Visual Representation of Gender in English Language Textbooks of Bangladesh and Teachers’ Voices

Abstract

Textbooks play a crucial role in shaping young learners’ perceptions of gender roles and equality. Researchers worldwide highlighted the impact of gender representation in school textbooks through visual imagery to develop the mindset of the school children. Therefore, this study focused on examining the visual images and illustrations in primary education textbooks in Bangladesh. Alongside, it explored the perceptions of the teachers as they directly explain the textual materials to the learners. It employed Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) as the framework for data analysis. Applying a mixed-methods approach, the study investigated the English language textbooks for Classes I to V to examine visual representation of gender using the content analysis method. Findings revealed that female characters, in comparison to male characters, were underrepresented through visuals. Men enjoyed supremacy and were highlighted in sports and outdoor activities, unlike women. Such representation demonstrated the stereotypical social construction of gender and patriarchal oppression. Most importantly, primary school teachers recognized the unequal gender representation and emphasized the need for textbooks to reflect gender equality, as visual content can deeply influence young learners’ expectations and self-perception. Therefore, the study suggested reviewing and updating the existing textbooks for equal visualization of gender.

Keywords:

Gender equality, textbooks, visual representation, social construction, patriarchal oppressionIntroduction

Textbooks are considered the most accessible resource for learning for young learners. They play a vital role in socialisation or transmission of knowledge or values (Curaming & Curaming, 2020). There are various aspects that a textbook can evaluate (Sovič & Hus, 2016). Curriculum developers have emphasized the importance of assessing and adjusting content to align with the requirements of students (Brown, 2000; Tomlinson, 2012). Nevertheless, visual analysis is referred to as highly significant for the EFL textbooks by numerous researchers since visuals help learners clarify the concepts of the textbooks. “Semiotics in illustration are very specific element especially because they have great influence on children’s visual perception” (Sovič & Hus, 2016, p. 639). Thus, visualization helps formulate the perceptions of the learners. Hence, several research studies explored the significance of visual representation of gender in school textbooks since less visibility of one gender adheres to discrimination. The visual imbalance between females and males might distort the values of young learners, as visual discourse along with written discourse works as a significant tool for successful communication (Giaschi, 2000). “Much meaning is conveyed through images, photos, cartoons and illustrations, any visual misrepresentation of females and males might spoil the bias-free texts or distort the high values preached to students in the course of their learning experiences” (Khalid & Ghania, 2019, p. 774). Therefore, the present study analyzed gender positioning in the visual discourse in textbooks.

The study examines the English for Today (EfT) textbooks used at the primary level of education in Bangladesh, which are published and distributed by the National Curriculum and Textbook Board (NCTB) for the academic year 2023. Primary education serves as the foundation of a child’s academic journey and plays a crucial role in shaping cognitive, linguistic, and social development. In Bangladesh, primary education spans from Class I to Class V, covering subjects such as Bangla, English, mathematics, science, social studies, religion and moral education, and physical education. Among these, English holds a distinctive position due to its role as a global lingua franca and its perceived value in shaping students' future opportunities. Moreover, EfT textbooks are the only government-approved English textbooks for primary education, they are highly representative of the broader educational context in Bangladesh.

Proficiency in English is widely regarded as a key determinant of social and economic mobility in Bangladesh, as it enhances access to higher education, employment opportunities, and international communication (Nur et al., 2021). Given this significance, English language textbooks serve not only as linguistic tools but also as socio-cultural artifacts that influence students’ perceptions of the world, including gender roles and identities. Prior research has emphasized that language textbooks play a critical role in promoting or challenging gender stereotypes. For example, Isnaini et al. (2019) highlighted that English textbooks contribute to the development of intercultural competence, reinforcing or challenging existing social norms, including those related to gender.

Despite growing awareness of gender equality in educational materials, studies have shown that gender biases persist in many English language textbooks worldwide. In the context of Bangladesh, where gender disparities remain a pressing issue in various social and economic spheres, it is crucial to examine whether textbooks perpetuate or challenge traditional gender norms. Women in Bangladesh have made significant strides in education, employment, and political participation over the years. According to the Ministry of Planning (2022), the literacy rate for females was 74.7% in 2022, reflecting improvements in educational attainment. However, disparities persist in labor force participation, with only 42.7% of women engaged in the workforce compared to 81.7% of men (Ministry of Planning, 2022). Nevertheless, gender gaps remain evident in leadership roles and wages, indicating continued societal challenges in Bangladesh. These inequalities often stem from deeply embedded cultural norms and are reinforced through various socialization agents, including textbooks. Therefore, it is imperative to analyze whether educational materials support gender equity or perpetuate stereotypes that hinder progress toward gender equality.

Hence, this study investigated the visual representation of gender in primary-level English for Today textbooks, analyzing how male and female figures are portrayed in images. Additionally, it incorporates teachers’ perspectives to gain insights into how these representations influence classroom discourse and student perceptions. The study is guided by the following research questions:

- i) How do the textbooks visually construct gender representation?

- ii) How do teachers perceive the visual representation of gender?

- iii) What do the teachers think of promoting gender equality in the textbooks?

Visual Representation of Gender in Textbooks

Existing literature exposed the significance of visuals in textbooks. Ghoushchi et al. (2021) revealed a close nexus between texts and images. In their study, Ghoushchi et al. (2021) revealed that pictures can convey meanings more than words. They added that detailed information can be conveyed easily and quickly through visuals. They further mentioned that “using visuals in teaching results in a greater degree of learning” (p. 624). Moreover, equal visibility of both genders is crucial as an uneven representation of gender can spread in society through textbooks (Bahman & Rahimi, 2010).

They argued that pictures can convey information and meaning more competently and effectively, especially to EFL learners. Hence, discrepancies in symbols, gestures, and actions may convey biased messages to the learners regarding gender roles in society.

In terms of visual representation of gender in textbooks, equality was not maintained in many cases. While less visibility of women was noticed in the textbooks in 1978 by Hartman and Judd, similar findings were explored by Khalid and Ghania in 2019. Discrimination in male-female visibility was considered one of the extensively examined demonstrations of gender discrepancy by Li (2016). In her study, Li revealed male dominance in visual discourses and stated that “images in different illustrations can be regarded as examples of segregation” (Li, 2016, p. 483). She directed a visual content analysis of 1800 characters in two sets of elementary language textbooks in her study. The textbooks were used during the 1980s and the 2000s in China. She advocated for gender-balanced illustrations in textbooks developing the mindset of young learners.

Earlier, Hartman and Judd (1978) also exposed that in several texts women suffered from low visibility. They analyzed the ESL textbooks and found that in maximum cases male referents profoundly outnumbered females. The ratio of male to female referents was found to be 63%–37% in the study of Hartman and Judd. They also revealed a scarcity of women characters in reading texts. In reading passages, male characters became visible more frequently than female characters.

The visual discrepancy was also traced in Pakistani textbooks by Ullah and Skelton (2013). In their study, Ullah and Skelton pointed out that the number of boys or men in the images and illustrations was higher than that of girls or women. For instance, they found 1220 male characters and only 632 female characters in the illustrations of the Pakistani school textbooks. Besides, males were also depicted in a wider range of sports activities in those textbooks. The analysis of the images and texts of those books showed male dominance in sports. Ullah and Skelton explored that in terms of frequency, male characters were overrepresented in sports (in 85 items) whereas female characters were observed only in 17 items in a very narrow range of sports. For example, boys were portrayed in a wide range of sports such as badminton, basketball, football, cricket, hockey, horse riding, volleyball, and swimming. In contrast, girls were portrayed in a narrow range such as swinging, skipping, and playing with dolls.

Khalid and Ghania (2019) conducted a study investigating gender visibility in Algerian English textbooks, particularly focusing on the portrayal of women. Using a qualitative approach and Giaschi’s (2000) critical image analysis framework, the researchers examined three key categories: productive versus reproductive professions, sports and activities, and frequency of appearances. The findings revealed a biased and partial depiction of female characters in the illustrations, where males were consistently portrayed as dynamic protagonists, reinforcing men’s societal authority. In contrast, women were often assigned inactive and submissive roles, with lower status in the images.

The study emphasized the analysis of body language, and gaze direction. While both genders were depicted with confidence, men were portrayed as courageous in adversity, while women were shown as emotionally overwhelmed and unable to control their reactions to disasters. The researchers also noted inconsistencies in the gaze direction, with men displaying self-assurance and affirmation, while some women expressed fear and distress.

The visual representations highlighted significant disparities against female characters, with women notably absent from outdoor works and activities. Khalid and Ghania (2019) concluded that such unequal portrayals contribute to the dominance of men, potentially influencing negative perceptions among learners, especially females. The researchers cautioned that biased educational materials might hinder girls’ achievements by challenging their identities and deterring them from pursuing their goals. Nevertheless, these findings are crucial since visual images are significantly important to comprehending the meanings of textbooks for young learners (Ghoushchi et al., 2021).

Teachers’ Perceptions Regarding Visual Representation of Gender in textbooks

Numerous research studies have explored the connection between teachers’ explanations and students’ understanding, with a focus on global perceptions of gender representation in textbooks. The exploration indicates that gender-equitable examples in textbooks can inspire girls to shape their professional and societal roles, while gender segregation may perpetuate female subjugation.

A study by Tainio and Karvonen (2015) in Finland, known for its commitment to gender equality, revealed gender bias in school textbooks. The investigation covered English, Mathematics, and vocational guidance textbooks, examining content and visuals across different grade levels. Through conversation analysis of video-recorded discussions among teachers, the study unveiled prevalent gender stereotypes. Despite Finland’s reputation for gender equality, the analysis exposed discrepancies in visual representations and discriminations in the number of images depicting female and male characters. The findings prompted Finnish teachers to advocate for neutral conceptions of gender and sexuality in textbooks.

In contrast, Algerian teachers, as observed by Khalid and Ghania (2019), displayed differing opinions on gender representation. Despite positive teacher perceptions regarding gender balance in illustrations and visual discourses in Algerian textbooks, content analysis revealed widespread discrimination against females. The study, involving 25 teachers, uncovered a lack of awareness of gender equality among educators. The mismatch between teachers’ perceptions and content analysis raised concerns about the peripheral consideration of gender bias in EFL language education.

Overall, the exploration of the link between teachers’ explanations and students’ understanding highlights the global issue of gender representation in textbooks. Finnish teachers acknowledge and address gender bias, urging for neutral representations, while Algerian teachers, despite positive perceptions, unknowingly contribute to gender discrimination in their classrooms. The discrepancy between teacher awareness and content analysis underscores the need for increased attention to gender bias in educational materials.

Discrimination based on gender was also explored by Bangladeshi school teachers. Hossain (2018) exposed teachers’ perceptions regarding gender stereotyping in ELT textbooks. However, Hossain (2018) worked on the perceptions of teachers of some prominent English Medium Schools in Dhaka city. Nevertheless, the perceptions of the teachers of government primary schools were not focused on her study.

Based on existing research, this section explored that gender biases are observable through visuals in various countries. The section also indicated that teachers across the world also traced gender bias in the textbooks and suggested including gender-equitable textbooks in the school curriculum. However, no substantial research was done regarding gender discrimination in textbooks in Bangladesh, especially for the primary level of education. Primary School teachers’ perceptions were also not explored.

Thus, the current study investigated the visual representation of gender in English language textbooks. Alongside, the perceptions of teachers from rural and urban government primary schools were examined to understand how contextual factors shape their views on the visual representation of gender in English language textbooks. The key differences between these two groups stem from their socio-cultural backgrounds, exposure to diverse learning environments, and the resources available in their respective schools. Teachers in urban areas often have access to a more diverse student population, greater professional development opportunities, and a wider range of teaching materials. In contrast, rural teachers may work in settings with more traditional gender norms, limited access to supplementary materials, and fewer professional training opportunities that address gender sensitivity in education. These factors contribute to potential variations in their perceptions of gender representation in textbooks.

The focus on teachers in government primary schools is particularly significant because these schools serve the majority of students in Bangladesh, especially those from underprivileged backgrounds. As government textbooks are the primary learning materials in these schools, teachers play a crucial role in mediating the content and influencing students’ understanding of gender roles. Examining their perspectives provided valuable insights into how gender representations in textbooks were interpreted and reinforced in the classroom. Moreover, understanding their views can inform future textbook revisions and teacher training programs to promote more equitable gender representation in primary education.

Theoretical Construct

The study traced Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) as a theoretical lens. CDA has been widely applied by feminists to do a critical examination of gender. Feminism which has inspired gender and language studies deals with the notion of power and looks for a balance of power through mitigating domination (Sunderland, 2006; Shrewsbury, 1987). Gender and power are also connected to social context. CDA is based on the idea that all discourse is deeply linked to social structures and power dynamics (Chun, 2024). The traditional concept of ‘power’ systematically oppresses women (Narayan, 2004). Thus, women’s and knowledge are ignored in a patriarchal society. In her study on feminist epistemology, Narayan (2004) mentioned that the contribution of women has been distorted as inferior and secondary to that of men. Such a biased notion is often represented in discourses. Fairclough (1995) defined discourse as language in social application, taking on the form of text—whether written, spoken, or visual—when produced within a discursive event. CDA includes examining both linguistic and visual elements, incorporating visual analysis where relevant. Moreover, CDA enables exploring the relationship between social practice and discourse, this approach also enables the examination of social processes and elements of discourse (Fairclough, 1995).

Besides, patriarchy is another significant concern for CDA theorists. Gendered discourse conveys patriarchy where the success of women is shown under the leadership of a supportive husband. The discourses of patriarchy even portray empowered women as powerless. Thus, the Critical Discourse Analysis was helpful for the researcher to observe the construction of gender through visual representation in Bangladeshi textbooks.

Methods

This study employed a mixed-methods approach, combining both quantitative and qualitative research methods, to provide a comprehensive understanding of gender representation in textbooks and teachers’ perceptions. This approach allowed for both in-depth analysis of the visual aspects of gender representation in textbooks and exploration of teachers’ perceptions through interviews. The mixed-methods approach is recognized as a valuable way of combining different types of data to enrich the findings (Creswell, 2005; Dörnyei, 2007).

The study focused on the English for Today (EfT) textbooks used in Bangladesh’s primary education system for Classes I to V. These textbooks are core materials in the Bangladeshi primary school curriculum and are central to classroom instruction. The analysis centered on the visual representation of gender in these textbooks, including the depictions of male and female characters in illustrations, as well as the linguistic representation of gender through text.

Content Analysis of Visuals

A content analysis (CA) approach was used to analyze both the quantitative and qualitative aspects of gender representation in the textbooks. CA allows for the systematic examination of media content to draw inferences (Dörnyei, 2007). The following steps were undertaken:

Visuals (such as illustrations, images, and photographs) included in the analysis were selected based on their direct relevance to gender representation. Only those visuals that depicted human characters or were associated with gendered themes were included. Visuals were excluded if they did not clearly represent a gender or were abstract in nature.

The frequency of male and female images across the textbooks was counted to assess the relative representation of each gender. This included counting the number of illustrations, photographs, and depictions associated with male and female characters.

The visual depictions were then analyzed using a gender lens, guided by Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA). This framework, as outlined by Fairclough (1995), was used to examine how visual texts (images) contribute to the construction of gendered power relations and societal norms.

The content analysis helped the researchers to get the answer to the research question 1.

Interviews with Teachers

To explore teachers’ perceptions of gender representation in the textbooks, semi-structured interviews were conducted. Interviews were chosen as they are well-suited to exploring individual perceptions and insights (Nunan, 1992). A total of 20 teachers from primary schools were interviewed, with ten teachers from urban areas and ten from rural areas. Semi-structured interviews allowed for flexibility in probing teachers’ views while ensuring that key topics were covered.

The interview questions focused on several key areas, including the role of textbooks in promoting gender equality, the influence of textbook writers, and the impact of gender-biased textbooks on classroom teaching. Specific questions also addressed the linguistic and visual representation of gender in the textbooks. The main categories of interview questions included the visual representation of gender in the textbooks, impact of biased representation of images, etc. The recommendations of the teachers for promoting gender equality in the textbooks were also inquired about. The detailed interview questions are attached in the Appendix section.

All ten teachers of the primary schools of the urban area and four teachers in rural areas preferred face-to-face interview sessions. Thus, by making a prior appointment, interviews were conducted by the researcher. Nevertheless, the teachers did not like to be recorded. Thus, notes were taken by the researcher. The other six teachers in rural areas agreed to take part in the Zoom video conferencing platform for the interview. However, four of them were not comfortable recording. Thus, notes were taken from their sessions. The interviews with other two teachers were recorded with their permission. The current study also conducted pilot studies on two teachers of the primary schools before the main study, as Majid et al. (2017) suggested piloting as a crucial and integral aspect of interview to test the interview questions and gain some practice in the interview.

The interviews were transcribed and analyzed using thematic analysis, with a focus on identifying recurring themes related to gender perceptions, and the impact of gender representation on students. The analysis was guided by CDA, with attention to how power dynamics and gender roles were communicated through both language and visual representations. Thematic analysis helped identify patterns and variations in the responses from urban and rural teachers, shedding light on how different contexts might influence perceptions of gender representation. The analysis of interviews helped the researchers to get the answer to the research questions 2 and 3.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was obtained for the study, and participants were informed about the confidentiality of their responses. Teachers were assured anonymity and the option to withdraw at any stage of the interview. The use of pseudonyms (TPSUA for urban teachers and TPSRA for rural teachers) ensured the anonymity of the participants.

Results

Equal visibility of male and female characters is one of the significant criteria to achieve gender equitable textbooks. In order to measure the visibility firstly, the numbers of images referring to men and women in the textbooks were counted in this study by the researcher. Then, the images and captions were analyzed through gender lens. Findings have been presented below through tables and figures.

Class V

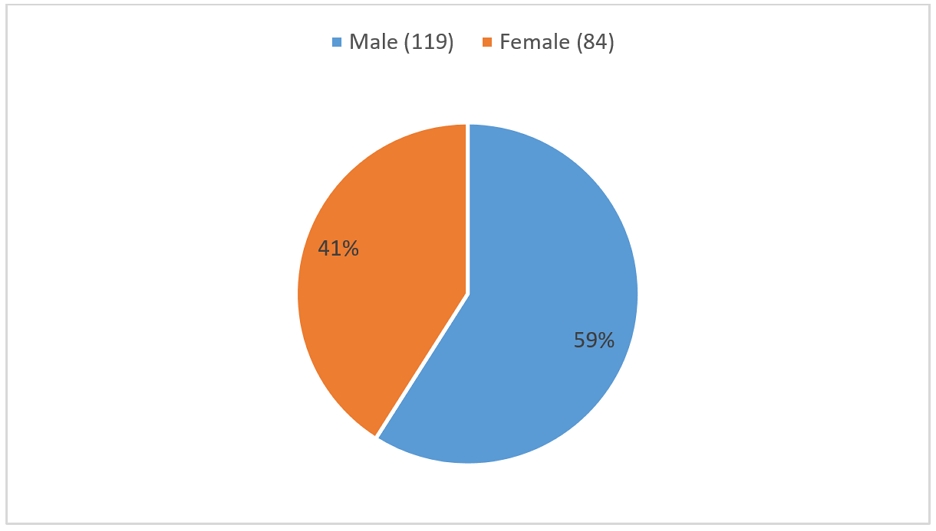

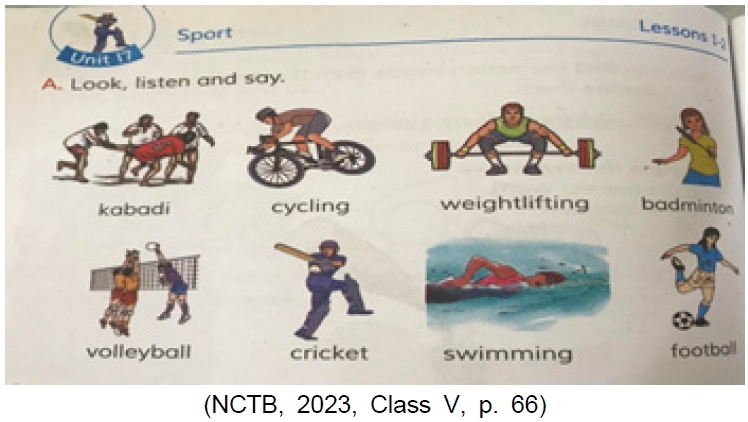

Figure 1 exposed that only 41% female characters were portrayed through images, whereas it was 59% for male characters. Findings indicated unequal representation of female and male characters in the English for Today textbook for Class V. In some images, it was not possible to analyze the content. For example, it was not possible to identify female and male characters clearly in the images of the workers, repairing the bridge and the river flooded the field (NCTB, 2023, Class V, p. 94). Discrimination was found not only in the number of images but also in visualization. For instance, while women were visualized in fashion and health magazine, men were pictured in sports magazine in Unit 4, Lesson 5. Visualizing women in fashion or health and men in sports represented the patriarchal manifestation. Men were also highlighted in sports in unit 17, lessons 1 and 2. These lessons displayed eight types of sports activities through images, including cycling, kabadi, weightlifting, volleyball, badminton, swimming, cricket, and football where men outnumbered. The following figure displayed those images of sports activities.

In Figure 2 women appeared in only two images, shown playing football and badminton. In contrast, men were portrayed participating in kabadi, cycling, weightlifting, and cricket. The images did not clearly indicate whether men and women were involved in volleyball and swimming. However, the textbook (p.66) mentioned Anousha, stating that she went swimming and cycling; therefore, the image of the person in the swimming suit could be Anousha.

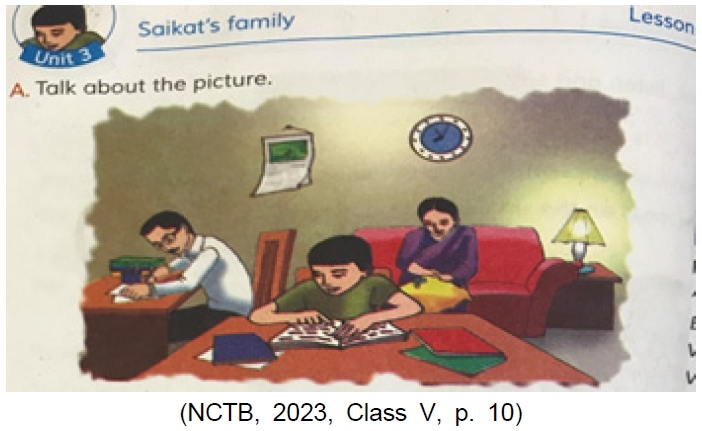

Besides, discrimination was also noticed in characterization through visuals in the following image:

Figure 3 vividly illustrated gender disparity through its portrayal of traditional gender roles. The image depicted a woman engaged in a domestic task—sewing—while the father was shown writing and the boy is reading. This visual reinforces stereotypical gender roles, positioning the woman within a passive, household- oriented role, while the male figures are associated with intellectual and productive activities.

Class IV

Along with the English for Today textbook for Class V, the textbook for Class IV also exposed discrimination in visualization. The following table presented the frequency of male and female images:

Table 1 showed that 55% of the images in the Class IV English textbook depicted male characters, while 45% depicted female characters. The images were manually counted based on distinct visual representations. The numerical difference indicated a higher visibility of male characters, suggesting a gender imbalance. Additionally, female characters were often portrayed in stereotypical roles, reinforcing traditional gender norms.

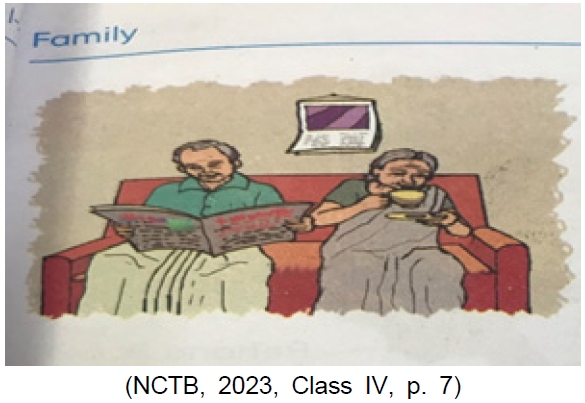

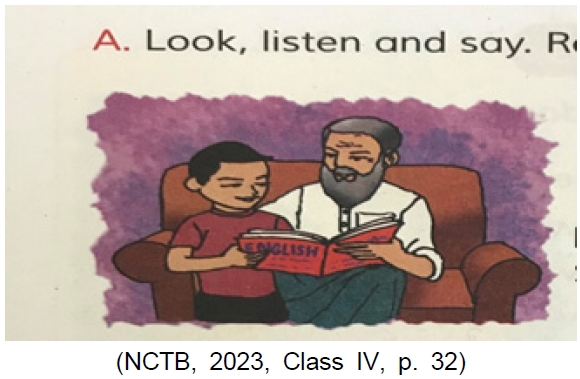

Figure 4 depicted a male character who was reading newspaper, whereas a female character was taking tea. Figure 5 showed that Sagar’s grandfather was reading stories to him; no female character was visualized in the textbook with reading or writing activities.

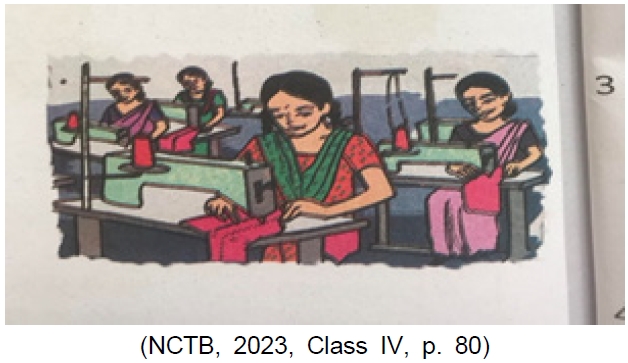

Besides, discriminatory gender role was explored in unit 40, lessons 1-2. The lessons showed an image of a garment factory where all the workers are female.

Women were visualized as garment workers in figure 6. In reality, men also work in the garment factories which was ignored in this textbook.

Class III

Discrimination was also noticed regarding visualization of men and women in the textbook for Class III. The following table presented discrimination in the number of male and female images:

Table 2 showed that 48% female characters and 52% male characters were portrayed through images in the EfT textbook for Class III. Thus, women suffered from low visibility in the textbook for Class III.

Besides, only boys were portrayed in sports activities in the English language textbook for Class III like the textbook for Class V. Unit 33, lessons 1-2, and unit 35, lessons 1-3, of the EfT textbook for Class III showed two images where boys were playing football, but no girls were portrayed in sports throughout the textbook. In contrast, a woman was shown sewing in Unit 35, lessons 4-6. Thus, female characters were visualized in stereotypical roles. Such representation manifested that the indoor work was meant for women whereas sports or outside activities were for men.

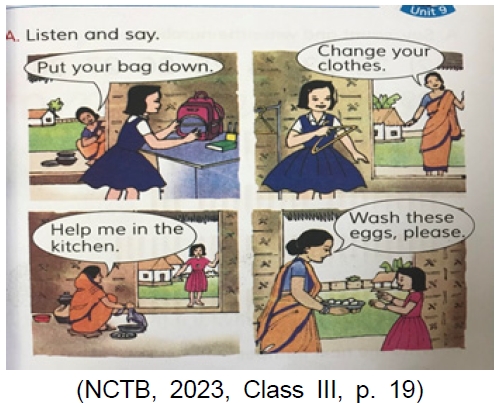

Besides, discrimination in the domestic role was presented through the images and instructions in unit 9, lessons 4-6 of the EfT textbook for Class III. There were four images in these lessons. The first two images contained the instructions of a mother to her daughter when the daughter came home from school. The mother asked her daughter to put her bag down and then change her clothes.

The captions in figure 7 showed that the mother asked the daughter to help her when she came back from school. However, no male character was shown helping in the household menial activities. Such representation manifested biased domestic roles for boys and girls.

Class II

The EfT textbook for Class II was found as an exception regarding the number of male-female images. A high frequency of female images was noticed in the textbook of Class II. Nevertheless, discrimination was revealed in the images. The following table represented the number of images for male and female characters:

Table 3 showed that 60% of female characters and 40% of male characters have been portrayed through images. Though the EfT textbook of Class II showed more images of female characters than male ones, some images demonstrated discriminatory gender roles for boys and girls. Such as, unit 15, lessons 1-4 of Class II showed a girl named Rima who was busy gardening. Rima’s weekly activities were shown through images. Rima was shown putting and nurturing a seed in a tub. However, no boy was shown in such activities and thus, gardening was presented as girls’ work.

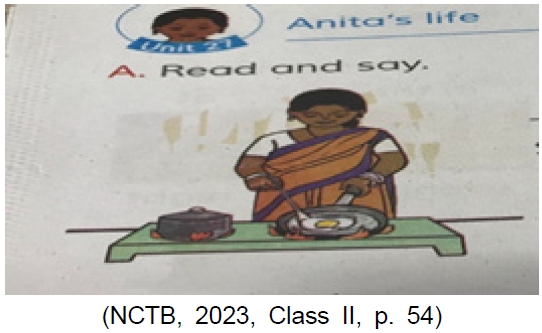

Moreover, The EfT textbook for Class II also reinforced gender-biased domestic roles. In Unit 27, Lessons 1-3, Anita Sarkar was depicted as a school teacher. The story Anita’s Life portrayed her morning routine, stating, “She gets up early in the morning. She cooks breakfast for her family” (NCTB, 2023, Class III, p. 54). Only after completing these household responsibilities does she proceed to her professional duties at school.

Figures 8 and 9 illustrated that Anita Sarker was required to cook before leaving for school. The story suggested that women had to fulfill their household duties first before attending to their professional responsibilities. However, no male figure was depicted as having to manage both domestic and professional tasks.

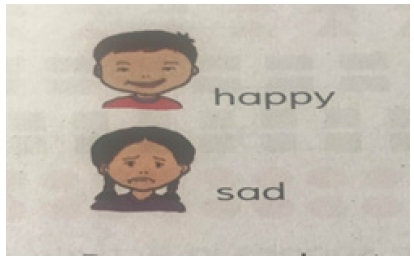

Besides, discrimination was noticed in the facial expressions of a boy and a girl in the following figure:

Figure 10 illustrated a boy depicted with a happy expression, while a girl appeared sad. This contrast in facial expressions is significant because visual representations in textbooks contribute to shaping learners’ perceptions of gender roles and emotions. The consistent portrayal of boys as cheerful and girls as unhappy may reinforce gendered stereotypes, suggesting that positive emotions and confidence are more commonly associated with males, while females are linked to vulnerability or distress. Such representations, when recurring, can contribute to implicit biases about gendered emotional expressions, leading to an imbalance in how boys and girls perceive their roles in society.

Class I

The EfT textbook for Class I also revealed the high frequency of female images like the textbook for Class II. Nevertheless, the textbooks for Class I also conveyed unfair messages through images. The following table has presented the number of male-female images:

Table 4 showed 52.5% female characters and 47.5% male characters through images. Like Class II, the EfT textbook for Class I also showed more female images. Though female characters outnumbered through images, discrimination was noticed in visualization and explanation. For instance, a girl was visualized looking after the domestic animals in unit 2, lesson 15, and a woman was visualized cooking in unit 4, lesson 4, whereas a boy was visualized catching fish in unit 2, lesson 15, and a man was also shown catching fish along with a boy in unit 2, lesson 6. Hence, gender-discriminated roles were depicted through these visuals.

Thus, discrimination was noticed in depicting men and women in the textbooks at the primary level of education in Bangladesh. Men and women were depicted in conventional gender roles through images. Hence, the reinforcement of patriarchal family structure was explored in the EfT textbooks.

Teachers’ Perceptions

Findings from interview sessions of 20 teachers of primary schools (10 from urban area and 10 from rural areas) are presented below:

Ten teachers (five male and five female) of Dhaka city were interviewed with semi-structured questions. The interviews of the respondents were transcribed to obtain the materials for analysis. For confidentiality reasons, all the respondents (ten teachers) were referred to in the findings and discussion sections using pseudonyms. Teachers of the primary schools located in the urban area were referred to as - TPSUA A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I and J.

All the teachers of the urban area agreed that men and women should be equally presented through the images along with the stories and exercises. They argued that learners can easily recall the images. Respondent I added that-

Images have a long-term impact on learners’ minds, as their brains might possess visuals faster than text. Besides, images can simplify complex concepts hastily. Therefore, the images and illustrations in the textbooks should be gender-neutral. (TPSUA I)

Furthermore, they were asked about their perceptions regarding the discrimination of gender in domestic roles through visuals. All the respondents agreed that biased representation exists in textbooks. Moreover, they think that social practice is responsible for discrimination in domestic roles. Respondent TPSUA A mentioned that it is not possible to deny social reality. He added that people in Bangladesh are habituated to seeing women in the household chores and this reality is presented in the textbooks. Respondents TPSUA E and H mentioned that textbook writers’ stereotypical views are reflected in the textbooks. Respondent TPSUA G talked about teachers’ stereotypical views too. She (respondent TPSUA G) mentioned that writers presented the conventional domestic roles and teachers are also familiar with such scenarios therefore, they convey the conventional messages about the domestic roles of women to the learners. However, respondents TPSUA A and C suggested that boys can also be shown doing household chores in the textbooks. As an example, respondent A referred to the images (Figure 7) of unit 9, lessons 4-6 of the EfT textbook for Class III, where a mother asked her daughter to do some household chores when the girl came from school. Respondent TPSUA A mentioned that stories and images in textbooks can show the participation of boys in such activities. Besides, respondent TPSUA C added that nowadays men also participate in domestic work. He added that though men’s participation is not very common, but one or two stories and images could present their (men’s) involvement in mundane works to enhance equality.

Along with the biased representation of domestic roles, the teachers also acknowledged that women are not properly manifested in sports in the textbooks. TPSUA A, E and H mentioned that girls are participating and winning in sports nationally and internationally, but the primary textbooks did not represent the success of women in sports. Respondents TPSUA E and F mentioned girls’ outstanding performances in school sports competitions whereas no story or image shows the achievement of girls in sports. Thus, all the interviewed teachers opined that equality women’s participation and success are underrepresented in the textbooks. Eight respondents out of ten (all female respondents and two male respondents) perceived that underrepresenting female characters in textbooks may enforce alienation among young girls. However, two of the male teachers (TPSUA B and E) did not think that girls will be alienated due to underrepresentation. According to these respondents, female learners are familiar with the underrepresentation of women as they observe discrimination in their families and societies. However, these respondents (TPSUA B and E) felt that both boys and girls should be equally presented in the textbooks for betterment.

All the teachers had a common perception that the biased portrayal of gender in textbooks can have adverse effects on the minds of the primary school learners. All of them agreed that in this age level (6 to 10 years) learners develop their sense of gender equality and thus, equal representation of gender is required for their progress. The interviewed teachers were asked to what extent unequal gender roles and power relationships in the textbooks may lower female learners’ expectations and limit their potential. In response to this question, teacher A argued that such representation will make the girls inferior. Thus, they may not dream to accept any challenges and work for society. Respondents TPSUA B and C and E also had the perception that unequal representation may work as an obstacle in the way of female development. Respondent D added that due to biased representation girls will be degraded day by day. Besides, respondents I and G argued that if textbooks show the active roles and successes of men, then female learners might be disappointed and alienated too. Consequently, such biased representation will discourage girls to work hard. The other three respondents (F, I and J) also had similar perceptions. According to the respondents TPSUA F, I and J, gender biased textbooks will teach the learners (both male and female) about discriminatory gender roles. TPSUA I argued that –

If textbooks portray solely women in indoor roles and men in outdoor roles, no change will take place in society. Both male and female learners will learn the gender differentiated role from their childhood. Though children learn different gender roles from their families, textbooks can show them equal gender roles. (TPSUA I)

Thus, the teachers acknowledged the negative impact of gender disparity in textbooks on young learners. In contrast, all the interviewed teachers agreed that gender equitable examples in the language may inspire girls to determine their professional and societal roles. Hence, they recommended eliminating all sorts of discrimination from the textbooks. They added that material developers should concentrate on portraying images and illustrations to ensure equality.

Among ten teachers in rural areas, six were female and four were male. The number of male-female respondents was selected upon the availability and willingness of the teachers to take part in the research. The interview data were transcribed to obtain the materials for analysis. To maintain confidentiality, all the respondents were referred to in the findings and discussion sections using pseudonyms. Teachers of the primary schools located in the rural areas were referred to as - TPSRA A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I and J.

Like the teachers of the urban area, teachers in rural areas also raised their voices for the necessity of presenting men and women equally through images. One of the respondents (TPSRA C) perceived that young learners go through the images even before stories. Then, all the respondents were asked about their perceptions regarding the portrayal of males and females in the textbooks in sports, leadership roles, and domestic and occupational roles through stories and images.

Respondents TPSRA D and G shared another social reality of the rural areas of Bangladesh that the female learners are highly involved with household chores. Many of the female learners have to do domestic work along with their studies; whereas the boys do not participate in such household chores. Thus, boys can give much time to their studies. All the teachers in the rural areas acknowledged this social reality and they opined that textbooks can be the change makers. TPSRA G mentioned that –

Unlike in urban areas, most of the female learners are bound to do the household chores before and after school. Mothers ask the girls to help them, but they do not ask for any help from boys. Thus, boys remain privileged and study well. (TPSRA G)

However, TPSRA D perceived that –

Textbooks can change such biased mindsets of both boys and girls. If textbooks portray equal domestic roles for both gender girls will no longer think that only they have to do the domestic works. Similarly, boys will be motivated to do the household chore. (TPSRA D)

Thus, the respondents TPSRA D and G perceived that if textbooks display both boys and girls in domestic activities through stories and illustrations, both (boys and girls) will be aware of their equal responsibilities. Consequently, they will be able to spread this idea (about gender equality) in society.

In addition, the respondents were asked about the representation of males and females in sports in Bangladesh in textbooks. In response, all the teachers acknowledged that men were well-represented, but women were underrepresented in the primary textbooks. Respondents TPSRA A, B, I, E and J mentioned that many of the female learners of their schools participate in various sports competitions and achieve success. However, such participation and success of girls were not properly presented in the textbooks.

The findings indicated that both urban and rural teachers recognized gender bias in English language textbooks, particularly in the portrayal of domestic roles, sports, and leadership. However, their perceptions differed in certain aspects. Urban teachers emphasized that textbook representations reflect societal norms but should challenge stereotypes by portraying boys in household chores and highlighting women’s achievements in sports. In contrast, rural teachers, while also advocating for gender equality, stressed that their female students are more actively engaged in domestic work due to social expectations. They viewed textbooks as potential agents of change that could reshape students’ perceptions of gender roles by promoting shared responsibilities. Additionally, while urban teachers were more concerned about the long-term impact of underrepresentation on students’ aspirations, rural teachers focused on the immediate influence of textbooks in shifting entrenched societal mindsets. These differences highlight the contextual variations in teachers’ perspectives, shaped by their students’ experiences.

Finally, the respondents suggested that textbooks ought to accurately depict the balanced involvement of both girls and boys in all sorts of images and activities. Therefore, they recommended updating the existing textbooks and using gender-neutral visuals for improvement.

Discussion

Findings of the study revealed that the majority of images in the primary textbooks exhibited clear signs of gender-based disparity, with female characters being underrepresented. This imbalance was particularly evident in the English for Today (EfT) textbooks for Classes V, IV, and III, where male characters appeared more frequently than their female counterparts. The lack of equal visibility suggests that gender representation in these educational materials does not align with principles of inclusivity and equity.

Along with the number of images, women were discriminated against by men in visualization in the textbooks. Whereas men were more visualized in the sports and outdoor activities and women were visualized in the household routine activities in the EfT textbooks for Classes V, Class IV and Class III. Such representation can transmit the perception to the learners that outdoor activities should be dominated or monopolized by boys whereas; girls are restricted to household chores.

While a woman was visualized in a fashion magazine, men were visualized in a sports magazine in unit 4, lesson 5 in the book of Class V. Visualization of women in fashion and health magazines reflected stereotypical forms of feminine identity as disciplinary practices such as dieting, beauty techniques, fashion tend to transform the female “body” as an object (Foucault, 1977). Discriminatory visualization was also noticed in the textbook for Class III and Class II where men were visualized in sports and women in sewing and household chores (Figures 7, 8, and 9). Men in sports and women with handicrafts, magazines or household chores display traditional stereotypical roles of men and women (Musty, 2015). In his study, Musty also mentioned that such traditional roles of men and women make textbooks gendered. However, women in Bangladesh are actively participating in sports, and economic and political activities, but textbooks did not include this reality. Thus, women’s participation in sports and outdoor activities was not appropriately projected in the textbooks. However, real and appropriate culture needs to be represented in the classroom (Hartman & Judd, 1978). Therefore, textbooks should highlight women’s participation and achievement instead of simply visualizing them in fashion and health magazines or portraying them in handicrafts.

Besides, depicting male characters in reading, and writing and female characters in cooking, and looking after the children also manifest inequality. Figures 3, 4, and 5 depicted a biased representation of gender roles. These figures illustrated the involvement of men in reading and educational activities. In Figure 3, a boy was shown reading, and a man was writing, while a woman was depicted sewing. Figure 4 presented a man reading a newspaper, whereas a woman was simply having tea. Similarly, Figure 5 showed a man assisting his grandson with his studies.

Gender stereotype was embedded as no woman was shown reading the newspaper or writing anything throughout the textbooks (from Class I to Class V). Such underrepresentation can be viewed as an implicit indication of the unworthiness of women (Porreca, 1984). Nevertheless, such negligence of women in the textbooks may limit the expectations of the girls (Suchana, 2021). In contrast, if women were visualized in reading and writing activities or as important people in society, that could motivate girls. Female visibility in the textbooks in important positions in society may inspire girls (Goyal & Rose, 2020).

In addition, visualizing only female characters as garment workers reinforces gender stereotypes. Portraying only the female workers in the garment factory (in Figure 6) revealed discrimination as men also work in the garment factories in Bangladesh. Thus, social reality was not presented there. Besides, women were merely presented as garment workers, but their contribution to the Readymade Garments (RMG) sector was not manifested, whereas this sector (RMG) has emerged as the leading sector of the Bangladeshi economy. Female contribution to the labor market is contributing to the social and economic progress of the country (Chowdhury, 2018). However, such contribution of women in poverty reduction and socioeconomic progress was ignored in the textbooks. Thus, social reality was denied in the textbooks of the primary level of education. Nevertheless, the necessity of representation of the real world in the textbook was indicated by Goyal and Rose (2020). They mentioned that textbooks should keep up with the changes in society and the progress of women in the actual world.

Although gender bias in textbooks remains a significant concern, some encouraging representation was observed in the textbooks for Classes II and I, where female characters appeared more frequently than males. However, despite this numerical advantage, a qualitative analysis of certain images revealed underlying biases in the way female characters were portrayed, indicating that mere visibility does not necessarily translate to equitable representation. For example, unit 15, lessons 1-4 of Class II showed a girl named Rima who was busy gardening, which is an unpaid domestic work and stereotypically associated with girls. Besides, the images of unit 29, lessons 1-3 of Class II visualized a boy with a happy face and a girl with a sad face. Such facial expressions reflected discrimination, as body posture and facial expressions may convey meaning to the learners (Khalid & Ghania, 2019). Besides, images in the textbooks for Class I also displayed discrimination by portraying men in outdoor activities and women in indoor activities.

The above discussion revealed the answer to research question 1 of the study. Instances of embedded inequality have been uncovered through the interpretation of the visual discourses. Such discrimination in visuals carries implicit messages of men’s dominance over women. However, if equal visibility can be displayed in the textbooks, girls may formulate their mindset regarding their participation in all sorts of actions.

Further, in the current study, the interviewed teachers revealed unequal representation of men and women through visuals along with the textual content. Prevailing gender stereotyping in visuals was also noticed by Finnish teachers in the study of Tainio and Karvonen (2015). Like the interviewed teachers in the current study, Finnish teachers mentioned the adverse effects of the discriminatory representation of visuals on young learners. Bangladeshi teachers in the current study argued that discriminatory representation may lower the motivation of female learners. On the other hand, the overrepresentation of men will manifest the power of men. A similar perception was also noticed in the study of Hossain (2018). The interviewed teachers in Hossain’s (2018) study revealed that in the ELT textbooks, male characters were often portrayed as scholars whereas women’s successes had not been focused on. Thus, the participants in Hossain’s study recommended gender-neutral textbooks. However, if the textbooks demonstrate the superiority of men and the inferiority of women, teachers can play the role of minimizing the gap (Goyal & Rose, 2020). According to Goyal and Rose, teachers can critically examine the overrepresentation of men in certain characters. Further, “teachers can make girls play the part of boys and vice-versa to foreground the prevalence of stereotypical notions about gender” (Goyal & Rose, 2020, p. 22). Thus, teachers’ explanation and interpretation regarding the depiction of male and female characters in texts and visuals can promote gender equality. However, teachers in the current study felt that they (teachers) discussed the textual contents, explained the images, and thus conveyed the messages of the textbook writers in the classroom. Therefore, it is the responsibility of the writers to produce gender-neutral content. Thus, answers to research questions 2 and 3 of this study have been revealed by exploring the perceptions and recommendations of the teachers.

To sum up, the perceptions of the teachers of the primary schools located in urban and rural areas of Bangladesh revealed the existence of gender bias in the visuals of the textbooks, and they emphasized the necessity of updating the existing textbooks to ensure equal portrayal of men and women. Thus, the voices of the teachers reflected the necessity of promoting equality through primary textbooks. The research studies across the globe echoed the voices of Bangladeshi teachers.

Conclusions

Finally, the study exposed biased representations of gender in textbooks at the primary level of education in Bangladesh. The content analysis revealed that females are underrepresented and less visible in the images and illustrations. Though there are some encouraging examples, female representations are still much less as compared to those of males. Besides, the examination of teachers’ perceptions revealed their acknowledgement of the discriminatory exhibition of men and women in textbooks. Since visual presentation in the textbooks has a significant influence on young learners’ visual perception, unequal representation of females in the textbooks will signal their invisibility and inferiority in society to them (learners). Hence, teachers in the current study felt the necessity of reviewing the existing textbooks and producing gender-equitable contents. Thus, the study suggested deconstructing stereotypical feminine traits in visuals and producing gender-neutral materials for the improvement of the learners as well as society.

References

-

Bahman, M., & Rahimi, A. (2010). Gender representation in EFL materials: An analysis of English textbooks of Iranian high schools. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 9, 273–277.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.12.149]

- Brown, H. D. (2000). Principles of language learning and teaching. Pearson.

-

Chowdhury, E. H. (2018). Made in Bangladesh: The romance of the new woman. In N.Hussein (Ed.) Rethinking New Womanhood (pp. 47–70). Palgrave Macmillan.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-67900-6_3]

-

Chun, J., & Kim, M. H. (2024). Gender Representation in the Korean Basic Dictionary for Language Learners through Gendered Personal Nouns. Asian Women, 40(4), 55–77.

[https://doi.org/10.14431/aw.2024.12.40.4.55]

- Creswell, J. W. (2005). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. Pearson.

-

Curaming, E. M., & Curaming, R. A. (2020). Gender (in) equality in English textbooks in the Philippines: A critical discourse analysis. Sexuality & Culture, 24(4), 1167–1188.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-020-09750-4]

- Dornyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics. Oxford University Press.

- Fairclough, N. (1995). Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language. Longman.

- Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and punish (A. Sheridan, Trans.). Pantheon. (Original work published 1975).

-

Ghoushchi, S., Yazdani, H., Dowlatabadi, H., & Ahmadian, M. (2021). A multimodal discourse analysis of pictures in ELT textbooks: Modes of communication in focus. Jordan Journal of Modern Languages and Literatures, 13(4), 623–644.

[https://doi.org/10.47012/jjmll.13.4.2]

-

Giaschi, P. (2000). Gender positioning in education: A critical image analysis of ESL texts. TESL Canada Journal, 32-46.

[https://doi.org/10.18806/tesl.v18i1.898]

-

Goyal, R., & Rose, H. (2020). Stilettoed Damsels in Distress: the (un) changing depictions of gender in a business English textbook. Linguistics and Education, 58, 1–29.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2020.100820]

-

Hartman, P. L., & Judd, E. L. (1978). Sexism and TESOL materials. TESOL quarterly, 12(4) 383–393.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/3586137]

- Hossain, A. T. (2018). Depiction of gender in ELT textbooks: gender stereotyping in language and its effect on secondary level students. [Bachelor’s thesis, BRAC University]. BracU Institutional Repository. http://hdl.handle.net/10361/10756

-

Isnaini, F., Setyono, B., & Ariyanto, S. (2019). A visual semiotic analysis of multicultural values in an Indonesian English textbook. Indonesian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 8(3), 536–544. http://repository.unej.ac.id/

[https://doi.org/10.17509/ijal.v8i3.15253]

-

Khalid, Z., & Ghania, O. (2019). Gender positioning in the visual discourse of Algerian secondary education EFL textbooks: Critical image analysis vs teachers’ perceptions. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 15(3), 773–793.

[https://doi.org/10.17263/jlls.631510]

-

Li, X. (2016). Holding up half the sky? The continuity and change of visual gender representation in elementary language textbooks in post-Mao China. Asian Journal of Women's Studies, 22(4), 477–496.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/12259276.2016.1242945s]

-

Majid, M. A. A., Othman, M., Mohamad, S. F., Lim, S. A. H., & Yusof, A. (2017). Piloting for interviews in qualitative research: Operationalization and lessons learnt. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 7(4), 1073–1080.

[https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v7-i4/2916]

- Ministry of Planning. (2022). Bangladesh Sample Vital Statistics 2022. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. https://file-khulna.portal.gov.bd/uploads/77aaa0cf-d5fb-48a6-a478-bac4c228eab2//65c/865/035/65c8650359310096994689.pdf

-

Musty, N. (2015). Teaching Inequality: A study of gender identity in EFL Textbooks. Identity Papers: A journal of British and Irish studies, 1(2), 37–56.

[https://doi.org/10.5920/idp.2015.1237]

- National Curriculum and Textbook Board. (2023). English for Today Class 5. NCTB.

- National Curriculum and Textbook Board. (2023). English for Today Class 4. NCTB.

- National Curriculum and Textbook Board. (2023). English for Today Class 3. NCTB.

- National Curriculum and Textbook Board. (2023). English for Today Class 2. NCTB.

- National Curriculum and Textbook Board. (2023). English for Today Class 1. NCTB.

- Narayan, U. (2004). The project of feminist epistemology: Perspectives from a non-western feminist. In S. G. Harding (Eds.), The feminist standpoint theory reader: Intellectual and political controversies (pp. 213–224). Psychology Press.

- Nunan, D., David, N., & Swan, M. (1992). Research methods in language learning. Cambridge university press.

-

Nur, S., Short, M., & Ashman, G. (2021). From the infrastructure to the big picture: A critical reading of English language education policy and planning in Bangladesh. In S. Sultana, M. M. Roshid, M. Z. Haider, M. M. N. Kabir & M. H. Khan (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of English language education in Bangladesh (pp. 17–32). Routledge.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429356803-2]

-

Porreca, K. L. (1984). Sexism in current ESL textbooks. TESOL quarterly, 18(4), 705–724.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/3586584]

-

Sovič, A., & Hus, V. (2016). Semiotic analysis of the textbooks for young learners. Creative Education, 7(04), 639–645.

[https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2016.74066]

- Shrewsbury, C. M. (1987). What is feminist pedagogy? Women's Studies Quarterly, 15(3/4), 6–14.

-

Suchana, A. A. (2021). Investigating gender equity in a primary level of English language textbook in Bangladesh. In S. Sultana, M. M. Roshid, M. Z. Haider, M. M. N. Kabir & M. H. Khan (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of English language education in Bangladesh (pp. 298–311). Routledge.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429356803-19]

-

Sunderland, J. (2006). Language and gender: An advanced resource book. Routledge.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203456491]

- Tainio, L., & Karvonen, U. (2015). Finnish Teachers Exploring Gender Bias in School Textbooks. In S. Mills & A. S. Mustapha (Eds.), Gender Representations in Learning Materials: International Perspectives (pp. 124–149). Routledge. http://hdl.handle.net/10138/230991

-

Tomlinson, B. (2012). Materials development for language learning and teaching. Language teaching, 45(2), 143-179.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444811000528]

-

Ullah, H., & Skelton, C. (2013). Gender representation in the public sector schools textbooks of Pakistan. Educational Studies, 39(2), 183–194.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2012.702892]

Appendix

Appendix: Interview Questions

Perceptions of the teachers regarding visual representation of gender in English language textbooks:

1. Visual representation of gender in the textbooks

- a) How far do you agree that men and women should be equally presented through the images along with the stories and exercises?

- b) How is the role of leadership presented in the textbook?

- c) How far men and women have been presented in active roles?

- d) Representation of males and females is very typical in domestic role. Do you agree? If yes/no, why and how?

- e) What is your opinion about women representation in sports in Bangladesh? To what extent women in sports are represented in textbooks?

- f) Do you perceive that women’s participation and success are underrepresented in the textbooks? If yes/no, why and how?

2. Impact of biased representation of images in the textbooks

- a) To what extent do you think that unequal gender roles and power relationship through images in the textbooks may lower female learners’ expectations and limit their potentials?

- b) How far do you agree that gender equitable images may inspire girls to determine their professional and societal role?

3. Recommendation

- In what ways do you think that gender equity can be enhanced in the primary textbooks?

Biographical Note: Afroza Aziz Suchana is an Associate Professor in the Department of English at the University of Asia Pacific, Bangladesh. She obtained her Ph.D. from the Institute of Modern Languages, University of Dhaka. Earlier, she completed her B.A. (Hons) and M.A. in Applied Linguistics and ELT from the Department of English, University of Dhaka. With a robust focus on gender equality in textbooks, materials evaluation, and the integration of technology in education, alongside an exploration into code-switching, she has both published and presented her findings in these significant domains at home and abroad. Email: suchanadu@gmail.com