The Change of Women's Social Status in Korea

This paper examines changes in Korean women’s social status over the last 30 years, both before and after the enactment of the Women’s Development Act in 1995. Social status is a social form of differentiation and value assessment, and the status of men and women are positioned differently within its process. Thus, social status is not naturally granted, but it shows the vicissitudes of society. Women’s social status appears in the context of overall society, and this research examines the type variation of gender equality- as gender neutrality, gender recognition, and de-gendering or deconstructing the gender- as the status changes in politics, economy, human rights through statistics, and the status changes through laws and systems.

By tracing the improvement in Korean women’s social status over the last 30 years, I show that women’s social status has become practically equal to men’s in many social sectors, such as in occupation, legal rights, education, political participation, and other areas. However, despite all this evidence of official equality, there are still questions about the true improvement of women’s social status and gender equality due to remaining inequalities, such as the scarcity of women in professional fields, the prevalent imbalance in housework, and the increase of sexual and domestic violence towards women, the coherent belief in gender differences, and others. In the future, the endeavor for the improvement of women’s social status should explain the paradoxical inequality hidden underneath the superficial success that has been seen thus far.

Keywords:

Women’s social status, gender equality, gender neutrality, gender recognition, de-genderingIntroduction

Following the changes of the 20th century, the 21st century remains a century in which women’s social status is rapidly changing in Korean society. Since 1980, the feminist movement has brought gender inequality issues to the surface, and has begun a movement to demand the enactment of laws and systems for the improvement of women’s social status. During this time, the consciousness and the customs that discriminated women still existed in laws, systems, and various social sectors.

Therefore, more organized and far-reaching changes were necessary in order to improve the consciousness and the customs regarding sexual discrimination as well as the enactment and the reform of laws and systems to improve women’s roles and social status. During this time, the mobilization of women’s political participation and women’s rights and interest has visualized the endeavor to reflect women’s interest in politics.

Since then, the Women’s Development Act was enacted in December 1995 as a legal mechanism provided under the Constitution to stretch the principle of gender equality and to improve women’s social status across all social sectors. This law established an initial basic plan which is focused on 6 basic strategies and 20 political issues, such as the reform of laws, systems, and customs, a move towards more representation, and the promotion and stabilization of women’s employment. The law requires that the basic plans for women’s policy be re-established every 5 years (Special Committee on Gender Equality, 1998).

The efforts to improve women’s status throughout society since 1980 have resulted in the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1987, the Family Violence Prevention Act of 1997, the introduction of a 30% quota for the public nomination of women in 2000, and the abolition of the patriarchal family system in 2005. With these results, it is clear that Korean women’s social status has been improved in the last 30 years. This improvement has been focused on economic participation, education level, political participation, legal protection from violence against women, and other areas.

However, progress towards improving social status is being delayed due to the resistance of the privileged class in the patriarchal social or ders that still remain in Korean society. Women remain in a weaker position in the labor market; there is a scarcity of women in decision-making positions; and the violence against women continues to increase. Furthermore, married women are experiencing challenges in work-life balance as their housework remains in addition to their now heavy job tasks when there is limited gender division of domestic labor.

According to recent research conducted by the Korean Social Policy Institute in 2010 (Korean Social Policy Institute, 2010), childcare (57.1%), social prejudice and custom against women (26.2%), and unequal working conditions (15.4%) are considered the largest obstacles to the entry of women into the realm of public affairs. The improvement of disadvantageous laws and systems for women (41.7%), government reinforcement of women policy (23.6%), and the change of social consciousness for gender discrimination (19.7%) are considered to be the most powerful measures to improve women’s social status, rights, and interests. So far, equal rights between men and women have become statutory, even if there have been difficulties in achieving true equality.

Although the path to equality has already been established in laws and public discourses, equality measures are often challenging in daily public and private lives. Therefore, while women’s social status is improving in official sectors, new limitations on gender equality are appearing in more covert ways.

Past research on Korean women’s social status has focused in on specific areas, rather than in considering the overall picture. Examples of such research include: ‘Women’s Housework and Social Status’ (Sohn, 1989), ‘Social Status of Women in South and North Korea’ (Lee, 1999), ‘Comparison of Social Status between Korean and Chinese Women’ (Lee, 2001), ‘Change of Korean Women’s Economic Status and Role of Nation’ (Wu, 2006), and ‘Informatization and the Transformation of Women’s Social Status in Korea’ (Kim, 1998), among others.

Currently, although gender equality is accepted in the official discourse of Korean society, in practice many domains, such as education, labor, politics, and family, still show a traditional gender hierarchy favoring men. In order to achieve true gender equality through the improvement of women’s social status the characteristics of social status need to be analyzed, and a new action plan must be established based on this analysis.

This research traces changes in Korean women’s social status over the past 30 years, both before and after the enactment of the ‘Women’s Development Act’ in 1995, which sought a gender-equal society and a future direction towards improving Korean women’s social status, To achieve this, all aspects of status changes will be studied by dividing women’s social status into the areas of politics, economics, and human rights.

First, the change of women’s social status in the past 30 years through the statistics is examined and analyzed by classifying the laws and systems related to women as gender neutral, gender recognizing, and de-gendering or deconstructing the gender, focusing on its contents. Furthermore, this research will study the improvement of women’s social status and residual inequality by studying the gap between laws and reality in the gender division of labor.

The Change of Women’s Social Status in Korea

Definition of Women’s Social Status and Relationship with the Gender Equality

Social status means a comprised position in an entire society by the social respect or prestige given by people. Women’s social status is an ideological concept in the sense of belief, norms, and value regarding the social status and role of women in society, as well as a structural concept in the sense of women’s approach and position within the social system. This ideological and structural inequality is multi-dimensional, and such a dimension can be explained in various ways.

Geum-soon Lee defined women’s status as “status to get equal opportunity, participation, and the benefits in political, social, and economic systems in the society,” and herein women’s social participation is conceptualized in a broad meaning including economic activities, participation in politics and decision-making process, various socio-cultural participations and participation in unofficial sectors such as social organizations (Lee, 1999, pp. 8-9).

Bradley and Khor (Bradley & Khor, 1993, pp. 347-348) defined the status as “a phenomenon created from a social construction via differentiation and valuation processes, rather than natural and inherent characteristics which humans possess,” and considered that the status of men and women settled differently in the overall society as these processes were institutionalized between men and women. They approached the issue with a fine segmentation of women’s status between the public and private sectors, and subdivided each sector into economic, political, and social dimensions, in order to analyze the social inequality experienced due to the gender differences in various societies.

First, economic status is considered in terms of a legal composition related to women’s administrative position, poverty, labor rights as the public components of status, and in terms of an approach, control, and economic distribution of women related to the division of housework and economic resources of their households as the private components of status.

Second, Bradley and Khor consider the components of political status to be the systematization of women, the number of high-ranking women officials, the advantage of patriarchal and legal system against women’s rights, women’s right to speak in the family when making decisions, women’s sexual autonomy, and family violence.

Third, for social status, Bradley and Khor consider the ratio of women with higher education, women’s composition as sexual objects, rights of reproduction, investment in education by gender, women’s responsibility and role in regards of relatives, and average age of marriage Straus and Sugarman (Straus, Sugarman, & Giles-Sims, 1997, pp. 761-767) described the social status in relation with gender equality, which has become an index for economical, political, and legal equality, to understand whether social status as improved. Tarique and Sultan (Tarique & Sultan, 2001, pp. 1112-1123) have considered the division of social status along dimensions of violence against women, economy, education, and politics. Herein violence against women shall be the basic principle to explain women’s social status in terms of human rights, the rights to lead a decent human life with dignity, since it includes sexual or family violence and prostitution.

Women’s social status means the typological interaction which spreads out to the whole society, and position of men and women within society. This research uses social status with a broad meaning by considering that social status is not separate from other forms of status in the legal, political, economical, or educational systems, but rather it is considered to include all forms of status in each system of political, eco nomical, human rights, and other systems. However, it is important to understand what level of social status is actually realized by women by investigating the engagement levels in each area of society, along with understanding the direction of policy towards the improvement of women’s social status or gender equality (Lee, 2001).

Most importantly, the level of improvement in women’s social status links to gender equality, and based on this the direction and characteristics of policy related to women can be identified. Gender inequality means a difference of status, power, and authority that both genders can exert in various contexts. A decrease in gender inequality means the reduction of a major dimension of inequality, which is more concretely defined in aspects of the legal system. But, the change is unequal, so that does not mean it would result in uniform improvements in all women’s lives. That is, a decrease of gender inequality simply means a meaningful reduction in the net disadvantage of women compared to that of men (Esping-Andersen, 2009). The measurement of changes in women’s social status can be achieved in many different ways. One way that these changes can be measured is by how much women participate in activities within each domain of society. Women’s participation can be compared with that of men through statistics. The social status change of women can be determined by the policy promoted by the laws and systems in place in society. Most notably, the direction of policies related to women is aligned with a practice of gender equality through the content of related laws.

However, gender equality is a complex multi-dimensional concept and should not be limited to the guarantee of equal opportunity. Rather, it true gender equality brings an equal condition, and even further achieves equal consequences for women relative to men. First of all, equality starts from achieving equal opportunity, which leads to equal access to political and social opportunities, and even includes protection, preferred treatment, and active measures promoting women. For protection and active measures, it can be a somewhat contradictory principle to equal opportunity since it is an equality that uniquely favors women. However, it is important that none of these principles are outside of the logic of quality (Cho, 1996, p. 263).

Chamberlayne (Chamberlayne, 1993, pp. 171-175; Sainsbury, 1997, pp. 173-174) as proposed several models towards understanding the characteristics presented in the relationship between gender equality and policy.2

1) There is a gender neutral type which ignores the different positions of men and women under different circumstances. This type has almost no consideration of the distinct characteristics of women’s perspective, and regulates social legislation once again towards official equality for both genders.

It is assumed that the equality can be achieved only when gender differences are considered by gender recognition, which seeks for a public solution with its focus on removing obstacles that disrupt women’s equality. Gender recognition requires establishment of quotas and the reduction of burdens resulting from the care of for children, the disabled, and senior citizens as a measure of active discrimination, as well as the support of supplemental public systems such as shelter, counseling centers, and hotlines for issues of sexual and family violence.

2) The gender reconstruction and deconstruction (or de-gendering) type refers to requiring role change between men and women as a precondition of equality, and it demands care, equalization of compensation for labor, parental leave, and vacations. Initially, additional basic changes, such as changes to patriarchal laws and political systems that are not limited to changes of men’s perception are needed in order for gender reconstruction to take place. Secondly, there is a demand for changes in labor characteristics, organization, and social security based on the male-dominated employment structure, which means changes to the patriarchal social structure. Thirdly, parental leave needs to be paid from public expenses, which requires a considerable budget from the government. Thus, gender reconstruction needs to consider changes at a structural level a precondition to change in a private level. This type is also called de-gendering by Fraser, since it pursues equality via changes of the gender division of labor.

The Change of Women’s Social Status through DataThe Change of Women’s Social Status through Data

Changes in women’s social status can be assessed using social sta tistics and indicators related to women, and the level of equality can also be determined based on the degree of women’s level of participation in various fields of society relative to that of men.

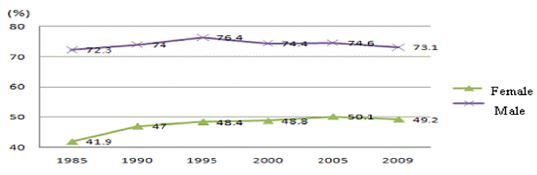

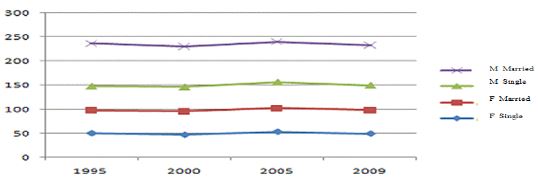

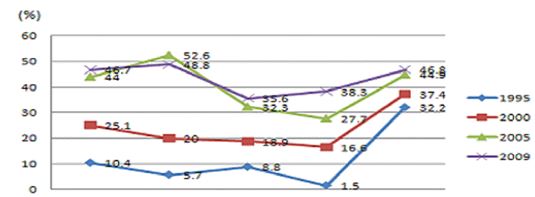

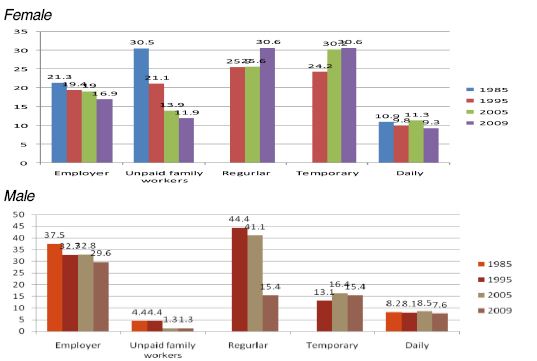

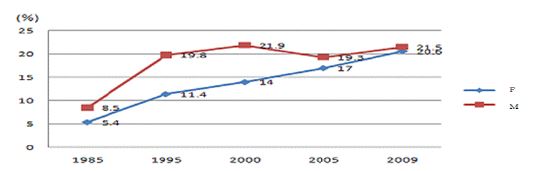

Economic participation is analyzed based on characteristics of women’s economic activities, current employment status, job stability, and participation in decision-making process in order to understand women’s employment structure. The female population of economic activity reached 10,076,000 in 2009, and has thus entered the era of ten million women engaged in economic activity. The ratio of women engaged in economic activities was 41.9% in 1985, 48.4% in 1995, and 50% in 2005, but had reduced to 49.2% as of 2009, as shown in figure 1. The gender difference in participation in economic activities remained quite large, with women’s engagement rate 23.9 percentage points lower than that of men, which was 73.1% in 2009. When separated based on marital status, the rate of economic participation of married women was found to be 41.0% in 1985, 47.6% in 1995, and 49.0% in 2009, showing a gradual increase (See Figure 2).

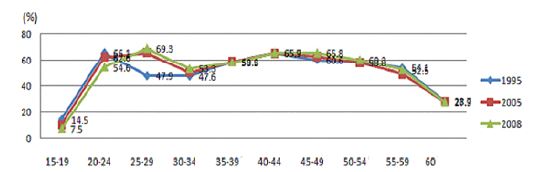

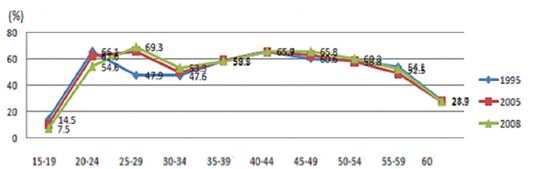

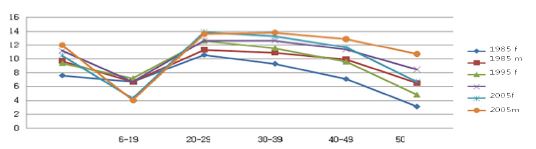

However, the women’s withdrawal from the workforce due to child birth and childcare continues, despite the growth of women’s participation in economic activities. In 2009, the ratio showed the typical “M pattern” with the ratio of economic participation by women. While the age group of 25-29 showed the highest ratio (69.0%), the ratio decreased dramatically to 51.9% for the 30-34 age group. Since then, the number of women who have re-entered the labor market has increased (65.4% for age group of 40-44, 65.4% for age group of 45-49), then drops again for the older population categories (See Figure 3).

Among female employees, the ratio of women with professional administration, professional, or management positions showed an increase after 1980, as shown in figure 4. The gender difference in these categories was 9.1% in 1997, but has been reduced to 0.9% as of 2009. There remains a gender disparity in wages, with women’s wages only 63.2% of men’s as of 2008. Despite the difference, the gap has been declining since 1993, but women’s wages still remain as low as 60% of men’s wages since 2000 (See Figure 5).

Participation Rate in Professional Administration Public ServiceNote. Korean Women’s Development Institute (2010)

Women’s political participation is important to any assessment of how influential women can be in politics. In this research, the status of women’s participation in the government offices is considered, especially women’s advancement into decision-making positions and their political participation.

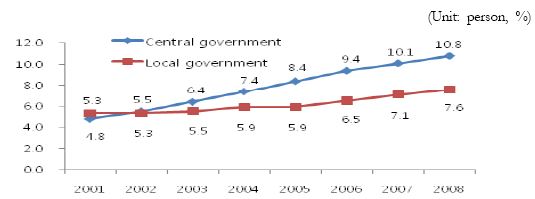

First, in terms of the representation of women in the National Assembly and Local Councils, the ratio of women in the National Assembly has been gradually increasing as shown in the Table 1. In the 18th Congress, 41 out of the total 299 congress members (13.7%) were women in 2008. As of 2006, local councils had 14.5% women, showing a rapid growth since its effective start in 1995.3 The ratio of women in the government and municipal committees shows that the number of female members is increasing in both the central government and the local municipalities. The ratio in the central government was 10.8%, while the ratio in the local municipality remained a single digit as of 2008, at 7.6% (see Figure 6).

Second, it is important to increase women’s ratio in public services in order to achieve the representativeness of women and formulate equal policy for women’s rights and interests in public positions. In 1999, the ratio of female public officers was 29.8%, although most of them were in the junior levels of (6th or lower). And, women in the 5th or higher level positions who participated in the decision-making process were only 3.0%. The status of female public officers in management positions of the 5th or higher level was 10.8% in the central government and 7.6% in local municipalities. This shows that although women’s ratio in management positions in public services has been continuously increasing, it remains below 10% in local municipalities (See Table 2).

Third, as shown in the Figure 7, the ratio of successful women candidates in the national exams in 2009 was higher than that of men with 41.2% for the Foreign Service Exam and 48.8% for the Civil Service Exam. Women’s ratio of successful candidates on the bar exam, has increased dramatically since 1995, but the ratio in 2009 35.6%, which represented a 2.4% decline compared to the previous year.

Women’s rights and interests is a concept which includes domestic violence, sexual violence, and prostitution, all of which fundamentally violate human dignity. The definition of ‘violence against women’ was introduced by the 85th UN General Assembly in December 1993. It is defined as a violent behavior based on gender, which has brought or could possibly bring physical, sexual, or psychological damages or pain against women in private or public life according to Declaration 1. It also includes behaviors such as threat, coercion, and voluntary deprivation of freedom (Lee, 2008, p. 25).

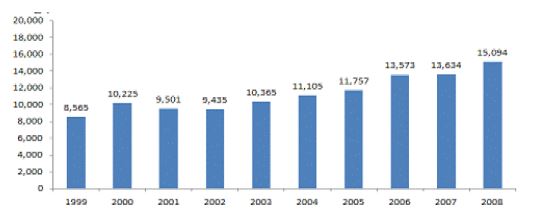

Currently, Korean society includes the female victims of violence as the supporting target of domestic or sexual violence and prostitution. In the case of sexual violence, the number of sexual assault cases in 2002 was 9,435, and it has been continuously increasing since then, as indicated in the Figure 8. The number of cases increased to 15,094 in 2008, which was about 60% higher than in 2002. In case of cyber sex, assault cases of distributing obscene materials online showed a considerable increase with 3,435 in 2005, 5,435 in 2006, and 7,796 in 2007 (Korean Women’s Development Institute, 2009, p. 448).

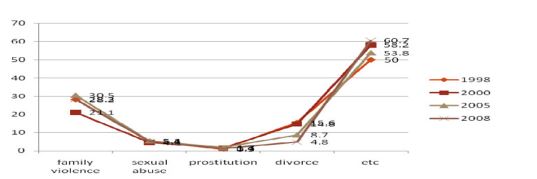

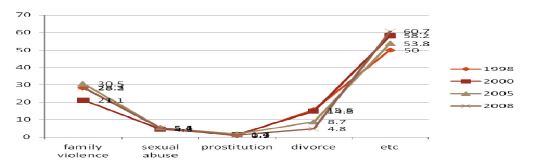

Various types of counseling were provided for women through the women’s hotline (1366) in 2009. 30.1% of counseling requests were related to domestic violence, 4.8% related to sexual violence, 1.2% related to prostitution, 3.6% related to divorce, and 60.3% miscellaneous requests. A 30% level of domestic violence was reported in 2005, but sexual violence remained at 5% in the same year, and showed a decreasing trend to 4.8% in 2009 (See Figure 9).

Regarding the penalty placed on domestic violence offenders, the number of cases increased from 9,149 in 1999 to 15,271 in 2002. Since then, it has showed gradual increases until 2006, when the numbers decreased to 13,531 and a subsequent decline to 12,807 in 2007 (Korean Women’s Development Institute, 2009, p. 446). The current state of prostitution indicated in the Table 3 also shows a decreasing trend. The 329,218 women working in prostitution in 2002 was reduced to 269,707 in 2007, and annual number of clients of prostitutes decreased from 168,840,000 to 93,950,000 over the same time period. However, internet and other types of prostitution have increased as the number of women in prostitution increased from 79,012 to 118,671, and their clients also increased from 40,520,000 to 41,340,000.

The Change of Women’s Social Status through Laws and Systems: from Gender Neutrality to De-gendering

Korea has tried to utilize women primarily as low cost labor, and no policy has existed to improve the gender inequality related to women’s social status until the mid 1980s. These government policies faced a challenge in the 1980s along with a pro-democratic movement related to progressive women’s organizations. These organizations made an earnest effort towards achieving equal rights for women through their relationships with the government after the late 1980s. According to Table 4, the following reforms of laws and systems for gender equality have occurred since the 1980s:

First, focus was put on policies supporting women’s participation in the workforce. Examples of this include the integration of a women’s development plan into national planning, the enactment (1987) and amendment (1989) of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act, and the enactment of the Infant Protection Act (1991). These examples are drawn from both before and after the administration of Roh, Tae-woo following the democratization that occurred between 1987-1992.

Second, from 1993-1997, the administration of Kim, Young-Sam established a basic direction for women’s policy which had almost no interest under the authoritarian government. In 1995, the Women’s Development Act was enacted and provided an institutional framework for the systematic improvement of women’s overall status. Affirmative action was enforced by the introduction of an employment target system for women public officials he Family Violence Prevention Act was also enacted, which dealt with violence against women.

Third, in 1998, the administration of Kim, Dae-Jung established a Special Committee on Gender Equality and reinforced Korea’s women’s policy by reorganizing the Gender Equality government administration in 2001. The Gender Discrimination Prevention Act was enacted in 1999, and an approach towards gender recognition related to women’s policy was made by placing attachés for women’s policies in 5 departments. Specific plans for dealing with women’s employment issues, such as the women’s employment target system and measuring the unemployment of women were established. In addition, the nomination quota of 30% for women was enforced through the amendment of the political party law, which provided an opportunity for the expansion of women’s political participation.

Fourth, during the administration of Roh, Moo-Hyun in 2004, the patriarchal family system was abolished (2005) and the Law of Prostitution Prevention (2004) was enacted to discourage violence against women. The Ministry of Gender Equality was expanded to become the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family and later adopted the gender impact assessment system in 2005. This ministry adapted a budget guideline system for gender recognition (2008) which helped to establish a foundation for the policy of gender equality which supported the identification of gender differences.

First, there has been the establishment of a de-gendering type through the abolition of the patriarchal family system and the gender recognition that came with the enactment of Women’s Development Act, the establishment of Ministry of Gender Equality, the introduction of the recruit quota of Cadettes, the amendment of the political party law, and the nomination quota of 30% for women in the laws and political sectors. The system has also allowed the admission of women into the military, air force, and naval academy which had been exclusively male in the past.

This is related to the gender disparity in the level of higher education at present, and the predominance of women in certain college majors, such as colleges of education, arts, physical education, and liberal arts, have not improved for they were already considered as women’s domains in traditional gender roles. Meanwhile, only 8.7% of women have majored in Engineering. The government has been driving policies to encourage the establishment of engineering colleges in women’s universities to improve these numbers. In particular, the admission of only 10% to its maximum capacity was allowed to women in the air force academy (1996) and the military academy (1997), which have limited opportunities of access for women. And, only 4.2% were allocated for women at the police academy (1989).

In 2001, women’s influence was expanded regarding various national and systematic mechanisms impacting policy decisions, such as the establishment of the Ministry of Gender Equality, the establishment of attaché offices for women’s policies in 6 departments, and the guarantee that 30% of representatives in each departmental government committees would be women, as aligning them with the National Assembly Standing Committee. And, through the amendment of the political party law, the ratio of women members was increased to 13.5% of the National Assembly in the 2005 election through the help of a 50% quota for the female proportional Representatives, implemented in the 17th general election in 2004.

Second, the amendment of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act occurred at the same time as the enactment, due to the recognition that the gender equality the Act aimed to achieve was incomplete and lacked substance. Since that initial amendment, the Act has been amended many times.

The initial contents of the Act that was enacted in 1987 showed gender neutrality and gender recognition with guarantees on the recruitment and enforcement of maternity leave. However, the maternity leave portion showed limitations in reflecting the scope of the gender division of labor since it only applied to women, considering that “women have an important role in childbirth and childcare.” During the enactment of the law, there were objections from the employers’ Federation and from congressmen.

The first amendment in 1989 clearly stated the characteristics of gender recognition by including maternity leave in the length of service, as well as the types of gender neutrality by adding maternity leave, equal work in equal business, and the application of equal pay. The second amendment in 1995 showed the types of gender reconstruction with the implementation of paternity leave for the spouse, and the third amendment in 1999 showed the characteristics of gender recognition by including in the articles the definitions of indirect discrimination and sexual harassment in the work place.

In particular, sexual harassment in the workplace can be considered a factor of the labor environment that affects women’s economic participation is the third amendment, which contains this provision, represents an effort to correct the male dominant sexual culture which recognizes women as a sexual object, which is deeply related to the inequality issue in women’s employment.

The fourth amendment, enacted in 2001, showed de-gendering characteristics which included the change in men’s role, such as the work life balance, the promotion of employment, and the policy to guarantee returning return to work after maternity leave, along with the social insurance to bear the expense of maternity leave. It also mentioned the parental leave for both parents as the purpose of amendment.

Thus, a policy was proposed to resolve the childcare and housework differences at a national level, and to provide the social insurance to bear the partial expense of a working woman’s maternity leave. This provided momentum to change the existing roles related to the division of labor which categorized childbirth and childcare under a private domain into the public domain which now categorized childbirth childcare as a social cost. This social cost of childbirth and the transition to the system of parental leave can be considered a de-gendering institution.

The Fifth amendment enacted in 2005 stipulated support for the full amount of the vacation bonus before and after the childbirth, and showed both the gender recognition and de-gendering types in the sixth amendment in 2005, which established an extended period of use for maternity leave, up to 3 years after the birth of the child. Further, the eighth amendment, following the seventh amendment in 2007, renamed the law as the Law of the Equal Employment Opportunity and Support for Work-Family Balance, and added articles for the spouse’s maternity leave of 3 days and programs for women’s vocational development and employment promotion after a discontinued career.

The enactment of laws supporting the economic participation of women has contributed to changing the consciousness of sexual discrimination and easing discrimination in employment. The increase of women’s length of service in management and professional positions and the increase of women workers with higher wages, can be considered as an effect of the laws and systems related to the promotion of women’s labor, such as the Equal Employment Opportunity Act.

Third, through the change of gender equality types in the enactment and amendment of laws related to violence against women, such as sexual or domestic violence and prostitution, the Law of Criminal Penalty of Sexual Violence and Protection for Victims (the ‘Special Act on Sexual Violence’), which was enacted in 1993, could not change the rules of criminal law, which considered sexual violence (such as rape and sexual molestation) as an outdated and patriarchal ‘crime related to chastity.’ However, it also included gender inequality as an offense subject to the complaint. The major portion of the proposed draft by the feminist movement was nearly not accepted, and it was generally limited to law practices and existing conventions of sexual violence.

In the first amendment of the Special Act on Sexual Violence, enacted in 1997, the definition of sexual crimes was amended by changing the terms such as ‘crime that hurts the custom’ to ‘crime that hurts the sexual custom’ and ‘crime of chastity’ to ‘crime of rape and molestation.’ However, the amendment was only partial and excluded the establishment of new articles for sexual harassment altogether. It changed type, representing gender recognition rather than gender equality, since it clearly stated that the sexual violence is not a matter of an individual woman, but rather a matter related to all women.

In 1997, the Special Act on Criminal Penalty of Family Violence and Law of Family Violence Prevention and Protection of Victims (the ‘Family Violence Prevention Act’) was enacted. In its contents, a neutral wording of ‘family violence’ was used instead of ‘beating one’s wife,’ so that it would have a gender-neutral characteristic in which the violence against women can be recognized as domestic violence.

Then, the first amendment, enacted in 1999, readjusted the demarcation of public and private matters by publicizing the previously private matter of domestic violence. This can be looked at as the law approaching the gender reconstruction type, since it clearly stated that domestic violence is a social crime in which the nation needs to intervene. It has become possible to order legal correction, rehabilitation or penalty to domestic violence offenders, and this brought an attitude change toward the related organizations, such as in the settlement of education and exams for police officers as a target. This, however, requires fundamental changes in the system for men or to the underlying patriarchal system.

Besides these, three major laws for women’s rights, such as the ‘Law of Criminal Penalty for Pimp’ and the ‘Law of Prostitution Prevention and Protection of Victims,’ have been enacted over the last 10 years since 2004. Although they have been facing opposition from men, prostitution has clearly become statutory as a social crime, together with sexual violence and domestic violence. Furthermore, the penalty for perpetrators and the nation’s responsibilities in these areas are also being reviewed.4

The enactment of laws related to the improvement of women’s social status and gender equality often faces various kinds of opposition by the patriarchal forces, and often gets enacted with numerous limitations, rarely resembling the original demands of women throughout the process of enactment and amendment. Therefore, the laws for women end up facing a demand for additional amendment immediately after they are enacted. This shows that gender-neutrality is changed to gender-recognition or de-gendering with the changes in these laws.

However, laws related to women appear to be at some point within the types depending on the subject of the law, and change of gender equality types can be found by the process of enactment and amendment of laws. These gender equality types make a clear position for women’s social status, and they can be the criteria for the study of changes in women’s social status. Also, changes towards gender equality can establish strategies promoting gender equality for the future, and provide useful direction for the improvement of Korean women’s social status.

Does Women’s Social Status Progress or Is It an Optical Illusion? Gap between de jure Equality and de facto Equality

For the last 30 years, there has been no dispute that Korean women’s social status has improved throughout the society in politics, economics, and women’s rights. The enactment and amendment of women-related laws and systems, has helped to make major steps forward on the fundamental areas affecting women’s social status, through an easing of gender discrimination in each sector of society and contributing to changing the consciousness of gender discrimination. However, gender inequality that remains in Korean society has brought the degree of actual improvement in women’s social status into doubt. Thus, this research studies whether the improvement in Korean women’s social status is an optical illusion or a true improvement, through gap analysis of the laws and institutional equality and the true equality in society.

The Hidden Side of Progress in Women’s Social Status through Data

Many limitations have been shown in securing stable income perspectives, whereas women’s social status has been improving through the economic participation of women and the reduction of wage differences between the genders. In addition, the use of temporary positions and gender segregation in jobs can be considered as additional limitations.

First, the participation ratio of women in economic activities has shown a rapid increase from a starting point of 45.0% in 1988, which was the first year of enforcement of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act. The ratio exceeded 50.0% for the first time in 2005, but it was at a standstill after the late 1990s due to the Asian economic crisis. Women’s economic participation in 2009 stood at 49.0%, and it has not been significantly different from women’s level of participation in political activities from the mid 1990s to present. The phenomenon of career discontinuity remains due to pregnancy and childbirth affecting the labor market, as childbirth has been showing a decisive effect on women’s economic participation.

Importantly, the instability of temporary employment, such as interim positions, hourly positions, service positions, and small subcontractor positions, is increasing behind the increase of women’s employment when compared with that of men. With the speed-up of flexibility in the labor market, the gender discrimination with women-first layoffs after the IMF, the foreign exchange crisis in 1997 and the enforcement of the dispatched labor system in July 1998, 4.2 million women have been in temporary positions, which has been 70% of the entire female workforce. And 98.7% of these have been in interim positions (Cho, 2010, p. 12). Additionally, the proportion of female workers in temporary positions with hourly, interim, temporary, and housework has been increasing due to involuntary reasons, such as discrimination in employment, as well as voluntary reasons, such as childcare and family care.

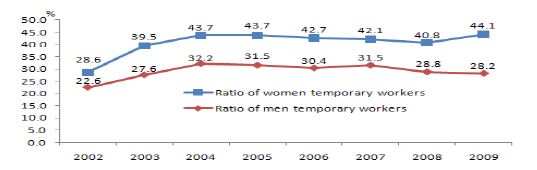

The rise in temporary employment leads to a decrease in stability of employment, and the number of temporary women employees has been continuously increasing since 2002. On the other hand, temporary men employees have been decreasing, so the gap between men and women is growing (See Figure 10).

For those interim positions among the temporary positions, the female interim wage workers rapidly increased from 24.2% in 1995 to 44.1% in 2009, whereas the male interim workers increased only 2.3% from 13.1% to 15.4%, which has created a 28.7 percentage point difference between men and women (See Figure 11).

The unemployment rate for women was 2.4% in 1985, 1.7% in 1995 and 3.0% in 2009. Women’s unemployment rate showed an increasing trend after 1995, indicating that many women have returned home from work due to layoffs in the labor market after the IMF foreign exchange crisis in 1997. The unemployment rate for women showed a declining trend, but it increased greatly within a single year during 2009. The unemployment rate of unmarried women also increased greatly by 6.6% (See Table 4).

Third, we also see the phenomenon of gender segregation related to the occupations in the labor market. The characteristics of women’s occupational categories and status at work can be a good indicator for women’s economic participation. The ratio of women’s occupational activities has been increasing, but the jobs have continuously been distributed unequally. Although women’s standing has improved in the labor market, just as the professional ratio has increased for women with higher education there is a very distinct trend towards convergence to office and service work based on the gender division of labor. Women’s employment is primarily engaged in areas of social and personal service, and those areas often tend to be disadvantaged in technology, rank status, job stability, and wage.

With respect to wages, women’s wages are still paid at a much lower level than men’s, even with the minimum wage system that was adopted in 1988. The wage disparity by gender shows that it was eased during the 1990s, but the reduction of wage disparity has been at a standstill ever since the foreign exchange crisis of 1997. This is because the wage disparity reflects multiple factors, including the simple and repetitive characteristics of women’s job categories, the low average age and education level of women workers, the short employment history, limited opportunities for promotion, and an unequal wage system.

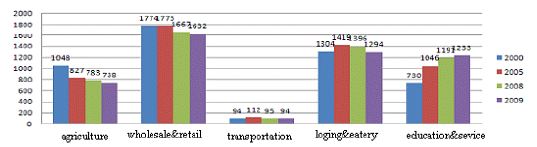

As shown in the Figure 12, women are mainly engaged in wholesale and retail sales, lodging, restaurants, educational services, personal services, health and social welfare, self production, and consumption in industrial distribution where there are more women than men. On the other hand, men are primarily engaged in construction, transportation, finance and insurance, professional science and technology services, public administration, national defense, and social welfare and administration. This pattern of employment shows gender bias. Women’s ratio in the distribution of employment by occupation was 50.8% in sales, 66.2% in services, 46.7% in office clerks, and 51.6% in simple labor work, whereas it was only 8.6% in management, 14.6% in technician, and 11.7% in machinery operation and assembly.

As a result of these statistics, most women do not secure welfare benefits reflecting the measure of social risks due to their unstable income from temporary positions, low wages, and benefits that are focused on permanent positions. In particular, the benefits of childbirth and maternity leave are mainly guaranteed for full-time women employees in large corporations and enterprises. There is a large disparity is the benefits of childbirth and maternity leave based on the size of a business. This results in two women employee groups in one nation, with a stratification of permanent and temporary jobs for women laborers, since many women are mainly hired by small businesses with less than 10 employees and results in a disparity in welfare benefits among the women laborers.

Fourth, despite the increase in women’s participation in economic activity, women are still in limited decision-making positions. According to figures of women’s employment published by the Ministry of Labor in 2006, it is hard to find women in executive positions in government agencies or government affiliated offices. The ratio of women in executive positions was only 1.02% in investment institute and 2.96% in affiliated organizations, where it was 3.48% in private companies. Among the 14 government investment agencies, only 1 woman executive existed in the Korean Railroad. 83 government affiliated agencies out of 93 were found without any women executives (Park, 2010). Table 5 shows that less than 1% of women executives existed in the top 10 domestic companies that are listed as public companies as of February 2010, in terms of market capitalization, and there were 6 companies without any women executives at all.

This shows the power of the ‘invisible wall’ is still great although visible discrimination has been reduced in women’s employment. The improvement of Korean women’s economic status may be an optical illusion, since women taking decision making positions is still scarce due to a glass ceiling that obstructs promotion of women beyond a certain level.

Women’s Political Participation, Poverty in the Midst of Plenty

Women’s participation in politics and decision-making positions is expanding due to the establishment of conditions to extend women’s role as the local government was resumed in 30 years. The amendment of the political party law in February 2000 has established a quota system promoting the official nomination of women, which required the parties to nominate 30% or more women candidates as proportional representatives in local elections and the National Assembly, resulting in 11 winners for the nationwide seats and 5 district seats in the 16th general election, the most in history. After that, female members of the assembly have increased continuously to 13.0% in 2004 and 13.7% in 2006. The women’s ratio in metropolitan assemblies was 12.1%, and in local government 15.1% as a result of local elections in 2006, a remarkable improvement compared to the 0.9% that existed in 1991.

However, Kanter explained that the women’s ratio of total members in an organization should be 15% or higher in order to be truly efficient, and that women’s demands would be held back and their benefits would be ignored until this level was achieved. At 15% representation, the women members in an assembly would be able to take legislative action and exert influence in support of specific matters of concern to women members (Kim, Yang, & Jung, 2009, p. 172). At this point, women’s participation in current political sectors as members of the Congress or local municipalities is increasing, but it is still showing a numerical limitation.5 Furthermore, women’s participation is gradually increasing in administrative departments that have the actual authority, but it is still in a weak standing in decision making positions in comparison with men’s, as shown in the Table 6, ‘Status of Women’s Participation in Government Assembly’ and Table 7, ‘Status of Administrative Public Officials in the 5th or higher ranks and women officials.’

In general, women’s political participation has shown an increasing trend over the last 30 years, and yet it remains at just a single digit number in its ratio. Additionally, women’s entry into high ranking positions is low compared to that of men. In order to create a society in which both men and women participate equally and are responsible for and reflect women’s demands in government policies, women’s participation ratio should increase to at least 30% in the National Assembly, municipal and local governments, and in various official positions. Currently, it has only reached much lower level in these areas, except in national examinations.

Gap between Women’s Law and Reality

As discussed earlier, the Equal Employment Opportunity Act provides for maternity leave before and after the childbirth to protect the maternal instinct and paternity leave of 3 days for spouses of women workers are provided, and women workers who have infants and children under age of 3 can use the maternity leave in order to promote strong work life balance. As shown in Table 8, women’s maternity leave and vacation before and after the child’s birth is being increased in accordance with the enactment of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act. Men’s paternity leave is also increasing, but it is still lower than that of women, and only 355 men used this benefit in 2008. For working parents, Article 21 of the Equal Employment Opportunity and Support for Work-Family Balance System Act and Article 14 of the Infant and Child Care Law mandate the establishment of a worker’s child care facility for companies with 300 full-time women employees or 500 total employees. There have been 440 companies with such child care facilities as of 2008, and the ratio of compliance with this regulation has been increased from 27.5% in 2005 to 49.3% at present, however only 28% of the child care facilities most needed by the workers have been established (Hong, 2009, p. 132).

Secondly, the laws and system of women’s human rights, such as those relating to sexual or domestic violence, and prostitution, have brought many side effects and problems due to poor execution and administration of the laws. The ratio of prosecution is only less than 50% for sexual violence due to the male-dominated judicial customs, and there are limits on the penalties that assailants receive and victim protection from the domestic violence due to the basis to attempt to keep the family together (Lee, 2008, p. 29).

Law enforcement against prostitution is also facing resistance and distorted enforcement of the laws due to the social brand of prostitutes, the long back-scratching relationship between law enforcers and criminal subjects, and the long social customs which have tolerated prostitution as a necessary evil of society. In the case of prostitution, the law is facing new resistance and challenges of spurious right to live since it was enacted during the process of building the new gracious ruler centric value in Korean society along with the materialistic principle (Cho, 2010).

Therefore, laws to prohibiting violence towards women have been enacted, but proactive modification of systems is needed in order to overcome the reality that the violence towards women has not been significantly reduced.

Newly Intensified Gender Division of Labor and Unfinished Gender Equality

A new limitation on gender equality is emerging underneath the surface, where it appears that women’s social status is improving in public sectors.

First, the masculinization of women’s life course and the newly strengthened gender division of labor can be considered. Women’s education and employment are the core factors of women’s role changes. As shown in Figure 13, the gender gap for average years of education is decreasing for the age group of 20-30. Also, it has been shown that women are surpassing men in higher education. That is to say, the ratio of college entrance in Korea was 52.8% for men and 49.8% for women in 1995, 82.9% for men and 81.1% for women in 2006, and then it reversed to 81.6% for men and 82.4% for women in 2009 which resulted in a higher proportion of women attending college as compared to men (Korean Women’s Development Institute, 2009, p. 189).

Average Years of Education of Men Compared to WomenNote. Korean Women’s Development Institute (2009)

When looking at different age groups for the economic participation ratio, the different ratio for each gender’s participation, that is to say the women’s participation increases where the men’s decreases, has been gradually decreasing for the age group of 20-30 (See Figure 14).

Therefore, as the length of women’s educational period has increased and the ratio of their participation in labor market has increased, the gap between men and women has gotten smaller, and thus we are seeing phenomenon of masculinization of women’s life which is unlike that of the past.

However, a new type of gender inequality has been brought by housework without the work-life balance although the economic activity of women is gradually increasing. Working women still manage the majority of housework and the education of children also remains the primary responsibility of women.

As shown in Table 9, wives in dual-income households spent an average of 3:29 a day to take care of the family, whereas the husbands spent only 32 minutes as of 2004. This remained almost the same in 2009, as the wives spent 3 while the husbands spent 37 minutes.

As shown in the Table 10, The Survey of Opinions for a Division of Housework, the ratio for the category of ‘mainly wife will do’ has been gradually increasing, compared to that of ‘divide up fairly.’ Also, only 11.8% of husbands and 12.0% of wives of dual-income households replied that they practice a fair division of housework in real life, according to the recent report of the National Statistics Office (2010).6 In this respect, the gender division of labor in terms of housework seems to still remain unbalanced in dual-income households.

Therefore, we can see that women’s role has been rather increasing as the existing type for gender division of labor changed from ‘men-work, women-family’ to ‘men-work, women-work and family.’ This could mean that there has been almost no resolution found for women’s tension of being both a mother and a worker as of now. This has led to a masculinization of women’s life through the extension of the period for women’s education and economic participation, while a new phenomenon of gender division of labor has been shown as the burden from work increased, since women are in charge of housework whereas there has been almost no participation expected of men.

Current participation ratios of married women’s economic activities decreased to 49.8% in 2009, whereas it showed a continuous increase of 41.0% in 1985, 47.6% in 1995, and 53.6% in 2005. The participation ratio for married women showed a very big difference of 32.2% from the men’s participation ratio. Married women’s employment rate reached a peak at around 50% and this indicated that the change of women’s role has been imperfect. It meant, at the same time, there continued to be many women continuing to withdraw from the labor market as they got married.

Secondly, there is an increase of the double burden of work for women due to the inadequate support of acceptable work-life balance can be considered. Korea adopted the parental leave system and it then became possible for both men and women employees to request parental leave in 1995, and it also become mandatory to establish worker’s child care facilities in workplaces with 300 or more women employees or 500 or more total employees. This was to support the work life balance system7 due to the continuous increases in the number of dual income families.

The current status of the provision and the usage of childcare services showed that there are total of 33,499 childcare facilities as of 2009, and they are categorized into 1,826 public facilities, 14,275 private facilities, 15,525 family daycare facilities, and 350 worker’s childcare facilities. In other words, the supply ratio of private facility was 89% where the public facility was much lower, at only 5.5%.

The predominance of private services in the usage of childcare centers is currently 10.9% for the public facilities and 77.6% for the private facilities (Hong, 2009, pp. 133-135). Privatization of child care facilities has been laying the burden on the families, and has added the difficult of maintaining work to married women.

Policies have been adopted to promote the use of parental leave, and a nursing leave system for public officers has also been implemented. It guarantees 60 days of paid maternity leave, the transition to lighter work during pregnancy, and limits overtime to protect maternal instincts among women laborers.

However, the government has promoted a corporate regulation policy for the expansion of worker’s child care facility in order to encourage companies to hire women. But, this policy has had weak compulsory aspects, so it has been difficult to realize the desired gains. It has also produced a differentiation in claiming rights for social welfare, which has only been offered to full-time women employees hired by large corporations or enterprises due to the nature of Korean labor market. According to a recent survey, only 10% of women reported that they had used the maternity leave (YTN, 2010).

In addition, this policy has imposed a burden of maternity protection related to the cost of the business owners, so the matter has extended to maternity leave which has been the main cause for avoiding women’s employment (Wu, 2006). The reality of most women experiencing difficulties from job and housework due to a gap between the current situation, the laws of maternity protection and the support for the work-life balance may yield a fact that it is a kind of optical illusion where the improvements in women’s social status has been limited to certain groups of women only.

Third, the increase in violence against women should also be considered. Violence against women, such as sexual violence, sexual harassment, and domestic violence has not been reduced due to the masculism which remains even today, especially in domestic violence. The number of calls requesting counseling using the women’s hotline (1366) in 2009 was about 190,000, representing a 20% increase from just one year prior, and the contents of counseling showing the ‘domestic violence’ was at the top (See Figure 15). However, it has been difficult to conclude that the violence against women is increasing due these factors. Previous victims have been courageously representing themselves in situations where they would have endured the pain with fear and in silence in the past.

International Position of Korean Women’s Status

Historically, the change of Korean women’s social status has been studied in the realms of politics, economics, and human rights. In relation to these areas, the gender equality index makes it possible for an international comparison to understand the standing of the Korean women’s social status in comparison with other countries (Chun, 2009).

First, the Gender-related Development Index (GDI) is used to measure the gender gap in terms of the average capacity for development measured by the human development index. Average life span, literacy rate, K-12 school enrollment rate, and income ratio (actual GDP per person) are also used in the measurement. Korea ranked 31st in 1996, 28th in 2005, and 26th in 2009.

Second, the Gender Empowerment Measure (GEM) is a measure focused on the opportunity, rather than the role, of women, and the ratio of women members in the Assembly is used as a measure of the political participation and power in the decision-making process; the ratio of women in administration and professional roles is used as a measure of the economic participation and power of decision-making process; and the relative ratio of wage is used as a measure of the authority over economic resources. The GEM is an indicator to measure the participation in important social sectors which has been indexed for women to participate in decision-making process of political and economic sectors.

This indicator is not always matched with the degree of a nation’s economic development or human development. Economic or human development does not automatically improve women’s authority; it only alludes to the fact that separate national policy is needed to promote equality. When we measure women’s ratio in assembly, administration and management positions, professional technology positions, income differences (income distribution), and the other factors. Korean women ranked 78th in 1996 and 59th in 2005. The GEM in 2009 showed the ratio and influence of leadership among Korean women, in which they ranked very low among the 134 countries considered. They ranked 69th in women assemblies, 102nd in women administration and management positions, and 89th among women professionals.8 According to the “Proactive Remedial Action for Employment” announced by the Ministry of Labor in December 2008, it showed women’s ratio of 5.7% for executives, 12.6% for managers or of higher positions, and 40.1% for women in lower than managerial positions in business with 1,000 or more employees.

Third, the Global Gender Gap Index (GGI) is measured by economic participation and opportunities, educational achievements, health and subsistence, and authorization of political rights. It showed that Korean women ranked very low, ranking the 97th in 2007 (115 countries), the 108th in 2008 (115 countries), and the 115th in 2009 (134 countries).9

The social status of Korean women, in general, and the level of women’s human resource development (GDI) was relatively high, but relatively low for women’s social participation and the gender equality level (GEM and GGI) compared to other countries.

Conclusion: The Change of Women’s Social Status and Residual Inequality

Up until now, this research examined the change of Korean women’s social status over the last 30 years, both before and after the enactment of the Women’s Development Act in 1995. Social status is a social form of differentiation and value assessment, and the status of men and women are positioned differently. Thus, social status is not naturally granted, but it shows the vicissitudes of society. Women’s social status appears in overall society, and this research considered type variations of gender equality as status changes in politics, economy, human rights through statistics, and status changes through laws and systems.

By tracing Korean women’s social status improvement over the last 30 years, it was shown that women’s social status has become practically equal to men’s in many social sectors, such as in occupation, legal rights, education, political participation, and other areas. However, despite all this evidence of official equality, it still raises questions about the true nature of the improvement of women’s social status and the gender-equality due to the remaining inequality, such as the scarcity of women in professional fields, the prevalent imbalance of housework, and the increase of violence towards women, such as in sexual and domestic violence, the coherent belief of gender differences, and other factors.

First, for political status, the laws and systems related to women tended to build a legal equality, but it showed an incomplete equality due to a gap between the laws and reality, the scarcity of women in decision- making positions, and other factors.

Second, for economic status, women’s economic participation has been increasing in general, especially for married women. However, the improvement in economic status can be considered as a kind of optical illusion due to the conversion of women into temporary positions, the double burden from work-life balance, the gender-inequality from work-life balance, the limited occupational activities of women, the scarcity in decision-making positions, and other factors.

Third, as for human rights, various laws and systems have been built to punish abusers and to protect victims by establishing domestic violence, sexual violence, and prostitution as violations of women’s rights and empowerment. This enactment helped the general public recognize violence against women as a crime. However, violence towards women is increasing and the fear of sexual harassment, sexual violence, and physical violence is still prevalent.

As a result, a gender oriented social order, that is to say the gender specialization, is encroaching on modern society. However, the traditional gender standard, including the gender division of labor and gender role segregation, is maintained underneath the surface so that gender equality through the improvement of social status remains in an incomplete state. In the future, the endeavor for the improvement of women’s social status should explain the paradoxical inequality hidden underneath the superficial success. Women’s personal strength, the activities of organizations for the feminist movement, the official political system, and the nation are all needed in order to change the gender division of labor, the unbalanced authority, and the social order. Furthermore, all these elements are in inseparable relationship and we need to pay attention to their roles.

Notes

2 Besides the above, Chamberlayne also proposed a gender reinforcement type that has a purpose of reconfirming the role with the traditional relationship.

3 However, the number of female election winners in local assemblies has been small, even when the number of female members has increased. For metropolitan council, there has been no female election winner ever since the first election of local council in 1995; only 1 out of 230 in 1995, 2 out of 232 in 2002, and 3 out of 230 in 2006 had been elected for local government positions (Korean Women’s Development Institute, 2009).

4 Violence against women was rapidly institutionalized after the enactment of related laws, and its contents consist of increased operation budget for the victims and the extended support system. These fundamentals of system contributed much to support the victims from family violence and sexual violence, and the recognition of crimes of sexual violence and wife battering has spread among the general public ever since the nactment of related laws (Lee, 2008, pp. 24-28).

5 By the way, the relation between the increase of assemblywomen and the process of assembly activities show that the assemblywomen do much more proactive legislative work through cooperation and competition as the ratio of assemblywomen increases (Kim et al., 2009, p. 173).

6 It showed that the wives are barely enjoying leisure activities due to housework, and as per ways to spend leisure time during weekends and holidays, the majority of husbands (34.6%) replied that they spent most time watching TV and video, whereas the majority of wives (31.6%) answered housework (The Financial News, May 19, 2010).

7 The policy of work-life balance is a ‘support policy for men and women workers who are responsible for child support.’ This means the policy is to support the parents by easing them from the family burden of childcare, so that they would not stop working due to childcare and continue their employment, and to support the equality in the family and work by encouraging men’s participation in childcare. It was shown that married women are having difficulties to continue their career and experiencing the limitation of employment opportunity despite the fact that women’s employment has been increasing and the trend of dual income family has become more common. This phenomenon is even more apparent among the families with younger and more children (Hong, 2009, p. 26).

8 For the reinforcement of women’s authority, France is enacting a law which requires 50% women executives in corporations by 2015, and Norway is also implementing a law of gender equality at corporations, yielding a rapid growth of women executives to 44.2% (Chun, 2009, p. 143).

9 The GGI index consists of 4 areas and its background of selection is as followed. First, not only is women’s economic participation an important method to increase the household income, but it also reduces the gap of poverty between men and women. Second, the economic opportunity was selected as a matter related to the quality of women’s economic engagement. Third, the political participation was selected as it can measure the women’s representativeness in the decision-making structure. It also measures how the nation’s priorities are defined. Fourth, the educational achievement was selected as it is a fundamental condition to improve women’s authority in all social aspects. Fifth, health and welfare were selected as they are the subjects related to the basic personal safety despite of different approaches of men and women (Chun, 2009, p. 78).

References

-

Bradley, K., & Khor, D., (1993), Toward an Integration of Theory and Research on the Status of Women, Gender and Society, 7(3), p347-378.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/089124393007003003]

- Chamberlayne, P., (1993), Women and the State: Changes in Roles and Rights in France, West Germany, Italy and Britain, 1970-1990. In J. Lewis (Ed.), Women and Social Policies in Europe, Edward Elgar, New York, p170-193.

- Cho, H., (1996), Gender Equality and Regal System, Ehwa Women’s University Publication, Seoul.

- Cho, Y. S., (2010, October, 5), The Path that Feminist Movement Followed, Retrieved December 17, 2010, from http://news.vop.co.kr/view .

- Chun, K. T., (2009), Plan of Gender Equality Index Management for Reinforcement of National Competitiveness, Korean Women’s Development Institute, Seoul.

- Esping-Andersen, G., (2009), The Incomplete Revolution, Polity Press, Oxford.

- Hong, S. A., (2009), Working Parents and Work-Family Balance in Sweden, the UK and Korea, Korean Women’s Development Institute, Seoul.

- Kim, M. C., (1998), Informatization and the Transformation of Women’s Social Status in Korea, Asian Women, 7, p129-146.

- Kim, W. H., Yang, K. S., & Jung, H. O., (2009), The Research for a Change of Local Council Activities of Men and Women Assembly Members per Increase of Women Members in Local Council, Korean Women’s Development Institute, Seoul.

- Korean Social Policy Institute, (2010, September, 14), Age of 100 Years Old, A Life Course Plan for Korean Women Survey of Women’s Consciousness, Korea Press Foundation Women News.

- Korean Women’s Development Institute, (2009), Gender Statistics in Korea 2009, Korean Women’s Development Institute, Seoul.

- Korean Women’s Development Institute, (2010), Women in Korea, Korean Women’s Development Institute, Seoul.

- Lee, G. S., (1999), Social Status of South and North Korean Women, Kyungsung University Unification Treatises, 15, p7-39.

- Lee, H. J., (2008), Plan for Service Improvement on the Violence Against Women: Based on Support System for Victims of Family and Sexual Violences, Korean Women’s Development Institute, Seoul.

- Lee, J. Y., (2001), Comparison of Korean and Chinese Women’s Social Status, Unpublished master’s thesis, University of Hallym, Chuncheon, Korea.

- National Assembly Research Service Internal Resources, (2010), Retrieved December 17, 2010, from http://www.e-welfare.go.kr.

- Park, H. J., (2010, September, 21), Assessment of Moo-hyun Roh Administration, Qualitative Improvement is a Poor Positive Assessment, Retrieved December 17, 2010, from http://www.cage.org/mboard .

- Sainsbury, D., (1997), Gender, Equality and Welfare State, Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Sohn, D. S., (1989), Women’s Domestic Work and Status of Women, Journal of Women’s Problems Research Institute, 17, p7-25.

- Special Committee on Gender Equality, (1998), 1998-2002 The 1st Master Plan for Women Policy, Presidential Commission on Women’s Affairs, Seoul.

- Statistics Korea, (2009), 2009 Women’s Life by Statistics, Retrieved December 17, 2010, from http://kostat.go.kr.

-

Straus, M. A., Sugarman, D. B., & Giles-Sims, J., (1997), Spanking by parents and

subsequent antisocial behavior of children, Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent

Medicine, 151, p761-767.

[https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170450011002]

- Tarique, M. D., & Sultan, Z. A., (2001), Status of Women in Saarc Countries: A Comparative Analysis in the 10th Conference Volume of Indian Economic Association, Retrieved December 17, 2010, from http://king-Sand.academia.Edu/Dr.M.Tarique/paper/91915 .

- Wu, M. S., (2006), The Changes of Korean Women’s Economic Status and Nation’s Role: Based on Debates of the Nation’s Autonomy from the Feminist Theory of the Nation, Korean Social Science, 40(3), p62-90.

- YTN, (2010, September, 22), Do Not Bear a Child to Work?, Retrieved December 17, 2010, from http://media.daum.net/nms/service/news.