Analysis of Changes in Female Education in Korea from an Education - Labor Market Perspective

The purpose of this study is to analyze the changes in female education and how these changes have affected the labor market, during the period from Korean Independence until the present day. In order to achieve this purpose, concepts such as the awareness level of female education, present conditions of participation of educated women in the labor market and the changes to these factors were examined for gender equity. This paper achieves this goal by examining literature review, including research done on previous female education, participation of females in the labor market, and the patriarchal structure of Korean society. The results of this analysis show that although there has been rapid growth in the quantitative measures of female education in Korea, there is a significant discrepancy between the level of female education and participation in the labor market. Therefore, the differences in the field of education between genders or among female groups should establish self-identity, by establishing an educational terrain where female value is not recognized as factor of diversity, and operating as a driving force for social change. For instance, female education in Korea has come to a point where it needs various educational policies that go beyond mere quantitative expansion and address the issues of qualitative education, the transition from education to the labor market, and take into consideration differences within the female group. This would firmly establish women, not merely as the subject of compensation due to discrimination, but as one of the primary foci of education

Keywords:

Female education, education-labor market, gender equality, gender perspectiveIntroduction

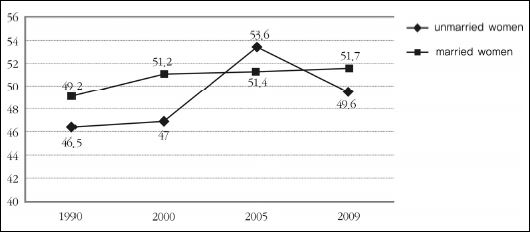

Educational opportunities for females have expanded rapidly since provisions for girls’ education were included in the Korean Constitution in 1948. According to the Gender Statistics in Korea, in 2009, 98 percent of girls were enrolled in elementary school, 96 percent in middle school, and 92.9 percent in high school. In higher education, 68.1 percent of girls were also enrolled, with 82.4 percent of young women in secondary education continuing on to university (Ju, 2010, pp. 187-192), demonstrating how higher education has become the norm. This is astonishing if you consider that in 1952, when female education was first guaranteed by law, enrollment of girls in any form of education was only 36.3 percent. This statistic perpetuates the conventional view that gender inequality no longer exists. However, examining this from the perspective of labor force entry, we can see that gender inequality does persist. For example, in 2009, female participation in the economy was just 49.2 percent compared to 73.1 percent for men - 23.9 percent difference. Of the 62.4 percent of women holding university degrees or higher entering the labor force, 52 percent are married. Given that 80.8 percent of women with university degrees in the labor force are unmarried, we can infer that it is difficult for women to maintain jobs once they get married and have children. Women in higher positions, such as council women, senior staff, managers and professionals, make up just 20.6 percent of women in the labor force (Ju, 2010). This shows that there remains an important difference between the rate of increase in the level of education and corresponding improvements in women’s entry into the labor market and career promotion. With improved quality of education, Korean women are increasingly looking to find jobs. However, a patriarchal ideology and the influence of Confucianism still persists, pushing women into taking primary responsibility for child rearing and domestic housework, consequently making it harder for them to find jobs. Therefore, when discussing changes in female education in Korea, it is important to take into consideration the socio-economic context.

Previous researches related to changes in female education (Kim, Yang, Huh, & Yoo, 2001; Jang, 2003) have investigated the degree of gender perspectives imprinted in education throughout history. Kim, Yang, Huh and Yoo (2001) classified how females were treated by the education policy across several periods. Jang (2003) analyzed educational policy from Korean Independence until the early 2000’s from the standpoint of gender issues, and categorized this into four periods: preparatory, introduction, establishment, and development. Their researches point out that the quantitative increase in educational opportunities for females have not resulted in gender equality in education. They have also postulated that if education policy is not coupled with a policy of gender equity, improvement in the quality of female education may in fact deepen gender inequality. However, they have overlooked the fact that entering the labor force is limited by gender and not by level of education, and thus, have not examined the complexities of how socio- economics is changing female education.

This paper focuses on these issues and aims to objectively examine the current role of female education in Korea, not only from within the confines of education but also from the perspective of supply and demand of female labor. The primary reason for examining the changes in female education from a labor market perspective is to bring to light gender inequality issues that are hidden within the quantitative increase in educational opportunities for females. Despite impressive increases in educational opportunities for women, if schools are imparting knowledge and skills depending on gender, and if this stratifies jobs and, in turn, limits women’s potential, then there is a significant difference in education depending on gender. Educational policy in Korea has been malleable and highly dependent on politics. In addition to this, views on female education are linked to patriarchic ideology stemming from deep-rooted Confucian tradition. Thus, simply examining this issue from an educational perspective limits the value of the analysis. Therefore, this paper aims to analyze the complex changes in female education within the context of both education and the labor market.

In order to accomplish this research, this paper was prepared by means of literary research. Various works were analyzed, including previous research related to female education, participation of females in the labor market, and the patriarchal structure of Korean society. Diverse governmental statistics were also analyzed. Based on the above-mentioned research material, chronological changes in the landscape with regard to gender, education, and labor were analyzed as well. The scope of analysis for this research is the changes in female education from Korean Independence, when females first started to receive education institutionally under law, until present day. This paper also gives a very narrow definition to female education as education given to females, as well as in the broader sense of education opportunities for females - and all educational activities that influence educational content, including educational policy. This does not merely serve the purpose for identifying females as recipients of education but to firmly establish women as equal to men the primary focus of the education field.

Theoretical Background

Female Education and Gender-specific Division of Labor

The format and content of female education is closely related to women’s responsibilities at home and in society. Therefore, in order to analyze changes in female education, it is necessary to analyze the role of educational institutions in the division of labor in a capitalistic system. One framework that imparts such insight is socialist feminism. Socialist feminism analyzes the gender-specific division of labor from two different dimensions. The first dimension is the public-private sector. Men participate in wage generating labor, while women participate in wage-less production in the form of domestic labor. The second dimension is horizontal and vertical gender differentiation. The labor market does not recognize female labor to have the same value as male labor, limiting women to clerical work, jobs in the service industry and other specific areas. The divisions of labor by gender in the first and second dimensions interact together. Regarding women as wage-less domestic laborers is to regard their primary responsibilities to be domestic work and childcare, and working in the labor market is merely seen as secondary work (Ravetz, 1987).

Furthermore, socialist feminism asserts that women are suppressed in a similar fashion due to the aforementioned problems and thereby face inequality. However, they argue that the female experience varies by social factors such as class, race, and region. The gender division of labor depends on female students’ class and region, and the students are more or less accepting of these differences based on their socio-cultural context (Ramazanoglu, 1989). The differences within female groups can be seen through research examining female labor. Although it is true that the labor market has an inequitable gender division of labor in Korea, it is also clear that there are additional differences between women that, have always existed. In comparison to men, women generally share more common experiences with their families and relatives, even though this situation manifests in various ways within the female group.

Therefore, analysis that simply contrasts female education with male education is limiting. It is difficult to say that all women have received the same level of education in the Korean society, as women have existed in different positions within the capitalistic production mechanisms. Even during the period when the majority of women only received primary schooling, there were some who did receive secondary education. Likewise, when some women received vocational training, others received professional education in areas often regarded to be strictly in the male domain such as the natural sciences and engineering. From this perspective, Arnot’s research (1982) is extremely significant. Arnot took an interest in the responsibilities women undertake in the public and private spheres. Arnot noted that the experiences of women based on class, as well as sexual oppression through school education were re-created. Moreover, within the school system, sexuality in the working class and middle class were emphasized. This re-creation was not considered mere differences between the genders, but also class differences within the female group, as in the working class versus the bourgeois.

In conclusion, to understand changes in female education, it is important to give attention to differences within the female group, in addition to the overall gender division of labor in the labor market. The domain of production and reproduction is gender-differentiated by class. Therefore, changes in female education in Korea must be analyzed in the contradictory context that women are straddling both the public and private spheres.

Changes in Labor, Education, and Gender

Changes in labor, education, and gender are influenced by changes of the industrial structure, the socio-cultural characteristics, and the education level of women. First of all, the demand for female labor and changes in the labor market are dependent on industrial changes. In the early stages of the industrial era, the manufacturing-centric plant industry structure dictated that the majority of working class women were utilized for manual labor. Therefore, working class females could play a dual role in both the production and reproduction cycles. Simultaneously, a negative outlook on women in the labor market was propagated in order to maintain a patriarchal hierarchy and the traditional division of labor by gender, with the man taking the position of the primary bread-earner and the female taking charge of domestic reproduction responsibilities (Lee & Chung, 1999, pp. 91-93). Therefore, during the early industrial era, women who entered the labor market were regarded as threatening the jobs and wages of their male counterparts and as having failed to properly look after their household matters - which starkly contrasted with the image of middle and upper class, full-time housewives.

Subsequently, the Family Wage System was the main system among the various measures taken to ensure that middle and upper class women stayed home. Sufficient wages were given to male labor workers with family allowances in order to prevent the entry of other family members into the labor market. With a labor market that is based on a Family Wage System, women’s education is regarded a waste rather than an investment; it was recognized that their education only needed to be sufficient enough in order to be responsible for reproduction, and it is taken for granted that women would work for lower salaries in lower positions as they are not the primary source of a family’s income. Therefore, females with higher education and above either fully occupy themselves in reproduction and consumption, or in the case of working, it is only feasible to work while they are not married. On the contrary, in a society based on knowledge and information, the ability to learn and apply information is different among female groups. Women with degree are easy to access information and knowledge and have actively entered into the labor market. Family-friendly corporate culture and government policies support the creation of positive “work-life balance” so that educated females may continue with their economic activities even after having children. However, even in a society based on knowledge and information, lower class females without easy access to information are still readily exposed to a labor market, that is not equivalent to that of their male counterparts. On the other hand, the phases of women’s education also vary by their awareness level. Women are equipped with the insight to be critical of their social structure through education. This denotes that women are not primarily shaped by the social structure and cultural habits, but that they actively and freely contribute to influencing the social system.

The three pillars of labor, education, and gender and their changes are influenced not only by the economic context but also by the cultural customs of the society. On the surface, the economic activities of women are deeply engrained in and influenced by a more socio-cultural context such as social norms or traditions.

With this in mind, this study has considered the awareness level of female education, present conditions of participation of educated women in the labor market and the changes to these factors over time. For each era, an analysis will be performed on the gaps between women’s level of education and their participation in the labor market, as well as approaches being taken to close the gaps. The placement of gender equality will need to be considered in aggregate with regard to aspects such as the accessibility of education opportunities, education culture and message conveyed at schools, either formally or informally, and whether educated women are valued equally with their male counterparts. The degree of participation of women in economic activities may be regarded differently dependent on whether female education is viewed as a waste or an investment. If women’s education is perceived as a luxury, entry of educated women into the labor market will be low. Nor can the progress of female education level be linked to upward social mobility for women. Moreover, aspects of female education will differ depending on whether females are considered as a single gender categorization or whether the differences within various female groups are considered separately. As such, each aspect will clearly manifest within each era although contradictory traits will be seen at the same time; thus, there will be inter-dependence among these aspects and such traits will also affect each other. Therefore, we show that the changing process of women’s education will unavoidably have complex characteristics.

Changes in Female Education in Korea

Absence of Gaps between Education and the Labor Market: the 1950s

After the Korean Independence, when democracy was adopted as the educational ideology, equal education opportunities between men and women were guaranteed. Three years later, when the United States military occupied the area south of the 38th parallel, educational discrimination against women was abolished and a co-educational system was adopted to complement the limitations of female education. Female education was institutionally and judicially endorsed on July 17, 1948 when it was declared as part of the Korean Constitution. Article 31 of the constitution specifies that “every man and woman must be given equal education opportunity”. Enacted on December 31, 1949, the education law stipulated that primary education was mandatory for all citizens; following the enactment, mandatory education was implemented on a large scale in 1950. Just after Korean Independence, the average level of education among females was lower than that of males; as a result, the level of educational progress was higher among females. In 1947, among the female population, 11 percent were primary school graduates, 1.9 percent middle school graduates, and a mere 0.1 percent were graduates from college and above (Kim et al., 2001, p. 202). About forty one percent students enrolled in primary schools were female in 1954 and 43.6 percent in 1958 - this accounted for an approximate 2 percent increase. Increases were even more prominent at the higher levels of education such as middle school and high school.

In the 1950s women’s education was based on mere formalities of equality. Instead of as a norm for humanitarian subjugation, the ideal female figure (a wise mother and kind wife) was emphasized as a result of post war gender-specific labor division. Prescribed to be a potential housewife and ideal female figure, a female student was given the responsibility to be an assistant to a housewife (Kim, 2008). The ideal female figure ideology was promoted to the female students. School education was an extension of practicing to become a housewife, thereby serving the husband, educating the children, and taking charge of domestic affairs. The role of a housewife was explained to be someone that creates harmony amongst family members and makes the home a place for a community of love and warmth.

While the primary purpose of women’s education was established to foster an ideal female figure, job differentiation specifically for females also started to take place, as female participation in the agriculture and manufacturing industries was encouraged. The social realities of that time, such as the recruiting of men due to the war and post-war recovery activities and the prevalence of unemployment, also contributed to this trend. The Korean economy was struggling in the 1950s. In order to recover from the ruins of the Korean War, light industries based on cheap labor were solidified. The most rapidly growing industries in the 1950s in domestic Korea included milling, textile and sugar manufacturing – all of which were based on the processing of overseas aid goods such as flour, raw cotton and sugar. Therefore, a minority of primary school graduates worked until marriage under the low wage system within the manufacturing industry. Women entered the labor market in increasing numbers with the advent of the manufacturing industries in the fifties. However, the Korean economy was still largely sustained by the agricultural industry; thus, approximately 85 percent of the entire female population participated in agriculture – although primary schooling was specified as an obligation, many absences were noted at the schools due to the shortage of labor in the rural communities.

Having examined the characteristics of women’s education in the 1950s, there was an absence of educational policy that recognized gender differences because survival itself was more important than gender equality in 1950s. Gaps between academic achievement and entry into the labor market simply did not exist. As democracy became institutionalized after Korean Independence in 1945, efforts were put in place to reduce gender discrimination from education. However, a gender- specific division of labor occurred nonetheless, as the primary domain for women was in the home, and such separation of duties was widely accepted as logical. In 1949, even as many females were being given opportunities to lawfully receive education due to compulsory primary education, the necessity for education among women still remained low. With the exception of the few privileged, sending daughters to school was considered a luxury. At that time, the socio-cultural and economic conditions of Korean society were too deficient for women’s education to be considered an investment.

Occurrence of Gaps between Education and Conditions of the Labor Market: Between 1960s and 1970s

Tendencies to recognize female education as a luxury persisted until the 1970s. However, educational opportunities were broadened to accommodate secondary schooling. In 1966, the ratio of males lacking primary school degrees was 41.1 percent and that of females, 22.4 percent. The removal of middle school entrance exams in 1969 and standardization of the secondary school system played an influential role in boosting the education levels amongst males. In addition, it contributed to the creation of opportunities for females to receive middle school education, to a certain degree. Prior to the removal of middle school entrance examinations in 1965, the ratio of males admitted to middle schools was 59.9 percent. The ratio of female entry into middle schools was 47 percent. However, with the removal of entrance examinations, a remarkable increase in the admissions occurred.

In September 1961, the Temporary Special Cases Act for Education exasperated the situation for female entry into the higher education system. Between 1962 and 1963, the National Eligibility Examination System for College and University Admissions (1962-1963) determined passing rates separately for male and female students. However, this policy was hindered when an enforcement decree on the fixed number of post secondary students was passed in 1965 (Kim et al., 2001, p. 254). In 1961, normal schools with a focus on cultivating primary school teachers were changed into two-year junior teacher’s colleges; this change helped to broaden, to a certain extent, the level of higher education for females (Jang, 2003). In 1976, the Basic Act for Vocational Training was amended to create opportunities for select females to receive vocational training, and the two-year, female-only vocational training centers were founded.

From an educational content standpoint, female education was focused on male-cognizant feminization education; however, around 1975, women’s humanitarian rights were called into attention, forming the notion that physiological differences between males and females should not manifest into social discrimination. Moreover, the seventies saw the beginnings of a shift in the public perception of women, where society began to feel that women should also be raised to be competent and pursue careers. The opening of a women’s research laboratory at Sookmyung Women’s University in 1976, and the creation of a women’s studies course at Ewha Womans University in 1977 are examples of this change in perception.

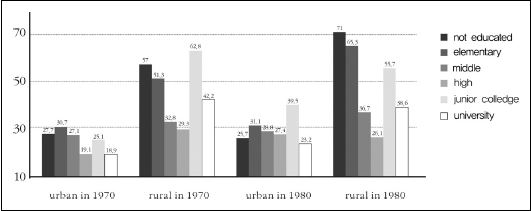

During the rapid industrialization in the sixties, there was a prominent advancement of women’s participation in the non-agriculture wage labor market. In particular, participation among women increased rapidly in the manufacturing sector. With the introduction of the First Master Plan for Economic Development (1962-1966), government-led industrialization efforts were intensified through the early 1980s. During this period, women were generally expected to fulfill duties of an idealized female figure (the wise mother and kind wife). Those who received high school education were expected to work as manual workers for low wages and bore the stigma of an ‘Industrial Laborer’. During the implementation of the economic development plan, female laborers outnumbered male laborers not only in industries concentrated by heavy labor, but also in export-driven businesses. As demonstrated in <Table 4>, the number of females occupying jobs in the agriculture and fishing industries remained high. However, their presence gradually declined, and the ratio of females as production workers increased. A study in 1977 showed that 66 percent of female plant workers were between the ages of 17 to 21. Of female workers, 95 percent were found to be under the age of 25, and 98 percent of them were single. Among them, 88 percent of the plant workers had less than middle school education (Koo, 1987, pp. 103-112).

On one hand, even though demand for female workers increased with industrialization, women with higher education were not encouraged to enter the labor market (Lee, 1996, p. 124). Female graduates of Junior Colleges were able to participate in the labor market as teachers, nurses, and administrative workers, but the job market remained small, and women found it difficult to continue with their careers after marriage due to enforcement of employment termination at marriage, which persisted through the 1980s. The employer would receive a signed memorandum that the female would resign upon marrying. A custom for imposing resignation upon women after marriage was prevalent in the labor market. Women’s policies were designed and enacted as a sub-policy to other policies. Women were not regarded as autonomous and active targets for policy enforcement, but were regarded as objects of mobilization for economic development under low wage. Therefore, there was not a favorable perception of young female workers.

Finally, the fact that women’s potential in the labor market was not fully realized nor developed due to the prejudices and stereotypes of women’s roles and government-led economic development until the 1960-1970’s speaks to the gaps that emerged between the education received by females and the realities of the labor market. There were no known policies with regard to female education; yet, educational opportunities broadened with the removal of entrance exams from primary to secondary education (middle school). However, a considerable number of female workers worked under a low wage labor system while missing opportunities to receive further education, and the few instances where women did receive higher education, they rarely worked in the labor market after graduating. Unlike middle class females that attended institutionalized schools, lower class females who attended factories were subject to scorn and mockery due to the prejudices and stereotypes of women’s roles.

A Personal Approach to Gaps between Education and the Labor Market: From the 1980s until the mid-1990s

Since the 1980’s, when the low proportion of educated women being utilized in the labor market became a social issue, female education began to be formally discussed as part of educational policy. However, the resolution of this issue was viewed as a personal issue. Between the 1980s and the mid 1990s, female participation in middle and high school was nearly universal. In the early 1980s, with the implementation of a quota system for the number of graduate, the number of graduates increased rapidly. By 1995, 49.8 percent of females among the total graduate of high schools were granted admission to higher education.

As such, as the education level among females increased, the level of awareness also increased, and the issues of gender inequality in the education field gradually started to be discussed. When the Korean Women’s Development Institute (KWDI) was founded in 1983, equal opportunities were discussed and studies on educational equality took place – but this was merely a formality. Analysis of the classroom and textbook content of secondary education courses (middle and high school) show that an emphasis on creativity and activity was found for boys, while purity, patience, and attendance were the areas emphasized for girls - the school system had reproduced the values found in traditional, patriarchal society.

From the end of the 1980s, the education policy was drafted to include female education. At the 6th 5-Year Plan for Economic and Social Development (1987-1991), for the first time, female education policies were established as part of the national plan. The plan specifically included the elimination of gender inequalities in the education process, a reinforcement of vocational training for female students, and the broadening of opportunities for social education (Jang, 2003; Kim et al., 2001; Min, 2002; Chung & Choi, 2002). Moreover, in 1985, the Reform Measures for Gender Discrimination and its details were adopted in order to improve anti-discrimination practices in the field of education. With the start of the 6th Republic in 1988, the Office of the Parliamentary Minister was founded to focus on women’s issues, and with the newly established Office for Women’s Education Policy within the Ministry of Education, women’s education became an aspect of national affairs. At the 7th 5-Year Plan for Economic and Social Development (1992-1996), plans were put in place to encourage females to advance into the science and technology sectors, to enter in the school system administration and education profession, and to reinforce sex education in all phases of schooling for both males and females. With the rise of the Civilian Government in 1993, the committee for Education Reform, which ran from 1994 to 1997, devised an education reform program for the establishment of a new education system. With four revisions in its document, the women’s education policy was endowed with lower-level goals to promote ‘support for female vocation training opportunities’ based on a larger policy theme which to “implement a women’s education policy based on continued profession education.”

The specifics of policy changes can be listed as follows: provide support for the liaison between vocation training centers - in order to broaden vocation training at girls’ high schools - and between polytechnic colleges, junior colleges, open universities, broadcasting colleges, and academies of continued education where various vocational education opportunities for housewives could be set up and supported (Chung & Choi, 2002, pp. 327-331). However, such diverse education policies posed some problems in that they were not directly linked to education development but were separately developed; and as a result, with difficulties in obtaining active buy-in, the efforts were nominal. Moreover, the approach taken by such education policies was merely to insert education for females upon need, which produced limited results. Transitioning educational achievements to the labor market proved to be difficult.

As the proportion of the female population achieving higher education rapidly increased due to an accelerated expansion of higher education beginning in the early 1980s, women’s aspirations to enter the job market also increased; yet, there were not enough white collar jobs to accommodate the sudden rise of female graduates (Lee & Chung, 1999, pp. 81-83). From the beginning of the 1980s until 1990, female participation in the economic labor market expanded from 29.8 percent to a staggering 53.1 percent. This figure remains quite low when compared to the 93.9 percent rate for men. Therefore, even with industrial changes, the participation of highly educated females in the labor market remained relatively low compared to their male counterparts. Consequently, the economic benefits of education were considered low during this era, as higher education was considered a luxury - an education for the enjoyment of ascertaining new knowledge - and not a human resource investment.

Female education was included as part of the education policy for the first time between the 1980s and the 1990s. The education level of females increased and schooling at the middle school level was at full attendance with 50 percent of females being admitted into post-secondary institutions. However, the Ministry of Education’s creation of new educational policies were not based on the perspective of gender inequalities but rather as a change from a political standpoint; as a result, there was a substantial lack in the driving force for the implementation of female education policies. The labor market continued its conventions of gender discrimination in employment practices. Thus, a smooth transition of education achievements to the labor market remained difficult.

A Policy Approach to the Gaps between Education and the Labor Market: Post-1998

Beginning in the late 1990s, the debate over gender equality in education was absorbed into the discussion about human resources policy to encourage national economic growth. Training and utilizing female workers became a focal interest in national policy. Therefore, gender differentiation and the underutilization of highly educated women became an issue, resulting in the start of serious efforts to rectify this problem. Educational opportunities after 1998 show very little difference between the genders from a quantitative perspective. As shown in <Table 7>, female enrollment in middle and high schools is nearly universal, and university education has also entered the universal education stage.

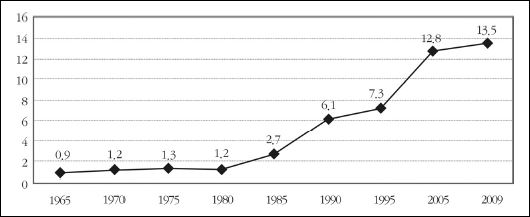

In 2000, the Korean government, in the name of utilizing highly educated women, tried to increase the number of female university students selecting natural sciences and engineering majors. As <Table 8> shows, female university students had been concentrated in the social sciences, humanities and the arts. In addition, the government passed ‘The Act on Fostering and Supporting Women Scientists and Technicians’ in 2001 in order to reduce the barriers between education and the labor market. This legislation was the basis of policies to encourage female students to pursue majors in the natural sciences and engineering, such as the development policies Women in Science and Technology (WISE), Women in Engineering (WIE), and The National Institute for Supporting Women in Science and Technology (NIS-WIST).

Female Student Rrate in Science and Technology*Source: Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2010)

Having displayed remarkable progress after the 1998 People’s Government, policies for mainstreaming gender issues were put into effect in order to examine what gender-specific effects would be induced if educational policy was established as a whole. In February 1998, the Office of the Parliamentary Minister (#2) was closed, and the Presidential Committee on Women’s Affairs was established. In January 2001, the Ministry of Gender Equality and the Office for Women’s Education Policy within the Ministry of Education were established. Furthermore, the 1st Master Plan for Women’s Policy (1998-2002) was initiated, a policy that included the expansion of female school principals, vice-principals and professors, the expansion of gender equality awareness amongst school teachers, and the strengthening of career guidance for female students pursuing diverse fields. Meanwhile, gender issues emerged in official government documents like the 5-Year Educational Development Plan of 1999.

In January 2000, an article on gender equality in education was appended to ‘The Fundamental Education Act’. The original Fundamental Education Act included the restriction of gender-specific educational opportunities, but this passive declaration was deemed insufficient to implement gender equality (Min, 2002, p. 90). Furthermore, due to raised awareness that the utilization of female labor was a direct advantage to the national economy, the fundamental direction of the Ministry of Education’s Women’s Education Policy was changed to the Development and Utilization of Female Human Resources, and the Expansion of Gender Equality Education Ideology. With the inception of the Participatory Government in 2003, the Ministry of Education was changed to Ministry of Education and Human Resources Development, and female development as a human resource was emphasized in the Office for Women’s Policy. Furthermore, the 2nd Master Plan for Women’s Policy (2003-2007) includes-provisions for developing women as a human resource by targeting career plans for female students, strengthening professional education through opportunities to pursue appropriate careers, fostering career awareness and job ethics, removing gender inequalities in textbooks, improving coeducation, expanding opportunities for female students in the natural sciences and engineering, and establishing development centers for women’s careers. It was a distinguishing mark where more diverse types of participation in the labor market were seen, although there was not a marked increase in female activity in the economy.

Economically Active Population by Sex and Educational Attainment in 1998, 2000, 2005, 2010Unit: In Percent

Moreover, the Asian financial crisis of 1997 led to the collapse of the single income patriarchic model and the introduction of the dual-income family model. Beginning in 2000, policies were introduced in an effort to further utilize the labor of married women. These policies included the Policy for the Creation of Jobs for Women, the Training and Support Program for Highly Educated Females, and the policy for ‘Creation of Family-Friendly Job Cultures’ to prevent discontinuation of careers due to childbirth and childrearing.

In a similar context, one of the noticeable characteristics of the post-1997 is that labor market participation had a dichotomizing effect among females. As a result of the labor market elasticity and the gender- specific division of labor, during the Asian financial crisis of 1997, many women were marginalized by first being fired from their full-time positions and later being rehired into temporary positions. As we can see in Figure 4, the number of temporary female workers rose from 39.5 percent in 2003 to 44.1 percent in 2009. On the other hand, 69.4 percent of newly created, high-income professional, technical and administrative jobs were filled by women, and the professional participation of women in the public sector is currently increasing. Examining changes the ratio of women by job type reveals that the ratio of women in professional jobs increased from 4.5 percent in 1998 to 19.9 percent in June 2010. However, there was a decline from 34.7 percent to 15.2 percent in the sales industry and a decline from 10.8 percent to 6.5 percent in the manufacturing industry (Korea National Statistical Office, 2010). In this manner, female participation in the labor market is being divided into temporary employee and permanent employee professions (Bae, 2009, pp. 66-67).

Discussion

The purpose of this study is to analyze the changes in female education within the relationship between education and labor market participation, from Korean Independence to the present day. In order to achieve this, we considered principal concepts such as the awareness level for women’s education, the conditions for participation of educated women in the labor market, and the types thereof. For each era, a comparative analysis was performed on the gaps between the proportion of educated women and their participation in the labor market and on the respective approaches taken to close the gaps. The particular reason to take the labor market context into account is to illustrate the gender inequalities that remain despite the quantitative expansion of educational opportunities for women.

The results of the analysis show that although there has been rapid growth in the level of female education in Korea, there remains a significant gap between the level of female education and their participation in the labor market. Legislative and policy frameworks for gender equality were created in the 1950s but fell into ruins following the Korean War, as female education was considered a waste, given the economic problems the country was facing. Women were expected to be satisfied with an elementary school education followed by joining the labor force, as seen in the low proportion (22.3%) females among middle school students in 1958.

With the removal of entrance examinations for middle schools in 1980, enrollment of women in middle schools rose to 92.5 percent. The number of women entering the labor market as unskilled and low-wage laborers increased likely because of the impact of economic planning and the subsequent rise of the export industry laborers in the 1960s and 1970s. Despite the significant number of women in the labor market, the dichotomy in public and private affairs meant that working women were not viewed favorably in society. Because of unfavorable circumstances of the labor market, women chose to remain home and faithfully assume their domestic responsibilities. Since the late 1980s, the difference in female education and participation in the labor market has been increasingly criticized by women, and government policy has been changed to include provisions for female education within educational policy. The government carried out policy revisions to counter discriminatory aspects of female education and to rectify unfavorable conditions in the labor market.

From 1998 through the present day, female education policies have been focused on differences within the female group, and on higher education for efficient human resource development, resulting in the diversification of academic majors, the fostering and utilization of highly skilled female workers, and other strategies. Moreover, although female education had previously been approached from the limited viewpoint of females as simply a recipient of education, now Korean government examines whether the effects of general education policy differ depending on gender. This had resulted in an expanded perspective on female education that includes both the effects and the results of policy. Looking from a labor market after 1998, with the expansion of opportunities in higher education for women, the numbers of women entering the labor market as professionals and administrators increased. Policies for a family-friendly job culture and the support of work-life balance have been enthusiastically pursued by major corporations and the public sector. Following the Asian financial crisis of 1997, the elasticity in the larger labor market and the disintegration of the single-income family model has resulted in an increased awareness of the necessity of women’s participation in the labor market. However, the majority of women are now entering the labor market as temporary workers. Occupational specialization within the labor market and gender-specific division of responsibilities within the family still persists. Under these circumstances, the majority of women in the temporary labor force are experiencing the double burden and conflicts of both employment and domestic duties.

Following these changes in female education in Korea, the main challenges are to both consider the similarities and differences within the female population, and to formulate a plan for the active transition from education to the labor market. The following discusses this more specifically:

First, there is a need for a universal female educational policy that exposes the differences among females. This policy needs to encompass feminine identity, and at the same time consider the differences in class, region and culture within the female population. Even though women have had the similar experiences in the contexts of Korean education and the labor market, it is more important to note that although the degree of differences within the female group is dependent on chronological periods, differences within the female group have always existed, and women have always had different educational opportunities and experiences.

Second, the transition from education to the labor market will be activated. If differentiation persists within the public and private spheres and within types of occupation and position based on gender, then education cannot avoid being influenced. Subsequently, there will be limitations on the effective transition from education to the labor market, in addition to restrictions in the continuity of the labor market. As we have seen before, entrance into the Korean labor market is severely limited for women, and women’s achievements in education are challenging to translate into favorable socio-economic positions. Therefore, a socio- economic framework must be developed to resolve the structure of the gender-specific division of labor, and education must be undertaken to encourage this change. Strategies for transition and sustaining the labor market must be specified according to school type and school level.

Third, education specialists have attempted to resolve the gender inequities in the education sector. Many gender equality policies have been implemented in the political context. Yet there remains a gap between education and policy and it is difficult to sustain the gender equality policies even though the political system has changed. Education specialists have a responsibility to propose a policy agenda of encouraging gender equality.

Finally, the paradigm for female education must transition from revealing inequality to establishing self-identity based on differences. Previously feminist education centered on school education such as problems in the educational process, textbooks or content, and school educational environment, from a feminist viewpoint. Such efforts led to achievements in offering females more educational opportunities, but such an approach compares females with males. This only serves to reveal gender inequality and the limitations in changing for the cooperation that will help the psychological and social growth of males and females (Kwak, 2008, pp. 73-74). Therefore, the differences between genders or among female groups within the educational field should establish self-identity, by means of creating an educational terrain where female value is not recognized as a factor for discrimination but simply as an element of diversity, and operate as a driving force for social change. For instance, female education in Korea has come to a point where it needs various educational policies that go beyond mere quantitative expansion and address the issues of qualitative education, transition from education to the labor market, and take into consideration the differences within the female group. This would firmly establish women, not merely as the subject of compensation due to discrimination, but as one of the primary foci of education.

References

- Arnot, M., (1982), ‘A crisis in patriarchy?: British feminist educational politics and state regulation of gender. In M. Arnot & K. Weiler (Eds.), Feminism and social justice in education, International perspectives, The Falmer Press, New York, p186-209.

- Bae, E. K., (2009), Economic crisis and Korean women: Women’s vision-of-life and intersection of class and gender, The Feminism Studies, 9(2), p39-82.

- Chung, H. S., & Choi, Y. S., (2002), Equality of educational policies in OECD countries, Korean Women’s Development Institute, Seoul.

- Jang, W. G., (2003), Development process of the Korean educational policies and its task from the gender perspective, Korean Journal of Educational Research, 41(4), p389-409.

- Ju, J. S., (2010), 2009 Korean gender perspective statistical handbook, The Korean Women Development Institute, Seoul.

- Kim, Kim,., (2008), A Characteristic of Hyeonmoyangcheo-Discourse for education of girl’s School in the 1950s, Journal of Korean Home Economics Education Association, 19(4), p137-151.

- Kim, J. I., Yang, A. K., Huh, H. R., & Yoo, H. O., (2001), The Women’s Education Transition Study of Korea, Korean Women’s Development Institute, Seoul.

- Koo, H., (1987), Women factory workers in Korea. In E. Y. Yu & E. H. Philips (Eds.), Korea Women in Transition: At Home and Abroad, Center for Korean-American and Korean Studies, Los Angeles, p103-112.

- Korea National Statistical Office, (1960), Economically Active Population Survey.

- Korea National Statistical Office, (1965), Economically Active Population Survey.

- Korea National Statistical Office, (1970), Economically Active Population Survey.

- Korea National Statistical Office, (1975), Economically Active Population Survey.

- Korea National Statistical Office, (1980), Economically Active Population Survey.

- Korea National Statistical Office, (1998), Economically Active Population Survey.

- Korea National Statistical Office, (2000), Economically Active Population Survey.

- Korea National Statistical Office, (2005), Economically Active Population Survey.

- Korea National Statistical Office, (2009), Economically Active Population Survey.

- Korea National Statistical Office, (1960), Economically Active Population Survey Retrieved October 1, 2010, from http://kostat.go.kr/portal/korea/kor_ki/1/1/index.action?bmode=read&cd=S002001.

- Kwak, S. K., (2008), The feminism education, Ewha Womans’ University Press, Seoul.

- Lee, M. J., (1996), Under-utilization of women’s education in Korean labor market: A marco-level explanation, The Journal of the Population Association of Korea, 19(2), p107-137.

- Lee, M. J., & Chung, J. S., (1999), Korean women’s education and participation into the labor market during 1980s and 1990s, Korean Social Science Review, 21(4), p75-114.

- Min, M. S., (2002), Reflection on Gender Issue in Educational Policy of Korea, Sociology of Education, 12(2), p81-97.

- Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, (2010), 2009 Report on the status of Women in Science and Technology, Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, Seoul.

- Park, Y. J., (1990), Women’s labor force participation in Korea, Trends in levels, patterns and differentials during 1960-1980. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania.

- Ramazanoglu, C., (1989), Feminism and the contradictions of oppression, Routledge, London.

- Ravetz, A., (1987), Housework and domestic technologies. In M. McNeil (Ed.), Gender and Expertise, Free Association Books, London, p198-208.

- Korean Educational Development Institute, (1965-2009), Statistical Yearbook of Education, Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, Seoul.