Women, Public Space, and Mutual Aid in Rural China

As rural Chinese women’s social networks are restricted by traditional, patriarchal gender norms, and poor geography and infrastructure, there is little chance for these women to build new social contacts or even to maintain existing networks. Based on qualitative data collected through participant observation, focus groups, and interviews in H village, this research indicates that public spaces provide rural women a platform for the enhancement of social networks through frequent interaction with other participants. It is interesting to find that strengthened relations and established social networks formed in public spaces positively contribute to village women’s daily lives, especially in the form of mutual aid when rural women need help during illness, need to borrow money for building a house, or need an extra hand to finish the harvest. Thus, through public spaces, rural women experience higher levels of mutual aid provided by the actors in their social networks, who can even replace the function of kinship to some extent by acting as a “functional alternative.” For instance, during the agricultural busy period, friends from public spaces can help left-behind women with the paddy harvest, substituting for the out-migrating men who would have customarily performed this function.

Keywords:

Women, public space, social networks, mutual aid, rural ChinaIntroduction

Habermas (1991) defines “public space” as the external manifestation of the “public sphere,” or the various autonomous public gathering places and institutions (cafeterias, salons, etc.). Analyzing 218 articles and books on public space published between 1945 and 1998, Staeheli and Mitchell (2007) point out that a large number of studies identify public space by its physical aspects, such as streets, parks, and squares. Generally speaking, scholars tend to study public space as a physical site, with a focus on its impact on culture and political discourse. Firstly, public spaces are common sites for cultural sharing, constructing, and exchanging among people (Abaza, 2001; Amin, 2008, Low, 1997). For example, public spaces have a significant positive impact on the transmission of traditional Chinese culture (Zhou, 2003; Wang, 1998). Secondly, public spaces are the sites essential for citizens’ political activities (Hartley, 1992; Howell, 1993; Melucci & Avritzer, 2000; Irazabal, 2008). For instance, Rowe (1990), a historian of China, conceives the notion of “public” (gong) in its political sense, such as the role for political participation.

While public space has been the subject of extensive research, it is rare to find studies of public space from a gender perspective. This is especially true with regard to the role of public space for women in rural communities with poor infrastructure, a traditional, patriarchal division of labor, and limited social networks. This article seeks to fill this research gap by examining public spaces in rural China. In this research, public spaces refer to places that are open and freely accessible to people (including venues for special events), with face-to-face interaction as an essential element. Although recent studies have included the virtual world as a form of public space due to the rise of Information and Communications Technologies(ICTs) (Zheng & Wu, 2005; Zheng, 2007; Li, 2010), this research focuses on physical rather than online public spaces, since rural residents in China, particularly women, have little access to the Internet. In rural China, women’ daily lives consist mainly of farm work, domestic chores, and daily contacts. Public spaces provide them with venues for gathering and other activities, and they think of public space as an essential part of daily life, as it allows them to exchange or receive useful resources such as information, goods, knowledge, and entertainment (Wang, 2005; Cao, 2005).

Through an in-depth analysis of qualitative data, this research finds public spaces have a remarkable impact on rural women’s social networks. Not only do they strengthen women’s existing networks when they meet up with old friends, but they also extend their social networks through building new friendships with strangers. Such connections are vital for village women since it is difficult for them to create new social relationships in rural communities. Their social networks are limited to inherited kinship or geographic relationships such as those among families, relatives and neighbors (Fei, 1992). There is little chance for rural women to enhance their social networks with contacts outside of their hometown. Firstly, the culture of the Chinese patriarchal family constrains the household division of labor in rural China; women are supposed to stay in their villages doing domestic work and taking care of children and the elderly. Secondly, because many villages are located in remote areas with very little infrastructure, there are few, if any, roads that support motorized transportation. Many rural women have never even visited the centre of township, let alone a city.

Therefore, rural women, living in relatively sealed and isolated communities, have little opportunity to expand their social networks beyond kinship and geographic relationships. However, public spaces in villages do provide them a platform for the enhancement of social networks through frequent interaction with other participants in these public spaces. Utilizing qualitative data, this research explores the impact of public spaces on rural women’s social networks. The focus is on the ways in which these social networks can provide mutual aid, especially during important events such as building a house, harvesting crops, and dealing with poor health or immobility. The findings from this research indicate that through the relationships they establish and maintain in public spaces, rural women experience higher levels of mutual aid provided by the actors in their social networks.

Data Collection

The research site is “H village”, located in a mountainous area in inland China. H village is a collection of several clusters of houses with a total population of 2,510 people, of which 1,594 are female. Due to the climate and terrain, it is difficult for these peasants to sustain a livelihood by depending on farm activities (the cultivated area per capita is 0.057 ha). Villagers prefer to migrate to cities for employment. The number of out-migrants is 650, mainly middle-aged men, which leaves a large number of women in the village, referred to in China as “left-behind women.”1

In 2006, I collected data in H village through participant observation, focus group discussions and semi-structured interviews. Each of these methods brings its own advantages to this research: participant observation provides me a vivid, direct and concise understanding of its public spaces; focus group discussions help me grasp divergences and similarities among participants; and semi-structured, one-on-one interviews offer me the opportunity to learn about interviewees’ individual experiences in detail.

Participant observation is a strategy of reflexive learning, not a single method of observing. “As its name suggests, participant observation demands firsthand involvement in the social world chosen for study” (Marshall & Rossman, 2006, p. 100). The researcher can be close with a group and its practices through an intensive involvement with people in their natural environment. During the fieldwork, I engaged in participant observation in a number of public spaces, including a church, a temple, several washing spots, and a teahouse. To be more specific, I went to the Christian church every Sunday, and I lived with the female Buddhists for two weeks in the temple. I did my laundry in various washing spots every morning, visited the teahouse seven times, and participated in different activities there.

A focus group discussion consists of a group of members who have some similar characteristics (Krueger & Casey, 2000); in this case, women that visit one particular public space and discuss familiar issues. Since most women in rural China tend to be shy and introverted, they are encouraged by each other to participate during the focus group discussion, and they are open to talking with other group members in an interactive setting. I organized five focus group discussions of 5-6 women each, in the church, the temple, a grocery store, the square and a washing spot respectively. It is worth noting that the participant observation helped me to select various candidates to invite to the focus group discussions.

Semi-structured interviews are flexible, allowing new questions to be created during the interview as a result of what the interviewee says (Lindlof & Taylor, 2002). Thirty interviews were conducted in total, 10 interviews with local “elites” and 20 interviews with women participating in different public spaces. First, I conducted interviews with elites, key figures within the respective public spaces I studied, as well as one of the township leaders and one of the village leaders. There are several advantages to elite interviewing. For one, elites have a good overall view of their organization (or in this case, their public space), and secondly, elites know the histories and plans of their organization from their particular perspective (Marshall & Rossman, 2006). After interviewing the elites, general information data were collected about the different public spaces and the people that spent time in them. Based on this information, as well as earlier participant observation and focus group discussions, 20 “representative female members” of public spaces were selected as interviewees for this research. These representative members were women who enhanced their social networks through public spaces, and in turn, either received help from other members or offered help to other members. The number of interviews of members of any one public space varied from two to three. For example, three interviews were conducted with participants that visited the temple, while two interviews were held with those frequenting the teahouse.

Public Spaces in H Village

In H village, there are eight kinds of public spaces: the village square, the teahouse, several washing spots, several grocery stores, a Buddhist temple, a Christian church and different venues for weddings and sports meetings. Based on their main functions, public spaces were categorized into four main types: 1) “daily life public spaces” include sites such as washing spots and grocery stores; 2) “recreational public spaces” such as the village square and the tea house address entertainment and leisure needs; 3) “religious public spaces” consist of buildings for religious worship; and 4) “event-based public spaces” are venues for weddings, sporting events, etc., which are temporary and not fixed.

Rural women in H village frequent these public spaces not only to perform domestic chores, practice their religion, or attend a certain event (Wu, 2002; Zhou, 2003), but also to pursue leisure and entertainment opportunities. Because of the poor level of infrastructure in rural China, peasants in underdeveloped regions do not have access to the Internet and sometimes even television. They are more limited in their means of entertainment as compared to urban women; thus, they go to public spaces for leisure. For example, even if some women don’t need to buy anything, they will visit the grocery store since they have become accustomed to chatting with the female shopkeeper. Additionally, women in H village can find an emotional substitute by going to public spaces: since so many men migrate to larger cities in search of employment, left-behind women visit public spaces simply to cure their loneliness. In this case, public spaces are beneficial to their emotional health (DTLR, 2002). A 58-year-old woman, Mrs. Zhou, describes her experience as follows:

Both my husband and my son are migrant workers in Beijing and come back once a year during the Chinese New Year holidays. I am alone at home and miss them very much. One day, when I walked past the square, I heard some laughing from several women who were the same age as me, so I walked up to them and chatted with them. I found out most of them were also left-behind women. It is easy for us to understand each other and share similar experiences. Afterwards, I began to go to the square frequently. Although I have to walk about half an hour to get there from my home, I like to be there, and for me, it is the happiest time of the day since I don’t feel lonely anymore.

Daily Life Public Spaces

There are two kinds of daily life public spaces in H village: the first are the various washing spots and the other are the local grocery stores. The level at which these demands can be met are rather limited in rural China compared to urban regions; for example, urban women can easily reach various markets and malls for daily life demands.

Since only around one fifth of the households in the village have access to running water, in 2005, the village committee (the lowest administrative level) decided to build several washing spots around the village to facilitate residents’ doing the laundry. Every morning from 4:00 am to 9:00 am, some women wash their clothes in a nearby washing spot while a few others go there in the afternoon. These washing spots are busiest during the summer (see Figure 1).

Although most of the women live near each other and thus have met regularly before, their relationships are nonetheless becoming more intimate due to the regular washing of clothes together at particular washing spots. They chat or make jokes with each other, and the washing spots are full of laughter. As one woman put it, “As no men are present normally, we feel free to chat about different topics exclusively among women, such as cooking, clothes, hairstyles, etc.” Most women agree that because of the interaction in this public space not only can they perform their domestic work but also they are able to find some happiness while they do so. For this reason, even some of the women who have running water in their house prefer to launder their clothing at the washing spot instead so as not miss this social aspect. Few men come to the washing spots because most rural Chinese have a traditional view of gender roles: women should take care of domestic affairs (inner), while men should earn money for the family’s livelihood (outer). Thus, if a man were to wash clothes in the public space of the washing spot, others might frown upon or talk about it.

The local grocery store is perhaps the most indispensable daily life place for peasants in H village. Because there is no market in the village, women buy small amounts of daily necessities and snacks at these grocery stores. Through my observation, it is clear that the grocery stores, or more precisely the roads on which they are located, are some of the most popular public spaces in the village. For example, dozens of local residents (a mix of both women and men) get together at grocery stores in the evening, not for purchasing groceries but simply for leisure, especially in the summertime. Because of the lack of air conditioning or fans in most houses, people prefer to go out after dinner, as it is much cooler outside (see Figure 2).

While there, men dominate the conversion, talking about national or regional issues and sports. Few women participate in these discussions. Most are quiet, and some engage in small talk, which tends to focus on domestic affairs and gossip. When men are present, women have to pay special attention to their behavior and words; thus, they are not as open and free as they are at the washing spots, where all the participants are women. One woman articulated the difference, “I can talk and laugh loudly at the washing spots, while here, because there are a few men around, I need to control my voice and try to be quiet, which is the social standard for a good woman.” Further, the women are generally uninterested in the men's topics of conversation. Women have little to no knowledge about these matters due to their low educational background, limited access to mass media and the fact that their social identities derive from their domestically oriented social roles as housekeepers and cooks. As one woman commented, “Men like to talk about different games such as football and table tennis, but I do not know anything about these games such as the rules or the famous players, and I do not care about which athletes won the championship either.”

Western scholars emphasize the fact that public spaces have positive impacts on people’s political values; for instance, people can engage in free speech in public spaces and share their political interests with other social groups, processes that are important for democracy (Low & Smith, 2006; Sorkin, 1992; Kohn, 2004; Mcbride, 2005). However, this research shows this function of public spaces may not apply to women in rural China, not only because they lack a political consciousness, as noted above, but also because the Chinese state, as a non-electoral regime, dominates the citizen’s political ideology and Chinese citizens are not yet free to express their political beliefs publicly (Shi, 1997; Liu, 2000, p. 55).

Finally, the grocery store has a communication function. Due to the high levels of men’s out-migration from H village, there is a need for a regular means of communication between husbands and wives. In this case, they rely on telephone. However, only a few households have a telephone at home; thus, they regard the grocery store telephone as a public telephone. It is a convenient site for women-left-behind to communicate with their out-migrated husbands.

Recreational Public Spaces

Recreational public spaces exist to fulfill women’s needs for a place to go for leisure and entertainment. Women prefer to spend their spare time chatting or engaging in some form of physical exercise. These activities can be performed both indoors and outdoors, depending on which public spaces are available. In H village, there are two kinds of recreational public spaces: the village square and the teahouse.

In 2005, the village committee built a square for the peasants’ leisure on what used to be an empty plot of land. Although this location is rather far away from where most peasants’ live, it was the only piece of flat land available in the mountainous area. When the square was finished, some active women in H village decided that they wanted their life to be more colorful and rather spontaneously organized themselves into a dance group.

In the evening, the square is used by the dance group sometimes, mainly made up of elderly women practicing a traditional Chinese dance called “Yangko” (see Figure 3). We can see that the square, as a public space, provides a site for rural women to transmit traditional culture by practicing Yangko. All of the group’s members expressed how glad they are to be able to carry forward this traditional form of dance. One young participant said, “I heard from my mother and my grandma about Yangko, which is not popular nowadays for my generation. As the youngest participant in the group, I will try my best to practice and preserve it.” Participants truly enjoy Yangko, but they receive other benefits as well. Not only do members learn and practice the dance, but they also cooperate with other group members, reinforcing a sense of teamwork. These group activities have also led to the formation of new and strong friendships. Besides those who practice Yangko, some women go to the town square for relaxation, to sit in the square, chat with each other and watch the dance.

In addition to the town square, in 2005, the village committee decided to create another public space where people could meet and enjoy themselves. The location was a vacant old house that used to belong to a local property owner before the revolution. After renovation, the building was immediately put to use and quickly dubbed “the teahouse” by locals. The teahouse offers visitors the opportunity to play games, such as cards and mahjong, activities that most women enjoy during the agricultural slack time.

Recently the teahouse has also become a space for several collective activities. Upon acquiring a movie projector, the village committee started to organize open-air movie showings in the teahouse at least once a year. Since there is no cinema in H village, and as noted, most women have never been out of H village, the teahouse offers women the experience of watching a movie for the first time. One 75-year-old woman told me, “I never imaged that I would have a chance to watch a movie in my lifetime; I am very happy with such a public service.” Additionally, the village committee has now started to organize public information campaigns in the teahouse, on the swine flu pandemic, for example, since most women lack healthcare knowledge.

Religious Public Spaces

It is well known that religion is unpopular in China. Being religious is uncommon and going to religious public spaces is unusual (Zhang, Conwell, Zhou, & Jiang, 2004; Jaschok & Shui, 2011). There are however, a number different religious buildings and spaces throughout the country: those subsidized by the government; those sponsored by private funding such as the financial contributions of wealthy believers; and those where believers gather that are regarded as unofficial or underground by the Chinese government. The last form is very common in rural China. In H village, religious public spaces include a Buddhist temple built with private funding and a Christian church (“house church”) situated in one of the member’s living rooms.

The local Buddhist temple was built in 1989 by Master Yirong, a rather famous Buddhist in the region. As is the custom in China, peasants visit the temple for worship according to the lunar calendar, which means that they will visit the temple on the first and fifteenth day of each lunar month, as well as on the birthday of Buddha. Most visitors are from H village, although a handful comes from nearby villages. A large percentage of these visitors are female.

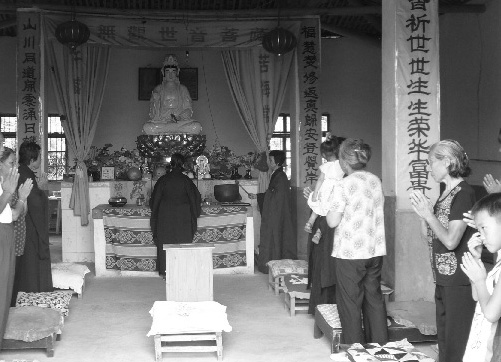

Typically, temple visitors spend an entire day in the temple. Because it is located on the top of a mountain, it takes quite a while to get there. The Buddhists leave their homes right after breakfast, as the walk up to the top of the mountain takes two or three hours. Most arrive before 10:00 am, at which time the Buddhists will start their worship by burning incense and worshipping Buddha (see Figure 4). At 12:00 pm, Buddhists will pool the rice and vegetables they have brought with them and then cook and eat together. After lunch, Buddhists spend their time chatting and relaxing until around 3:00 pm, when they repeat the morning worship ceremony. Once the afternoon ceremony is concluded, they travel back home. While some temple members travel with friends or family, most come alone. The women visiting the temple generally are not acquainted beforehand but eventually become very familiar with each other through their semimonthly visits to the temple. One female Buddhist noted, “Due to regular worship in the temple, I get to meet lots of other Buddhists. I even know around 20 persons’ names, and three of them are my best friends now.” The social networks established through visiting religious spaces complement rural women’s existing networks.

Due to lack of financial support, there is no formal church building either in or nearby the village. Thus, unlike the temple, the local Christian church is not quite as easy to identify as a religious public space, as people gather in one of the member’s living rooms (Figure 5). Every Sunday, around 20 to 30 Christians come here to pray, although occasionally there can be as many as 70. Women account for about 75 percent of the attendees. The oldest is over 80 years old, while the youngest are toddlers and children who go to church with their mothers. These Christians spend the entire Sunday at church on a weekly basis. Throughout the day, they participate in different activities organized by a local retired teacher, whom people call Pastor Chen. These activities include Bible reading, singing, and lunch. As most of the elderly women are illiterate, they simply listen to Pastor Chen reading and explaining the Bible, generally from the New Testament.

Similar to the temple members, these churchgoers are generally not friends or relatives before meeting each other every week in church, but because of their weekly meetings, they know each other well, and their social networks expand. As Mrs. Zhang described,

I was from another village and married a local peasant in H village in 2005. Afterwards, I settled in H village and went to church weekly. At the beginning, I did not know any other Christians in the church. But after a few weeks, I knew everyone and we became familiar with each other very quickly.

Mrs. Zhang can make so many new friends due to the intensive and frequent interaction at the church. In addition, because the church is in a living room, the limited space prompts attendees’ close interaction.

Event-based Public Spaces

Event-based public spaces are temporarily created by certain occasions. In H village, there are two kinds of event-based public spaces: wedding sites and the Peasants’ Games site. The main characteristic of an event-based public space is that the physical place is not fixed but changes according to different activities and actors. Generally, the public space disappears at the end of the event.

Since most of the young men in the village have migrated to cities and come back only once every year during the lunar New Year, most weddings are held during this period. Weddings are generally held in the house of the bride’s or the groom’s parents. Although the house is a private space, for the duration of the event the peasants in the village regard it as a public space in both the way they want to use it and the way they think about it (Staeheli & Mitchell, 2006). Therefore, everyone, even strangers, can attend a wedding.

In rural China, a wedding is regarded as the most important event for a family, and hundreds of guests (typically three to eight hundred) will attend the wedding. The host is expected to prepare a nice lunch for these guests, with at least twelve dishes, including pork, chicken, beef, fish and duck. Both the number of guests and dishes depends on the wealth of the family that hosts the wedding. The event usually lasts for two days, during which friends, neighbors, relatives and (business) acquaintances will attend the wedding and give gifts, commonly money. While most people simply attend the event, close female friends and relatives are invited to help with preparations for the wedding, especially to prepare the lavish lunch.

The wedding is an especially important social event; because guests have a wide range of different relationships with the bride or groom’s family, they are unlikely to be acquainted with each other. Additionally, the guests are likely to come from various villages, cities and regions outside of the couple’s village. Because of this, throughout the wedding, guests have the opportunity to expand their social networks into areas that otherwise would have been closed to them. People find themselves getting to know extended family or guests from nearby villages as well as from far away cities, with varying educational backgrounds, socio-economic statuses and professions. For example, while one of the bride’s friends might not know one of the groom’s cousins prior to the event, the wedding creates a space for them to get to know each other, and build new social contacts. However, although one can make valuable social contacts throughout the event, their frequency tends to be too low to build strong social relationships.

Every year, the township (an administrative level higher than village) organizes the “Peasants’ Games,” which take place over the course of an entire day. Athletes from different villages vie for the prospect of prize money. The event consists of various competitions, such as tug-of-war, table tennis, chess, slow bicycle ride, 30-meter kangaroo jump, 30-meter running on sand, and 30-meter running across the river bridge. Athletes are divided into women and men’s groups and can choose to participate in one or multiple competitions.

In 2006, twenty-one peasants from H village signed up as athletes, while a hundred more, mainly women, attended the event to cheer their fellow villagers on from the sidelines. The village committee was responsible for organizing the attendance of any villagers as well as paying for their expenses. To prepare for the event, which had the peasants quite excited, the village committee organized an intensive two-day training program for the athletes. Both the athletes and those who cheered them on later commented that their participating in the Games was very valuable. In the words of Mrs. Liu:

The Peasants’ Games provided me with a unique opportunity to meet and get to know people from other villages. I have made three friends from other villages during the Games. Although now we could not meet each other frequently, we still keep in touch though telephone and sometimes exchange useful information such as agricultural knowledge.

From the above, it is noteworthy that four out of the eight public spaces in H village have been built or organized by the government, including daily life public spaces (the washing spots), recreational public spaces (the village square and teahouse), and event-based public spaces (the peasants’ games). It is interesting to note that religious public space is the only type of public space not prompted by the government, and villagers have to arrange public spaces by themselves for religious practice. In addition, none of village leaders go to religious public spaces since it is a widely known principle that members of the communist party of China are not allowed to have any religion, let alone participate in religious activities.

It is also evident that the government built these public spaces in 2005 and 2006, which is due to the policy of “new socialist countryside construction” launched in 2005, since one of this policy’s measures is to provide funds to increase construction of infrastructure and public services in rural areas. In H village, the village committee is comprised of five members (i.e. village leaders), four males and one female, who not only engage in the planning of these public spaces and having them built, but also visit these public spaces from time to time like ordinary residents. It is rare to find rural women develop strong relations with the village leaders through public spaces. While on the one hand, as noted, women are not used to being active and open in the presence of men, and since village leaders are commonly male, rural women are normally quiet and have little interaction with village leaders when they visit public spaces. On the other hand, many rural residents still regard the government (i.e. village leaders) as their parents (fumu guan) and as they have never considered themselves to be on an equal basis with the village leaders (Li & Wu, 1999, p. 165), rural residents, especially village women, would not presume to include village leaders in their friendship network.

Mutual Aid as a Result of the Enhancement of Social Networks through Public Spaces

Public spaces provide a platform and opportunity for women in rural Chinese villages to maintain, enhance and expand their social networks. Although these new or strengthened social ties positively influence their daily lives, the contribution of expanded social networks is most obvious in times of need. As Cattell, Dines, Gesler and Curtis (2008) have pointed out, public spaces bring people together; they are places where not only friendships but also support networks are created. My observations, focus groups and interviews reveal that new relationships forged in public spaces foster physical or emotional support and co-operation. In short, enhanced social networks allow for greater levels of mutual aid among the village women. Three important dimensions along which this support takes place were identified: “mutual aid during illness”, “mutual aid during house construction”, and “mutual aid during the agricultural busy season.”

Mutual Aid during Illness

In general, Chinese hospitals offer limited healthcare to patients; for example, there is no catering service in most hospitals. Thus, it is rare to find a patient staying in the hospital alone, since family or relatives are normally present to look after the patient by serving meals and assisting with the treatment when necessary. Due to the high cost of hospitals, most villagers choose to return home for recuperation after staying in the hospital only for a short period. In rural communities, when a peasant becomes ill, friends will visit or even offer to take care of the patient at the hospital or at home. Although they do not customarily bring any gifts, the emotional and physical assistance alone can make the patient feel better. As observed by Stafford, De Silva, Stansfeld and Marmot (2008), contact with friends is universally important for people’s health, especially for those living in deprived households.

During my fieldwork, I often came across groups of friends that knew each other through public spaces who were on their way to visit or look after a hospital patient. Friends that knew each other from religious and daily life public spaces were most likely to do so. Friendships formed in recreational and event-based public spaces were less likely to lead to any visiting of patients. Based on the characteristics of the different types of public spaces, the level of mutual aid during illness seems closely related to the location of actors as well as the interaction frequency. In the case of the church, the temple, the washing spots and the grocery shops, actors are likely to be from the same village or even neighborhood and thus it is convenient for them to visit ill friends. They are also likely to meet more frequently and thus have stronger friendships. On the other hand, friends who know each other only from weddings or the Peasants’ Games meet only occasionally and are generally acquaintances. Further, they are more likely to come from outside the village, so it would cost significantly more time and money to visit an ill friend. The following story of Mrs. Deng vividly shows how social networks formed in public spaces can assist rural women in times of illness:

Mrs. Deng (62 years old): In June 2005, Deng fell down when she was walking in the forest, resulting in severe fractures in her right hand. Her husband had been suffering from kidney stones for several years now, and he could not perform any heavy manual labor. Her son and daughter could not help either as they were working in Shanghai more than 650 km away. Ergo, the unfortunate situation was that there was no one to take care of Deng and her husband. To make matters worse, Deng injured herself during the rice harvest season, which was a source of great stress and worrying.

Deng is a Buddhist and she went to temple regularly. However, after her accident, she could not visit the temple. When other Buddhists realized that Deng had not gone to the temple for a long time, two of them went to Deng’s house to investigate the reason why this was so. Once they were aware of the situation of Deng and her family, six Buddhists went to Deng’s house the next day. These six Buddhists were good friends of Deng, who had met each other in the temple. They spent one whole day in Deng’s field to help her with the rice paddy harvest. After a busy day, they finished all the harvest work. Deng later said that if no one came to help her, she had planned to hire workers to harvest the paddy, since her son and daughter could not take a few days off from work without the risk of being fired. If she would have hired workers, these would have cost 30 yuan per day (at the time, 6.8 yuan=1 US dollar) in H village. So it would have cost her 180 yuan to hire the workers, which is no small sum for her.

Additionally, friends who Deng had met by doing the laundry at the washing spot helped Deng wash her clothes, which was a lot of work during the summertime as Deng did not own an air-conditioner or even a fan to keep the house cool. They took turns washing Deng’s and her husband’s clothes for more than two months while Deng recovered from her injuries. Deng said she greatly appreciated the help from these friendships, which would not have been possible without the temple and the washing spot.

Mutual Aid during House Construction

As living standards improve due to the remittances sent by migrants, some peasants who live in grass- or tile-roofed houses decide to build a two- or three-story brick and cement house on a foundation. In rural areas, house construction is an important occasion and has the same impact as a wedding. Friendships established in public spaces could result in peasants helping each other with house construction in different ways. For one, friends might help each other through manual labor, engaging in the actual construction of the house. Alternatively, they may offer a loan with which to help finance the building project.

Among the women I interviewed, few friends are able to give manual labor assistance, as they are mostly middle-aged or elderly. As mentioned earlier, the village is situated in a mountainous area and the infrastructure is poor; there is not enough of a road for a car to reach a peasant’s house. Villagers would have to carry heavy bags of cement and lime uphill and on foot, not a task most of these women could physically do even if they wanted to. While peasants often hope to hire a carpenter or craftsperson who has experience with building a house in rural areas, due to the low average income and savings, they cannot afford these extra expenditures. Luckily, while most friends may not be able to provide physical aid, they are very happy to lend small sums of money. Being poor peasants themselves, they will not be able to lend more than one or two hundred yuan, but drawing upon an entire social network over the time it takes to build a house, peasants are able to cover the costs of house construction. Interestingly enough, peasants do not ask for any written contract when they lend or borrow money, and as such, there is no specific date on which to repay the loan. Coleman (1990) states: “[T]rust is an action that involves a voluntary transfer of resources (physical, financial, intellectual, or temporal) from the truster to the trustee with no real commitment from the trustee.” In the case of house construction in H village, it is clear that the trust level between friends is quite high. The following experience by Mrs. Yang is one example of how friendships formed in public spaces may prove invaluable when facing problems during house construction:

Mrs. Yang (42 years old): In 2005, Yang built a new two-story house, approximately 250 square meters in total. However, when it was near the date of completion, she could not finish the house construction due to financial problems. Yang is a Christian and goes to church every Sunday. When the following Sunday she told the other church members about this problem, they asked her how much money she needed to borrow to finish the house and promised that they would come up with the needed funds. A few days later, several church members visited Yang’s house with 2,300 yuan, which had been collected from the local Christians, all of whom had lent 100 yuan each, except for one member who was relatively well off and lent 300 yuan, while two members that lived under the poverty line could not afford to lend any money. Yang was very grateful for these friends’ help, and promised that she would pay back the money as soon as possible, to which her friends replied that she should take her time and repay them whenever she could afford to. None of the friends asked for a contract from Yang.

Mutual Aid during the Agricultural Busy Season

In the village, peasants are busiest from June to August, when they have to do the most agricultural work. Due to the large number of men that have migrated to cities for work, there is a huge labor shortage in the village during the harvest. H village is dominated by the so-called “386199” group, which applies to women, children, and the elderly. The name of the group derives from the fact that March 8 is Women’s Day, June 1 is Children’s Day, and the ninth day of the ninth lunar month is “Respect the Elderly” Day in China) (Bai & Li, 2008, p. 97). Most members of the “386199” group are not well suited to engage in agricultural production. To finish the work in spite of this shortage, peasants will hire laborers to help them with the harvest, although this is costly.

During the interviews, female villagers were asked whether friends that they knew through public spaces would help each other during the harvest season. I found that only a minority help friends during the agricultural busy season. One reason for this is the short interval between the sowing and the harvest of a rice paddy; peasants must finish the work in just 20 days. As such, each household is generally too busy finishing its own work to have any time to help others. However, those who have fewer paddies to sow and harvest were willing to offer to help other people after they finished their own work.

As with mutual aid during illness, those that were able to help friends that they had met through public spaces during the busy season knew each other from the temple, the church, the washing spots, or grocery stores. They appear more inclined to help due to the high frequency of interaction in these public spaces. Since increased interactive activities promote stronger mutual feelings, friends from these public places will go further to provide mutual aid. In fact, it would seem that, at least in this particular rural Chinese community, friends that regularly meet in public spaces have relationships that have exceeded the level of “friend” and even in some cases, that of “kinship.” This closeness has a direct impact on the livelihood of women because such friendships can replace the function of kinship, which is missing due to outmigration during the harvest time. This kind of social network has thus played the role of social support for peasants, becoming a “functional alternative.” The case of Mrs. Zhang shows how social networks formed in public spaces can lead to offers of assistance and advice when she found herself is in need of a helping hand during harvest time.

Mrs. Zhang (26 years old): Zhang went to church every Sunday. During the agricultural busy season of 2006, Zhang had recently given birth to a baby with very poor health that required much care, and she had no time to harvest her rice paddy. With Zhang at home, her husband, suffering from a hand disability, is not able to do all the work. After finding out about their problem, some friends from church came to Zhang´s house to help them with the paddy harvest. They also gave the young couple some valuable suggestions on how to take care of the newborn baby. Zhang felt very grateful for her friends´ help and expressed that the church was not only a place to practice one’s beliefs but also building friendships. She felt that the latter was especially important for her since she came from outside the village and had few social networks in H village. She regarded these friends from the Sunday church meetings as her “family away from home,” with which she had close and intimate relationships.

Conclusion

In H village, public spaces not only meet the demand for suitable physical locations for religious activities, leisure, and domestic chores but also provide a platform for women to enhance and expand their social networks. Based on qualitative data collected through participant observation, focus groups, and interviews, this research has sought to explore the importance of public spaces in the development of rural women’s social networks and to highlight how these social networks foster the exchange of mutual aid during illness, house construction, and the agricultural busy season.

Because rural Chinese women’s social networks are restricted by traditional, patriarchal gender norms and poor geography and infrastructure, there is little chance for them to build new social contacts or even to maintain existing networks. This research shows public spaces can provide them such opportunities. In H village, there are eight kinds of public spaces, which are categorized into four types according to their main functions: daily life public spaces (washing spots and grocery stores), recreational public spaces (the square and teahouse), religious public spaces (the temple and the church), and event-based public spaces (sites for weddings and sporting events). Rural women make valuable social contacts and maintain existing networks through face-to-face interaction with other members in these public spaces. For example, women can meet other Buddhists during their regular worship at the local temple, and it is common to find they build new friendships there. In washing spots, women have close chats while doing the laundry, which strengthens their relationships.

Strong friendships and enhanced social networks formed in public spaces positively contribute to women’s daily lives, as well as in times of need, especially in the form of mutual assistance and co-operation when they need to borrow money for building a house, need help during illness, or need an extra hand to finish the harvest. I also found that while friendships established and maintained in religious public spaces are most likely to provide mutual aid in times of need, women who know each other from daily life and recreational public spaces could count on each other to a certain extent, and those who meet in event-based public space are least likely to help each other. I argue that these findings are due to the fact that women have more frequent, regular and closer interaction with each other in religious public spaces, which in turn promotes stronger mutual feelings and the desire to help. Therefore, the enhanced social networks that arise from these public spaces are more likely to translate into the provision of mutual aid, which can even replace the function of kinship to some extent, acting as a “functional alternative.” For instance, during the agricultural busy period, friends from public spaces can help left-behind women with the paddy harvest, substituting for this function of out-migrating men.

In brief, public spaces have a significant impact on rural women’s social networks, which in turn assist their life and works. Thus, it is important to promote public spaces in rural China. With the implementation of the new socialist countryside construction policy since 2005, the government of H village has built several public spaces to satisfy rural residents’ daily demands such as the need for washing spots and a village square. It is interesting to note that religious public spaces are the only type of public space not supported by the government although this research finds it plays an essential role in believers’ religious practice and friends from the church or the temple are more likely to help each other than any other type of public space.

Notes

References

-

Abaza, M., (2001), hopping malls, consumer culture and the reshaping of public

space in Egypt, Theory Culture Society, 18(5), p97-122.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/02632760122051986]

-

Amin, A., (2008), Collective culture and urban public space, City, 12(1), p5-24.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/13604810801933495]

-

Bai, N., & Li, J., (2008), Migrant workers in China: A general survey, Social Science

in China, XXIX(3), p85-103.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/02529200802288369]

- Cao, H., (2005), Public space and order reconstruction in rural community, Tianjin Social Science, 6, p61-65.

-

Cattell, V., Dines, N., Gesler, W., & Curtis, S., (2008), Mingling, observing, and

lingering: Everyday public spaces and their implications for well-being and social

relations, Health & Place, 92, p179-200.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.10.007]

- Coleman, J., (1990), Foundations of social theory, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Department for Transport, Local Government and the Regions (DTLR), (2002), Green spaces, better places: Summary of the final report of the urban green spaces taskforce, DTLR, London.

- Fei, X. T., (1992), From the soil: the foundations of chinese society, University of California Press, Berkeley, CA.

- Habermas, J., (1991), The structural transformation of the public sphere, The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Hartley, J., (1992), The politics of pictures: The creation of the public in the age of popular media, Routledge, London.

-

Howell, P., (1993), Public space and the public sphere: Political theory and the

historical geography of the modernity, Environment and Planning D: Society and

Space, 11(3), p303-322.

[https://doi.org/10.1068/d110303]

- Irazabal, C., (2008), Ordinary place/extraordinary events: Democracy citizenship, and public space in Latin America, Routledge, New York.

- Jaschok, M., & Shui, J., (2011), Women, Religion, and Space in China: Islamic Mosques & Daoist Temples, Catholic Convents & Chinese Virgins, Routledege, New York.

- Kohn, M., (2004), Brave new neighborhoods: The privatization of public space, Routledege, New York.

- Krueger, R. A., & Casey, M. A., (2000), Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research, Sage, Newbury Park, CA.

- Li, B., & Wu, Y., (1999), The concept of citizenship in the People’s Republic of China. In A. Davidson & K. Weekley (Eds.), Globalization and citizenship in the Asia-Pacif, Macmillan Press, London, p157-168.

- Li, S., (2010), The Online Public Space and Popular Ethos in China, Media Culture Society, 32(1), p63-83.

- Lindlof, T. R., & Taylor, B. C., (2002), Qualitative communication research methods, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

-

Liu, J., (2000), Classical liberalism catches on in China, Journal of Democracy, 11(3), p48-57.

[https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2000.0059]

- Low, S., & Smith, N., (2006), The politics of public space, Routledge, New York.

-

Low, S., (1997), Urban public spaces as representations of culture: The plaza in

Costa Rica, Environment and Behavior, 29(1), p3-33.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/001391659702900101]

- Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B., Designing qualitative research, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, (2006).

- Mcbride, K., (2005), Book review of brave new neighborhoods: The privatization of public space, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 29(4), p997-1009.

-

Melucci, A., & Avritzer, L., (2000), Complexity, cultural pluralism and democracy:

Collective action in the public space, Social Science Information, 29(4), p997-1009.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/053901800039004001]

- Rowe, W. T., (1990), The public sphere in modern China, Modern China, 16(3), p309-329.

- Shi, T., (1997), Political participation in Beijing, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Sorkin, M., (1992), Variation on a theme park: The new American city and the end of public space, Hill and Wang, New York.

-

Staeheli, L. A., & Mitchell, D., (2006), USA’s destiny? Regulating space and creating

community in American shopping malls, Urban Studies, 43, p977-992.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980600676493]

-

Staeheli, L. A., & Mitchell, D., Locating the public in research and practice, Progress in Human Geography, (2007), 31, p792-811.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132507083509]

-

Stafford, M., De Silva, M. J., Stansfeld, S. A., & Marmot, M. L., (2008), Neighbourhood social capital and mental health: Testing the link in a general

population sample, Health & Place, 14, p394-405.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.08.006]

- Wang, D., (1998), Street culture: Public space and urban commoners in late-Qing Chengdu, Modern China, 24(1), p34-72.

- Wang, W., (2005), The means analysis on the management of public space, Statistics Research, 2, p64-66.

- Wu, Y., (2002), Public space, Zhejiang Academic Journal, 2, p93-94.

-

Zhang, J., Conwell, Y., Zhou, L., & Jiang, C., (2004), Culture, risk factors and suicide

in rural China: A psychological autopsy case control study, Acta

Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 110(6), p430-437.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00388.x]

-

Zheng, Y., & Wu, G., (2005), Information technology, public space, and collective

action in China, Comparative Political Studies, 38(5), p507-536.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414004273505]

- Zheng, Y., (2007), Technological Empowerment: The Internet, State, and Society in China, Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA.

- Zhou, S., (2003), Rural Public Space and Culture Construction, Hebei Academic Journal, 2, p72-78.