Violence Against Women in the Philippines Based on the Ecological Framework

Abstract

This article uses an ecological framework to look at violence against women in the Philippines. The serious global issue of violence against women has an influence on women's physical and mental health as well as human rights. Violence against women still occurs in the Philippines despite legislative attempts, such as the anti-violence law against women and children. This research aims to analyze the prevalence and characteristics of violence against women within Heise’s ecological framework by considering individual, situational, and social factors. The research utilizes qualitative methods, including the analysis of secondary data from government reports, international organizations, and academic literature, to gain a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing gender-based violence in the Philippines. The findings indicate that situational factors, especially male dominance in family relationships, are the most substantial contributors to high levels of violence against women, followed by individual and societal factors.

Keywords:

Violence, Women, Philippines, Ecological FrameworkIntroduction

Violence against women is a global scourge that seriously jeopardizes human rights and public health, not just a local problem. Violence against women is categorically defined by the World Health Organization (2013) as a public health emergency and a flagrant violation of women’s fundamental rights. Abuse can be physical, sexual, emotional, or financial, among other forms of violence. Women’s physical and emotional health suffer greatly from each of these manifestations. The gravity of this situation cannot be overstated, as it leads to injuries, chronic physical ailments, mental health disorders like depression and anxiety, and, in the most extreme cases, death. Moreover, the pervasive nature of violence against women obstructs the path to gender equality, as it perpetuates gender-based power imbalances and societal norms that condone discrimination against women (Okenwa-Emgwa & von Strauss, 2018).

The impact of violence against women extends beyond individual suffering, as it also hampers economic progress by curtailing women's access to resources and education. UN Women (2020) underscores the necessity of comprehending the cultural, social, and economic ramifications of violence against women to combat it effectively. To this end, a comprehensive approach is indispensable. Such an approach not only protects women’s rights but also contributes to the creation of a just and sustainable society (Stalans & Lurigio, 1995).

Violence against women is a pervasive problem that plagues countries worldwide, yet its forms and origins can vary significantly across cultures and societies. In the Philippines, despite numerous legislative efforts to promote gender equality, violence against women remains deeply entrenched in cultural norms and societal structures. Society often downplays the severity of violence against women, leading to a significant number of cases going unreported. Shockingly, around 25% of Filipino women aged 15-49 years have experienced physical, sexual, or emotional violence from a partner at some point in their lives (Vizcarra et al., 2004). Furthermore, the PSA (Philippine Statistics Authority) reports that only about 30% of women who experience sexual violence from their partners seek help or report the incident. This culture of silence and tolerance exacerbates the problem, rendering it a challenge despite legal protections (Philippine Statistics Authority, 2018).

Based on the theory and background explained the research focuses on research questions regarding how violence against women in the Philippines is based on ecological framework analysis. The hypothesis that emerges is that violence against women in the Philippines is based on an ecological framework due to male dominance in the family sphere.

Literature Review

This research uses literature studies from various sources, significant journal articles, or previously published research relating to acts of violence against women in the Philippines. The frequency and types of violence against women in the Philippines have been extensively studied these include, but are not limited to physical, sexual, psychological, and economic abuse. One of the studies conducted by Shoultz et al. (2010) highlighted the widespread nature of intimate partner violence in the country. Their findings show that cultural norms and traditional gender roles contribute significantly to the normalization of violence against women. Likewise. Antai & Anthony (2014) emphasize the role of social attitudes in perpetuating violence. These factors collectively create an environment where violence against women is widespread and often goes unreported.

Yoon and Bor (2020) wrote that cultural norms and societal values in the Philippines perpetuate gender-based violence by emphasizing the need for cultural change along with legal reform. This finding suggests that interventions should not only focus on changing laws but also on shifting societal attitudes. Antai & Anthony (2014) conducted comprehensive research linking violence against women with physical and mental health impacts. Their study revealed that women who experience violence are more likely to suffer from depression, anxiety, and other health problems. This underscores the need for comprehensive support services for survivors of violence, including mental health care.

Family influence factors a term used to describe the various ways in which family dynamics and structures can contribute to violence against women, have been studied by Serquina-Ramiro, Madrid, and Amarillo (2004), they found that women in households with a rigid patriarchal structure were more likely to experience domestic violence. They argue that power imbalances within the family unit, reinforced by social norms, often leave women vulnerable to abuse. This opinion is also in line with research conducted by Mandal & Hindin (2015) which found that family expectations and pressure can exacerbate incidents of violence, especially in large family environments, which are common in the Philippines. Not only that, Widom & Wilson’s (2014) research highlights the passing of violence from generation to generation. They discovered that kids who grew up with exposure to domestic abuse were more likely to engage in violent relationships themselves or become victims of it. The cyclical nature of violence underscores the importance of addressing family dynamics in any intervention strategy. However, this research is not based on an ecological framework that discusses the problem of women's violence in the Philippines more comprehensively, not just family factors that are the cause.

Meanwhile, research addressing the gap between men and women was written by Tsai, (2017) which explains how economic pressure and dependence on male partners can increase women's vulnerability to violence. Women who lack economic independence are often trapped in abusive relationships due to financial constraints and limited opportunities to escape. Research conducted by McDoom et al. (2019) tested the correlation between economic inequality and family violence. These findings indicate that economically disadvantaged women are more likely to experience violence due to increased stress and conflict due to limited resources. This research is supported by research by Dalal (2011) which found that women’s economic empowerment through education and employment can significantly reduce the incidence of domestic violence by changing the power dynamics in the household.

Most of the literature discussed above has highlighted the various factors that cause violence against women in the Philippines and emphasized the link between family dynamics and economic inequality. However, there has been no research providing an overview of how violence against women occurs in the Philippines by contextualizing the findings in the ecological framework proposed by Heise (1998). Heise’s ecological analysis, which will be introduced later in this review, contributes to providing solutions to resolving the problem of women's violence in the Philippines once the causes are known.

Theoretical Framework

The theory in this research comes from Heise’s (1998) ecological theory, which advocates a comprehensive approach to understanding the origins of gender-based violence. According to this theoretical framework, violence is seen as a multifaceted phenomenon that arises from interactions between personal, situational, and socio-cultural factors. This framework emphasizes the complexity of violence and the need to consider multiple levels of influence in its etiology.

The proposed theoretical framework adopts an ecological perspective to conceptualize the etiology of gender-based violence. This framework recognizes the interaction between personal, situational, and socio-cultural factors and emphasizes the need for a comprehensive and integrated approach to building theory. By synthesizing findings from multiple disciplines and cultural contexts, this framework aims to advance understanding of the complex dynamics underlying gender harassment.

The personal aspects in question include characteristics such as aggression, a history of experiencing or witnessing violence, and mental health conditions that can influence a person to carry out violent behavior. Situational aspects include the surrounding environment and stressors influencing behavior, such as economic hardship, substance abuse, and social isolation. These factors can increase tension in relationships and lead to violent outbursts. The socio-cultural aspect involves broader societal norms and cultural practices that perpetuate gender inequality and tolerate violence against women.

Possible solutions to overcome the various causes of violence against women can be divided into levels based on the existing causal factors. On the personal aspect, interventions may include psychological counseling, anger management programs, and mental health support to address individual tendencies toward violence. Increasing economic opportunities and supporting financial stability can reduce stress that leads to violence. In terms of social conditions, efforts should be focused on changing societal norms and attitudes through public awareness campaigns, educational programs that promote gender equality, and strengthening institutional responses to violence against women.

This ecological approach is a new analysis in the study of International Relations (IR), which is a combination of IR studies regarding violence against women in the Philippines, which is the focus of the UN (United Nations), with psychology studies, which include elements of family, social and family economic conditions.

Method

The method used in this study is qualitative that exploring and understanding social phenomena through collecting and analyzing non-numerical data, such as interviews, observations, and textual analysis. Qualitative methods can be used in this research to gain rich insight into the personal, situational, and sociocultural factors that contribute to gender-based violence—using observation methods to observe interactions in families, communities, and institutions to identify behavioral patterns and social dynamics. Qualitative research involves a flexible and iterative process of data collection and analysis. Techniques such as thematic analysis or grounded theory can be used to identify recurring themes, patterns, and relationships in the data. Engaging in a reflexive process of interpretation and interpreting can develop a nuanced understanding of the complexity of gender-based violence and the factors underlying it (Creswell & Poth, 2016).

The data source used in this research is secondary data. Secondary data refers to existing data that has been collected. In this study, secondary data sources include government reports such as those published by the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), which provide statistical data regarding the prevalence and characteristics of violence against women in the Philippines. In addition, reports and publications from international organizations such as the World Health Organization (2013) and UN Women (2020) provide global and regional context to this issue. Journals and academic articles that previously investigated gender-based violence in the Philippines and similar issues were also examined to gather insights and identify gaps in existing knowledge.

Results

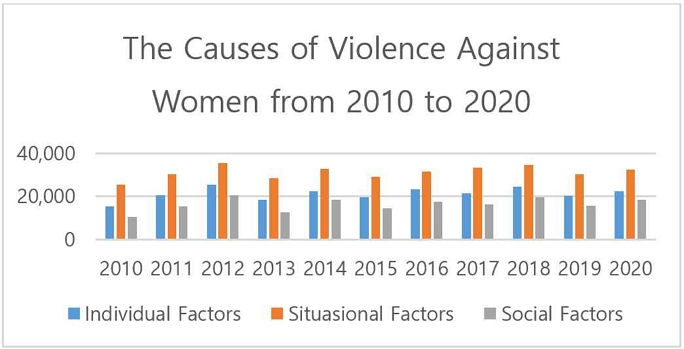

This section presents research findings with a focus on the prevalence and causes of violence against women in the Philippines over a specific period. Figure 1 below illustrates the comparative prevalence of individual, situational, and social factors that cause violence against women in the Philippines from 2010 to 2020.

Factors influencing the occurrence of violence against women in the Philippines. Adapted from Philippine Statistics Authority (2021).

Situational factors consistently emerged as the leading causes of violence against women throughout the research period. These factors peaked, especially in 2012 with 35,481 cases, and in 2018 they reached 34,582 cases. This high and consistent figure shows that problems in the household and intimate relationships are still critical and require targeted intervention.

Individual factors also show a considerable influence, with a marked increase from year to year. Reported cases for individual factors peaked in 2012 at 25,374 and in 2018 at 24,395, an average of around 25,000 cases annually. Despite some fluctuations, individual factors remain significant contributors to violence against women.

Social factors are rarely reported compared to situational and individual factors. The highest number of cases of social factors occurred in 2012, with 20,392 cases, and in 2018, with 19,472 cases, for a total of almost 20,000 cases. This category represents broader societal and community-level influences on violence against women, including cultural norms and societal attitudes. Although the numbers are lower, social factors signal the need for social change, including policy reform and public awareness campaigns to change detrimental gender norms.

Based on the graph below, when viewed as a whole, from year to year, the highest peaks occurred in 2012, 2016, and 2018, which indicates a period of increasing reporting or the possibility of increasing incidents of violence. The lowest figures appeared in 2010 and 2013, indicating potential changes in reporting practices or intervention effectiveness during those years.

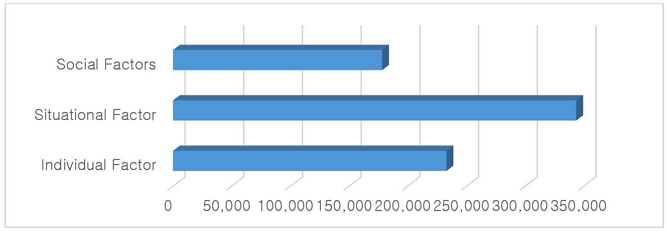

Figure 2 below shows the total number of cases of violence against women, calculated in the 2010-2020 period, where individual, relational, and social factors cause violence against women. The frequency of each perspective is plotted to show the dominance of each factor over the decade.

Our study’s findings are clear: situational factors are the most frequently reported cause of violence against women in the Philippines, with a total of 343,389 cases over a decade. Individual factors follow with 232,906 cases and community factors with 178,082 cases. These results highlight the significant influence of situational dynamics, including male dominance over women in the family, in driving the high levels of violence against women in the Philippines. However, this also presents an opportunity for change. Interventions that target these dynamics have the potential to be highly effective in reducing the incidence of such violence. This understanding underscores the importance of policies and programs that address intimate partner violence and promote healthy relationship dynamics, offering a hopeful path toward combating violence against women in the country.

Discussion

Individual Factors

Individual factors are reflected in personal characteristics and behaviors that can influence power dynamics in relationships and contribute to cases of domestic violence. In cases of sexual harassment against women, individual factors are critical in understanding the dynamics of power and control in a relationship. One significant individual factor is the tendency of husbands and wives to divorce in the Philippines, which can affect the dynamics of family life and contribute to incidents of domestic violence (Jocson & Garcia, 2017). Individual factors are a dynamic framework that focuses on a person’s biological makeup and personal history, which can influence his or her behavior. The personal history in question includes various factors such as childhood experiences, exposure to violence, and learned behavior. For example, individuals who have witnessed or experienced violence in their own families during childhood may be more likely to perpetuate those behaviors in their adult relationships. Additionally, economic stress and financial dependency can play an essential role in domestic violence. Economic factors such as unemployment, low income, and financial instability can increase tensions within the household and make it difficult for victims to leave abusive relationships due to financial dependency (Heise, 1998).

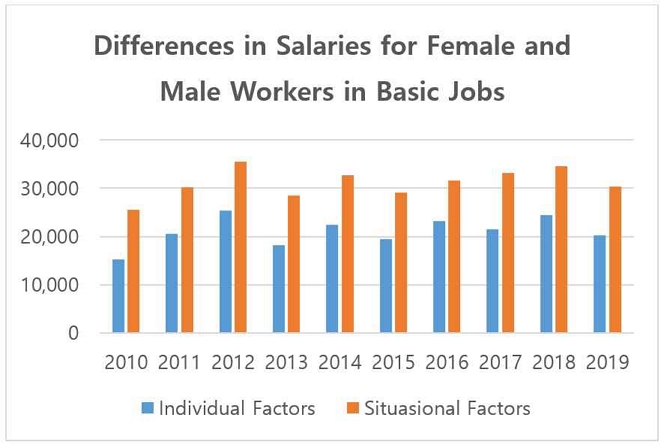

One important factor that harms domestic violence is the low level of income among women and men in the Philippines. According to the Philippine Statistics Authority (2021), in 2018, the average salary of wage workers and men was ₱14,492, compared to ₱12,772 for salaried employees (Philippine Statistics Authority, 2018). Such an economic downturn can lead to reduced household budgets, with women, as primary caregivers, having greater control over currency exchange rates and decision-making processes. Such economic control is often associated with power imbalances, where employees may feel more resentful and defensive toward their coworkers, thereby increasing their level of sensitivity to domestic violence (Antai & Anthony, 2014). Respondents’ mean (geometric) salary was determined to be ₱355.31, with the average wages of men and women being ₱361.60 and ₱344.91, respectively. So, if there were no adjustments, the salary gap would be 4.84% (Engcong, et al., 2019).

Differences in Salaries for Female and Male Workers in Basic Jobs in the Philippines. Adapted from Engcong, et. al. (2019).

Economic uncertainty, a significant risk factor for violence in low-income households, has profound implications for women's autonomy. Those who face financial vulnerability throughout their lives often experience strained relationships due to economic fluctuations and unstable currency values. This can impede women’s progress as they may feel incapable of providing for themselves or their children independently (Vyas & Watts, 2009). For instance, a husband who controls the family income can exploit his financial power to dominate and abuse his wife, who lacks access to financial resources. In this scenario, the wife loses control over family finances and personal autonomy. The husband may only provide money for basic necessities and scrutinize every expense, leaving the wife isolated and unable to seek help or escape an abusive situation. This financial dominance is a tool to maintain control and foster a deep reliance on the wife (Eriksson & Ulmestig, 2021).

The economic disparity between men and women in traditional Filipino households is intricately linked to entrenched gender norms. These norms, which relegate women to the role of primary caretaker and nurse and men to the role of breadwinner, contribute to economic hardship and domestic violence (Quisumbing, 1994). In many traditional Filipino homes, women are expected to fulfill the primary caretaker and nurse role. In contrast, men are expected to establish their careers as stay-at-home parents and child caretakers. The higher earning potential of women in Filipino households bolsters their dominant position in the family structure (Semyonov & Gorodzeisky, 2005).

The correlation between economic control and employment practices in Filipino households has significant implications for women’s economic control and the prevalence of violence. This dynamic can hinder women’s access to education and career guidance, restrict their working hours, and undermine efforts to ensure women’s equality and productivity in the workplace (Schuler, et al., 1996). In many traditional families, women are prohibited from working outside the home and are entirely dependent on their husbands for financial support. This dependence creates a situation where women cannot leave abusive relationships due to their lack of financial independence. Their reliance on their husbands’ income makes them susceptible to domination and control, as their husbands often use their financial power to exert control over every aspect of their wives’ lives (Sorensen & McLanahan, 1987).

The economic downturn has also significantly impacted women's ability to seek opportunities and form strong relationships. Individuals with inadequate financial resources may be unable to afford legal fees, travel expenses, or other necessities necessary to escape a precarious situation. This financial difficulty is caused by decreased access to working hours and wage growth, which affects employees economically (Jocson & Ceballo, 2020). The gender pay gap means women get lower jobs than men, reducing their overall stability. This gap reduces women’s ability to contribute to society, invest in education, and achieve financial stability. As a result, women may feel pressured to remain in less financially stable relationships, which can lead to breakdowns in the household (Blau & Kahn, 1999).

Economic downturns also make it difficult for women to escape tricky situations and obtain the resources they need to protect themselves and their children (Auspurg, Hinz, & Sauer, 2017). For example, a woman who does not have a steady income cannot afford the legal costs of obtaining a restraining order or medical expenses for injuries resulting from domestic violence. This limited access to resources kept him trapped in a cycle of violence because, without adequate financial support, he could not protect himself or seek necessary medical help. This condition is exacerbated by financial dependence on partners, who often use violence as a tool of control and domination (Manning & Saidi, 2010).

The impact of economic downturns and poverty significantly worsens women’s mental health, which can lead to problems with depression, anxiety, and self-harm. These psychological factors increase the tendency to hold negative attitudes toward violence and reduce the ability to find support or strengthen weaker relationships (Roberts et al., 1998).

Economic factors can increase the likelihood of domestic violence against women who have shown signs of having an aggressive personality. A significant stressor that can affect mental health and cause various psychological problems is poor financial management (Gilchrist et al., 2015). Depression, anxiety, and chronic stress can be caused by persistently high demand for necessities and high demands for economic stability. This condition can cause feelings of hopelessness and nostalgia, making it difficult for women to take proactive steps to improve the situation or seek help (Romito, Turan, & De Marchi, 2005).

Financial control can be carried out in several ways, including limiting access to money, regulating loans, and encouraging women to work. Economic hardship in rural areas in the Philippines often results in women’s reduced financial resources, reducing their ability to make independent decisions. This type of violence affects not only women’s economic well-being but also their self-esteem (Postmus, Plummer, McMahon, Murshid, & Kim, 2012).

Women find it difficult to imagine or plan a way out of abusive relationships, trapping them in a cycle of violence and dependency due to minimal financial resources. The psychological impact of the economic crisis is enormous. Financially vulnerable individuals often experience a decrease in self-worth and an increase in daily expenses. This emotional distress may make them less likely to seek help or to sever ties, thus prolonging the cycle of violence (Chant, 1997).

In Southeast Asia, female workers often face discrimination, particularly regarding wages. In the Philippines, women earn only 78% of what male workers receive (Lili Yan Ing, 2023). The government has implemented regulations to encourage women to work abroad as a source of income for the country. A female migrant worker in the Philippines, Mer de Lina (59 years old), explained that she spent most of her life abroad because of the low wages for female workers in the Philippines and the government’s regulations to encourage Filipino women to work abroad. Initially, Mer de Lina worked in Singapore, but more than her salary was needed to meet her family’s basic needs in the Philippines because of the soaring prices. Then, she moved to Hong Kong for 20 years. Her salary in Hong Kong improved, and she moved to Macau, where she only returned to the Philippines in 2017. Mer de Lina’s disappointment with the Philippine government is that it provides low wages for women in her country. However, when working abroad, the protection from the government could be better, so Mer de Lina often cannot rest. The Philippine government’s policy, known as the ‘Labor Export Policy’, has resulted in more Filipinos being forced to work and endure hardships abroad to support their families. In addition to domestic helpers, Filipinas also work abroad in various other jobs, including massage therapists, hotel managers, nurses and chefs. Mer de Lina worked abroad for decades, but her salary while abroad was used up without any money left to support her children while she was away. Her disappointment was compounded, she had to leave her children without adequate compensation. After returning, the suffering of Filipina women also continued as they had to struggle again with receiving a small salary to survive. These sacrifices made by Filipino women should evoke a sense of empathy in the audience (Romano, 2019). In Mer de Lina’s story, the Philippines faces a significant gap between female and male workers, along with the discrimination they endure.

One of the most important strategies to address economic inequality is implementing policies addressing gender-based income inequality. Reducing the gap between men’s and women’s income is critical for economic growth. Let’s envision a future where parental leave policies not only encourage shared childcare responsibilities but also foster a more balanced and supportive society. This, along with encouraging pay transparency and enforcing major equal pay laws, can significantly reduce gender-based income inequality. Increasing women’s access to education and work experience is another essential factor in reducing economic hardship. Providing equal access to high-quality education from an early age will ensure that young people have the abilities and expertise required to be successful in the workplace (Moore, 1987).

Scholarships, mentorship programs, and career counseling should support young women in pursuing higher education and entering high-paying fields traditionally pursued by men. But let's not forget the transformative power of vocational training programs explicitly aimed at women. These programs can empower women by equipping them with the skills and knowledge needed to excel in technology, engineering, and business management. Such empowerment can lead to increased employment opportunities and higher income levels, inspiring personal and professional growth (Duflo, 2012).

Economic reforms, such as microfinance and job training programs, have demonstrated their effectiveness in empowering women financially. Microfinance programs, for instance, provide small loans to individuals to start or expand their businesses. This not only facilitates business operations but also increases income. Moreover, these programs play a crucial role in providing financial information and fostering self-awareness and self-control. As a result, women can now recognize their values and make independent decisions, further enhancing their finances (Kennedy et al., 2017).

Situational Factors

Situational factors are environmental influences that influence the possibility that violence will break out. In the case of violence against women in the Philippines, the most important situational factors are the dominance of Filipino women in household development and the low level of family unity (David & Nadal, 2013). Male dominance in Filipino households is quite strong in religious norms and societal values that prioritize men’s rights. The norms adhered to here lead to deficient environmental protection, which is essential for household hygiene. Traditional gender roles are still prevalent among Filipino families, when the guy is seen as the primary caretaker and head of the household. Current patriarchal structures emphasize men as leaders and providers, while women are expected to uphold the rights of women and children. Men’s roles can lead to an imbalance of power, creating an environment where men feel entitled to control and assert their authority through coercive means (Hoang & Yeoh, 2011).

The societal impact of these factors is profound, with the common perception that men must lead and support their families deeply ingrained in Filipino society. This perception significantly hampers the collective learning and growth of society. The general societal norm is that women must be housewives to manage household affairs and, more importantly, raise their children (Sobritchea, 2004). Men who want to exert control over their partners and children may turn to violence. Often, this violence is used to reinforce traditional gender roles and ensure that women fulfill their responsibilities. In many cases, domestic violence is not only an expression of hostility but also a calculated strategy to increase dominance and control (Jewkes, Flood, & Lang, 2015)

In certain communities, unfortunately there is still a perception that domestic violence is a personal problem that cannot be resolved. This societal attitude can discourage victims from seeking help and deter bystanders from intervening. Traditional practices and beliefs often reinforce the notion that women are subservient to the family, thereby justifying their right to discipline their daughters (García-Moreno et al., 2013). These societal attitudes, coupled with religious beliefs, can further perpetuate the cycle of violence by legitimizing male dominance and making women reluctant to seek opportunities or establish relationships that could potentially lead to violence (Reyes et al., 2022).

Patriarchal norms in many Filipino households dictate that women must respect and be kind to their relatives. The lack of reliable and efficient internet service further hampers the ability to search for resources. Available resources such as counseling centers, courts, and legal aid for domestic violence cases may not meet expectations in many areas. Even after such services are available, societal shame and fear may cause individuals to be reluctant to use them (García-Moreno et al., 2013). This complex web of societal norms and limited resources creates significant barriers for victims, making it even more challenging for them to seek help.

Environmental influence is also essential to increase stress and conflict between family members. Living in small spaces with limited privacy can lead to increased irritability and frequent confrontations. Crowded conditions at the time of birth often lead to increased tension and the possibility of violence. In addition, the lack of personal space in the household can also make it difficult for family members to manage conflict constructively (Jewkes, 2022) Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, some friends are experiencing more severe stress because they are at home. UN Women (2020) reports that one of the consequences of this condition is a significant increase in cases of domestic violence globally. With families facing prolonged periods of isolation and limited access to external support systems, the pandemic is exacerbating existing stress (Viero et al., 2021).

Women who feel betrayed in their journey as breadwinners can relieve feelings of frustration during their journey by using violence as a way to overcome the shortcomings they feel. A significant decrease in work productivity or income can give rise to feelings of annoyance and frustration, which can appear as aggressive behavior toward fellow employees (Schneider, Linder, & Verheyen, 2016). COVID-19 has worsened the current economic situation, affecting many families who have experienced job losses and an unstable currency. Too little personal space can significantly affect group dynamics. When a person does not have the personal space to exercise self-control, this can increase the likelihood of persistent conflict (Akel et al., 2022).

Then, looking at the process of society’s acceptance of male dominance, the dominant role of men in developing household norms that prioritize the needs of observers and individual control. In many cultures, including Filipino culture, traditional beliefs are closely linked to patriarchal structures, where women are supposed to provide the majority of healthcare, both in the public and private spheres (Lee, 2004). Traditional Filipino culture is shaped by patriarchal solid values, where women are seen as the head of the household and men as the subjects of more sentimental matters. Creating an imbalance of power in the household to demand their rights, seek autonomy, or challenge abusive behavior as society accepts for men. This societal structure is shaped by social and religious practices that dictate gender roles. Men are often seen as caregivers and protectors, while women are expected to be homemakers and caretakers.

To address the underlying issues within households, it is crucial to promote gender equality and enforce social norms. Initiatives focusing on communication and empathy are crucial in this regard. One noteworthy program is MenCare, which aims to educate women and children about gender equality and challenge traditional beliefs about masculine traits that contribute to controlling and violent behaviors. MenCare seeks to shift public perceptions of gender relations by promoting positive role models who do not exert authority through control. These programs often include community service projects, educational materials, and public awareness campaigns encouraging people to be compassionate and courageous (Heise & Kotsadam, 2015).

Social Condition Factors

Social factors, the underpinning of societal bonds, exert a profound influence on the perpetuation of violence against women in the Philippines. The urgency of comprehending these factors can not be overstated, as it is crucial for the development of effective interventions to reduce domestic violence (Jewkes et al., 2015) The patriarchal structure of Filipino society, a significant social factor, shapes family dynamics, and community interactions, and cooperative practices. Cultural norms that prioritize the rights of women and the elderly are deeply ingrained in Filipino society, reinforcing the belief that women bear the responsibility to supervise and discipline women, thereby contributing to the normalization of domestic violence (Manderson & Bennett, 2003).

Existing religious beliefs, often intertwined with patriarchal norms, have the effect of diminishing the role of women in traditional households and local communities. In traditional Filipino families, men are heralded as the primary bearers of wisdom and guardians of the family, while women are expected to subordinate elders such as parents and older siblings (Cunneen & Stubbs, 2017). Societies with rigid gender norms and male-dominated power structures exhibit higher rates of domestic violence. The idea that women should be able to physically reprimand men or emotional means is a direct consequence of patriarchal ideology (Enrile & Agbayani, 2007), a concerning aspect that needs to be addressed.

One manifestation of patriarchal control is the dominance over family finances. In many Filipino households, financial resources are entrusted to trustees, granting them significant benefits and control over the family’s finances. This form of conservative economic control diminishes the influence of women’s autonomy and exacerbates their suffering in everyday life (Shohel, Niner, & Gunawardana, 2021). Economic control is a prevalent tactic used by abusers to reinforce interpersonal control and power. The resulting economic uncertainty makes it challenging for women to form strong bonds or share experiences. Fluctuations in currency values can impede an individual’s access to legal documents, safe havens, or other systems necessary to prevent abuse (Stylianou & Dimitriou, 2018) a situation that calls for empathy and understanding.

Gender socialization, a process that starts in childhood, plays a significant role in perpetuating domestic violence. Girls are trained to be kind and selfless, while boys are frequently pushed to be strong and independent. These gender norms, shaped by social institutions like education, media, and family, reinforce harmful stereotypes. For instance, men are typically portrayed in school texts as aggressive and dedicated to their profession, whereas women are typically portrayed as delicate and quiet. Challenging these norms is crucial for reducing domestic violence (Way et al., 2014).

“Pakikisama” and “Utang na Loob” are two religious practices in the Philippines that significantly reduce interpersonal relationships and can indirectly lead to violence. “Pakikisama,” defined as strong interpersonal bonds, refers to religious practices that promote harmony and prevent conflict. In domestic violence, women may feel pressured to form strong bonds with their peers to enforce social stigma and promote group harmony. Women who report violence or seek help often experience pressure to maintain harmony and uphold the family’s reputation because they fear social exclusion or harsh reactions from society (Tan & Davidson, 1994).

In a different view, “Utang na Loob” or “budi-huang”, can also empower women in critical relationships. These religious customs, with their emphasis on reciprocity and loyalty, often require people to remain in a community out of feelings of responsibility or gratitude, even when faced with adversity. This cultural perspective, rather than being a barrier, can be seen as a testament to the resilience of women who, despite societal norms, choose to stay behind and support their families or friends (Van der Kroef, 1966).

Institutions and practices related to religion influence gender roles and societal norms, especially in societies where religious factors are deeply embedded in everyday life. Religious education often promotes traditional gender roles and traditional marriage customs among Filipinos, the majority of whom are of Catholic descent. The Catholic Church often mentions the occurrence of chastity marriage when advocating to safeguard the rights of women.

Media representations and society's attitudes towards violence also influence social norms. Portrayals of women in the media, including television, films, and advertising, often reinforce gender stereotypes and trivialize violence. However, the potential of media campaigns aimed at raising awareness about domestic violence and promoting gender equality in the Philippines should not be underestimated. Despite the cultural norms already pervasive in Filipino society, these campaigns have the power to make a significant impact.

For example, the media often depicts women in submissive roles and men in dominant roles. These representations can normalize power imbalances in relationships and make violence seem acceptable. Efforts to combat this stereotype take the form of advocacy for mutual respect between women and men in the media and educational programs to teach critical media literacy (Tuchman, 2000).

The role of communities and social networks is pivotal in shaping attitudes towards domestic violence. Communities that tolerate or even endorse violence against women create an environment where such behavior is normalized. Social networks can either support or hinder victims’ efforts to seek help and escape abusive situations. In many Filipino communities, the emphasis on the family environment and the need to uphold the family’s reputation can pressure victims into silence about the abuse they endure (Santos et al., 2019). Community-based interventions are crucial in altering these harmful social norms.

Initiatives that involve local leaders, religious institutions, and community members in addressing domestic violence can foster a supportive environment for victims. For instance, the ‘Bantay Familia’ program in the Philippines engages community members in preventing domestic violence through awareness campaigns and support services. The legal and policy framework in the Philippines also reflects and influences social attitudes towards domestic violence. Legislation to Prevent Violence Against Women and Children (Republic of the Philippines, 2004) provides essential protections for women. However, effective implementation and enforcement are needed to ensure the law has a meaningful impact (Bernarte et al., 2018)

Policies that support gender equality and protect women’s rights can help change social norms and reduce the prevalence of domestic violence. In addition, governments and non-governmental organizations must work together to offer complete services, such as legal assistance, therapy, and housing, to victims of domestic abuse. These services are critical to helping women escape violent situations and rebuild their lives.

Conclusions

Violence against women remains a critical issue globally that impacts public health and human rights. In the Philippines, despite important legislative initiatives like the Magna Carta of Women and the Anti-Violence Against Women and Children Law (Republic of the Philippines, 2009), violence against women in the Philippines is still ongoing and deeply rooted in cultural norms and societal structures. The research focuses on the Philippines because, among ASEAN countries, the Philippines is a country with a very high level of violence against women. Heise’s ecological theory highlights the complex interactions between individual, situational, and social factors that make gender-based violence more common in the Philippines.

The findings of this research reveal that situational factors are the most significant contributor to violence against women. Situational factors include dynamics in couple relationships and family structures, where male dominance and control often lead to various forms of abuse. These findings align with Heise's ecological framework, which emphasizes the importance of considering multiple levels of influence in understanding and addressing gender-based violence. Individual factors also play an essential role.

The ecological framework thoroughly examines the influence of violence in the Philippines, so it is hoped that after comprehensive knowledge from an ecological perspective, there will be less violence against women in the Philippines. Policies and programs must target all levels of the social ecology to create lasting change.

Acknowledgments

The research leading to these results was supported by the Research and Technology Transfer Office (RTTO) at Binus University Jakarta.

References

-

Akel, M., Berro, J., Rahme, C., Haddad, C., Obeid, S., & Hallit, S. (2022). Violence Against Women During COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(13–14), NP12284–NP12309. Retrieved from

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260521997953]

-

Antai, D., Antai, J., & Anthony, D. S. (2014). The relationship between socio-economic inequalities, intimate partner violence, and economic abuse: A national study of women in the Philippines. Global Public Health, 9(7), 808–826.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2014.917195]

-

Antai, D., Oke, A., Braithwaite, P., & Lopez, G. B. (2014). The Effect of Economic, Physical, and Psychological Abuse on Mental Health: A Population-Based Study of Women in the Philippines. International Journal of Family Medicine, 2014, 1–11. Retrieved from

[https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/852317]

-

Auspurg, K., Hinz, T., & Sauer, C. (2017). Why Should Women Get Less? Evidence on the Gender Pay Gap from Multifactorial Survey Experiments. American Sociological Review, 82(1), 179–210.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122416683393]

- Bernarte, R. P., Quennie Marie M. Acedegbega, Fadera, M. L. A., & Yopyop, H. J. G. (2018). Violence against women in the Philippines. Asia Pacific Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, 6(1), 117–124.

-

Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (1999). Analyzing the gender pay gap. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 39(5), 625–646.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S1062-9769(99)00021-6]

-

Chant, S. (1997). Women-Headed Households: Poorest of the Poor?: Perspectives from Mexico, Costa Rica, and the Philippines. IDS Bulletin, 28(3), 26–48.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.1997.mp28003003.x]

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2016). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th edition). London: Sage Publications.

-

Cunneen, C., & Stubbs, J. (2017). Migration, Political Economy and Violence Against Women: The Post Immigration Experiences of Filipino Women in Australia. In Migration, Culture Conflict and Crime (pp. 159–184). London: Routledge

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315202358-11]

-

Dalal, K. (2011). Does economic empowerment protect women from intimate partner violence? Journal of Injury and Violence Research, 3(1), 35–44.

[https://doi.org/10.5249/jivr.v3i1.76]

-

David, E. J. R., & Nadal, K. L. (2013). The colonial context of Filipino American immigrants’ psychological experiences. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 19(3), 298–309.

[https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032903]

-

Duflo, E. (2012). Women Empowerment and Economic Development. Journal of Economic Literature, 50(4), 1051–1079.

[https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.50.4.1051]

- Engcong, G. E., Lim-Polestico, D. Lou, Yungco, N. C., & Liwanag, J. A. M. (2019). On The Gender Pay Gap in The Philippines and The Occupational Placement and Educational Attainment. Do not capitalize all words in the title, need more information about the publication type.

-

Enrile, A., & Agbayani, P. T. (2007). Differences in Attitudes Towards Women Among Three Groups of Filipinos: Filipinos in the Philippines, Filipino American Immigrants, and U.S. Born Filipino Americans. Journal of Ethnic And Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 16(pp. 1–2), 1–25.

[https://doi.org/10.1300/J051v16n01_01]

-

Eriksson, M., & Ulmestig, R. (2021). “It’s Not All About Money”: Toward a More Comprehensive Understanding of Financial Abuse in the Context of VAW. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(3–4), NP1625-1651NP.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517743547]

- García-Moreno, C., Pallitto, C., Devries, K., Stöckl, H., Watts, C., & Abrahams, N. (2013). Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. World Health Organization.

-

Gilchrist, G., Blazquez, A., Segura, L., Geldschläger, H., Valls, E., Colom, J., & Torrens, M. (2015). Factors associated with physical or sexual intimate partner violence perpetration by men attending substance misuse treatment in Catalunya: A mixed methods study. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 25(4), 239–257.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/cbm.1958]

-

Heise, L. L. (1998). Violence Against Women. Violence Against Women, 4(3), 262–290.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801298004003002]

-

Heise, L. L., & Kotsadam, A. (2015). Cross-national and multilevel correlates of partner violence: an analysis of data from population-based surveys. The Lancet Global Health, 3(6), e332–e340.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00013-3]

-

Hoang, L. A., & Yeoh, B. S. A. (2011). Breadwinning Wives and “Left-Behind” Husbands. Gender & Society, 25(6), 717–739.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243211430636]

-

Jewkes, R. (2022). Increased risk of intimate partner violence among military personal requires effective prevention programming. The Lancet Regional Health - Europe, 20, 100456.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100456]

-

Jewkes, R., Flood, M., & Lang, J. (2015). From work with men and boys to changes of social norms and reduction of inequities in gender relations: a conceptual shift in prevention of violence against women and girls. The Lancet, 385(9977), 1580–1589.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61683-4]

-

Jocson, R. M., & Ceballo, R. (2020). Resilience in low-income Filipino mothers exposed to community violence: Religiosity and familism as protective factors. Psychology of Violence, 10(1), 8–17.

[https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000216]

-

Jocson, R. M., & Garcia, A. S. (2017). Low-Income Urban Filipino Mothers’ Experiences With Community Violence. International Perspectives in Psychology, 6(3), 133–151.

[https://doi.org/10.1037/ipp0000071]

-

Kennedy, T., Rae, M., Sheridan, A., & Valadkhani, A. (2017). Reducing gender wage inequality increases economic prosperity for all: Insights from Australia. Economic Analysis and Policy, 55, 14–24.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2017.04.003]

-

Lee, R. B. (2004). Filipino men’s familial roles and domestic violence: implications and strategies for community-based intervention. Health and Social Care in the Community, 12(5), 422–429.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2004.00512.x]

- Lili Yan Ing. (2023, May 13). Inklusivitas ASEAN bagi Perempuan, Anak Muda, dan Penyandang Disabilitas. Investor.Id. Retrieved from https://investor.id/investory/329379/inklusivitas-asean-bagi-perempuan-anak-muda-dan-penyandang-disabilitas/all

-

Mandal, M., & Hindin, M. J. (2015). Keeping it in the Family: Intergenerational Transmission of Violence in Cebu, Philippines. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 19(3), 598–605.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-014-1544-6]

- Manderson, L., & Bennett, L. R. (2003). Violence Against Women In Asian Societies. London: Psychology Press.

-

Manning, A., & Saidi, F. (2010). Understanding the Gender Pay Gap: What’s Competition Got to Do with it? ILR Review, 63(4), 681–698.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/001979391006300407]

-

McDoom, O. S., Reyes, C., Mina, C., & Asis, R. (2019). Inequality Between Whom? Patterns, Trends, and Implications of Horizontal Inequality in the Philippines. Social Indicators Research, 145(3), 923–942.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-1867-6]

-

Moore, K. M. (1987). Women’s Access and Opportunity in Higher Education: toward the twenty‐first century. Comparative Education, 23(1), 23–34.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/0305006870230104]

-

Okenwa-Emgwa, L., & von Strauss, E. (2018). Higher education as a platform for capacity building to address violence against women and promote gender equality: the Swedish example. Public Health Reviews, 39(1), 31.

[https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-018-0108-5]

- Philippine Statistics Authority. (2018). National Demographic and Health Survey 2017.

- Philippine Statistics Authority. (2021). Statistics on Women and Men in Central Visayas (Population, Employment and Literacy).

-

Postmus, J. L., Plummer, S.-B., McMahon, S., Murshid, N. S., & Kim, M. S. (2012). Understanding Economic Abuse in the Lives of Survivors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(3), 411–430.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260511421669]

-

Quisumbing, A. R. (1994). Intergenerational transfers in Philippine rice villages. Journal of Development Economics, 43(2), 167–195.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3878(94)90003-5]

- Republic of the Philippines. (2004). Republic Act No. 9262.

- Republic of the Philippines. (2009). Republic Act No. 9710.

-

Reyes, M. E., Weiss, N. H., Swan, S. C., & Sullivan, T. P. (2022). The Role of Acculturation in the Relation Between Intimate Partner Violence and Substance Misuse Among IPV-victimized Hispanic Women in the Community. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(9–10), NP7057–NP7081.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520967134]

-

Roberts, G. L., Lawrence, J. M., Williams, G. M., & Raphael, B. (1998). The impact of domestic violence on women’s mental health. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 22(7), 796–801.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-842X.1998.tb01496.x]

- Romano, K. (2019, March 14). Tenaga Kerja Wanita Masih Menjadi “Ekspor Utama” Filipina. Indonesia.Ucannews. https://indonesia.ucanews.com/2019/03/14/tenaga-kerja-wanita-masih-menjadi-ekspor-utama-filipina/

-

Romito, P., Molzan Turan, J., & De Marchi, M. (2005). The impact of current and past interpersonal violence on women’s mental health. Social Science & Medicine, 60(8), 1717–1727.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.026]

-

Santos, V. R., Monteiro, B., Martinho, F., dos Reis, I. P., & Sousa, M. J. (2019). Employer branding: The power of attraction in the EB group. Journal of Reviews on Global Economics, 8, 118–129.

[https://doi.org/10.6000/1929-7092.2019.08.12]

-

Schneider, U., Linder, R., & Verheyen, F. (2016). Long-term sick leave and the impact of a graded return-to-work program: evidence from Germany. The European Journal of Health Economics, 17(5), 629–643.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-015-0707-8]

-

Schuler, S. R., Hashemi, S. M., Riley, A. P., & Akhter, S. (1996). Credit programs, patriarchy and men’s violence against women in rural Bangladesh. Social Science & Medicine, 43(12), 1729–1742.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00068-8]

-

Semyonov, M., & Gorodzeisky, A. (2005). Labor Migration, Remittances and Household Income: A Comparison between Filipino and Filipina Overseas Workers. International Migration Review, 39(1), 45–68.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2005.tb00255.x]

-

Serquina-Ramiro, L., Madrid, B. J., & Amarillo, Ma. L. E. (2004). Domestic Violence in Urban Filipino Families. Asian Journal of Women’s Studies, 10(2), 97–119.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/12259276.2004.11665971]

-

Shohel, T. A., Niner, S., & Gunawardana, S. (2021). How the persistence of patriarchy undermines the financial empowerment of women microfinance borrowers? Evidence from a southern sub-district of Bangladesh. PLOS ONE, 16(4), e0250000.

[https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250000]

-

Shoultz, J., Magnussen, L., Manzano, H., Arias, C., & Spencer, C. (2010). Listening to Filipina Women: Perceptions, Responses and Needs Regarding Intimate Partner Violence. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 31(1), 54–61.

[https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840903200043]

- Sobritchea, C. I. (2004). Gender, Culture & Society: Selected Readings In Women’s Studies In The Philippines. Seoul: Ewha Womans University Press.

-

Sorensen, A., & McLanahan, S. (1987). Married Women’s Economic Dependency, 1940-1980. American Journal of Sociology, 93(3), 659–687.

[https://doi.org/10.1086/228792]

-

Stalans, L. J., & Lurigio, A. J. (1995). Responding to Domestic Violence Against Women. Crime & Delinquency, 41(4), 387–398.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128795041004001]

-

Stylianou, K., & Dimitriou, L. (2018). Analysis of Rear-End Conflicts in Urban Networks using Bayesian Networks. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2672(38), 302–312.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0361198118790843]

-

Tan, J., & Davidson, G. (1994). Filipina‐Australian marriages: further perspectives on spousal violence. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 29(3), 265–282.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1839-4655.1994.tb01012.x]

-

Tsai, L. C. (2017). The Process of Managing Family Financial Pressures Upon Community Reentry Among Survivors of Sex Trafficking in the Philippines: A Grounded Theory Study. Journal of Human Trafficking, 3(3), 211–230.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/23322705.2016.1199181]

-

Tuchman, G. (2000). The Symbolic Annihilation of Women by the Mass Media. In Culture and Politics (pp. 150–174). New York: Palgrave Macmillan US. Retrieved from

[https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-62397-6_9]

- UN Women. (2020). Ending violence against women.

-

Van der Kroef, J. M. (1966). Patterns of Cultural Conflict in Philippine Life. Pacific Affairs, 39(3/4). Retrieved from

[https://doi.org/10.2307/2754276]

-

Viero, A., Barbara, G., Montisci, M., Kustermann, K., & Cattaneo, C. (2021). Violence against women in the Covid-19 pandemic: A review of the literature and a call for shared strategies to tackle health and social emergencies. Forensic Science International, 319, 110650. Retrieved from

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2020.110650]

-

Vizcarra, B., Hassan, F., Hunter, W. M., Muñoz, S. R., Ramiro, L., & De Paula, C. S. (2004). Partner violence as a risk factor for mental health among women from communities in the Philippines, Egypt, Chile, and India. Injury Control and Safety Promotion, 11(2), 125–129.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/15660970412331292351]

-

Vyas, S., & Watts, C. (2009). How does economic empowerment affect women’s risk of intimate partner violence in low and middle income countries? A systematic review of published evidence. Journal of International Development, 21(5), 577–602.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1500]

-

Way, N., Cressen, J., Bodian, S., Preston, J., Nelson, J., & Hughes, D. (2014). “It might be nice to be a girl... Then you wouldn’t have to be emotionless”: Boys’ resistance to norms of masculinity during adolescence. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 15(3), 241–252.

[https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037262]

-

Widom, C. S., & Wilson, H. W. (2014). Violence and Mental Health. In Intergenerational Transmission of Violence (pp. 27–45). New York City: Springer, Dordrecht.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8999-8_2]

- World Health Organization. (2013). Global and regional estimates of violence against women.

- Yoon, G. H., & Bor, J. (2020). Effect of education on the risk of gender-based violence in the Philippines. Philippine Journal of Health Research and Development, 24(2).

Biographical Note: Tia Mariatul Kibtiah is an Associate Professor and Faculty Member at the Department of International Relations at Binus University. Her research, published in international journals indexed by Scopus, has significantly contributed to the fields of Middle Eastern Studies, Public Diplomacy, Foreign Policy, Terrorism, Gender, and more recently, Energy. For example, her recent work on the gender dynamics of energy policy in the Middle East has sparked new discussions and debates in the academic community. Her ORCID ID is https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7004-1076 E-mail: tia.kibtia001@binus.ac.id

Biographical Note: Najwa Divara Tuharea is a student majoring in International Relations at Binus University. During her studies, she was active in various activities such as international seminars and education volunteering. Her focus and interests are Gender, Foreign Policy, and International Media. E-mail: najwa.tuharea@binus.ac.id