Fragmented Anatomical Parts and Gender Representation: A Comparative Feminist Stylistic Analysis of Male and Female Bodies in Faruqi’s The Mirror of Beauty

Abstract

Keeping in view the general belief of the feminists that women are often discriminated through biased use of linguistic choices, the present study examines the fragmentation of women and men body parts in an Indian novel titled The Mirror of Beauty (TMOB) by Shamsur Rahman Faruqi (2013). Following a qualitative content analysis and taking the insights drawn from fragmentation framework as suggested by Mills (1995), the researchers delved deeply into the text to unfold how body parts of characters are described in relation to gender representation. The study, though, started with Mills’s (1995) assertions, yet it ended with challenging and extending her ideas of fragmentation. Firstly, the study found that the bodies of both the women and men are fragmented. Secondly, the men, too, are described negatively through their body parts though in lesser examples. And thirdly, it has been found that other than their body parts, the women are projected in a sexualized way through their whole bodies as well. Based on these findings, the researchers maintain that Faruqi (2013) exhibits a biased linguistic attitude towards gender in his TMOB where women’s bodies are fragmented to present them negatively while the descriptions of men’s body parts project them positively.

Keywords:

Fragmentation, feminist stylistics, body parts, gendered ideologies, The Mirror of BeautyIntroduction

The representation of women and men in literature has been an interesting area of inquiry in the field of language and gender. The focus of the present study is to carry out a literary analysis of Shamsur Rahman Faruqi’s novel The Mirror of Beauty (2013) to analyze gender representation constructed through a description of women and men’s body parts. For this purpose, the fragmentation framework as suggested by Mills (1995) in her feminist stylistic analysis model is utilized. The term fragmentation is associated with several fields of study like media, biology, film and drama criticism, linguistics, stylistics, gender studies and literature. However, in language and gender studies, the feminists use fragmentation in relation to representation of the female body in any text i.e., literary, and non-literary texts, carrying and conveying gender related themes. Fragmentation is “the process whereby characters in texts are described in terms of their body-parts instead of as people” (Mills, 1995, p. 207). The feminists claim that this technique can be used to represent women’s bodies through different modes like pictures, commercials, statues, sculptures, paintings, movies, and literary texts. Mills (1995), too, asserts that the description of fragmented bodies is mostly done for the representation of women than that of the men. She further claims that such a presentation of the female through her body parts draws a negative image of the women where they are described as passive, natural and consumable objects. This fragmentation of the female characters co-occurs with male focalization. The researchers claim that this anatomical description of female body parts can represent them either positively (Green, 2016; Katrak, 2006; Morguson, 2013) or negatively (Kappeler,1986). From Mills’s (1995) perspective, fragmentation is a process whereby “characters in texts are described in terms of their body parts instead of as people” (p. 207). Hence, when described in relation to its body parts, a body is called a fragmented body. In literature this fragmentation, particularly that of female bodies in texts is a way to construct the culture and social portrayals as claimed by Jeffries (2007) and Mills (1995). Though this technique of fragmentation is mostly observed in pornographic literature, but genres of literature like romantic novels, short stories, dramas, and love poetry also present women as sexual objects by highlighting body parts. The utility of the investigation of fragmentation techniques for a better understanding of ideological messages and positive or negative attitudes towards gender depiction is maintained by Al-Nakeeb (2018) as well. The present study with a focus on a male writer’s linguistic choices for a description of his characters’ anatomical parts is significant as it will prove helpful to enhance the understanding of both the readers and the writers that how language can be used to affirm, propagate, or resist gender ideologies. This study is also of significance as no comparative study has been conducted yet to analyze the selected novel by Faruqi (2013) through feminist stylistics framework. The importance of such studies carried out to analyze literary work is also suggested as below:

Every study which contributes to the comprehension and interpretation of a literary work is legitimate. Every kind of study is welcomed if it adds to our knowledge of literary work or if it permits us to feel and enjoy it better (Alonso, 1942).

As for as theoretical significance of this study is concerned, it is expected to help in elaborating the practical implication of the existing theory and framework of Mills’ (1995) feminist stylistics. Hence, it will add new insights in the growing body of the knowledge in different fields like language and literature, sociolinguistics, sexism, feminism, and feminist stylistics. The findings of the study can be significant at a practical and pedagogical level as well where it will set the stage for the language teachers, students, researchers, scholars, writers and readers by suggesting the ways to read and analyze any text from gender perspective. This will prove helpful for them to carry out their relevant activities of the teaching and learning of language and literature, reading and analyzing language of different texts, and composing written texts that are free of gender bias. Hence, paving the way to avoid the sexist use of language and promoting the use of a biased free language to end discrimination against any gender.

With the aim to unravel the textual representation of women and men characters through their body parts, the researchers have set the following research question:

1. How are the characters’ anatomical parts exploited to represent women characters in comparison to men characters with reference to gendered ideologies in The Mirror of Beauty?

Literature review

Reviewing the studies carried out to see the relationship between language and gender, Meyerhoff (2019) claims that the “field of language and gender is one of the most dynamic in sociolinguistics” (p. 201). The researchers like Jespersen (1922) and Lakoff (1975) maintained that there is a close relationship between gender and language. The development of research on language and gender has undergone different phases. The first phase focused on differences between the speech of women and men. The second phase was concerned with finding the differences in the writings of female and male writers. The later research in the third phase started bringing into light the sexist use of language in different forms of discourse either written or spoken. In accordance with this third phase, the present research unpacks the relationship between linguistic choices and gender description in a written discourse i.e., a novel utilizing Mills’s (1995) model of feminist stylistics.

Several discourses have been analyzed from different perspectives utilizing this model of analysis to develop an understanding of how female characters are represented in certain texts. These studies conducted by using feminist stylistics framework to analyze representation of women in literary and non-literary texts show the utility of this framework to explore the linguistic bias in order to struggle for the emancipation of womanhood (Ufot, 2012). While analyzing online texts, Page (2010) found that the language used to express sexual experiences shows that “instead of representing a shift towards feminine agency, the verbal constructions either depersonalize the sex acts⋯ or continue to represent the woman as the acted upon participant” (p. 81). Other than online texts, the language of newspapers has also been analyzed utilizing feminist stylistics approach by Laine and Watson (2014). The researchers like Khan and Ateeq (2017) and Sher and Saleem (2023) have utilized feminist stylistics framework to see gender differences in matrimonial ads. Advertisements, too, have been analyzed to see gender representation through the lens of feminist stylistics approach. For example, Coffey (2013) analyzed the grammatical structure to highlight how men’s conduct, and their related ideologies are institutionalized in women’s magazines. Another contribution in this field is by Riaz and Tehseem (2015) who identified how women are presented as sex objects in media advertisements. Other studies conducted to analyze print media advertisements have reached at the conclusion that advertisers are “propagators of gender ideologies” (Radzi & Musa, 2017, p. 35).

Fragmentation, one of the frameworks from feminist stylistics theory, has been analyzed by several feminist critics with reference to viewing the female body via its anatomical parts. Mills (1995) proposed the idea that females are presented as sexual objects where their bodies are fragmented and categorized but the same does not happen in the projection of male characters (Mills, 1995). The studies within feminist literary criticism carried out to see women’s bodies concluded that the biased representation of females through their body parts relegates them to mere objects (Brown, 2012; Innes-Parker, 1995; June, 2010).

In recent studies carried out by Rennick et al. (2023) and SooHoo (2022), it was revealed that female representation is biased where women characters are projected as sexualized objects through their body images in video games. Other than this, the use of fragmentation in literary texts has also been analyzed through feminist stylistics lens. In his study of a Yemeni novel, Al-Nakeeb (2018) found that the bodies of females and males are, though, equally fragmented, yet represent women and men differently where the female characters are projected through their beauty and sexual appeal while the men are fragmented to highlight their physical strengths/deficiencies and their social power. The negative image of the women is also built through collocations as highlighted by Al-Nakeeb and Mufleh (2018) and Alzamil et al., (2023) in their respective studies. They found that male characters are represented as cheerful and lively while female characters are presented as dependent ones. Likewise, in a study conducted by Wulandari (2018), it was found that women are described through their body parts while men are described in relation to their overall appearance. Hence, women are not presented as a whole entity which demeans their roles in the text. This representation of gender through a description of female body parts has been seen as a tool for perpetuating gender stereotypes by some recent studies as well. For example, while analyzing Roy’s The God of Small Things (1997), Ansar and Hussain (2025) maintained that bodily descriptions of the female characters reinforce females’ subjugation within a male-dominated society. Likewise, in their recent study of a novel titled Lucy (1990), Achili and Rahil (2025) also found that objectification of women in literature is reinforced through the description of their body parts like eyes, stomach, feet and skin.

The present study is expected to be a good addition in this ongoing field of feminist studies focusing on the relationship between language and gender as it analyzes the use of fragmentation in an Indian English novel The Mirror of Beauty written by Shamsur Rahman Faruqi and published in 2013. Faruqi’s (2013) adherence to the stylistic conventions of classical Urdu and Persian storytelling with a touch of cultural and historical realism in this novel has invited a number of researchers to examine this novel from different perspectives. The previous studies have analyzed this work from feminist, historical and postcolonial perspectives. For example, Fayyaz and Jabbar (2024) have analyzed this work from a feminist perspective with a focus on the description of female beauty in this novel. Khan and Khatoon (2021), have investigated this text with reference to defiance against patriarchal norms from a postcolonial perspective. Similarly in a study conducted by Kayani and Anwar (2022) with a focus on fragmented use of two body parts i.e., eyes and face to see gender depiction in Faruqi’s (2013) work, it has been found that female characters’ sexuality and physical attractiveness is highlighted through their anatomical parts while men are portrayed as physically strong characters showing positive personality traits.

In contrast to these previous studies, the present study takes a different approach with a special focus on the stylistic and thematic interpretation of body parts, both as a whole and in parts, for women and men characters in The Mirror of Beauty (2013). The researchers have selected this novel because it offers a panoramic view of 19th-century India where a rich description of male and female body parts is given to showcase gender ideologies of that time. These gendered portrayals through body parts description can be observed as a reconstruction of a past India where gender ideologies were deeply rooted in cultural and societal expectations. This study is expected to make a good contribution in the field of language and gender from fragmentation perspective as it is claimed that literary analysis is helpful in uncovering the deeper meanings contained within literary texts (Imran et al., 2023; Manyak & Manyak, 2021; Raza et al., 2022).

Theoretical Framework

The present study is based on Mills’s (1995) feminist stylistics model deeply rooted in feminist literary criticism. By highlighting the issue of linguistic sexism, Mills (1995) suggested different ways to examine texts from a feminist perspective in her feminist stylistics which is both a theory and a method. Feminist stylistics is defined as “a form of politically motivated stylistics whose aim is to develop an awareness of the way gender is handled in texts.” (Mills, 1995, p. 165). This theory emerged as a field of study from stylistics which, as a branch of applied linguistics, implies both literary criticism and linguistics (Saadia et al., 2015). It is defined as an approach “which pays attention to the formal features of the text and its reception within a reading community in relation to ideology” (Mcrae & Clark as cited in Davies & Elder, 2004, p. 332). Keeping in mind the basic aim of this study, Mills’s (1995) model is chosen because it incorporates the feminist theory into stylistics. Moreover, its concern with the manifestation of gender in general in texts is also suitable for this study where the researchers have an interest to analyze both the women and men characters. It goes with the concern of Mills’s (1995) model which claims that how its aim is to see “how women and men are constructed at a representational and at an actual level” (p. 3).

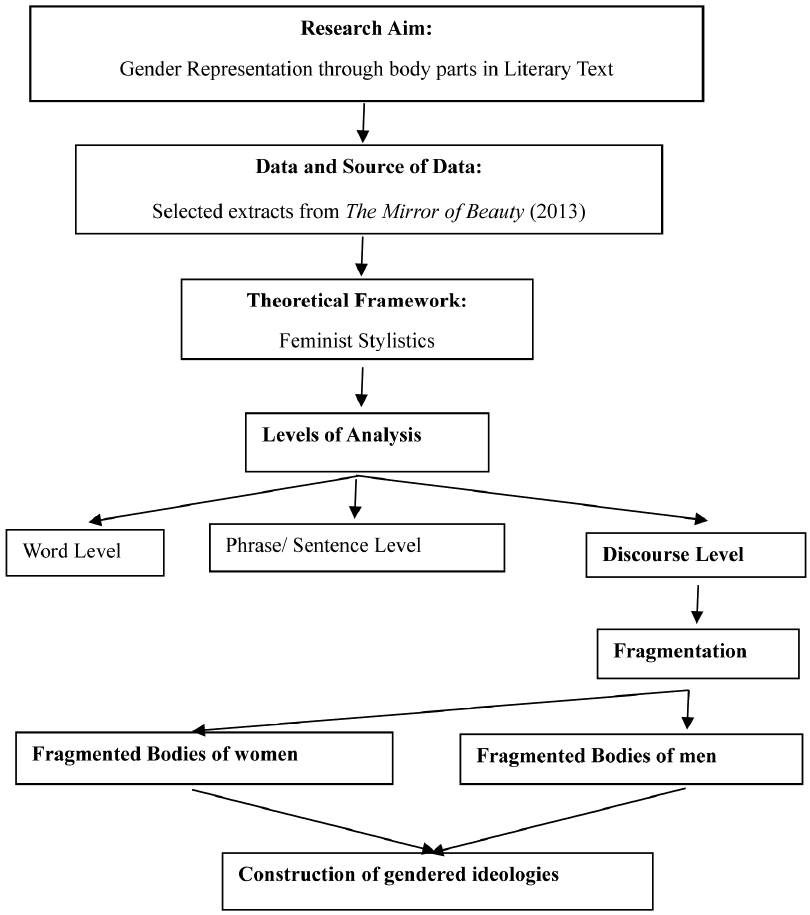

The feminist stylistics model of analysis recommends carrying out a linguistic analysis of any text at three levels: word level, clause/sentence level and discourse level. The word level allows the researchers to investigate the sexist/nonsexist use of generic nouns and pronouns, naming and semantic derogation. At the level of sentence, the attention is paid to the sexist use of phrases and clauses in relation to jokes, transitivity, and metaphors. The third level, the discourse analysis, concerns the ways in which characters are described in relation to their personality, roles, and fragmentation. From within these three levels and discursive frameworks, the present study chooses the framework of fragmentation at discourse level to investigate how the bodies of women and men are described in a text with what ideologies.

In proposing to analyze the text at discourse level, Mills (1995), in fact, tries to connect the word and the phrase with a “larger notion of ideology” (p. 123). She suggests that the analysis of discourse should be made as “discourse is profoundly gendered” (p. 124). The characters appearing in a literary text are not just the result of the play of words, but these carry a whole mindset and ideology about certain phenomena prevalent in society. The writers, intentionally or unintentionally, either cement or challenge existing ideologies related to gender through a representation of their characters. Mills (1995), while talking about the construction of the characters, claims that the writers make linguistic choices in connection with gender stereotypes. She further asserts that characters are not “simulacra of humans” (p. 123). According to her, characters are nothing more than words which are constructed and understood based on different gender stereotypes prevalent in society.

The information provided by the writer about his/her characters can be direct or indirect as suggested by Culpeper and Fernandez-Quintanilla (2017). The information regarding characters’ physical appearance or their personal qualities when described by the writer is called direct characterization. In indirect characterization the narrator highlights the character’s strength and feelings by narrating their actions and feelings or by the comments of other characters about a particular character. The art of characterization is very important for fiction writers to give a realistic touch to their work. Though a realistic description of characters wins both applause and appeal of the readers, the characters that appear to be real are not actually real. These characters vary gender and nature wise. The ideas and stereotypes prevalent in society do affect the writers while describing their characters.

The utility of feminist stylistic framework has been maintained by a number of researchers who have used this model of analysis to explore gendered use of language in fairytales (Arikan, 2016), movies (Bado, 2021), poems (Ashimbuli,2022; Hama, 2017; Woldemariam, 2018), short stories (Denopra, 2012; Kudus, 2008; Savinainen, 2001; Verma & Dahiya, 2016) and novels (Anwar et al., 2023; Anwar et al., 2024; Atoke, 2021; Darweesh & Ghayadh, 2016; David, 2020; Isti'anah, 2019; Kang &Wu, 2015; Kayani & Anwar, 2022; Kayani et al., 2023; Khazai et al., 2016; Supriyadi, 2014; Ufot, 2012). All these studies have explored the language of their relevant texts at different levels of word, clause and discourse and have found feminist stylistic framework useful to carry out their linguistic analysis from gender perspective.

In accordance with this interconnection of feminist stylistic model to analyze the relationship between gender and language, the present study researchers attempt to examine the construction of both the male and female characters in the selected text with a focus on the description of their body parts.

Research Methodology

Keeping in view the basic aim of this study the researchers have opted for the qualitative research method. In qualitative research as claimed by Vanderstoep and Johnston (2008), a researcher produces a narrative or textual description of the phenomenon under study. From within qualitative research, the qualitative content analysis (QCA) method, which was defined as “a research method for the subjective interpretation of the content of text data through the systematic classification process of coding and identifying themes or patterns” (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005, p. 1278), was adopted. Krippendorff (2018) asserts that this method of study examines the existence, meanings, and connections of words and concepts which are embedded in cultural artifacts. Moreover, the processes in QCA, like data collection, data analysis, and interpretation, do not always follow a predetermined structure to discover implicit themes in content (Bryman, 2016; White & Marsh, 2006).

Data, Source of Data and Data Sampling Technique

The data of the present study are collected in the form of written extracts occurring at the discourse level from Faruqi’s (2013) novel The Mirror of Beauty. Only these extracts are considered for analysis which contribute to the description of women or men in relation to their body parts. The sampling technique used to collect data for this study is purposive sampling which is defined by Creswell and Poth (2016) as a sampling method in qualitative research where the researchers select individual sites for the study because they purposefully understand the research problem and central phenomenon in the study. Keeping in mind the research objectives and scope of this study, only those instances from the texts were considered as data which carried the theme of gender through a description of body parts at the discourse level. This preset criterion goes with Alvi’s (2016) claim that “in purposive sampling the sample is approached having a prior purpose in mind. The criteria of the elements who are to be included in the study is predefined” (p. 30).

Procedure

The present study utilizes qualitative content analysis for analyzing the text by following a step-by-step procedure as Mayring (2004) claims this approach to be “an approach of empirical, methodological controlled analysis of texts within their context of communication, following content analytic rules and step by step models, without rash quantification” (p. 2). Three –phase schema of textual analysis as suggested by Kibiswa (2019) for qualitative researchers is adopted. This schema is based on an iterative and non-linear way inspired by the schemas described by Elo and Kyngäs (2008). At the preparation phase, the researchers decided on the material and meaning unit for this study, i.e., a novel and the extracts describing characters through their body parts. This was followed by a close reading of the text to highlight and tag the meaning units to extract relevant texts with a description of male and female body parts. At the data analysis phase, these highlighted textual units were marked on separate sheets for women and men characters to reach at gender ideologies related to the depiction of gender. The researchers then gave description in the form of text form with explanations and references. The body parts within the identified extracts were discussed and highlighted in relation to contextual explanation and the built-up images of women and men were analyzed in relation to positive and negative images of both. Figure 1 gives an overall view of the structure of the study.

Results and Discussion

Mills (1995) asserts that the female characters are described through fragmentation where they are not described as a whole body, but their body parts are described to arouse and enhance their sexual appeal. Keeping in view these claims, the present study researchers have found that both the bodies of women and men are fragmented with a description of their body parts but with different effects and for different purposes in this novel. The following discussion presents an analysis of these body parts to show their semantic functioning for each gender.

Fragmented Bodies and Women’s Representation

The data shows that women are described through their body parts at two levels. Firstly, it arouses the sexual appeal of the female body and secondly it also carries and conveys some other traits of the females like their beauty, delicacy, shyness, and their oppressed and melancholic situation. The analysis of relevant examples from the data is presented in the following discussion carried out according to constructed ideologies.

Women are Sexually Desirable

The analysis showed that in most of the cases women are projected as sexually desirable through a description of their body or body parts. First considering the color words used to describe the women’s body parts like hair, face, and lips etc., it has been observed that such a description carries the connotations of sexual appeal and sexual availability with it. Mills (1995) in this regard claims that these refer to a position of voyeurism—a position of meticulous cataloguing of differences. In TMOB, several body parts are described in relation to their color. For example, Wazir’s face is described as “The light brown skin of her forehead, face and chin” (TMOB, p. 260), the light brown complexion of the face connotes sexual desirability as was claimed by Qayyum et al., (2019) in their relevant study. The women are also presented sexually attractive by giving a description of their eyes in relation to their black or brown color. The text describes these as “her black eyes, long, slanting, like the starfruit” (TMOB, p. 261), “their eyes very dark brown and her eyes black [⋯] were like big almonds” (TMOB, p. 405). In another description where a male character is looking into the eyes of a female character shows the intoxication these ‘dark brown eyes’ of the female provide as given in this excerpt: “He held her chin and raised her head so that he could look into those eyes, dark brown ⋯her large eloquent eyes” (TMOB, p. 229).

Other than the color of their face and eyes, women are also described through the description of their hair and lips as well. Their sexual appeal and availability are highlighted through their hair in the text. The blackness of their hair connotes sexual appeal generally associated with the word Brunette. Jamila and Habiba are described as “their hair was thick and dense, bright black tresses framed their faces” (TMOB, p. 403). Other than this Rahat Afza is also described in relation to her hair as in “her hair was thick and bright and black” (TMOB, p. 405). The desert women are also described as “brown hair shot with grey” (TMOB, p. 226). The sensual appeal of the women is also highlighted through the color of their lips as rosy-pink or pink. Rahat Afza is described as “She had a small mouth with delicate lips, naturally rose pink” (TMOB, p. 405). Jahangira Begum is also described through her “delicate pink lips” (TMOB, p. 639). Such a description of the lips with pink color is meant to present women sexually attractive.

Other than the use of body parts with reference to colors, the women are also described through a direct appeal of their sexual body and sexual organs for several times in the text. First considering their body, the text portrays Wazir’s body that possesses a sexual appeal for men. For example, the sexual appeal of Wazir’s body is highlighted when text presents it in relation to its curves as in “all the contours of Wazir’s body, all the curves and promontories, were prominent [⋯] give intimation of those hidden mysteries (TMOB, p. 451). The hidden mysteries refer to the hidden sexual organs and the pleasures associated with these. Again, Wazir’s body is described in relation to how it attracts men towards itself: “Immense attraction that her body and her inner being as reflected in her external presence wielded over men of all types” (TMOB, p. 485). On another occasion, Faruqi (2013) again gives a description of Wazir’s body that arouses feeling of sexual appeal as in “extremely intriguing sense of womanhood [⋯] seemed to be emanating [⋯] from Wazir Khanam’s body” (TMOB, p. 283). Later in the text, Wazir is shown to be conscious about her body and avoids suckling her babies because she thinks it would “cause her body to lose its youthful tightness and proportionate shapeliness” (TMOB, p. 228). Such a description of the body in relation to its youthful tightness and shape carries sexual appeal with it.

Other than the character of Wazir Khanam, Amir Bahu is another female character whose body alone is enough to describe the female sexual appeal as the text narrates “full youthfulness seemed to flow out of her body” (TMOB, p. 571). Moreover, the bodies of the female body guards though described in relation to their strength also highlight their sexual appeal as in “their jet bodies were glossy with health [⋯] their breasts were high, their waists were narrow, their hips heavy” (TMOB, p. 444) and “bodies extremely well knit, with powerful backs and arms”(TMOB, p. 460).The tightness of Wazir’s body is described as “the spangle of the ups and downs of her body, tight as a bow”(TMOB, p. 260). Likewise, the description such as “the softness of an elegant, well-formed body” (TMOB, p. 273) creates the same effect. Hence, it can be claimed that based on these examples from the text that even the body of a female can be described in such a way that can arouse sexual appeal.

Other than body, the description of the body parts of different female characters is also used to present women as seductive beings. The minute detail of their body parts as given by Faruqi (2014) is noteworthy as it carries deep sexual connotations with it. Wazir Khanam, the heroine of the novel, is described through her body parts for several times. She is described through her “narrow waist, heavy hips and prominent breasts” (TMOB, p. 389), “the well-formed neck” (TMOB, p. 261), “the slopes of her breasts” (TMOB, p. 391), “her breasts and her body below the pelvis” (TMOB, p. 397), “her thighs [⋯] the curves of her upper body [⋯] the rebellious lines of her neck and breast” (TMOB, p. 395), “her breasts fill and tighten” (TMOB, p. 894), “her face, her lips, her eyes, her breasts” (TMOB, p. 503). All these descriptions of her body parts represent her in parts where each part has its own sexual appeal. Her eyes are described in relation to her sexuality as in “The eyes reflected such a powerful consciousness of youth and sexuality” (TMOB, pp. 803-804). Even the text describes Wazir’s sexual appeal by giving a description of the private part of her body as in “the mirror showed everything, even the slight elevation of the Mount of Venus and the suggestion of a little patch of darker sward on it” (TMOB, p. 390). The fragmented description of Wazir Khanam in TMOB again hints at her sexual appeal and availability through the description as below:

Her neck and the hint of her cleavage, the soft-swelling breasts, youthful muscles⋯ her hips and breasts had become a trifle bigger and heavier⋯shrunk her body⋯glimpse of her cleavage and breasts was enough to slay even the most hardened gazer (TMOB, p. 312)

In accordance with Attridge’s (1988) claim that sexuality thrives on the separation of the body into independent parts, the present study finds that the element of fragmentation is obvious in TMOB for the character of Wazir Khanam. She is described through her anatomical body parts such as neck, breasts, hips, waist, eyes, and face. The description of her body parts in relation to certain adjectives as given in the following excerpt enhances the sexual appeal and meaning of her body. She is called a fille de joie i.e., a prostitute whose whole body is offering itself to the gazer to enjoy and relish it.

The body slim, svelte [⋯] the neck proud like a peacock’s, the breasts and the hips heavy but not big, slender waist, large, [⋯] lickable relish raining everywhere on her face⋯the whole of her body speaking the language of a fille de joie (TMOB, p.344)

Likewise, in another excerpt from TMOB, her naked body is described in parts from the perspective of a male gazer which projects her as a beautiful and sexual object.

Well-shaped, graceful tight buttocks, thighs as if moulded from a master potter’s mould; waist narrow [⋯] the stomach smooth and flat [⋯] breasts drooping [⋯] nipples prominent and hard [⋯] shiny tresses [...] soft and graceful neck and throat. (TMOB, p. 901)

Yet in another description as given below, the gazer, a man, moves his eyes from her head to toe and describes her body parts in connectivity to highlight how well shaped these body parts are. Hence, her body parts are arousing a sexual desire in the gazer.

From the forehead to the eyes and the nose and the lips; from the chin to the neck; from the clavicle to the arms [⋯] from the palm of her hands to her fingers; from the shoulders to the breasts; from the belly to the navel; from below the navel to the hips; from the buttocks to the thighs and calves [⋯] fully in proportion, or well-shaped (TMOB, p. 399)

The description of Amir Bahu as in “her breasts and hips were heavy” (TMOB, p. 571) again highlights the woman’s sensual appeal and influence through her sexual organs. Two other female characters, Jamila and Habiba are also described through their body parts which connote sexuality and passivity at the same time. Based on this analysis, it can be concluded that Faruqi’s (2013) description of his female characters’ body parts substantiates Woldemariam’s (2018) findings that women when fragmented into body parts are described as passive objects.

Women are Seductively Beautiful

Other than representing women’s sexual appeal, the description of females’ body parts in TMOB carries some other meanings as well. For example, the descriptions of Wazir’s face like the “fresh bloom of her face” (TMOB, p. 228), “making her face glimmer with beauty’s luminance” (TMOB, p. 290) and “her face had the same delicate softness” (TMOB, p. 383) express the freshness, beauty, and softness of a woman’s face. Her face is again highlighted for its beauty when Faruqi (2013) describes her face as “prettiest of faces⋯what a lovely visage” (TMOB, p. 384). Anwari is described as a sweet lady in “how sweet how fresh was Bari’s face” (TMOB, p. 217) while Habib-un-Nisa face was “gentle and sophisticated” (TMOB, p. 381). Another female character is described as: “Her color golden brown like the champak flower” (TMOB, p. 571). The comparison of a woman’s color with a flower presents her as a ravishing beauty.

Women are Shy

The description of Jamila and Habiba through their body part “face” shows their shyness where the phrase “the rosy hue” hints at their submissive and shy nature: “two sisters’ faces turned a rosy hue” (TMOB, p. 170). Moreover, the description of red color connotes shyness in women when Faruqi (2013) writes about Wazir “The lobes of her ears, then her brow, then her cheeks blush hot” (TMOB, p. 411). Jamila and Habiba are also described in relation to the red color of their earlobes in the presence of a man as in “their earlobes reddened” (TMOB, p. 166). Wazir’s shyness is described through a description of her feelings like “felt her ear lobes redden (TMOB, p. 288). Faruqi (2013) describes her shyness in relation to how her body parts change their color as he writes “The lobes of her ears, then her brow, then her cheeks blush hot” (TMOB, p. 411).

Women are Delicate / Small

The women are also presented as delicate creatures through their body parts. The descriptions like “her delicate, well-proportioned neck” (TMOB, p. 327), “the delicateness of hands and feet” (TMOB, p. 273) and “the delicate, well-formed face” (TMOB, p. 804) portray the women as weak but beautiful creatures. In “the delicate fingers and supple wrists of Kashmiri girls” (TMOB, p. 73), Faruqi again presents these women through their delicate features. They are described as “their slightly bent backs, made their young breasts prominent, [⋯] their slim necks raised like a deer’s and the alertness of their eyes” (TMOB, p. 161). Jamila and Habiba are also described as “Their faces oval, [⋯] the rounded, well-formed wrists [⋯] a good bit of the legs from the ankles to the knees were deliberately visible [...] their doe- like eyes (TMOB, p.162). Another way to describe men and women differently is that men are described as big while women are described as small. This idea finds its expression in “their fair tiny hands” (TMOB, p.73) when used by Faruqi (2013) in TMOB to refer to women.

Women are Oppressed/Melancholic/Weak

In TMOB, the use of body parts in relation to show the oppressed and melancholic state of the women is also noticed. The description of Wazir’s eyes like “her eyes welled up suddenly” (TMOB, p. 253) and “her tear-filled eyes” (TMOB, p. 315) show her grief that she feels when her children are taken away from her. Again, she is shown to be weak, sensitive, and emotional through another description with a focus on her eyes, face, and arms “her eyes were bright with unshed tears and her face was red with the effort to stop them [⋯] arms lack strength (TMOB, p. 315). Hence, such a description of the body parts presents woman as a weak creature. Other than Wazir, the desert women are also described through a description of their body parts. Their dull eyes and weary faces show their pathetic condition as Faruqi (2013) gives a description of them “their eyes were devoid of even a hint of the moon-glow [...], their faces hidden under a fine veil of dust [...] youth had departed their faces at some uncertain time in the past” (TMOB, p. 160). But the sexual appeal of the tired women is also highlighted when he writes about them as “they were narrow waisted even now, but their breasts and hips lacked the proud tightness” (TMOB, p. 161).

The color of the women’s face is also described to highlight their tough life routine. The description of desert women in relation to their copper-like faces shows this clearly “the women’s faces, tanned like copper, were even darker now because of grieving, their eyes totally down cast” (TMOB, p. 112).

Fragmented Bodies and Men’s Representation

In comparison to women’s fragmented bodies connoting, mostly, their sexuality, the men are not described for the same purpose only through their body parts in TMOB. Contrary to female characters, the fragmentation of male characters highlights their handsome personality, physical and mental strength, their sense of honor and their positive traits. However, in some cases, though less in number men’s body parts are used to highlight their lustful nature. Other than these, the men’s body parts are described in relation to normal routine activities or to exhibit the theme of death, suffering or illness. The following discussion elaborates these ideologies reserved for men with a support of examples from the text:

Men are Handsome

The fragmentation of men’s bodies in TMOB highlights their handsome attractive personality. For example, the character of Mirza Ghalib is described in relation to his physical strength and attractive personality through his different body parts as given in the following excerpt:

His forehead high, his eyes bright and smiling, his chest broad, his wrists wide and his neck upright [⋯] his face was void of a beard [⋯] his brows were thick, his eyelashes long, and his delicately formed lips ⋯ his face so attractive and absorbing (TMOB, p. 278).

Mirza Fakhru is another male whose description shows how men’s body parts are described simply to show their physical features devoid of any sexual appeal:

His face was fully oval, with high cheekbones, the nose long and straight, the neck high and erect. His eyes were jet black, bright [⋯] his complexion was light brown, and his face covered with a longish but pointed beard (TMOB, p. 767).

Furthermore, Navab Shamasuddin is described with the same effect in the text as reproduced in the following extract: “his large eyes were suggestive of his Transoxianian origins. His beard was cut in the Mughal style [⋯] the moustaches were not heavy but prominent” (TMOB, p. 278).

Men are Strong

The description of the male’s body also reveals their physical strength. Navab Mirza’s body is described as “well-developed, well-proportioned, and bigger-than-average body” (TMOB, p. 475). Other than their physical strength, the body part ‘face’ is used to highlight their mental or emotional strength of mind as well. For example, Karim Khan is described as “clouds of pain and regret passed over his face but were soon replaced by gravity and firm determination to act (TMOB, p. 527).

The physical and mental strength possessed by men is also highlighted where they are presented as strong bodied and strong willed through a description of their different body parts. The description of Navab Mirza even when he was a baby is highly fragmented where his different body parts are described to indicate ideals about masculine body and strength. It is important to note that how his different body parts like face, nose, forehead, fingers, wrists and even toes are described in relation to his physical strength in the following example:

The bones of its face were noble, the nose and mouth were well proportioned. Nose was straight and prominent, Chubby cheeks, [⋯] his forehead was quite high, and his eyes were exceptionally large, fingers were long and pointed⋯.his wrists wide and strong, and even his toes were well formed and somewhat longer than usual (TMOB, pp. 472-473).

In another excerpt from TMOB, the writer has highlighted the male’s strength through a description of his body parts like arms and wrists as in “strong muscular arms and broad wrists, [⋯] His large, deep-brown-black eyes [⋯] his long, thin and slightly crooked Turkic nose [⋯] a tiny flare of the nostrils indicated strength of will” (TMOB, p. 629).

Men are Honorable

The other passions reflected through a man’s body parts are his feelings related to his honour, anger, and revenge. Navab Shamsuddin’s feelings of anger and revenge when he got insulted at the hands of William Fraser are highlighted through the state of his body parts as given below:

His cheeks looked sunken; his cheekbones seemed somehow more prominent [⋯] the straight, well-formed nose looked longer and thinner. The proud neck [⋯] seemed to be tense [⋯] the gaunt face [⋯] his fists were clenched (TMOB, p. 507).

Men are Active / Alert

Again, contrary to the description of woman’s face, thighs, stomach in relation to her sexual appeal, the same body parts of the male are described to highlight his active, strong, and alert body as given in following excerpt from TMOB:

Broad and strong of chest [⋯] heavy moustache and beard trimmed [⋯] his young, energetic face [⋯] with a back that was ramrod straight, he had a taut and powerful body; his stomach, abdomen and thighs did not have an ounce of extra muscle, not to speak of any fat anywhere else on his body. This was Karim Khan, Chief of the Hunt to Shamsuddin Ahmad Khan (TMOB, p. 522)

Men are the Providers/Protectors

Another ideology communicated through these body parts is that the men provide shelter and protection to the women. For example, Navab Shamasuddin assures Wazir Khanam that “I can become the strength of your arms” (TMOB, p. 316) which shows that he will protect and defend her. Wazir in response accepts him as her protector and claims: “you nourish me and cherish me by your generosity. God has made your chest wide and sky-kissing like the ramparts of the Haveli” (TMOB, p. 316). The mentioning of body part “chest” in relation to its being wide and sky-kissing like a rampart shows the strength of a man. Hence, a female is weak and needs the protection of the man.

Again, in another context of love making, the Navab assures Wazir his help by saying “If you faint, I will hold you up. After all, why did God create arms and hands” (TMOB, p. 397). The body parts “arms” and “hands” refer to the protection and strength of a man that he can provide to a woman.

Men are engaged in Routine Activities

Other than these ideas, the male body parts are also described in relation to normal routine life activities. For example, Daud and Yakub “oiled their hair, [⋯] scented their beards and necks” (TMOB, p. 169). Likewise, in “they washed their faces, hands and feet” (TMOB, p. 681), the men’s body parts are engaged in normal life routine activity of washing. Likewise, the body part breast when used to describe women appears with sexual connotation but when the breast is mentioned in relation to men it is used to indicate their action i.e., mourning as in they “began to beat their breasts” (TMOB, p. 115). Such a description of body parts engaged in normal life activities was not noted in women’s case. In women’s case such body parts like face, neck, hair, and breasts are always carrying some negative meaning them i.e., presented women as sexual objects to be used by the men.

Men’s Bodies with Theme of Death, Suffering and Sickness

The body parts of Muhammad Yahya when presented in fragments are used to refer to his sickness resulting in his death. Contrary to the description of the female’s body parts used to highlight her sexual appeal, the following excerpt mentions a male’s body parts like his chest, face, forehead, and brow in relation to his pain and suffering:

A wave ran through each and every nerve in his body [⋯] the pain in his chest grew [⋯] his face was much more drawn and paler than usual, with beads of perspiration on his forehead and his brow was knitted with discomfort (TMOB, pp. 137-138)

Likewise, in another example, the lips, eyes, chest, shoulders, and forearms of the same character are described in relation to his painful suffering and feelings resulting from his sickness as narrated by the text “an audible sob escaped his lips, prompted by the pain; his eyes opened. [⋯] Pain was coursing through his chest, his jaws, shoulders, and arm. Even his forearms seemed to be hurting as never before” (TMOB, p. 142).

For example, the description of Daud and Yakub’s complexion as “swarthy and deep brown like their father’s” (TMOB, p. 99) does not connote any sexuality. Likewise, in “Yahya’s color was now pale” (TMOB, p. 140), the pale color does not hint at his melancholic state, some fear or physical weakness. Instead, it announces his approaching death. In another description, the yellow eyes of a man show his anger as in “small yellowish eyes seemed ablaze” (TMOB, p. 175).

Men are Lustful

The men, too, are described, though less in number, in relation to the warmth and sexual desire reflected through their body parts. For example, Navab Shamasuddin’s body parts are described in relation to the awaited fulfillment of his sexual desire when he narrates his state as “my eyes are sleepless, looking forward to your coming, my arms are impatient to clasp you, my mouth will not rest until it touches yours” (TMOB, p. 352). On another occasion, Wazir Khanam admires Navab’s body when the texts narrates how she gazes at his body parts: Her eyes were drinking in the fair and shapely warmth of his shoulder, and breast and neck (TMOB, p. 504).

Other than Navab Shamasuddin, Blake, another male character, is described as fair and brown haired which connotes his appeal and attraction as in “he was very fair and brown haired, and his eyes were small and light brown” (TMOB, p. 203). The brightness of his body is also highlighted which attracts the woman, Wazir Khanam when she praises his body as “how tightly kneaded, how bright, how splendid was his body” (TMOB, p. 330). Moreover, the lustful nature of men is also highlighted through a description of Blake’s gestures as in “Blake’s face would bloom at the sight of her. His every gesture, all his body’s gestures and his affectionate deportment revealed more than mere words that he delighted in her company”(TMOB, p. 215). Likewise, the body parts of William Fraser are also described in such a way that portray him as a man of sexual appeal with sexual desires where his moustaches are described as “reddish brown and thick⋯large, expressive eyes, a well-formed straight nose, and lips a little thicker than usual but attractive[⋯]his eyes revealed a wild glimmer” (TMOB, p. 270).

Conclusion

Based on the above discussion, it can be concluded that both the male and female characters of Faruqi’s (2013) are described through fragmentation but they are marked differently from each other. The positive depiction of men presents an idealized picture of them in relation to their power, authority, strength and masculinity which aligns with the cultural and literary traditions of 19th century India where male characters were usually associated with strength, wisdom, honor and chivalry. In contrast to this ideal picture of the men, women’s sexual appeal and seductive nature is highlighted through their attractive sexual body parts which relegates them to a position of a commodity to satisfy the gaze of men. Hence, Faruqi (2013) portrayal of his men and women characters through their body parts has served to reinforce societal hierarchies and the patriarchal structure of 19th-century Indian society which often idealizes men as brave warriors, warriors, poets, intellectuals and heads of the families while women are portrayed through a lens of aestheticization and desirability. Table 1 presents an overview of how different ideologies are constructed attached to each gender with respect to the description their bodies/body parts. women are described only negatively through their fragmented body parts but Faruqi’s (2013) description of men through their body or fragmented body parts draws a balanced picture of them where they possess all the qualities of head and heart. When probing into negative traits, it is observed that women are presented negatively in all the cases. The men, on the other hand, are shown positively in most of the cases and the only negative trait highlighted in them is their being lustful. Other than this, men’s body parts are used in a neutral way where these function in a neutral way i.e., showing routine activities or processes.

The researchers conclude that the bodies of the female characters in TMOB are presented not only in fragments but also as a whole where both cases are utilized to present them merely sexual objects. Moreover, what this study finds different from the previous findings (Mills, 1995; Wulandari, 2018) is that the bodies of the men are also described through their body parts but with a different purpose to present them stereotypically in a positive way most of the time as given in Table 1. The researchers have also found feminist stylistic framework very helpful for carrying out linguistic analysis of a literary text from gender perspective. The researchers recommend that this model can be utilized in future studies as well to study both the literary and non- literary texts to unravel a writer’s attitude towards gender description.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prince Sultan University for funding this research project under the Language and Communication Research Lab grant [RL-CH-2019/9/1].

References

- Achili, N., & Rahil, F. (2025). A Corpus Stylistic Analysis of Jamaica Kincaid’s “Lucy” (1990) Novel. Retrieved from https://aleph.edinum.org/13672

-

Al-Nakeeb, O. A. M. S. (2018). Fragmentation of the fe/male characters in Final Flight from Sanaa: A corpus-based feminist stylistic analysis. International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature, 7(3), 221–230.

[https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.7n.3p.221]

-

Alonso, A. (1942). The stylistic interpretation of literary texts. Modern Language Notes, 57(7), 489–496. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2910620

[https://doi.org/10.2307/2910620]

- Alvi, M. (2016). A Manual for Selecting Sampling Techniques in Research. Retrieved from. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/70218/1/

-

Alzamil, W. A., Ibrahem, U. M., Alabdulkareem, R., Almusfir, M. F., ALqasem, M. A., Ahmed, E. M., & Alkasabi, M. T. (2023). Factorial validity of the self-compassion scale among female University students: A comparative study between Saudi and Egyptian cultures. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 27(6), 88–100. Retrieved from https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajrh/article/view/260914

[https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1545536/v1]

- Ansar, M., & Hussain, M. (2025). Aestheticization of female body: Narrative Intrusion of the Unnecessary Description in The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy. Educalitra: English Education, Linguistics, and Literature Journal, 4(1), 44–54.

-

Anwar, B., Kayani, A. I., & Ramiz, M. (2024). Reversed Gender Roles and Linguistic Choices: A Transitivity Analysis of Gender Disparities in Ali’s The Stone Woman. Journal of Development and Social Sciences, 5(2), 101–111.

[https://doi.org/10.47205/jdss.2024(5-II)11]

-

Anwar, B., Kayani, A. I., & Iram, A. (2023). Linguistic Sexism at Word Level in Ali’s The Book of Saladin: A Feminist Stylistic Perspective. Journal of Development and Social Sciences, 4(4), 658–671.

[https://doi.org/10.47205/jdss.2023(4-IV)58]

-

Arikan, S. (2016). Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber: A Feminist Stylistic Approach. Fırat Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 26(2), 117–130.

[https://doi.org/10.18069/firatsbed.346908]

- Ashimbuli, N. L. (2022). Language and gender in My Heart in Your Hands: Poems from Namibia: A Feminist Stylistic Approach [Doctoral dissertation, Namibia University of Science and Technology].https://ir.nust.na/handle/10628/904

- Atoke, R. B. (2021). A Feminist Stylistic Analysis of Women Portrayal in Selected Nigerian Novels [Doctoral dissertation, Kwara State University, Nigeria].https://www.proquest.com/openview/98725c04317e531b590a10ae0edb36ce/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2026366&diss=y

- Bado, D. A. (2021). Women Representation in Indonesian and American Marriage Movies: A Feminist Stylistics Analysis [Doctoral dissertation, Universitas Islam Negeri Maulana Malik Ibrahim]. http://etheses.uin-malang.ac.id/51565/1/17320153.pdf

-

Brown, C. A. (2012). The Black Female Body in American Literature and Art: Performing Identity. New York: Routledge.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203113981]

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social Research Methods. Oxford University Press.

-

Coffey, J. (2013). Bodies, Body work and Gender: Exploring a Deleuzian Approach. Journal of Gender Studies, 22(1), 3–16.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2012.714076]

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2016). Qualitative inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. Sage.

-

Culpeper, J., & Fernandez-Quintanilla, C. (2017). Fictional characterisation. Pragmatics of Fiction, 12, 93–128.

[https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110431094-004]

- Darweesh, A. D., & Ghayadh, H. H. (2016). Investigating Feminist Tendency in Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale” in terms of Sara Mills’ Model. A Feminist Stylistic Study. British Journal of English Linguistics, 4(3), 21–34.

- David, N. D. (2020). A Feminist Stylistics Study of the Representation of Women in The Lion and the Jewel and The Trials of Brother Jero [Doctoral dissertation, Namibia University of Science and Technology (NUST)]. Retrieved from https://ir.nust.na/items/ce7b3614-98b4-4eb3-b376-1924f814a7fe

- Denopra, M. M. P. (2012). A Feminist Stylistic Analysis of Selected Short Stories by Kerima Polotan-Tuvera. Unpublished master thesis. Diliman: University of the Philippines.

-

Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The Qualitative Content Analysis Process. Journal of advanced nursing, 62(1), 107–115.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x]

- Fārūqī, S. (2013). The Mirror of Beauty. Hamish Hamilton.

-

Green, K., & LeBihan, J. (2006). Critical Theory and Practice: A Course Book. Taylor & Francis.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203130100]

- Hama, B. S. (2017). Self-Presentation in Selected Poems of Maya Angelou A Feminist Stylistics Study. International Review of Social Sciences, 5(2), 123–128. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331608138

-

Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687]

- Innes-Parker, C. (1995). Fragmentation and reconstruction: Images of the female body in Ancrene Wisse and the Katherine Group. Comitatus: A Journal of Meideval and Renaissance Studies, 26(1), 27–52.

-

Isti'anah, A. (2019). Transitivity Analysis of Afghan Women in Asne Seierstad's The Bookseller of Kabul. LiNGUA, 14(2).

[https://doi.org/10.18860/ling.v14i2.6966]

-

Jeffries, L. (2007). Textual Construction of the Female Body: A Critical Discourse Approach. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

[https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230593626]

- Jespersen, O. (1922). Language: Into Nature, Development and Origin. Allen and Unwin.

- June, P. B. (2010). The Fragmented Female Body and Identity: The Postmodern, Feminist, and Multiethnic Writings of Toni Morrison, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Phyllis Alesia Perry, Gayl Jones, Emma Pérez, Paula Gunn Allen, and Kathy Acker (Vol. 56). Peter Lang.

-

Kang, C., & Wu, X. (2015). The Transitivity System and Thematic Meaning: a Feminist-Stylistics Approach to Lawrence's Lady Chatterley's Lover. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 5(6), 1200–1205.

[https://doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0506.11]

- Kappeler, S. (1986). The Pornography of Representation. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Katrak, K. (2006). The Politics of the Female Body: postcolonial women writers. Rutgers University Press.

-

Kayani, A. I., Anwar, B., Shafi, S., & Ali, S. (2023). Representation Of Indian Woman and Man: A Feminist Stylistic Analysis of Transitivity Choices in Faruqi’s The Mirror Of Beauty. Journal of Namibian Studies: History Politics Culture, 34, 2855–2881.

[https://doi.org/10.59670/5cxfp622]

- Kayani, A. I., & Anwar, B. (2022). Fragmentation and Gender Representation: A Feminist Stylistic Analysis of Faruqi’s The Mirror of Beauty. Journal of Gender and Social Issues, 21(1), 29–44. https://jgsi.fjwu.edu.pk/jgsi/article/view/335/263

-

Kayani, A. I., & Anwar, B. (2022). Transitivity choices and gender representation: A feminist stylistic analysis of Ali’s “The Book of Saladin”. Journal of Arts & Social Sciences, 9(1), 13–25.

[https://doi.org/10.46662/jass.v9i1.208]

- Khan, L. A., & Ateeq, A. (2017). Construction of gendered identities through matrimonial advertisements in Pakistani English and Urdu newspapers: A critical discourse analysis. Almas Urdu Research Journal, 19(1). http://almas.salu.edu.pk/index.php/ALMAS/article/view/52/46

-

Khazai, S., Beyad, M. S., & Ghorban Sabbagh, M. R. (2016). A Feminist-Stylistic Analysis of Discourse and Power Relations in Gaskell’s North and South based on Searle’s Theory of Speech Acts. Language and Translation Studies (LTS), 49(2), 23–44.

[https://doi.org/10.22067/lts.v49i2.59693]

-

Kibiswa, N. K. (2019). Directed Qualitative Content Analysis (DQlCA): A Tool for Conflict Analysis. The Qualitative Report, 24(8), 2059–2079.

[https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2019.3778]

-

Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology. Sage.

[https://doi.org/10.4135/9781071878781]

-

Laine, T., & Watson, G. (2014). Linguistic sexism in The Times-A diachronic study. International Journal of English Linguistics, 4(3), 1.

[https://doi.org/10.5539/ijel.v4n3p1]

-

Lakoff, R. (1975). Linguistic Theory and the Real World. Language Learning, 25(2), 309–338.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-1770.1975.tb00249.x]

-

Manyak, P. C., & Manyak, A. M. (2021). Literary analysis and writing: an integrated instructional routine. The Reading Teacher, 74(4), 395–405.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1959]

- Mayring, P. (2004). Qualitative content analysis. A companion to qualitative research, 1(2), 159–176.

- Mills, S. (1995). Feminist Stylistics. Routledge.

-

Imran, M., Tilwani, S. A., & Morve Roshan, K. (2023). An answer to Spivak’s can the subaltern speak? A study of marginalized women’s autobiographies. Contemporary Voice of Dalit.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/2455328X231166999]

- Morguson, A. (2013). All the pieces matter: Fragmentation-as-agency in the novels of Edwidge Danticat, Michelle Cliff, and Shani Mootoo (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarworks.indianapolis.iu.edu/items/c201a5da-8241-4833-a486-bb8a4f8d80dd

-

Page, R. (2010). New Challenges for Feminist Stylistics. The Case of Girl with a One Track Mind. Journal of Literary Research, 4(1), 81–97.

[https://doi.org/10.1515/jlt.2010.005]

- Qayyum A. (2021). Gender Stereotyping in 20th Century Short Fiction: A Study in Feminist Stylistics. Unpublished PhD thesis. Department of English and Applied Linguistics, University of Peshawar, Pakistan. http://prr.hec.gov.pk/jspui/handle/123456789/18998

-

Qayyum, A., Rahman, M., & Nisar, H. G. (2019). A Feminist Stylistic Analysis of Characterization in Doris Lessing’s A Woman on a Roof. Global Regional Review, 4(3), 309–316.

[https://doi.org/10.31703/grr.2019(IV-III).35]

-

Radzi, N. S. M., & Musa, M. (2017). Beauty ideals, Myths and Sexisms: A Feminist Stylistic Analysis of Female Representations in Cosmetic Names. GEMA Online Journal of Language Studies, 17(1), 21–38. http://ejournal.ukm.my/gema/issue/view/897

[https://doi.org/10.17576/gema-2017-1701-02]

-

Raza, A., Rashid, S. & Malik, S. (2022). Cultural violence and gender identities: A feminist post-structural discourse analysis of This House of Clay and Water. 3 L: Language, Linguistics, Literature. 28(4), 124–136.

[https://doi.org/10.17576/3L-2022-2804-09]

- Riaz, I. & Tehseem, T. (2015). Exploring the Sexual Portrayal of Women in Media Adverts: A Feministic Perspective. International Journal of Advanced Information in Arts Science & Management, 3(3), 11–28.

-

Rennick, S., Clinton, M., Ioannidou, E., Oh, L., Clooney, C., Healy, E., & Roberts, S. G. (2023). Gender bias in video game dialogue. Royal Society Open Science, 10(5), 1–12.

[https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.221095]

- Saadia, M. H., Bano, S., & Tabassum, M. F. (2015). Stylistic Analysis of a Short Story “The Happy Prince”. Science International-Lahore, 27(2), 1539–1544.

- Savinainen, R. (2001). Gender-specific Features of Male/Female Interaction in a Popular Romantic Novel by Barbara Cartland. [A Pro Gradu Thesis, University of Jyvaskyla, Finland] Retrieved from http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi:jyu-2001867069

- Sher, M., & Saleem, A. (2023). Linguistic Sexism in ‘Rishta Culture’of Peshawar: A Feminist Stylistic Analysis of Matrimonial Advertisements in Newspapers. Journal of Academic Research for Humanities, 3(2), 154–167.

-

SooHoo, J. (2022). A Systematic Review of Sexism in Video Games. PsyArXiv. Retrieved from

[https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/xrh36]

-

Supriyadi, S. (2014). Masculine Language in Indonesian Novels: A Feminist Stylistic Approach on Belenggu and Pengakuan Pariyem. Humaniora, 26(2), 225–234.

[https://doi.org/10.22146/jh.5244]

-

Ufot, B. G. (2012). Feminist Stylistics: A Lexico-Grammatical Study of the Female Sentence in Austen's Pride and Prejudice and Hume-Sotomi's The General's Wife. Theory & Practice in Language Studies, 2(12), 2460–2470.

[https://doi.org/10.4304/tpls.2.12.2460-2470]

-

Verma, C., & Dahiya, S. (2016). Gender Difference towards Information and Communication Technology Awareness in Indian Universities. Springer Plus, 5(1), 370–378.

[https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-2003-1]

-

White, M. D., Marsh, E. E., Marsh, E. E., & White, M. D. (2006). Content analysis: A flexible methodology. Library trends, 55(1), 22–45. Retrieved from https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/1/article/202361/55.1white

[https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2006.0053]

-

Woldemariam, M. (2018). Insurgent fragmentation in the Horn of Africa: Rebellion and its Discontents. Cambridge University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108525657]

- Wulandari, S. (2018). A Feminist Stylistic Analysis in Laurie Halse Anderson’s Novel Speak, Unpublished Master thesis, University of Sumetara Utara. Retrieved from https://repositori.usu.ac.id/handle/123456789/7323

Biographical Note: Asma Iqbal Kayani is an Assistant Professor in the Department of English at Mirpur University of Science and Technology (MUST), Mirpur, Azad Kashmir. She has 17 years of teaching experience and holds a Ph.D. in English from the University of Gujrat, Pakistan. Her doctoral research focused on language and gender, analyzing linguistic choices in the writings of Asian novelists through a feminist stylistic framework from a sexist perspective. Her research interests include Gender Studies, Sociolinguistics, and Corpus Studies. Email: asma.eng@must.edu.pk

Biographical Note: Behzad Anwar is an Associate Professor of English at the University of Gujrat, Pakistan, with over 15 years of teaching and research experience at various institutions. He holds a Ph.D. in English from Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, and has served as an academic visitor at the University of Birmingham, UK. Dr. Anwar has presented numerous research papers at national and international conferences. His research interests include World Englishes, Sociolinguistics, and Corpus Studies, with a recent focus on language use and gender analysis. Email: behzad.anwar@uog.edu.pk

Biographical Note: Dina Abdel Salam El-Dakhs is the Chair of the Linguistics and Translation Department and the Leader of the Language and Communication Research Lab at the College of Humanities and Sciences, Prince Sultan University. She has extensive teaching and coordination experience in Linguistics, Translation and Language Studies programs. Her research interests are Pragmatics, Discourse Analysis, Psycholinguistics and Second Language Education. Email: ddakhs@psu.edu.sa

Biographical Note: Muhammad Younas received the Ph.D. degree in higher education from Soochow University, China. He is currently a Researcher with the Language and Communication Research Laboratory, Prince Sultan University, Saudi Arabia. His research interests include artificial intelligence in education, language teacher education, CALL, e-learning in higher education, technology-enhanced learning, MALL, and virtual learning environments (VLE). He received the Jiangsu Province Outstanding International Researcher Award from Soochow University. Email: myounas@psu.edu.sa

Biographical Note: Islander Ismayil, Uyghur, Doctor of Education, associate researcher of Xinjiang Institute of Education; The research direction focuses on educational technology innovation and teaching practice, regional educational informatization, educational big data, information technology and curriculum integration, and artificial intelligence education application. He went to Peking University to study information teaching and served as a visiting scholar in Beijing Normal University, participating in cutting-edge research in the field of education. Email: iskander_ismayil@hotmail.com