Applicant Screening Practices at Korean Firms

Most Korean employers screen job applicants’ personal backgrounds extensively. Because this screening includes applicants’ protected characteristics including gender, and is not directly related to job requirements, the practice may lead to discrimination and inefficiency in recruitment. This study surveys firms’ screening practices, their aims, and their rationalization vis-à-vis discrimination laws. Interviews with personnel officers of fifteen firms reveal that employers vary in their familiarity with discrimination laws, in the importance they attribute to job application forms, in the frequency with which they update them, and in their justification for intrusive questions on application forms. Employers familiar with discrimination laws ask fewer personal questions, and downplay the importance of personal questions in recruitment. Frequency of updating of application forms reflects inversely the inertia in the firms’ responding to market conditions and laws. Firms asking more personal questions employ fewer women, but appear no more prosperous or successful at selecting dedicated workers. Human resource departments should calibrate their screening practices more carefully and frequently, to align them with their underlying objectives and with social aims. Regulators should create an environment conducive to these efforts.

Keywords:

Recruiting practices, statistical discrimination, profiling, job application forms, Korea JEL Classification: J7, J23Introduction

Most Korean employers seek extensive personal background information that appears unrelated directly to job requirements. Firms’ application forms inquire about applicants’ appearance, family plans and marital status, health, family background, religion, birthplace, finances, and other personal characteristics (Hlasny, 2009). Applicants’ gender and age are surveyed through applicants’ national registration numbers and photographs. Since employers use this information to systematically screen out workers, and since this information tends to be correlated with workers’ membership in protected groups – such as women, the handicapped and other recognized disadvantaged groups – such screening practices are typically considered inappropriate or are downright banned, and their prevalence is an important research topic.

This study therefore aims to investigate employers’ screening practices, their awareness and views of equal opportunity legislation, and the motivation and consequences of their practices. The method used was to interview human resource (HR) officers at fifteen Korean firms. The interviews aimed at understanding employers’ rationale for asking personal questions on application forms, and their justification of the practices vis-à-vis equal employment opportunity laws protecting women and the elderly. We juxtapose officers’ interview responses with their firms’ observed screening practices and economic circumstances to identify the effects of the firms’ conditions on their recruiting practices and the views of their officers. Lastly, we review the consequences of the observed screening practices for firms’ performance and gender composition of their workforce.

The study is organized as follows. The next subsection outlines the employers’ problems with respect to the screening of job applicants and reviews Korean regulations pertaining to recruitment. The following subsection surveys the relevant literature. Section II describes our empirical method and data. Section III presents the main findings and concludes.

Firms’ Problem in Applicant Screening

Employers traditionally inquire about qualities of applicants that have bearing on applicants’ expected job performance or dedication (Phelps, 1972; Light & Ureta, 1992; Cole et al. 2003). These depend on applicants’ cognitive as well as noncognitive skills (Heckman et al. 2006; Borghans et al. 2008). Noncognitive skills are particularly difficult for employers to assess. Some are unquantifiable, unlikely to be reported honestly, or even unknown to the applicants themselves (Barrick et al. 2001; Moy & Lam, 2004). Screening of applicants’ personal characteristics allows employers to infer applicants’ type more precisely. The extent of screening depends on how informative the surveyed characteristics are about applicants’ skills, and on composition of firms’ applicant pools, job skill requirements, duration of employment, and compensation structure (Hlasny, 2014).

In addition to the economic motivation for applicant screening, we may be concerned about its propriety vis-à-vis equal opportunity laws or norms. There are various standards of appropriateness for factors used in the screening of applicants (Arvey & Renz, 1992; Gilliland, 1993; Truxillo et al. 2004). Legality of recruiting practices and of the collected information is the minimal benchmark. Procedural justice would necessitate that recruiting practices be objective, consistent and not susceptible to personal biases, and done by multiple decision-makers who are professionals (Gilliland, 1995). Content-fairness would require that the applicants’ characteristics surveyed be legal, merit-based (in the power of applicants to affect), job-related, non-invasive to applicants’ privacy, and difficult to falsify or distort. Finally, outcome-fairness would require that the recruiting practices impact all protected groups of applicants similarly to the mainstream group, resulting in similar selection rates.

The aim of this study is not to assert that Korean employers’ screening of personal characteristics is inappropriate or discriminatory, but to merely identify patterns in employers’ use of personal information, match it to firms’ observable features, and report employers’ own justifications. Nevertheless, a brief review of the legality of screening questions is warranted.

All personal questions evaluated in this study are inappropriate under one or more standards of fairness. Their content is not merit-based or job-related, is invasive to applicants’ privacy, and requires subjective evaluation by HR officers or employers untrained in HR management. Moreover, applicants may lie on questions about their beliefs, habits, and backgrounds. Perhaps most importantly, when employers act on the collected information, these personal questions incidentally affect selection rates among different groups of applicants. The disadvantaged category may include even protected groups of workers, and so the relevant form of screening may be in direct violation of equal opportunity laws, which are typically concerned with outcome fairness. Under the current legislation and adopted labor treaties, Korean employers are prohibited from considering factors unrelated directly to performance in their treatment of workers. The Act on Equal Employment and Support for Work-Family Reconciliation, Section 2(1), defines discrimination as any “unfair measures by employers in the process of personnel recruitment and in the establishment of working conditions on the basis of gender, pregnancy, marriage or family status.” The Ministry of Employment and Labor (MOEL) and the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) have attempted to curb firms’ screening practices. The MOEL (2007) put forth guidelines for appropriate recruiting practices, aiming to ensure equal opportunity at the initial stage of recruiting (referred to as the documents stage). The NHRC (2003b) analyzed application forms of 100 Korean employers who hired over fifty fulltime employees during 2002, and recommended that employers voluntarily remove personal questions that are not directly related to job performance.

Existing Understanding of Firms’ Problem in Recruiting

The existing studies have, for the most part, been limited to identifying discrimination in employment, and policy evaluation. They have focused on measuring the outcomes of recruitment rather than on understanding the search process itself. Surveys of employers’ job advertisements and application forms have been conducted in the United States (Jolly & Frierson, 1989), Canada (Saunders et al., 1992), Australia (Bennington & Wein, 2000), New Zealand (S. Harcourt & M. Harcourt, 2002; Harcourt et al., 2004; Harcourt et al., 2005a, 2005b), and China (Kuhn & Shen, 2009, 2013; Hlasny & Jiang, 2012; Hlasny, 2013). A common conclusion of these studies is that a substantial number of employers ask applicants about their illnesses and handicaps, and about their dependents, in violation of relevant laws and norms protecting vulnerable groups such as women and the elderly. The count of personal factors screened by various employers is surprisingly similar across Western and East Asian countries (Wallace et al. 2002; Hlasny, 2009).

In Korea, Park (1990), Lee (1994) and Lee et al. (2001) surveyed employers about their criteria in hiring and motivation for the criteria, with greatest focus placed on differences in hiring criteria by applicants’ gender. Hlasny (2011, 2012) analyzed application forms and recruiting criteria of large samples of firms, and inferred statistically the economic rationales for asking various personal questions. Regarding appropriateness of screening methods, Truxillo et al. (2004) reviewed various measures of selection fairness, and their implications for workers’ and firms’ outcomes. Studies surveyed by them indicated that recruiting practices do not affect workers’ performance on the job, and thus firms’ outcomes.

Method

To investigate employers’ recruiting practices and their own justifications of them, we interviewed HR officers of fifteen for-profit employers. The firms were selected among the list of the largest firms in Korea, headquartered in Seoul or in Gyeonggi province, who conducted recruiting events in Seoul at the time of our research. Admittedly, this “convenience sampling” raises a concern over the representativeness of our sample. Firms’ participation may be correlated with their recruiting practices, beliefs, or attitudes. If this is the case, the responses reported in this study may be unreliable estimates of the conduct and views in the population of all Korean firms. Section III, however, finds that the sample appears quite representative in terms of the extent of applicant screening, providing validation to our analysis.

The interviewed firms are all external auditing corporations with formal HR departments, with ₩0.1-40bil. in annual sales, employing between 400 and 31,000 workers. Jointly, they account for 0.02% of Korea’s gross domestic product (₩173bil. out of ₩840tril.), and 0.06% of national private-sector workforce (126,000 out of 22 mil.). They are headquartered in Seoul (10 firms) or in Gyeonggi province (5 firms).1 Their main industrial classifications are finance (5 firms), manufacturing (4 firms), IT service (2 firms), sales (1 firm), media (1 firm), management consultancy (1 firm), and public utility (1 firm).

Our interviewees held various positions in HR departments of their firms, ranging from a clerk to an executive director, and they were all knowledgeable of the recruiting practices at their firms. Twelve of the fifteen interviewed HR officers were familiar with the guidelines set forth by the National Human Rights Commission, the Labor Standards Act and other acts that ban the consideration of applicants’ gender, age and other personal background in employment decisions (collectively referred to as discrimination laws). Twelve interviewees were male and three female.

The interviews were conducted during April-July 2011, using the same consistent interview method and set of questions, and using questions suggested in previous surveys. The interviews were conducted in person to ensure high rate of completion and accuracy of responses, at the expense of sample size. Inquiry was funneled from general background information about the officers, the firm’s organization structure, the recruiting process and the system of revising it over time, the role of application forms, and the officer’s view regarding the purpose and appropriateness of personal questions. Our detailed inquiry about individual personal questions, their appropriateness, and the officers’ familiarity with discrimination laws was deferred to the end of the interviews to establish trust and prevent attrition.

We asked the interviewees specifically about 1) the importance of an application form in the hiring process using a 5-point Likert scale, 2) the importance of applicants’ appearance and their photograph in hiring, 3) characteristics of an ideal job candidate, 4) reason for asking each personal question, 5) the department or person responsible for creating or revising the application form, 6) frequency of updating of application forms, 7) fraction of applicants selected from the documents stage for standardized tests or personal interviews, 8) gender ratio among the firm’s workforce, 9) interviewees’ familiarity with discrimination laws, and 10) interviewees’ own thoughts regarding the prohibition of personal questions on application forms. Likert scale measures of importance were anchored as follows: 1-not important at all; 3-of medium importance; 5-very important. The transcript of our interviews is available on request. Tables 1 and 2 report interviewees’ detailed responses.

Interviewees were instructed to provide their candid opinions regarding the justification of recruiting practices at their firms. They were promised protection of their own identity as well as that of their firms. Still, several interviewees refused to respond to selected queries, and some replied in a formal fashion that did not appear candid. Most responses clearly exhibited a bias in the direction of social desirability: familiarity with the concerned laws, and legality and appropriateness of personal questions asked on application forms. This study, however, does not concern itself with the honesty of their beliefs, but rather with their stated viewpoints. Information from the interviews is analyzed qualitatively, noting patterns in the data and relationships among responses to various questions, content of application forms, and employers’ characteristics. Quantitative tests of patterns in the data are performed, recognizing the small sample size and the potential subjectivity and imprecision in interview responses.

Findings

Table 2 reports on the recruiting process used by each of the interviewed firms, and on the personal questions asked on their application forms. Nine out of the fifteen firms (or 60%) ask about family background including each family member’s name, age, education level, job, employer’s name, job position, and address. Three firms (20%) ask about birthplace; four (26.7%) about marital status; one (6.7%) about financial status; two (13.3%) about dwelling type or home ownership; one (6.7%) about method of financing one’s education; four (26.7%) about physical appearance; six (40%) about the reason for military exemption; and three (20%) about religion. Five firms do not ask about health but require a medical check-up. This prevalence of personal questions is similar to that reported by the NHRC (2003b) or by Hlasny (2009).2 For example, Hlasny (2009) reports that prevalence of questions about family background is 57.3% in a large representative sample of 389 firms in year 2008, while it is 60% in our small sample. Prevalence rates for questions about financial status (11% vs. 6.7%), home ownership (15.4% vs. 13.3%), and marital status (30.3% vs. 26.7%) are also very similar. These findings suggest that the issue of sample selection into our small sample may not be as grave as feared.

The importance of application form information in the hiring process

Human resource officers typically use information from the documents stage to infer candidates’ skills, motivation, personality, and job fit (Cole et al. 2003, 2007). Application forms are a major source of such information.3 According to the interviewed HR officers, personal background questions provide employers with the following four general sets of information: job-specific skills, obstacles to working effectively, ability to harmonize with the firm, and dedication to the firm. The first set of information sought relates to the needs of particular openings. For most jobs, employers look for candidates with problem-solving ability, creativity, passion for the job, leadership and pro-activeness. Some firms that ask more personal questions report that, among applicants with similar qualifications, they look for those with “well-rounded” backgrounds. In addition to these general characteristics, candidates should possess job-specific skills. Questions about eyesight and color blindness are important in precision occupations, and in laboratory and factory jobs. Ability to drink alcohol is desirable in jobs requiring frequent contact with clients and participation at receptions (Lee & Rowley, 2008, p. 162). According to one interviewee, even when personal questions pertain to only specific positions, firms with job-rotation or promotion systems may ask these questions to all applicants.

Regarding applicants’ appearance, interviewees differ in the importance they attribute to it. Refer to Table 1. On a 1-5 Likert scale, the mean reported importance is 2.86, slightly lower than the middle of the Likert range corresponding to medium importance. According to one HR officer, applicants’ appearance is important for front-office workers, secretaries, reporters and consultants, as their appearance helps to establish good impression and trust during interpersonal dealings. An applicant’s photograph carries different importance across firms too. The mean reported importance is 2.25. One interviewee, an HR department clerk, mentions that his office judges the reliability of the content of an application form by how trustworthy the applicant appears in his photograph. Another interviewee explained that the purpose of questions about applicants’ height and weight is to exclude outliers such as highly obese or short individuals. At his firm, the questions are not intended to identify superior applicants under some subjective standard of beauty. Physical traits are surveyed merely to sieve out outlying applicants. But he added, good appearance may still be an advantage when an applicant satisfies other prerequisites.

Some interviewees, however, say that appearance is evaluated only in person at the interview stage rather than from a photograph on an application form. This is because recruiters care about applicants’ looks in reality, but the limited features in applicants’ photographs do not reveal those. Four interviewees also mentioned that the photograph may affect an applicant’s outcome negatively if it is very different from the applicant’s true look.

The next type of information sought by recruiters concerns any physical obstacle or inconvenience that would prevent workers from working effectively. Questions about health status and chronic diseases help to evaluate this. Six out of fifteen firms in our sample ask male applicants about the reason for their discharge or exemption from military service. Also, five firms ask applicants to undertake a physical examination before getting officially hired. Their officers argue that physical examinations are important for their firms because certain diseases may harm workers’ own work, their coworkers, and the firm at large.

The third set of information ascertains applicants’ ability to fit in with the firm’s existing workforce. Most interviewees state that applicants should possess the ability to adjust to the specific needs and organizational structure in a firm, including the ability to harmonize with coworkers, submit to the culture of the organization, and contribute to it in the long term. Religion may be surveyed to screen out applicants with abnormal views, social skills, or needs from a job. Religion is also an indicator of a well-rounded personality, according to one HR officer. Employers only consider whether an applicant comes from one of the mainstream religions. If an applicant comes from another persuasion, he may hold abnormal views on certain subjects, which may hinder his ability to harmonize in the workplace.

Finally, as the fourth set of information, applicants’ financial status and the financial status of their parents indicate whether they would work for the firm in the longer term. According to one interviewee, poor employees have a higher tendency to move when they are offered a higher salary elsewhere. Another interviewee explained that applicants’ dwelling type indicates their fixed monthly expenditures, which affects their desired structure of compensation. Employees with rental housing allegedly need higher base salary to pay monthly wolsae rent, or principal and interest on chonsae housing deposits, so they seek jobs with a higher base salary than house-owners or those who live in their parents’ house. Marital status and family background proxy for applicants’ willingness to move for work. According to one employer who has branches in several provinces, and asks for addresses of applicants’ family members, and when an applicant’s spouse works in another province, this applicant would have a higher tendency to accept a job offer near the spouse’s home or workplace. Furthermore, workers’ productivity, regardless of gender, may suffer if they live far from their spouses.

The observed distribution of questions across firms’ application forms and firms’ justification for them appear to confirm that firms screen information systematically and hierarchically. Most firms screen factors that are more directly informative of applicants’ productivity or loyalty, and less intrusive, and only some firms continue on to screening less directly informative and more intrusive characteristics (Hlasny, 2014).

Our interviewees denied that screening using personal questions is discriminatory. One interviewee explained that personal information is more predictive of applicants’ productivity than standardized test scores. For example, whether an applicant lives 100km away from the firm has greater bearing on his productivity than a score of ten more points on the Test of English for International Communication (TOEIC). Personal questions are also allegedly intended to promote affirmative action. Applicants’ disability is allegedly surveyed to offer preferential treatment to disabled workers, in compliance with the Act for the Employment Promotion and Vocational Rehabilitation of Disabled Persons. Questions about religion, birthplace, military service or age may be asked to comply with the organization’s founding principles, or with legal age limits.

Applicant Screening at Different Types of Firms

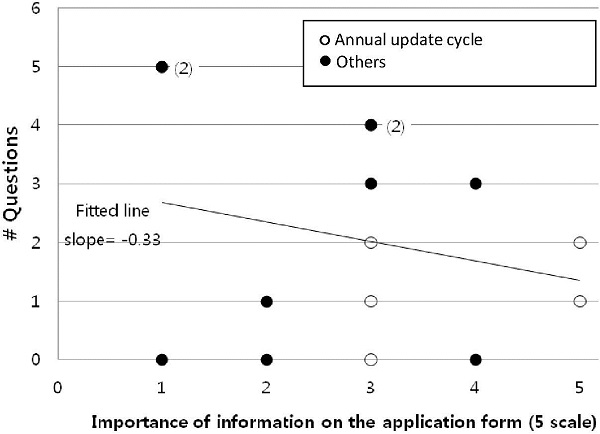

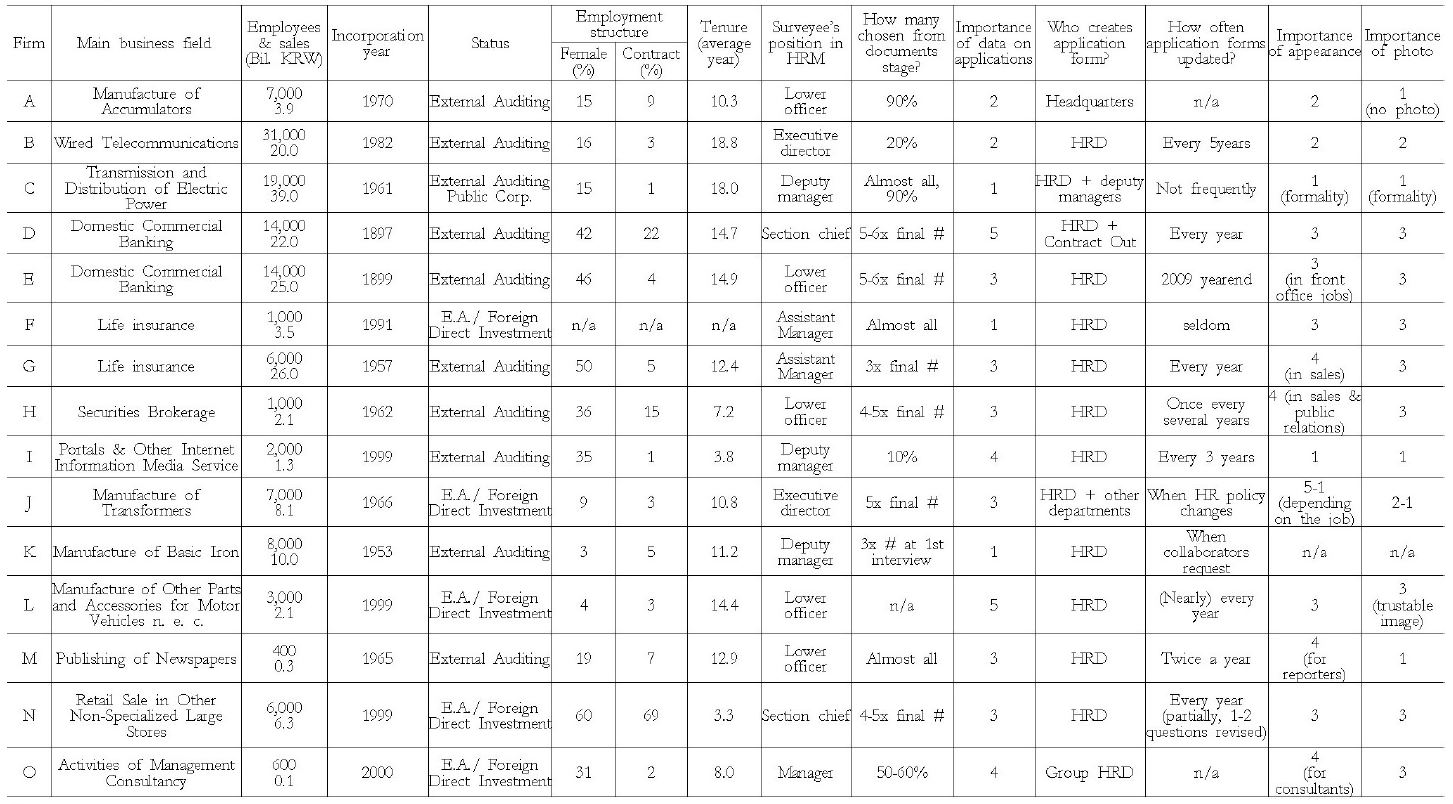

Having evaluated the composition of firms’ application forms, we may start noting patterns between employers’ characteristics or broader human resource practices, and the number of personal questions asked. Figure 1 shows that more mature firms tend to ask more personal background questions than younger firms. This is consistent with prior anecdotal and statistical evidence of a positive relationship between the extent of applicant screening, and the age of firm’s current majority owner or founder (Hlasny, 2009). Both of these trends may be explained by inertia in firms’ responses to changing regulatory conditions and new laws. Figure 2 appears to confirm this conjecture. Employers who update their application forms more frequently, and are thus less susceptible to inertia, tend to ask fewer personal questions today.

Firms’ type and year of incorporation, and the count of personal questions askedNote: Pearson correlation coefficient is -0.30.

Firm type, update cycle of application forms, and the count of personal questions askedNote: ‘Not regularly’ denotes updating of application forms when the firm HR policy changes, when business partners request it, or on another arbitrary date (say, 2009 yearend).

Figure 1 indicates another interesting relationship – that between the firms’ ownership structure and the number of personal questions asked. Domestic firms tend to ask significantly more personal questions than multinational and foreign direct investment corporations. The latter firms are among the youngest in our sample. Hence, changing ownership structure across firm cohorts provides another account for why more established firms appear to ask more personal questions on application forms. For alternative explanations, or to explain why some firms update their applications more often than others, we would need to turn to conjectures about the business environment in which firms operate, about firm hierarchy and adaptability of firms’ management style, or about owners’ moral standards. Unfortunately, such information is unreliable or missing, and we have too few observations for different types of firm (various industries, local labor markets, firm organizational structures, founder personalities etc.) to draw reliable conclusions.

Industry does appear to be associated with the extent and type of applicant screening. Among the industries represented more heavily in our sample, manufacturing firms appear to ask more personal questions than financial and insurance firms. Manufacturers inquire about applicants’ birthplace, family background, and physical conditions more often than firms in other industries. Financial and insurance firms ask more about home ownership and religion. The only firm in our sample asking about the ability to drink alcohol is a publishing firm. These facts are consistent with a prediction that firms inquire about characteristics that have bearing on applicants’ performance on the job. Different requirements for skills across industries and types of firms give rise to different forms of screening. Because of small sample size, however, it is impossible to determine how important industry classification is in driving the observed pattern of screening practices across firms. Even among firms facing similar business conditions – industry, incorporation years and size – we observe quite diverse application forms. Differences in human- resource institutions, practices and attitudes at different firms may explain this. The following paragraphs explore the limited available evidence.

The Role of Human Resource Management

Two properties about recruiting practices that are relevant to this study and that notably vary across firms are frequency with which they update their application forms, and familiarity with discrimination laws reported by their HR officers. Figure 2 shows that employers updating their application forms more frequently tend to ask fewer personal questions. Difference in means of the number of questions between the annually (6 firms) and less-frequently updated application forms (7 firms) is highly statistically significant. Firms exhibiting inertia in responding to regulatory conditions are stuck with an older, larger set of personal questions today. Secondly, the observed inertia may reveal something about firms’ latent attitude toward application forms. Firms that assign greater importance to application forms, or their appropriateness, may keep them more up to date and more consistent with legislation.

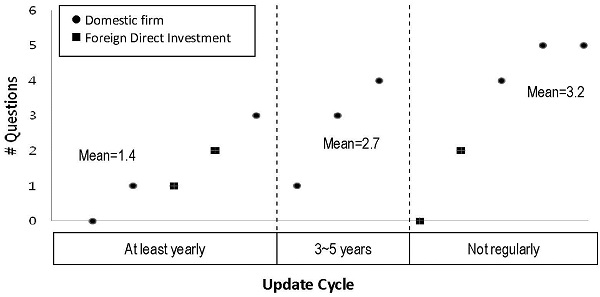

Figure 3 provides more evidence on firms’ attitudes. Firms whose officers are allegedly familiar with discrimination laws are shown to ask fewer personal questions than other firms. The difference between the two group means – 1.5 and 4.3 – is highly statistically significant. The officers’ responses to why each personal question appears on their application form are equally interesting. The four officers who ostensibly believe that it is a firm’s right to know applicants’ personal background all work at firms asking many personal questions (black diamonds in Figure 3). Two other officers at firms asking many personal questions claim that information on application forms is not crucial to hiring decisions (black dots). We may interpret these trends in a number of ways. Firms with better informed HR departments may adopt less intrusive recruiting practices. Furthermore, employers who believe that they have the right to know applicants’ personal background tend to inquire about it, even if the benefit of the information is small. Alternatively, these responses may simply serve to rationalize firms’ observed behavior. Employers caught asking intrusive questions may claim that they lack knowledge of pertinent laws, believe that the questions are warranted, or claim that they don’t use the collected information to discriminate. Next, we turn to employers’ perceptions of the importance of personal questions.

Interviewees’ familiarity with discrimination laws, importance of personal questions, and the count of personal questions asked

Some officers emphasize that they use personal information only at a later stage of recruitment, during interviews. They do not reject applicants in the documents stage based on their personal information. On the other hand, firms that do not ask personal questions report that they focus more on applicants’ skills and ability than on their personal background in all stages of recruitment. One plausible interpretation is that, in the use of personal information, the documents stage is representative of other stages of the overall recruitment process at firms. Firms asking personal questions on application forms use this information one way or another – in the documents stage or the interview stage – while firms with short application forms truly ignore personal information. Another possibility is that personal considerations taint the decisions in the interview stage at all firms, and the prevalence of personal questions on application forms is irrelevant to the eventual use of personal information. Officers’ responses may simply be evasive. Employers caught asking for personal information downplay its importance – at least in the documents stage – while firms who are not caught never acknowledge considering this information.

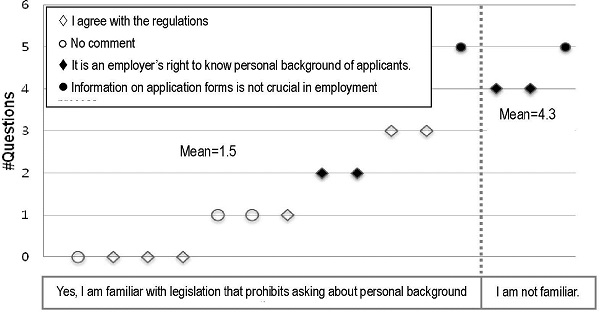

Figure 4 considers explicitly the importance that firms reportedly attribute to application forms. The importance of application forms in decision- making about applicants varies significantly across firms, from one to five on the 1-5 scale (mean 2.87). On average, those who report importance of three points higher tend to ask one personal question fewer. Higher reported importance of application forms is associated with higher frequency of updating of application forms at firms (white circles in Figure 4). Once again, this tendency may represent ex post rationalization by HR officers. Employers asking many personal questions may report lower importance of application forms to downplay the role of personal factors in recruiting.

Consequences of Screening on Workforce Composition

To independently evaluate the impact of firms’ recruiting practices on the composition of their workforce, Figures 5 and 6 plot the number of personal questions against the average continuous working years, and the gender ratio among the firms’ current workforce. HR officers claim that a primary reason for asking personal questions is to infer applicants’ expected tenure with the firm. However, Figure 5 shows that there is extremely weak correlation between the questions asked and workers’ tenure. Knowledge of applicants’ personal information does not appear to help predicting their long-term performance at the firm. Employers who ask 3-5 personal questions tend to have essentially the same average tenure among workers as employers asking 0-2 questions.4 A similar result was obtained for the relationship between the extent of screening and firms’ overall prosperity. The correlation between the number of questions in 2008, and firms’ net profit for 2009 is -0.32, suggesting at face value that expending resources on applicant screening may actually hurt firms. At the same time, Figure 6 shows that employers asking more personal questions tend to have a lower fraction of women (correlation -0.28) than employers asking fewer questions.

Application-form update cycle, average employee tenure, and the count of personal questionsData source: Financial Supervisory Service.Note: Pearson correlation coefficient is +0.14.

Firms’ gender ratio, and the count of personal questionsData source: Financial Supervisory Service.Note: Pearson correlation coefficient is -0.28.

On the face value, evidence in Figures 5 and 6 supports the allegation that firms’ screening practices contribute to discrimination in hiring even more than they affect quality of the hired workers, or firms’ overall performance. If we believe the causal interpretation of the figures, we may conclude that the employers, in attempting to sieve out high-turnover applicants, incidentally disqualify some protected groups of workers such as women. For every additional personal question asked, the predicted fraction of women falls by 36 percentage points.5

Returning to the standards of appropriateness (Arvey & Renz, 1992), the recruiting practices identified in this study may conform to the criterion of procedural justice, as the surveyed personal characteristics are objective and are evaluated by a professional team of HR officers. Most information collected by firms is dispassionate (with the exception of appearance surveyed from photographs or during interviews), not subject to interviewers’ interpretation and straightforward for applicants to measure and provide. The recruiting practices may, however, violate the legality and content-fairness criteria of appropriateness. Some of the questions asked by employers are in explicit violation of the Act on Equal Employment and Support for Work-Family Reconciliation (Article 7). Furthermore, many questions are not merit-based or sufficiently job-related, and are invasive to applicants’ privacy. To the extent that these recruiting practices result in the hiring of fewer women or other protected individuals, the practices may be in violation of outcome fairness. Unfortunately, reliable data at the level of individual applicants are missing.

Career, a Korean online recruiting portal, surveyed 1,016 applicants on their views about the appropriateness of questions on application form s.6 The results agree with our conclusion that applicant screening practices at Korean firms may be problematic in terms of both content and outcome fairness.

Conclusion

This study has tried to explain Korean employers’ applicant screening practices by their business environment, their broader human resource management system, and HR officers’ own justifications and attitudes. Our results extend the evidence from previous studies regarding the role of screening of personal factors in recruitment. For example, the NHRC (2003b) reported that firms asked about applicants’ religion to judge their availability to work on holidays, while employers in our sample reportedly ask about it to judge applicants’ “commonality” and ability to harmonize with the rest of the firm, a more plausible explanation.

In addition, our interviewees confess that family background is used as a predictor of applicants’ economic situation. Ultimately, applicants’ economic situation serves to predict their tendency to remain on the job in the long term. Here, the tradeoff from the employers’ perspective is that disadvantaged employees may be more willing to quit in pursuit of a higher salary, but they may also be more loyal in order to protect their jobs. Empirically, however, firms don’t appear to be very successful at predicting workers’ future tenure with them. The average experience of workforce is similar across firms asking many or few personal questions. If we account for the higher age of firms screening extensively, the effect on average tenure becomes negative. Firms’ overall profitability also appears negatively related to the extent of screening. On the other hand, firms asking more personal questions tend to have a significantly lower ratio of women among their workers. In attempting to sieve out high-turnover applicants, employers may be incidentally disqualifying some protected groups of workers, to the workers’ and perhaps even their own detriment.

According to our interviews, most recruiters believe that screening based on personal characteristics is a legitimate way to collect necessary job-related information about applicants. But this perceived need should not be viewed as real benefit of applicant screening. First, the information obtained is an imperfect predictor of applicants’ skills, and may lead to the hiring of even inferior workers. Indeed, firms never learn the true productivity of applicants whom they reject, and their justification for their screening practices is hypothetical. Second, it is unclear how firms actually use the information they collect. Interviewees’ responses give an impression that firms collect applicants’ personal details simply to get a sense of security of having relied on a thorough decision-making process and controlled for all contingencies, rather than to obtain any valuable information in itself. The commonplace practice may reflect the effortlessness or low short-term cost of applicant screening, rather than any long-term benefit from it.

Recruiters reportedly seek workers who can harmonize well with their firm, but may overlook the fact that their organization is dynamic and that another sort of workers may be needed for the firm’s long-term growth. This tendency may reflect the recruiters’ aversion to change or their instinct to safeguard their own jobs, rather than real intention to seek out future talent. Applicants who are capable of adjusting to the existing corporate culture and who will promote this culture proactively and passionately may not be the best workers for the future. The evidence from interviews suggests that organizations underplay their own responsibility to harmonize with new workforce and their own need to evolve. Previous studies have shown that organizations that accept diversity tend to be more successful than those that do not (Wright et al. 1995). This study provides some confirmation of this. Prejudice against applicants’ personal backgrounds may not only legally but also economically harm them. Finally, even if personal screening practices ended up helping individual firms in the short term, they distort applicants’ incentives to accumulate qualifications, and may hurt long-term productivity and growth in the overall economy. They may also breed discord and casteism in the Korean society at large.

These findings should prompt greater introspection by HR departments into their screening practices, and closer scrutiny by market regulators. HR departments should calibrate their practices more carefully and frequently, to align them with their underlying long-term objectives and with social aims. Regulators should usher in market conditions conducive to these efforts – through civic education campaigns, publicizing of appropriate social norms, and enforcement of minimum standards of responsible recruiting practices.

Glossary

1 Our sampling is biased toward larger and urban employers. There is some evidence that smaller and rural employers ask more personal questions, and may provide different responses to our interview. However, large firms in the Seoul metropolitan area, provide a disproportionately larger number of jobs, and attract a larger than average number of applicants per opening. We may accept the potential selection bias in return for the greater relevance of the sample to the conditions faced by most Korean applicants. Furthermore, our convenience sample allowed us to conduct face-face interviews and collect accurate detailed responses, which would have been impossible with a larger sample.

2 In the NHRC (2003b) sample of 100 year-2002 application forms, 90% of firms asked about family background, 80% about physical conditions, 80% about the reason for military exemption, 29% about marital status, 64% about religion, 37% about birthplace, 17% about property, 36% about dwelling, 9% about financing of education, and 9% about acquaintances. These rates are higher than those found by Hlasny (2009), because of the passage of time, enactment of several discrimination laws, and direct intervention by the NHRC and MOEL between 2002 and 2008 (NHRC 2003a; MOEL 2011). Still, the prevalence of questions about birthplace, marital status, physical conditions, ownership, and financing of education remain similar across the two studies.

3 According to a Korean job portal survey of 349 HR officers, 34% of employers review carefully the entire application form and another 57% review carefully most items. Only 4% merely skim through them, and another 4% only review particular items. (http://www. saraminhr.co.kr/open_content/pr/press_release.php, accessed 11.16.2010.) Employers reportedly place the greatest weight on applicants’ work experience (most important for 57% of surveyees), personal background (9.2%), name of university (5.7%), other certifications (4.6%), foreign languages (4.3%), and education level (3.2%).

4 The weak positive relationship (correlation +0.14, statistically insignificant) may be explained in several ways. It may be caused by a positive correlation between firms’ age and workers’ average work experience (correlation +0.45). The workforce of firms that were established in the late 1990s cannot have tenure over 15 years today. Excluding the four firms established in 1999 or 2000, correlation between the number of personal questions and average tenure falls to +0.03.

5 One caveat is, of course, that we cannot identify a direct or even one-way causal effect of hiring practices on the composition of firms’ workforce. Workforce composition depends on many events after the rendering of a job offer, such as acceptance by the worker, maternity leave, termination, own resignation etc. Current composition of workforce, and firms’ satisfaction with it, may have a feedback on firms’ recruiting objectives and practices.

6 Some questions about educational background were deemed discriminatory (by 92% of respondents), as were questions about occupation and financial status of family members (52%), age (49%), physical condition (40%), religion (16%), military service (15%), and photograph (14%) (Online Survey of Applicants, www.career.co.kr, accessed on 15-October 2011). These questions were deemed discriminatory because they covered personal details that were not needed in the hiring process (17% of respondents), they were unrelated directly to job skills (44%), they prevented applicants from demonstrating their true ability (20%), or they were based on applicants’ social status (17%).

References

- R. D Arvey, & G. L Renz, (1992), Fairness in the Selection of Employees, Journal of Business Ethics, 11(5/6), p331-340.

-

M. R Barrick, M. K Mount, & T. A Judge, (2001), Personality and performance at the beginning of the new millennium: What do we know and where do we go next?, International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 9(1), p9-30.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2389.00160]

-

L Borghans, A. L Duckworth, J. J Heckman, & B ter Weel, (2008), The Economics and Psychology of Personality Traits, Journal of Human Resources, 43(4), p972-1059.

[https://doi.org/10.1353/jhr.2008.0017]

-

L Bennington, & R Wein, (2000), Anti-discrimination Legislation in Australia: Fair, Effective, Efficient, or Irrelevant?, International Journal of Manpower, 21(1), p21-33.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/01437720010319435]

- M. S Cole, H. S Feild, & W. F Giles, (2003), Using Recruiter Assessments of Applicants’ Resume Content to Predict Applicant Mental Ability and Big Five Personality Dimensions, International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 11(1), p78-88.

- M. S Cole, R. S Rubin, H. S Feild, & W. F Giles, (2007), Recruiters’ Perceptions and Use of Applicant Resume Information: Screening the Recent Graduate, Applied Psychology: An International Review, 56(2), p319-343.

- Financial Supervisory Service, Semiannual Reports, (n.d), Retrieved June 30, 2011, from individual firms’ pages at http://dart.fss.or.kr.

-

S. W Gilliland, (1993), The Perceived Fairness of Selection Systems: An Organizational Justice Perspective, Academy of Management Review, 18(4), p694-734.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/258595]

- S. W Gilliland, (1995), Fairness from the Applicants’ Perspective – Reactions to Employee Selection Procedures, International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 3(1), p11-19.

- S Harcourt, & M Harcourt, (2002), Do Employers Comply with Civil/Human Rights Legislation? New Evidence from New Zealand Job Application Forms, Journal of Business Ethics, 35(3), p207-221.

-

M Harcourt, G Wood, & S Harcourt, (2004), Do Unions Affect Employer Compliance with the Law? New Zealand Evidence for Age Discrimination, British Journal of Industrial Relations,, 42(3), p527-541.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8543.2004.00328.x]

- M Harcourt, H Lam, & S Harcourt, (2005a), Unions and Discriminatory Hiring: Evidence from New Zealand, Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 44(2), p364-372.

-

M Harcourt, H Lam, & S Harcourt, (2005b), Discriminatory Practices in Hiring: Institutional and Rational Economic Perspectives, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 16(11), p2113-2132.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190500315125]

- J. J Heckman, J Stixrud, & S Urzua, (2006), Noncognitive Abilities on Labor Market Outcomes and Social Behavior, Journal of Labor Economics, 24(3), p411-482.

- V Hlasny, (2009), Patterns of Profiling of Applicants by Korean Employers: Evidence from Job Application Forms, Journal of Women & Economics, 6(1), p1-29.

-

V Hlasny, (2011), Discriminatory Practices at South Korean Firms: Quantitative Analysis Based on Job Application Forms, European Journal of East Asian Studies, 10(1), p85-113.

[https://doi.org/10.1163/156805811X592522]

- V Hlasny, (2012), Economic Determinants of Applicant Screening Practices: An Empirical Analysis of the Human Capital Corporate Panel, Proceedings of the 4th HCCP Conference, Seoul, Korea.

- V Hlasny, (2013), Four Pillars of Job Applicant Screening in China, Working paper for Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Korea.

-

V Hlasny, (2014), A Hierarchical Process of Applicant Screening by Korean Employers, Journal of Labor Research, 35(3), p246-270.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-014-9183-7]

- V Hlasny, & M Jiang, (2012), Recruitment in China: An Employer-Level Analysis of Applicant Screening, Working paper for Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Korea.

- J. P Jolly, & J. G Frierson, (1989), Playing it Safe, Personnel Administrator, 34(6), p44-50.

- Korea Ministry of Employment and Labor (MOEL), (2007), The Guideline of Standard Application Form, MOEL press report, 25-Nov 2007.

- Labor Law: Equal Employment, (2011), Retrieved September 10, 2011, from http://laborstat.moel.go.kr.

- P Kuhn, & K Shen, (2009), Employers Preferences for Gender, Age, Height and Beauty: Direct Evidence, NBER Working Paper Series, w15564.

- P Kuhn, & K Shen, (2013), Gender Discrimination in Job Ads: Theory and Evidence, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(1), p287-336.

- J. H Lee, & C Rowley, (2008), The Changing Face of Women Managers in South Korea. In C. Rowley & V. Yukongdi (Eds.), The Changing Face of Women in Asian Management, p148-170, London: Taylor & Francis.

- K. W Lee, K. S Cho, & S. J Lee, (2001), Causes of Gender Discrimination in Korean Labor Markets, Asian Journal of Women’s Studies, 7(2), p7-38.

- S. S Lee, (1994), Sexual Discrimination in Hiring, Philosophy and Reality, 23, p229-240, [in Korean].

-

A. L Light, & M Ureta, (1992), Panel Estimates of Male and Female Job Turnover Behavior: Can Female Nonquitters be Identified?, Journal of Labor Economics, 10(2), p156-181.

[https://doi.org/10.1086/298283]

-

J. W Moy, & K. F Lam, (2004), Selection Criteria and the Impact of Personality on Getting Hired, Personnel Review, 33(5), p521-535.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480410550134]

- NHRC, (2003a), Major Companies Deleted Discriminatory Questions on Their Job Applications, NHRC press report.

- NHRC, Rectification of Discriminatory Items on Application Forms, NHRC press report. 26-June 2003, (2003b).

- S. J Park, (1990), Structural Aspects of Sex Discrimination in the Korean Labor Market: The Screening Process of Recruitment, Korean Social Science, 2, p48-74.

- E. S Phelps, (1972), The Statistical Theory of Racism and Sexism, American Economic Review, 62(4), p659-661.

- D. M Saunders, J. D Leck, & L Marcil, (1992), What Predicts Employer Propensity to Gather Protected Group Information from Job Applicants? In D. M. Saunders (Ed.), New Approaches to Employee Management: Fairness in Employee Selection, p105-130, Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

-

D. M Truxillo, D. D Steiner, & S. W Gilliland, (2004), The Importance of Organizational Justice in Personnel Selection: Defining When Selection Fairness Really Matters, International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 12(1/2), p39-53.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0965-075X.2004.00262.x]

- J. C Wallace, M. G Tye, & S. J Vodanovich, (2002), Applying For Jobs Online: Examining the Legality of Internet-Based Application Forms, UN report.

-

P Wright, S. P Ferris, J. S Hiller, & M Kroll, (1995), Competitiveness through Management of Diversity: Effects on Stock Price Valuation, Academy of Management Journal, 38(1), p272-287.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/256736]