The Production of a Gendered Space: Reading Women’s Landmarks in Anping, Taiwan

This study explores how Anping, one of the most significant cultural centers in Asia, has been transformed into a gendered space. To read Anping as a gendered space, this paper, based upon news reports and intensive interviews with participating agents in the community, will focus on the only two officially designated women's landmarks in the region as the subjects of textual analysis. I will show the process of the production and representation of Lin Mor Niang Park and the statues of Miss Jin as well as her mother. First, I will analyze how metaphors of gender inscribed in the landmarks are employed to reinforce dominant gender stereotypes. Next, I will explore how the women's landmarks have turned into the most desirable forms of contemporary cultural capital related to a growth in tourism and a shift towards an entrepreneurial form of urban governance. Indeed, gender is not only constitutive of, but virtually indispensable to, the configuration of the place. In contrast to the current masculine version of Anping’s map, which is full of military and colonial landmarks, this study seeks to enrich Anping’s outlook by identifying significant sites particularly associated with female representatives of their time. My purpose is to produce a new way to understand the city’s cultural landscape by locating women’s stories in the mapping of Anping’s history. By representing the new visual modalities such as Lin Mor Niang Park and Miss Jin’s statue into the current mapping, this study can contribute to what might be called a feminist politics of place construction.

Keywords:

Women’s landmarks, gendered space, feminist geographyIntroduction

Since the cultural turn of human geography, space and place are increasingly regarded as socio-cultural constructions rather than as physical locations. In particular, the perspectives of feminists have influenced the methods and practices of critical human geographies through their emphasis on the importance of foregrounding women as a subject of study and “gender” as a social and spatial process. By using gender as a social and/or spatial construct, feminist geographers have critiqued the idea of gendered identities and spaces as “natural.” Instead, they have recognized the spatialized construction of femininity and masculinity. For instance, feminist geographers such as Doreen Massey, Linda McDowell, and Gillian Rose contributed much of their work to gender roles and gender inequality in the production of space. Nevertheless, some feminists argue that working with gender as the most significant difference homogenizes and simplifies the diversity and complexities of individuals’ experiences (Women and Geography Study Group, 1997, p. 80). Contemporary feminist geographers, therefore, have broadened their focus beyond the binary division of male/female towards the social construction of gender identities/relations across a variety of contexts, and by interweaving the importance of race, ethnicity, nationality, sexual orientation, colonialism, culture, and class (Valentine, 1993; Blunt, 1994; Kobayashi, 1994; Mills, 1996; Radcliffe, 1996). Indeed, women from a multiplicity of racialized, sexualized, classed, and transnational experiences have been exploding the canon of feminist geography (Al Hindi, 2000).

While gender relations and gender roles located within various geographic and historical contexts are increasingly examined beyond the horizon of white, middle-class and Western spaces, it was not until very recently that gender became an issue for serious analysis in human geography in Asia. As Saraswati Raju (1993) notes, “Although geographical research on women has yet to develop a cohesive feminist perspective and an abiding interest among South Asian geographers, a beginning has been made” (p. 79). More and more Asian feminist scholars such as Brenda S. A. Yeoh, Lily Kong, Luh Sin, and Shirlena Huang have paid attention to geographical analysis of gender issues and attempt to incorporate women as subjects for geographical inquiry. However, according to Chiang and Liu (2011), “Feminist geography in both Hong Kong and Taiwan has progressed at a very slow pace, due to the small proportion of female professors and a general lack of feminist consciousness among geographers. However, at least in the case of Taiwan, there are indications of growing attention to feminist geography among the younger generation of female geographers” (p. 566). In response to such feminist calls for women’s critical engagement with geographical spaces, the researchers at the Center for Women and Gender Studies at National Cheng Kung University have collaborated on an interdisciplinary project “Women Mapping Anping” in an attempt to envision women’s everyday experiences in Anping and examine the effects of municipal representational practices on the changing landscape of their city.1

This study, part of the collaborative project, explores how Anping, one of the most significant cultural centers in Asia, has been reconstructed into a gendered space. To read Anping as a gendered space, this paper, based upon news reports and intensive interviews with participating agents in the community, will focus on the only two officially designated women’s landmarks in the region as the subjects of textual analysis. I will show the process of the production and representation of Lin Mor Niang Park and the statues of Miss Jin as well as her mother. First, I will analyze how metaphors of gender inscribed in the landmarks are employed to reinforce dominant gender stereotypes. Next, I will explore how the women’s landmarks have turned into the most desirable forms of contemporary cultural capital related to a growth in tourism and a shift towards an entrepreneurial form of urban governance. Indeed, my study has found that gender is not only constitutive of, but virtually indispensable to, the configuration of the place. In contrast to the current masculine version of Anping’s map, which is full of military and colonial landmarks, this study seeks to enrich Anping’s outlook by identifying significant sites particularly associated with female representatives of their time. My purpose is to produce a new way to understand the city’s cultural landscape by locating women’s stories in the mapping of Anping’s history. By representing the new visual modalities such as Lin Mor Niang Park and Miss Jin’s statue into the current mapping, I shall contribute to what might be called a politics of place construction.

Re-mapping Anping

Located in the southwestern part of Tainan, the city of Anping was called Tayouan, which is where the word “Taiwan” comes from. As a natural harbor, it was one of the earliest developed areas in Taiwan. Once a military fort, a capital for politics, and a center for economy, Anping-now a national historic park in Taiwan-has been transformed continuously since the late 17th century in the tides of Western colonialism and globalization. Built by the Dutch in 1624 as the first western settlement in Taiwan, it changed considerably during the years of the sovereign rule of Ming, Ching, Japan, and the subsequent R.O.C government. In 1624, the city was occupied by the Dutch and they built up the Zeelandiain, a castle used for the political and economic center. However, in 1662, Koxinga, a resister against the Ching Dynasty, escaped from China and took over the city after defeating and expelling the Dutch army out of Zeelandia. Koxinga renamed the city “Anping” and started to build many constructions in Anping and treated Anping as an important base for fighting back against the Ching Dynasty. Unfortunately, Koxinga failed and Anping was occupied by the Ching Dynasty. Under the occupation of the Ching Dynasty, Taiwan was attacked by Japan several times. In 1895, the Ching Dynasty lost a war to Japan, so Taiwan was taken over by Japan. During the Japanese colonization, other harbors, such as Kaohsiug Harbor, started to be developed so Anping gradually lost its strategic edge. Fifty years later, Taiwan was returned to China at the end of the World War II. Under the rule of R.O.C. government, some of the historical sites in Anping have been preserved and rebuilt and the city is now promoted as an area with rich Taiwanese history and culture.

With a rich historical and cultural heritage, Anping, in culturally defined geographic terms, refers not merely to an urban space but to a place full of diverse socio-spatial relationships. Many previous studies of Anping offer partial understandings of the dynamics of the place, because they focus largely on its historical reconstruction to the virtual exclusion of gender matters. In the official history of Anping, the female figures have always been absent. A review of the existing landmarks in Anping landscape provides an indication of the identity the local dominant culture has sought to produce. The statuary subjects include war and esteemed heroes. Unrepresented in bronze and granite, women’s histories have gone almost entirely unrecorded. While a tour of such attractions of heritage might inform tourists about some of our forefathers, there was no information about our foremothers because women were invisible from the local domestic history as well as from national political history and heritage.

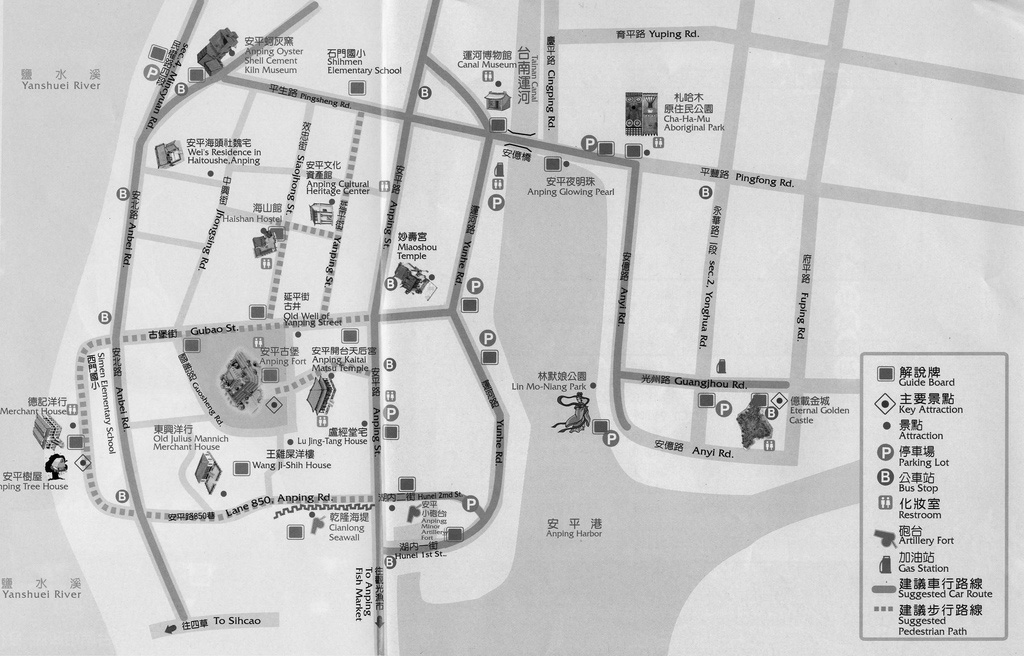

Official Anping map for touristsSource: Tainan City Government Tourism BureauNote: Lin Mor Niang Park is recently added as the only women’s landmark in this map. The statues of Miss Jin and her mother are not included in the map yet.

Only just recently, facing the challenges of the competition of the Global tourism industry, Tainan City Government has reconstructed Anping as a “National Anping Harbor Historic Park” by assessing its historical and cultural advantages.2 As a former capital in Taiwan Anping is now marketed by the local government as a prominent cultural center, one that is vital to matters of identity, representation and relationships that are “indigenous” to Taiwan. To promote its tourism policy, the local government actively employs “traditional” images of Chinese women in its efforts to draw visitors. Consequently, the local government established landmarks associated with women in its propaganda. Yet, the question remains, do these landmarks really represent Anping women? To provide an answer, this study will examine the gender implication of the officially designated women’s landmarks in order to produce a more inclusive portrait of Anping’s history. In particular, in the project I shall analyze the conditions and means of the production of women’s landmarks in Anping. Questions to be addressed include: when did the landmarks appear? In what forms were they constructed? What has been implied by their emergence? Additionally, the investigation will re-interpret the construction, and gender implications of the women’s landmarks and, at the same time, disclose, perhaps paradoxically, how such landmarks are constructed as part of patriarchal and capitalist hegemony.

The Legend of Lin Mor Niang and Matsu Culture

Matsu is a major female deity in Taiwan. According to legend, Lin Mor Niang was born in 960 C.E. (during the early Northern Song Dynasty) as the seventh daughter of Lin Yuan on Meizhou Island, Fujian. She was particularly devoted to the Buddhist deity Guanyin and, following her example, refused to marry, a decision that was very unusual for a young Chinese woman (Maspero, 1981). At a young age, Lin Mor Niang went into a trance during a storm and used her supernatural powers to save three of her four brothers from being lost at sea; she was roused from her trance before she could save the fourth brother (Irwin, 1990). She died soon afterwards (Maspero, 1981). She was worshiped as the patron goddess of sailors and seafarers under the name of “Ma Tsu” (Paper, 1989). The worship of Matsu came into being in the eleventh century and developed rapidly over the next hundred years (Maspero, 1981). According to Maspero, in 1155 C.E. the goddess received her first of many official titles--Princess of Supernatural Favour (1981). According to the historical records of Tien-Fei (Heaven Empress) Palace, the first temple of Matsu in Taiwan, the Matsu idol was carried from Meichou, Fukien Province of Mainland China, across the sea by Cheng Cheng-Kung, the Yen Ping Prefect of the Ming Dynasty in 1661 when he advanced eastwards to take Taiwan as a foundation to resist the central Ching government. When the navy was troubled by the ebb of the tide near Luermen, the Goddess Matsu manifested herself to guide them safely to shore. For that, pioneer settlers constructed her first temple in Anping to credit her with protecting them on their trip across the Taiwan Strait.

Since then, Matsu-worship has become rather popular in Taiwan, Matsu culture, which is developed from Matsu belief, has been gradually integrated into part of Taiwan folk custom and culture. Each year thousands of people are involved in Matsu pilgrimages. No longer is she only the protectress of fishermen or seafaring traders, but has taken on social functions as well. The Taiwanese people have developed special affection for the goddess as their patron saint or mother ancestor (Tischer, 2012). Some scholars recognize that Matsu culture has had a great impact on the contemporary Taiwan’s political, economic, cultural and social construction. (Tischer, 2012; Yang 2004; Sangren, 1983). While Sangren (1983) claims that “Ma Tsu cult has an inclusive effect among Taiwanese (uniting otherwise competitive Hakka, Chang-chou, and Chuan-chou factions)” (p. 16), Mayfair Mei-hui Yang (2004) believes that Matsu culture could promote cultural exchanges between Taiwan and China and redraw the boundary between communities long separated from one another. Clearly, Matsu culture plays special social functions such as providing community integration and cultural identification for the Taiwanese people.

The Cultural Politics of Naming

To provide clues as to the historical and cultural heritage of places and regions, geographers have analyzed the names of places. Yet, most of them have neglected struggles over the politics of place that often underlie naming processes. Nowadays, a growing literature is beginning to engage in a more theoretically informed discussion of the cultural politics of place naming (e.g. Azaryahu, 1996; Herman, 1999; Myers, 1996; Nash, 1999). For instance, there has been a recognition that place names “mark the spatiality of power relationships” (Myers, 1996, p. 237). On the significance of place-names among the Western Apache, Keith Basso (1983, 1996) has pointed out how the usage of place-names can serve as important indicators towards certain historical events and their geographical locations, and point towards the system of rules and values that organize and regulate the lives of individuals within the communities. According to Berg and Kearns (1996), place naming plays a key role in the social construction of space and the contested process of attaching meaning to places. Place naming thus involves a complex, intertwined set of social and political relations.

The naming procedure of Lin Mor Niang Park thus may provide insights into spatial perceptions and social relations. Since opened in April, 2004, Lin Mor Niang Park has become a significant landmark in Anping. Indeed, the naming process of the park has caused a lot of controversies and struggles. Like many religious statues, Lin Mor Niang statue, when it was first erected in the park in 2004, was offensive to Christian sensitivities. A concerned Christian community resisted the idea of placing a religious statue in a public space. Twenty-five ministers of Christian churches in Tainan City petitioned the city mayor against erecting the statue of Lin Mor Niang. Claiming that it would blur the boundary between religion and art and facilitate idolatry, the ministers hoped that the city government would separate art from religion. They advised that the statue of Lin Mor Niang could be put in Chi Mei Museum as a piece of artwork so that it would not prompt people to worship the statue.3 In order to respect the conflicting interests of different religious groups, the local government eventually named the park after Lin Mor Niang, her human name, rather than after Matsu, the religious title. “This is not intended to be a religious symbol,” said the mayor in his attempt to secularize the space (Rey, 2001).

Indeed, more than the material and symbolic artifacts of culture, place names can also become part of dominant values. The local government selected Lin’s maiden name to focus on what she did for her family before she was deified. To avoid the religious controversy, they claimed that Lin Mor Niang represents a model of filial piety, for she shows love, respect, and support for her family. According to one version of her legend, she tried to rescue her father and brother when they were suffering from a storm on the sea. Strong winds and rains destroyed their boat, and it disappeared on the waters. When Lin Mor Niang dived into the sea in hope of saving her beloved family members, she never returned to land. Therefore, the local official suggested that she should become a model for young people. Lin's image is thus used to inspire young people to further virtue and teach them a moral lesson. From this perspective, Lin Mor Niang is more about constructing a role model for the community than about presenting a religious icon for it. The act of naming the park therefore not only supports the cultural practice of filial piety, but also reveals the gender implication of naming places---reinforcing the dominant gender ideology positing that young women are to be encouraged to follow her type of feminine virtue by living for the family instead of for themselves.

Representing a Dutiful Daughter

The iconic statue in the park also reveals how its language and imagery are incorporated in feminine terms. Historically, the image of Lin has grown and evolved. The most common image of Matsu in the temples is similar to that of a queen, a benevolent, middle-aged woman wearing “archaic imperial regalia,” an emperor’s crown and a dragon robe (Paper, 1989, p. 33). Solemn and noble, the dark or golden figure in the temple relates to the visitors at a distance. According to Wen San Liu (2000), the facial features of Matsu’s statue are plump and round with long and curving eyebrows. Her mouth is small and somewhat parallel with her nose. Her eyes do not open widely but are looking down at her pilgrims serenely. She wears a thick and simple decorated gown with an embroidered dragon head and sits in a static state. Because she is regarded as “Heavenly Queen,” some of Matsu’s statues wear gowns and phoenix coronets. Looking majestic but not fierce, she appears benevolent and noble. Interestingly, as an officially sanctioned deity, this sovereign, elegant, dignified image also contains male attributes, for she often carries a tablet or scepter, symbols of official male power in Chinese feudal times.

Different from the conventional Matsu image without obvious feminine attributes in the temples, the statue of Lin Mor Niang, on the one hand, looks like a beautiful young woman. The height of the statue is 16 meters with a base 4 meters in diameter. Its materials are granite and very fluent. The massive carved statue was created by Wei Lee, an artist living in China. To avoid the controversy of establishing a religious statue in a public space, the statue is designed as a form of public art that expresses feminine beauty. Her image is constructed as a slim, graceful young lady who became immortal at the age of twenty-nine. Bigger than the other Matsu statues in the temples, the towering figure radiates an exalted beauty and stands at the harbor facing the sea. The artist not only gives her a more compassionate expression by softening the downward curve of her lips and her eyebrows, but also bestows on her a pliant charm, the traditional embodiment of oriental beauty. With her hair wavy and loose about her shoulders, she is dressed in a simple robe with a ribbon, indicators of her youth. In one hand she brandishes a fuchen and in the other holds a ruyi, symbols of good luck. Consequently, without losing her divinity, Lin’s statue creates a type of Chinese feminine beauty and grace and is expressive of kindness and generosity. The structure, a modern re-imagination of the ancient deity, is now appreciated as a cultural and aesthetic expression made more understandable and approachable to the secular mind.

On the other hand, the statue has also acquired the character of a mother. One local Taiwanese male poet composed a poem that was inscribed on a plaque on the statue’s base. Longing for her maternal care and tenderness, the poet, from a son’s perspective, invokes the popular image of Matsu as a mother figure. Although she neither married nor gave birth to children, Lin is widely respected as a holy mother of the sea, protector from harm, and provider of care in Taiwan. Her image is perceived as one like Holy Mary of Christianity or Guanshiyin Pusa of Buddhism. She is addressed as “Mother” and thus is embodied as the ideal of motherhood. When people are helpless and anxious, they tend to air their grievances to their common mother, and for these supplicants she is obviously a mother who can be trusted and relied on. In this respect, the poetic verses remind visitors that she is the mother- protector of her children, home, and the city. Yet, such poetic invocation not only suggests Lin as a native symbol of gender specific household roles but also further locates women within the domestic realm as mothers and caretakers. Imposing the conventional gender ideology of a mother as the home protector, the grandiose statue of Lin Mor Niang is a clear statement about how women’s roles are culturally envisioned. Being represented as both daughter and ideal mother, the statue becomes an iconic representation for veneration or emulation of female roles already culturally prescribed.

Gendered Space as Cultural Capital

The women’s landmark, which carries a lot of assumptions and meta phorical values, has created a multi-faceted relationship between the place, the local government, and its visitors. Receiving thousands of visitors every year, the park has become an important tourist attraction. In fact, alert to global competitive forces and domestic competitive pressures, the city government has aimed to develop Anping into a “Tourism Capital” and to maintain its appeal in the face of keen global competition. Being marketed as a unique destination that encompasses both elements of modernity and cultural tradition, Anping has often been recognized as an indelible part of Taiwanese culture and history, a place that gives people a sense of their roots in a rapidly globalizing era. The city government has made this restoration and revitalization of historical traditions a conscious program as a way of authenticating its identity. In order to expand this active marketing of the historical resources in recent years, Tainan City Government has promoted the landmark for cultural and recreational purposes. Capable of appealing to visitors with a variety of motivations and expectations, the park has become a compelling destination for leisure and enriched the stock of cultural/ historical capital.

To compete with other local popular Matsu destinations such as Da Jia Jen Lann Temple, the park is now able to cater to a range of different travel motives―both secular and religious. Religious culture is an important part of human culture as well as a tourism resource. For instance, Matsu culture is a particular tourism resource in Taiwan. According to Guo et al. (2006) and Shuo, Ryan, and Liu (2009), the tourism values of Matsu culture should be reconsidered. On the basis of the important value of Matsu culture in tourism, attention should be paid to the development of a Matsu cultural tour. An ancient female deity with modern significance, Matsu has become a common image in movements of both modern marketing and cultural revitalization within the greater Asia area. Being consumed in the modern setting, this female deity has penetrated very deeply into modern popular consciousness. The city government is obviously quite aware of the continuing appeal of the goddess as a resource of cultural tourism associated with Matsu. In recent years, while other local Matsu temples “compete for fame, political influence, worshippers, and lucrative donations,” the park has become a site of entertainment for local residents and tourists by offering regional concerts and national lantern festivals there (Yang, 2004, p. 223). Consequently, the young woman’s image successfully brings a closer relationship between the city and her visitors. While the incarnation of Lin is appropriated as a part of folk religion in other cities, Lin’s reconstructed image articulates a local response to the changes associated with the process of globalization in Anping. Combined with local resources, the locals create their own unique relationships to the park.

This modern reconstruction is also promoted as a heritage site and place of cultural importance. Increasingly, Anping has been marketed as the most traditional, heritage-laden, of Taiwan’s cities. Since the 1990s, it has emerged as one of Taiwan’s top tourism destinations. Anping’s tourism industry highlights a considerable stock of what are termed heritage properties. Other historical sites in Anping not only commemorate a selective past by paying homage to founding fathers and heroes, but also highlight the persistent masculinized themes such as militarism and the glorification of “Great Men” that run throughout the heritage industry. Not surprisingly, Lin Mor Niang appears as one of the female landmarks that have been endorsed by local government because she has been civilized and assimilated into the patriarchal, social and political culture. For those who strive to reclaim Anping’s lost heritage, its cultural and spiritual traditions, she is endowed with a specific mission--- promoting cultural pride and values in their region. In fact, descendants of early immigrants who safely crossed the Taiwan Straits to Anping often have felt a special attachment to the goddess. As P. Steven Sangren (1983) suggests, “Ma Tsu, after all, is closely associated with the history of earlier Chinese migration to Taiwan from Fukien and Kwantung…” (p. 16). Since she has become so deeply entrenched in popular consciousness, the icon has become a convenient way for many tourists and local inhabitants of the region to learn of the past. The image of Lin is thus easily assimilated to the discourse of heritage and refurbished to local cultural needs.

The Legend of Miss Jin

The other landmark, one also endorsed by the local government, is erected according to a similar cultural and political agenda. The legend of Miss Jin is well-known because of a popular Taiwanese melody---“ Song of Anping Reminiscence.” Written by Da-ru Chen and set to music by Hsu Shi in 1951, “Song of Anping Reminiscence” narrates a romance that took place between an Anping lady and a Dutch ship surgeon. In the 19th century, long after Zheng’s power had fallen off and Taiwan was controlled by the Qing dynasty, the quasi-legendary yet unverifiable story was said to have taken place in Anping. A young lady of mixed Taiwanese and Dutch blood and surnamed Miss Jin stood by the old Taiwan Canal wearing a red floral dress with her golden hair blowing in the wind, waiting for her lover. Alone and miserable, she wailed a song of lament over the repeated tragedy of unfulfilled love, for her father had left her mother decades before. According to the historians, the story was invented by Da-Ru Chen. But most local residents believed that it was true and that the descendants of the couple still live in the Anping area. No matter what the fact may be, it is quite reasonable to suppose the occurrence of such a story based on the historical development of Anping. Despite its popularity among Taiwanese, the song was censored because it was written in Holo during a time when the government was promoting Mandarin as the one and only national language.4 At the same time, its wistful recollection of the Dutch period undermined the official portrayal of Koxinga as a Chinese hero who expelled a foreign force and established the first Han Chinese government in Taiwan. Worst of all, the story, full of premarital sex, an illegitimate child, and a cross-racial relationship, was regarded as a cultural taboo in a morally conservative environment.

Constructing a City Image

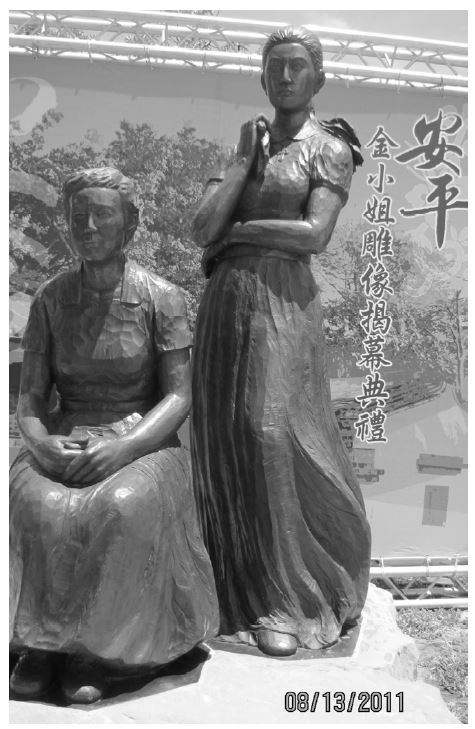

It was not until recently that Miss Jin was brought to more vivid life through a variety of literary and popular media that helped to make her the familiar figure that she is today. Surprisingly, the legend of Miss Jin continues to survive in official imagery of all sorts including a documentary, a painting, and a drama.5 The interaction of media, popular responses, and her legend--all generated around Miss Jin a particular charisma. Though people reinterpret various facets of her story, Miss Jin’s image has become synonymous with belonging to the city. It was around fifty years after the composition of the song and the story it narrated that Miss Jin became popular as the focal figure in a new founding myth of the city. Because her popularity occupies a space within the narratives of collective memory, the local government decided to use her as a city image to promote tourism. A year after Tainan was elevated as one of the five metropolitan cities in Taiwan, the local government decided to promote Tainan as a love city by holding a Tainan Chihsi Festival in 2011. One of the most important activities to promote Tainan as a love city during the festival was the unveiling of the statues of Miss Jin and her mother. On the day of the unveiling ceremony, both the mayor and the sculptor, who were invited to witness the symbol of love, not only emphasized that their love and hardships were memorialized as a part of the process of defining Anping as a city with a distinctive past, but also praised the strength and perseverance in Miss Jin and her mother (Chung, 2011). In this way, they promoted Miss Jin’s and her mother’s story as the embodiment of local cultural heritage.

While the mayor and the artist interpreted the set of statues as a tribute to the strength of love, the set of the statues, I would argue, is telling a more complex story. As some scholars already point out, memorials and monuments are political constructions, recalling and representing histories selectively, drawing popular attention to specific events and people and obliterating or obscuring others (Johnson, 1995, p. 63). More than a city image, the transformation of Miss Jin and her mother reflects a broader social and historical consciousness. Within a colonial and post-colonial context, public images of Miss Jin and her mother embody complex messages about race, nation, and gender. The statues, which articulate a myth of colonial encounter, suggest the inextricable interconnections between Western and Taiwanese culture. In the 17th century, Taiwan was occupied and ruled by Dutch colonizers who became a powerful presence in shaping the physical landscape of Anping. They built “Fort Zeelandia” (Old Fort of Anping) as the center of the Dutch trade with other Asian countries and as the center of governing the whole island of Taiwan. In 1858, the Qing Dynasty, after losing the Second Opium War, signed the Treaty of Tianjin with several Western nations. This and other subsequent treaties opened up Anping Harbor to foreign trade, allowed Christian missionary activity, and legalized the importation of opium. Foreign businessmen promptly set up operations in Anping. Frequently since then, Taiwan has witnessed considerable business between the Dutch and the locals in Anping. Moreover, Western culture started to influence finance, medical treatment, and religion in the city, playing a very important role in the development of modernization in Taiwan.

Indeed, the official representation of Miss Jin and her mother employs a powerful combination of written text and visual imagery to recreate the colonial heritage. There is a possibility that the parents of Miss Jin met while performing missionary work in Tainan, as the plaque next to the statues informs us that “they took a golden cross as a pledge of their love.” Still, Miss Jin’s true identity remains a mystery that drives historians and researchers to find the truth. Some say that her mother was abandoned by her Dutch lover and treated unjustly. Others speculate about what thwarted their marriage. One thing can be certain at this point-supposition about their unfulfilled love occupies a special place in the historical narrative of colonization. The lyrics attached to the plaque of the statues expose their destiny of misfortune. In the first section, Miss Jin, the golden-haired heroine of mixed-race parentage, waits for her foreign lover to return from a seafaring journey. There was a deep longing that her lover would return to Anping as she waited intently to hear the gong of his ship entering the harbor. In the meantime, she also remembered her Dutch father, who failed to keep his promise: “I’ve heard nothing from my dad for 20 years and I miss him, but I've nothing but the golden cross he left with my mom.” Miss Jin also laments how she suffered as an illegitimate child: “I know from my mom that I'm an illegitimate child and the more I think about it, the greater my sorrow.” Both the mother and daughter were indeed living out a life of extreme hardship. Obviously, their story, a tragic one that is very different from the official romanticized version, is therefore a reminder of the inequalities perpetuated by colonial foreign occupation and influences.

The image endorsed by the local authorities also suggests that Miss Jin and her mother, who once rebelled against established social mores, can gain their legitimacy only by being reconstructed as proper women who live up to the conventional image of Chinese women. Toward that end, it was the government that selected the statues’ designs and settled questions of style and location also dependent on the actions and visions of local businessman who controlled fundraising and donations. These men all played key roles in shaping the public faces of Miss Jin and her mother by using conventional elements of femininity to legitimize their position. Consequently, the statues, like that of Lin, functioned allegorically to tell a romantic story. Both mother and daughter still persisted in waiting for their love. Thus meeting traditional demands on women, their appearance and the drama they perform obey, “naturally” and simply, certain prescriptive metaphors that associate women with passivity and a sacrificial nature. Both mother and daughter earn the right to inspire traditionally chivalrous, even exaggerated, praise, in a way that a woman more contemporary in style and attitude fails to elicit.

A closer look at the life-size bronze statues shows that the artist uses a familiar and respectable trope of female personification to express an accepted view of goodness, hence their acceptability as official and public tributes to the women of Anping of the nineteenth century. Their strong and earnest facial expressions reveal their yearning for their lovers. The stoniness and metal hardness not only shows features of their strong personalities such as their resoluteness, strength, and determination, but also emphasizes traditional feminine virtues such as loyalty, devotion, and fidelity. The dark green color of the bronze statues further erases memories of Miss Jin as an illegitimate child with golden hair. In Monuments and Maidens: The Allegory of the Female Form (1985), Marina Warner points out that women, especially in statues, are portrayed not as individuals (as men are portrayed) but as fixed embodiments of virtues such as justice, mercy, temperance, and national aspirations. Ironically, local people do not notice that a young lady who once committed a sexual transgression has been made now to serve as love propaganda for the younger generation. Without this certificate of conformity granted by patriarchal representational practices, indeed, these women would be still considered irregular, anomalous, and dangerously deviant.

Conclusion

After the establishment of women’s landmarks such as statuary, they are never merely functional; instead, they will become artifacts that carry an additional symbolic charge. As one scholar has remarked, “monuments tend to use concrete visual forms to communicate moral meaning” (Auster, 1997, p. 221). The statues discussed not only have embodied cultural ideals, but they have also turned into a form of cultural capital. On the one hand, they preserve local cultural values. As a powerful and popular deity, Matsu serves as an important role model of religious and social behavior for Chinese (and, in the case of Matsu, Taiwanese) women (Cahill, 1986; Irwin, 1990; Mann, 1997; Paper, 1989). The statues serve as a new repository of indigenous values and moral sensibility---one that is centered on domesticity, filiality, and self-sacrifice. On the other hand, they have also become sites of struggle between local culture and the global tourist economy. While the installation of the statues is designed to appeal to the preferences of international tourists, it is the ideals of Chinese femininity, culture, religion, and myth that are consciously emphasized and marketed. Thus, configured by state and local cultural conceptions, both of these statues-Lin Mor Niang and Miss Jin-not only serve patriarchal interests, but also create the frames in which conventional gender roles are reinforced and constructed for public consumption.

In an era of fierce global competition for tourists, there is increasing recognition that women’s legends and stories provide valuable resources for tourism. In the case of Asian cities, particular forms of femininity are used increasingly to improve their images, stimulate urban development, and attract visitors. Annette Pritchard and Nigel J. Morgan (2010) assert that gendered and sexualized representations are typical descriptions of tourism destinations of the south and east (p. 128). In addition, Eileen Rose Walsh, in her analysis of Mosuo culture in China, notes that Mosuo women are the focus of the marketing of Mosuo territory. In other words, the image of the modern city depends on femininity to make its appeals and achieve its goals in the construction of spaces of tourism. Unfortunately, the discourse of city-building in its symbolic dimension entails representational practices that are deeply saturated with traditional gender concepts. Consequently, there is an urgent need to unravel some of the complex ways in which a gendered space is produced, and to identify a contrasting set of cultural meanings being communicated through these officially recognized images. By consciously appropriating female legends, entrepreneurial landscapes such as that at Anping serve as a means of reproducing and legitimizing patriarchal power and interest. As a strategy for urban growth and regeneration, such representations of women, though well intentioned, result in a cultural space that appears to embrace forms of feminine myth-making in an attempt to promote dominant values and local economies. Although new symbols of women are incorporated into the existing symbolic landscape of Anping, they nonetheless serve “the purpose of reproducing cultural norms and establishing the values of dominant groups across all of a society” (Cosgrove, 1989, p. 125).

Glossary

Harbor Historic Park.” It was part of “Challenging 2008: The Crucial Project of Domestic Development” proposed by the Executive Yuan in Taiwan.

Notes

2 Since 2002, the government of Tainan City has executed the “Project of National Anping

3 Both statues of Lin Mor Liang and Miss Jin and her mother were donated by Chi Mei Foundation, one of the major local businesses.

4 Holo, known as Hokkien, is considered a native language in Taiwan. Under the martial laws, the KMT government promoted Mandarin and banned the public use of Holo as part of a deliberate political repression.

5 A documentary on Miss Jin was issued in 2009. A painting about Miss Jin and her mother was also unveiled in the ceremony of 2011. There are also numerous films and local dramas about their story.

References

- Al Hindi, K. F., (2000), Women in geography in the 21st century. Introductory remarks: structure, agency, and women geographers in academia at the end of the long twentieth century, Professional Geographer, 52(4), p697-702.

-

Auster, M., (1997), Monument in a landscape: the question of ‘meaning’, Australian Geographer, 28(2), p219-227.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00049189708703194]

-

Azaryahu, M., (1996), The power of commemorative street names, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 14(3), p311-330.

[https://doi.org/10.1068/d140311]

- Basso, K. H., (1983), Western apache. In A. Ortiz (Ed.), Handbook of north American indians, Vol. 10: Southwest, p462-488, Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Basso, K. H., (1996), Wisdom sits in places: Landscape and language among the western apache, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press.

- Berg, L. D., & Kearns, R. A., (1996), Naming as norming; ‘race’, gender, and the identity politics of naming places in Aotearoa/New Zealnd, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 14(1), p99-122.

- Blunt, A., (1994), Reading authorship and authority: reading Mary Kingsley’s landscape descriptions. In A. Blunt & G. Rose (Eds.), Writing Women and Space: colonial and Postcolonial geographies, p51-72, London: Guildford Press.

-

Cahill, S., (1986), Performers and female Taoist adepts: Hsi Wang Mu as the patron deity of women in medieval China, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 106(1), p155-168.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/602369]

- Chiang, L., & Liu, Y., (2011), Feminist geography in Taiwan and Hong Kong, Gender, Place and Culture, 18(4), p557-569.

- Chung, T. S., (2011, August, 13), Anping song and the statue of Miss Jin: telling sad love stories, United Daily News, Retrieved September 28, 2011, from http://udn.com/NEWS/DOMESTIC/DOM1/6524871.shtml.

- Cosgrove, D., (1989), Geography is everywhere: Culture and symbolism in human landscape. In D. Gregory & R. Walford (Eds.), Horizons in human geography, p118-135, Hampshire: Macmillan.

-

Guo, Y., Kim, S. S., Timothy, D. J., & Wang, K. C., (2006), Tourism and reconciliation between mainland China and Taiwan, Tourism Management, 27, p997-1005.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2005.08.001]

- Herman, R. D. K., (1999), The aloha state: place names and the anti-conqest of Hawai’i, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 89(1), p76-102.

-

Irwin, L., (1990), Divinity and salvation: The great goddesses of China, Asian Folklore Studies, 49, p53-68.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/1177949]

-

Johnson, N., (1995), Cast in stone: Monuments, geography, and nationalism, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 13(1), p51-65.

[https://doi.org/10.1068/d130051]

- Kobayashi, A., (1994), Colouring the field: gender, ‘race’ and the politics of fieldwork, The Professional Geographer, 46(1), p73-80.

- Liu, W. S., (2000), The god statues of Taiwan, Taipei: Yishijia Publisher.

- Mann, S., (1997), Precious records: Women in China's long eighteenth century, Stanford, CA: University of Stanford Press.

- Maspero, H., (1981), Taoism and Chinese religion (F. A. Kierman Jr., Trans.), Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.

-

Mills, S., (1996), Gender and colonial space, Gender, Place and Culture, 3(2), p125-147.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/09663699650021855]

-

Myers, G. A., (1996), Naming and placing the other: Power and the urban landscape in Zanzibar, Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 87(3), p237-246.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9663.1998.tb01553.x]

- Nash, C., (1999), Irish place names: postcolonial locations, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 24(4), p457-480.

- Paper, J., (1989), The persistence of female deities in patriarchal China, Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, 6(1), p25-40.

-

Pritchard, A., Morgan, N. J., (2010), Constructing tourism landscapes-gender, sexuality and space, Tourism Geographies, 2(2), p115-139.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680050027851]

-

Radcliffe, S., (1996), Gendered nations: nostalgia, development and territory in Ecuador, Gender, Place and Culture, 3(1), p5-22.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/09663699650021918]

- Raju, S., (1993), Woman and gender in geography: An overview from south Asia. In J. H. Momsen & V. Kinnaird (Eds.), Different places, different voices: Gender and development in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, p77-79, London & New York: Routledge.

- Rey, S. W., (2001, October, 20), The establishment of Lin Mor Niang statue, United Daily News, p17.

-

Sangren, P. S., (1983), Female gender in Chinese religious symbols: Kuan Yin, Ma Tsu, and the ‘Eternal Mother’, Signs, 9(1), p4-25.

[https://doi.org/10.1086/494021]

-

Shuo, Y. S., Ryan, C., & Liu, G., (2009), Taoism, temples and tourists: The case of Mazu pilgrimage Tourism, Tourism Management, 30(4), p581-588.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.08.008]

- Tischer, J., (2012), Popular Mazu temples in Taiwan and the challenge of secular politics, Retrieved October 28, 2014 from http://sinica.academia.edu/Departments/Institute_of_Ethnology/Documents.

-

Valentine, G., (1993), (Hetero) sexing space: lesbian perceptions and experiences of everyday spaces, Environment and Planning D Society and Space, 11(4), p395-413.

[https://doi.org/10.1068/d110395]

- Warner, M., (1985), Monuments and maidens: The allegory of the female form, London: Vintage.

- Women and Geography Study Group, (1997), Feminist geographies: explorations in diversity and difference, Essex: Longman.

-

Yang, M., (2004), Goddess across the Taiwan Strait: Matrifocal ritual space, nation-state, and satellite television footprints, Public Culture, 16(2), p209-238.

[https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-16-2-209]