Conceptualizing the Issues Related to the Mob Lynching of Women in India: A Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of Media Corpus and Discourse

National Institute of Technology, Raipur, India National Institute of Technology, Raipur, India National Institute of Technology, Raipur, IndiaAbstract

In certain parts of India, women are branded as witches, suffer mob humiliation and, at times, are lynched. To understand this phenomenon, this study engages in a critical analysis of witch-hunt discourse. It investigates the discursive layers of news narratives on mob violence executed against tribal women in Jharkhand state, India, where the tribal groups account for 27% of the total population. A corpus-based critical discourse analysis framework was applied to understand the collocational and concordance phenomena associated with gender violence in primitive communities. Our results reveal that the individual identities of the victims are underlined as social culprits, whereas the aggressors’ identities are assimilated into larger anonymous groups. Moreover, witch-hunt discourse revolves around superstition and suppresses alternative reasoning, such as the absence of healthcare facilities, gender power dynamics, and the role of state actors.

Keywords:

Witch-hunt, tribal women, media, lynching, actorsIntroduction

Recently, several attempts have been made to examine the sociocultural dynamics of witch-hunting, which is a widely prevalent form of self-proclaimed mob justice in many Asian societies, including the indigenous tribal societies of India (Chaudhuri, 2013; Damodaran, 2002; Sundar, 2001). Although print and electronic media have frequently reported incidents of witch-hunting, an analysis of the witch-hunt media discourse has been missing in scholarship (Behringer, 2016; Sinha, 2006; Xaxa, 2004). The recent rise of the witch-hunt phenomena in India has led to a discursive debate on the role of media discourse in constructing the thematic identity of the practice among tribal communities. Available studies on witch-related media discourse have primarily focused on the creating and maintaining an image of female magicians practicing witchcraft, an image that is then projected through electronic media and films (Berger & Ezzy, 2009; Rowe & Cavender, 2017). However, very few studies have critically analyzed the written media corpus from the perspective of addressing the role of actors and the factors involved in the witch-hunt discourse (Adinkrah, 2011; Englund, 2007). Indeed, how the news media treat the incidents of witch-hunting prevalent in South Asia has escaped scholarly attention, especially in the multicultural and traditional setup of Indian society. Accordingly, the current study analyzes media discourses that may project superstition as the cause of witch-hunts, while suppressing the role of villagers in conducting mob crimes against women. Further, the study explains how the media individuates and isolates victims from larger groups based on the fact that they are women.

Previous studies have identified and focused on victims of witch-hunts, mainly teenagers, widows, and abandoned or unmarried women. These studies emphasized misfortune in villages or among communities as the leading cause of witch-hunting. For instance, across tribal cultures, witches are believed to have access to supernatural powers that can harm individuals, families, or the entire community (Adeney, 2020). Consequently, these superstitions provide a sound basis for people undergoing a loss or experiencing a misfortune to act violently against weaker classes or the less powerful gender (Sharma, 2018). The main cause of such superstitions, however, could be the scarcity of food and inadequate healthcare facilities in tribal areas (Narain, 2019). Furthermore, the hegemonic discourse of the structural-mainstream projects tribals as submerged in superstition and blind faith, carrying stupidity and irrationality with them. Such a discourse omits socio-political exploitative and discriminative factors (such as malnutrition, food insecurity, and access to medical facilities), and claims that tribals are themselves responsible for their unfortunate conditions (Kamat, 2002). Thus, this study was motivated by the dialectics of witch-hunt discourse, and proposes the absence of healthcare facilities as the major cause, as opposed to blaming belief in black magic and superstition.

Scholars link the universal existence of misogyny and sexism to analyze the gendered aspects of a witch-hunt (Behringer, 2016; Sinha, 2006). They also view these mob actions in terms of the activation and maintenance of group categories, boundaries, identities, and the roles played by mediating organizations in society (Smångs, 2016). For Chaudhuri (2013), women are mainly targeted for two reasons. First, witches are generally portrayed as women. Second, women hold a lower socio-political and ritual position than men. According to other scholars, witch-hunting has been a violent expression of resentment by primitive communities resulting from economic and political dissatisfaction. During such processes, the weaker gender becomes an easy scapegoat for the release of anger (McBride, 2019).

Capitalism was another development that resulted in difficult living conditions for non-mainstream cultures, and promoted inhuman social practices such as witch-hunting (Behringer, 2016; Reed, 2015). Thus, witch-hunting has emerged as a new phenomenon in many modern societies in response to globalization, which has caused socioeconomic stress among native populations because of the exploitation of local resources (Farrell, 2019). This is also evident in the tribal regions of India, where much of the indigenous population lives in displacement settings, having lost control over land and forest due to mining and industrial projects (Behera, 2019).

A strong belief in witchcraft is prevalent in Indian states such as Jharkhand, Odisha, and Chhattisgarh, where 26.5% of the population belongs to tribes. Among them, all actions, whether good or bad, are attributed to factors such as the earth, spirits, or human motivations (Sundar, 2001) and this strong faith in supernatural powers provokes mob action against the weak, here and in many parts of the country (Hund, 2004). Interestingly, when a community faces an unusual natural calamity or an untimely accidental event, the possibility of women being accused as part of a witch-hunt increases (Macdonald, 2015). Consequently, over the years, witch-hunt-related violence has been culturally accepted and has become a social norm in India (Roy, 1998).

The undercurrent of superstition in India extends cultural beliefs from the collective to the individual’s worldview, and these have also periodically been both reinforced and countered by political actors (Chakrabarty, 2008). For instance, the famous debate between Mahatma Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore after the deadly Bihar earthquake in 1934 highlights how superstitions were rigidly internalized and strengthened by the social structure, powerful actors, and their public discourse (Raza, 2018). Gandhi saw the earthquake as a form of divine punishment for the sins of untouchability that existed in India, which in turn worried Tagore, who believed that Gandhi was pushing India back to the Middle Ages (Puri, 2015).

With these undercurrents, bali (animal sacrifice), havan (fire-chanting), and other rituals are still evident in Indian life contributing to the epistemic production and maintenance of superstitions and spirit-related activities (Chakrabarty, 2008). Thus, witch-hunts are hidden within local social power dynamics as well as powers involving organized actors such as the state and religion (Magliocco, 2020). As witch-hunting cannot be attributed to any one particular factor, the subject has to be explored as an intellectual, legal, socio-psychological, political, and medical phenomenon (Brooke & Ojo, 2020). In this sense, the analysis of the print media discourse aims to provide different clues for establishing an understanding of the witch-hunt phenomena. Interestingly, in the Indian context, there are hardly any studies that discuss the sociopolitical and cultural motives leading to the mob persecution of women. This research gap therefore provides a motivational background for conducting a Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) of witch-hunts in an Indian context.

The Current Investigation

The current study aims to critically analyze the media discourse on witch-hunting to conceptualize the issues related to the mob lynching of women in India. Witch-hunt news stories suggest that it is largely women who are victims of mob or group crimes (Harris, 2018). In this context, a frenzied mob is considered a powerful social actor that wields power to harass women (Pelican, 2016). Mainstream media, which is itself a powerful political actor, often reports such incidents (Fawzi, 2018). Therefore, in this context, CDA, which is a method of studying social problems by applying the discourse-semiotic approach, enables a researcher to understand the layers of witch-hunt phenomena that have been narrated, reported, and projected in print media. Moreover, the feminist standpoint considers language a tool to investigate the gender biases involved in witch-hunting. Since language has the power to challenge dominant beliefs and ideas, its strategic use can support or hinder social reforms (McConnell-Ginet, 2014). The present study explores the print media discourse on witch-hunting to address the following research questions (RQ):

- RQ1: How do media reports foreground, background, or omit the actors and factors in the witch-hunt discourse while controlling and representing the different lexical markers?

- RQ2: How does the media discourse on witch-hunting project group affiliation and identity and how does it refer to victims and perpetrators?

To answer these research questions, the present study tests the following hypotheses (H), which explain the roles of different actors and factors involved in constructing the media’s witch-hunt discourse.

- H1: The media discourse on witch-hunts may represent culprits as members of a larger and anonymous group of society, but may individuate and isolate the victims from larger groups in terms of their being women.

- H2: The media discourse may reinstate superstition as the main cause of witch-hunts and suppress the role of government actors in mob crimes against women.

Data and Methods

Corpus Compilation

To create a corpus of witch-hunting news, all such reports published in the Hindustan Times (HT) and Times of India (ToI) between January 2015 and June 2019 were collected. We selected the Indian state of Jharkhand for the current study because, according to the National Crime Record Bureau (2018), it reports the highest number of cases of witch-hunts. The ToI and HT (both English-language newspapers) were selected because they have the highest circulation and readership in Jharkhand according to the Audit Bureau of Circulation (2018) and the Indian Readership Survey (2019). A purposive systematic sampling technique was used for maximum accuracy in the representation of the samples. We searched for news items related to witch-hunt incidents in the online editions of both newspapers. News items containing any of the keywords “witch-hunt,” “witch-hunts,” or “witch-hunting,” either in sub-headings or main headings, were downloaded to collect more precise and accurate data. A total of 262 witch-hunt news items were downloaded from the newspapers’ official websites. From these, we selected 224 news stories as reported by the ToI (N=121) and HT (103). After repeated items were removed, the final compiled corpus, consisted of 152,895 tokens and 10,030 types (Table 1).

Data Analysis

The corpus was analyzed by adopting corpus-assisted critical discourse analytic methods that involved both quantitative and qualitative analyses. The #LacsBox-5.1.2 computer program was used for quantitative data extraction. This software extracts key linguistic markers from a corpus and provides mutual information (MI) scores for lexical collocates. Thus, inferred quantitative trends from the corpus were analyzed qualitatively at the second level by employing the CDA framework. We performed corpus analysis in the following four stages to eliminate inferential errors: (1) identification of key lexicons, (ii) locating the position of key lexical markers in the text, (iii) calculation of the collocates’ mutual information scores, and (iv) analyzing discursive strategies using van Leeuwen’s framework.

Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) computer software was used to identify key lexical markers. This software processes the corpus and categorizes the lexicons into various categories, such as lexico-grammatical, lexico-semantic, and lexico-temporal (Pennebaker, Boyd, Jordan, & Blackburn, 2015). After observing the high mean frequencies of negative and positive emotional words, adjectives, gender pronouns, and groups denoting lexical markers, the corpus was further processed using the #LancsBox program to determine the functional association of those lexicons with the central markers: witch, witch-hunt, and witch-hunting. Lam (2018) indicated that lexical words are the main carriers of information that contributes to semantic construction and communication. Therefore, in the process of lexical selection, we analyzed content words such as nouns, verbs, adverbs, and adjectives, which denote lexical meaning referring to actors or actions. Though pronouns are classified as functions or grammatical words, they stand for nouns referring to genders and groups. Therefore, the current study included pronouns that represented gender (he, she, his, her) and group (we, they) actors relating to the witch-hunt discourse. #LancsBox software developed by Lancaster University traces the collocational and concordance trends in a corpus (Brezina, 2018). Thus, high-frequency collocates were identified in #LancsBox to trace their habitual co-occurrence with the central markers to calculate the MI scores.

Five-left and right-collocating lexicons were recognized as the central position of “witch,” for further discursive analysis under the CDA framework. Though several frameworks (for example, Discourse Historical Approach, Discourse Cognitive Approach, or Fairclough’s Discursive Layers) can be used in CDA, the current study combines the quantitative method of corpus linguistics and the qualitative model of van Leeuwen’s framework. The Van Leeuwen (2008) CDA framework gives an idea of how social actors are represented in discursive events. In the current study, we selected four major parameters to analyze discourse. First, the exclusion criteria included (a) the total or radical exclusion or the suppression of specific social actors that leave no traces of omission, and (b) partial suppression, that is, backgrounding of social actors. Second, the allocation of roles and rearrangement of social relations define whether social actors have either an active or a passive role. Third, assimilation of the individual identity of social actors is represented either individually or collectively. Fourth, social actors may perform single or multiple social roles.

Results

The Left 5 Collocates from the Central Position of “Witch”

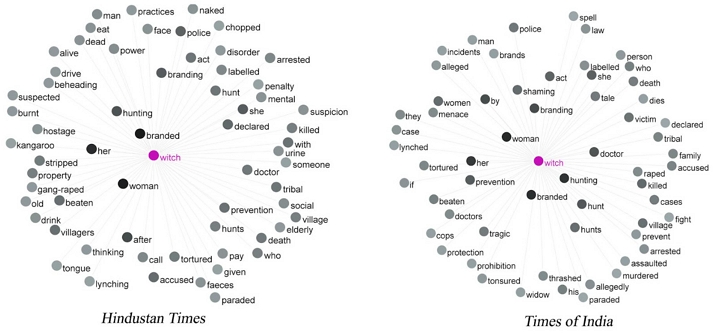

The collective corpus of material drawn from both newspapers, excluding articles and auxiliaries, showed high mutual informative (MI) patterns of gender and accusative markers in the left 5 (L-5), and action- or result-denoting lexical markers in the right-5 (R-5). The left-5 collocates like “branded,” “declared,” and “labeled” imply the strategic construction of identity around gendered nouns like “witch” and “woman” and pronouns like “she” and “her”. Two female actors are frequently visible in L-5, i.e., “woman” and “she,” which are associated with the possessive pronoun “her.” This indicates that, although in the witch-hunt media discourse, the victims are foregrounded as the main actors in the same discursive events, the subjective noun or pronoun of the violent actions of the culprit is always placed in the background events. Unfortunately, the resultant feature of the adjective “tragic” and the action verb “raped” also habitually co-occurred with high MI scores in L-5 which ranged within the central position of “witch.” Moreover, the negative semantic lexical-markers “tragic” and “raped” are associated with female actors. The nominal word “prevention,” in the sense of “banning of intention,” is frequently observed in the L-5 range as a prefix to the legal phrase “prevention act.” A specific community referral noun, “tribal,” which is categorized as an indigenous human group, also appeared frequently with “witch” as an L-5 collocate. This infers that witch-hunt phenomena are significantly linked with tribal or indigenous communities in relation to women.

- Statements:

- (i) The witch-hunt media discourse foregrounds female actors more frequently as victims, but it simultaneously backgrounds the performing actors as powerful male aggressors.

- (ii) The low visibility of the markers signifies that the actors responsible for the witch-hunt discourse function to suppress or omit aggressors. The discourse also shows an imbalance between the high visibility of victims and the low visibility of perpetrators. Suppression or omission of aggressors exempts perpetrators at the discursive level because they are invisible or less visible in the discourse.

The Right 5 Collocates from the Central Position of “Witch”

The collective corpus of material drawn from both newspapers, excluding articles and auxiliaries, showed a useful pattern of past continuous forms of action verbs in the R-5 range. The negative verbs referring to past actions like “beaten,” “tortured,” “killed,” and “accused” were found more frequently in association with the right periphery of the central word “witch.” The lexico-grammatical female subjects like “woman,” she,” and “her,” which were followed by the past tense of negative verbs such as “beaten,” “tortured,” “killed,” and “accused” and the continuous forms of the verbs “hunting” and “shaming” defined the association of women with the middle position of “witch” in the range of R-5. Out of 10 high-scoring collocates in R-5, the seven terms “hunting,” “shaming,” “beaten,” “tortured,” “killed,” “accused” and “death” were categorized as negative words in the LIWC semantic calculation. The high MI score of the noun “death” was also associated with “witch.” This implies that death is closely linked to witch-hunting. The functional category of the word “by” also frequently co-occurred with “witch” in R-5 which assigns the actions performed by “whom” (performing actors of violence). However, there are no other actors similar to the female gender markers that have habitually been observed and which co-occurred in either L-5 or R-5 from the centrally located “witch.” This infers that, in witch-hunt phenomena, the main actors who perform violent actions are purposefully either backgrounded or omitted from the discourse. The law denoted by the term “act” also provided a high MI score. The term has been used in a legal phrase as a suffix complementary to the phrase “prevention,” and it appeared in the L-5 range. The professional identity of the actor i.e., “doctor,” frequently co-occurred in the R-5 from the referential position of “witch.” This reveals that treatment and health-related issues are highly associated with incidents of witch-hunting.

- Statements:

- (i) The aggressive markers along with the action-denoting verbs “tortured,” “killed,” “accused,” and “died” are highly associated with the female actors “witch,” “woman,” and “she”.

- (ii) The functional preposition “by” frequently co-occurred with “witch” in R-5, but there is no high MI-scoring individual or group identity that appeared concerning “witch,” suggesting the actors involved in the action are either backgrounded or omitted from the discourse.

Comparison of Newspaper Discourses

Out of 10 high-scoring L-5 collocates from the referential position of “witch,” excluding articles and auxiliaries, five lexical markers—“branded,” “her,” “prevention,” “she,” and “labeled”—were observed in both newspapers. The third singular feminine pronoun “she” and its possessive counterpart “her” denote the acts of identity imposition “branded” and “labeled” in the L-5 range of discourse. The intentional representation of the noun “prevention” is also commonly associated with “witch-hunt” (Table 2). Lexical markers like “declared,” “power,” “thinking,” “hostage,” and “out” in HT and “woman,” “tragic,” “raped,” “victim,” and “tortured” are uniquely presented in ToI news narratives in the L-5 range from the centrally located “witch.” The L-5 collocates “thinking,” “declared,” “hostage,” and “out” observed in the HT media texts denote a socio-semantic sequence of action. Similarly, the female actor “woman” is significantly associated with the adjective “tragic,” the noun “victim,” and the verbs “raped” and “tortured.” In ToI news reports, most of these negative verbs habitually co-occurred in the L-5 periphery from “witch.”

In the R-5 range, two action-denoting verbs, “hunting” and “beaten,” along with the legal term “act” and the word group signifying the word “village” were commonly used in both newspapers. In the HT corpus, “tortured” and “stripped,” two lexical markers denoting action, the functional word “by,” the word “pay” referring to a penalty, and one term referring to psychological state, “mental,” were high-scoring MI collocates in R-5 from the referential position of “witch” (Figure 1). The psycho-social punishments denoted by the meanings of the terms “shaming” and “violence” were strongly associated with “killed” and “thrashed.” The ultimate consequence of violence, “dies,” consistently co-occurred with the R-5 range of ToI news reports. However, in both the newspapers, the groups denoting the actors involved in the action, “village” and “villagers,” are often presented in the R-5 range from the referential position of “witch.”

- Statement:

- (i) Both the HT and ToI show a similar habitual association of lexical markers in the L-5 and R-5 range from the referential position of “witch.”

- (ii) In contrast, the two newspapers use different negative synonyms and verbal forms attributed to the actions of group actors like “village” and “villagers” when foregrounding aggressive, violent, and lethal actions that are performed against women.

Legitimizing the Fact that Witches Exist

- (1) Witchcraft is a major social evil spread across the tribal belts of Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, West Bengal and the northeast (HT, Aug 8, 2015).

- (2) 60-year-old witch killed in Khunti (Headline) (ToI, Aug 14, 2015).

- (3) A 48-year-old man hacked to death four members of a family in Jharkhand’s East Singhbhum on Wednesday, in what police said was a revenge attack as one of the victims’ brothers had branded his wife a witch before she was killed (HT, Jan 21, 2016).

- (4) 30-year-old beaten up for being a witch (Headline) (ToI, Jan 6, 2016).

- (5) In modern India over 100 witches are killed every year (Headline) (ToI, Nov 7, 2016).

- (6) Their youngest brother’s new-born child had died recently. Both accused believed that Phulmani was a witch and hence, the scourge behind the problems (HT, Mar 17, 2019).

News narratives openly represent cultural viewpoints as superior and inferior and convict the tribal as the main culprits in witchcraft (Example 1). They do not criticize witch-hunts, but consider witchcraft a major social evil. Practices such as witchcraft, sorcery, and the occult have been practiced to heal members of indigenous tribes. Consequently, news construction has in many instances been significantly influenced by patriarchal belief systems. In examples 2, 4, and 5, news headlines project a declarative tag that “witches exist” and the accompanying narratives have a sexist tone. Using the term “witch” without the inclusion of “accused,” the words “alleged” and “branded” legitimize the existence of witches. Example 3 indicates a personal and familial vendetta, which is an important factor instigating incidents of witch-hunting. This finding supports the earlier observation that poverty and malnutrition lead to mental disorders, which consequently affect proper functioning of the brain. The high rate of food insecurity and absence of standard free health services force resource-deprived villagers to search for an alternative interpretation of their misfortunes (Example 6). However, the untimely death of villagers increases the chances of someone being branded a witch, leading to violent assaults on or even the lynching of women.

Overemphasis on the Role of Superstition

- (7) The help of NGOs in educating people on witchcraft-related superstition is being taken. SPs of all districts of the state have been instructed to launch massive campaign to eradicate witchcraft-related superstition and incidents," he stated (ToI, Mar 16, 2016).

- (8) Combating superstition has been one of the major hurdles for the tribal state, where practices of witch-hunting, tonsuring and animal sacrifices for a better harvest and also nude processions for rains are prevalent (HT, Apr 19, 2016)

- (9) The atmosphere in the village is extremely tense. People are so superstitious that they do not want to listen to any argument. Jharkhand women’s commission chairperson Mahua Manjhi said superstition is deep-rooted in the village even though it is situated next to the state capital (ToI, Aug 9, 2015).

- (10) Apart from the superstition (angle), we are probing whether the anti-alcohol movement led to the death of these women," said the superintendent of police (rural) Raj Kumar Lakra (HT, Aug 09, 2015).

In Example 7, the role of state actors (i.e., the government) has been omitted from the media discourse. It is not clear who instructed the Superintendent of Police (SP) to launch a campaign against witch-hunting. The organizational actors i.e., “NGOs,” and the state actor i.e., “SPs” have been allocated a role to combat a pre-determined and state-defined reason i.e., superstition. Furthermore, the news narratives overemphasize superstition among tribes as the main reason for witch-hunts and exclude other state-related factors from the discourse (Example 8). The strategic foregrounding of superstition is so intense that it overshadows the alternative factors responsible for witch-hunting. Further, the quote from the chairperson of the Women’s Commission functions as a discourse erasure relating to superstition (Example 9). However, Example 10 provides an alternative discursive scope for combating the witch-hunting phenomenon. State actor SP belonged to the tribal community. Therefore, he suggested a possible alternative angle, political tension at the gender level, probably under his cultural construct of the mainstream worldview.

Assimilation of Culprits’ Identity

- (11) The death of five children in the village within a span of six months had deepened the superstitious beliefs and suspicion of the villagers who said that the women had cast spells on them (HT, Aug 9, 2015).

- (12) The victims were allegedly beaten up by their relatives before they were tonsured and paraded through the village. Malti Devi, one of the accused who lived in Ranchi, said that she used to get sick whenever she came to the village (TOI, Feb 17, 2018).

- (13) The villagers have submitted a written confession to the police claiming responsibility for the killings (HT, Aug 2, 2018).

- (14) The victim, in her complaint with Jamuna police on Tuesday, said she was being regularly tortured by a section of villagers for the past 3 months. "We had discussed the issue with other villagers in the presence of Mukhiya and other panchayat representatives but none of them chose to help” (ToI, Nov 2, 2016).

- (15) The culprits were seen beating the elderly women with sticks in the presence of dozens of villagers, including women and children, who made no effort to come forward to help her (ToI, Nov 10, 2018).

Example 11 suggests a dilapidated health infrastructure that is directly linked to incidences of witch-hunting. Superstition rests on the inaccessibility of health treatment facilities and poverty-driven food insecurity, the latter of which results in malnutrition at the community level. Witch branding and hunting are usually performed with the accusation of access to black magical powers and amidst the prevalence of superstition. However, many witch-hunts also suggest hidden intentions of personal or familial revenge (Example 12). Example 13 shows the process of assimilating identities into a single collective actor—villagers. The role has been allocated to village organizations in general without any differentiation of identities such as male, female, children, victim’s family, or culprits’ names. This also indicates that witch-hunts have successfully achieved the status of a cultural sanction as well as legitimacy at the cultural institutional level. Further, Example 14 reveals that villagers, as collective organized social actors, are problematic when a victim identifies them as causing her physical harm. In this instance, the muteness and non-action of the panchayat (functional institutions of grassroots governance) favor organized and collective action against the witch-hunt victim. This observation is important for establishing an understanding of how the witch-hunt phenomenon is deeply ingrained in socio-political and power-wielding actors who selectively target specific women. Further, the existence of powerful structure-based systematic violence against women counters the prevalent myth that the tribal women of Jharkhand enjoy greater socio-political rights, autonomy, and respect, as opposed to mainstream women (Mitra, 2008). It also provides indications of how gendered violence functions in subaltern societies. Example 15 confirms that the perpetrators of crimes are identifiable at the group level, but their specific individual identities have been assimilated into a collective social actor, that is, villagers. Thus, the witch-hunt discourse is defocused and revolves around prevalent narratives of superstition and black magic.

Eliminating Gender-based Power Dynamics

- (16) A crusade against alcoholism could have led to the killing of the five women in Jharkhand, who were branded as witches by fellow villagers, police suspects (HT, Aug 9, 2015).

- (17) The woman was ostracized last year because villagers believed her absence would check the spell of black magic (ToI, Aug 14, 2015).

- (18) I will meet the CM and say that making tribal and backward societies aware of the superstitious belief is necessary to prevent a repeat of such incidents, Chhutni, who has rescued 40 women so far, said (HT, Mar 8, 2016).

- (19) It all started three months ago when some village women fell ill due to different reasons and their kin blamed me for it, the victim added (ToI, Nov 2, 2016).

Targeting women as witches provides ostensible clues for an alternative interpretation based on gender bias to reinforce male or group dominance (Example 16). Excluding a woman from her home and sources of livelihood, the community boycott indicates the pivotal role of male social actors in the witch-hunt phenomenon (Example 17). Victims are so helpless that they always ask the state actor (government) for help to seek protection from any type of mob violence. However, they (victims) also seem to be influenced by the state’s narratives and actions on witch-hunts revolving around an awareness campaign against superstitious beliefs (Example 18). Example 19 suggests that factors such as illness and the lack of state health treatment facilities provide scope and space for the growth of faith in supernatural powers in adverse situations.

State Actors and Actions on the Periphery of Discourse

- (20) The government had admitted that around 800 women were butchered allegedly for practicing black magic since the law was enacted in 2001 but in fact, the figure was more than double as per the records of FLAC (ToI, Aug 22, 2015).

- (21) Despite numerous awareness programmes launched by the government, Jharkhand Police records show a gradual increase in the number of witchcraft-related killings – 36 in 2012, 54 in 2013 and 56 in 2014 (till November) (HT, Aug 8, 2015).

- (22) ⋯the government is now planning to engage the information and public relations department (IPRD) to create awareness among the masses (ToI, Feb 6, 2016).

- (23) The government’s objective is to expedite trial in all such cases and speedy disposal to send a strong message, BB Mangal Murty, state law secretary, told HT (HT, Mar 8, 2016).

Although state actors have taken action against witch-hunts, the increasing number of incidences indicates that laws have failed to stop mob violence against tribal women. The main state actor, the government, seems more focused on addressing the witch-hunt phenomenon through legal actions against perpetrators and conducting awareness campaigns against superstition (Examples 20, 21). State actors expect the incidence of witch-hunts to be controlled with the help of the police and courts. Therefore, they neglect more important issues such as non-availability of healthcare infrastructure, food insecurity, malnutrition, anemia, education issues, cultural divisions, and the struggle for gender equality (Examples 22 and 23).

Discussion

Many studies have found that media texts favor powerful ideologies and dominant social actors (Van Dijk, 2015; Van Leeuwen, 2008). Reciprocal interactions between actors and structural systems forge social knowledge about social realities (Van Dijk, 2015). The institutionalization of such constructed realities provides a legitimate collective belief. Therefore, the current study investigated discursive particles embedded in the media texts of two major newspapers covering witch-hunt incidences in the tribal regions of India. Our results revealed that media narratives on gender violence demonstrate a discursive symmetry with the societal hierarchy and belief system, as evident in the witch-hunt phenomena.

Discursive Goals

Witch-hunt news narratives revolve around specific factors, such as superstition and the measures to eradicate it, including awareness campaigns and legal punishments. Important factors influencing these acts, such as gender-power dynamics, non-availability of healthcare services, poverty-stricken families, malnutrition and untimely deaths, personal revenge, social cognition, and mob psychology, are missing in the witch-hunt discourse. We observed that witch-hunt actions generally occur after untimely deaths in a village or other livelihood-related misfortunes, such as scanty rainfall or natural calamities. Although healthcare and food security are the domains of state actors when unmet, they act as major factors that strengthen belief in supernatural powers and their ability to redress misfortunes. Tribal people residing in the Indian state of Jharkhand are poor, malnourished, and vulnerable to disease (Social Welfare Statistics, 2018).

In tribal areas, the poor quality of health services means children are 45 percent more likely to die during the post-neonatal period (Narain, 2019). Furthermore, media coverage of essential health and medical care issues in India is extremely limited.

This lack of coverage is all the more surprising as health indicators in India are poorer than those in many other developing nations (Drèze & Sen, 2013). Indeed, low literacy, economic insecurity, and a lack of healthcare and communication services legitimize ethnic healing practices based on supernatural beliefs (Sinha, 2006). Among the adivasis (tribes), diseases or calamities are associated with a malicious spirit, which in turn is controlled by witches. It is the local witch-finders (Ojha) who determine that someone is a witch, and the villagers carry out collective punishment (Kelkar & Nathan, 2020). We observed that these factors were overwhelmingly suppressed and omitted from the media discourse on witch-hunting. Superstition is the prime cause of witch-hunt violence and eventually defends state actors’ role in providing a supportive environment for such incidents.

Culturally Sanctioned Violence against Women

The desire for personal revenge also represents a major and provocative reason for witch-branding and witch-hunting. Also, the existence of “witch” as a concept aids the intent of settling personal conflicts given that the tribal communities’ patriarchal power structure promotes this phenomenon. Studies have unveiled the processes that have led to the gradual transition in the status of tribal women because of belief in witchcraft and occult practices. Archaeo-historical evidence reveals that tribal women used to be herbalists, healers, and traditional doctors. This role is evident even today in the form of midwives participating in birth and death rituals (Stone, 1990; Wainwright, 1999). However, after the emergence of organized religions, women healers were considered a significant threat to patriarchal institutions. This gave rise to a new discourse, that if a woman knows how to heal, she must also know how to destroy. These socio-narratives promote the public execution of women who possess knowledge and influence as health healers or herbalists (Griffin, 1995; Levack, 2014). The analysis of witch-hunts from a gendered perspective indicates that male-dominated institutions become involved in violent acts to overpower women. Example 14 refers to organizational actors like a village institution (panchayat), and village head (mukhiya) as supporting the culprit by not taking action against men for committing crimes against women.

Giddens (1987) suggests that social actors are well aware of societal norms and functions employed to reproduce and reinforce the structure of society. Within these societal structures, witches are believed to always be women are portrayed with a frightening appearance, and are considered malign (Währisch-Oblau & Wrogemann, 2015). Example 17 indicates that tools aiding gender control are commonly used among tribal societies to maintain power structures. It is notable that it is a male social actor, the Ojha (witch-finder), who can declare that a woman is a source of black magical powers. Subsequently, the community takes violent action against those women. They may be beaten, burnt, strip-paraded, physically harmed, or killed. We observed that the selected newspapers fail to present a witch-hunt discourse from a gendered perspective. Media narratives defocus the issue away from the core actors and factors. The public execution of women as alleged witches sends other women a strong and violent message, thereby reinstalling patriarchal actors and their control. Examples 10 and 16 clarify that whenever there is a change in gender roles, the dominant gender takes appropriate action to safeguard its privileged position.

Mainstream Witch-hunt Discourse

Language is a construct of a specific cultural and historical process. That is why language and its use are shaped by various ideologies (Cameron, 2014). The news media under analysis in this study function as political actors that construct a witch-hunt discourse by focusing on superstition and the mainstream legal system. Since actors are positioned at various levels of the social structure, determined by factors such as class, status, gender, culture, and religion, the social location of an individual influences access to resources, power, opportunities, and even information—what one knows, does not know, or is prevented from knowing (Kondrat, 2002). The European colonizers, who shaped modern thoughts about society, presented their interpretations. Female deities and healers were portrayed as demonic forces (Kellogg, 2005) and colonizers referred to indigenous healing practices as “witchcraft” (Elmer, 2001). Based on these observations, it can be stated that “colonial imagery” functioned to characterise tribal practices, especially when performed by women, as superstitious and embodying demonic forces (Lara, 2008). Post-colonial interpretations referring to the “black skin white mask” help elucidate the cultural conflicts and imposition of the worldview of powerful cultures on minor cultures (Fanon, 2008). Further, the capitalist forms of the post-industrial revolution and its culture gave rise to a conflict between traditional and modern societies, and the struggle between powerful mainstream and minor indigenous cultures established the superiority of the mainstream. For example, Das (2017) suggested that traditional healers, who were dependent on herbs from the forest, were replaced by an institutionalized healthcare system. However, healthcare facilities are not easily accessible in remote villages, one of the factors promoting witch-hunts, as discussed earlier. Furthermore, the witch-hunt media discourse has suppressed or failed to foreground these non-superstitious reasons. Overtly, the newspapers intend to report only the incidences of witch-hunting, but their discursive constructions play a powerful covert role in forging specific realities that ultimately favor the status quo of the currently dominant actors.

Conclusion

The current study examined how social structures are reflected in witch-hunt discourses. Media texts on witch-hunting incidents demonstrate a pattern of suppression by powerful social actors. The textual genre of the media assimilates the individual culprits’ identities into a largely anonymous group identity. The lexical flow of aggressive markers has been observed from anonymous groups to female actors: (i) preparing the grounds for accusation, (ii) branding an individual, almost always a woman, as a witch, (iii) collective or mob action against the alleged witch, (iv) assigning the responsibility for violence to group actors to defend the individual identity of the culprits, and (v) establishing superstition as the main cause by suppressing alternative reasoning.

This is how the cultural sanction of violence against women functions and the media discourse, knowingly or unknowingly, follows the prevalent narratives that support conventional gendered positions and stereotyped interpretations. The media discourse legitimizes superstition as the reason for witch-hunts and simultaneously omits alternative discursive dimensions, such as gender power dynamics, health hazards, food insecurity, natural calamities, and lack of education. It appears from our results that the media prefer popular narratives of superstition by neglecting correlated realities. Their discourse also ignores the role of invisible actors and invisible factors. Scholars have already pointed out how the language of media manifests the actors and factors while strategically suppressing or enhancing the thematic content of discourse (Fairclough, 2013; Hart, 2011; Merton, 2016; Van Dijk, 2015). In its witch-hunt discourse, the media minimizes latent phenomena and hides them behind the popular mainstream narratives of tribal superstition. In this sense, the textual content of news is not merely a sentential structure; its textual functions extend beyond discursive ideologies to societal structures. Therefore, the projection of exophoric discursive narratives by the media should first be critically examined at the endophoric level.

In this regard, media discourse should be critically examined by considering the covert dimensions functioning behind any episodic and historical event. This can positively impact individuals, institutions, and society. Therefore, we consider the witch-hunt phenomenon to be influenced by various sociocultural, legal, and political factors. In this regard, the current study attempts to combine qualitative and quantitative approaches covering socio-psychological, anthropological, geographical, and economic factors to analyze the exophoric goals of the witch-hunt discourse. Although the current study is limited to this discourse in two English-language newspapers, our future studies will seek to explore the vernacular media for a better understanding of the witch-hunt discourse.

References

-

Adeney, M. (2020). 1. What is natural about witchcraft? OKH Journal: Anthropological Ethnography and Analysis Through the Eyes of Christian Faith, 4(1), 52–54.

[https://doi.org/10.18251/okh.v4i1.61]

-

Adinkrah, M. (2011). Child witch hunts in contemporary Ghana. Child Abuse & Neglect, 35(9), 741–752.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.05.011]

- Audit Bureau of Circulation. (2018). Retrieved August 16, 2020, JJ 2022 Highest Circulated (language wise).pdf (auditbureau.org, )

-

Behera, H. C. (2019). Land, property rights and management issues in tribal areas of Jharkhand: An overview. In M. Behera (Ed.), Shifting perspectives in tribal studies, (pp. 251–271). Singapore: Springer.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-8090-7_13]

-

Behringer, W. (2016).Witchcraft and the media. In M. E. Plummer (Ed.), Ideas and cultural margins in early modern Germany: Essays in honor of H. C. Erik Midelfort (pp. 243–262). London: Routledge.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315252803]

-

Berger, H. A., & Ezzy, D. (2009). Mass media and religious identity: A case study of young witches. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 48(3), 501–514.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5906.2009.01462.x]

-

Brezina, V. (2018). Statistics in corpus linguistics: A practical guide. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316410899]

-

Brooke, J., & Ojo, O. (2020). Contemporary views on dementia as witchcraft in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic literature review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(1-2), 20–30.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15066]

-

Cameron, D. (2014). Gender and language ideologies. In S. Ehrlich, M. Meyerhoff, & J. Holmes (Eds.), The handbook of language, gender, and sexuality, (pp. 279–296). New York, NY: Wiley.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118584248.ch14]

- Chakrabarty, D. (2008). The power of superstition in public life in India. Economic and Political Weekly, 43(20), 16–19. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40277682

- Chaudhuri, S. (2013). Witches, tea plantations, and lives of migrant laborers in India: Tempest in a teapot. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

-

Damodaran, V. (2002). Gender, forests and famine in 19th-century Chotanagpur, India. Indian Journal of Gender Studies, 9(2), 133–163.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/097152150200900201]

-

Das, S. (2017). Gender, power and conflict of identities: A witch hunting narrative of Rabha women. South Asian Survey, 24(1), 88–100.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0971523118783037]

-

Drèze, J., & Sen, A. (2013). An Uncertain Glory. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.23943/9781400848775]

-

Elmer, P. (2001). Towards a politics of witchcraft in early modern England. In S. Clark (Ed.), Languages of Witchcraft (pp. 101–118). London: Palgrave.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-333-98529-8_6]

-

Englund, H. (2007). Witchcraft and the limits of mass mediation in Malawi. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 13(2), 295–311.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9655.2007.00429.x]

-

Fairclough, N. (2013). Critical discourse analysis. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203809068]

- Fanon, F. (2008). Black skin, white masks. New York, NY: Grove Press.

-

Farrell, M. (2019). Witch hunts and census conflicts: Becoming a population in colonial Massachusetts. American Quarterly, 71(3), 653–674.

[https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2019.0048]

-

Fawzi, N. (2018). Beyond policy agenda-setting: Political actors’ and journalists’ perceptions of news media influence across all stages of the political process. Information, Communication & Society, 21(8), 1134–1150.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1301524]

- Giddens, A. (1987). Social theory and modern sociology. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press.

-

Griffin, W. (1995). The embodied goddess: Feminist witchcraft and female divinity. Sociology of Religion, 56(1), 35–48.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/3712037]

-

Harris, A. (2018). Witch-hunt. Studies in Gender and Sexuality, 19(4), 254–255.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/15240657.2018.1531514]

-

Hart, C. (2011). Force-interactive patterns in immigration discourse: A cognitive linguistic approach to CDA. Discourse & Society, 22(3), 269–286.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926510395440]

-

Hund, J. (2004). African witchcraft and western law: Psychological and cultural issues. Journal of Contemporary Religion, 19(1), 67–84.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/1353790032000165122]

- Indian Readership Survey (2019). Retrieved August 16, 2020, from IRS Topline Findings (mruc.net, )

- Kamat, S. (2002). Development hegemony: NGOs and the state in India. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

-

Kelkar, G., & Nathan, D. (Eds.). (2020). Witch hunts: Culture, patriarchy, and structural transformation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108490511]

- Kellogg, S. (2005). Weaving the past: A history of Latin America's indigenous women from the prehispanic period to the present. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

-

Kennedy, G. (2014). An introduction to corpus linguistics. London: Routledge.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315843674]

-

Kondrat, M. E. (2002). Actor-centered social work: Re-visioning “person-in-environment” through a critical theory lens. Social Work, 47(4), 435–448.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/47.4.435]

-

Lam, P. W. (2018). The discursive construction and realization of the Hong Kong brand: A corpus-informed study. Text & Talk, 38(2), 191–215.

[https://doi.org/10.1515/text-2017-0037]

- Lara, I. (2008). Goddess of the Americas in the decolonial imaginary: Beyond the virtuous virgen/pagan puta dichotomy. Feminist Studies, 34(1/2), 99–127. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20459183

- Levack, B. P. (2014). The decline and end of witchcraft prosecutions. In H. Parish (Ed.), Superstition and Magic in Early Modern Europe: A Reader, (pp. 336–372). London: Bloomsbury Academic Press.

-

Macdonald, H. M. (2015). Skillful revelation: Local healers, rationalists, and their ‘trickery’ in Chhattisgarh, Central India. Medical Anthropology, 34(6), 485–500.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2015.1040491]

-

Magliocco, S. (2020). Witchcraft as political resistance: Magical responses to the 2016 presidential election in the United States. Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions, 23(4), 43–68.

[https://doi.org/10.1525/nr.2020.23.4.43]

-

McBride, P. (2019). Witchcraft in the East Midlands 1517-1642. Midland History, 44(2), 222–237.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/0047729X.2019.1667109]

-

McConnell-Ginet, S. (2014). Meaning-making and ideologies of gender and sexuality. In S. Ehrlich, M. Meyerhoff, & J. Holmes (Eds.), The handbook of language, gender, and sexuality, (316–334). New York, NY: Wiley.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118584248.ch16]

-

Merton, R. (2016). Manifest and latent functions. In R. Merton (Ed.), Social Theory Re-Wired (pp. 68–84). London: Routledge.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315775357]

-

Mitra, A. (2008). The status of women among the scheduled tribes in India. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 37(3), 1202–1217.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2006.12.077]

-

Narain, J. P. (2019). Health of tribal populations in India: How long can we afford to neglect? The Indian Journal of Medical Research, 149(3), 313–316.

[https://doi.org/10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_2079_18]

- National Crime Record Bureau. (2018). Retrieved November 10, 2020, from Crime in India - All Previous Publications | National Crime Records Bureau (ncrb.gov.in)

-

Pelican, M. (2016). Customary, state and human rights approaches to containing witchcraft in Cameroon. In M. Pelican (Ed.), Permutations of Order (pp. 149–164). London: Routledge.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315600062]

- Pennebaker, J. W., Boyd, R. L., Jordan, K., & Blackburn, K. (2015). The development and psychometric properties of LIWC2015. Austin, TX: The University of Texas at Austin. Available from http://hdl.handle.net/2152/31333

-

Puri, B. (2015). The Tagore–Gandhi debate: An account of the central issues. In The Tagore-Gandhi debate on matters of truth and untruth (pp. 1–31). New Delhi: Springer.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/978-81-322-2116-6]

-

Raza, G. (2018). Scientific temper and cultural authority of science in India. In M. W. Bauer, P. Pansegrau, & R. Shukla (Eds.), The Cultural Authority of Science (pp. 32–43). London: Routledge.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315163284]

-

Reed, I. A. (2015). Deep culture in action: Resignification, synecdoche, and metanarrative in the moral panic of the Salem Witch Trials. Theory and Society, 44(1), 65–94.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-014-9241-4]

-

Rowe, L., & Cavender, G. (2017). Caldrons bubble, Satan's trouble, but witches are okay: Media constructions of Satanism and witchcraft. In L. Rowe & G. Cavender (Eds.), The Satanism Scare (pp. 263–276). London: Routledge.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315134741]

-

Roy, P. (1998). Sanctioned violence: Development and the persecution of women as witches in South Bihar. Development in Practice, 8(2), 136–147.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/09614529853765]

- Sharma, K. (2018). Mapping violence in the lives of Adivasi women. Economic & Political Weekly, 53(42), 45.

-

Sinha, S. S. (2006). Adivasis, gender and the ‘evil eye’: The construction(s) of witches in colonial Chotanagpur. Indian Historical Review, 33(1), 127–149.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/037698360603300107]

-

Smångs, M. (2016). Doing violence, making race: Southern lynching and white racial group formation. American Journal of Sociology, 121(5), 1329–1374.

[https://doi.org/10.1086/684438]

- Social Welfare Statistics. (2018). Retrieved December 02, 2022, from Handbook on Social Welfare Statistics | Department of Social Justice and Empowerment - Government of India

- Stone, M. (1990). Ancient mirrors of womanhood: A treasury of goddess and heroine lore from around the world. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

-

Sundar, N. (2001). Divining evil: The state and witchcraft in Bastar. Gender, Technology and Development, 5(3), 425–448.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/09718524.2001.11910014]

-

Van Dijk, T. A. (2015). Critical discourse analysis. In D. Tannen, H. E. Hamilton, & D. Schiffrin (Eds.), The handbook of discourse analysis (pp. 466–485). New York, NY: Wiley.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118584194.ch22]

-

Van Leeuwen, T. (2008). Discourse and practice: New tools for critical discourse analysis. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195323306.001.0001]

- Währisch-Oblau, C., & Wrogemann, H. (Eds.). (2015). Witchcraft, demons and deliverance (Vol. 32). Münster, Germany: LIT Verlag Münster. https://www.lit-verlag.de/isbn/978-3-643-90657-1

-

Wainwright, E. M. (1999). En-gendered readings of healing in the ancient world: Developing a methodological approach. Australian Feminist Studies, 14(30), 345–355.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/08164649993164]

-

Xaxa, V. (2004). Women and gender in the study of tribes in India. Indian Journal of Gender Studies, 11(3), 345–367.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/097152150401100304]

Biographical Note: Roopak Kumar is a Ph.D. Scholar in the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, National Institute of Technology, Raipur, India. He obtained dual master’s degrees –Media Studies and Anthropology. He qualified for the UGC-NET and JRF fellowship in the fields of mass communication, tribal languages and education. His research domains include socio-linguistics, critical discourse and media text analysis, conflicts and peace narratives. Contact: Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, National Institute of Technology–Raipur, G.E. Road, Raipur, Chhattisgarh 492010, India. E-mail: roopakraag@gmail.com. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9021-3402

Biographical Note: Dr Shashikanta Tarai received his Ph.D. from the Indian Institute of Technology Madras, India. After his Ph.D., he completed his postdoctoral research at the Centre of Behavioural and Cognitive Sciences, University of Allahabad, India. His research interest includes linguistics, sociolinguistics, psycholinguistics and discourse analysis. He is currently serving as Assistant Professor in the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, National Institute of Technology Raipur, India. E-mail: starai.eng@ nitrr.ac.in. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2457-2866

Biographical Note: Dr. Moksha Singh obtained her Ph.D. from Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur, India. Her area of research includes sociology, sociolinguistic, sociology of language and discourse analysis. She is currently serving as Assistant Professor in the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, National Institute of Technology–Raipur, India. E-mail: msingh.eng@nitrr.ac.in, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6165-3775