Beyond Gender: Analyzing Women Legislators’ Influence in Assembly Deliberations through Structural Topic Modeling

Abstract

This paper explores the substantive representation of female lawmakers in the Korean National Assembly (KNA). By analyzing gender differences in deliberations from the minutes of 23 standing committees during the 19th KNA, the study examines how women lawmakers contribute to parliamentary discussions. The findings show that women are not only more active on traditionally “women’s issues” such as education, health, and welfare (topics 2, 4, 11), but they also play a significant role in areas less commonly associated with female lawmakers. These include confirmation hearings (topic 17), budget planning and execution (topic 9), and union repression (topic 20). Female lawmakers were found to be more engaged than their male counterparts in these discussions, challenging the assumption that women primarily focus on gender-specific issues. The study concludes that female lawmakers, as descriptive representatives, effectively act as substantive representatives by advocating for women's interests and engaging deeply in broader national issues. These findings highlight the evolving role of women in legislative bodies and suggest that female lawmakers are active participants in a wide range of policy areas, contributing to both gender equality and overall legislative effectiveness.

Keywords:

Descriptive representation, substantive representation, women’s political representation, Korean National Assembly, structural topic modelingIntroduction

The underrepresentation of women in political institutions has long been a concern in discussions on democratic equality and justice. Scholars have explored whether increasing the number of women in legislative bodies, known as descriptive representation, leads to substantive representation, where women legislators actively promote policies benefiting women (Franceschet & Piscopo, 2008; Pitkin, 1967). While much research has focused on legislative outputs such as bill proposals and voting behavior, less attention has been paid to the crucial deliberative processes shaping legislative outcomes (Dolan & Ford, 1995; Schwindt-Bayer, 2006). Deliberation is key to determining the final shape of legislation (Mansbridge, 1999).

In the context of the Korean National Assembly (KNA), studies on gender and political representation have similarly focused on outputs like bill sponsorship or voting patterns (Jeon, 2009; Seo, 2010). However, these studies overlook the critical role women play in standing committees, where most legislative review and debate occur (Davidson & Oleszek, 2008). These committees are central to the legislative process, making them crucial site for evaluating whether female lawmakers substantively represent women’s interests.

During the 19th National Assembly (2012-2016), two major parties dominated the political landscape: the Saenuri Party (governing party) with 158,131 remarks and the Democratic Party (opposition) with 202,324 remarks. Other parties included the Unified Progressive Party (12,225 remarks), the Liberty Forward Party (3,406 remarks), and the People’s Party (299 remarks), with independent members making 4,845 remarks. The Saenuri Party, while supporting the gender quota system, maintained conservative positions on gender issues, often prioritizing family values. In contrast, the Democratic Party advocated for more progressive gender policies, including stronger workplace discrimination laws and expanded childcare support. This partisan divide on gender issues provides an important backdrop for understanding women legislators’ activities across party lines.

Women legislators comprised 15.67% of the 19th assembly, reflecting their continued underrepresentation in Korean politics. Despite their numerical minority, female lawmakers demonstrated substantial legislative engagement, accounting for 69,326 remarks compared to 311,904 by male legislators. Notably, their average speech length was significantly longer at 185 characters compared to 154 characters for male lawmakers, suggesting more detailed and substantive contributions to legislative discussions. Their active participation in parliamentary deliberations, particularly in standing committees where crucial policy discussions take place, underscores their influence in shaping legislative outcomes.

South Korea provides a relevant case for studying gender representation due to its recent implementation of gender quotas and the increasing salience of gender issues in the political landscape (Liu, 2018). Gender equality movements and the politicization of women’s rights make the KNA an ideal setting to examine whether increased descriptive representation translates into substantive outcomes (Kweon & Ryan, 2022; Lee & Lee, 2013). Furthermore, South Korea’s status as a consolidating democracy in East Asia offers insights into how gender representation functions in non-Western contexts, where traditional gender roles coexist with rapid socio-political changes (Lee & Lee, 2020).

This paper aims to fill the gap in the literature by applying Structural Topic Modeling (STM) to analyze the minutes of all standing committee meetings held during the 19th KNA (2012-2016). STM allows for the analysis of large-scale legislative data to identify latent topics in lawmakers’ speeches (Blei et al., 2003; Roberts et al., 2013). By examining the prevalence of these topics and how male and female legislators engage with them, we assess whether female lawmakers are more active in promoting traditionally “women’s issues” like childcare and welfare, or whether their participation extends to broader policy areas.

Additionally, this study considers the impact of the Sewol disaster, a tragic ferry sinking that claimed the lives of hundreds of passengers, including many students, which significantly shaped national discourse on safety, education, and government accountability. While our analysis does not indicate stark differences in topic engagement before and after the disaster, the incident remains a pivotal moment that may have subtly influenced how lawmakers addressed issues related to safety and welfare in their deliberations.

Our findings confirm that women legislators are more vocal on issues related to education, social welfare, and child safety. However, contrary to stereotypes, female lawmakers are also significantly engaged in broader areas, such as budget planning, union repression, and confirmation hearings. These results suggest that female lawmakers are not limited to gender-specific issues but are active across a wide range of policy domains.

By focusing on deliberation, this study expands the scope of existing research on gender and political representation. Our use of STM demonstrates the potential of text-mining techniques to analyze large-scale legislative data, opening new avenues for research. The findings not only contribute to the growing literature on women’s substantive representation but also challenge assumptions about the scope of women lawmakers’ political engagement. This study has important implications for understanding the broader roles that female legislators play in shaping policy and the impact of increasing women’s representation in political institutions (Carroll, 2001; Mansbridge, 1999).

Literature Overview

Research on women’s political representation has long debated the link between descriptive representation—the presence of women in legislative bodies—and substantive representation, which refers to actions taken by women legislators to advance women’s interests (Pitkin, 1967). Foundational studies by Carroll (2001) and Franceschet & Piscopo (2008) highlighted that while increasing the number of women in legislatures is essential, it does not always guarantee substantive representation. More recent work, such as Celis et al. (2014), has emphasized the complex nature of women’s interests, arguing that they cannot be universally defined and may shift depending on the political, cultural, and institutional context.

In the theoretical discourse surrounding women's interests, scholars have proposed two primary approaches: exogenous and endogenous. The exogenous approach defines women’s interests based on predetermined issues traditionally associated with women, such as childcare, health, and education (Reingold, 2003). This approach assumes a fixed set of issues that inherently align with women’s experiences and needs. On the other hand, the endogenous approach criticizes this view for being overly essentialist, arguing that women’s interests are not fixed and can evolve based on political, social, and institutional factors (Celis, 2008). From an endogenous perspective, female legislators redefine and expand women’s interests by engaging in broader policy areas, such as labor rights and economic policy, which are not traditionally seen as “women’s issues.” This broader understanding of women’s representation is crucial for capturing the full spectrum of women’s political behavior.

In South Korea, research on gender and political representation has typically focused on legislative outputs, such as bill sponsorship and voting behavior (Jeon, 2009; Seo, 2010). These studies have been crucial in demonstrating that women legislators are often more likely to sponsor bills related to education, welfare, and childcare—issues traditionally associated with women’s interests (Kim, 2011; Lee & Lee, 2020). However, these studies leave a significant gap by overlooking the deliberative processes that take place within standing committees, where much of the substantive legislative work occurs. Committees are where policies are shaped and debated before reaching the plenary session, and understanding women’s participation in these deliberations is essential for a more comprehensive view of substantive representation (Schwindt-Bayer, 2006).

Moreover, the scope of this research has often been limited to the South Korean context, missing opportunities for broader comparative analysis. By integrating insights from other East Asian countries, such as Japan and Taiwan, as well as global trends in women’s political representation, this study can offer a richer understanding of the dynamics at play. For example, Joshi & Echle (2023) examined women’s representation in Japan and found that while women were underrepresented in leadership positions, they played crucial roles in social welfare and education policymaking, much like their South Korean counterparts. In Taiwan, Huang (2016) showed that gender quotas led to increased participation of women in legislative debates, particularly in areas such as healthcare and labor rights. This finding is particularly significant as it challenges traditional assumptions about women legislators’ policy focuses in East Asian contexts. Huang’s research demonstrated that female legislators actively engaged in labor rights discussions, recognizing these issues as fundamentally connected to women’s economic empowerment and workplace equality. This pattern of engagement suggests that women’s substantive representation in East Asian legislatures may extend beyond conventionally defined women’s issues.

Recent global studies, such as Krook & Zetterberg (2016) and Wang (2014), highlight that women’s political representation has become a key factor in shaping gender-sensitive policies worldwide, but also point to persistent challenges in achieving full substantive representation, particularly in male-dominated fields like defense and finance. By situating South Korea’s experience within these broader trends, this study contributes to ongoing debates on how institutional design, such as gender quotas, can enhance women’s legislative impact in diverse political systems(Shim, 2021; Shin, 2023).

While much of the literature has focused on outputs such as bill sponsorship, this paper shifts attention to the deliberative processes within standing committees, providing a more nuanced understanding of how women legislators engage with both gender-specific and broader national issues. Recent studies, such as Liu (2018) and Kweon & Ryan (2022), further support the argument that women’s presence in legislatures not only promotes gender-specific agendas but also enhances the quality of democratic deliberation as a whole. These studies underscore the importance of analyzing how women navigate institutional settings and contribute to a wider array of policy areas beyond traditional gender concerns.

A recent comprehensive analysis in “Substantive Representation of Women in Asian Parliaments” (Joshi & Echle, 2023) provides important comparative insights into how female legislators navigate institutional constraints across East Asian democracies. Their analysis suggests that while the pathways to parliament may differ, women legislators across East Asia show similar patterns in expanding their legislative influence beyond traditionally gendered policy domains. This regional perspective helps contextualize the Korean case within broader East Asian patterns of women’s legislative behavior.

By focusing on the 19th National Assembly and using Structural Topic Modeling (STM) to analyze committee minutes, this study contributes to the growing body of literature that explores the relationship between descriptive and substantive representation. It not only builds on previous findings but also opens new avenues for research by incorporating contemporary methodological approaches and drawing connections with regional and global trends in women’s political behavior.

Building on the existing literature, our theoretical framework focuses on two key aspects of women’s legislative behavior. First, we argue that female legislators’ engagement is rooted in their role as substantive representatives of women’s interests. Studies have consistently shown that descriptive representation often leads to substantive representation, with women legislators being more active in areas traditionally associated with women’s concerns (Carroll, 2001; Pitkin, 1967). This pattern reflects both their lived experiences and their understanding of women constituents’ needs.

Second, as women gain more institutional experience and political influence, their legislative engagement tends to expand beyond traditionally defined women’s issues. This expansion reflects both the evolution of women’s political roles and their growing institutional capacity. As Huang’s (2016) research on Taiwan’s legislature demonstrates, women legislators can effectively engage in broader policy domains while maintaining their commitment to core women’s interests.

Based on these theoretical foundations, we hypothesize that:

- H1: Female legislators will show higher levels of engagement in traditionally defined women’s issues (such as education, welfare, and health).

- H2: While maintaining their engagement in traditional women’s issues, female legislators will demonstrate significant participation in broader policy and oversight domains.

- H3: The pattern of women’s legislative engagement will show meaningful variation over time, reflecting the dynamic nature of women’s substantive representation.

This theoretical framework helps us understand both the persistence of women’s attention to traditional gender-related issues and their expanding role in broader policy domains. It suggests that women’s substantive representation evolves as female legislators gain experience and influence in legislative bodies, while maintaining their core representative function.

Data and Analysis Method

This study analyzes the 19th National Assembly (2012-2016) to examine recent legislative patterns while avoiding potential analytical distortions from subsequent political disruptions. While our research aims to investigate contemporary legislative behavior, more recent assemblies present significant methodological challenges. The 22nd Assembly (2024-) is too nascent for comprehensive analysis, while the 21st Assembly (2020-2024) was characterized by the emergence of a supermajority party that held more than half of parliamentary seats, and coincided with major electoral events including presidential and local elections. The 20th Assembly (2016-2020) was marked by extraordinary political circumstances surrounding the presidential impeachment process. These political upheavals in the 20th and 21st Assemblies could potentially confound the analysis of gender effects in legislative behavior. Therefore, the 19th Assembly represents the most recent period suitable for systematic analysis of gendered patterns in legislative deliberations, offering a relatively stable political environment that preceded these institutional disruptions.

This study analyzes data from twenty-three standing committees held during the 19th Korean National Assembly (KNA). To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive analysis of committee speeches throughout the entire 19th KNA period. The dataset includes around one million speech records, along with metadata such as committee name, date, speaker, and other identifying details.

In our analysis, we included the Sewol ferry disaster as a critical temporal marker for several theoretical and methodological reasons. The tragic event of April 16, 2014, marked a significant shift in public discourse around safety regulations and government oversight, particularly concerning children’s welfare. The disaster, which claimed the lives of 304 people, mostly high school students, led to intense legislative scrutiny of safety policies and institutional responsibilities (Lee, 2018). This event is particularly relevant to our study as it intersects with key areas of legislative concern - child safety, education, and institutional accountability. Moreover, as our research examines patterns in legislative engagement across different policy domains, the Sewol disaster provides an important point of reference for analyzing potential shifts in legislative discourse and priorities.

We enhanced the dataset by adding speaker gender and political party affiliation. For speeches after the Sewol disaster, we coded the variable as 1, and 0 otherwise. To prepare the data for topic modeling, we tokenized each speech using KoNLPy and MeCab libraries in Python, extracting Proper Nouns and Common Nouns. Frequently occurring but uninformative words (stopwords) were identified and removed through frequency analysis. The processed data was then exported to R for further analysis.

Descriptive Statistics

The three categories of speech records made during the overall meeting period of the 19th Standing Committee of the National Assembly (2012-07-10 to 2016-05-17) are arranged into a cross-table, see Table 1. The speakers on the Legislation and Judiciary Committee, the Democratic Party speakers, and men speakers in general spoke the most. On the other hand, based on the average length of speech per remark (number of letters), but not the number of remarks themselves, the results differ, with the longest average length of speech being held on the Women’s Family Committee, by a representative of the People’s Party, and by women in general.

Structural Topic Model (STM)

Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA; Blei et al., 2003) has been widely used to uncover hidden themes in large text datasets. It is effective in identifying underlying patterns and classifying documents based on their content (Li et al., 2010; Vogel & Jurafsky, 2012; Wang et al., 2013). Recently, this method has been extended to incorporate metadata, allowing for more nuanced analyses of how topics relate to specific document-level features. Structural Topic Modeling (STM; Roberts et al., 2013) builds on this by discovering relationships between topics and metadata (Roberts et al., 2014).

Key features of STM include: a. Estimating correlations between topics b. Incorporating metadata as covariates in the topic modeling process c. Analyzing how metadata influences both the prevalence of topics and the content of documents.

Unlike LDA, which estimates topic proportions at the corpus level, STM allows for document-level analysis, making the topics more interpretable by linking them to metadata such as speaker gender or party affiliation. STM can also track changes over time by fitting nonlinear relationships between metadata and topics, providing a powerful tool for analyzing temporal trends.

Roberts et al. (2014) developed the stm package in R, which implements the STM algorithm. This package includes tools for estimating topic models and provides various visualization options to help interpret the results.

Unlike Blei et al. (2007) in which topic proportion and term priors are provided at corpus-level, the second feature shows a distinctive interpretability of the STM’s topics, which is a function of the meta-data. This functional relationship uses two independent components: topic prevalence covariates have a functional relationship with the expected topic proportion at a document level, while the topical content covariate represents the distribution of words within each document. Figure 1 (Roberts et al., 2013) graphically shows how STM incorporates the document generation process with these covariates. Since STM can fit B-splines and nonlinear covariate effects to the expected topic proportions, one can track the diverging effects of specific covariate information (such as the speaker’s gender) in a time-series framework.

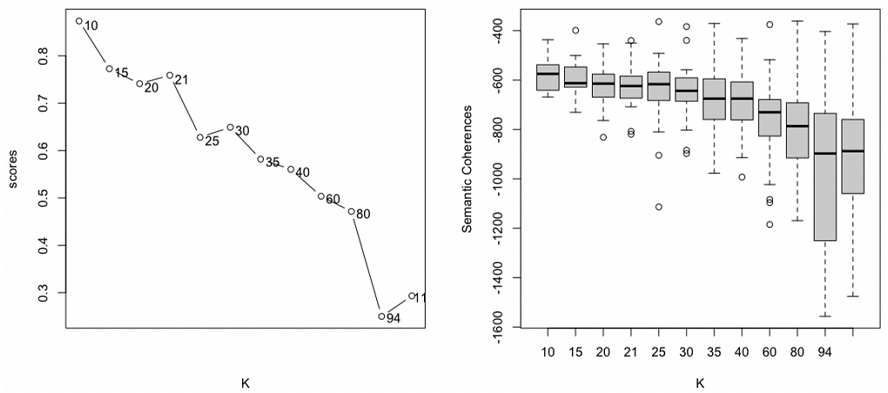

Model performances by K Scores.*These scores (the left pane) are averaged values of the scaled held-out likelihoods and semantic coherence.

Roberts et al. (2016) implemented a comprehensive R package for STM, called stm, that incorporates various topic estimation and post-estimate evaluation tools as well. It uses a partially-collapsed variational expectation-maximization algorithm in order to estimate the model parameters, and offers simple but informative interpretative and visualization tools.

Model Selection

Like other topic models, STM requires selecting the number of topics (denoted as K). Although there is no consensus on the best way to determine K, one common approach is to evaluate models using held-out likelihood (Wallach et al., 2009) and semantic coherence (Mimno et al., 2011).

- ⦁ Held-out likelihood measures how well the model generalizes to unseen data by fitting the model on a portion of the corpus with some terms excluded. This helps prevent overfitting.

- ⦁ Semantic coherence assesses how well the words in each topic fit together in a meaningful way, making it easier for humans to interpret the topics (Mimno et al., 2011).

By combining these two measures, we can select a model that balances generalizability with interpretability.

Our voluminous dataset (a corpus with about 5 million tokens and 381,000 documents) demanded intensive computations for each model fitting. For example, fitting a model with K = 80 on a notebook computer equipped with eight virtual CPUs and 32GB of memory took about 1.5 days. Given this, we initially needed a practical set of hyperparameters and used STM’s spectral initialization to determine an initial value for K (Mimno & Lee, 2014), obtaining K = 94.

To refine the model, we searched for the optimal value of K based on two model quality measures: held-out likelihoods and semantic coherence. While the model with K = 10 had the highest held-out likelihood and semantic coherence, we ultimately selected K = 21 for its superior interpretability and more clearly distinct topics, balancing both coherence and practical understanding of the content. We used the top keywords in Figure 1 to label each topic and inspected collections of documents most relevant to the twenty-one topics to improve the quality of the topic labels.

To ensure the robustness of our findings, we conducted sensitivity analyses by varying the number of topics (K) by increments of 3-5, specifically testing K = 18 and K = 24. Our main findings regarding gender differences in topic engagement remained consistent across different values of K, demonstrating the stability of our results.

Women Members’ Representation in the Process of Committee Consideration

A key function of STM is estimating the effects of topic type and content covariates on expected topic proportions. In this study, we used two covariates to explore the following models:

- 1. Expected Topic Ratio ∼ gender * date + party * date

- 2. content ∼ Sewol Ferry_dummy

We first considered the marginal effects of gender and party, then divided the entire period into two parts—before and after the Sewol ferry disaster—to analyze differences in keyword selection within each topic. The date variable was included as an interaction term to examine how expected topic proportions changed over time by gender and party affiliation.

The results were obtained by setting gender and party affiliation as covariates for topic trends, while dividing the dataset into two time periods to account for the Sewol ferry disaster (Lee, 2018). This allowed us to track how keyword selections within each topic varied. The model includes conference date covariates as interaction terms, enabling us to observe changes in gender and party effects on topic proportions over time. Table 2 provides the top keywords and related statements for each topic, which were used to assign descriptive titles.

The key topics identified include:

- ⦁ Topic 1: Question and meeting progress

- ⦁ Topic 2: Nurture and social welfare (child-care policy)

- ⦁ Topic 3: Agricultural and fisheries products

- ⦁ Topic 4: Education

- ⦁ Topic 5: Defense

- ⦁ Topic 6: Meeting Proceeding

- ⦁ Topic 7: Determination and resolution (procedure)

- ⦁ Topic 8: North Korean Issue

- ⦁ Topic 9: Budget planning and execution

- ⦁ Topic 10: Prosecutor

- ⦁ Topic 15: Meeting progress statement

- ⦁ Topic 16: Secret heavyweight and government secretary (Park Geun-hye era)

- ⦁ Topic 17: Confirmation hearings and espionage cases

- ⦁ Topic 18: Household debt

- ⦁ Topic 19: Committee Staff

- ⦁ Topic 20: Railway strikes, Labor Union, and Energy Supply

- ⦁ Topic 21: Argument and conflict

The nominal topics related to meeting progress include Topics 1, 6, 7, 12, 15, and 19, while the remaining topics are specific to individual committees.

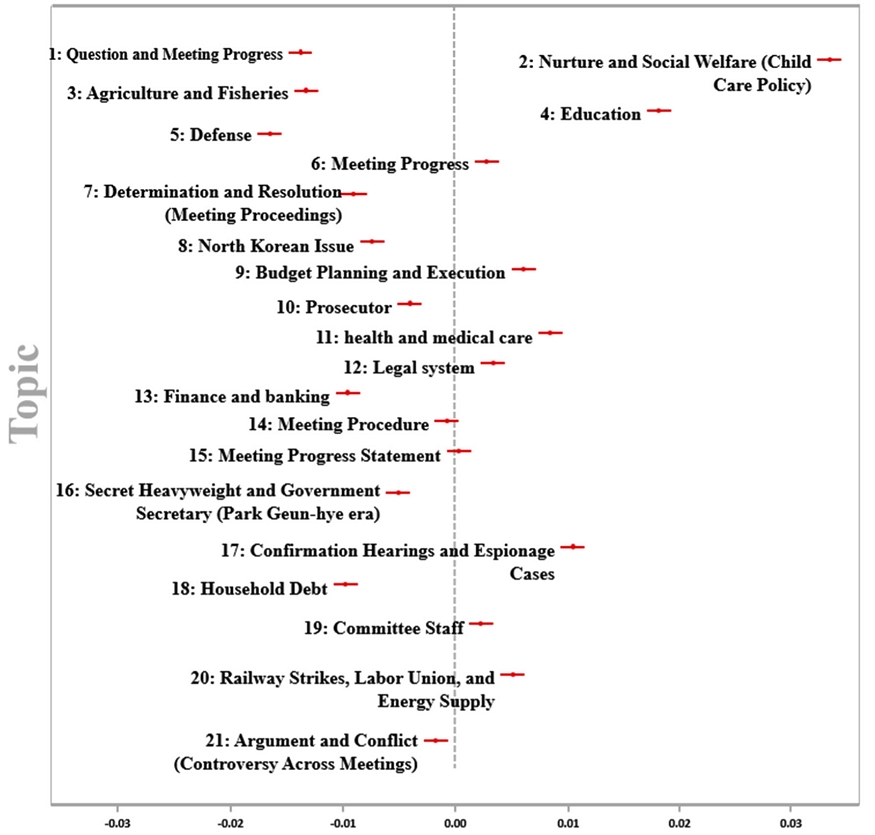

Figure 2 visualizes the 95% confidence intervals, estimating the effects of gender on expected topic proportions. Our analysis reveals distinct patterns of engagement across different topics. Female legislators showed significantly higher levels of engagement in several areas: Topics 2 (nurture and social welfare), 4 (education), 17 (confirmation hearings), 11 (health and medical care), 9 (budget planning and execution), 20 (railway strikes and labor unions), and 6 (meeting proceeding). Among these, the strongest effects were observed in Topics 2 and 4, where women’s speeches were approximately 3% and 2% more frequent than men’s, respectively.

In contrast, male legislators showed higher levels of participation in Topics 5 (defense), 1 (question and meeting progress), 18 (household debt), 13 (finance and banking), 7 (determination and resolution), 8 (North Korean issue), 16 (secret heavyweight), and 10 (prosecutor). The most pronounced male dominance was observed in Topic 5 (defense), where men’s speeches were about 1.5% more frequent.

Some topics, such as Topics 15 (meeting progress statement) and 19 (committee staff), showed no significant gender differences in speech frequency.

Among the 21 topics identified from the 19th National Assembly’s standing committee minutes, Topic 2 (nurture and welfare), Topic 4 (education), and Topic 11 (health and medical care) were especially prominent for female lawmakers. In these topics, the proportion of remarks made by female lawmakers is noticeably higher compared to their male counterparts.

Topic 2 (nurture and welfare) includes keywords such as childcare, daycare centers, children, single mothers, childbirth, and women. Our analysis shows that female lawmakers made significantly more remarks on this topic, with approximately 3% higher frequency compared to male lawmakers. The discussions focused on strengthening public childcare services and securing funding for free childcare programs to address low birth rates and reduce the economic burden on families. This finding confirms the consistent pattern observed in our data, where female legislators demonstrate particularly strong engagement in issues directly affecting women and children. These issues have traditionally been seen as “women-friendly,” and female lawmakers appear to be leading these discussions during the standing committee deliberations, reflecting their role as substantive representatives of women’s interests.

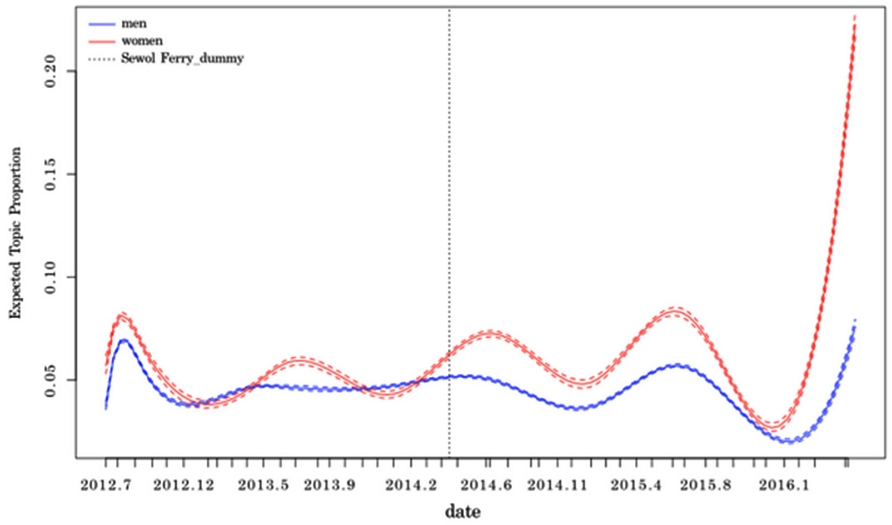

Changes in Topic Prevalence Over Time: Topic 2 (Nurture and Social Welfare) and Topic 4 (Education).*Prevalence of Topic plotted as a smooth function of date, with the rate held at the sample median and 95% confidence intervals.

Topic 4 (education) is characterized by keywords such as private, parents, elementary schools, national universities, and public education. Female lawmakers spoke about 2% more on this topic compared to their male colleagues. In the 19th National Assembly, active debates took place around bills aimed at improving public education, such as a special bill on regulating private tutoring and promoting the normalization of public education. While there was broad agreement on the need to strengthen history education, politically charged issues like the nationalization of history textbooks and their role in the College Scholastic Ability Test were also key topics. However, discussions around providing universal free education, particularly for high school students, seemed to be a greater focus for female lawmakers.

Analysis of their remarks shows that women legislators were more engaged in discussions around public education reform and universal free education, rather than the more politically sensitive issue of history textbooks. This aligns with previous research showing that women lawmakers tend to prioritize education-related issues and exhibit different legislative behaviors in this area.

Historically, education has been viewed as a key women’s interest in South Korea due to the cultural expectation that women serve as primary caregivers and educators within the family. Female lawmakers’ involvement in educational policy reflects their concern for issues directly impacting family well-being, particularly in areas like early childhood education and the broader social mobility that education provides (Park & Jin, 2017). Thus, education policy is not only about academic content but also about creating support systems that help women balance work and family life, reinforcing the idea that education is a core women’s interest.

Topic 11 (Health and medical care) also attracted a higher number of comments from female lawmakers during the 19th National Assembly. This topic includes keywords such as disinfectants, fires, toxicity, humidifiers, viruses, deaths, and draft dodgers, indicating that discussions often centered on the issue of humidifier disinfectants. Many children lost their lives due to the toxic effects of these disinfectants, prompting numerous fact-finding meetings and follow-up measures, which were predominantly led by female lawmakers.

Analysis of Topic 11 shows that female legislators were particularly active in addressing safety concerns, such as the outbreaks of MERS, Ebola hemorrhagic fever, and the spread of infections, taking a leadership role in these discussions during standing committee meetings.

A notable trend in Topic 11 is the shift in the volume of remarks made by female lawmakers before and after the Sewol ferry disaster. Before the incident, the number of comments made by female and male lawmakers on this topic was relatively similar. However, after the Sewol ferry disaster, the number of remarks by female lawmakers increased significantly compared to their male counterparts. The tragedy, which claimed the lives of many students, shocked the nation and brought greater attention to child safety issues. Female lawmakers appeared to be especially sensitive to matters of child safety, such as the health risks posed by humidifier disinfectants and the spread of infectious diseases.

Analysis of Topic 12 (Legal system) reveals an interesting pattern of female legislators’ engagement with legislative procedures and legal frameworks. Keywords in this topic include “revise,” “subsidiary law,” “presidential decree,” “special rule,” “bill,” “Special Act,” and “civil law.” Female lawmakers showed notably higher participation in discussions related to legal system reforms and legislative procedures. This finding is particularly significant as it demonstrates women legislators’ active involvement in shaping the fundamental structures of governance, moving beyond policy-specific discussions to engage with broader institutional frameworks. Their higher engagement in legal system discussions may reflect their growing institutional expertise and their commitment to ensuring proper legislative procedures, particularly in areas affecting women’s rights and social welfare.

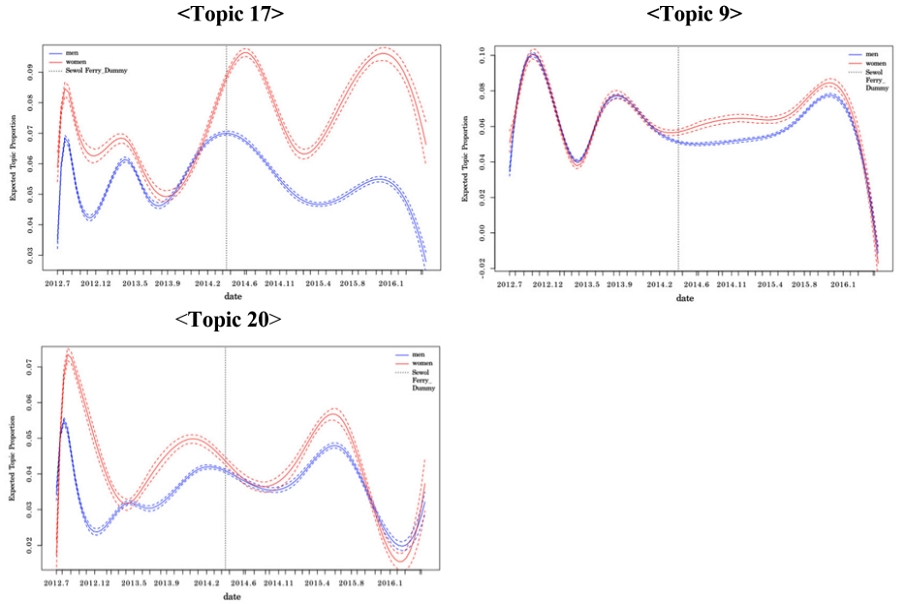

Although these topics are not directly related to the typical women’s agenda, female lawmakers made a higher percentage of remarks on Topic 17 (confirmation hearings), Topic 9 (Budget planning and execution), and Topic 20 (railway strikes and labor union, energy supply), excluding areas related to meeting progress.

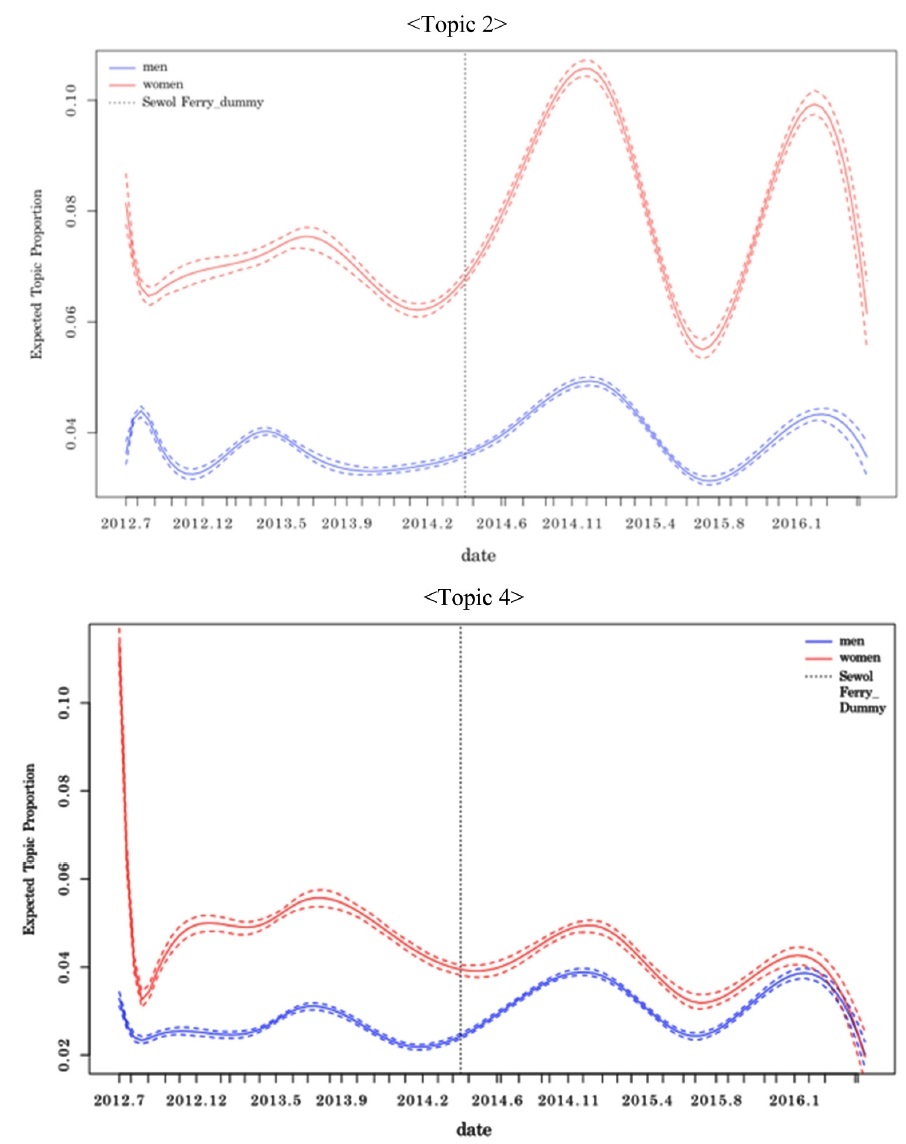

Changes in Topic Prevalence Across Key Policy Areas — Confirmation Hearings, Budget Execution, and Railway Strikes.*This figure illustrates shifts in the prevalence of remarks within Topic 17 (Confirmation Hearings), Topic 9 (Budget Planning and Execution), and Topic 20 (Railway Strikes, Labor Unions, and Energy Supply).

Topic 17 includes keywords such as evidence, spouse, reporter, and identity, reflecting discussions around confirmation hearings for public officials, such as ministers and prosecutors. These remarks, often from female opposition party members, focused on allegations like evasion of gift taxes, plagiarism, and military service dodging during confirmation hearings. In Korea, confirmation hearings are conducted by special committees for high-ranking positions like the Prime Minister and Chief Justice, while ministerial candidates are reviewed by standing committees. Female lawmakers were particularly active in these hearings, a finding not commonly observed in prior studies, which typically focused on bill proposals and voting behavior. This highlights the significant role female lawmakers play in executive supervision through confirmation hearings, an area previously underexplored.

Topic 9 relates to budget and accounting, with keywords such as reduction, main budget, carryover, and budget execution rate. Female lawmakers frequently addressed issues like discrepancies between budget carryovers and increased budget requests for the following year. Their remarks often highlighted inefficiencies in the budgeting and execution processes, and they meticulously examined whether budget proposals were necessary or whether supplementary budgets were justified. This finding was unexpected, as women lawmakers were more actively involved in budget and settlement deliberations than anticipated. Previous studies have highlighted women’s roles in local governance (Lee, 2020), but their significant contribution to national budget oversight adds an important dimension to their legislative role.

Topic 20 covers issues related to the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, and Transport, Korea Electric Power Corporation, and Korea Water Resources Corporation, with keywords such as railway, water resources, power generators, and airports. One notable issue was the debate over the introduction of a railway competition system, a key government initiative to develop the railway industry, which faced strong opposition. Additionally, there were ongoing disputes at the Environment and Labor Committee over labor union suppression through corporate closures, as well as debates on nuclear waste disposal and thermal power management within the framework of a national energy plan. Female lawmakers demonstrated a strong interest in labor union issues, particularly regarding strikes related to railway privatization and corporate shutdowns. Their remarks revealed a deep concern for socially disadvantaged groups, such as labor unions, highlighting their broader commitment to social justice issues.

These results help resolve the controversy surrounding the capabilities of female lawmakers. In particular, even those elected through the female quota system are not mere “tokens” or “proxy women,” but active representatives working to protect women’s interests. Our analysis of the KNA minutes confirmed that, as shown in previous studies, women were more active than men in deliberating women-friendly issues.

Topic 20, which includes discussions on labor rights and union repression, might initially seem unrelated to gender. However, when viewed through a gendered lens, labor rights become a critical issue for women, particularly in sectors where they are overrepresented, such as service industries and care work. These sectors often involve precarious working conditions, wage inequality, and limited access to social protections (Kim & Lee, 2024). Female lawmakers’ involvement in these debates can thus be seen as part of a broader effort to improve working conditions for women and address systemic gender inequalities in the labor market.

Moreover, the analysis confirmed that women are more actively involved than men in deliberating safety and labor issues, which have traditionally received less attention. Additionally, women took on leadership roles in areas that could not be fully captured by aggregate data, such as bill initiation rates, approval rates, and votes in plenary sessions. In other words, women were actively engaged in key administrative oversight functions, such as confirmation hearings and budget deliberations, areas where their contributions have not been fully recognized by traditional metrics.

The analysis of standing committee deliberations provides strong empirical support for our hypotheses. First, female legislators demonstrated significantly higher engagement in traditionally defined women’s issues (H1). Their active participation in Topics 2 (nurture and welfare), 4 (education), and 11 (health and medical care) shows that women legislators continue to serve as substantive representatives for women’s interests. The finding that women made approximately 3% more remarks on childcare and welfare issues, and 2% more on education, quantitatively supports this hypothesis.

Second, our analysis confirms that female legislators have expanded their influence beyond traditionally gendered policy domains (H2). Their significant engagement in Topics 17 (confirmation hearings), 9 (budget planning), and 20 (railway strikes and labor issues) demonstrates that women legislators are actively participating in broader institutional oversight and policy formation. This finding is particularly significant as it challenges conventional assumptions about women legislators’ policy focus and suggests their growing influence in core legislative functions.

Third, the temporal analysis reveals meaningful variations in women’s legislative engagement patterns (H3). Particularly notable is the shift in participation following the Sewol ferry disaster, where female legislators significantly increased their involvement in Topic 11 (health and medical care), demonstrating their responsive adaptation to emerging social issues. This temporal variation reflects the dynamic nature of substantive representation and women legislators’ capacity to adapt their focus according to changing social needs.

Theoretical Justification for Women’s Broader Engagement in Policy Areas

In the context of the KNA, the proactive engagement of female lawmakers in both gender-specific and broader policy areas can be understood through the lens of critical actor theory (Celis et al., 2008). Female legislators, particularly those elected via proportional representation, often have the flexibility to focus on overarching national concerns rather than district-specific issues. This institutional dynamic enables them to lead deliberations on topics like budget and labor union policies, which are crucial for addressing structural inequalities impacting all citizens. Moreover, global trends suggest that as women’s descriptive representation increases, their participation expands beyond traditional “women’s issues” to include areas like economic reform, labor rights, and governance (Franceschet & Piscopo, 2008; Krook & Zetterberg, 2016; Wang, 2014).

South Korea’s unique sociopolitical landscape further underscores this trend. The implementation of gender quotas and the increasing salience of gender issues in public discourse, catalyzed by events such as the Sewol ferry disaster and labor union controversies, have heightened the expectation for female lawmakers to address systemic societal challenges. As such, women legislators are not only advocates for gender equality but also key actors in shaping broader legislative priorities, reflecting the evolving role of women in political representation.

These dynamics align with recent findings in East Asian contexts, where women legislators have expanded their influence beyond traditional domains. For instance, Joshi & Echle (2023) and Huang (2016) observed similar patterns in Japan and Taiwan, respectively, where female lawmakers have played active roles in economic and labor policy deliberations. These examples highlight how the interaction of institutional factors, cultural norms, and individual agency enables female legislators to redefine the scope of substantive representation. In the Korean National Assembly, this expansion of women’s legislative engagement underscores the importance of analyzing both gender-specific and broader policy contributions.

Conclusion: Beyond Substantive Representation

The underrepresentation of women in legislative bodies has been a longstanding concern, and much debate has focused on whether female lawmakers truly represent women’s interests. However, many prior studies have limited their analysis to legislative proposals, overlooking the broader scope of parliamentary activities. To address this gap, our study analyzed the minutes of 23 standing committees during the 19th National Assembly, examining approximately one million comments. Through this analysis, we identified 21 topics based on recurring keywords and calculated the percentage of remarks made by male and female lawmakers.

Our findings show that female lawmakers were significantly more active in discussing topics related to women’s interests, such as childcare and social welfare (Topic 2), education (Topic 4), and health and medical care (Topic 11). Importantly, these results align with previous research that has focused on bill proposals and approval rates, but we extend this by confirming that women also take a leading role in the deliberative process within standing committees.

Moreover, even in areas not traditionally linked to women’s issues, such as confirmation hearings (Topic 17), budget and settlement (Topic 9), and railway strikes and infrastructure (Topic 20), female lawmakers made a significant impact. Topic 20, in particular, involves labor rights and union repression, areas that might initially seem unrelated to gender. However, when viewed through a gendered lens, labor rights become a critical issue for women, especially in sectors where they are overrepresented, such as service industries and care work. These sectors often face precarious working conditions, wage inequality, and limited access to social protections (Kim & Lee, 2024). Female lawmakers’ involvement in these debates reflects a broader effort to address systemic gender inequalities in the labor market, underscoring their role in improving working conditions for women.

The analysis also confirmed that women were more actively involved than men in deliberating safety and labor issues, which have traditionally received less attention. Female lawmakers took on leadership roles in areas that could not be fully captured by aggregate metrics like bill initiation rates or votes in plenary sessions. In particular, their contributions to key administrative oversight functions, such as confirmation hearings and budget deliberations, highlight their importance in shaping legislative processes beyond traditional women’s issues.

Our study reveals that female lawmakers in the 19th National Assembly were not only advocates for women’s agendas but also meticulous in their oversight functions, such as budget reviews and confirmation hearings. Furthermore, despite women making up only 15.67% of the National Assembly, they played a substantial role in a wide range of topics, indicating that female legislators contribute meaningfully beyond the scope of traditional gender issues.

These results help resolve the controversy surrounding the capabilities of female lawmakers. Women elected through the quota system are not merely “tokens” or “proxy women,” but active representatives working to protect and promote women’s interests. Their engagement in a broad array of issues challenges assumptions about their political limitations and highlights their influence across policy domains.

Looking ahead, these findings have significant implications for the future of gender representation in South Korea. As female lawmakers continue to assert their influence in a range of policy areas, including those traditionally dominated by men, this could pave the way for more substantive representation in fields like defense, finance, and foreign policy—areas where women have historically been underrepresented. The growing presence and active participation of women in these broader policy areas suggest that gender quotas and increased descriptive representation can lead to tangible changes in legislative priorities.

If this trend continues, future legislative bodies may see an even more pronounced shift in gender dynamics, with female lawmakers playing critical roles in shaping policies across the political spectrum. This expansion of women’s political engagement could contribute to breaking down barriers in male-dominated policy areas, thus fostering more inclusive and equitable policymaking.

In the long term, the increased involvement of women in legislative deliberation may contribute not only to better representation of women’s interests but also to the overall democratization of legislative processes. The role of female lawmakers in administrative oversight and budgetary control suggests a future where women are not just participants but key decision-makers in South Korea’s political landscape. As the 20th National Assembly and beyond continue to evolve, this growing trend of gender representation holds the potential to enhance both descriptive and substantive representation, advancing gender equality and improving the quality of democratic governance in South Korea.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported by Konkuk University in 2024.

References

-

Blei, D. M., & Lafferty, J. D. (2007). A correlated topic model of science. The Annals of Applied Statistics, 1(1), 17–35.

[https://doi.org/10.1214/07-aoas114]

-

Blei, D. M., Ng, A. Y., & Jordan, M. I. (2003). Latent dirichlet allocation. Journal of machine Learning research, 3(Jan), 993–1022.

[https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/1120.003.0082]

-

Celis, K. (2008). Gendering representation. Politics, Gender, and Concepts: theory and methodology, 71–93.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511755910.004]

-

Celis, K., Childs, S., Kantola, J., & Krook, M. L. (2014). Constituting women’s interests through representative claims. Politics & Gender, 10(2), 149–174.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X14000018]

- Davidson, Roger H. & Walter J. Oleszek. (2008). Congress and Its Members. Washington, DC: CQ Press.

-

Dolan, K., & Ford, L. E. (1995). Women in the state legislatures: Feminist identity and legislative behaviors. American Politics Quarterly, 23(1), 96–108.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673x9502300105]

-

Franceschet, S., & Piscopo, J. M. (2008). Gender quotas and women’s substantive representation: Lessons from Argentina. Politics & Gender, 4(3), 393–425.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/s1743923x08000342]

-

Huang, C. L. (2016). Reserved for whom? The electoral impact of gender quotas in Taiwan. Pacific Affairs, 89(2), 325–343.

[https://doi.org/10.5509/2016892325]

- Jeon, J. (2009). Are women members more likely to vote for women’s issue bills?: An analysis of members` voting behavior. Journal of Legislative Studies, 28, 187–218. (In Korean) UCI: I410-ECN-0102-2012-340-000882704

- Jeong, M., & Lee, H.-W. (2020). Do Female representatives represent females? The evidence from 19th National Assembly of the Republic of Korea. Journal of Legislative Studies, 59, 64–103. (In Korean)

-

Joshi, D. K., & Echle, C. (2023). Substantive representation of women in Asian parliaments. London: Taylor & Francis.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003275961]

- Kim, M. (2011). The Gender Difference in Policy Priorities of South Korean Legislators. Journal of Korean Politics, 20(3), 109–136. (In Korean)

-

Kim, T., & Lee, S. S. Y. (2024). Double poverty: class, employment type, gender and time poor precarious workers in the South Korean Service Economy. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 54(3), 412–431.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2023.2176782]

-

Krook, M. L., & Zetterberg, P. (2016). Gender Quotas and Women's Representation: New Directions in Research. London: Routledge.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315695075]

-

Kweon, Y., & Ryan, J. M. (2022). Electoral systems and the substantive representation of marginalized groups: evidence from women’s issue bills in South Korea. Political Research Quarterly, 75(4), 1065–1078.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/10659129211028290]

-

Lee, A. R., & Lee, H. -C. (2013). The Women’s movement in South Korea revisited. Asian Affairs: An American Review, 40(2), 43–66.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00927678.2013.788412]

-

Lee, A.-R., & Lee, H.-C. (2020). Women representing women: The case of South Korea. Korea Observer, 51(3), 437–462.

[https://doi.org/10.29152/koiks.2020.51.3.437]

-

Lee, H.-C. (2018). Silver generation’s counter-movement in the information age: Korea’s pro-Park rallies. Korea Observer, 49(3), 465–91.

[https://doi.org/10.29152/koiks.2018.49.3.465]

-

Li, X., Zhao, X., Fu, Y., & Liu, Y. (2010). Bimodal gender recognition from face and fingerprint. In 2010 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2590–2597. IEEE.

[https://doi.org/10.1109/cvpr.2010.5539969]

-

Liu, A. (2018). Gender quotas and political representation in South Korea: Impacts on women’s legislative behavior. Korean Journal of Policy Studies, 33(1), 45–65.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/KJPS-2018-45]

-

Mansbridge, J. (1999). Should blacks represent blacks and women represent women? A contingent “yes”. The Journal of Politics, 61(3), 628–657.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/2647821]

-

Mimno, D. & Lee, M. (2014). Low-dimensional embeddings for interpretable anchor-ba Voting behavior of women legislators on women-related bills - Focus on the Gender equality bills in the 17th, 18th, and 19th National Assembly sed topic inference. In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP). 1319–1328.

[https://doi.org/10.3115/v1/D14-1138]

- Mimno, D., Wallach, H., Talley, E., Leenders, M., & McCallum, A. (2011). Optimizing semantic coherence in topic models. In Proceedings of the 2011 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. 262– 272.

-

Park, S. & Jin, Y. (2017). Voting behavior of women legislators on women-related bills - Focus on the Gender equality bills in the 17th, 18th, and 19th National Assembly, The 21st Century Political Science Review, 27(2), 111–136. (In Korean)

[https://doi.org/10.17937/topsr.27.2.201706.111]

-

Piscopo, J. M. (2011). Rethinking descriptive representation: Rendering women in legislative debates. Parliamentary Affairs, 64(3), 448–472.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsq061]

- Pitkin, H. F. (1967). The concept of representation. University of California Press.

- Reingold, B. (2003). Representing women: Sex, gender, and legislative behavior in Arizona and California. Univ of North Carolina Press.

-

Roberts, M. E., Stewart, B. M., & Airoldi, E. M. (2016). A model of text for experimentation in the social sciences. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 111(515), 988–1003.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.2016.1141684]

- Roberts, M. E., Stewart, B. M., Tingley, D., Airoldi, E. M., & et al. (2013). The structural topic model and applied social science. Paper presented at the Advances in neural information processing systems workshop on topic models: computation, application, and evaluation, Vol. 4. Harrahs and Harveys, Lake Tahoe. 1–4.

-

Roberts, M. E., Stewart, B. M., Tingley, D., & et al. (2014). stm: R package for structural topic models. Journal of Statistical Software, 10(2), 1–40.

[https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v091.i02]

-

Schwindt‐Bayer, L. A. (2006). Still supermadres? Gender and the policy priorities of Latin American legislators. American Journal of Political Science, 50(3), 570–585.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00202.x]

- Seo, B.-K. (2010). The comparative analysis of women members' bills in 17-18th Korea National Assembly. Journal of Women's Research, 8, 33–60. (In Korean)

-

Shim, J. (2021). Gender and Politics in Northeast Asia: Legislative Patterns and Substantive Representation in Korea and Taiwan. Journal of Women, Politics & Policy, 42(2), 138–155.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/1554477X.2021.1888677]

-

Shin, K. Y. (2023). Substantive Representation of Women in South Korea's National Legislature. In Joshi, D. K. & C. Echle (Eds.). Substantive Representation of Women in Asian Parliaments (pp. 50-69). London: Routledge.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003275961-4]

- Vogel, A., & Jurafsky, D. (2012, July). He said, she said: Gender in the ACL anthology. In Proceedings of the ACL-2012 Special Workshop on Rediscovering 50 Years of Discoveries. Jeju Island, Korea. 33–41.

-

Wallach, H. M., Murray, I., Salakhutdinov, R., & Mimno, D. (2009). Evaluation methods for topic models. In Proceedings of the 26th annual international conference on machine learning. Montreal Canada. 1105–1112.

[https://doi.org/10.1145/1553374.1553515]

-

Wang, V. (2014). Tracing gender differences in parliamentary debates: A growth curve analysis of ugandan MPS’ activity levels in plenary sessions, 1998–2008. Representation, 50(3), 365–377.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00344893.2014.951234]

-

Wang, Y.-C., Burke, M., & Kraut, R. E. (2013). Gender, topic, and audience response: an analysis of user-generated content on facebook. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Paris, France. 31–34.

[https://doi.org/10.1145/2470654.2470659]

Biographical Note: Hyun-Chool Lee is Professor at the Political Science Department of Konkuk University, Seoul, South Korea. He completed a Ph.D. specializing in Comparative politics at Konkuk University. He served as Council of Politics and Administration Office in the National Assembly Research Service from 2003 to 2015. His main research area is Political Process, Korean Politics, Social Movement, Gender Politics and Population Aging. E-mail: lhc0609 @konkuk.ac.kr

Biographical Note: Eun Kyung Kim is Assistant Professor at the Political Science Department of Konkuk University, Seoul, South Korea. She completed a Ph.D. specializing in Comparative Politics at Konkuk University. Her main research areas include Political Process, Political Inequality, and Local Governance E-mail: tellme@konkuk.ac.kr

Biographical Note: Jae Ho Chang is Ph.D. student at Department of Statistics College of Arts and Sciences, the Ohio State University. His research interests include high dimensional data analysis. E-mail: chang.2090@osu.edu