Is Policy Succeeding? Gender differences in national pension in Korea, 1973-20071

This paper examines the effects of the National Pension reforms of 1973, 1988, 1999 and 2007 on gender differences in pensions in the Republic of Korea. Reduction in minimum required insured terms for old age pension, changes in entitlement conditions for the divorced and the widowed, and the introduction of child credit and flat rate basic pension all together make this question important. The study questions whether the gender gap increases or decreases and to what extent it is to do with the changes in policy arrangements. If the change occurs this paper also examines the way in which the men’s and women’s pension entitlements are differentiated under the each reform. This research employs the bases of entitlements as a conceptual tool and methodologically it devises synthetic couples. The findings suggest that the gender differences in pensions decreases, but it is questionable whether it is largely related to the change in the National Pension arrangements. Also, the National Pension is proven to be a weaker protection for low income groups. The extent to which child credits and the changes in conditions attached to the survivor pensions and divided pensions would be residual. Furthermore, the conditions attached to co-receipt of different pension entitlements should be brought into further consideration.

Keywords:

National Pension, gender differences, reforms, simulation, KoreaIntroduction

This paper examines the effects of the National Pension (NP) reforms on gender differences in pensions in the Republic of Korea (hereafter, Korea). Korea has four public pension schemes. The public pension schemes first covered three professional groups: the Military Personnel Pension in 1961; the Government Employees’ Pension in 1963 and the Private School Teachers’ pension in 1975. The NP is the main public pension scheme for the rest of population. The NP provides earnings-related pensions. The revenue required for payment of benefits is funded from contributions paid by insured persons and their employers; the government assumes only a portion of the administrative costs. Since the initial consideration of the policy in 1973, entitlements for women have changed significantly. In 1973, the policy was to be implemented as the National Welfare Pension (NWP), which interestingly contained favourable provisions for female workers. However, its enactment was postponed until 1988 due to the oil crisis. The provisions of the 1988 law excluded the favourable provisions of the 1973 law. After coverage was expanded to employees in firms with five or more regular employees in 1992 and to people in rural areas in 1995, the NP offered coverage to the self-employed in urban areas in 1999. The reform also introduced divided pensions for the divorced and postponement of contributions for women who had given birth. In 2007, the reform changed the rules about providing survivor pensions and divided pensions and introduced child credits. The government also introduced a non-contributory, flat rate, income-based old age basic pension that year.

This research employs the bases of entitlements proposed by Sainsbury (1996) as an analytical tool. The research attempts to move away from the assumption that women are and will be disadvantaged as the policies do not effectively consider the difficulties that women have in building up pension rights. The bases of entitlements enable us to examine in detail the way in which the NP reforms differentiate men and women’s pensions. In regard to methodology, this paper uses the hypothetical simulation model developed by An (2009). The approach will be to create synthetic couples in order to compare the effects of each reform on gender differences in total pensions and to examine differences in the extent to which women’s entitlements as wives, mothers, and workers as well as their need are differentiated in the NP.

This paper argues that the reforms will decrease the gender gaps in pensions, although the extent of the decrease is questionable. The NP offers less protection to low income groups. The extent to which child credits and the changes in conditions attached to the survivor pensions and divided pensions would be small. Furthermore, the conditions attached to co-receipt of different pension entitlements should be brought into further consideration. The following section discusses the merits of bases of entitlements, followed by a discussion on gender relations in the labour market over four decades. It subsequently discusses the methodology, its merits and limitations, and results, and draws conclusions.

Gender Analysis of Pension Policy

Gender difference in pensions has long been on the research agenda in academia. The disadvantaged position of older women has received a fair amount of scholarly attention, especially with regard to its high correlation with poverty. For example, in Britain, several studies of the economic position of older women have concluded that women are significantly disadvantaged in pensions and are more likely to be trapped in poverty than men (Arber & Ginn, 1991; Groves, 1991; in a comparative context, Ginn & Arber, 1992, 1994). According to the Department of Social Security (DSS) in Great Britain, female pensioners and women who live alone are particularly vulnerable to low income. Nearly 62 percent of single female pensioners have an income that relegated them to the bottom two quintiles of the country, with only six percent in the top fifth (DSS, 1997). The final report of the European Observatory on Older People in Europe recognised feminised poverty among the elderly as “one of the most pressing [issues] facing policy makers” (Walker, Arber & Guilema, 1993, p. 46).

The thinking in the gender analyses of the NP policy stemmed from the assumption that the policy adhered to the male breadwinner model, in which married women’s financial security is not the responsibility of the state, but of their husbands. Eligibility for the pension is based on breadwinner status and the principle of maintenance. Most wives’ rights to benefits are derived from their status as dependants. This model suggests that women enter old age with different socio-economic experiences than men, having shorter working lives and lower lifetime wages. Meanwhile, the welfare provision for old age is designed to provide high pensions for long and uninterrupted labor market participation. In her comparative analysis of gender impact of pension reforms both in Great Britain and Korea, An (2005) argued that, in order to enhance women’s pension rights, the Korean government should move away from the traditional male breadwinner assumptions. Um (2003) also argued that, in order to enhance women’s pension rights, individualization is necessary. Shu (2006) pointed out that the influence of Confucianism has made the male breadwinner logic more influential in Korea than in Britain; consequently, Shu proposed a reform to enhance women’s access to the NP as individuals, not as wives.

Although the analyses suggest a lot about the degree to which women are disadvantaged, there is the need exists to move to a wider mechanism. Recent comparative gender studies on the welfare state have found some weaknesses in analyses of the male breadwinner model, including its minimization of the impact of welfare provisions based on men’s and women’s citizenship. Examinations of Swedish policies support Sainsbury’s (1996) argument that citizenship-based provisions have profound defamilializing potential. In addition, Sainsbury (1996) held that the principle of maintenance and the principle of care should be analyzed separately. According to Sainsbury (1996), the weakness of the breadwinner model is its concentration on the husband as the principal beneficiary and the main source of a wife’s social entitlements. The model thus fails to distinguish between women’s entitlements as wives and their entitlements as mothers. When women’s entitlements as wives and mothers are compounded, a fundamental difference in the construction of family benefits is easily missed: whether benefits are tied to the principle of care with the mother as the recipient or to the principle of maintenance, conferring rights upon the father. According to Lewis and Ostner’s (1994) typology of breadwinner status, both the Netherlands and the United Kingdom (UK) are strong male breadwinner states; however, the principle of maintenance underpins Dutch benefits, while family benefits in the UK have entailed recognition of the principle of care. Sainsbury (1996) argues that benefits based on motherhood have the potential to undermine the principle of maintenance, providing a decent standard of living independent of family relationships.

An analysis of how men and women are differentiated in their access to the NP provides effective and significant discussions on the effects of the NP on gender differences. Differentiating the path to welfare, particularly in terms of workers, mothers, wives, and citizens, has merits for gender analysis. Lewis’s (1992) male breadwinner model starts from an inquiry about the way in which the welfare state views women, focusing on only two statuses: either paid worker or dependent wife. The current research analyses how men’s and women’s entitlements as workers have changed over time, including women’s entitlements as dependent wives. Furthermore, it shows how newly made entitlements such as mothers (through child credit) and citizens with need (through the basic pension) could contribute to women’s pension entitlements. As such, this analysis will shed some light on how the Korean welfare state has viewed women in the pension provisions for the last four decades.

Gender Division of Labour: continuities and discontinuities

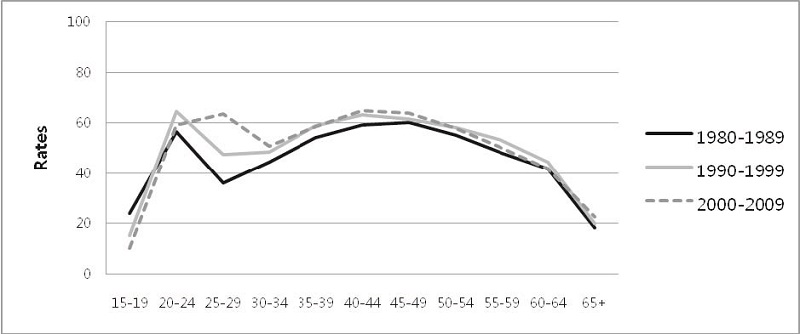

In order to discuss the gender division of labour in Korea, this section looks at gender differences in the labour market in terms of participation rates, employment status, and wages. It also examines the family formations and dissolutions by studying marriage, divorce, and fertility rates. Finally, women’s and men’s time spent on paid and unpaid work is analysed using Korean time use surveys from 1999, 2004, and 2009. Changes in notions of women’s paid work are also examined. During the 1970s and 2000s, men’s participation decreased from 77.5 percent to 74.1 percent while women’s labour market participation increased from 41.3 percent to 49.5 percent during the reference periods2. Figures 1 shows women’s labor market participation rates by age groups. Women’s rates show significant changes. First, between the ages of 20 and 59, the age band with the lowest rates was 25-29 in 1970-1979 and 1980-1989. This shifted to 30-34 in 2000-2009, thereby reflecting a delay in marriage. However, it is important to note that the rates of the 30-34 age group increased from 44.5 percent to 50.9 percent. In addition, the rates of the 25-29 age band rose dramatically, from 36 percent to 63.6 percent. This is also the case for the 35-54 age band. Such changes suggest that neither marriage nor childbearing have a similar negative impact on women’s labor market participation, as compared to the past. It shows that an increasing number of mothers with young children are working.

Women's Labour Market Participations by Age GroupsSource: Author’s calculation based on data from KOSIS

Labour Market Participation by Employment Status and SexNote. Korean labor market classified the workers first as unpaid workers and paid workers. The unpaid workers consist of self-employed employers and unpaid family workers; paid workers consist of regular, temporary, and hourly workers. Unpaid family workers are families of the self-employed, working more than 1/3 of regular working hours without payment. Regular workers are those employed more than one year and receiving payment. Temporary workers are those employed for less than one year and hourly workers are those working on hourly basis. For the 1970s and 1980s, the proportion of regular workers is the same as non hourly workers. The 1970s and 1980s data do not contain proportions for temporary worker and regular workers separately. In addition, the 1970 data does not separate the self-employed from employers.Source: Author’s calculation based on data from KOSIS

Figure 2 shows the labour market participation by employment status and sex. During the four reference periods, the percentage of male paid workers rose from 47.5 percent to 54.5 percent to 64.5percent and finally to 66.1 percent. Similarly, the percentage of female paid workers dramatically increased from 31.4 to 44 to 58.9 percent and finally to 66.4 percent. Between 2000 and 2009, the proportion of female paid workers was higher than that of males by 0.3 percentage points. In addition, the increase of female paid workers mirrored the increase of temporary workers. Between the 1990s and the 2000s, whereas the proportion of regular workers increased by two percentage points, the proportion of temporary workers increased by 5.2 percentage points. Between the reference periods, the proportion of female paid workers increased by 7.5 percent, with 68 percent of the increase accounting for the increase in the number of temporary workers. Despite the dramatic increase in female paid workers, it is important to point out that, of total paid workers, 62.1 percent of male workers were regular workers while only 37.8 percent of female workers were regular workers. In addition, women’s wages were only 43.9 percent of men’s during 1970-1979, which increased to 58.6 percent during 2000-2009. The sex ratio decreased from 67 percent during 1990-1999 to 58.6 percent during 2000-2009; this is perhaps due to the significant increase in the number of female irregular (i.e., temporary and daily) workers.

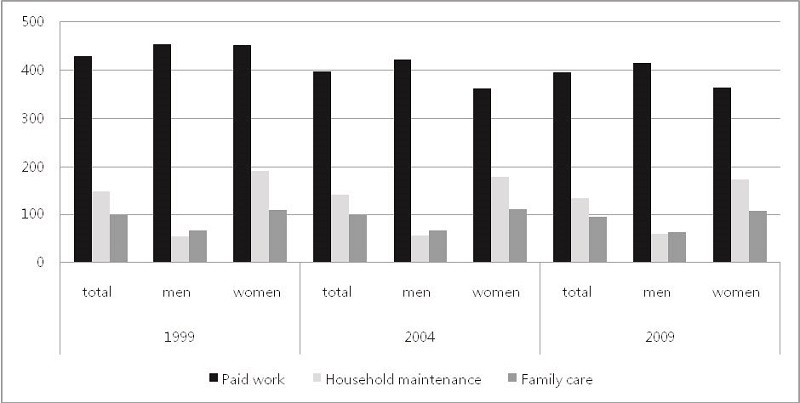

How have the changes in women’s paid employment resulted in gender differences in work and care? Figures 3 and 4 show the amount of time spent on paid work, household, and family care. Figure 3 shows the figures for the population aged 10 and over who actually performed the activities between 1999 and 2009, indicating that the gendered patterns have remained largely intact over time. For both men and women, the time spent on paid work has been reduced, although the decrease is greater for women than for men. Men’s time spent on both household maintenance and family care increased by one minute, which is much less than the more than four hours a day reported by women.

Amount of Time Spent on Paid Work, Household Maintenance and Family Care per DayNote. The figures are for those who actually did the activities.Source: Author’s calculation based on data from KOSIS

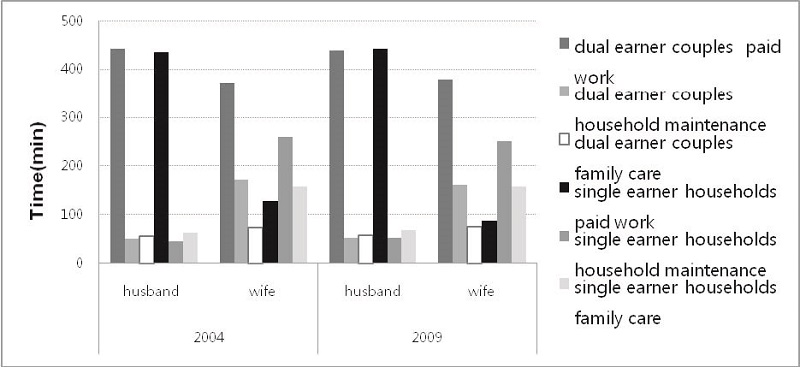

The increase in the number of dual-earner households is related to interesting realities regarding gender relations for work and care. Figure 4 shows the amounts of time spent on paid work, household maintenance, and family by single- and dual-earner households. The husbands in both single- and dual-earner households spent comparatively less time on household maintenance and family care and much more time on paid work than their wives did. The working wives appeared to spend less time on household maintenance and family care than full-time housewives. However, the amount of time spent by the working wives on household maintenance and family care was much more than the time spent by their husbands. In 2009, the husbands spent 109 minutes a day on household maintenance and family care while working wives spent 237 minutes on the same activities.

Amount of Time Spent on Paid Work, Household Maintenance and Family Care by Single and Dual Earner Households per Day (minutes)Note. The figures are for those who actually performed the activities. Paid work includes employed and self-employed work, unpaid work in a family business, unpaid work on a family/ fishery/forest, unpaid work for self-consumption, job search, purchase of goods related to job and other employment activities. Household maintenance includes activities such as food preparation, clothes care, cleaning and arrangement, house upkeep, purchasing goods for household care, and household management. Family care includes activities such as care of preschool child, care of school-age child, care of spouse, care of parents and care of other members of the family.Source: Author’s calculation based on data from KOSIS

According to the National Statistics Office (NSO), in total, 6.7 percent of the respondents agreed that all of the household maintenance should be done by wives, 59.8 percent agreed that wives should do the most household work with some help from husbands, and 32.4 percent thought the housework should be fairly shared between husband and wife. The agreement for the fair sharing was made more emphatically by women than by men. Interestingly, 64.7 percent of respondents aged 15-19 thought that the household work should shared equally by husband and wife. This is a striking figure when compared to what the older generations think: only 20.3 percent of the aged 60 and over participants agreed that husbands and wives should share the household work.

In sum, over the decades, women’s positions in the labor market have improved. However, the improvements in the female labor market participation have largely occurred through the increase of irregular workers. Furthermore, despite the increase, gender relations within family have not changed. Mothers are still conducting most unpaid care work. For the NP reforms, it is questionable how much good it would do to enhance pension rights based on the work of people who work on an irregular basis. A question also exists regarding how women’s burden for family care is taken care of by the NP. The increase in the number of working wives implies that more women would have different pension entitlements based on their own employment experiences and as dependent wives. Thus, it is worth asking how the NP reforms deal with the emergence of different entitlements for women.

Changes in the Bases of Entitlements

This section summarises the programmatic features of NP reforms between 1973 and 2007. Table 1 shows the structure, contribution rates, and replacement rates. The year 2007 marked the advent of a two-pillar system, with the introduction of a basic old age pension in addition to pre-existing earnings-related pensions. Contribution rates rose from three percent in 1988 to nine percent in 1999, remaining unchanged in 2007. Replacement rates fell from 70 percent in 1986 to 60 percent in 1998 and 50 percent in 2007.

Table 2 summarises the changes of the NP in terms of the bases of entitlements. In the 1973 NWP, working women received favourable treatment. Women were entitled to full old age pensions at 55 and a minimum of two years of insured terms. As dependent wives, women were eligible for supplementary pensions and survivor pensions; there were no measures for women as mothers and citizens. In the 1988 NP, these favourable terms for female workers were removed. As wives, they were eligible for supplementary pensions and survivor pensions. The amounts of survivor pensions were determined by the insured terms of the deceased and were suspended at remarriage. No measures were included for women as mothers and citizens. In the 1999 NP, as workers, women could benefit from the minimum insured terms being reduced to 10 years from 15 years. As wives, in addition to the survivor pensions and supplementary pensions, the measure of divided pensions for divorcees was introduced for those whose marriage lasted more than five years. Women could also postpone the payment of contributions if they stopped working to bear and raise children.

In 2007, mothers with more than two children could benefit from child credits. The second child added 12 months and the third child added 18 months to the contribution years of the mother, up to 50 months. In addition, women’s access to the NP as wives was enhanced. Previously, when two different entitlements occurred (e.g., one derived from their own contribution and one derived from their dependent status), the survivors had to choose one. The 2007 reform provided 20 percent of the survivor pensions when the survivors selected their own pensions. Furthermore, divorcees were entitled not only to their own pensions, but also to the divided pensions of their spouses. Finally, the basic pension, which is a need-based provision, was introduced.

Methodology

A common way of addressing gender differences is to use longitudinal panel data, which track an individual’s employment, family history, and state pensions. One longitudinal data source is the Korean Labour and Income Panel Survey (KLIP); however, the first survey was completed in 1998, so the information is dated. In such a case, one might consider creating a longitudinal database known as a dynamic cohort micro-simulation model (Evans & Falkingham, 1997; Falkingham & Lessof, 1992; Nelissen, 1994), which ages each individual in a sample to build up a synthetic longitudinal database describing sample members’ lifetimes. In order to generate the micro-simulation model, it is necessary to have accurate and complete data on gender, education, marriage, childbirth, employment, time of retirement, and mortality. However, not all data are accessible, making the development of a micro-simulation model difficult. Scholars often find that, even if a source of individuals’ complete life histories did exist, such a source would still not address certain issues. For example, Rake, Davis & Alami (2000) argue that, by its nature, such a source would be retrospective, and the data on the early years of people in their sixties and above would relate to the circumstances of the previous 30 or more years. This aspect of longitudinal source would be problematic if the purpose of analysis is prospective rather than retrospective (e.g., to forecast income prospects of today’s younger generations and not look backwards at the history of older generations).

As an alternative, this thesis employs a hypothetical simulation model to address the gender effect of the NPS. An obvious limitation of the hypothetical simulation model is that it is not possible to generalize the results. However, the hypothetical simulation model has an advantage in that the operations of particular elements of policies can be examined in detail, allowing the researcher to examine the link between national policy arrangements and individual outcomes more fully (Rake et al., 2000).

The development of the simulation model consists of three steps. The first specifies the synthetic cases while the second step predicts the likelihood of being in the labor market and the wages. The last step, based on the predictions on the contribution periods and wages, is to calculate the predicted amount of pensions of each synthetic case. The simulation model runs under the unrealistic assumption that the reform remains constant for the synthetic couples’ entire life period.

Step 1: Specification of Synthetic Cases

As a first step, the characteristics of the synthetic couples (e.g., education, childbirth, marriage, and time of death) are based on cross-sectional data from NSO. As benchmark cases, three synthetic couples are devised, differentiated by educational qualifications. For comparisons for each educational qualification level, cases with two children are devised. Those with no more than a middle school education are regarded as “Low,” those with high school education and two-year college education are “Middle,” and those with university level and above are “High.” It is assumed that the couple has same educational qualifications; husbands are three years older than the wives. The marriage is assumed to be a lifetime contract, although cases are devised in which divorce occurs in order to examine the impact of the divided pensions. It is assumed that the more highly educated the wife is, the older she is when she gives birth to her first child. It is further assumed that all mothers have their first child two years after marriage and subsequent children at two-year intervals. Women tend to leave the labor market due to child-bearing and -rearing responsibilities and are thus assumed to have a break in their career. For the 1973 analysis, mothers are assumed to be unemployed between the birth of their first child until the age of 54. For 1988, 1999, and 2007 analyses, mothers are assumed to be unemployed for 15 years after the birth of their first child. The synthetic male cases are assumed to live until the age of 75, while the synthetic females to 82. The details of the synthetic couples are depicted in Table 3.

Step 2: Predictions on Labour Market Participation and Wages

Cross-sectional data would be useful to predict the cases’ lifetime employment history and wages. For the 2007 pension reform analysis, the Economically Active Population Survey (EAPS) provides data on employment status and wages. However, neither the 1988 nor 1999 EAPS contain information on wages. In addition, the 1973 EAPS is not available as a micro data set. Thus, for the 1973 NWP, it is assumed that both husbands and wives with no children have a lifetime employment history as full-time regular workers. For wages, average wages are used for occupations. It is further assumed that wives with two children quit their jobs as irregular workers before the birth of the first child, receiving one third of average wages of full-time workers, and remained unemployed until the age of 54. For 1988 and 1999 NP analysis, the employment history can be predicted using the EAPS dataset, whereas for wages husbands are assumed to be lifelong regular workers, earning the average wage for their occupation. For women, the average amount of wages of the occupation while they are regular workers is used; one third of the average wages is used when they are irregularly employed. For the 2007 NP analysis, cases’ employment history and wages are predicted using EAPS.

Using multinomial logistic model, the outcomes of employment are predicted for “not employed,” “employed regular,” or “employed irregular.” If the probability of employment is larger than 0.5, the case is counted as “employed.” Among the employed, if the possibility of being employed on a regular basis is larger than 0.5, the individual is counted as a regular worker; otherwise, he or she is counted as an irregular worker. Regression outputs (see Appendix A) indicate that independent variables such as sex, marital status, age, occupation, and education have a statistically significant impact on employment status and wage. Predicted insured years and wages are given in Appendix B.

Step 3: Calculation of Predicted Pensions

The expected pension amounts of each case of the devised couples are calculated according to the information provided in Tables 2 and 4.

A few caveats apply for the analysis. First, this research assumes that each synthetic case makes contributions while employed while the respective employers also pay contributions on behalf of employees. Second, the average monthly wage of all insured needs to be known, which is A in the calculation formula. In the case of 1973, these data are absent. Instead, this research uses the average wage of paid workers in 1973. Third, the husband’s pension includes the supplementary pension, which it only includes as a spousal supplementary. Fourth, the provision of the flat rate basic pension is income, not wages. However, for simplicity, the current study considers the pension amount as the income at age 65 to be applied in the provision of the basic pension. Fifth, those whose insured terms are shorter than 10 years are entitled to the lump-sum benefits. In calculating this, interest rates should be applied. However, in the interest of simplicity, lump-sum benefits are divided into a monthly basis. Finally, prices are constant; no allowance is made for either inflation or indexation.

Results and Discussion

Table 5 shows the predicted monthly pension output of the cases under the 1973 rule. Significant gender differences in pensions are evident. Despite working wives’ long insured years in the DE households, Mrs. Low’s pension is 73 percent of her husband’s while Mrs. Mid’s is 75 percent and Mrs. High’s is 62 percent. Second, marriage and childbirth may indicate a 45 percent reduction in pension for Mrs. Low and Mrs. Mid and a 40 percent reduction for Mrs. High in the MB. Third, the earlier entitlement age for women (i.e., 55) increases women’s pensions compared to when the age is 60. In the MB, the five years increase the pensions of Mrs. Low, Mrs. Mid, and Mrs. High by 24 percent; in the DE couples, increase was 23 percent for Mrs. Low and Mrs. High and 19 percent for Mrs. Mid. This result has much smaller gender differences in total pensions. In addition, if we look at Mr. and Mrs. Low in both dual-earner and male-breadwinner households after the husband’s death, the pension of Mrs. Low in the male-breadwinner couple is higher than that of Mrs. Low in the dual-earner household. This indicates that the NWPS has strong familial dependency: A worker’s life is valued less than that of a housewife.

In summary, women can be entitled to the NWPS as both workers and wives. The analysis shows that, for Mrs. Low, working pensions account for 73 percent of her lifetime total pensions while they account for 74 percent for Mrs. Mid and 69 percent for Mrs. High. This is largely due to the early entitlement age for women. The remaining total pensions are entitled as dependent wives.

Table 6 shows the predicted monthly pension outputs under the 1988 rule. First, despite the long insured years of the working wives in the DE, Mrs. Low’s pension accounts for 82 percent of her husband’s; for Mrs. Mid it is 84 percent and for Mrs. High it is 61 percent. In the MB households, no wives are entitled to old age pensions as their insured years are shorter than the required minimum (i.e., 15 years). Therefore, they receive lump sum benefits at the age of 60. If we calculate the amount on a monthly basis between 60 and 75, the pension entitlements of the wives are only seven percent of their husbands’ entitlements for Mrs. Low, 8 percent for Mrs. Mid, and 10 percent for Mrs. High. In addition, marriage and childbirth may indicate a 92 percent reduction in pension for Mrs. Low and an 88 percent reduction for Mrs. Mid and Mrs. High. Third, after the husband’s death, the pension of Mrs. Mid in the MB couple is higher than that of Mrs. Mid in the DE couple, indicating that the 1988 rule that did not allow the co-receipt of different entitlements reinforces the familial dependency that values a worker’s life less than that of a housewife.

In summary, women can be entitled to the NPS as both workers and wives. The analysis shows that, for Mrs. Low in the MB, pensions as workers account for 15 percent of their total lifetime pensions; they account for 18 percent for Mrs. Mid and 25 percent for Mrs. High. The rest of the total pensions are entitled as dependent wives. Compared to 1973 NWPS, the significant gender differences in pensions as workers in 1988 compared to 1973 rule are due, firstly, to the removal of the five earlier entitlements, changing the minimum required insured years from 10 to 15 years.

Table 7 shows the results of the predicted monthly pensions under the 1999 rule. First, despite long insured years of working wives in the DE, Mrs. Mid is entitled to 67 percent of her husband’s pension and earns 66 percent of Mrs. High’s. Interestingly, despite the higher wages, the NP gives a better value for longer insured years if we look at Mr. and Mrs. Low in the DE. The gap is much smaller compared to the results under the 1988 rule. In addition, the gender gap in pensions among the MBs is also smaller than under the 1988 rule. Mrs. Low’s pensions account for 53 percent, while Mrs. Mid’s is 26 percent and Mrs. High’s is 40 percent. Second, under the 1999 rule, having two children might mean a 49 percent reduction for Mrs. Low, a 62 percent reduction for Mrs. Mid, and a 40 percent reduction for Mrs. High in the MB. This is much better than the results under the 1988 rule. All these reductions in pension gaps may be partly due to wives’ and mothers’ improved participation in the labour market. It is important to note that the policy change that reduced the minimum required insured years for old age pension from 15 years to 10 contributed to the improvements, as shown in the example of Mrs. Mid in the MB. After her husband’s death, Mrs. High in the DE needed to select one of her individual pensions and the derived pensions as a survivor. As 60 percent of the deceased old age pension is higher than her own pension entitlements, she chose the survivor pension. In addition, the widows in the MB should give up their own pension entitlements. As such, this means wives’ lives as independent workers do not help them after their husbands’ death.

In summary, women can be entitled to the NP under the 1999 rule as both workers and wives. The analysis show that pensions as workers account for 69 percent of for Mrs. Low’s lifetime total pensions, 44 percent for Mrs. Mid, and 58 percent for Mrs. High in the MB. The remaining total pensions are entitled as dependent wives. Compared to the 1988 NP, women’s entitlements as workers increased dramatically because of the reduced minimum insured years for old age pension and the improvements in labour market participation.

Table 8 shows the results of predicted monthly pensions under the 2007 rule. First, in the DE, Mrs. Low’s pension accounts for 86 percent of her husbands, whereas for Mrs. Mid it is 72 percent and for Mrs. High it is 89 percent. Second, the child credit improves the wives’ pensions in the MB by seven percent, six percent, and five percent for Mrs. Low, Mrs. Mid, and Mrs. High, respectively. Third, the 2007 rule allows for co-receipt of different entitlements only when it involves the survivor’s pension. If the survivor chooses his or her own pension entitlements, the NP provides 20 percent of the survivor pensions. This results in an increase of the wives in the DE by six to seven percent. However, the wives in the MB do not enjoy this policy change as their survivor pension is higher than their own pension entitlements. This means that their life in the labor market does not support the women after the death of their husbands. Consequently, if we look at Mrs. Low in the MB couple, her pension after her husband’s death is less than 400,000 won, which means she can be entitled to the flat rate basic pension of 80,000 won per month. This gives her 422,319 won. The flat rate basic pension introduced in 2007 increases the wife’s pension by seven percent, which results in her income being above the minimum cost of living (372,978 won per month). Considering that the flat rate basic pension is means tested, it conveys a stigma: If the change in the rule of the survivor pension is not “optional,” the wife should not be a recipient of a means-tested benefit.

In summary, the 2007 reform diversifies women’s entitlements. The lifetime working wives in the DE have additional entitlements (e.g., six to seven percent) as wives. The wives in the MB are very diverse. In the case of Mrs. Low, compared to the 1999 outcomes, her entitlements as a worker dropped from 69 percent to 62 percent. Entitlements as wives also fell from 31 percent to 27 percent. In addition, mothers’ entitlements account for four percent while entitlements based on need account for six percent. In the case of Mrs. Mid, entitlements as workers rose from 44 percent to 62 percent whereas entitlements as wives fell from 56 percent to 34 percent. The remaining 4 percent are mothers’ entitlements. Finally, in the case of Mrs. High, entitlements as workers increased from 58 percent to 66 percent while entitlements as wives decreased from 42 percent to 31 percent. The remaining three percent are entitlements as a mother. All cases saw a reduction in wives’ pension entitlements.

Overall, based on a comparison of 1973, 1988, 1999, and 2007 pension rules, gender differneces in pension have decreased. For example, Mrs. Mid’s pension in DE as a portion of Mr. Mid’s pension increased from 61 percent under the 1988 rule to 67 percent under the 1999 rule and to 72 percent under the 2007 rule. Nonetheless, it is questionable whether these results suggest that the NP is becoming individualised and taking account of women’s still disadvanatgaed positions in the labour market. Figure 5 shows total pensions according to different proportions of entitlements. No change occurred between the 1999 rule and 2007 rule for old age pension entitltments. However, Mrs. Mid’s pension as worker increased from 44 percent to 62 percent and Mrs. High’s pension from 58 percent to 66 percent. This implies that women’s increased share as a worker in their pension has nothing to do with the policy change. Rather, it is related to the female’s increased labour market participations. In addition, if we look at Mrs. Low in DE, her pension as a worker reduced from 69 percent to 62 percent. This might suggest that the NP reforms do not effectively take into account those with an unstable job status. With the introduction of the basic pension, they are pushed to experience social stigma. In addition, policy such as child credits or the changes in entitlement conditions for divorced and widowed women would increase their pension as dependents. Nonetheless, it is worth noting that 26.7 percent of divorced couples lived together less than five years, indicating that a great number of divorced women would not benefit from the policy. In addition, the Korean fertility rate has been on average 1.2 in the 2000s. As such, it is questionable how many mothers would actually benefit from the policy. Futhermore, as demonstrated in the case of Mrs. Low in the MB under the 2007 rule, the conditions attached to the co-receipt of different pension entitlements needs further consideration.

Conclusion

This paper has examined gender differences in pensions under the 1973, 1988, 1999, and 2007 reforms in Korea. Conceptually, this research has employed the bases of entitlements; methodologically, it has developed a hypothetical simulation model. It has revealed that the gender differences in pensions are decreasing. In addition, it also confirmed the finding (An, 2009) that women’s access to the NP has diversified. However, it is not clear whether women’s enhanced pension rights are a result of the policy. Comparing the outcomes of the 1998 and 2007 rules, it is appropriate to conclude that the decreasing gender gap has to do with women’s increased labour market participation. In addition, those with low qualifications would have fewer pension entitlments under the 2007 rule than the 1999 rule. This might indicate that the NP has become a weaker protection for those with unstable job status. The fact that, that in 2007, nearly 63 of female paid workers were irregular workers has important policy implications. The conditions attached to the divided pensions and survivior pensions should to some extent enhance women’s pensions. Yet it is questionable how many divorced women would actually benefit from the policy. The introduction of the child credit is also welcomed, but the extent to which it would enhance women’s pensions is small; moreover, it is questionable how many women would actually benefit from it.

As the Korean society is experiencing changes in gender relations, the results of this study can offer possible suggestions for policy reforms. Firstly, to become a robust protection measure for low income groups, the amount of basic pension needs to be a non-income tested benefit. Secondly, in order to prevent the elderly (after the spouse’s death) from being trapped in poverty, the full amount of the survivor’s pension need to be paid. Thridly, the way in which the policy compensates for the time that women take for child-bearing needs to be expanded and other ways of compensation need to be adopted. Finally, policy makers need to consider how the changes in the rule for benefit calculation can influence low income groups. Although it is not evident in terms of share of unpaid care work within family, it is evident in the labour market. In conclusion, despite the seemingly considerable changes, the NP still lags behind the realities that the Korean society is experiencing from a gender perspective.

Notes

2 Author’s calculation based on statistical Information Service, KOSIS (http://kosis.kr/nsportal/index/index.jsp?sso=ok).

References

- An, M. Y., (2005), Aging and Income Inequality in South Korea: Impact of Recent Pension Reforms, Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Oxford, Oxford.

-

An, M. Y., (2009), Gender Impact of Pension Reforms in Korea, International Social Security Review, 62(2), p77-99.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-246X.2009.01330.x]

- Arber, S., & Ginn, J., (1991), Gender and Later Life: a Sociological Analysis of Resources and Constraints, Sage Publication, London.

- Department of Social Security, (1997), Pensioner’s Income Series 1995/6, Department of Social Security, London.

- Evans, M., & Falkingham, J., (1997), Minimum Pensions and Safety Net in Old Age: A Comparative Analysis, STICERD, London.

- Falkingham, J., & Lessof, C., (1992), Playing God: or LIFEMOD - the Construction of a Dynamic Microsimulation Model. In R. Hancocok and H. Sutherland (Eds.), Microsimulaiton Models for Public Policy Analysis: New Frontiers, STICERD, LSE, London, p5-32.

- Ginn, J., & Arber, S., (1992), Towards Women’s Independence: Pension Systems in Three Contrasting European welfare states, Journal of European Social Policy, 2(4), p255-277.

- Ginn, J., & Arber, S., (1994), Gender and Pensions in Europe: Current Trends in Women Pension Acquisition. In P. Brown and R. Crompton (Eds.), Economic Restructuring and Social Exclusion, UCL Press, London, p58-85.

- Groves, D., (1991), Women and Financial Provision in Old Age. In M. Maclean and D. Groves (Eds.), Women’s Issues in Social Policy, Routledge, London, p38-60.

- Korean Statistical Information Service, KOSIS, http://kosis.kr/nsportal/index/index.jsp?sso=ok.

-

Lewis, J., (1992), Gender and the Developments of Welfare Regimes, Journal of European Social Policy, 2(3), p159-73.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/095892879200200301]

- Lewis, J., & Ostner, I., (1994), Gender and the Evolution of European Social Policies, Centre for Social Policy Research Working Paper 4, University of Bremen.

- National Pension Service, (2007), Kookmin Tong-gae Yonbo [Yearbook of National Pensions], National Pension Corporation.

- Nelissen, J., (1994), Income Distribution and Social Security: an Application of Microsimulation, Chapman and Hall, London.

- Rake, K., Davis, H., & Alami, R., (2000), Women’s Incomes over the Lifetime: a Report to the Women’s Unit, The Stationary Office, London.

- Sainsbury, D., (1996), Gender, Equality and Welfare States, the Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, Cambridge.

- Shu, D. H., (2006), Jeongchak Deasang EuroSeo Yeosung Gaenum Gwa Yeongeum Jeungchak Banghyang: Gaein Jueui Danyei Model Gwan-gum Easu [Women in social policy and national policy reforms: from an individualist perspective], Korean Journal of Policy, 15(2), p37-54.

- Um, G-S., (2003), Europ Bokhi Chaegeeui Gendde Hyowga Bunsucke Gichohan Chineuocungjuck Hankook Yeongeungedoeui Jogun [A study on women friendly pension policy: lessons from gender impact of European welfare states], U-roup Study, 18, p331-362.

- Walker, A., Arlber, J., & Guillemard, A-M., (1993), Older People in the EU: Social and Economic Policies- the 1993 report of the European Observatory, Commission of the EC, Brussels.

Appendix

Appendix A

Appendix B

Biographical Note: The author is working at Kookmin University as assistant professor in the School of Public Administration and Public Policy. Before that, she worked as an assistant professor at Handong Global Univ. She finished her Master degree at King’s College London majoring in social gerontology and got Doctor of Philosophy in social policy from the University of Oxford. Her research areas include gender and social policy, ageing and social policy and comparative social policy (welfare state), East Asian welfare states, social welfare in developing countries, and simulation modeling.Her recent publications and project include

An, M. Y. (2010). Republic of Korea: Analysis of Time Use Survey on Work and Care, In D. Budlender. (Eds). Time Use Studies and Unpaid Care Work. (pp. 118-141). Routledge/UNRISD.

An, M. Y. (2009). Gender Impact of Pension Reforms in Korea. International Social Security Review, 62(2): 77-99.

An, M. Y. (2008). Time use and gender inequality in Korea: differences in paid, unpaid and non-productive activities, Asian Women, 24(3): 1-22. She can be reached at myan@kookmin.ac.kr.