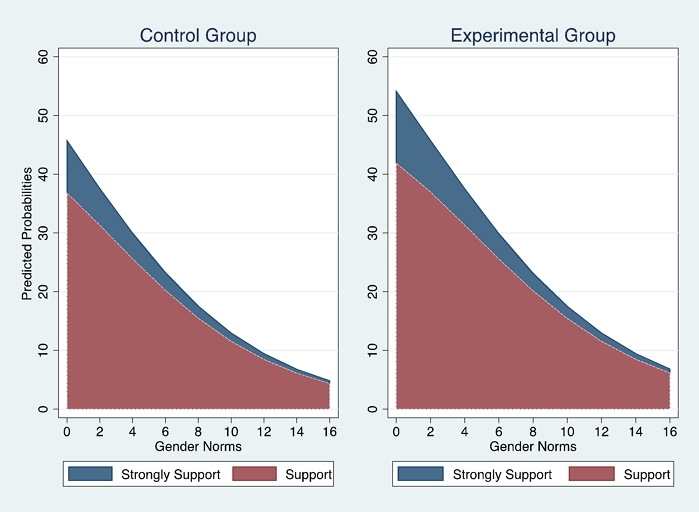

To illustrate the predicted probabilities over the range of gender norm conformity for both the control and experimental groups, Figure 3 was generated using Model 5. As the figure shows, the predicted probabilities that a very active Muslim male respondent supports or strongly supports women’s representation vary from 46% to 4.9% for the control group and from 54% to 6.9% for the experimental group, depending on their conformity to gender norms. Clearly, perceptive norms regarding gender roles have substantively significant effects on the respondents’ support for women’s representation. It also suggests that implementing a quota system alone may not effectively address the structural disadvantages that women encounter in political representation (Aspinall, White, & Savirani, 2021).

When a politically sensitive question about women’s political representation was posed to respondents, we found that Hindus who did not actively participate in religious gatherings were unlikely to support them. Even active Muslims tend not to support women’s political representation. However, very active Muslims and Hindus did not show statistically significant differences from the other groups in this regard. Meanwhile, the Banjar appears to have a positive influence on people’s support for women’s representation. People who are strongly affiliated with Banjars are more likely to support women’s representation (+7% men and +11% women) than those who are not affiliated with the Banjars.

In the second experiment, we tested the influence of banjars on people’s support for government spending on women’s economic opportunities. However, we found no significant differences between the results. This result may imply that Indonesian people may not have a favorable attitude toward government spending on women’s economic opportunities or that the Banjar may not have a significant influence on people’s perceptions of government spending on women’s economic opportunities.

Gender norms also failed to generate statistically significant effects on support for government spending on women’s opportunities. This result may imply that with respect to government spending on women’s economic opportunities, respondents’ perceptions of the policy are relatively firm, regardless of their conformity to gender norms, potentially accounting for women’s low economic rights. As Table A1 shows, the average support for government spending on women’s economic opportunities was lower than that for other issues such as women’s political representation or discrimination against women.

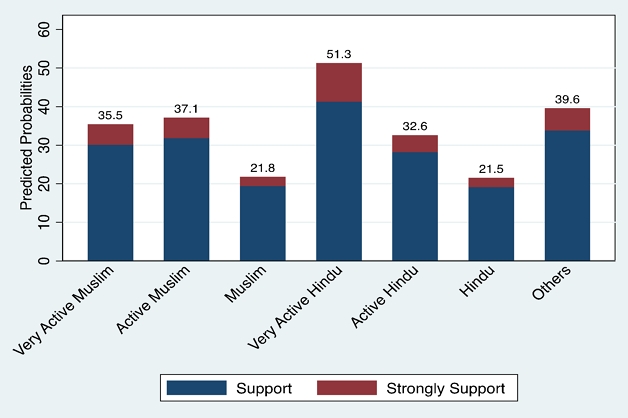

Regarding the impact of religious activities on support for government spending on women’s economic opportunities, Muslims and Hindus who do not actively participate in religious gatherings are unlikely to support them, as expected, while those who actively participate in religious gatherings do not show statistically significant differences from others in their support. To examine the predicted probabilities of support for government spending on women’s economic opportunities across the different activity groups of Muslims and Hindus, we generated Figure 4 based on Model 7. While the predicted probabilities that an active or very active Muslim male supports or strongly supports such spending are 37% and 36%, respectively, the probability that a Muslim male who does not actively participate in religious gatherings supports or strongly supports spending is only 22%. Similarly, the predicted probabilities that an active or very active Hindu male supports or strongly supports such spending are 51% and 33%, respectively, whereas the probability that a Hindu male who does not actively attend religious gatherings supports or strongly supports spending is only 22%. Considering that the predicted probability for others who are not Muslims or Hindus is 40%, Muslims or Hindus who are not actively involved in religious gatherings show relatively low support for government spending on women’s economic opportunities. Depending on their religious activities and commitments, Muslims and Hindus may experience significant discrepancies in their perceptions of gender equality and women’s economic rights.

Religious activities and support for government spending on women’s economic opportunities (a male respondent)

Meanwhile, those with high socioeconomic status are likely to support government spending on women’s economic opportunities. In all the models in Table 2, the gender variable appears to be a strong factor accounting for differences in people’s support for women’s rights. Male respondents were less likely than female respondents to support women’s representation or government spending on women’s economic opportunities.

Overall, our findings suggest that the stagnation of women’s labor force participation in Indonesia is deeply rooted in entrenched gender norms and patriarchal values, which continue to pose significant barriers to women’s economic empowerment. These societal norms advance women’s participation in the workforce and address gender disparities in economic opportunities, a particularly challenging and protracted endeavor. The pronounced disparity between male and female respondents in their perceptions of the importance of women’s rights and economic empowerment further complicates the progress. Alarmingly, this study shows that women’s leadership has a surprisingly weak impact on public perceptions of women’s rights, even among female respondents, compared with male leadership. This paradox underscores the reality that the stagnation in women’s labor force participation is not merely a consequence of public views on women’s economic roles but is also deeply influenced by ingrained societal perceptions of women’s places in both the public and private spheres. These findings suggest that meaningful progress will require more than just policy changes; it will also require a fundamental shift in societal attitudes towards gender roles.

Meanwhile, the empirical results revealed a nuanced relationship between religious identification, particularly within Islam, and gender equality. Contrary to previous studies emphasizing the negative impact of Islamic religious identification on gender equality (Lussier & Fish, 2016), our findings suggest a more complex dynamic. Specifically, religious commitment and participation in religious or social activities may help mitigate these negative effects and foster progressive perceptions of women’s rights in Indonesian society. This insight not only offers a potential reconciliation between conflicting research on the roles of Islam and Hinduism in relation to women’s rights and economic empowerment in Indonesia but also challenges the simplistic narrative that links religious identification to gender inequality. By highlighting the transformative potential of active engagement in religious practices and community activities, our findings highlight the possibility of harnessing religious engagement to advance gender equality in traditionally conservative contexts.

Conclusions

In Indonesia, gender equality and women’s rights are complex and multifaceted issues. Despite Indonesia’s recent economic growth and significant progress in women’s rights, particularly in education and health, gender gaps in labor force participation remain stagnant. This study suggests that the public perception of gender equality and women’s rights may be related to a lack of progress in women’s rights in economic areas (Jo & Hwang, 2023). To determine the factors that account for the public’s perceptions of gender equality and women’s rights, we explored the impacts of gender norms, religion, and social institutions. Overall, the findings show that Indonesians’ perceptions of gender equality and women’s rights are significantly influenced by patriarchal social norms. This highlights the structural weaknesses that disadvantage Indonesian women in terms of economic participation, through attitudinal impediments to their gender roles.

Gender norms emphasizing patriarchal culture, male dominance, and women’s traditional domestic roles may create visible and invisible stumbling blocks to women’s economic participation. Religious traditions and cultures may also reinforce prejudice against women’s economic participation. However, the relationship between Islam and Hinduism and Indonesian people’s perceptions of gender equality and women’s rights is complex and multifaceted, and depends on the level of religious commitment. While religious identification may limit perceptions of gender equality, different levels of commitment to Islamic networks and Hinduism may serve as opportunities to change public perceptions of gender equality and women’s rights.

The experimental results reveal a striking reality: survey participants, especially women, responded more positively to male leadership than to female leadership when it came to endorsing women’s representation. This finding highlights the pivotal and influential role of male support in shaping societal attitudes in Indonesia. As male support has been shown to be influential, engaging men as allies in gender equality efforts is essential. Programs that educate and involve men in gender equality initiatives can help shift perceptions and create a supportive environment for women’s rights. However, the evidence that male respondents tend to show very divergent views on gender equality and women’s rights from female respondents in the survey indicates that gender-based social cleavages are deeply rooted in society.

Our findings reveal deeply entrenched persistent gender biases, where even the advancement of women’s rights is often dependent on male advocacy. This paradox not only underscores the significant hurdles women face in achieving gender equality but also highlights the urgent need to challenge and reshape societal perceptions that continue to marginalize women’s voices and leadership. Without confronting these underlying biases, efforts to advance gender equality may remain superficial, failing to dismantle the barriers to women’s representation and labor market participation in Indonesia. Implementing systematic changes will require sustained efforts from all levels of society, including the government, civil society, educational institutions, and individuals to create a more equitable environment in which women’s empowerment and leadership are recognized and valued.

The findings also reveal encouraging signs, suggesting a potential path toward achieving gender equality and advancing women’s rights. As the Indonesian economy grows, people with a higher socioeconomic status are more likely to recognize the importance of women’s economic opportunities. Banjars, women’s organizations, and religious institutions in Indonesia can serve as powerful catalysts for promoting women’s social and economic participation, thereby significantly enhancing awareness and perceptions of gender equality and women’s empowerment (Marcoes, 2002; Rinaldo, 2008). Notably, individuals who do not engage in such meetings and activities often hold negative views on gender-related issues, whereas those who actively participate in social activities, regardless of their religion, tend to adopt more progressive views of gender equality. These findings are crucial, as they challenge the conventional wisdom that religious institutions inherently oppose women’s rights. Instead, they revealed that religious and community engagement can play a transformative role in advancing gender equality. This has the potential to reconcile longstanding debates on the influence of Islam and other religions on women’s rights in Indonesia, highlighting the potential of religious and social institutions as drivers of gender equality.

In response to the question about the most significant factor that accounts for women’s low labor force participation, most survey respondents (63.4% of female participants, 50% of males) chose “cultural traditions or practices that prevent women’s labor participation” and “lack of social programs that support women’s labor participation” as the two most important factors. Only a small proportion (6% of female participants, 7.4% of male) choose “women’s lack of skills” and “women’s lack of interest in economic activities.” This indicates that most respondents understand that women’s low labor force participation is driven mostly by social norms or a lack of support programs, rather than personal reasons. This suggests that implementing gender equality campaigns, targeted interventions to change social norms restricting women’s economic participation, and comprehensive social programs supporting women can greatly enhance women’s economic empowerment in Indonesia.

Given that the participants were mostly students and faculty members who were more likely to have positive views on gender equality and women’s rights than other groups, the negative effects of gender norms and gender identity on the public perception of women’s rights may be more serious in Indonesian society. These results highlight the obstacles Indonesia faces on its path toward gender equality and women’s economic empowerment. However, the empirical results have limited generalizability, even within Indonesia, because the survey targets were restricted to specific groups of university students and faculty members. As a well-educated group with greater awareness of gender equality compared to other segments of society, their responses to questions may have been biased toward supporting gender equality. In addition, although significant efforts were made to ensure anonymity and confidentiality in the survey, social desirability bias may have influenced responses. Future studies should broaden the scope of participation beyond college students and faculty members for a more comprehensive understanding of the relationships between gender norms, religion, and perceptions of gender equality across different segments of society.

Acknowledgments

This research was done as a part of the 2023 UNESCO UNITWIN project at Sookmyung Women’s University.

Notes

References

-

Agra, I. B., Gelgel, I. P., & Dharmika, I. B. (2018). Pressure on socio-cultural towards post-divorce Hindu women in Denpasar city. International Journal of Social Sciences Humanities, 2(3), 63–78.

[https://doi.org/10.29332/ijssh.v2n3.191]

-

Aspinall, E., White, S., & Savirani, A. (2021). Women’s political representation in Indonesia: Who wins and how? Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 40(1), 3–27.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/1868103421989720]

- Aulia, B. (2024). Indonesia: “Ring the Bell for Gender Equality” calls for investment in women’s economic empowerment. Retrieved May 28, 2024, from https://asiapacific.unwomen.org/en/stories/feature-story/2024/05/indonesia-rtb-calls-for-investment-in-womens-economic-empowerment

-

Bjarnegård, E., & Kenny, M. (2015). Revealing the “secret garden”: The informal dimensions of political recruitment. Politics & Gender, 11(4), 748–753.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X15000471]

-

Blackburn, S. (2004). Women and the state in Modern Indonesia. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511492198]

-

Blackburn, S. (2008). Indonesian women and political Islam. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 39(1), 83–105.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022463408000040]

- BPS-Statistics Indonesia. (2024). Labor Force Situation in Indonesia, 46(1). https://www.bps.go.id/en/publication/2024/06/07/112a10c79b8cfa70eec9f6f3/labor-force-situation-in-indonesia-february-2024.html

-

Brenner, S. (1996). Reconstructing self and society: Javanese Muslim women and “the Veil.” American Ethnologist, 23(4), 673–97.

[https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.1996.23.4.02a00010]

-

Bussolo, M., Ezebuihe, J. A., Munoz Boudet, A., Poupakis, S., Rahman, T., & Sarma, N. (2024). Social norms and gender disparities with a focus on female labor force participation in South Asia. The World Bank Research Observer, 39(1), 124–158.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkad010]

-

Cameron, L. (2023). Gender equality and development: Indonesia in a global context. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 59(2), 179–207.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2023.2229476]

-

Cameron, L., Suarez, D. C., & Rowell, W. (2019). Female labor force participation in Indonesia: Why has it stalled? Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 55(2), 157–192.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2018.1530727]

-

Delprato, M., Akyeampong, K., Sabates, R., & Hernandez-Fernandez, J. (2015). On the impact of early marriage on schooling outcomes in Sub-Saharan Africa and South West Asia. International Journal of Educational Development, 44, 42–55.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2015.06.001]

-

Hentschel, T., Heilman, M. E., & Peus, C. V. (2019). The multiple dimensions of gender stereotypes: A current look at men’s and women’s characterizations of others and themselves. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(11), 1–19.

[https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00011]

-

Htun, M., & Weldon, L. (2015). Religious power, the State, women’s rights, and family law. Politics & Gender, 11(3), 451–477.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X15000239]

- Human Rights Watch. (2021, March 18). Indonesia: Dress codes discriminate against women, girls. Retrieved November 29, 2024, from https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/03/18/indonesia-dress-codes-discriminate-against-women-girls

- Indriani, M. N., & Widnyana, I. N. S. (2019). Banjar Adat as ‘a place’ in the self-actualization of Bali women. GAP GYAN, 2(2), 40–51.

-

Inglehart, R., & Norris, P. (2001). Women and Democracy: Cultural Obstacles to Equal Representation. Journal of Democracy, 12(3), 126–140.

[https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2001.0054]

-

Javed, R., & Mughal, M. (2019). Have a son, gain a voice: Son preference and female participation in household decision making. Journal of Development Studies, 55(12), 2526–2548.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2018.1516871]

-

Jo, J., & Hwang, W. (2023). Deceptive gender equality: Unlocking the “black box” of Lao people’s perception of gender equality. Asian Survey, 63(6), 980–1001.

[https://doi.org/10.1525/as.2023.2075854]

-

Kamla, R. (2019). Religion-based resistance strategies, politics of authenticity and professional women accountants. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 59, 52–69.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2018.05.003]

-

Klasen, S. (2019). What explains uneven female labor force participation levels and trends in developing countries? World Bank Research Observer, 34(2), 161–197.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkz005]

-

Locher-Scholten, E. (1999). The colonial heritage of human rights in Indonesia: The case of the vote for women, 1916-41. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 30(1), 54–73.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/S002246340000802X]

-

Lussier, D. N., & Fish, M. S. (2016). Men, Muslims, and attitudes toward gender inequality. Politics and Religion, 9(1), 29–60.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048315000826]

-

Majlesi, K. (2016). Labor market opportunities and women’s decision-making power within households. Journal of Development Economics, 119, 34–47.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2015.10.002]

-

Marcoes, L. (2002). Women’s grassroots movements in Indonesia: A case study of the PKK and Islamic women’s organizations. In K. Robinson & S. Bessell (eds.), Women in Indonesia: Gender, Equity and Development (pp. 187–197). Singapore: ISEAS Publishing.

[https://doi.org/10.1355/9789812305152-022]

-

Puspitawati, H., Faulkner, P. E., Sarma, M., & Herawati, T. (2018). Gender relations and subjective family well-being among farmer’s families: A comparative study between uplands and lowlands areas in West Java Province, Indonesia. Journal of Family Sciences, 3(1), 53–74.

[https://doi.org/10.29244/jfs.3.1.53-72]

-

Qanti, S. R., Peralta, A., & Zeng, D. (2022). Social norms and perceptions drive women’s participation in agricultural decisions in West Java, Indonesia. Agriculture and Human Values, 39(2), 645–662.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-021-10277-z]

-

Rinaldo, R. (2008). Envisioning the nation: Women activists, religion and the public sphere in Indonesia. Social Forces, 86(4), 1781–1804.

[https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.0.0043]

- Robinson, K. (2022). Empowering women’s rights in Indonesia. East Asia Forum Quarterly, 14(4), 21-25. Retrieved November 29, 2024, from https://eastasiaforum.org/quarterly/

-

Schaner, S., & Das, S. (2016). Female labor force participation in Asia: Indonesia country study. Asian Development Bank Economics Working Paper Series No. 474.

[https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2737842]

-

Segara, I. N. Y. (2019). Balinese Hindu women. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, 339, 170–174.

[https://doi.org/10.2991/aicosh-19.2019.38]

-

Seguino, S. (2011). Help or hindrance? Religion’s impact on gender inequality in attitudes and outcomes. World Development, 39(8), 1308–1321.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.12.004]

-

Sirri, L. (2024). From theory to action: A Saudi Arabian case study of feminist academic activism against State oppression. Societies, 14(3), 1–15.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/soc14030031]

-

Spierings, N., Smits, J., & Verloo, M. (2009). On the compatibility of Islam and gender equality. Social Indicators Research, 90(3), 503–522.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-008-9274-z]

- Statista. (2024). Proportion of seats held by women in national parliaments in Indonesia from 2014 to 2023. Retrieved August 13, 2024, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/730286/indonesia-proportion-of-seats-held-by-women-in-national-parliament/

-

Tomz, M., Wittenberg, J., & King, G. (2003). Clarify: Software for interpreting and presenting statistical results. Journal of Statistical Software, 8(1), 1–30.

[https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v008.i01]

-

Wade, J. C., Suryani, L. K., & Lesmana, C. B. J. (2018). Religiosity, masculinity, and marital and life satisfaction among Balinese Hindu men. International Journal of Research Studies in Psychology, 7(1), 99–114.

[https://doi.org/10.5861/ijrsp.2018.3006]

-

White, S., Warburton, E., Pramashavira, H.A., Aspinall, E. (2023). Voting against women: Political patriarchy, Islam, and representation in Indonesia. Politics & Gender, 20(2), 391–421.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X23000648]

-

Wieringa, S. E. (2015). Gender harmony and the happy family: Islam, gender and sexuality in post-Reformasi Indonesia. South East Asia Research, 23(1), 27–44.

[https://doi.org/10.5367/sear.2015.0244]

-

Wijers, G. D. M. (2019). Inequality regimes in Indonesian dairy cooperatives: Understanding institutional barriers to gender equality. Agriculture and Human Values, 36, 167–181.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-018-09908-9]

- Williams, R. (2005). Gologit2: A program for generalized logistic regression/partial proportional odds models for ordinal variables. Retrieved March 1, 2024, from http://www/nd.edu/~rwilliam/stata/glogit2.pdf

- World Bank. (2024). World Bank Open Data. Retrieved August 14, 2024, from https://data.worldbank.org/

- World Economic Forum. (2023). Global Gender Gap Report. Retrieved November 29. 2024, from http://reports.weforum.org/globalgender-gap-report-2023

Appendix

Biographical Note: Wonjae Hwang is a Professor in the department of political science at the University of Tennessee. His research focuses on the link between economic globalization and domestic/international politics. He has published a book and numerous journal articles in some of the best outlets in political science and Asian studies including American Journal of Political Science, Journal of Politics, International Studies Quarterly, and Asian Survey. E-mail: whwang@utk.edu

Biographical Note: Jung In Jo is a Professor of the Division of Global Cooperation, School of Global Service, at Sookmyung Women’s University, Seoul, Republic of Korea. She holds a Ph.D. in International Relations from Michigan State University. Her research focuses on the link between economic globalization and domestic politics. She has numerous journal articles including Violence against Women, Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, and Asian Survey. E-mail: junginc@sookmyung.ac.kr