Does Demand for Women in the Agricultural Labor Force Reduce the Practice of Chhaupadi? Empirical Evidence from Tikapur, Nepal

Abstract

Chhaupadi is a form of menstrual taboo in Nepal, which banishes women from their usual residence and prohibits them from participating in family and social activities during menstruation as they are considered “impure.” Although the Supreme Court of Nepal outlawed Chhaupadi in 2005, it still exists, especially in the midwestern regions of Nepal. This study aims to examine whether there is an economic association between the practice of Chhaupadi and the demand for women in the agricultural labor force, thereby reducing discrimination against women. It uses the Nepal Tikapur Household Survey 2017 data (carried out using a face-to-face interview method) on the perception and practice of Chhaupadi in both urban and rural areas. The findings suggest that demand for women in the agricultural labor force has a significantly negative effect on the practice of Chhaupadi. This is supported by the fact that the Janajati caste, with the largest female participation in the family farm labor force, shows a considerably lower rate of this practice than other castes.

Keywords:

Chhaupadi, female labor force, menstruation, TikapurIntroduction

In Nepal, menstruating women and girls are considered impure and untouchable (Amatya, Ghimire, Callahan, Baral, & Poudel, 2018; Joshi, 2022). Chhaupadi is a form of menstrual taboo that separates girls and women from the rest of their families during menstruation. Increasing evidence has revealed that isolation from family and social exclusion result in depression, low self-esteem, and disempowerment. Furthermore, it is a risk factor for sexual violence, attacks by wild animals, and even death (Kadariya & Aro, 2015; Gautam, 2017). The Supreme Court of Nepal formally banned the practice of Chhaupadi in 2005, considering it a discriminatory practice that hinders fundamental human and women’s rights (UN Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator’s Office, 2011).

Despite being outlawed, Chhaupadi is still prevalent in some parts of Nepal, particularly in mid- and far-western regions. Some other regions also discriminate against menstruating women in other ways, such as not allowing them to enter temples. Most previous studies of this practice have addressed women’s health issues (Amatya et al., 2018; Karki & Khadka, 2019), female empowerment (Kunwar, 2013; Limbu, 2018), and human rights (Kadariya & Aro, 2015). This study analyzes the factors that affect the practice of Chhaupadi using an empirical method and examines whether there is an economic association between the practice of Chhaupadi and the demand for women in the agricultural labor force.

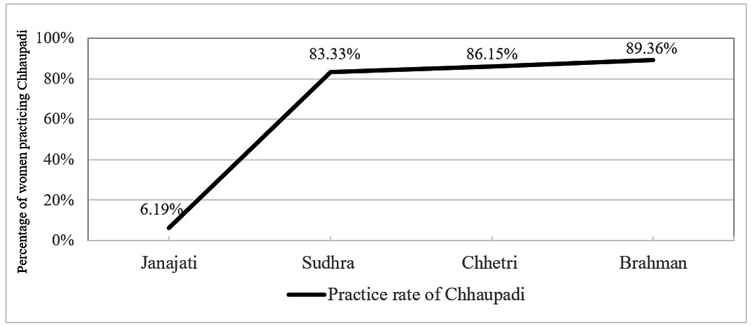

This study examines whether the practice of Chhaupadi is associated with the level of demand for women in the agricultural labor force. We used the Nepal Tikapur Household Survey Data 2017 dataset from the Institute for Poverty Alleviation and International Development at Yonsei University (Institute for Poverty Alleviation and International Development, 2017). At 6.19%, the Janajati caste had the lowest rate of practicing Chhaupadi, and also the highest proportion of women working on family farms. This is consistent with the fact that Janajati women must continue working in the field and at home as they normally do without any rest during menstruation (Rothchild & Piya, 2020). In addition, these data contain individuals’ perceptions of Chhaupadi, which provides a more profound foundation for this study.

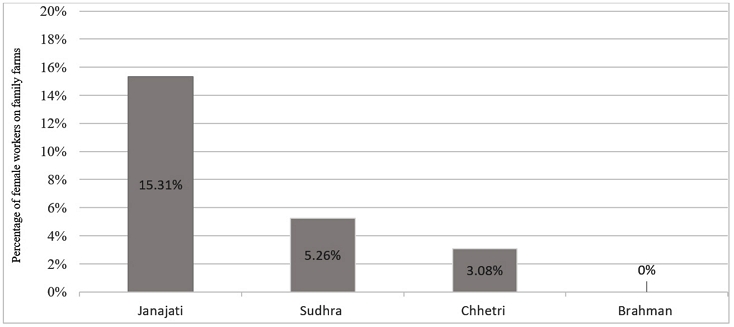

The main results can be briefly described as follows. First, through data analysis, we found that the proportion of women practicing Chhaupadi in the Janajati caste is significantly less than in other caste. In addition, considering that agriculture is the main source of household income for most people in the rural area, we analyzed the role of women in the agricultural labor force. This shows that 15.31% of Janajati households need three or more female laborers for the farm, which is much higher than is the case for other castes. Based on the above findings, we consider whether the demand for women in the agricultural labor force is linked to the rate at which Chhaupadi is practiced. Second, this study investigated women’s perceptions of Chhaupadi. The mean values indicate that, although many people do not favor implementing Chhaupadi, the influence of traditional, cultural, and religious factors is very ingrained. Notably, the trend of practicing Chhaupadi is declining across all castes, for various reasons. Third, the empirical analysis reveals that demand for women in the agricultural labor force could reduce the practice of Chhaupadi. For women who answered that agriculture was the primary source of their household income, it significantly negatively affected this practice.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the background to this study, while the dataset and model used in this study are described in Section 3. Section 4 presents the findings and the results of the empirical analysis, and the final section concludes the paper.

Research Background

Description of Chhaupadi

Women from the mid-western and far-western regions of Nepal, regions that lag in terms of overall development and gender equality, are victimized by social rituals, norms, and traditions due to the general lack of literacy and awareness of their social and legal rights (Kadariya & Aro, 2015). One of the traditional practices especially practiced in these regions is “Chhaupadi,” which bans menstruating women from their houses and forces them to live in cattle sheds or makeshift dwellings known as menstruation huts. According to Joshi (2022), approximately 70%–80% of women practice or are forced to practice Chhaupadi in western Nepal. This is originally a Hindu1 tradition, which relates to secretions associated with menstruation and childbirth (Kadariya & Aro, 2015; Stacke & Basu, 2017).

The term “Chhaupadi” is derived from local words used in the Raute dialect in the Achham district of Nepal, where “chhau” refers to menstruation and “padi” refers to women. The practice of Chhaupadi originates from the superstitious belief that menstruation causes women to be temporarily impure and they are therefore required to refrain from participating in normal daily activities (Kadariya & Aro, 2015).

Menstruating women and girls are isolated from their families and are forbidden from entering homes, kitchens, schools, and temples. The practice begins with the adolescent girl’s first menstrual cycle. During this time, she remains in a cattle shed or a makeshift dwelling made of mud and stones without windows or locks (Amgain, 2012) for up to 14 days. She will spend one week every month in the shed until she reaches menopause (Nepal Fertility Care Center, 2015).

The practice of Chhaupadi requires urgent public health attention, as it has several associated health impacts (Kadariya & Aro, 2015). Staying in an unhygienic shed during cold winters and hot summers (Kadariya & Aro, 2015) increases the likelihood of life-threatening health problems, such as diarrhea and dehydration, hypothermia, and reproductive and urinary tract infections (UN Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator’s Office, 2011). Women and girls also suffer from psychosocial problems, such as depression, low self-esteem, and disempowerment (Amatya et al., 2018). Their lives are constantly at risk due to fear of sexual abuse and assault at night, including attacks by wild animals and snake bites (Nepal Fertility Care Center, 2015).

Women’s Health

In Chhaupadi, women face various discriminatory practices (UN Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator’s Office, 2011). They cannot enter their homes. They have to spend their nights in tiny, unhealthy huts or cowsheds without windows, heat, electricity, or running water. Isolation from family members during menstruation harms women’s health because of the unhygienic environment, fear of sexual abuse, and assault at night, alongside the attack of wild animals and snake bites (Kunwar, 2013; Acharya, 2017; Nour, 2020). New mothers are also confined to cowsheds or huts (Kadariya & Aro, 2015). In addition, cowsheds or huts are not equipped with a mattress and warm blankets, forcing the women to sleep on a rug or a bare floor with sacks as coverings (Amatya et al., 2018).

Women are also barred from consuming milk products and meat because of the belief that giving such food to bleeding women would be punished by the gods, leading to food scarcity (Ranabhat, Kim, Choi, Aryal, Park, & Doh, 2015). This forces women to survive on basic food items, depriving them of nutrition. Moreover, they often engage in hard manual labor outdoors, such as digging, and collecting firewood and grasses, because they are not allowed to step into their houses during menstruation. This situation negatively impacts women’s health and makes them more vulnerable to various health problems including diarrhea, pneumonia, and respiratory diseases (UN Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator’s Office, 2011).

Chhaupadi harms women’s physical health and causes spiritual suffering (Joshi, 2022). Women are perceived as “impure,” and “unclean,” during the menstruation and postpartum periods (Jun & Jang, 2018). Such prejudices prevent women from participating in family activities, touching male family members, or even trees and plants. In some regions, women are not allowed to read, write, or touch books during their menstrual cycle because “Saraswati” (Goddess of Knowledge) will become angry (UN Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator’s Office, 2011). These prejudices make them feel insecure, guilty, humiliated, sad, and depressed, and their education is interrupted, increasing discrimination in the long term.

Chhaupadi and Human Rights Violations

Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that, “Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control.” Also, Article 2 states that, “Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, color, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.” The World Conference on Women’s Rights, the Beijing Declaration, and the Platform for Action declared that “Women and girls’ human rights are an inalienable, integral, and indivisible part of all human rights and fundamental freedom” (UN Women, 1995). Nepal adopted the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action in 1995.

The Vienna Declaration and its Program of Action calls for “the eradication of any conflict that may arise between women’s rights and the harmful effects of certain traditional or customary practices, cultural prejudices, and religious extremism’ (UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, 1993). Article 12 of the Interim Constitution of Nepal in 2007 ensures the right to equality. The rights to women’s reproductive health are secured in Article 20, while Article 29 (2) mentions that “no one shall be exploited in the name of any custom, tradition, and usage or any manner whatsoever.” Nour (2020) noted that the Nepal Supreme Court banned the practice of Chhaupadi in 2005 because of human rights violations. However, these international laws and Nepal’s internal laws do not effectively control this practice.

Kadariya and Aro (2015) discussed the practice of Chhaupadi in the mid-and far-western regions of Nepal. Their research uses multiple international laws to state the importance of human rights. Although the Government of Nepal outlawed Chhaupadi and condemned it as a breach of international laws and agreements, the tradition is still practiced in many rural areas of the mid-and far-western regions of Nepal. A positive change is happening, as girls and modern families have spoken out against the discriminatory practice of Chhaupadi in urban areas. Moreover, many civil society, non-governmental, community-based, and international organizations are working to reduce the practice of Chhaupadi by raising awareness in rural areas and educating women about menstrual hygiene (Amatya et al., 2018).

The Female Labor Force in Nepal

Table 1 outlines the occupational structure of the active population in rural and urban areas by gender, derived from the 2011 Nepal Population Census (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2014). This indicates that agriculture is by far the largest sector providing employment, especially in rural areas. A total of 79.18% of women in rural areas work in farming, while only 31.29% of those in urban areas do so. For jobs other than agriculture, forestry, and fishing, the percentage of men was higher than that of women. These trends indicate that many women are engaged in agriculture.

Methods

This study analyzes the relationship between the proportion of women in the labor force and the practice of Chhaupadi using survey data collected by the Institute for Poverty Alleviation and International Development (Institute for Poverty Alleviation and International Development, 2017). This survey targeted 413 households, comprising 1197 individuals in Pathariya2 and Tikapur3 in the Tikapur region. Individuals were interviewed separately. We examined the role of demand for female agricultural workers in reducing the practice of Chhaupadi, which was reported by approximately 220 women.

The dependent variable was whether women between 12 and 49 years of age practiced Chhaupadi. It is a binary variable: 1 for Women who practice Chhaupadi, and 0 for Women who do not practice Chhaupadi even when aged between 12 and 49.

Other variables were socioeconomic factors: age, marital status, education, health, and religion (the tradition of Chhaupadi derives from Hinduism). According to the 2011 National Population and Housing Census, Nepal’s major religion was Hinduism, accounting for 81.3% of the overall population (Government of Nepal, National Planning Commission Secretariat, 2012). Therefore, religion was included as a factor in this study. “Religion is important” was used as a variable to measure the degree of “Importance of religion in my life.” Another independent variable was “Agriculture is the main household income.” This was measured by the question: “Is agriculture the main source of household income? The options were 1 = “yes” and 0 = “no.” This study included four caste types: Sudhra, Janajati, Chhetri, and Brahman. Respondents’ places of residence were also controlled by allocating each to rural or urban groups.

Considering that the dependent variable is a binary variable (1: yes, 0: no), regression analysis was employed using a probit model to explore the impact of the independent variables on the practice of Chhaupadi. The equation used was as follows:

where RI is the level of “religion is important” for individual i, and AMI is the abbreviate of “Agriculture is the main household income” for individual i. SEF indicates social-economic factors, including age, marital status, education, health condition, and Hindu religion.

Findings

Demographic Characteristics

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics of the variables that include women aged between 12 and 49 years, which is the general age range for the occurrence of the menstrual cycle in women. (Ranabhat et al., 2015). The average age of women who practice Chhaupadi was 31.02 in rural and 29.58 in urban areas. The average duration of education for rural women was about 2.5 years less than that for urban women. Women’s health status was normal. In addition, the data showed that more than 90% of women practiced Hinduism. The mean value of the independent variable “religion is important” was very high, meaning that people thought religion was essential in their lives. Agricultural income was the primary household income for 44.64% of women in rural areas.

Figure 1 presents the rate at which Chhaupadi is practiced by caste. As can be seen from the line, for three of the castes the practice rate of Chhaupadi was higher than 83%, but the figure for Janajati women is a mere 6.19%, a considerable gap between them and the other castes. This contrast naturally leads us to examine the possible reasons for this.

Farming is one of the main occupations in the Janajati caste. Taking the occupation of the Janajati caste as an entry point, this study included “Agriculture is the main household income” in the regression analysis as female labor is also needed for family farms. Figure 2 shows the contribution of female labor to family farms, showing that the demand for women’s contribution to family farms among the Janajati caste was 15.31%, significantly higher than for the Sudhra, Chhetri, and Brahman castes.

Perspectives on the Practice of Chhaupadi

Table 3 presents the mean values of the perspectives of women aged 12–49 regarding Chhaupadi. Q01 suggests that most women think it is unnecessary to practice Chhaupadi, which is especially evident among Janajati. Chhetri are neutral, whereas Brahman are slightly biased in favor of Chhaupadi. Q02 shows that overall women’s understanding of Chhaupadi and traditional, cultural, and religious factors have the greatest influence on women’s practice of Chhaupadi. Women from all castes do not believe that the practices of Chhaupadi are more hygienic (Q03) or economically sensible (Q05). The truth is that women follow the practices of Chhaupadi because it is what people in their castes do (Q04). However, there may be other reasons that lead them to continue this practice. Nowadays, even though women know why menstruation occurs, they continue to practice Chhaupadi (Q07). Most women make sanitary pads and other menstrual products themselves, especially among the Janajati; 90% of women say that the necessary items are homemade (Q08).

Overall, although many people do not favor Chhaupadi, the influence of traditional, cultural, and religious factors is long ingrained. However, the decline in the trend of practicing Chhaupadi for all castes, for various reasons, is notable (Q06).

Main Results

Table 4 presents the differences in Chhaupadi practices based on perceptions of religion, whether agriculture is the main source of income, and in the context of different socioeconomic factors. Table 4 shows four models. Model 1 shows that castes are significantly affected by Chhaupadi. It illustrates that, compared with the Janajati caste, females from other castes (Sudhra, Chhetri, and Brahman) are more likely to have a positive perspective on the practice of Chhaupadi. Model 2 shows that both caste and religious factors significantly affect the practice of Chhaupadi. In addition, more women practice Chhaupadi in the Sudhra, Chhetri, and Brahman castes. Model 2 indicates that a strong belief that religion is essential in their lives is associated with more women practicing Chhaupadi. A stronger belief that religion is important makes women more obedient to religious teachings. Model 3 shows the effect of demand for women in the agricultural labor force on the practice of Chhaupadi. This is a negative coefficient, which means fewer women will practice Chhaupadi when agriculture is the main source of income. Model 4 considers all the variables together, religious factors also had a significant impact on Chhaupadi practices. The “Agriculture is the main household income” factor also remains the same as in Model 3.

To summarize, the empirical analysis indicates that fewer women practice Chhaupadi when agriculture is the main source of household income. While the influence of religion on the practice of Chhaupadi is deeply ingrained, there is a positive effect when more female agricultural laborers are needed or when women perceive agriculture to be their main household income.

Rural and Urban Areas

Table 5 presents the marginal effect of each factor that affects the practice of Chhaupadi in rural and urban areas, respectively. We can see that all castes show a positive and significant impact on the practice. However, we can see that the Chhaupadi implementation rate for Sudhra, Chhetri, and Brahman relative to Janajati is almost twice as high in rural as in urban areas. The influence of religion on the practice of Chhaupadi is not significant in rural areas but is significant in the cities.

In urban areas, the “agriculture is the main household income” factor shows a negative result, but this is not significant. Arable land is less available in urban than in rural areas and the limited available data produces insignificant results.

Overall, rural areas are mainly agricultural and need the support of a large female labor force. For Janajati women in particular, farm work is not interrupted during menstruation: the percentage of Janajati women practicing Chhaupadi is much different from that of the women of other castes. Even though religion is important to them, its influence is not significant in rural areas, since women are necessary for the labor force. In contrast, the burden of farm work for urbanites is relatively light, and the influence of religion is very deep, which could narrow the gap between Janajati and other castes in the frequency of practicing Chhaupadi.

Conclusion

This study examines the practice of Chhaupadi from the perspective of demand for female agricultural labor in Tikapur, Nepal. The results show that the Janajati caste has a very low percentage of practicing Chhaupadi compared with other castes, even though more than 90% of women in the Janajati caste are Hindus. The demand for women in the agricultural labor force among the Janajati caste is significantly higher than that in the other castes. Meanwhile, regarding women’s perceptions of different aspects of Chhaupadi, most women, especially those in the Janajati caste, think it is not necessary to practice Chhaupadi, but traditional, cultural, and religious factors have a greater impact on them. This is an important reason why some women practice Chhaupadi. Finally, it is shown that greater demand for women in the agricultural labor force could reduce the practice of Chhaupadi, thereby reducing unnecessary physical and psychological harm to women.

This study expands on the understanding of previous research of the factors influencing the practice of Chhaupadi, with a new perspective on the effect of demand for women in the labor force. Indeed, a female labor force is needed throughout society and such an increase will naturally decrease the practice of Chhaupadi. Additionally, the study highlights the impact of women in the labor force on other customs and cultural practices.

Acknowledgments

For the first author, this work was supported (in part) by the Yonsei University Research Fund (Post Doc. Researcher Supporting Program) from March 1 to August 31, 2022 (project no.: 2022-12-0028).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Notes

References

- Acharya, B. K. (2017). A study of Chhaupadi Pratha (Menstrual Discrimination) in Nepal: Its causes and consequences (master’s thesis). Ewha Womans University, Seoul.

-

Amatya, P., Ghimire, S., Callahan, K. E., Baral, B. K., & Poudel, K. C. (2018). Practice and lived experience of menstrual exiles (Chhaupadi) among adolescent girls in far-western Nepal. PLOS ONE, 13(12), e0208260-e0208260.

[https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208260]

- Amgain, B. (2012). Social dimension of Chhaupadi system: A study from Achham district, far west Nepal. Kathmandu, Nepal: Social Inclusion Research Fund (SIRF).

- Central Bureau of Statistics (2014). Population Monograph of Nepal. Kathmandu, Nepal. Retrieved Au-gust 23, 2022, from https://nepal.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/Population%20Monograph%20V02.pdf

- Gautam, Y. (2017). Chhaupadi: a menstrual taboo in far western Nepal. Reason, 148, 80-0.

- Government of Nepal, National Planning Commission Secretariat (2012). National population and hous-ing census, 2011. Kathmandu, Nepal: Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved August 23, 2022, fr-om https://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/sources/census/wphc/Nepal/Nepal-Census-2011-Vol1.pdf

- Institute for Poverty Alleviation and International Development. (2017). IPAID’s capability data series: Tikapur, Nepal. Unpublished raw data.

- International Labour Organization (2012). International Standard Classification of Occupations Structur-e. Volume 1. Group Definitions And Correspondence Tables. Geneva. Retrieved August 23, 202-2, from https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@dcomm/@publ/documents/publication/wcms_172572.pdf

-

Joshi, S. (2022). Chhaupadi practice in Nepal: A literature review. World Medical & Health Policy, 14(1), 121–137.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/wmh3.491]

-

Jun, M., & Jang, I. (2018). The role of social capital in shaping policy non-compliance for chhaupadi practice in Nepal. Asian Women, 34(3), 47-70.

[https://doi.org/10.14431/aw.2018.09.34.3.47]

-

Kadariya, S., & Aro, A. R. (2015). Chhaupadi practice in Nepal–analysis of ethical aspects. Medicolegal and Bioethics, 5, 53–58.

[https://doi.org/10.2147/MB.S83825]

-

Karki, T. B., & Khadka, K. (2019). False belief and harmful cultural practices of Chhaupadi system in Nepal. Nepal Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, 2(3), 19–24.

[https://doi.org/10.3126/njmr.v2i3.26971]

-

Kunwar, P. (2013). Coming out of the traditional trap. Asian Journal of Women’s Studies, 19(4), 164–172.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/12259276.2013.11666170]

- Limbu, A. (2018). Impact of Innovative Menstrual Technology and Awareness on Female Empowerment Outcomes in Rural Nepal (Unpublished master’s thesis, #1155). University of San Francisco, CA. Retrieved August 23, 2022, from https://repository.usfca.edu/thes/1155

- Nepal Fertility Care Center (2015). Assessment study on Chhaupadi in Nepal: Towards a harm reduction strategy. Kathmandu, Nepal: Nepal Fertility Care Center. Retrieved August 23, 2022, from https://web.archive.org/web/20181222210931/http://nhsp.org.np/wp-content/uploads/formidable/7/Chhaupadi-FINAL.pdf

-

Nour, N. M. (2020). Menstrual huts: A health and human rights violation. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 136(1), 1–2.

[https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000003969]

-

Ranabhat, C., Kim, C. B., Choi, E. H., Aryal, A., Park, M. B., & Doh, Y. A. (2015). Chhaupadi culture and reproductive health of women in Nepal. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health, 27(7), 785–795.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/1010539515602743]

-

Rothchild, J., & Piya, P. S. (2020). Rituals, Taboos, and Seclusion: Life stories of Women Navigating Culture and Pushing for Change in Nepal. In C. Bobel, I. T. Winkler, B. Fahs, K. A. Hasson, E. A. Kissling, & T. A. Roberts (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies, 915–929

[https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-0614-7_66]

- Stacke, S., & Basu, P. (2017). The risky lives of women sent into exile–for menstruating. National Geographic, March 10. Retrieved August 23, 2022, from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/photography/article/menstruation-rituals-nepal

- UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (1993). Vienna declaration and program of action. Geneva: OHCHR. Retrieved August 23, 2022, fromhttps://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/vienna-declaration-and-programme-action

- UN Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator’s Office (2011). Field Bulletin: Chaupadi in the Far-West. Kathmandu, Nepal: United Nations RCHC Office. Retrieved August 23, 2022, from https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/Water/ContributionsStigma/others/field_bulletin_-_issue1_april_2011_-_chaupadi_in_far-west.pdf

- UN Women (1995). Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action-Beijing+ 5 Political Declaration and O-utcome. New York, NY: UN Women. Retrieved August 23, 2022, from https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2015/01/beijing-declaration

Biographical Note: Hongyu Wan is a post-doctoral researcher at Yonsei University, South Korea. E-mail: whyhongyu61@naver.com

Biographical Note: YoungRok Kim (corresponding author) is a postdoctoral researcher at the Kansai University. E-mail: econ.maple@gmail.com