A Miserable Maniac, a Salacious Saracen, or a Distressed Demirep:Fighting the Erasure of an Inspiring Muslim Woman

Abstract

This article adds to the existing literature on the distorted representation of Muslim women in a fictional world. It is distinctive in its approach, in that it explores the clichéd representation of Muslim women by Anglophone writers who claim to have better access to reality because of their ethnic background. This incomplete picture is deficient in many respects, but the focus of this paper is on two main categories: first, the medievalists’ resonance of charming white Saracen and repulsive black Saracen women in Pakistani Anglophone fiction, and second, the radical exclusion of an inspiring religious Muslim woman from the fictional world. We merged the theory of social actor (SA) representation by Van Leeuwen (2008) with corpus methodology to analyze Aslam’s Maps for Lost Lovers (2004) and The Blind Man’s Garden (2013). The research concludes that the basic plot of the selected novels has only three types of Muslim women: a miserable woman resonating with Saracen, a salacious Saracen full of hatred for her community, and a distressed demirep in need of rescue. The research concludes that the latter two categories are an amalgamation of the medieval fantasy woman known as the white Saracen. This research calls for attention to this specific type of oppressive writing practice targeting Muslim women by erasing the category of inspiring Muslim women from all kinds of discourses.

Keywords:

Anglophone literature, corpus methodology, social actor, clichéd representation, radical exclusionIntroduction

The Reverberation of Islamophobia in Recent Postcolonial Scholarship

Ethnocentric anchoring recurring in European academia is discernible in the fiction of postcolonial writers, as implied by Said’s 1985 description of Orientalism. The concentration of postcolonial texts on connecting with the colonial or neo-colonial center sustains colonial ideas. This is one theory behind why “Western consumers of ‘non-Western’ items” exist (Santesso, 2013, p. 75). According to Mukherjee (1990), postcolonial textual interchange is still founded on the deeply ingrained binaries of the East and West, even after many years of decolonization. Political theorists such as Boehmer (1998) contend that when postcolonialism fails to challenge global capitalism, overt neo-Orientalism manifests itself in every discipline that bears the label.

Consequently, one of the effects of coexisting with, adapting to, and being supported by global capitalism is not demonstrating appropriate opposition. In this vicious loop where “the discursive and textual traffic of postcolonial literature is controlled from the neo-colonial centres of the capitalist globe,” he looks for a way out (Boehmer, 1998, p. 3). Challenging the underlying material conditions and inequity of cultural hierarchies can be the first step toward releasing mediated postcolonial consciousness. However, he was worried that more was required. As academics, we are responsible for learning more about the economic and political contexts that influence the creation and continuation of postcolonial scholarship. Understanding the forms of oppression and exploitation of postcolonial writers is challenging, as postcolonial studies promise to dismantle and challenge colonial authority. The importance of finding answers to the issues highlighted by postmodern postcolonial theory is noteworthy. Investigating the rationale for employing postcolonial theory, comprehending the connection between nationalist and anti-colonial literature, and examining how self-referentiality and self-reflexivity function in postcolonial literature are a few of these (Boehmer, 1998). Poststructuralist theories and postmodernist concepts have provided literary text analysis from this angle using handy analytical tools. They aid researchers in challenging the veracity of experiences depicted as postcolonial in postcolonial literature. They cast doubt on the veracity of how reality is depicted in postcolonial literature by viewing it through the cynical prism of anti-foundational thought. These theoretical tools break down the essential ideas of Western thought that postcolonial writers have repeatedly and occasionally reaffirmed. The postmodernist school of thought examines the colonial self as a monolithic character on the one hand, and the uncertain autonomy of postcolonial hybridity or its status as a by-product of unplanned European colonization on the other. Boehmer (1998) cautioned against neo-Orientalism and metamorphosis of postcolonial texts with a new name, Anglophone literature.

Radical Exclusion of a Social Actor

As highlighted by Van Leeuwen (2008), discourse producers often strategically exclude specific social actors (SAs) to advance their interests. This linguistic or literary exclusion serves various political, social, or psychological purposes and is typically employed to conceal responsibility for unfavorable actions. Namaste (2007) pointed out that purposeful erasure can be considered a form of violence, especially when it involves not reporting women’s achievements and crimes against women, leading to the collective indifference and invisibility of certain segments of society. The term “erasure” has moved beyond academic discourse and is associated with practices that dismiss inconvenient facts, groups, and their histories, problems, pain, and achievements. This concept raises questions about whose life stories are told, whose suffering is acknowledged, and whose deaths are mourned. Sims (2017) calls this phenomenon the “Matilda effect” when it pertains to the suppression of women’s achievements in science and technology. It is similar to the notion of the dangers of the single story, which reinforces existing orders and includes gregarious whitewashing of minority groups like transgender women of color.

This study argues that a similar title should be used when inspiring religious Muslim women are targeted for erasure. The complete absence of inspiring religious Muslim women in the literature of the Muslim world represents a symbolic erasure (Anderson & Anderson, 2021). Some exclusions may be naive, assuming that the audience is already aware of the details, but this is often not the case in Anglophone literature. Exclusion is also practiced in news reporting, where the police, for instance, may be excluded when force is used to control riots (Van Leeuwen, 2008). Radical exclusion leaves no trace, necessitating the comparison of multiple representations of similar events. Situating the research questions in a broader context provides nuanced insights. Omitting the SA prevents readers from verifying or contesting the representation and allows writers to evade responsibility (Van Leeuwen, 2008).

In a fictional world crafted by writers, readers often find it challenging to reintroduce excluded SAs once they have been omitted. Readers deeply engrossed in a story may not notice the absence of these excluded SAs and the fictional realities presented in the narrative are rarely questioned or examined. Recent research, such as that of Khan et al. (2021), has explored the exclusion of Muslim characters from mainstream media. However, this study focuses on a specific type of exclusion: the absence of female characters with inspiring personalities. The argument put forth in this paper is that none of the female Muslim characters depicted in “Maps for Lost Lovers” (2004) and “The Blind Man’s Garden” (2013) by Aslam can be considered esteemed or inspirational figures in any Muslim society worldwide. According to the authors, none of these characters is crafted in a way that would make readers want to emulate them. Female Muslim readers did not identify with any of these characteristics. In the fictional world created by Aslam (2004, 2013), Muslim women are portrayed as social maniacs, miserable fanatics, and salacious termagants. The authors assert that they could not find a law-abiding, cultured Muslim woman in Aslam’s literary work.

Literature Review

Islamaphobic Strands in Recent Anglophone Literature

Meer (2014) outlines the relationship between Islamic phobia and current postcolonial studies. He shows how modern postcolonial studies exhibit continuity and contends that they replicate previous colonial dynamics (p. 504). He claimed that religion is intertwined with race, resulting in the racialization of Muslims. This, in turn, highlights that opposition to Islam cannot be separated from discrimination against Muslims. In cases where Islam plays a central role in Muslim identity, disparaging Islam negatively affects respect and self-esteem. Islam is fundamental to the identities of Muslims from various civilizations worldwide as he elucidates this idea (Meer, 2014). This situation’s intricacy is comparable to earlier colonial practices, when the British could dominate thanks to assistance from the Crown or home country and by constructing numerous political and constitutional structures in the colonized areas. These political and cultural linkages created under colonialism continued to exist even after independence and, surprisingly, are the foundation of a better explanation of the neo-Orientalist components reflected in postcolonial studies (Meer, 2018).

Is Anglophone Literature an Insider’s View of the Muslim World?

After 9/11, an emerging genre mushrooming in the diaspora has been observed called “Muslim writing” (Moghissi, 2005; Chambers, 2011). Although the authenticity of these writers’ perspectives has often been challenged, the literary canon continues to serve as a powerful tool of Muslim representation. Initially, this genre was hailed as a creative tool for writing back and dispelling fabricated Muslim identities. They were acclaimed to have charted diverse aspects of Muslim identities and deconstructed false identities. However, soon exotic cultural efflorescence withered and gave way to the critics’ questions about thematic ghettoization for the sake of commercial success (Král, 2009, 2014). Some sarcastic terms, such as halal novelists and multi-culti halal writings also appeared to refer to the ethnic background of Anglophone writers (Chambers, 2010; Santesso, 2013; Squires, 2012, 2013). In this literary scenario, the representation of Muslim women is complicated and convoluted, demanding careful disentanglement. Some of these nuanced readings are discussed below, before explaining the critical approach of the current article.

Lau and Mendes (2012) discuss three key aspects of feminist Orientalism. First, it highlights how feminist Orientalism creates a binary contrast between the Western and Eastern worlds, portraying the West as progressive and ideal for women while characterizing the Muslim Orient as regressive and uncivilized for women. Second, it emphasizes that feminist Orientalism tends to view Oriental women as passive victims, rather than recognizing their agency in effecting social change, leading to the belief that they need Western saviors. Third, it assumes uniformity across all Eastern societies and that all Muslim women have identical experiences. Bahramitash (2005) argues that during the colonial era, colonizers believed that they were introducing civilization to the Orient. Today, similar methods, including warfare and occupation, are used to promote democracy in the same region, along with a war on terror, to safeguard civilization from perceived threats. To garner public support for these campaigns, a strategy from the colonial era that focused on the treatment of women in the Muslim world was revived. Bahramitash suggests that self-proclaimed feminists and Anglophone writers played a significant role in advocating this campaign, using their supposed firsthand experiences with women under Islam to portray the religion as primitive and misogynistic.

Cahill (2019) begins her book by discussing how the appearance of a Muslim woman can reinforce two contradictory stereotypes: one portrays Muslim men as oppressors and the other depicts Muslim women as passive and oppressed. Cooke (2007, 2008) introduced the term “Muslimwoman” to describe the distorted representation of a veiled Muslim woman portrayed as having a passive existence in a private harem, silenced, and devoid of agency. This neo-Orientalist stereotype serves a dual purpose and continues to be effective in today’s public discourse. It is still a matter of debate whether this stereotype arose from cultural constraints, cultural biases, or the complex historical intersection of Anglican religiopolitical authority over the past two centuries. Nonetheless, what is clear is that this portrayal of the Muslim woman as a negative ideal has persisted for centuries, denying the existence of inspiring religious Muslim women who defy these stereotypes.

Concept of Saracen: Historical Perceptions and Modern Re-evaluation

The term “Saracen women” historically referred to women from the Saracen culture, a broad and often derogatory term used in medieval Europe to describe various non-Christian, particularly Muslim, societies in the Middle East and North Africa. This term, borrowed from Latin, has been used in Old English since the ninth century, with some referring to its generic meaning as “pagan” (Bly, 2002; Speed, 1990). The concept of Saracen women was shaped by medieval European perceptions of the Islamic world during the Crusades and subsequent interactions. Europeans held stereotypical views on the roles and status of women in Islamic societies, often portraying Saracen women as exotic and mysterious figures in literature and chivalric romances (Belloc, 1913). European encounters with Saracen women during the Crusades and on trade routes sometimes led to misconceptions and misunderstandings about their cultures and practices. While modern scholarship has challenged many of these stereotypes and fallacies, emphasizing the diversity and complexity of women’s lives in the Islamic world, there is still work to be done, especially in the realm of fiction (Moghissi, 2005; Maalouf, 2012). It is important to note that the term “Saracen” carries negative historical connotations.

Tales about Muslims were a significant topic of preoccupation during the Middle Ages, as Bly (2002) noted. Recently, this practice has resurged in the literature produced and circulated by third-generation Anglophone writers. This research focuses on the portrayals of female Muslim characters, both in general Anglophone literature and specifically in Aslam’s works, as a manifestation of neo-Orientalist themes. The study identifies a reflection of medieval concepts associated with Muslim women in the female characters created by Aslam (2004, 2013), using terms like “black warrior Saracen woman” and “white Saracen woman.”

Methodology

As this is corpus-based research, we used two acronyms repeatedly to avoid repetition. The acronyms used in the article are as follows: SCBMG Study Corpus The Blind Man’s Garden (Aslam, 2013) and SCMLL Study Corpus Maps for Lost Lovers (Aslam, 2004). The analysis in this article is divided into four sections.

⦁ Section one discusses the representation of Muslim women’s representation as social monsters. It includes Kaukab from SCMLL, the miserable maniac, as an incarnation of the black warrior Saracen woman, and compares her with her counterpart Tara from SCBMG.

⦁ Section two discusses two female characters, Mahjabin (SCMLL) and Sofia (SCBMG), as distress demireps. They represent the Western “prototype” of the oppressed Muslim woman fabricated throughout history.

⦁ Section three focuses on the characteristics of Naheed from SCBMG, and Chanda and Suraya from SCMLL. All three are discussed as amalgams of distressed demirep and salacious Saracens, to varying degrees.

⦁ The fourth section discusses the radical exclusion of inspirational religious Muslim women from Aslam’s fictional world.

The following research question guided this research. How is a Muslim woman portrayed in the fictional world created by Aslam (2004, 2013)? This broad question needed to be narrowed down to more targeted questions.

⦁ Which type of Muslim woman is portrayed as included or excluded SAs?

⦁ What type of identification and evaluation do Muslim female characters receive directly from the author or through other SAs’ appraisals?

Analysis and Discussion

Kaukab and Tara: A Collectivized Embodiment of Muslim Women as Social ‘Monsters’

In literary discourse, characters often symbolize real-world groups. Kaukab in the SCMLL and Tara in the SCBMG are Aslam’s representations of religious Muslim women, reflecting his perceptions, rather than reality. This calls for a thorough deconstruction of these characteristics.

Kaukab: The Miserable Maniac in SCMLL

Kaukab, identified as Shamas’s wife and the mother of his three children, resents being in the diaspora and blames her husband. We find textual proof (Table 1) that Aslam sees her as an embodiment of religious Muslim women. In Table 1, our comments are on the left and SA’s name is in square brackets on the right. These examples show that Kaukab sees herself as distinct from the white population and identifies with the Muslim Ummah.

Ujala and Mahjabin’s critical comments on the novel reveal their broader critiques of the Muslim community when speaking to their mothers. Table 1 shows how they often use generalizations instead of directly addressing Kaukab. Shamas, Mahjabin, and Jugnu also mock Muslim values and attribute their challenges to Islamic culture. In a polarized situation, Kaukab aligns with Muslims, while her family identifies more with Western and non-Muslim communities. Kaukab’s cockeyed personality traits offer insights into Aslam’s views on Muslim women.

Kaukab as a Volatile, Tear-jerking Muslim Woman

Her word sketch showed her appearance in the subject position, with a high T-score of 72.45, suggesting her dominance. Notably, the object position had a much lower T-score of 13.96, indicating that its portrayal was dominant. Many collocations in Table 2 have a negative tone.

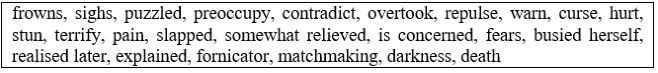

The elevated T-score in Table 2 indicates nonrandom word usage with her name. We initially compiled a comprehensive list of collocations spanning seven words on either side of the node word (NW), totaling 1500 words. To make it more manageable, we trimmed the list to an MI score of six, retaining only the words used to describe Kaukab in Table 3.

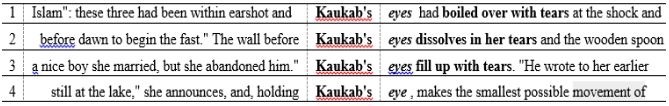

Table 3’s emotive words depict Kaukab as a highly emotional and volatile individual with strained family relationships. The recurring phrase “Kaukab’s eyes appear” in Table 4 objectifies her through possessive somatization, a technique repeatedly employed by the writer to emphasize her sense of detachment.

Table 4 highlights Kaukab’s actions, stripped of agency and portraying events unfolding beyond her control. This technique, known as the eventuation of social actions (Van Leeuwen, 2008, p. 66), shapes Kaukab as emotionally charged and lacking control over her actions, thus emphasizing their involuntary nature.

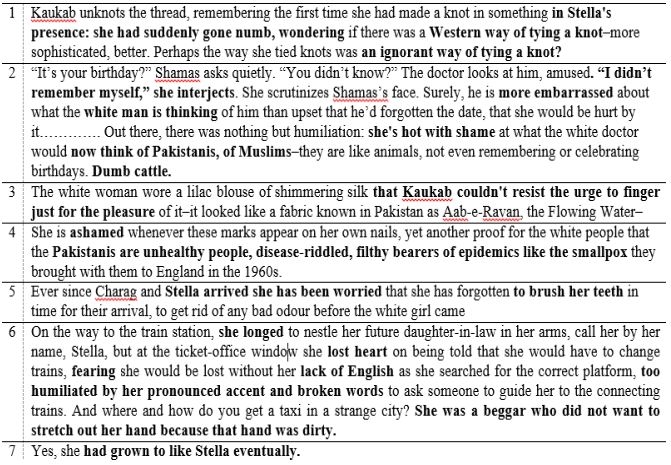

The concordance lines in Table 5 reveal Kaukab’s struggle to manage her emotions, portraying her as a lonely mother who simultaneously pushed her children away because of infuriating habits while yearning for their presence. Mental and perceptive cognitive processes like “hear,” “see,” “remember,” “know,” “hope,” “look,” and “puzzle” are used to shape her character. The lines in Table 5 demonstrate her inability to understand her family’s needs.

Authorial comments and assessments from other sources help identify her characterization as a social outcast consumed by her thoughts, causing misery for others. Metaphors such as “predator” and “trapped within the cage” paint her as a wild beast (as seen in Mahjabin’s opinion and authorial comments in Table 5). Her family members describe her using derogatory terms, including “cunt,” “moral cripple,” “foolish older woman,” “fucking wise,” and a “selfish monster.” These descriptions not only reflect her family’s negative views but also reinforce the idea that Kaukab is the primary source of familial chaos and emotional turmoil.

Kaukab’s views of her children and husband portray her as a secretive schemer, concealing things from those surrounding her. Table 6 provides textual evidence of mutual animosity in these relationships.

The Muslim Woman as Bewildered and Perplexed: A Victim of Alienation

Three female characters, Kaukab, Suraya (SCMLL), and Tara (SCBMG), share common mental traits: self-doubt, paranoia, and overthinking. They often engage in irrational self-talk and are presented in a detached narrator tone. Table 7 provides evidence of Kaukab’s perplexing personality. The other two characteristics are explored separately in relevant sections.

She often succumbs to temper tantrums stemming from biased overthinking and irrational beliefs. Aslam (2004) skillfully linked Kaukab’s frenzied outbursts to her religious and self-doubting thoughts. Her fixation is consistently on the West, while her deep remorse is directed toward Allah, the one God in Islam. She is portrayed as unwavering in her convictions, which leads to loneliness and misery. The frequent use of emotive words like “sob,” “alone,” “darkness,” “desert of loneliness,” and “empty” underscores this portrayal.

Kaukab is portrayed as someone trapped in the past and anxious about the future. However, the writer does not sympathize with her. Any sense of disappointment in her sad state is quickly dispelled as it implies that she is responsible for her situation. This characterization is achieved through authorial judgments and the opinions of other characters who see her as a nagging wife and a cynical mother. The phrase “everything she stood for” in Table 8 is significant. Through this authorial attitude, Kaukab is presented as a symbol of the Muslim world in the eyes of Aslam. She embodies the alienation experienced by Muslim women, particularly religious ones.

In Aslam’s view, Kaukab elicits the disdain that he believes every religious Muslim woman should receive. Her complex psychology, which shifts between intense attraction and aversion to the West, reflects a form of double consciousness, a concept articulated by W.E.B. Du Bois in The Souls of Black Folk (2008). This psychological struggle, characterized as unspeakable by other researchers like Amer (2012), leaves her torn between fears of appearing doubtful about Islam and a state of self-denial. Malpas and Davidson (2012) describe this mental state where minority members evaluate themselves through the lens of the Other.

Kaukab’s ambivalence toward modern Western society places her in a dichotomy, marked by “nagging anxiety over the inner contradictions of modernity and a radical skepticism toward the ideology of progress with which it is associated” (Malpas & Davidson, 2012). Table 10 notes her involuntary attraction to the West, a portrayal fittingly described in the discourse analysis as an eventuation and involuntary event (Van Leeuwen, 2008). The language used to depict her feelings of attraction, shame, or awe stemming from her sense of inferiority is highlighted in bold in Table 9.

Tara: An Oppressed Character of the Past, an Oppressor in the Present

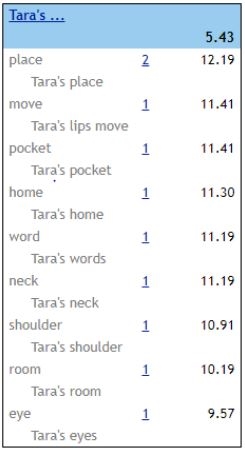

The name “Tara” is mentioned 184 times in SCBMG, often in possessive form with apostrophes. There are also metonymic references to Tara that use parts of her (see Table 10).

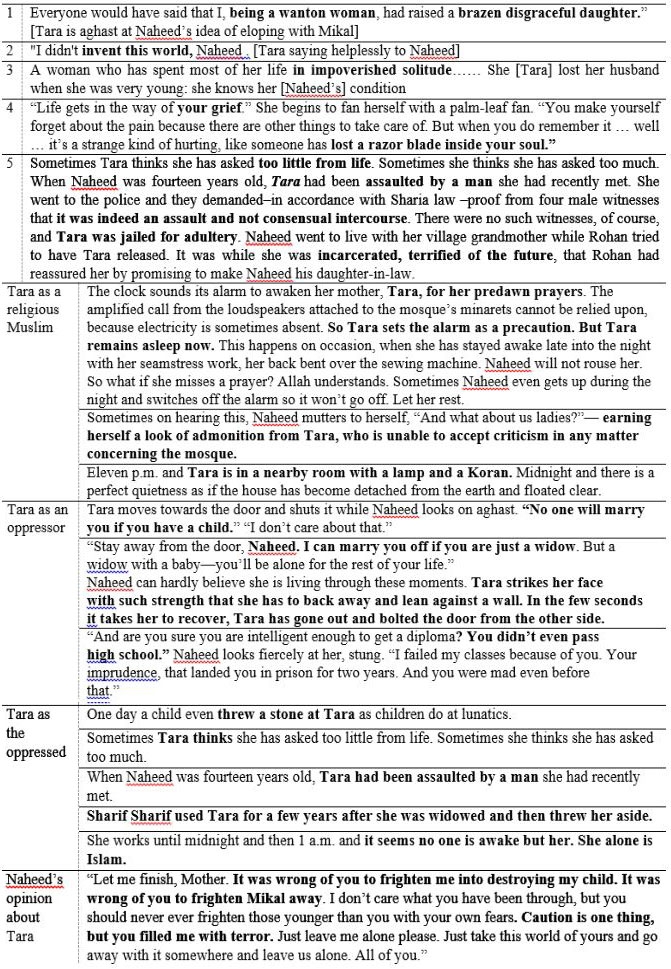

The concordance lines reveal Tara’s lifelong struggle against oppressive circumstances. She is portrayed as a widowed mother fighting poverty and patriarchal oppression within Muslim society.

Her most significant concern was marrying Naheed into a respectable family. Joe was her last hope as a son-in-law. In Naheed’s teenage years, despite being innocent, Tara faced a sexual assault and was imprisoned. This made her harsh and stringent. Tara forces her daughter Naheed to have an abortion because having a daughter reduces the chances of her second marriage. She did not want history to repeat itself. Tara herself is unable to marry again because of her daughter, Naheed. Aslam wants her to appear as a religious woman by frequently referring to her acts of worship. The last line in Table 11, uttered by Naheed, provides strong evidence that Aslam wants Tara to appear as a collective representation of Islam.

The Western “Prototype” of the Oppressed Muslim Woman

The term “Saracen” historically referred to Arabs and Muslims in Western literature. Scholars such as Kirner-Ludwig (2021) have studied this concept extensively in medieval English literary texts. This has evolved over time, as noted by Haddad (2007) and Hoodfar (1992). Kahf (1999) highlights two significant constructions: the “termagant” and the “odalisque,” depicting a transformation in the portrayal of Muslim women from feeble virgins to lascivious figures. Beckett (2003) explored the Western perceptions of Muslim women, particularly in Middle English Arthurian texts.

This one-dimensional Orientalist representation oversimplifies Muslim women’s diversity and complexity. Anglophone writers often claim insider knowledge, which further complicates problematic portrayals of Muslim women. Therefore, it is crucial to critically examine the stereotypical tropes introduced in this type of literature.

In Anglophone literature, Muslim households are depicted as gender-segregated spaces (Moghissi, 2005; Zayzafoon, 2005). The debates in the SCMLL and the SCBMG revolved around the unfulfilled desires of Muslim women. Recent Anglophone literature introduces two distinct categories of Muslim women in addition to the black Saracen warrior figure. These categories, termed “distressed demirep” and “salacious Saracen” in our research, encompass characters like Mahjabin and Sofia (distressed demireps) from SCMLL and Chanda and Naheed (salacious Saracen) from SCBMG. Suraya, also from the SCMLL, embodies a blend of these categories and can be termed a “distressed salacious demirep.” Across all these characteristics, Muslim women grapple with the conflict between their religious and natural needs versus their societal, physical, and psychological ones.

Mahjabin: Kaukab’s Scapegoat and the Distressed Demirep

Mahjabin often plays the role of a peacemaker in domestic conflicts involving Kaukab. She represents a stereotypically victimized Muslim girl pushed into early marriage by her mother. Despite enduring abuse, assault, and torture from her husband, her mother refused to consider the divorce justified, and Kaukab continually chastised her for obtaining one.

A notable parallel arises between Mahjabin’s character and the description of third-generation Anglophone writers, as outlined in an interview by Aslam(Chambers, 2011, p. 146). This generation serves as a bridge between parental traditions and the Western world. Interestingly, Kaukab’s discomfort with speaking English and her reliance on Mahjabin for medical appointments aligns with this portrayal (Chambers, 2011, p. 146).

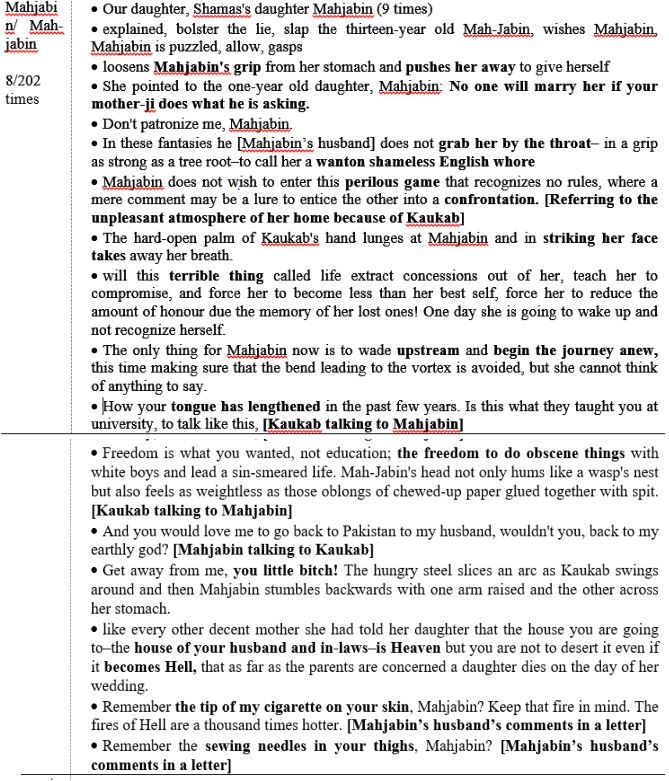

Mahjabin often bears the brunt of Kaukab’s intense arguments with her sons. Throughout the novel, she is predominantly identified in relation to Kaukab, referred to as “my daughter” and “your daughter.” Pronominal possessives are employed seven times to describe Mahjabin’s characters. Table 12 provides textual evidence from the SCMLL regarding Mahjabin’s portrayal in the novel.

Sofia: An apostate with strong moral values

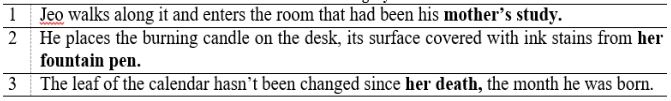

Sofia, Rohan’s deceased wife in the SCBMG, plays a crucial role in influencing all of Rohan’s family members, although she is no longer alive when the story unfolds. Her name is mentioned 39 times in the novel, but her presence is primarily conveyed through her impact on the thoughts of the other characters. Sofia is not depicted as actively participating in significant actions. The process types associated with Rohan differs from those associated with Sofia. Rohan endeavors to impart his teachings to his children and influence the world through speech and communication.

In contrast, Sofia is objectified by Aslam and portrayed as a vague yet compelling presence without direct engagement. Her enduring influence is conveyed through possessive somatization, a discursive strategy in which characters are indirectly referred to by associating them with a body part or something that belongs to them (Van Leeuwen, 2008, p. 47). This impersonalization adds an element of alienation, highlighting her passive yet glorified role in the discourse.

Sofia’s portrayal in the novel is predominantly associated with two settings: the garden that she paints and her deathbed. The narrative constructs the space around her using positively connoted words, evoking respect and pity from the reader. The initial word sketch of Sofia includes terms like “study,” “soul,” “paint box,” “crisis portrait,” “mistake,” “die,” and “death.”

The concordance lines reveal that her name sets her apart from other girls of her age and sociocultural background, thus individualizing her (Table 14). She stands out as a unique figure among her peers, pursuing a Master’s degree at Punjab University in Lahore. Sofia is depicted as having a refined taste in painting and calligraphy, a love for books, and the ability to instill a similar love for books among her children and students (lines 7-11, Table 14).

This individualization allows Aslam to showcase her exceptional qualities as a loving and faithful wife (lines 3-6), a scholarly achiever at the university (lines 1-2), and ultimately, a victimized apostate (lines 12-20, Table 14).

Aslam presented Sofia as a successful female student who achieved her education after rejecting the burka, a symbol of traditional norms. Even though she renounced the burka at her father’s insistence, her act still signified a rebellion against the convention. Father Mede refers to Sofia’s daughter, Yasmeen, as her mother’s daughter, emphasizing the continuation of Sofia’s legacy. Yasmeen is depicted wearing her mother’s tunic and wristwatch, underscoring this connection.

Sofia’s character is distilled by combining the generalization and abstraction of various practices. Her desire to establish the Ardent Spirit reflects her passion for education, while her refined aesthetic sensibilities earn her praise, particularly from individuals with discerning tastes such as Father Mede (lines 27 and 28, Table 14). These positive attributes justify her departure from Islam, despite her deep knowledge of the religion (lines 13, 15, 16, and 17, Table 14). These evaluative references align her with the principles of aesthetics and associate her with individuals who appreciated art, music, and literature. Such associations grant her role-model status and enhance the credibility of her moral, political, and religious judgments.

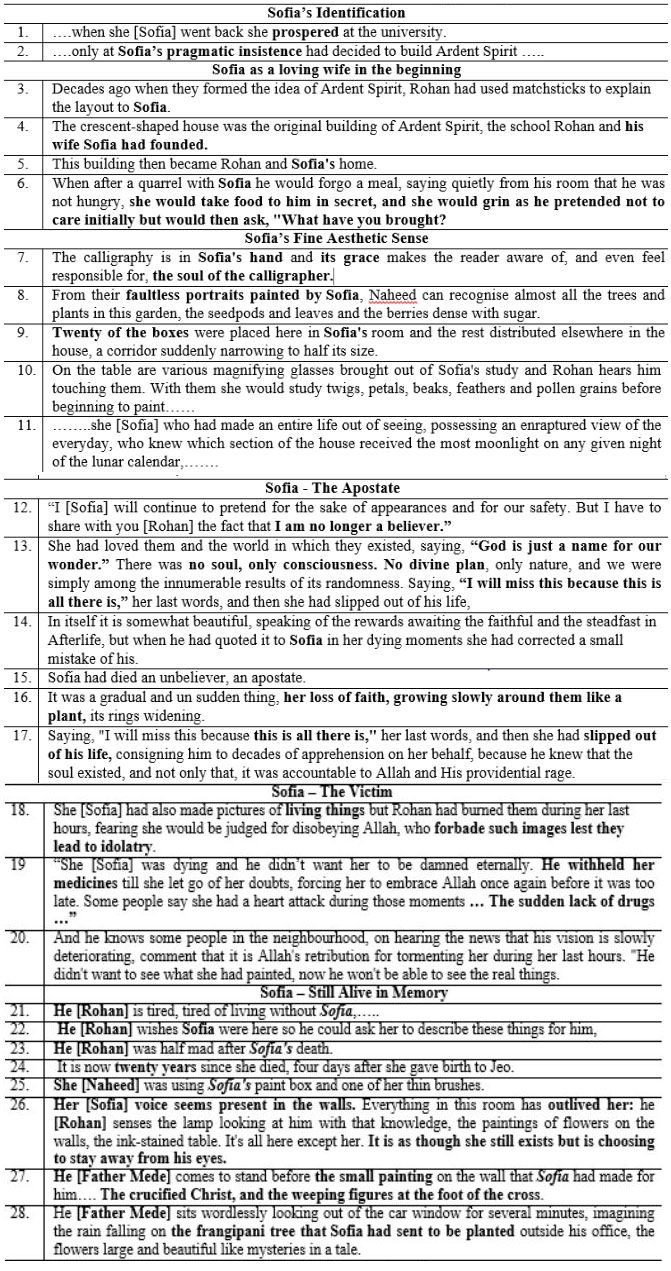

Ultimately, Sofia is depicted as a figure worth emulating, as both her children follow in her footsteps and reject their fathers’ staunch religious ideas. After her death, Rohan, Yasmeen, and Father Mede cherish her memory, indicating the writer’s positive appraisal (lines 21-29, Table 15).

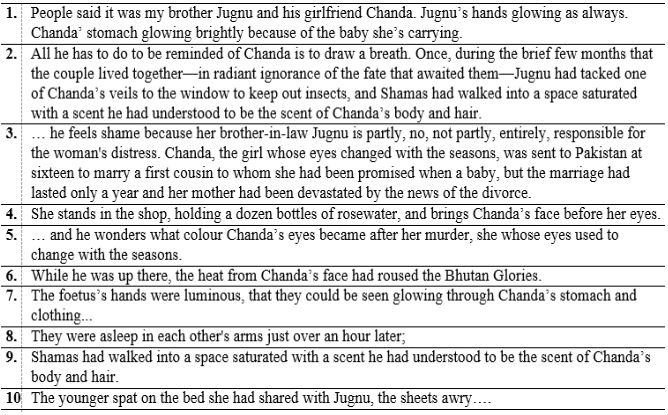

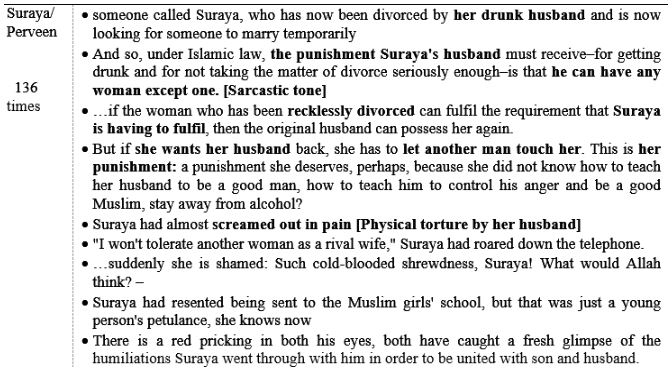

Chanda: The Captive Beauty Forced to Become a Salacious Saracen

In the SCMLL, Chanda embodies the archetype of the white Saracen. Despite enduring humiliation, threats, and abuse from her husband, she struggled unsuccessfully to obtain a legal divorce. Aslam portrays her as a poignant symbol of misery and powerlessness.

The author uses sexual imagery to describe Chanda’s illicit relationship with her lover, Jugnu. Phrases like “Chanda’s body,” “Chanda’s face,” “Chanda’s mouth,” and “Chanda’s veil” recur in the text, as depicted in Table 15. Like a white Saracen woman, Chanda must defy her father and brothers to be with Jugnu, a modern liberal Muslim man. Her character serves as a symbol deserving liberation from the oppressive, patriarchal Muslim males, exemplified by her brother’s derogatory name-calling of “bitches” and “whores.”

The three Muslim female characters from the SCMLL share traits reminiscent of beautiful, talented, and voluptuous Muslim women who find themselves ensnared by sinister and wicked Muslim men yet remain prepared to escape if the chance arises. These characteristics mirror those attributed to the captivating white Saracen women of medieval times.

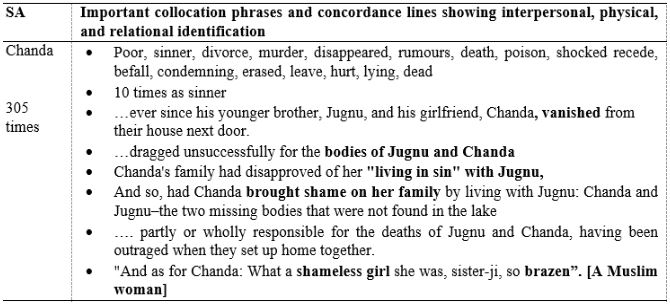

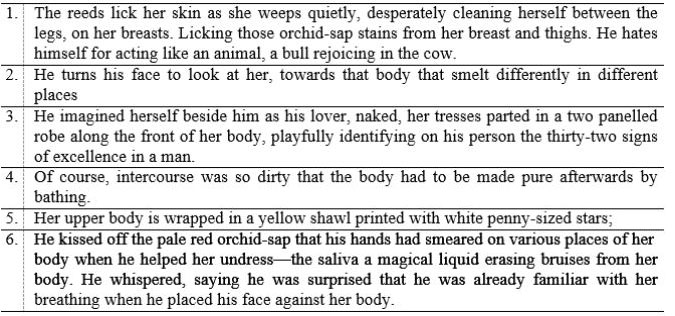

Suraya: Incarnation of the Lewd White Saracen

Suraya’s personality is an amalgam of contradictions as her public appearance differs entirely from her private persona. She is torn between Islam and her essential needs. After surviving a life of thrashing and abusive behavior by her husband, Suraya is divorced by him three times while he is drinking. Aslam portrays her suffering due to domestic abuse and religious oppression. She cannot reunite with her husband and son unless she marries another man and is divorced by this second man. She begins by alluring Shamas, who is already married, for this purpose. In a state of two-ness, she loathes and enjoys her illegitimate physical union with him (Table 17). Aslam often shows her in dialog with herself, asking Allah whether this humiliating punishment is meant for her or her husband, allowing him to pass many censuring remarks onIslamic system.

Suraya’s character embodies the recurring archetypes of victimized Muslim women often found in postcolonial literature. To attain salvation, Suraya must engage in a sensual extramarital relationship that aligns with the concept of white Saracen. Shamas assumes the role of the white/French savior, and their love is depicted through sensual imagery. Her portrayal of Shamas as an object of desire, combined with her suppressed circumstances, evokes sympathy from the readers.

Despite internal debates regarding the conflict between her actions and beliefs, Suraya is willing to conform to the desires of modern liberal Muslims, whether through intimate relationships or elopement. Her character resonates with the notion of the charming white Saracen, yielding to the demands of the white man.

Notably, to deserve the writer’s and target reader’s commiseration, like the white Saracen, Muslim woman must possess two qualities simultaneously (Ramey, 2001). First, the Muslim man must oppress; second, the Western lifestyle must be alluring to her (Ramey, 2001). The first condition is satisfied by creating an abusive drunkard husband and the second is by enticing her to have a physical relationship with Shamas. In the following section, we discuss how Naheed (SCBMG) satisfies these conditions.

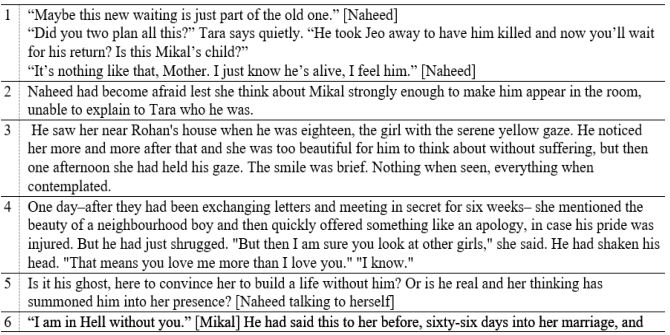

Naheed: The Aggrieved Temptress in SCBMG

Naheed was mentioned 222 times in the SCBMG. In Naheed’s word sketch, two prominent features emerge: First, she was predominantly associated with mental processes and portrayed herself as a perceptive and sentient individual (Table 20). This construction highlighted her sensitivity and emotional depth. Second, these processes allowed the writer to delve into Naheed’s inner thoughts and psychological experiences, thus providing insight into her character.

Another notable feature of Naheed’s word sketch is the frequent appearance of an apostrophes in her name, a possessive construction often associated with victimized characters. Considering these indicators, examining Naheed’s concordance lines reveals her portrayal in the following context.

In Aslam’s fictional world in the SCBMG, life is oppressive for Muslim characters, such as Naheed. She is coerced into marrying Joe only for him to leave her on the 66th day of their marriage to join the Afghan Jehad. After being widowed, she is advised by her mother to terminate her pregnancy, as it would diminish her prospects for a second marriage. Within this fictional realm, Muslim women with dowries are preferred for marriage over impoverished women, and girls as young as ten are forced into unions with much older men. The stark class disparities make it seem peculiar to how someone like Tara, a seamstress, managed to arrange her daughter’s marriage into an affluent household.

Numerous studies have pointed out the recurring Western “prototype” of the Muslim woman, often depicted as a captive beauty or a lascivious Saracen, created by the West to serve its interests (Moghissi, 2005; Zayzafoon, 2005). These scholars argued that Muslim women are frequently portrayed as symbols of unfulfilled desire. Western narratives, particularly in literature, tend to associate Muslim women in harems with notions of sexual despotism and sensuality (Hoodfar, 1992; Kahf, 1999). In presenting a Muslim woman as a counterimage to a Western woman, she is often portrayed as unhappy in her harem (Alloula, 1987).

In response to the prevailing post-9/11 images, the choices made to represent Naheed tend to cast her as a stereotypically oppressed Muslim woman in search of greater freedom. This aligns with the racist discourse against Muslims, wherein the white man assumes the role of savior. However, a subtle shift can be observed, replacing the white man of past representations, and aiding the Muslim captive beauty in fulfilling her sexual desires with a contemporary native figure. Table 21 provides textual evidence supporting these observations.

Van Leeuwen (2008) argues that positive evaluation is not always explicitly expressed linguistically expressed; rather, it often resides beneath the surface and needs to be inferred within the cultural context of social practice. Aslam’s choices in representation emphasize childhood suffering, unfulfilled desires, and Naheed’s role as a savior after Rohan’s blindness and Basie’s death while avoiding direct mention of the illegitimacy of their relationship. This distillation process accentuates one aspect of the practice at the expense of others, contributing to the legitimization of Mikal and Naheed’s relationship through evaluative associations. Some of these distillations involve abstracting the relationship and emphasizing the emotions involved, as shown in Table 21; these include waiting (line 01), intense thinking (line 02), contemplation (line 03), and experiencing profound distress (line 06).

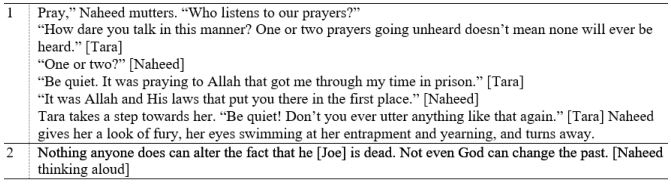

Resonance of Atheism and Disbelief toward Islam

The picture of a white Saracen is not complete unless a Muslim woman shows skepticism toward her religion and cultural norms. Naheed’s doubts resonate with atheism or, at least, agnosticism, and she is frequently found doubting Tara’s beliefs and openly blaming the Islamic system for her plight (Table 22).

Another recurring feature of Aslam’s fiction is the depiction of glorified or victimized female characters with atheistic beliefs and tendencies. The similarities between Tara and Kaukab are listed in Table 22. Kaukab is portrayed as a gullible individual incapable of persuading her children with rational arguments in favor of Islam, while Tara is similarly depicted as unable to provide logical explanations to dispel Naheed’s doubts (line 01, Table 22).

Radical Exclusion of an Inspiring Muslim Woman

“Erasure is a form of oppression–the refusal to see.” Chanel Miller (p.no 244, 2020)

After analyzing the six most frequently appearing female characters in the SCMLL and SCBMG, it becomes apparent that none of the Muslim female characters created by Aslam were inspirational women.

Conclusion

This article’s analysis of the SCMLL and SCBMG justifies the initial observation that Aslam reinforces the neo-Orientalist tradition by portraying Muslim women in negative roles. This time, the vilification of Muslim women involves the erasure of inspirational Muslim women from fictional worlds. This has resulted in the maintenance of Western women’s cultural superiority over their Muslim counterparts. Haddad (2007) posed the reasonable question that the liberation of a Muslim woman is always highlighted in colonial endeavors, but the answer to the question ‘Liberation from what?’ keeps changing with the changing demands of the masters. Puritans in the nineteenth century propagated the view that the Muslim woman was a victim of overindulgence in sex; the 20th century saw a shift of focus, and political rights and education were brought forth as excuses; at present, Aslam is playing with the representation of Muslim women by portraying her either as a miserable religious maniac, a salacious Saracen, or a captive beauty. The recurrent surfacing of extremely stereotypical and hardly relevant portrayals must be investigated in the works of other Anglophone writers, such as Shamsie, Hanif, and Hamid. Moreover, analyzing the positive portrayals of Muslim women alongside negative representations within the media and fiction can be profoundly beneficial for fostering a more inclusive and nuanced understanding of this diverse group. Exploring positive depictions, such as those in Leila Aboulela’s literary works (2015, 2018), can counterbalance harmful stereotypes and misconceptions, showcasing the richness and complexity of Muslim women’s lives, aspirations, and contributions. Due to space constraints, it is not feasible to incorporate other literary works into the scope of this article. Nevertheless, we recommend that the works of Aboulela, Shamsie, Hanif, and Hamid provide compelling avenues of study for future research.

References

- Aboulela, L. (2015). The Kindness of Enemies. United Kingdom: Hachette UK.

- Aboulela, L. (2018). Elsewhere, Home. London: Saqi Books.

-

Alloula, M. (1987). The Colonial Harem, 21. United Kingdom: Manchester University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctttth83]

-

Anderson, T. D., & Anderson, M. (2021). The erasure of black women. Journal of Critical Education Policy Studies at Swarthmore College, 3(1), 8–25.

[https://doi.org/10.24968/2473-912x.3.1.2]

- Aslam, N. (2004). Maps for lost lovers. Vintage New York City: Penguin Random House.

- Aslam, N. (2013). The blind man’s garden. London: Faber & Faber.

-

Bahramitash, R. (2005). The war on terror, feminist orientalism and orientalist feminism: Case studies of two North American bestsellers. Critique: Critical Middle Eastern Studies, 14(2), 221–235.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/10669920500135512]

- Belloc, H. (1913). The Servile State. Edinburgh: Neill and Co., Ltd., Edinburgh.

-

Beckett, K. S. (2003). Anglo-Saxon perceptions of the Islamic world (Vol.33). United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511483233]

- Boehmer, E. (Ed.). (1998). Empire writing: An anthology of colonial literature 1870-1918. Oxford: OUP.

- Bly, S. M. (2002). Stereotypical Saracens, the Auchinleck Manuscript, and the Problems of Imagining Englishness in the Early Fourteenth Century. Ann Arbor, Mich. : University of Notre Dame.

-

Cahill, S. A. (2019). Intelligent souls? Feminist orientalism in eighteenth-century English literature. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.36019/9781684481019]

- Chambers, C. G. (2010). Multi-culti, Nancy Mitfords and halal novelists: The politics of marketing Muslim writers in the UK. Textus: English Studies in Italy, 23(2), 389–403.

-

Chambers, C. (2011). A comparative approach to Pakistani fiction in English. Journal of Postcolonial Writing, 47(2), 122–134.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/17449855.2011.557182]

-

Cooke, M. (2007). The Muslim woman. Contemporary Islam, 1(2), 139–154.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s11562-007-0013-z]

-

Cooke, M. (2008). Deploying the Muslim woman. Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, 24(1), 91–99.

[https://doi.org/10.2979/fsr.2008.24.1.91]

- Du Bois, W. E. B. (2008). The souls of black folk. New York: Oxford University Press.

-

Haddad, Y. Y. (2007). The post-9/11 hijab as icon. Sociology of Religion, 68(3), 253–267.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/socrel/68.3.253]

- Hoodfar, H. (1992). The veil in their minds and on our heads: The persistence of colonial images of Muslim women. Resources for Feminist Research, 22(3/4), 5-18.

- Kahf, M. (1999). Western representations of the Muslim woman: From termagant to odalisque. Texas: University of Texas Press.

- Khan, A. B., Pieper, K. M., Smith, D. S., Choueiti, M., Yao, K., & Tofan, A. (2021, June). Missing & maligned: The reality of Muslims in popular global movies. USC Annenberg, 1–37.

-

Kirner-Ludwig, M. (2021). ‘The Wickede Secte of saracenys’ – lexico-semantic means of strengthening the English Christian self in texts from the Middle English period. SELIM. Journal of the Spanish Society for Medieval English Language and Literature, 26(1) 57–84.

[https://doi.org/10.17811/selim.26.2021.57-84]

-

Král, F. (2009). Critical identities in contemporary Anglophone diasporic literature. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

[https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230244429]

-

Král, F. (2014). Social invisibility and diasporas in Anglophone literature and culture: The fractal gaze. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

[https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137401397]

-

Lau L., Mendes A. C. (2012). Re-orientalism and South Asian Identity Politics: The Oriental Other Within. New York: Routledge.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203814543]

- Maalouf, A. (2012). The crusades through Arab eyes. London: Saqi Books.

- Malpas, J., & Davidson, D. (2012). Metaphysics. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved April 15, 2022 from https://plato.stanford.edu/

-

Meer, N. (2014). Islamophobia and postcolonialism: Continuity, Orientalism and Muslim consciousness. Patterns of Prejudice, 48(5), 500–515.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/0031322X.2014.966960]

-

Meer, N. (2018). ‘Race’and ‘post-colonialism’: Should one come before the other?. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 41(6), 1163-1181.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2018.1417617]

- Miller, C. (2020). Know my name: A memoir. United Kingdom: Penguin.

- Moghissi, H. (2005). Women and Islam. Vol. 3 : Women’s movements in Muslim societies. London: Routledge.

-

Mukherjee, A. P. (1990). Whose post‐colonialism and whose postmodernism? Journal of Postcolonial Writing, 30(2), 1–9.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/17449859008589127]

- Namaste, V. K. (2007). Invisible lives: The erasure of transsexual and transgender people. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Ramey, L. T. (2001). Role models? Saracen women in medieval French epic. Romance Notes, 41(2), 131–141.

-

Said, E. W. (1985). Orientalism reconsidered. Race & Class, 27(2), 1–15.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/030639688502700201]

-

Santesso, E. M. (2013). Disorientation: Muslim identity in contemporary Anglophone literature. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

[https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137281722]

- Sims, J. (2017). The Matilda effect. The School Librarian, 65(4), 232–232.

-

Speed, D. (1990). The Saracens of king horn. Speculum, 65(3), 564–595.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/2864035]

- Squires, C. (2012). Too much Rushdie, not enough romance? The UK publishing industry and BME (Black Minority Ethnic) readership. In J. Procter, B. Benwell & G. Robinson (Eds.), Postcolonial Audiences: Readers, Viewers, Reception. Routledge Research in Postcolonial Literatures (pp. 99–111). Abingdon: Routledge.

-

Squires C. (2013). Literary Prizes and Awards. In Harper G (Ed.), A Companion to Creative Writing (pp. 291-304). Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118325759.ch19]

-

Van Leeuwen, T. (2008). Discourse and practice: New tools for critical discourse analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195323306.001.0001]

- Zayzafoon, L. B. Y. (2005). The production of the Muslim woman: Negotiating text, history, and ideology. Lanham, Md: Lexington Books.

Biogrpahical Note: Dr.Azka Khan is working as Assistant Professor at Rawalpindi Women University. Her published research spans digital humanities, corpus-assisted discourse studies, postmodern literature, and translation studies.

Biogrpahical Note: Dr. Sarwet Rasul is a Professor of English and the Dean of Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Fatima Jinnah Women University, Rawalpindi. Author of more than fifty research papers, she has various national and international projects to her credit.

Biogrpahical Note: Ramsha Khan an English lecturer, passionately combines her academic background with a research interests in narratology and corpus stylistics, delving into the interplay between narrative structures and linguistic elements in literature.