The Types of Parenting Behavior of Grandchildren During Early Childhood by Paternal and Maternal Grandmother: The Q Methodological Approach

Abstract

The purpose of this study is to validate the structure of the types of parenting behavior of grandchildren by paternal grandmothers and maternal grandmothers, and then understand them. Methodology Q, which is a research method employed to study people’s subjective points of view, was used. Forty Q statements (Q-samples) were derived from the Q population (Concourse) and arranged in order by each of the 35 participants following the normal distribution grid (from -4 to +4). The QUANL program was used to analyze the data collected. The four types of parenting behavior of grandchildren by grandmothers include the “type of parenting behavior for enhanced character,” “type of parenting behavior for enhanced emotions,” “type of parenting behavior for developed social skills,” and “type of parenting behavior for enhanced health.” The findings suggest that grandmothers who rear their young grandchildren need to be provided with educational programs appropriate for each type to achieve optimal growth and development.

Keywords:

Infant, child, grandmother, parenting, child parentingIntroduction

Need for the Study

While women begin their role as mothers at an important point in their lives following the delivery of their children, they undergo numerous experiences of psychological change including in particular, anxiety, worry, and stress given the relevant responsibilities. They are faced with countless difficulties if they concurrently pursue the development of their professional career and parenting their children (Evans et al., 2016). As of 2020, the rate of employment for married women was 55.5%, which demonstrates that women’s involvement with economic activities has continued to rise. However, 79.1% of married women who were employed experienced difficulties in pursuing their work and family life concurrently, of whom 29.2% experienced difficulties in parenting their children (Statistics Korea, 2020).

The biggest difficulties experienced by working women in child parenting are heavy childcare and housework burdens, childcare costs, and stable childcare facilities where they can send their children based on trust (Statistics Korea, 2018). To address such issues, the Korean government provides policy support such as that covering parenting behavior expenses and the expansion of day care centers. However, day care services are neither of quality that is to the users’ satisfaction nor are various methods of use provided in line with the types of parental employment and hours of work. Hence, it is inadequate to satisfy the needs of dual-income families. Furthermore, it has been reported that since Korean society is family centered, the parenting behavior of children by an individual, in particular, by a grandmother, is preferred over day care centers; the younger the children are, the higher the rate of participation of the grandmother’s parenting behavior for double-income families’ infants (59.0% for those aged less than 1 year and 50.5% for those aged 5 or younger, respectively) (Maehara & Takemura, 2007).

Infancy and childhood are critical developmental periods, and depending on the caregiver's infancy and childhood, the child's attitude and behavior can change and affect beliefs and values (Vásquez-Echeverría, Alvarez-Nuñez, Gonzalez, Loose, & Rudnitzky, 2022). Given that infancy is the period when infants acquire self-control or regulation, their social experiences are expanded, and their basic social skills are developed, the acts of parenting behavior based on the interaction between the main caregiver and the child is particularly influential on their physical growth, linguistic development, social awareness, and emotional development (Craft, Perry- Jenkins, & Newkirk, 2021). From the outset, grandparents' participation in parenting is a very strong support for the grandchildren's generation, as it supports the role of parents when needed, promotes the growth and development of children through inter-generational communication, and can share parenting responsibilities with parents (Xiao & Loke, 2022). Yet, grandmothers feel distressed and responsible about the parenting behavior of grandchildren given their tendency to play the role of an ideal grandmother in line with the institutionalized norms of their inner selves and behaviors; if their caregiving for their grandchildren is neglected, they may very easily feel guilty and experience difficulties in parenting behavior (Tang, Li, Rauktis, Farmer, & McDaniel, 2022).

According to previous studies, the difficulties caused by grandmothers’ parent-ing behavior turned out to be a physical burden that included aggravated suffering caused by concurrently carrying out house chores and parenting behavior, stress caused by forgetfulness and fatigue, and declining health, as well as psychological burdens, including the lack of time dedicated to themselves, a sense of responsibility to provide for their grandchildren, and an inner struggle with and among the members of their family (Bates & Goodsell, 2013). In contrast, the grandmother’s act of parenting behavior elicits not only pleasure and satisfaction based on her grandchildren’s growth but also psychological rewards (Condon, Luszcz, & McKee, 2020). For a double-income family, grandmothers need to play the role of the main care giver (Cox, 2009).

Currently, the extent of grandmother's participation in parenting behavior for grandchildren is extensive given the much higher level of dependence and reliability of parenting grandchildren for the dual-income family than that expected for nannies or babysitters, studies exploring how the grandmother perceives and acts concerning parenting her grandchildren are very scarce.

This study is focused on the subjectivity expressed in regard to parenting infant grandchildren. Accordingly, the purpose of this study was to verify the structure of the act of parenting by applying Methodology Q to categorize grandmothers’ parenting and explain the characteristics of each type of behavior for their infant grandchildren. These characteristics have been used as the basis for recommending more rational parenting of grandchildren.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study is to describe, explain, and categorize the characteristics of each type of parenting behaviors used by grandmothers caring for their infant grandchildren by applying Methodology Q.

Research Design

This exploratory study applied Methodology Q as an approach to verifying the parenting behavior patterns of grandparents caring for grandchildren in their infancy and childhood, and explaining the characteristics of each type.

Sampling Method

Selection of population Q.

To collect Q statements, in-depth interviews were conducted with the grandmothers of infants and children of parenting behaviors, and the results of analyzing the recorded contents and statements derived after reviewing the research literature. In-depth interviews for the formation of population Q were conducted with a total of 20 grandparents who had experience in parenting grandchildren who were infants or children during March 2020. In this process, the subjects were asked, “What are the acts of parenting carried out for the optimal growth and development of grandchildren who are infants and children?” and “What do you think ought to be the act of parenting for grandmothers?“ In-depth interviews were conducted until the responses to the question reached saturation and no new data were forthcoming. Furthermore, in-depth interviews were conducted on the views of the parenting experience and thoughts about areas of childcare, life, family, and society. The interviews took about one to two hours per interviewee, and after obtaining their consent for the interview, all details were voice recorded and transcribed in writing to prevent omissions. Data obtained from academic journals and dissertations within the last 10 years, the cumulative index of nursing and allied health literature (CINAHL), previous studies related to the parenting of foreign grandmothers provided by PubMed, professional books, Google and Naver data, etc., were combined, and a total of 350 population Qs were extracted. A total of 150 population Qs were extracted through the process of revision and re-extraction of statements through in-depth discussions by three nursing professors.

Selection of sample Q.

Sample Q was prepared by creating mutually exclusive statements while integrating and arranging statements with similar meanings. The population Q prepared for the selection of sample Q was repeatedly re-read, and the statements thought to have a common meaning or value were combined and categorized by subject. Furthermore, the ratio of affirmative and negative statements was similarly established to ensure that the attributes of each type could be clearly articulated through the sample Q classification; the statements were selected with the words appropriate for the level of the subjects, while ambiguous sentences were revised for clarity. Through this process, the four “types of grandmothers’ acts of parenting” were categorized, and the statements belonging to each category ranged from a minimum of 19 to a maximum of 112. The categorization process was modified and supplemented on the advice of two nursing professors with experience in Q-method research of selecting statements. In this process, the final sample Q consisted of 40 questions (Figure 1). After preparing sample Q, a preliminary survey was conducted with three grandparents parenting their grandchildren in infancy and childhood to check the classification time, which statements took a long time, and whether they were confusing, thereby maintaining the meaning of the contents and clarifying ambiguous sentences. To verify the reliability of the selected sample Q, two child nursing professors conducted a test-retest process at intervals of two weeks, and thereby confirmed that the sample was reliable.

Selection of sample P.

The number of samples P in Methodology Q is generally about 40 ± 20. Hence, in this study, sample P consisted of grandmothers who cared for their infants and children of normal growth and development status without chronic diseases or disabilities and who visited public health centers and pediatricians located in Seoul, Gyeonggi-do, Gyeongsangbuk-do, and Gangwon-do; these participants were selected by purposive sampling and snowball sampling.

A total of 35 grandparents of infants and children agreed to participate in this study, including those who participated in the in-depth interviews to form population Q; they were randomly selected by the researcher, although the grandmothers’ age, grandchildren’s age, number of grandchildren, and grandchildren’s gender were taken into consideration. The demographic characteristics of the participants were identified by age, gender, religion, and occupation, and the characteristics of grandchildren were identified by gender, age, birth order, and health status. The subjects were recruited from July 1, 2020, through August 31, 2020, after listening to an explanation of the purpose and contents of the study and agreeing to participate in writing.

Classification of sample Q.

Sample Q was classified according to the principle of Methodology Q, which mandatorily distributes 40 statements selected as sample Q according to the opinions of sample P. The process of Q classification is carried out in a wide and quiet space, such as a conference room during non-working hours, where the sample Q distribution can be easily seen, and where a sufficient space can be secured for the process. Prior to the start of Q classification, Sample P was asked to read and understand all of the Sample Q statements, and was asked to question any ambiguous questions. These were then clarified to ensure sufficient understanding. In the next stage, in response to the question, “What act of parenting is carried out for the optimal growth and development of grandchildren who are infants and children?” statements were freely classified as for, neutral, or against; the statements in favor of were placed on the right, those against were placed on the left, and those that were neutral placed in the middle. After the sample Q classification process was completed, interviews were conducted to confirm the reasons for the statements placed at the positive poles (+4, -4), and the contents were voice recorded.

Data analysis method.

The collected data were analyzed using the PC-QUANL Program after assigning a score of 1 or 2 points, starting with the statement with the most disagreement. To obtain the ideal results, the results were compared by calculating the various numbers of factors based on the eigenvalue of 1.0 or higher, and the most ideal classification was selected. Each type was described as a characteristic of a category by analyzing the standard score of the questions included, the difference in standard score between other types, statements that agreed more or less than the other response types, general characteristics of the subject, and the contents of the interview with the subjects. It was then named with the terms that best expressed these characteristics.

Ethical considerations.

To secure the research ethics of carrying out this study, the study was undertaken after securing approval from the *University Research Ethics Committee (IRB No. **17-200312-HR-002-01). To protect the rights of the participants, anonymity was specified, while the relevant information was provided to participants on the purpose of the study and the process, with written consent secured in advance. Consent was secured only after explaining that the subjects could withdraw from the study at any point. The subjects were also advised that the questionnaire would not be used for any purpose other than that of the study and that personal information would not be disclosed. The privacy of the participants was ensured on the first page of the questionnaire and the study carried out accordingly.

Results

Type Q's Formation

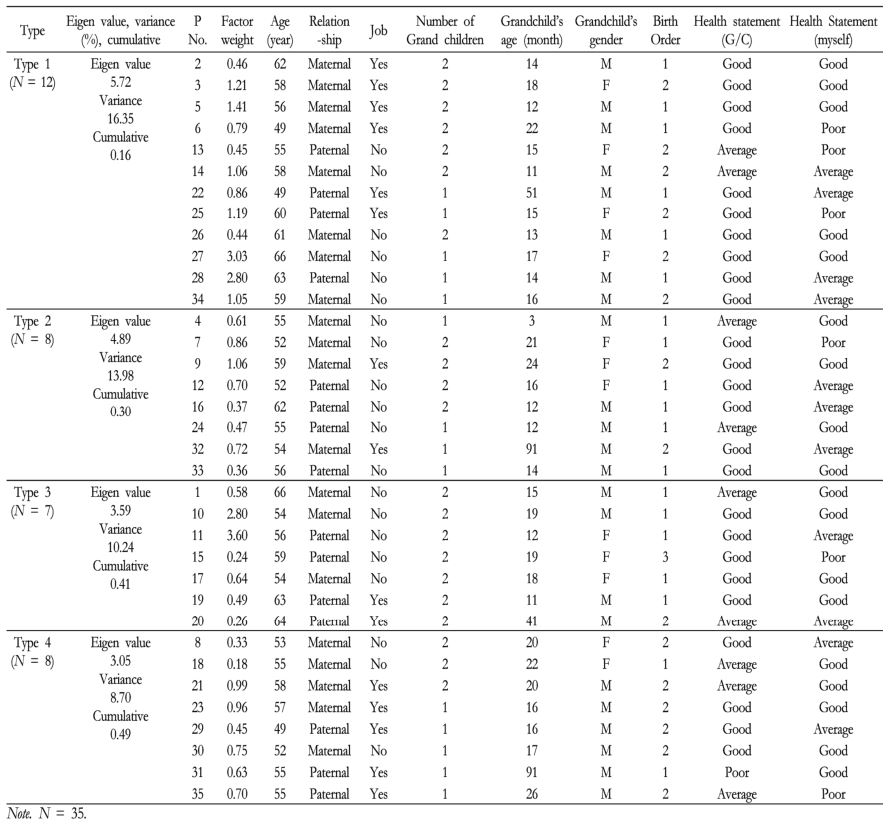

As a result of the Q factor analysis performed on the subjectivity of the participants type of parenting behavior using QUANL, four types were classified. These four types explained 49.3% of the total variance, and the explanatory power of each type turned out to be 16.4% for Type 1, 14.0% for Type 2, 10.2% for Type 3, and 8.7% for Type 4 (Table 1). Furthermore, the correlation between the types is illustrated in Table 2.

Types, Eigen values, Variance, Cumulative, Factor Weight, and Demographic Characteristics for P-sample

Type-Specific Characteristics

The subjects of the study were 12 people of Type 1, eight people of Type 2, seven people of Type 3, and eight people of Type 4. The demographic characteristics and the factor weight within each type are described in Table 1. For each type, the greater the weight, the stronger the typical characteristics of the relevant type were demonstrated by the subject.

For the analysis of the participants’ act of parenting behavior by type, the type-specific characteristics were designated according to the 40 statements described, with a focus on the questions that each subject had agreed upon positively (Z score of +1.00 or more) or negatively (Z score of -1.00 or more). Furthermore, when explaining the characteristics of each type, particular emphasis was placed on the questions with a large difference between the standard score of a specific type and the average and standard scores of other types. The Q questions and Z score (± 1.00) for each type are illustrated in Table 3.

The questions for which the subjects demonstrated the strongest agreement for Type 1 were “Educating grandchildren to be able to determine what is right and wrong” (Z = 2.12) and “Helping grandchildren form appropriate values based on a wealth of life experiences” (Z = 1.55). In contrast, the questions for which those of Type 1 demonstrated the most negative agreement were “Helping grandchildren learn manners” (Z = -2.33) and “Helping grandchildren build developed social skills” (Z = -1.75).

Subject #27, who demonstrated the largest factor weight of 3.03 among those of Type 1, was a 66-year-old maternal grandmother who was parenting her second granddaughter (16 months old). The question for which subject #27 most agreed was “Educating grandchildren to be able to determine what is right and wrong,” and she reasoned that “Growing with character in today’s world is most important.” Meanwhile, the question for which she gave a negative disagreement was “Helping grandchildren learn manners” with the reasoning that “Knowing manners today is most important, and young children lack manners.”

Making an examination based on questions such as the grandchildren’s character, proper values, determination of right and wrong, manners, and the provision of wisdom for life and experiences, Type 1 stressed the need to provide character-related education for their grandchildren with a focus on their consideration for others or values of life in their course of growth when parenting their infant grandchildren. They were classified as having the “type of parenting behavior for enhanced character” as they were determined to be the those who considered each individual’s characteristics, such as enhanced character, as important to ensure that their grandchildren become proper members of society.

The questions for which the subjects demonstrated the strongest agreement for Type 2 were “Caring for grandchildren with love and affection” (Z = 2.16) and “Helping grandchildren form emotional stability” (Z = 1.95). The questions for which those of Type 2 demonstrated the most negative agreement were “Understanding how grandchildren feel” (Z = -1.88) and “Promoting a good environment for grandchildren” (Z = -1.56).

Subject #9, who demonstrated the largest factor weight of 1.08 among those of Type 2, was parenting her second maternal granddaughter, who was 24 months old. The question with which she most agreed was “Caring for grandchildren with love and affection,” with the reasoning that, “Parenting children was very difficult when I was young.” She stated that, “My children grew on their own without ever giving me the chance to give them my love. Now, however, everything is different, and I have much love and affection for my granddaughter. This is why I can care for her with love and affection.” Meanwhile, the question for which she gave a strongly negative agreement was “Understanding how grandchildren feel” with the reasoning that “It is important for me to understand how my granddaughter feels.”

Examining the results above, it turned out that grandmothers of Type 2 provide comfort for their grandchildren and help them grow up in a good environment, unlike the character-centered parenting behavior practiced by those of Type 1. As the details show, grandmothers value their grandchildren’s emotional development. This was named the “type of parenting behavior for enhanced emotions” as they were de-termined to be the subjects who believed that mental health and emotional development influenced by the surrounding environment were important factors in the grandmother’s care of infants.

The questions for which the subjects demonstrated the strongest agreement for Type 3 was “Guiding grandchildren to become good members of the community” (Z = 1.87) and “Helping grandchildren build developed social skills” (z = 1.87). The questions for which those of Type 3 demonstrated the most negative agreement were “Educating grandchildren develop their character and care for others” (Z = -1.49) and “Helping grandchildren become healthier than other children” (z = -1.48).

Subject #11, who demonstrated the largest factor weight of 3.60 among those of Type 3, was a 56-year-old grandmother who was parenting her 12-month-old granddaughter. The question with which she most agreed was “Guiding grandchildren to become good members of the community” and she reasoned that “Becoming good members of the community is difficult as people give birth to only one child today. Helping my grandchild become a good member of the community is important in my parenting behavior of my grandchild.” Meanwhile, the question for which she gave a strongly negative agreement was “Educating grandchildren to develop their character and care for others,” and she reasoned that “Consideration for others is most important in today’s selfish society and it is crucial for developing one’s character.”

Examining these results, it can be seen that those of Type 3 place the largest importance on developed social skills, unlike those of the type who stress character and emotional development. This is apparent in terms of the positive weight placed on developed social skills rather than love and affection for negative consent, or their physical and mental development. Those of Type 3 were described as those with the “type of parenting behavior for developed social skills” as they were determined to be the subjects who considered that social skills were crucial for parenting their grandchildren to become proper members of community along with infant-related issues based on their development via interpersonal relationships, such as by pursuing their roles as members of their community in the parenting behavior of their grandchildren.

The questions for which the subjects demonstrated the strongest agreement for Type 4 were “Preparing snacks and guiding eating habits for grandchildren” (Z = 2.14) and “Helping grandchildren become healthier than other children” (z = 1.73). Conversely, the questions for which those of Type 4 demonstrated the most negative agreement were “Helping out with the average growth and development for the grandchildren’s developmental phases” (Z = -2.33) and “Reading fairy tales and drawing pictures for the grandchildren’s developmental phases” (Z = -1.76).

Subject #21, who demonstrated the largest factor weight of 0.99 among those of Type 4, was a 58-year-old maternal grandmother who had occupation and was parenting her 20-month-old grandson, who is the second oldest. The question with which she most agreed was “Preparing snacks and guiding eating habits for grandchildren” and she reasoned that “My grandson’s health must be studied carefully, and preparing snacks and good food for my grandson’s healthy growth is essential for shaping solid eating habits.” Meanwhile, the question for which she gave a strongly negative agreement was “Helping out with the average growth and development for the grandchildren’s developmental phases” where she reasoned that, “Attention must be paid to my grandson’s proper growth. Among my responsibilities is to make sure that he gets a medical checkup and is well.”

Analyzing the results above, it may be considered that the previous types emphasized character and emotional and social skills development, whereas the grandmothers of Type 4 valued the development of physical health. Those of Type 4 were named the “type of parenting behavior for enhanced health” as they were determined to be the subjects who considered nutrition and physical health to be the most important factors of parenting behavior considered by the grandmothers.

Inter-Type Items of Agreement

Given the results above, the parenting behavior of the infants' grandmothers is classified into four types, each of which demonstrates very distinct characteristics. However, the grandmothers who corresponded to the four types commonly made their statements agreeing or disagreeing over parenting behavior, based on the fact that “Parenting behavior for grandchildren is harder than parenting behavior for children” (Z = 0.94). That is, it was apparent that to the grandmothers that parenting their grandchildren is considerable work, as they require themselves to be far more cautious than when they raised their own children (Table 4).

Discussion

In evaluating human behaviors, subjectivity provides for a model that helps one determine how to internalize the state of emotions related to an individual's psychological events (Bigner & Gerhardt, 2013). In this study, an attempt was made to identify the types of parenting behavior adopted by grandmothers caring for their infant grandchildren by applying Methodology Q, which begins with the subjectivity of the study subjects, rather than the perspective of the researcher. As a result, the types of grandmothers’ parenting behavior was classified into “type of parenting behavior for enhanced character,” “type of parenting behavior for enhanced emotions,” “type of parenting behavior for developed social skills,” and the “type of parenting behavior for enhanced health.”

Examining previous studies on the subjectivity of the act of parenting behavior in infancy, in a study conducted by Park et al. (2012), it was confirmed that the parents’ acts of parenting behavior were analyzed as the love-respect type, interest-observance type, consideration for others-setting example type, and warmthencouragement type (Park, Kang, & Kim, 2013). A later study that investigated the father’s act of parenting behavior during infancy verified types, as the character and development- centric type, developed social skills-centric type, physical health development-centric type, and values formation and development centric type (Park, Choi, Ko, Park, & Park, 2019). As such, while there were some differences in terms of the attitude toward parenting behavior depending on the study subjects, similar aspects were also discovered. Furthermore, it is apparent that the physical, mental, and social aspects were stressed in both integral and comprehensive manners in grandmothers’ parenting behavior of their children and grandchildren.

The grandmothers in this study were primarily middle-aged and undergoing the early phase of their old age. It was evident that it is common for them to become grandparents in their 40s and 50s if they married early or if their children married early and in their mid-60s if they married late. Middle-aged people in their 40s and 50s were adapting themselves to the physical and social changes caused by aging, and at the same time, had a job and were assisting their children by parenting their grandchildren. The physical, psychological, and social issues they have experienced from middle age through the early phase of their old age, the need for parenting their grandchildren, and the quality of their parenting behavior combined varied depending on the developmental tasks and characteristics experienced by the grandmothers themselves. Hence, it would be necessary to understand and verify the changes and perception of grandmothers’ parenting behavior of grandchildren by undertaking more specific and continuing studies.

As a result of this study, Type 1, which demonstrated the largest explanatory power, was the “type of parenting behavior for enhanced character.” These grandmothers most wanted their grandchildren to have a good character as members of society. Hence, they considered that character is important when parenting their grandchildren and determined that that involved helping their grandchildren form proper values based on a wealth of life experiences. Similar to this study was the study of Park et al. (2019), which verified grandmothers to be “Forming good values in their grandchildren” and “Helping their grandchildren form a good character.” Furthermore, a study by Park and Rhee (2001) demonstrated that determining appropriate limits and rules for the behaviors of grandchildren during their infancy plays an important role in their character development a finding that is also similar to the results of this study. In addition to the parenting behavior of grandchildren, it was verified that character education, as parents rear their children, is very helpful for their children’s interpersonal relationships in the future because forming good character in their children is based on their consideration for others, communication, responsibility, and self-direction, etc. (Chin, Lee, & Seo, 2014). Accordingly, it is necessary to review and understand more specifically which criteria and perceptions grandmothers have toward character education and how they rear their grandchildren. Furthermore, because the parenting behavior of grandchildren per life cycle may demonstrate differences depending on each life cycle, such as the neonatal period, infancy, early childhood, pre-school age, and school age, a repeated verification of the grandmother's act of parenting behavior across various life cycles will be required.

Those of Type 2 were of the “type of parenting behavior for enhanced emotions,” and most of the grandmothers expressed the belief that their role as a care giver was to help their grandchildren develop emotional stability by giving them their love and affection. As a result of looking at previous studies (Park & Kang, 2015; Lee, 2012; Rha, 2005), it was verified that affection and love are the feelings of caring, support, and acceptance of interest, and are also the parents’ act of understanding their children and expressing their affections verbally and non-verbally, similar to the results in this study. Furthermore, a variety of previous studies confirm the fact that the tendency for the act of affectionate parenting behavior in the grandmothers’ parenting behavior of their children and grandchildren is a key type of act of parenting behavior in Korea today; it was also evident that grandmothers could positively influence their grandchildren with their affections and love formed based on their experiences and the surrounding environment over the long term (Rha, 2005; Lee, 2012; Bigner & Gerhardt, 2013; Park et al., 2013; Park et al., 2019).

Among the results of this study, grandmothers also agreed to create an emotionally comfortable and happy environment by focusing on their grandchildren’s parenting behavior. On the other hand, the questions for which they demonstrated the most negative agreement was confirmed to be “Understanding the grandchildren’s feelings,” and hence, it may be said that the grandmothers carry out their parenting behavior of grandchildren, which values the emotional well-being with their affections, with a focus on their grandchildren, in parenting children. Hence, by providing educational materials on the characteristics of each developmental phase of infancy and the acts of parenting behavior for the grandmother parenting their grandchildren, it will be necessary to provide accurate information on enhancing grandchildren’s emotions to ensure that they form a positive attachment while elevating their understanding of the parenting behavior of grandchildren.

It is evident that those of Type 3 were of the “Type of parenting behavior for developed social skills,” and they perceived forming interpersonal relationship and guiding social skills to be the most important roles in parenting their grandchildren. Such results are similar to the categories of interpersonal development and proper discipline demonstrated in a previous study that analyzed the details of the act of parenting behavior for the mothers of children in infancy (Park, 2014), and are also similar to the classification of the roles of parents explained in a previous study on the concept of parental roles of college and university students for enhanced discipline and social skills. Hence, it is apparent that developed social skills and the role of discipline are commonly perceived as important (Lee, Kang, & Park, 2012). That is, it is an important aspect where their children can grow up properly guided by their parents and grandmothers, form interpersonal relationships, and become good members of society with the skills acquired. Accordingly, it will be necessary for parents and grandmothers to provide parents and grandmothers with the guidance and disciplinary methods for the parenting behavior of their children and grandchildren to ensure that their children and grandchildren grow into good members of their society in the future, while informing them of the relevant specifics for the subjects to learn with accuracy. Furthermore, accurate knowledge for educating grandmothers at home on how to care to help prevent their grandchildren’s inappropriate interpersonal relationships is required.

It is also evident that those of Type 4 were of the “type of parenting behavior for enhanced health,” and perceived that grandmothers ought to play the role of securing health as a top priority for their grandchildren by providing meals and snacks of good nutrition for their grandchildren. Similar results were also demonstrated in previous studies (Park et al., 2013; Park & Kang, 2015; Park et al., 2019). In fact, the consumption of fruits and vegetables in Korea has recently declined, while the issues of excessive sodium and sugar intake by and among children have continued to raise the issue of chronic diseases (Heo, Shim, & Yoon, 2017). Accordingly, to help maintain and promote the health of grandchildren, it is necessary to develop a nursing diagnosis for the development and operation of a health care-related educational program for grandmothers’ parenting behavior and for the development of parents’ and grandparents’ educational intervention.

Given the declining birth rate and the increased number of working women, grandparents’ participation in the parenting behavior of their grandchildren has risen (Choe, 2017). Such changes over time have reduced the performance of the parental role following the decreased number of children, yet have caused burdens on parents, further causing difficulties in the parenting behavior of grandchildren (Baeck, 2010). It is meaningful in that this study has analyzed the perception of various grandmothers having their grandchildren in infancy in line with such changes over time. Furthermore, it is even more meaningful that the grandmothers of four cities and provinces were sampled rather than limiting the sample to a single region. However, while interest has recently grown in the roles of parents and grandparents of grandchildren, there are limitations to the analysis performed. In future studies, it is necessary to analyze the perception of the acts of parenting behavior among grandmothers with their grandchildren in the neonatal period, infancy, early childhood, pre-school age, and school age. Furthermore, studies that repeatedly expand and analyze the results of this study, which has experienced limitations in performing a comparative analysis given the lack of previous studies, will need to be continued.

Conclusion and Recommendations

In this study, an attempt was made to categorize the grandmothers’ acts of parenting behavior and explain the characteristics for each type of behavior to verify the structure of the act of parenting behavior, while preparing the basic data for developing the fundamental strategies for building the grandmother's parenting behavior. As a result of this study, the four types of parenting behavior acts were verified with the grandmothers, namely, “type of parenting behavior for enhanced character,” “type of parenting behavior for enhanced emotions,” “type of parenting behavior for developed social skills,” and “type of parenting behavior for enhanced health.” Based on these types, it was confirmed that grandmothers, who are parenting their grandchildren, perceive that parenting their grandchildren to develop a good character and disposition is an important role for the grandmothers to play, while also perceiving that forming interpersonal relationships, guiding social skills, and securing health were top priorities and the provision of meals and snacks for good nutrition was essential.

In view of these results, it was apparent that to enhance the parenting capacity of grandparents, it was necessary to apply child parenting training, education, and intervention programs appropriate for the characteristics of each type of parenting.

Accordingly, in parenting their grandchildren, grandmothers ought to be required to maintain the optimal health conditions for their grandchildren based on being provided with accurate knowledge, along with the education to ensure the safety of their grandchildren’s physical, mental, social, and spiritual health. Furthermore, it will be necessary to develop programs that help grandparents actively communicate with and form supportive relationships with their children, thereby ensuring that they gain positive experiences in parenting their grandchildren.

References

-

Baeck, U. K. (2010). Parental involvement practices in formalized home-school cooperation. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 54(6), 549–563.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2010.522845]

-

Bates, J. S., & Goodsell, T. L. (2013). Male kin relationships: Grandfathers, grandsons, and generativity. Marriage & Family Review, 49(1), 26–50.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2012.728555]

- Bigner, J. J., & Gerhardt, C. J. (2013). Parent-child relations: An introduction to parenting (9th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson. pp. 1-100.

-

Chin, M. J., Lee, H. A., & Seo, H. S. (2014). Parents’ perceptions on character and character education in family. Journal of Korean Home Management Association, 32(3), 85–97.(In Korean)

[https://doi.org/10.7466/JKHMA.2014.32.3.8]

- Choe, H. J. (2017). Comparison of grandmothers’ subjective health status, depression, quality of life and conflict with their children depending on whether raising grandchildren or not. Korean Parent-Child Health Journal, 20(2), 80–87. (In Korean)

-

Condon, J., Luszcz, M., & McKee, I. (2020). First-time grandparents' role satisfaction and its determinants. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 91(3), 340–355.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0091415019882005]

-

Cox, C. (2009). Custodial grandparents: Policies affecting care. Journal of Intergenerational Relationship, 7(2-3), 177–190.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770902851221]

-

Craft, A. L., Perry-Jenkins, M., & Newkirk, K. (2021). The implications of early mar-ital conflict for children's development. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 30, 292–310.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01871-6]

-

Evans, K. L., Millsteed, J., Richmond, J. E., Falkmer, M., Falkmer, T., & Girdler, S. J. (2016). Working sandwich generation women utilize strategies within and between roles to achieve role balance. PloS one, 11(6), e0157469.

[https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157469]

-

Heo, E. J., Shim, J. E., & Yoon, E. Y. (2017). Systematic review on the study of the childhood and adolescent obesity in Korea: dietary risk factors. Korean Journal of Community Nutrition, 22(3), 191–206. (In Korean)

[https://doi.org/10.5720/kjcn.2017.22.3.191]

- Lee, E. J., Kang, Y. S., & Park, J. H (2012). A study on pre parents’ perception of parental role and view of children. Journal of the Korea Academia-Industrial cooperation Society, 13(4), 1566–1573 (In Korean)

- Lee, K. H. (2012). The relationship between family strengths and life satisfaction perceived by adolescents. (Master’s thesis, Chonnam National University, Gwangju). Available from RISS (Research Information Sharing Service). (In Korean)

-

Maehara, T., & Takemura, A. (2007). The norms of filial piety and grandmother roles as perceived by grandmothers and their grandchildren in Japan and South Korea. International Journal of Behavioral, 31(6), 585–593.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025407080588]

- Park, G. J., Kim, Y. J., Seo, M. W., Yoon, M. J., Lee, J. S., & Cho, K. O. (2012). Parent education (for parents of infants and toddlers). Paju: Yangseowon. pp. 46-72. (In Korean)

- Park, J. H., & Rhee, U. H. (2001). Children’s peer competence: relationships to maternal parenting goals, parenting behaviors, and management strategies. Korean Journal of Child Studies, 22(4), 1–15. (In Korean)

-

Park, S. J., Kang, K. A., & Kim, S. J. (2013). Types of child parenting behavior of parents during early childhood: Q-methodological approach. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing, 43(4), 486–496.

[https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2013.43.4.486]

-

Park, S. J. (2014). Content analysis of child parenting behavior s of mothers in infant and child preschool. Child Health Nursing Research, 20(1), 39–48.(In Korean)

[https://doi.org/10.4094/chnr.2014.20.1.39]

-

Park, S. J., & Kang, K. A. (2015). Development of a measurement instrument for parenting behavior of primary caregivers in early childhood. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing, 45(5), 650–660. (In Korean)

[https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2015.45.5.650]

-

Park, S. J., Choi, E. Y., Ko, G. Y., Park, B. S., & Park, B. J. (2019). Types of parenting of fathers during early childhood: A Q methodological approach. Child Health Nursing Research, 25(3), 344–354.

[https://doi.org/10.4094/chnr.2019.25.3.344]

- Rha, J. H. (2005). A suggestion for new parental roles according to children’s developmental stages: The changing parental roles and practices. Korean Journal of Human Ecology, 14(3), 411–421. (In Korean)

- Statistics Korea & Ministry of gender equality and family (2018, July). 2018 Statistics show the life of a woman. (Report No.: N/A). Retrieved October 21, 2021 from http://www.mogef.go.kr/nw/rpd/nw_rpd_s001d.do?mid=news405&bbtSn=705754, (In Korean)

- Statistics Korea (2020, December). 2020 Local area labor force survey. (Report No.: N/A). Retrieved October 21, 2021 from https://kostat.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10301030300&bid=211&act=view&list_no=386454, In Korean)

-

Tang, F., Li, K., Rauktis, M. E., Farmer, E. M., & McDaniel, S. (2022). Stress, coping, and quality of life among custodial grandparents. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 66(3), 354–367. doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2022.2103764

[https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2022.2103764]

-

Vásquez-Echeverría, A., Alvarez-Nuñez, L., Gonzalez, M., Loose, T., & Rudnitzky, F. (2022). Role of parenting practices, mother's personality and depressive symptoms in early child development. Infant Behavior & Development, 67, 101701.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2022.101701]

-

Xiao, X., & Loke, A. Y. (2022). Intergenerational co-parenting in the postpartum period: A concept analysis. Midwifery, 107, 103275.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2022.103275]

Biographical Note: Sunjung Park graduated from Sahmyook University with a Ph.D. in the Nursing Care of Children. She is currently an assistant professor in the Nursing Department of Sahmyook Health University. Email: bun8973@naver.com

Biographical Note: Eunju Choi graduated from Chosun University with a Ph.D. in nursing care of children. She is now an associate professor in the nursing department of Cheongam College. Email: cej1998@nate.com

Biographical Note: Byung-jun Park (Corresponding Author) graduated from Korea University with a Ph.D. in Nursing Science (his major was adult health nursing). He is currently an assistant professor in the Nursing Department of Daegu Health College. Email: byungjuny00@gmail.com