Shifting Patterns of Care for Elderly Women in the Changing Matrilineal Society of the Minangkabau, Indonesia

Abstract

This study discusses the shifting patterns of care for elderly women in the changing matrilineal society of Minangkabau, West Sumatra, Indonesia. The Minangkabau are the most populous matrilineal culture in the world. One crucial characteristic of Minangkabau society is its communal and woman-centered family structure and women have special rights that protect them within the family and the community. However, this traditional ideal must be questioned, given the current tendency for women of advanced age to be placed in care homes for the elderly. Why are the special rights of women in their communities seemingly not applicable to the elderly? This study finds that the increased use of elderly care homes is a logical consequence of a significant transformation in the matrilineal culture of the Minangkabau. Changes in power relations, social categorization, and social structures justify the placing of elderly women in care homes. The traditional infrastructure has eroded over time, and the values and symbols of the past are no longer protected. In other words, placing elderly women in care homes is a logical consequence of unavoidable structural changes.

Keywords:

Elderly women, elderly care, social change, matrilineality, MinangkabauIntroduction

The recent change in Minangkabau society, Indonesia, whereby the elderly are increasingly sent to care homes rather than remaining at home with their families, has challenged this society’s woman-centered matrilineal traditions. Minangkabau women traditionally have special authority and positions within their families (Blackwood, 2001; Hakimy, 1984). They have enjoyed control of houses, heirlooms, inheritances, and other places of residence that have been determined matrilineally, and women vote in family and community discussions. However, the period around the 2000s saw an increasing demand for placing the elderly in nursing homes in West Sumatra after the government established such a service in the early 1980s through a program at the Ministry of Social Affairs. The two government-owned care homes for the elderly in different locations are called “nursing homes.” Elderly people who are accepted are supported free of charge because the service is intended for elderly people without sufficient means. There are also two nursing homes managed by the private sector; these charge maintenance fees, although they are not large because the management also tries to find donors willing to help cover monthly operational costs.

The increasing interest in nursing homes indicates that the position and power of women in family life among the Minangkabau ethnic group is becoming questionable. This statement applies to families who place their family members in nursing homes, reflecting a change in the support offered to women after reaching old age. They no longer live in their own homes and are not cared for by their families or children. This suggests a need to review the strategic position of women in Minangkabau society today.

Data from the Department of Social Affairs, West Sumatra, Indonesia, indicates that 56.9% of the occupants of the region's two government-managed nursing homes are women (Dinas Kesehatan Provinsi Sumatera Barat, 2016). The high percentage of women in the homes is a new phenomenon that has only developed in recent decades and may be seen as an indicator of a significant shift in the matrilineal Minangkabau society, which will affect elderly care in this region. Some studies have examined this phenomenon in the context of modernity, which has driven a change in residential patterns from the traditional rumah gadang (“big house”) to smaller houses (Blackwood, 2000), or have investigated if this tendency stems from the privatization and fragmentation of communal lands (Prastiwi Andar, 2020; Tegnan, 2015). Similarly, the Minangkabau tradition of merantau (migration) has been suggested as a source of change that affects elderly care. Merantau is the term applied when a person moves to an area outside their hometown in search of a better life (Mukhneri, 2017; Naim, 1971). Arguments regarding the shift in elderly care patterns from families to elderly care homes must be evaluated within the context of such changes.

Explanations of changes in patterns of elderly care have yet to consider micro-subjective factors, particularly within women's traditional positions such as bundo kanduang. (which refers to Minangkabau women with a central role in Minangkabau society). This article aims to explain how changes in the care of elderly women have resulted from sociocultural transformations in the matrilineal Minangkabau society of West Sumatra, Indonesia, and the factors that caused this change. Do these shifts in care patterns signify changes in the concepts, values, and symbols of Minangkabau society, particularly regarding women?

The current study aims to answer this question by mapping the changes in the forms and practices of elderly care as experienced by women in Minangkabau society, the cultural transformations that have underlain these changes, and social attitudes toward these changes in care for the elderly. Such an analysis is critical because these evolutions in elderly care patterns have emerged due to fundamental transformations in the matrilineal traditions of Minangkabau society.

Such changes have not always ignored women's subjectivities, and women can be directly involved in the transformations within their communities. Subjectivity is considered a significant factor in women's life choices. They are not always objects of change; they may also act as actors in the structural and cultural transformations of their societies, as reflected in these changes in elderly care. Institutional modifications may also occur as the Minangkabau community responds culturally to modernity.

This research can be seen as original and novel because research on elderly care in the context of matrilineal cultural transformation remains limited. To date, such research has been in relation to models of elderly care in nursing homes, problems in elderly care (Andel, Hyer, & Slack, 2007), quality of life for the elderly (Giang et al., 2019) and elderly care and cultural factors (Dilworth-anderson, Pierre, & Hilliard, 2012; Naldini, Pavolini, & Solera, 2016). However, this study highlights that the presence in matrilineal communities of nursing homes housing elderly women is a paradox, and may therefore be evidence of support for elderly women being neglected and the waning power of women.

This research was conducted on the Minangkabau community, the ethnic group that is the largest stakeholder in the matrilineal system and that has complex traditional instruments to protect elderly women. However, the increasing numbers of elderly women now in nursing homes can be seen as an early warning and requires us to define and reconstruct the existence of the Minangkabau matrilineal system. This study therefore presents a critical discourse from a sociological perspective on assisting the elderly in a society that adheres to a matrilineal system.

Literature Review

Elderly Care and the Choice of Elderly Care Homes

Advanced age is marked by physiological, psychological, and social changes (Leslie & Hankey, 2015). Physically, it leads to loss of muscle mass, increased body fat, physical weakness, limited physical activity, and a reduced resting metabolism (McLean & Kiel, 2015). Elderly people are more vulnerable to injury than other age groups, and therefore require assistance and care in their everyday activities. Every elderly person requires physical, psychological, spiritual, and social service as well as guidance. The means by which these needs are fulfilled are determined both socially and culturally. In other words, various responses to aging, including elderly care, are part of a society's sociocultural choices. However, each country and culture has specific indicators that define old age. In the context of this study, people over 60 years of age are referred to as “elderly” based on Law No. 13 of 1998 concerning Elderly Welfare (Bappenas RI, 2020).

Anne Leonara Blaakilde (2001) has shown how the misery narrative has colored debate over the elderly and elderly care, even though there is significant evidence that the elderly can have happy lives as they prepare to transition to the afterlife. Such narratives also fail to illustrate the unique subjectivities of women in their individual and social preparations for the afterlife. Based on this assumption, it is necessary to understand the basis for transformations in elderly care, the connections between the elderly and their families and communities, and their autonomy in decision-making.

Researchers have found that dementia is a significant factor in determining the placement of the elderly in care homes, noting that 80% of adults aged 65 years and older have at least one chronic health problem (Andel et al., 2007). This fact influences life and care patterns within families. In this context, it is necessary to consider which environments are appropriate to the needs, desires, and habits of the elderly to ensure their quality of life (Hansen & Gottschalk, 2006). Where standards of care at home are lacking, elderly care homes are considered a solution. In these care facilities, for example, the nutritional needs of the elderly can be met (Buckinx et al., 2017), thereby avoiding the common problem of malnutrition.

The Elderly in the Family and Community

As individuals enter advanced age, their families remain their basic social unit and help them satisfy their needs, both physical needs such as food and shelter and social needs such as love and acceptance (Huitt, 2004). Families can help improve the psychological welfare of the elderly and reduce their stress levels.

Frequently, the elderly are seen as nurturers of their grandchildren, and through them, other family members may also find love and nurture (Giang et al., 2019). Simultaneously, the elderly seek to give meaning to themselves through their children and grandchildren. Many studies have found that filial piety, including family values, influences how the elderly live. Orientation toward family values can be seen through families' allocation of love, the lack of which may be why many individuals do not feel at home in elderly care homes (Saarnio, Boström, Hedman, Gustavsson, & Öhlén, 2017). Family bonds may therefore significantly influence the treatment the elderly receive from their families.

Psychological issues, such as depression, are quite common among the elderly and influence how they live. Adjustments are essential for client comfort in elderly care homes. Wreksoatmodjo (2013) found that visits to such homes can significantly influence mental health, as visits from family members and friends provide the elderly with significant emotional support, separation from family being a common fear among those in nursing homes. However, at the same time, it is also common for the elderly to consciously choose to live apart from their families to ensure greater privacy and peace.

Community and social bonds are essential factors that influence the quality of life enjoyed by the elderly. In other words, social relationships and interactions within a specific community determine its continued survival (Rapaport Lurie, Cohen, Lahadeg, & Limor Aharonson, 2018). In this context, elderly care homes may be seen as communities in which members support and help each other during the remainder of their lives. Existing studies have emphasized the need to understand such homes as families or communities that include specific emotional bonds. Simultaneously, these care homes offer specific environments, including appropriate food, that may improve quality of life. Shared understanding and individual and community perceptions can create a sense of trust, provide a collective identity, and improve sharing (Abrams & Hogg, 2001), because of such considerations, clients and their families may consciously choose elderly care homes.

Research Method

This study combines quantitative and sequential qualitative approaches in a mixed method design. The quantitative approach is on equal footing with the qualitative approach, which complements and enriches the understanding of the shift in support institutions that occur in Minangkabau families who have placed their elderly family members in nursing homes. The quantitative approach is positioned as an initial approach to collecting data on elderly people who are supported by institutions and this data is then used as a basis for a qualitative approach. The quantitative approach focuses on the lives of the elderly before and while in the nursing home, as well as the reasons why responsibility for their care shifted from the extended family to the nursing home. This was achieved by conducting a survey of those elderly in nursing homes used as research locations. A qualitative approach was used to describe the characteristics of elderly people's lives, their conditions before moving to an institution, conditions while living in that institution, and their views about life there. The data produced using these two approaches were then analyzed in terms of shifts in elderly care practices.

The study was conducted in two steps. First, an extensive survey was carried out in two elderly care homes: Sabai Nan Aluih in Sicincin, Padang Pariaman Regency, home to 110 men and women, and Kasih Sayang Ibu in Cubadak Batusangkar, Tanah Datar Regency, home to 70 men and women. These two homes are owned and funded by the regional government. Of the 180 residents, 97 (53.4%) were women. Questionnaires were distributed to 31 elderly women, several of whom were later chosen for interviews. These women were selected based on their Minangkabau heritage and their health.

The second step was to use the data from the survey results to delve deeper into the question. In-depth interviews were conducted with 25 interviewees, including representatives of five elderly women and their families, selected based on an analysis of their survey responses. The variables considered were the number of children, family financial situation, and subjective desire to receive elderly care at home. In-depth interviews were also conducted with several social leaders, with data from these interviews used both for analysis and to obtain a deeper understanding of the research problem, namely, the effects of social transformations in Minangkabau society on elderly care patterns.

Research Findings

Care Patterns for Elderly Minangkabau Women in Nursing Homes

Women play an important role in the social and cultural structure of the Minangkabau ethnic community in Western Sumatra, Indonesia. The Minangkabau are one of the few ethnic groups in the world that adhere to a matrilineal system in which women determine their lineage and have the power to be reckoned with in society. Women are also owners of the rights to large family inheritances, including land and houses, so they can expect a proper place and support from their family in their old age. However, over the last 20 years, this has changed. Many women are no longer accorded a position in the family in their old age, as they are considered a burden and are neglected. This has led to an increased demand for nursing homes in Western Sumatra as institutions that can assist these elderly women.

The change in care for the elderly from families to nursing homes has not been caused by a breakdown of the matrilineal system in Minangkabau. However, there have been some changes in that system, notably a weakening of extended family ties, and especially so among families that place their elderly family members in nursing homes. Ideally, in Minangkabau culture, living in an extended family system is the core of a matrilineal family (Hartati, Minza, & Yuniarti, 2021).

Every woman, including the elderly, is subordinated to being part of a family that lives in a communal and collective spirit supported by shared ownership such as the rumah gadang, the clan's inheritance, and the penghulu kaum (chief of lineage) as the clan leader. However, traditional elements have changed, and this includes the concept of family, which has shifted from an extended to a nuclear family.

Changes in the matrilineal system in Minangkabau society have occurred evolutionarily as a consequence of the culture of merantau (migrating) and the latent impact of modernization and globalization. Interaction with knowledge from foreign cultures has changed the Minangkabau generation understanding of local cultural values, such as the principles of kinship, collectivity, and responsibility. This includes responsibility for elderly care, which was previously the full responsibility of the family but is now starting to shift to nursing homes. This shows that the shift in the institutions of care for the elderly from extended families to nursing homes in some Minangkabau communities is a form of flexibility in the Minangkabau culture to modify and adapt to various external influences coming from outside.

Elderly care homes in West Sumatra were established using a top-down approach implemented by the Department of Social Affairs in the 1980s. The increasing number of nursing homes in the Minangkabau community is based on the growing needs of the community due to the number of elderly requiring care outside their families. In the early years of their founding, they were not readily accepted by community leaders, who perceived them negatively. However, despite this, nursing homes have survived and developed significantly. Today, opposition to and negative perceptions of elderly care homes are rarely heard, and they appear to have been accepted by Minangkabau society. The head of the Sabai Nan Aluih Nursing Home stated:

From my recent observations, since 2000, the strong reaction of community leaders regarding the reason for bringing in their elderly family members to be cared for in elderly care homes has become feeble, and they consider it a matter and decision for the respective families. (Interview, July 15, 2022).

This statement is in line with the view of the mayor of the Padang Pariaman Regency:

The community is becoming more realistic; we from the Nagari government can only allow it if there is a request for a letter of recommendation to receive support at elderly care homes. Many elderly people living in villages have been neglected. There was no one to care for or provide for their needs. Family members from more distant relatives are already busy with their affairs, and their average standard of living is also poor. (Interview, July 23, 2022).

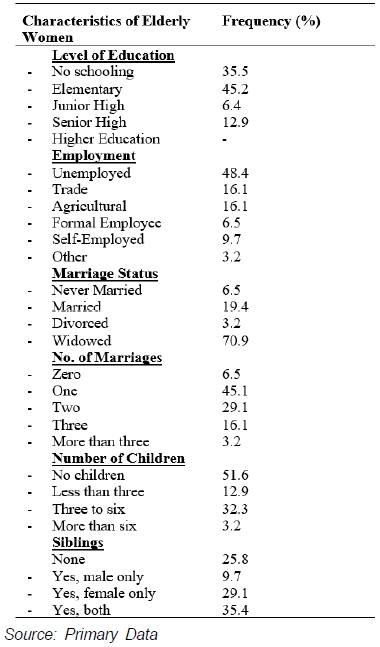

These statements show that the shift in the pattern of elderly care in the Minangkabau community occurred because of the need to ensure the welfare of the elderly where it was being neglected by the family. This can be observed in the data gathered from the elderly and presented in Table 1.

Table 1 gives information about the circumstances of the elderly women interviewed in this study, including their relatively low level of education and their economic dependence on productive-aged family members. Their marital histories indicate that while some never married, the majority are widows. This suggests that most respondents lived independently and relied on assistance from their children and other family members.

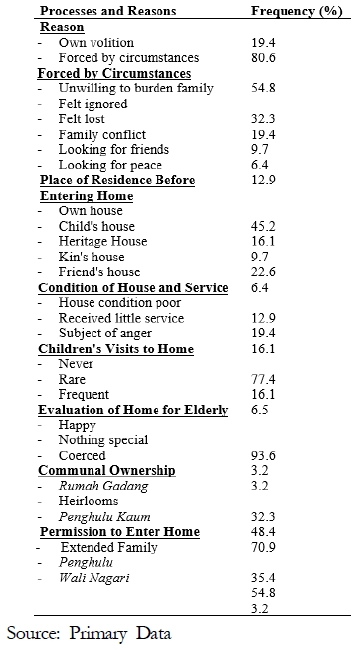

Most interviewees stated that they had sought care in a nursing home because circumstances forced them. The desire to avoid burdening their families was the dominant reason, and was linked to their families' limited financial capacity (see Table 2). Family poverty is not only a factor that may drive elderly women to seek nursing home care, it is also a criterion for entering government-run homes. This is illustrated by Mrs. RSM, an elderly woman living in the nursing home. According to her:

“I entered this elderly care home because of these circumstances. Previously, I lived with a daughter with five children whose husband worked as an elementary school caretaker. We lived together in cramped and uncomfortable elementary school caretaker’s accommodation. When my daughter or her husband scolded their children, I felt like I was being scolded by them myself. When I received information about elderly care at the nursing home, I secretly looked for a way to move there (Interview on August 12, 2022)

Other factors that could potentially drive women to seek elderly care outside their family home include dilapidated residences, limited receipt of care at home (i.e., required to wash their clothes), and violence/disrespect by family members. Almost half of the respondents presently receiving elderly care at exceptional homes had previously lived in their own houses.

Although economic factors and negligence are among the causes of changes in the care of elderly women and the increasing use of nursing homes, they are not the only factors. Other key factors relate to the transformation of the cultural system of Minangkabau matrilineal society. The shift in the family system from the extended to the nuclear family, the impact of the culture of merantau, and changes in ownership patterns of communal land and the move from rumah gadang to smaller houses have led to a decline in the power of Minangkabau women. This change has affected the responsibility of caring for the elderly, which has shifted from the extended to the immediate family. This becomes a problem for elderly people who do not have children or elderly people who are neglected in their nuclear families.

Homes for the Elderly and Elderly Women: Between Sponsorship and Fading Power over Inheritance

The transition of care for elderly women in Minangkabau from a rumah gadang to a nursing home is an indicator of the waning economic power of Minangkabau women. The rumah gadang and other family possessions are central to their power and if jurisdiction over them is lost, Minangkabau women would lose control and this could impel elderly women to seek care elsewhere (see Table 2).

The practice of asking their families rather than the penghulu kaum (chief of lineage) for permission to live in an elderly care home also indicates the decreased role of the kaum (extended family) as the main foundation of the matrilineal system. The decision to seek a place in a home is made through discussions with family members, both nuclear and extended. The need for such discussions indicates limited social cohesion within families.

Interviewees indicated that they were happy to live in an elderly care home and most suggested that they no longer wanted to live with their families. Most also preferred to be buried at their care homes, indicating the extent of the distance that has been created between themselves and their past, despite being part of matrilineal families.

When women seek care in nursing homes, it can be surmised that the power of their traditional culture has been eroded. Extended families can no longer guarantee their members safety and security. The rumah gadang, a symbol of the extended family, is seen as inefficient and requiring too much upkeep. Communal land (tanahulayat) is similarly no longer able to maintain the bonds within extended families, and the penghulu kaum can no longer protect family members (Ikhwan, Barlian, & Syah, 2023). Kinship relations are built based on a mutual understanding of the family’s actual conditions, as stated by a more distant relative of the informant, Mrs. RSM:

Relationships within the extended family are mutually understandable because family life is, on average, difficult. If there is a celebration, we will help as much as possible, and if there is no material, we can only use our energy and thoughts. (Interview on August 12, 2022)

However, receiving care in an elderly care home does not mean that women forget their families; some women may return to their family homes either temporarily or permanently, perhaps for fear of contracting a communicable disease or simply because they feel like doing to. However, women are rarely invited by their children to return to their family home, even though, during visits, administrators frequently urge family members to bring their relative home with them.

In this regard, some families firmly state their unwillingness to have the elderly live in their homes (again), viewing it as most beneficial for them to live in an elderly care home. This indicates that members cannot provide the necessary care or may be unwilling to have their comfort disturbed because of the need to provide care. Other reasons for families not bringing the elderly home include the following: (1) living in an elderly care home is what the woman desires, and thus she does not need to return home; (2) the woman appears comfortable living in an elderly care home and thus should not be brought home to a small, crowded house; and (3) nobody at home could care for the woman. This third reason indicates a perception of elderly women as an undesirable burden.

Families may or may not be willing to accept such women into their homes; however, they are generally not sure that the women would be ready to join them. The main reason they want to stay in the elderly care homes is that they already feel “distant” from their previous life within their family, as stated by YM:

Why would I expect to live outside the elderly care home again? I used to live with the family of my adopted child, who we raised at a young age. While living with them, Mother felt lonely. In this elderly care home, Mother has many friends of the same fate, the mosque is also close by for worship, and the elderly care home manager provides food. Let Mother wait for death to pick her up at this elderly care home. (Interview on June 4, 2022)

Some walinagari (village heads) who disapprove of elderly care homes cite a normative understanding that families are the ideal elderly caregivers. They do not recognize societal changes and argue that religious and customary teachings do not provide for such a care regimen. They believe that all matters can be resolved through traditional mechanisms and discussions. Meanwhile, other walinagari focus more on what is best for elderly individuals themselves rather than on normative values. Some approve of elderly care homes, but with some caveats, including the situation of the elderly themselves. If an elderly individual lives alone, seemingly abandoned by family, it is best for that person to enter an elderly care home. This reflects the tendency of the Minangkabau people to find normative and practical solutions.

Nursing Homes as a Form of Social Reproduction and a Weakening of Social Solidarity

The shift in elderly care from extended families to government-run homes can be seen as part of the dynamic of Minangkabau society, including its social acceptance of the change. On the one hand, shifts in elderly care may be seen as deviating from ideal behavioral patterns; on the other, this shift may be seen as a consequence of long-term transformations in Minangkabau society.

Over time, women, including those with family problems, have come to perceive elderly care as desirable. However, many elderly women in these homes rarely receive visits from their families, including their children, and some have never received any visits since becoming residents. In such cases, their presence in elderly care homes appears to be a means of relieving the burden on their families. One common reason elderly women are placed in care homes is the limited financial capacity of their children.

While receiving care, some women are actively involved, refusing to be treated as passive objects. These women take care of themselves and may even have chosen to enter a care home without previous discussions with their extended families or the penghulu kaum. As cultural actors, these women can distance themselves from the cultural expectations of collective decision-making. By entering elderly care homes, they can redefine their social positions and reject the traditions that dictate how they live. Such facts prove that the social solidarity of the Minangkabau people has begun to shift and concern for the welfare of elderly family members has decreased.

The position for men differs somewhat in this respect, as in the matrilineal Minangkabau society they occupy a vulnerable position; this is particularly true for widowers, who are expected to remain within their matrilineal family structure and live in a surau (prayer hall). This vulnerability is worst when men have no daughters. If they have no children at all and their wives have died, men must make a difficult decision: will they return to their extended families, remarry (although this may not resolve the situation), or live alone and face psychological isolation (Endrizal, 2006). Living in a surau after becoming a widower is similar to living in an elderly care home. Indeed, this institution may be viewed as a prototypical care facility within the Minangkabau social system. This differs significantly from the situation experienced by women, whose lives and security are supposedly guaranteed within the matrilineal system owing to their control of their extended family’s inheritance and rumah gadang (Reenen, 1996).

It is essential to consider the growth in elderly care homes within the context of the social transformations occurring in Minangkabau society. They have become “magnets” for change in elderly care. Initially, they were poorly understood by the communities. Over time, they have become known as alternative places where elderly women with social problems can receive care. These women feel more comfortable and safe in these facilities, and their food, shelter, and healthcare needs are guaranteed. At elderly care homes, they can pray solemnly and interact with other elderly individuals. This is one reason why many elderly women are happy to live in care homes and, conversely, unwilling to live with their families.

Over time, elderly care homes have come to be perceived in West Sumatra as an alternative for women with difficulties within their families and communities. They have positioned themselves as, “actors” capable of making conscious choices and undertaking actions to abandon the matrilineal structure and create new chapters in their lives. When the social and kinship system limits their individual freedom, women can gather new information and become more aware of how these facilities can meet their needs.

Discussion

The shift in care patterns is part of the social development of Minangkabau society, where extended families have long wielded collective power. Furthermore, social transformation cannot be separated from the tradition of rantau (migrated land), which shows the openness of the Minangkabau people to social change and alternative economic models. Similarly, shifts in managing family resources have affected the control and ownership of traditional assets such as communal land, thereby affecting family structures. Culturally, Minangkabau society is bound by the collective ownership of specific aspects, namely, heirlooms and rumah gadang. Extended families are defined by their shared ownership of a single rumah gadang, heirlooms, and a sense of togetherness. The erosion of this sense of togetherness has also affected the ability of extended families to provide care for elderly female members.

The tendency to live in tiny houses built for nuclear families has created a new culture that promotes privacy and individual ownership. These structures differ significantly from rumah gadang, which are public spaces used communally by the extended family that seek to encompass all members. The tiny houses built for nuclear families serve to create a “personal space” which other members cannot easily enter. This affects those family members who “happen to be living” with these families.

Communal land, heirlooms, and rumah gadang have been essential instruments for maintaining the Minangkabau’s matrilineal kinship system. They have also been perceived as part of extended families' identities and “spirits,” creating cohesion between members of the kaum. The “collapse” of the rumah gadang is not only linked to the erosion of women's “trump cards,” to borrow a term from Reenen (1996), but also brings into question the survival of the extended family system itself, particularly the tradition of providing material aid to members. These “trump cards,” despite having previously provided Minangkabau women with a social safety net, are no longer used in practice. The rumah gadang, a symbol of the Minangkabau matrilineal system, has traditionally functioned as the residence and administrative center of the saparuik (the members of matrilineal lineage). According to Radjab (1969), the Minangkabau traditionally lived in rumah gadang to ensure that all members of the saparuik could be monitored by the penghulu.

Ideally, poverty is not a reason to place elderly people in nursing homes if the social protection system in the form of concentric circles is functioning. Minangkabau society adheres to the principles of communal and collective life; each family member is protected by collectiveness, starting from the samande circle, namely, the group of relatives of one grandmother, also known as the matrilineal nuclear family. If the samande family to which they belong becomes extinct, the elderly must be supported by the saparuik family, namely, the group of relatives of one niniak (grandmother’s lineage group). If a niniak family also becomes extinct, the elderly person should be supported by the sepayung family, which is a group of relatives consisting of a combination of several saparuik families. If this also becomes extinct, the sasuku family, a group of relatives consisting of a combination of several sapayuang families, is obliged to provide support (Figure 1).

With this support pattern in the form of concentric circles, no elderly individuals should be neglected, even if they are poor. Moreover, there is a principle of the traditional value of “shame that cannot be shared,” namely that a shameful act committed by an individual will shame the members of the entire family. This is no longer the case because of the social changes that are taking place.

This revelation underscores the findings of previous researchers, who noted a shift in the Minangkabau kinship system due to economic factors and rantau (Mukhneri, 2017; Naim, 1971). The extended family system has been reconstructed and modified to function primarily as an identity and place where legitimization can be found. In economic affairs, nuclear families tend to act independently, as they no longer rely on traditional assets and heirlooms for their livelihoods.

Based on this explanation, it may be stated that a traditional element has been lost from the family lives of those women who have entered elderly care homes. The cohesion of the extended family has been eroded as traditional economic assets have become less important as a means of earning income and maintaining social bonds (Grischow, 2008; Sharifi & Murayama, 2013). Giddens (2010) noted that traditional practices can be lost when diverse interpretations of established practices and norms emerge. Furthermore, as modern society has been marked by the rejection of tradition as a form of legitimization, such rejection can potentially be a significant source of deroutinization. Changes are always integrated within the structuration process, regardless of how small they are.

The findings of this study show that material transformations result in social adaptations (Cohen, 2012). Referring to Harper and Leicht (2018), it may be said that the social shifts within a society stem from material changes. One factor that has destabilized the matrilineal system is the reduced degree of economic cooperation within households due to alternative financial resources and the erosion of communal/shared ownership (Edwin, 2006). This situation further reinforces the idea that material factors are one of the causes of the weakening of the social solidarity system in traditional societies (Misztal, 2003).

Conclusion

Shifts in the care patterns of elderly women in Minangkabau indicate complex interactions between the changing understanding of familial bonds, the emergence of a practical awareness of women as creative and interactive actors, and the development of elderly care homes as alternative care providers. Social transformations in Minangkabau society have led to the erosion of traditional elements, structures, and regulations (including communal assets) that have long served to maintain the cohesion of the extended family. Based on these types of material support, the traditional infrastructure has given way to a nuclear family model.

Cultural figures and traditional leaders have not readily accepted these changes in the objective condition of the Minangkabau people. As such, women leaving rumah gadang and entering elderly care homes (as a consequence of family spaces becoming less inclusive) have been viewed as opposing the communalist ideology that dictates how women should be treated in Minangkabau culture. Conservative members of Minangkabau society have continued to promote ideals of elderly care that do not reflect the current social reality of elderly community members.

Research on older adults cannot be separated from the cultural configuration and dynamics of the society in which children and parents interact. As such, when the elderly leave their family home because of social pressure or individual choices, their social bonds are severed. Traditional approaches are no longer used to maintain community cohesion, while globalization has marginalized tradition, leading to a major change in the Minangkabau code of conduct.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the older adults who participated in this study.

References

-

Abrams, D., & Hogg, M. A. (2001). Collective identity: Group membership and self-conception. In M. A. Hogg & R. S. Tindale (Eds.), Blackwell Handbook of Social Psychology: Group Processes (pp. 425–460). Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishers.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470998458.ch18]

-

Andel, R., Hyer, K., & Slack, A. (2007). Risk factors for nursing home placement in older adults with and without dementia. Journal of Aging and Health, 19(2), 213–228.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264307299359]

- Bappenas RI. (2020). Peraturan Presiden Republik Indonesia [Regulation of the President of the Republic of Indonesia]. In Demographic Research.

-

Blaakilde, A. L. (2001). Old age, cultural complexity, and narrative interpretation. In D. N. Weisstub, D.C. Thomasma, S. Gauthier, & G. F. Tomossy (Eds.), Aging: Culture, health, and social change (pp. 175–176). New York: Springer.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-0677-3_11]

- Blackwood, E. (2000). Webs of power: Women, kin, and community in a Sumatran village. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Publisher.

-

Blackwood, E. (2001). Representing women: The politics of Minangkabau Adat writings. The Journal of Asian Studies, 60(1), 125–149.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/2659507]

-

Buckinx, F., Allepaerts, S., Paquot, N., Reginster, J. Y., de Cock, C., Petermans, J., & Bruyère, O. (2017). Energy and nutrient content of food served and consumed by nursing home residents. Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging, 21(6), 727–732.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-016-0782-2]

-

Cohen, L. M. (2012). Adaptation and creativity in cultural context. Revista de Psicología, 30(1), 3–18.

[https://doi.org/10.18800/psico.201201.001]

- Dinas Kesehatan Provinsi Sumatera Barat. (2016). Renstra Dinas Kesehatan Provinsi Sumatera Barat 2016-2021 [West Sumatra Provincial Health Service Strategic Plan for 2016-2021].

- Edwin. (2006). Tanah Komunal: Memudarnya Solidaritas Sosial pada Masyarakat Minangkabau [Communal Land: Fading Social Solidarity in Minangkabau Society]. Padang, West Sumatra: Andalas University Press. https://onesearch.id/Record/IOS2779.slims-50070?widget=1

- Endrizal, E. (2006). Kerentanan Struktural Laki-Laki Lanjut Usia dalam Masyarakat Matrilineal Minangkabau [Structural Vulnerability of Older Men in Matrilineal Minangkabau Society]. Jurnal Informasi Kajian Permasalahan Sosial Dan Usaha Kesejahteraan Sosial, 11(3), 12–26.

-

Giang, L. T., Hong, T., Pham, T., Phi, P. M., Pham, T., & Phi, M. (2019). Productive activities of the older people in Vietnam. Social Science and Medicine, 229(1), 32–40.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.09.054]

- Giddens, A. (2010). Teori Strukturasi, Dasar-Dasar Pembentukan Struktur Sosial Dalam Masyarakat. Yogyakarta: Pustaka Pelajar.

-

Grischow, J. D. (2008). Rural “Community,” chiefs and social capital: The case of Southern Ghana. Journal of Agrarian Change, 8(1), 64–93.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0366.2007.00163.x]

- Hakimy, I. (1984). Rangkaian Mustika Adat Basandi Syarak di Minangkabau [Basandi Syarak Traditional Mustika Series in Minangkabau]. Bandung: Rosdakarya.

-

Hansen, E. B., & Gottschalk, G. (2006). What makes older people consider moving house and what makes them move? Housing, Theory and Society, 23(1), 34–54.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/14036090600587521]

-

Harper, C. L., & Leicht, K. T. (2018). Exploring social change. New York: Routledge.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315166421]

-

Hartati, N., Minza, W. M., & Yuniarti, K. W. (2021). How children of divorce interpret the matrilineal kinship support in changing society? : A phenomenology study from Minangkabau, West Sumatra, Indonesia. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 62(4), 276–294.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/10502556.2021.1871836]

- Huitt, W. (2004). Moral and character development. Valdosta, GA: Valdosta State University. Available at http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/topics/morchr/morchr.html

-

Ikhwan, I., Barlian, E., & Syah, N. (2023). Remote Sensing Based Modeling of Land Use Change on Ulayat Customary Land in Tilatang Kamang Sumatera Barat. TEM Journal, 12(3), 1559–1565.

[https://doi.org/10.18421/TEM123-37]

-

Leslie, W., & Hankey, C. (2015). Aging, nutritional status and health. Healthcare, 3(3), 648–658.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare3030648]

-

McLean, R. R., & Kiel, D. P. (2015). Developing consensus criteria for sarcopenia: An update. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 30(4), 588–592.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.2492]

-

Misztal, B. A. (2003). Durkheim on collective memory–Introduction: The Durkheimian tradition. Journal of Classical Sociology, 3(2), 123–143.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/1468795X030032002]

-

Mukhneri, M. (2017). Transmission of embedded skill in Minangkabau society: An analysis of best practice of Minangkabau migrants. Indonesian Journal of Educational Review, 4(1), 67–83.

[https://doi.org/10.21009/IJER.04.01.07]

-

Naim, M. (1971). Merantau: Causes and effects of Minangkabau voluntary migration. Singapore: Iseas Publishing.

[https://doi.org/10.1355/9789814380164]

-

Prastiwi Andar, D. (2020). Perilaku Kesehatan Pada Masa Pandemi Covid-19 [Health Behavior During the Covid-19 Pandemic]. Culture & Society: Journal of Anthropological Research, 1(1), 31–37.

[https://doi.org/10.24036/csjar.v2i2.59]

- Radjab, M. (1969). Sistem Kekerabatan di Minangkabau [Kinship System in Minangkabau]. Padang Panjang, West Sumatra: Center for Minangkabau Studies.

-

Rapaport, C., Lurie, T., Cohen, O., Lahadeg, M. L., & Limor Aharonson, D. (2018). The relationship between community type and community resilience. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 31, 470–477.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.05.020]

- Reenen, J. (1996). Central pillars of the house: Sisters, wives, and mothers in a rural community in Minangkabau West Sumatra. Netherlands: CNWS.

-

Saarnio, L., Boström, A. M., Hedman, R., Gustavsson, P., & Öhlén, J. (2017). Enabling at-homeness for residents living in a nursing home: Reflected experience of nursing home staff. Journal of Aging Studies, 43(October), 40–45.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2017.10.001]

-

Sharifi, A., & Murayama, A. (2013). Changes in the traditional urban form and the social sustainability of contemporary cities: A case study of Iranian cities. Habitat International, 38, 126–134.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2012.05.007]

-

Tegnan, H. (2015). Legal pluralism and land administration in west Sumatra: The implementation of the regulations of both local and Nagari governments on communal land tenure. Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law, 47(2), 312–323.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/07329113.2015.1072386]

- Wreksoatmodjo, B. R. (2013). Perbedaan Karakteristik Lanjut Usia yang Tinggal di Keluarga Dengan yang Tinggal di Panti di Jakarta Barat [Differences in the characteristics of elderly people who live in families and those who live in homes in West Jakarta]. Cermin Dunia Kedokteran 209, 40(10), 1–6.

Biographical Note: Alfan Miko has served in the Department of Sociology, Andalas University for 35 years. He is consistent in the realm of Sociology starting from undergraduate degree at Universitas Andalas Padang, master degree at Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta and doctoral degree at Universitas Padjadjaran in Bandung. His reseach interest includes development issues, socio-cultural changes and families studies, especially the elderly. This can be seen from his publications in the form of books or journal articles so far.

Biographical Note: Delmira Syafrini is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Sociology, Faculty of Social Science, Universitas Negeri Padang, West Sumatra, Indonesia. She is consistent in the realm of Sociology starting from undergraduate degree at Aniversitas Andalas Padang, master degree at Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta and doctoral degree at Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung. Her research interest includes the sociology of tourism, sociology of development and studies of socio-cultural change in society.

Biographical Note: Jendrius is a senior lecturer at Department of Sociology, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Andalas, Padang, West Sumatra, Indonesia. Jendrius completed his doctoral degree in The Gender Studies Program, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur Malaysia in 2015 and defence his dissertation entitled “Decentralization, Local Direct Elections and Return to The Nagari: Women’s Involvement and Leadership in West Sumatra”. Apart from teaching, Jendrius conducted several academic and research activities. He is interested in issues gender equality and justice in the family and politics as well as as well as issues of violence and masculinity.