Reaching Inner Motives: Learning from Self-Determined Women Tour Guides in Sri Lanka

University of Colombo, Sri Lanka University of Colombo, Sri LankaAbstract

The aim of the paper is to understand how women tour guides in Sri Lanka survive and what motivates them to thrive in the highly male-dominated travel and tourism industry in Sri Lanka. It employed a qualitative approach, using thematic analysis as its analytical strategy. The research identified, using Self-Determination Theory, how the survival of women tour guides is influenced by their motivations and the fulfillment of psychological needs that guide their work behaviors. Intrinsic aspirations were found to be the primary factors influencing their career choices. These tour guides strive to satisfy psychological needs such as autonomy and competence through various work behaviors. This study suggests the importance of societal awareness of the national tour guide occupation, reform the purposes of education in line with the travel and tourism industry requirements, and encourage government bodies to provide equal opportunities.

Keywords:

Women tour guides, Self-determination, Motives, Sri Lanka, Tourism industryIntroduction

The tourism industry has become a cornerstone of the global economy (Aynalem et al., 2016), contributing significantly to gross domestic product (GDP) and creating numerous job opportunities (World Travel and Tourism Council, 2022). Globally, the industry accounts for 1 in 11 jobs, with women comprising 54% of the workforce (World Travel and Tourism Council, 2022). In Asia and the Pacific regions, women make up 52% of tour guides (World Travel and Tourism Council Regional Report, 2022), while this rate is considerably low in some countries including Turkey (Alrawadieh & Alrawadieh, 2020), Jordan (Masaden et al., 2018), Sri Lanka (Mudalige, 2021), and Egypt (Mousa et al., 2023). Even though women employees constitute more in the tourism industry worldwide, gender inequalities of their participation are common. Women in the tourism industry face many challenges due to seasonality, job rotation, part time work and precarious contracts (Araújo-Vila, Otegui-Carles & Fraiz-Brea, 2021). These women are commonly placed on low paid and low skilled fields to that of males in the same (Nguyen; 2022).

The tourism sector remains crucial to Sri Lanka’s economy, contributing 6.1% of the national GDP and serving as a major source of employment and foreign exchange (World Travel and Tourism Council, 2022). Renowned for its adventure offerings, Sri Lanka has become a must-visit destination (McGraw, 2023). Regardless of the importance of tourism industry to the Sri Lankan context, female seems to be underrepresented in the Sri Lanka’s hotel industry and the affiliated field of tour guiding due to socio cultural barriers in country (Perera, Wasantha, Lakshan, & Bandara, 2024; Kodagoda & Jayawardana, 2022; Silva & Mendis, 2017). For example, out of 1425 licensed National Tour Guides (NTGs) in Sri Lanka, only 64 are women, representing approximately 6% of all registered NTGs, with just ten currently active (Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority, 2018).

Although women dominate the world tourism industry (World Travel and Tourism Council Regional Report, 2022), surprisingly the tour guide statistics in Sri Lanka show women are underrepresented whereas males dominate the tour guide job (Mudalige, 2021). Hence, it is questionable how just 6% of women NTGs survive and exist in the Sri Lankan context. Therefore, this study aims to explore how existing women NTGs in Sri Lanka navigate the challenges of a male-dominated industry and what strategies they employ for their survival. Section 2 discusses theoretical concepts related to women’s behavior in the travel and tourism industry. Drawing on Self-Determination Theory (SDT), we look into how women tour guides' intrinsic and extrinsic motivations blend with their three psychological needs of autonomy, competence and relatedness to decide their behavior in the tour guide occupation. Section 3 outlines the study’s methodology, while Section 4 presents insights from key respondents to address the research questions. Finally, Section 5 offers conclusions, discussion, and practical implications. This paper also contributes significantly to the literature by shedding light on the experiences and practices of women NTGs in Asia and specially for Sri Lanka, filling the gap of the empirical research on their motivations and coping strategies within a male-dominated industry in Sri Lanka. Accordingly, the paper broadens the geographical scope of existing literature and raises awareness of the socio-economic empowerment of women in developing nations. Finally, it provides practical recommendations for stakeholders in Sri Lanka’s tourism sector.

Literature Review

Traditionally, women’s roles in society were primarily confined to the domestic sphere, providing comfort to family members (Rimkute & Sugiharti, 2024; Schrems, 1987) and supporting their husbands’ occupations (Salmi & Sonck-Rautio, 2018). Many women were occupied in low-value occupations, extending their daily household responsibilities (Schrems, 1987). However, rapid labor force participation among women began during the mid-twentieth century alongside industrialization. Currently, approximately half of working-age women globally participate in the labor force, significantly contributing to economic development (Kim & Lee, 2024; World Bank, 2022). Along with the increased representation in the paid labor force, women face substantial employment challenges. The International Labor Organization (2015) reports that women’s opportunities in the labor market lag behind men’s, with a global gender gap in employment averaging 31.4% that needs narrowing (World Economic Forum, 2021).

There seems to be many gender-based inequalities in the tourism sector transforming this industry into a highly gendered industry (Jackman, 2022). According to UNWTO (n.d), women perform most of the unpaid work in family tourism businesses while they also concentrate in lowest paid and lowest status occupations in tourism (Kodagoda & Jayawardana, 2022). Women are supposed to be engaged in more care work in the industry which needs more of interpersonal skills but they are excluded from key managerial positions (Ramchurjee, & Paktin; 2011). The socio-cultural formation of women’s roles in society plays a significant role in setting up challenges for women tour guides. The long working hours and intensive job duties contradict the socially expected roles of women (Mousa et al., 2023; Masaden et al., 2018). The nature of the occupation, with its long and irregular working hours, has caused women tour guides to experience sexual harassment, leading to lower job satisfaction, decreased psychological well-being, and, ultimately, burnout (Mousa et al., 2023; Alrawadieh & Alrawadieh, 2020). Religious beliefs in society also influence women’s career behavior in the travel and tourism industry (Koburtay et al., 2020). Mobility restrictions imposed on some women have become a significant challenge (Al-Asfour et al., 2017).

Along with these challenges, women are increasingly taking up tour guide positions. Tourism related occupations have fostered economic growth by reducing poverty and gender inequalities (Scheyvens, & Hughes, 2021). In addition, women have become integral to the travel and tourism industry (World Travel and Tourism Council, 2022). ‘Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls’ has become one of the main 2030 agenda for sustainable development (United Nations, n.d) and this has shed light on sustainable tourism practices too (Pu, Cheng, Samarathunga, & Wall, 2023). A survey showed a growing number of women entering the tour guide occupation. The results highlighted senior women tour guides acting as role models for newcomers, encouraging them to deviate from traditional gender understandings of women in society (Issuu, 2023). Research has acknowledged that women strategize their femaleness to prosper and survive in tourism as tour guides (Vandegrift, 2008).

Studies on the success stories of women tour guides highlight that they use self-inspiration and self-determination to survive and thrive. This is evident in how East African women in the territories of Rwanda, Kenya, Tanzania, Burundi, and South Sudan seized job opportunities when they arose, receiving the necessary training, skills, support, and mentorship (Mutesi, 2022). Another compelling example is the first woman tour guide in Afghanistan, who succeeded in making her dream job a reality (Euronews.travel, 2022). She explained how she used strategies to change her career by being a refugee instead of a victim of society. Her story reveals how she effectively used self-determination to achieve personal development and fulfill her inner motives. Despite the male-dominated nature of the tour guiding occupation, women tour guides are reported to have unique gendered experiences that contribute to their well-being (Alrawadieh & Alrawadieh, 2020; Cheung et al., 2018). For instance, various adventure-related activities have been shown to enhance women’s well-being and meet their basic psychological needs (Lloyd & Little, 2010). Hall’s (2018) research findings revealed that self-esteem, confidence, and a sense of accomplishment were enhanced among women in tour guide jobs.

Number of studies used Self Determination Theory (SDT) to explain how individual differences, such as aspirations or goals, are mediated by motivation and the fulfillment of psychological needs to determine work behaviors and well-being (Deci et al., 2017; Mackenzie et al., 2020). According to Deci et al. (2017), people can have several intrinsic aspirations, such as community contributions (generativity), personal development, meaningful relationships, physical fitness, and extrinsic aspirations. These aspirations shape an individual’s motivation and satisfaction with basic psychological needs. An individual’s autonomous motivation, central to SDT, involves engagement with willingness, volition, and choice, leading to intrinsic motivation for high-quality performance and wellness (Deci et al., 2017). Accordingly, autonomous motivation is supported by an individual’s understanding of the purpose and worth of their jobs, feeling ownership and autonomy in carrying them out, and receiving clear feedback and support. When autonomous motivation drives a person, that person is likely to be autonomous and self-directed (Ryan & Deci, 2008). SDT suggests that intrinsic motivation assists in meeting the individual’s three fundamental psychological needs for human flourishing: Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness (Deci & Ryan, 2008). According to their explanations, autonomy is an individual’s feeling of control over their own life and choices, competence is their feeling of capability and effectiveness in their actions, and relatedness is their feeling of connection and care from others in society (Deci & Ryan, 2008).

Self-determination theory is used as a theoretical framework to understand many aspects in tourism field; motivation, wellbeing, experiences, satisfaction, employment aspiration, behavioural intentions (Ciki, Kizanlikli, Tanriverdi, 2024, Hsu, 2013; Buzinde, 2020). It has found out that autonomy, competence and relatedness decide the experiences of tourists (Scannell & Gifford, 2017). Ciki, Kizanlikli , Tanriverdi (2024) identified the need for autonomy as tourists desire to explore new destinations, their need for competence is reflected in learning of new culture or skill while relatedness is interaction with others including locals. Tour guides have the responsibility to develop their knowledge, intercultural communication skills and personality to give positive impressions for tourists (Sari & Yüzbaşioğlu, 2024). Competency of tour guides have identified important in deciding satisfaction and revisit intention of tourists (Kul, Dedeoğlu, Küçükergin, De Martino, & Okumus; 2024; Harara, Al Najdawi, Rababah, & Haniyi, 2024). Studies have found out female tourist frontliners have highest English language competence compared to males (Tubang-Delgado, 2024). In addition to the competence, tour guides try to maintain sustainable tourism practices through harmonious host–guest relationships integrating their knowledge and experiences (Pu, Cheng, Samarathunga, & Wall, 2023).

Women’s determination has been identified as a main driving force in choosing their occupation as tour guides in the travel sector (Tourism Tiger, n.d.). Mackenzie et al. (2020), in their study using Self-Determination Theory (SDT), identified how women tour guides behave and how they form self-determination to enhance their performance and psychological well-being. These women tour guides’ narrations reveal how their perceptions are linked to their basic psychological needs, and enhance or hinder their well-being. Furthermore, the research identified women adventure tour guides’ proactively created strategies to meet basic psychological needs to enhance their well-being. As there is a lack of understanding of women tour guides in Sri Lanka, it is interesting to find out using dimensions in SDT how women tour guides in Sri Lanka motivate themselves and what strategies existing women NTGs use for survival.

Methods

Qualitative approach has been taken to obtain in-depth insights from women tour guides to understand how the existing women NTGs survive and what strategies they use in a highly male-dominated industry (Kodagoda, 2013). The study sample consisted of seven NTGs who are currently active as tour guides in Sri Lanka. Finding NTGs was a challenging task for the researcher because only ten women NTGs are active, although the registered NTG number is 64. Therefore, the snowball sampling method used to reach the required number of samples (Kodagoda, 2022). These women tour guides have obtained the license from Sri Lanka Institute of Tourism and Hotel Management to work as National Tour guides in Sri Lanka. However, currently all the women NTGs in the sample work independently without attaching to any hotel, agency or an institute in Sri Lanka (Please see Table 1 below’). They tend to find their customers with the help of the customer relationships they maintain and the network they have built with the other tour guides (women or men) in Sri Lanka. Since all the women tour guides are self-employed, it was not practical or possible to obtain any institutional approval, but throughout, researchers were very keen on ethical considerations of human, especially women participation. We have adhered to the American Psychological Association’s (APA) Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct to protect the human subjects involved in the research (American Psychological Association, 2017). We have also used several methods to guarantee the confidentiality and anonymity of the results being reported.

Access to these women NTGs was gained by arranging appointments over the phone. All the women NTGs provided a convenient time slot for the interviews just after they had completed their tours. This arrangement made the NTGs feel relaxed and comfortable, allowing them to spend quality time in the interviews. The interviews with all participants began with some warm-up questions and asked about a series of structured questions: age, civil status, educational level, and number of years work as a tour guide. The interview guide mainly covered open-ended questions. Participants were asked to describe how they feel about their job, who inspired them to be in this profession and how they rely on their ways to continue the job. Some questions were changed as to the participant’s responses to the interview questions. Once the interviews were completed, their real names were removed, and collected information was transcribed and at the coding process themes were identified. Data transcribing was done in a private room using earphones to keep all the information in interviews confidential. Research findings were discussed using pseudo-names to ensure the confidentiality and anonymity of the data obtained during the interviews. Data saturation was reached when seven women tour guides were interviewed, and no new themes were generated after that point.

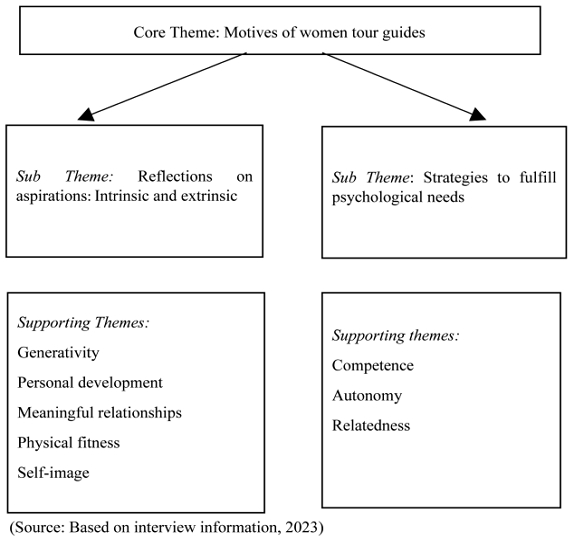

The data was analyzed manually using the thematic analysis method. We followed the five stages as suggested by Braun and Clarke (2006). Those stages are; familiarization with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, refining the themes, defining and naming themes and finally finding appropriate labels which convey the essence of the theme. We identified this analysis method as a convenient and flexible method for this study. To become familiar with the transcribed datasets (Mason, 2002), all the interview information was read a number of times. In addition, the analysis involved careful reading the textual data, for example field notes. Similar statements were highlighted to identify the key information of participants’ accounts. Among different patterns of data sets, emerging themes were chosen to address the research problem identified. Finally, the two main themes identified were framed around the women in the tour guides occupation. Finally, the two main themes identified were framed around the women in the tour guides occupation. Participants discussed mainly the dimensions of the SDT using their own words. For example, a female tour guide in the sample explained how the beauty of the land motivated her to become a tour guide through intrinsic and extrinsic motivations to get job satisfaction and wellbeing. This was themed as reflections on aspirations of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations. In addition, participants highlighted the different strategies to achieve their basic psychological needs, autonomy, competence and relatedness to strengthen their presence in the industry (Deci & Ryan, 2008; Cıkı & Tanrıverdi, 2023). Thus, we named this theme as strategies to fulfill psychological needs. Accordingly, the two main themes derived are reflections on aspirations and strategies to fulfill psychological needs (Please see Figure 1 below).

Findings

This section explains the results obtained from the interviews with women NTGs. Research findings are categorized under two main themes: reflections on aspirations, strategies to fulfill psychological needs. Firstly, the intrinsic aspirations section elaborates on the women tour guides’ desire for their occupation and what drives their life goals. Secondly, the unique strategies used to achieve psychological needs are discussed. Two key themes stem from the inner motives of women tour guides to select the tour guide occupation as their career. These inner motives form the self-determination to become a tour guide, making it the core theme of the study.

Reflections on Aspirations: Intrinsic and Extrinsic

All the women NTGs interviewed expressed a strong desire to select their current occupation as tour guides. This desire was evident at the beginning of their career choice and was one of the reasons for their enthusiastic engagement in their careers. These aspirations are intrinsically driven by the women tour guides themselves, while extrinsic aspirations also play a role. Firstly, the intrinsic aspirations or life goals of NTGs are mainly associated with their desire for generativity and personal development. Their willingness to contribute to the community reflects their generativity, while their development that supports occupational performance is identified as personal development (Deci et al., 2017). Meaningful relationships and physical fitness are also connected to their occupational roles, forming their intrinsic aspirations. Additionally, some women tour guides expressed how their extrinsic aspirations, such as an attractive image, persuaded them to become self-determined tour guides in the field.

Generativity

Accompanied by the strong desire of women tour guides to take up their occupation, their choice is linked to a strong bond with their native land, Sri Lanka. These women tour guides expressed how they are mesmerized by the beauty and ample natural resources available in the country. NTG 04 shared how the beauty of this land motivated her to become a tour guide. Her narration reveals how she sees Sri Lanka as naturally blessed. Further, her roots in becoming a tour guide were linked to fulfilling her psychological need for generativity. She expressed her motivation for promoting the country’s beauty and traditional medicine and healing methods. She explained her view:

I had a crazy feeling towards this country. This is a resourceful country, and we could do a lot for this country. There are no seasonal changes if a country is closer to the equator. More than 50% of this land is hidden because the archaeological sites are still unexplored. Many traditional healing methods exist, but no market is open for them. We can create a good market if we focus on medical tourism.

NTG 03 revealed a similar idea about the country and its nature. Her inner feelings reflected how she values and admires the nature of Sri Lanka as a woman tour guide. It was observed that she was serious when she shared her thoughts about her performance in this role. She stated that she is committed to her occupation and takes on all kinds of tours without being as selective as some other women tour guides. This reflects her need for generativity, as she wants to deliver maximum value to the tourists regardless of the complexity of the tour.

Everyone cannot do this job. There should be a concern about the country and the environment. This job is not as easy as a job we do in the office environment. Some people don't like to be exposed to the sunlight. Some people skip adventures. You cannot give up. I manage to do all kinds of tours, ranging from simple one-day expeditions to adventure guides in forests.

Personal Development

The life goals of these women tour guides have compelled them to establish their backgrounds as an ideal fit for their dream jobs. They have completed several educational qualifications and mastered one or more foreign languages. Many have invested considerable effort in mastering their preferred languages and obtaining relevant educational qualifications. This dedication reveals how these women tour guides exert effort for their career development in their chosen field. NTG 01 shared her interest in studying the language she preferred.

My brother wanted me to study German since he is a guide who mastered the German language. But my interest was in the Japanese language, so I did it. I had to go to Japan on several occasions to learn the language.

NTG 05 revealed how she was determined to be the best fit for her desired job and how her passion for learning made her a strong character in tourism. Her narration highlights her wide range of expertise and career development as follows:

I have completed a Bachelor of Arts degree. Tourism and travel management is included in that course. I have a postgraduate diploma in airline ticketing. In addition, I have completed Japanese language tests up to level 04. Even though I have got a scholarship to Japan, I decided to select India for my further studies. I have studied Archeology. I get a holiday after every tour and get used to doing something new in each session. Being a tour executive with a small salary, I reached the position of tour director, which is the highest-level position.

Meaningful Relationships

As the women tour guides provide direct and frontline service to their clients, they can create meaningful relationships. The ability of these tour guides to form such relationships intrinsically motivates them to perform their job roles. NTG 01 explained how she developed a long-lasting relationship with a Dutch family. She revealed how she helped recover two drug-abusing daughters in this family through her in-depth teachings about Buddhism and the cultural values of Sri Lanka. She further explained how she enjoyed the lifelong satisfaction of rescuing two valuable lives because of her intervention as a woman tour guide. She described the relationship she built with that family:

The parents thanked me a lot for the help I gave for their two daughters to overcome their drug-abuse behavior. They were surprised by my service because they have attempted several times to change their behavior, which unfortunately failed all the times. They gave me valuable presents before leaving the country, and, even today, they invite me to visit them.

When tour guides provide exceptional service to their clients, those clients often return to their countries and recommend the local tour guide to their friends. Many women tour guides receive such recommended tours due to the meaningful relationships they cultivate with their clients through their service delivery. This opportunity not only brings satisfaction but also intrinsically motivates them to continue their occupation. NTG 07 explained how she thrives in this industry because of the meaningful relationships she maintains, as follows:

Most of the time, my clients recommend me, give good reviews to their friends, and have a tour with me in Sri Lanka. As my name is specifically mentioned to the tour guide agency here, they can’t omit their request.

Physical Fitness

The active nature of tour guides enables them to provide exceptional service to their clients. Being capable of supporting needy clients and staying active during the tour are identified as primary personal characteristics that are essential for fulfilling the tour guide’s occupational role. NTG 06 explained the physical fitness requirements of a tour guide as follows:

We should be alert to needy people and stretch our helping hand whenever they need our assistance. For example, getting off the bus may be difficult for older people. That is the level of courtesy we must build up when doing this occupation.

In addition to their intrinsic aspirations, extrinsic aspirations for an attractive image have influenced these women tour guides in choosing their occupation. NTG 06 explained how the idea of being a tour guide has been on her mind since childhood. Her thoughts reflected her admiration for the image of a tour guide, as follows:

My brother is a tourist guide, mastering the German language. Our family had a strong background in tourism. When foreigners used to visit our homes frequently, I had a strong desire to be a tour guide one day.

NTG 02 also revealed, with a strong attitude, how her long-lasting desire to be a tour guide paved the way towards a reality. She enthusiastically revealed her pride in having an occupation with an attractive image. Her current attitude about the occupation is as follows;

This is my dream career. I always wanted to be a tour guide. So, I am now. I was the youngest woman tour guide in this field when I was selected. This is my first job, and I don’t think I will change it for any reason.

Strategies to Fulfill Psychological Needs

Currently active women tour guides in Sri Lanka demonstrate a strong passion for their chosen field. Their aspiration to become NTGs in Sri Lanka is driven by intrinsic goals such as generativity, personal development, meaningful relationships, and physical fitness. Generativity and personal development are particularly significant intrinsic aspirations for these women tour guides. Additionally, it is evident that extrinsic aspirations also contribute to their strong desire for their chosen occupation. Fulfilling their lifelong career ambitions satisfies their basic psychological needs. The presence of extrinsic aspirations, intrinsic motivations primarily propel them towards autonomous motivation. This autonomous motivation, identified as intrinsic motivation, empowers these women tour guides to fulfill their basic psychological needs.

While these women tour guides are intrinsically motivated by their aspirations, the study has identified that they employ various strategies to fulfill their basic psychological needs. Deci & Ryan (2008) posit that autonomy and competence are fundamental psychological needs for individuals. These NTGs employ diverse strategies to satisfy these basic psychological needs and achieve their life goals. Instead of being preoccupied with barriers or societal stereotypes, these women tour guides have developed these basic psychological needs as strategies to strengthen their presence in the industry. These innovative approaches have created numerous opportunities for them in their field, leading to greater job satisfaction and wellbeing (Deci & Ryan, 2008; Cıkı & Tanrıverdi, 2023).

Competence

NTG 03's narrations revealed how she has developed her own approach to the tour guide occupation. By effectively delivering her services in her unique way, she has gained a sense of capability and effectiveness in her role. She explained how she achieved competence as a woman tour guide through her strategies, as follows:

I used to keep a diary to get feedback during each of my tours. Even today, the comments I have received from my clients bring tears to my eyes. If someone asks about my experience, I don't talk much. I show the diaries I have maintained.

Additionally, NTG 03 has shared how she developed competence in her role and effectively caters to her clients. Her narration highlights her capability in delivering services to a diverse range of clients, as follows:

People have different capacities to understand things. I have developed my presentation skills to cater to the clients. People also have differences in their interests and tastes, so they question us from multiple angles. We need to handle all those clients without making them dissatisfied.

NTG01's story exemplifies her proficiency in the chosen field, having been selected to cater to an affluent group of tourists in Japan. Her skills in service delivery were recognized by Japanese representatives, resulting in her being chosen as the sole woman tour guide among the group serving affluent Japanese tourists. She describes her experience with pride in her voice, stating:

Once, our company got a chance to cater to 275 tourists, including famous singers and actresses in Japan. There were some buses and tour guides to cater to that group. Japanese representatives who came to Sri Lanka to assess the suitability of tour guides were impressed when I performed, and I was selected for the VIP bus. The VIP bus contained the affluent, including famous actors, singers, and dancers from Japan. I was the only woman guide selected for this tour.

Autonomy

In addition to achieving competence in the tour guide occupation, these women tour guides have also found autonomy through self-determined strategies. NTG 01 revealed her desire to take control of her career, despite prevailing societal stereotypes. Her story illustrates how she made her career choice and achieved autonomy, as follows:

Even though I wanted to become a tour guide, I was limited by my family. We were not allowed to leave home until we got married. So, I shrank all my desires until I got married. However, I started doing my dream job after getting married and having kids.

Women tour guides tend to carry out their jobs in a principled manner, adhering to a set of principles that encourage them to excel in their roles. Working according to principles has helped them achieve autonomy in their field. NTG 05 shared her thoughts on how her principles have benefited her career. By adhering to a principle of working exclusively with leading companies, she has established autonomy in her job role.

I have worked with the top companies in Sri Lanka and have never met any difficulty because of that. I have been to many 5-star hotels with good facilities. I have handled many luxury tours in my life. I don't accept a tour if I am not provided accommodation. I think about my safety. I have never experienced someone knocking on my room door in a hotel room.

NTG 01 also explained how she has formed autonomy over her career and what will happen if someone fails to create control over her career. Her narration reveals how she strategizes to gain control over her career;

Foreigners usually question the role of women in society. They question whether we smoke or drink. Then I said no to all these questions. If my answer is no, then the reality should also be no. When we stay according to our policy, they will respect us.

Further, she revealed the consequences of not behaving in a well-mannered way. According to her views, if women over utilize the freedom they have, there were many incidents where women guides ruined their whole careers.

There are new women tour guides who have just graduated from university. They are not aware of the field. You can earn well. And freedom, too. If you do not utilize freedom properly, there is no survival in this field.

NTG 07 added her thoughts as to how self-discipline helps to enhance the satisfaction of doing the job, although there are societal stereotypes;

In any field, if the person behaves well, no matter what others say about you. Suppose I know what I am doing.

While women tour guides effectively utilize autonomy and competence as self-determined strategies, there is little evidence about how they fulfill their relatedness needs. Nevertheless, these women tour guides have expressed a strong desire to connect with society. Their sentiments reflect a keen eagerness to gain societal acceptance, which they believe is essential for fulfilling one of the fundamental psychological needs for human flourishing: relatedness.

Relatedness

Despite achieving their autonomy and competence needs through their strategies, women tour guides strongly desire acceptance and belonging within their society. They advocate for correcting negative stereotypes associated with the occupation of National Tour Guide in Sri Lanka. NTG 05 expressed concern over how this profession is perceived as marginalized rather than valued by society. She emphasized the importance of raising awareness about this national occupation and promoting social acceptance for women succeeding in this field. As she explained:

Many women work for airlines, comparatively not in this field. That is because people are not aware of this. Again, it is their unawareness that this field is not that good. I am not a person from a Colombo school. Initially, I could not speak English properly, but I am doing well now. Women should be allowed to travel so that they can explore the world.

NTG 02 expressed concern over society’s lack of awareness regarding their occupation and the role they fulfill. She highlighted this as a significant barrier for women tour guides, emphasizing the importance of correcting societal perceptions. Her words underscored the urgency to elevate the social status of their occupation to fulfill their need for relatedness.

I think the first barrier for women tour guides comes from “unawareness.” Even though my family has a tourism background, they refused to let me do this job. So, one without a strong tourism background will never accept this as a valued job.

Key insights from the interviews are basically identified under two main themes; Reflections on aspirations and strategies to fulfill psychological needs. First theme, reflections on aspirations identified as the strong desire of interviewees to work as tour guides. Strong desire is again identified as intrinsic aspirations and extrinsic aspirations. Intrinsic aspiration of women tour guides are identified mainly in the forms of generativity, personal development, meaningful relationships and physical fitness. Generativity explains women tour guides willingness to contribute to the community. They mainly explain how their greater bond with the native land turned them to be as tour guides. Personal development reveals how these women tour guides developed their knowledge and other skills to better perform their chosen occupation. Hence, completion of educational qualifications or learning new foreign languages come under this category. Meaningful relationships explain how they value the long lasting and strong relationships they keep with their clients. Lastly the physical fitness explains how the active nature of women tour guides make it easy to perform the tour guide occupation. In addition to the intrinsic aspirations, the extrinsic aspiration of tour guides has motivated these women to be in the occupation. Both the intrinsic and extrinsic aspirations have flourished the motivation of these tour guides. In addition to intrinsic and extrinsic aspirations of women tour guides, they use strategies to fulfill their main psychological needs of autonomy, competence and relatedness. Autonomy of women tour guides explain how they use strategies to continue and thrive their career. Competence explained how they developed their own approaches to be in the tour guide occupation. Relatedness showed how women tour guides willingly to be connected to society. Finally, this study identified how these women tour guides have developed basic psychological needs as strategies to strengthen their presence in the male dominated industry.

Discussion

In this section, we explain how we used Self-Determination Theory as a theoretical lens to explore how women NTGs’ self-determination is driven by their intrinsic and extrinsic aspirations, their fulfillment of psychological needs (Autonomy, Competence, Relatedness), and the diverse behavioral strategies they employ to thrive in the industry. Firstly, women NTGs exhibit strong intrinsic aspirations related to generativity, personal development, meaningful relationships, and physical fitness. These aspirations fuel their pursuit of becoming tour guides. This aligns with previous research findings and parallels the journeys of women tour guides, such as those in Afghanistan, who overcome barriers to achieve their dreams (Euronews. travel, 2022). Senior women tour guides also play a transformative role in challenging traditional gender roles within their communities (Issuu, 2023). Establishing meaningful client relationships is another key strategy these women employ, leveraging their femininity to deliver exceptional service and maintain long-term connections (Vandegrift, 2008). Furthermore, alongside intrinsic and extrinsic aspirations, these women NTGs employ strategies to fulfill their psychological needs, particularly autonomy and competence, using self-determined methods. Tour guides competence has become a main determinant in tourists satisfaction and intentions to visit again (Kul, Dedeoğlu, Küçükergin, De Martino, & Okumus, 2024; Harara, Al Najdawi, Rababah, & Haniyi, 2024). Research studies have also found out the harmonious host guest relationships and English language competency developed by tour guides (Tubang-Delgado, 2024; Pu, Cheng, Samarathunga, & Wall, 2023). Gendered interactions also play a crucial role in supporting their fulfillment of psychological needs in a male-dominated industry, as highlighted by Mackenzie et al. (2020). Lastly, an intriguing finding is these women NTGs’ desire to fulfill their need for relatedness by raising awareness of their occupation, which is classified as a national-level occupation. Ciki, Kizanlikli & Tanriverdi (2024) has identified the concept relatedness in tourism as one’s willingness to connect with others. Their strong inner drive reflects their endeavor to gain societal recognition for their valued occupation. However, there is a lack of literature addressing women tour guides’ need for relatedness, indicating a potential area for future research.

Practical Implications

This study emphasizes several practical implications for policymakers to consider when making decisions. Firstly, there is a need to raise awareness about tourism-related national occupations across various educational levels and through mass media. Educating the public about the nature of these job roles and their benefits can help shift societal attitudes and encourage more individuals to consider careers in this field, thus breaking stereotypes. Secondly, reforms in the Sri Lankan education system are necessary to instill in children a deeper appreciation for their country’s environment and cultural heritage. This includes fostering attitudes of love and respect towards their motherland, which is rich in natural beauty and cultural significance. Additionally, teaching multiple foreign languages that are economically valuable to Sri Lanka should be prioritized. Finally, the Sri Lanka Tourist Board, as the primary governing body of tourism in the country, should enhance opportunities for women to enter the national tour guide occupation. It is crucial for this institution to provide supportive and respectful environments for women seeking to join this industry.

Conclusions

Despite the travel and tourism industry’s importance to Sri Lankan society, there are few active women tour guides as NTGs. This study aims to understand how these women navigate and survive in a predominantly male-dominated occupational category in Sri Lanka, exploring their strategies for industry resilience. The findings are interpreted through the lens of Self-Determination Theory (SDT) to comprehend the motivations driving these women tour guides to thrive in their profession. The study reveals that strong intrinsic and extrinsic aspirations intrinsically motivate these women tour guides and enable them to meet their basic psychological needs. Among the intrinsic aspirations of women NTGs in Sri Lanka, the desire for generativity and personal development prominently influences their career choices. Additionally, aspirations for creating meaningful relationships, maintaining physical fitness, and projecting an attractive image through their occupational role are identified as significant. Furthermore, the study highlights how these women tour guides employ self-derived strategies to fulfill their psychological needs. The implications of these findings suggest practical measures for Sri Lankan policymakers.

Limitations

Regardless of the scarcity of currently active women tour guides in Sri Lankan society available for selection, future research could benefit from employing triangulation or extensive research methods. Based on the findings of this study, future research could examine specific career barriers that women tour guides encounter, which could provide valuable insights for practitioners. Finally, additional exploration and research are warranted into the relatedness needs of women tour guides, as there is currently a paucity of studies focusing on this aspect.

References

-

Al-Asfour, A., Tlaiss, H. A., Khan, S. A., & Rajasekar, J. (2017). Saudi women's work challenges and barriers to career advancement. Career Development International, 22(2), 184–199.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-11-2016-0200]

-

Alrawadıeh, Z., & Alrawadıeh, D. D. (2020). Sexual Harassment & Wellbeing in Tourism Workplaces: The Perspectives of Female Tour Guides. In Vizacaino, Jeffrey & Eger (Ed.), Tourism and gender-based violence: challenging inequalities (pp. 80–92). Wallingford UK: CABI.

[https://doi.org/10.1079/9781789243215.0080]

- American Psychological Association. (2017). Ethical Principles of psychologists and code of conduct. Washington, USA

-

Araújo-Vila, N., Otegui-Carles, A., & Fraiz-Brea, J. A. (2021). Seeking gender equality in the tourism sector: A systematic bibliometric review. Knowledge, 1(1), 12–24.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/knowledge1010003]

-

Aynalem, S., Birhanu, K., & Tesefay, S. (2016). Employment opportunities and challenges in tourism and hospitality sectors. Journal of Tourism & Hospitality, 5(6), 1–5.

[https://doi.org/10.4172/2167-0269.1000257]

-

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research In Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

[https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa]

-

Buzinde, C. N. (2020). Theoretical linkages between well-being and tourism: The case of self-determination theory and spiritual tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 83, 102920.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102920]

-

Cheung, C., Baum, T., & Hsueh, A. (2018). Workplace sexual harassment: exploring the experience of tour leaders in an Asian context. Current Issues in Tourism, 468–1485.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1281235]

-

Çıkı, K. D., & Tanrıverdi, H. (2023). Self-determination theory in the field of tourism: A bibliometric analysis. Tourism: An International Interdisciplinary Journal, 71(4), 769–781.

[https://doi.org/10.37741/t.71.4.8]

-

Ciki, K. D., Kizanlikli, M. M., & Tanriverdi, H. (2024). Antecedents of cave visitors’ revisit intentions in the context of self-determination theory: a case study on dupnisa cave visitors in Turkey. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–6.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2024.2337280]

-

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self-determination theory: A macro theory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian Psychology, 49(03), 182–185.

[https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012801]

-

Deci, E. L., Olafsen, A. H., & Ryan, R. M. (2017). Self-determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behaviour, 4(01), 19–43.

[https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032516-113108]

-

Deci, E.L., & Ryan, R.M. (2000). The "what" and "why" of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(04), 227–268.

[https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01]

-

Dönmez, F.G., Gürlek, M. and Karatepe, O.M. (2024), Does work-family conflict mediate the effect of psychological resilience on tour guides’ happiness?, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 36(09), 2932–2954.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-01-2023-0077]

- Euronews.travel. (2022). A Changer, not a victim, meet Afghanistan's first female tour guide. Retrieved March 03, 2024, from https://www.euronews.com/travel/2022/03/08/a-changer-not-a-victim-meet-afghanistan-s-first-female-tour-guide

- Hall, J. (2018). Affective Geographies of Transformation, Exploration and Adventure. London: Routledge.

-

Harara, N. M., Al Najdawi, B. M., Rababah, M. A., & Haniyi, A. A. (2024). Jordanian tour guides' communication competency. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 15(3), 873–883.

[https://doi.org/10.17507/jltr.1503.20]

-

Hsu, L. (2013). Work motivation, job burnout, and employment aspiration in hospitality and tourism students—An exploration using the self-determination theory. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 13, 180–189.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2013.10.001]

- International Labour Organization. (2015, January). Women in Business and Management: Gaining Momentum. ILO. Retrieved June 21, 2024, from https://www.ilo.org/publications/women-business-and-management-gaining-momentum

- Issuu. (2023). Women who explore-the rise of female tour guides. Retrieved June 21, 2024, from https://issuu.com/liamfarnes0/docs/women_who_explore-the_rise_of_female_tour_guides, .

-

Jackman, M. (2022). The effect of tourism on gender equality in the labour market: Help or hindrance. Women's Studies International Forum, 90.102554. Pergamon.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2021.102554]

-

Kim, C. & Lee, S. (2024). From descriptive to substantive representation of women in times of crisis-. The case of Latin American countries. Asian Women, 40(3),1–25.

[https://doi.org/10.14431/aw.2024.9.40.3.1]

-

Koburtay, T., Syed, J., & Haloub, R. (2020). Implications of religion, culture, and legislation for gender equality at work: Qualitative insights from Jordan. Journal of Business Ethics, 164(03), 421–436.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-4036-6]

-

Kodagoda, T. (2013). Social issues and workplace culture: a case study in Sri Lanka. International Journal of Management and Enterprise Development, 12(3), 237–250.

[https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMED.2013.054518]

- Kodagoda, T. (2022). Hope and resilience as a management strategy to continue women in small business: experiences from Japan and Sri Lanka. Meiji Business Review, 69(01),73–92.

-

Kodagoda, T., & Jayawardhana, S. (2022). Forced or voluntary reluctance or voluntary preference to work. Women in hotel industry: evidence from Sri Lanka. Gender in Management: An International Journal,37(04), 524–534.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-01-2021-0011]

-

Kul, E., Dedeoğlu, B. B., Küçükergin, F. N., De Martino, M., & Okumus, F. (2024). The role of tour guide competency in the cultural tour experience: the case of cappadocia. International Hospitality Review. (Ahead of print)

[https://doi.org/10.1108/IHR-04-2023-0021]

-

Lloyd, K., & Little, D. E. (2010). Self-determination theory as a framework for understanding women's psychological well-being outcomes from leisure-time physical activity. Leisure Sciences, 32(4), 369–385.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2010.488603]

-

Mackenzie, S. H., Boudreau, P., & Raymond, E. (2020). Women's adventure tour guiding experiences: Implications for well-being. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 45, 410–418.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.09.006]

- Masadeh, M., Al-Ababneh, M., Al-Sabi, S., & Allah, M. H. (2018). Female tourist guides in Jordan: Why so few. European Journal of Social Sciences, 56(02), 89–102.

- Mason, J. (2002). Qualitative Researching. Sage.

- McGraw, J. L. (2023). Sri lanka is asia's best kept secret for unforgettable adventures. Retrieved June 21, 2024, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/jordilippemcgraw/2023/06/29/sri-lanka-is-asias-best-kept-secret-for-unforgettable-adventures/?sh=3e8004a24a11

-

Mousa, M., Abdelgaffar, H., Salem, I. E., Elbaz, A. M., & Chaouali, W. (2023). Religious, contextual and media influence: determinants of the representation of female tour guides in travel agencies. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 35(09),1–21.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-05-2022-0650]

- Mudalige, T. A. K. (2021). Identifying the triggering factors for female career choice: The case of tour guide in Sri Lanka. Journal of Business Administration and Languages, 9(1), 72–86.

- Mutessi, C. (2022). What it means to be an african female tour guide. ic4wb. Retrieved June 21, 2024, from https://ic4wb.com/what-it-means-to-be-an-african-female-tour-guide/

-

Nguyen, C. P. (2022). Tourism and gender (in) equality: global evidence. Tourism Management Perspectives, 41(06), 100933.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100933]

-

Perera, P. K. U., Wasantha, H. L. N., Lakshan, P. L. K., & Bandara, W. M. A. H. (2024). Barriers to female participation in Sri Lanka's hotel industry: A qualitative exploration of cultural, social, and organizational challenges. International Journal on Recent Trends in Business and Tourism, 8(4), 12–23.

[https://doi.org/10.31674/ijrtbt.2024.v08i04.002]

-

Pu, P., Cheng, L., Samarathunga, W. and Wall, G. (2023), Tour guides’ sustainable tourism practices in host-guest interactions: when Tibet meets the west, Tourism Review, 78(03), 808–833.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-04-2022-0182]

- Ramchurjee, N., & Paktin, W. (2011). “Tourism” a vehicle for women’s empowerment: prospect and challenges. University of Mysore: Manasagangotri, India.

-

Ren, L., Wong, C. U. I., Ma, C., & Feng, Y. (2024). Changing roles of tour guides: From “agent to serve” to “agent of change”. Tourist Studies, 24(1), 55–74.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/14687976231200909]

-

Rimkute, A. & Sugiharti, L. (2024). The Effect of Household Modernization on Married Women’s Empowerment in Indonesia. Asian Women. 40(4), 79–106.

[https://doi.org/10.14431/aw.2024.12.40.4.79]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2008). Handbook of personality: theory and research, New York: The Guilford Press.

-

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2024). Self-determination theory. In Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research. 6229-6235. Cham: Springer International Publishing

[https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-17299-1_2630]

-

Salmi, P., & Sonck-Rautio, K. (2018). Invisible work, ignored knowledge. Changing gender roles, division of labour, and household strategies in Finnish small-scale fisheries. Maritime Studies, 17(02), 213–221.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s40152-018-0104-x]

-

Sari, D. B., & Yüzbaşioğlu, N. (2024). Productivity in professional tourist guides: a scale development study with mixed-methods sequential exploratory design. Anais Brasileiros de Estudos Turísticos, 14(01), 1–11.

[https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11093431]

-

Scannell, L., & Gifford, R. (2017). Place attachment enhances psychological need satisfaction. Environment and Behavior, 49(4), 359–389.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916516637648]

-

Scheyvens, R., & Hughes, E. (2021). Can tourism help to “end poverty in all its forms everywhere”. The challenge of tourism addressing SDG1. In Activating critical thinking to advance the sustainable development goals in tourism systems. 215-233. Routledge.

[https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003140542-13]

- Schrems, S. H. (1987). Teaching School on the Western Frontier: Acceptable Occupation for Nineteenth Century Women. Montana: The Magazine of Western History, 37(3), 54–63.

- Silva, D., & Mendis, B. A. K. M. (2017). Women in tourism industry–Sri Lanka. Journal of Tourism, Hospitality and Sports, 25, 65–72.

- Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority. (2018). Annual statistical report. Retrieved June 21st, 2024, from https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-bd&q=Sri+Lanka+Tourism+development+authority.+%282018%29.+Annual+statistical+report+

- Tourismtiger. (n.d.). An Inside Look At Being A Female Tour Guide. Retrieved February 10, 2024, from https://www.tourismtiger.com/blog/an-inside-look-at-being-a-female-tour-guide/

-

Tubang-Delgado, M. B. (2024). Grammatical competence of tourism frontliners in an eco-adventure tourist destination: Basis for competency development project, International Journal of Research Publications. 140(1), 497–505.

[https://doi.org/10.47119/IJRP1001401120246003]

- UN Tourism. Women’s empowerment and tourism. UN Tourism. Retrieved February 10, 2024, from https://www.unwto.org/gender-and-tourism

- United Nations. Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for Sustainable Development. United Nations. Retried February 12, 2024, from https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda

-

Vandegrift, D. (2008). This isn't paradise—I work here global restructuring, the tourism Industry, and women workers in Caribbean Costa Rica. Gender and Society, 22(6), 778–798.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243208324999]

- World Bank. (2022). Female labour force participation. Retrieved June 21, 2024, from https://genderdata.worldbank.org/data-stories/flfp-data-story/

- World Economic Forum. (2021). The travel and tourism competitiveness report. Retrieved March 30, 2024, from https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Travel_Tourism_Development_2021.pdf

- World Travel and Tourism Council. (2022). Travel and Tourism, Economic Impact 2022. Retrieved February 20, 2024, From World Travel and Tourism Council https://wttc.org/Portals/0/Documents/Reports/2022/EIR2022-Global%20Trends.pdf

Biographical Note: Ruwanthika Jayaweera completed her Ph.D. at the Faculty of Management and Finance, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka. Her research interest focuses on work life balance, gender, career advancement and self-determination. Email: jruwanthika@yahoo.com

Biographical Note: Thilakshi Kodagoda is a Full-time Professor in Human Resources Management at the Faculty of Management and Finance, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka. Her research focuses on a current of labor market issues, including the combination of paid and unpaid work, work-life balance policies, gender at workplace, women in small business, positive psychological capital and Millennials’ behavior at work. She is also interested in qualitative methods. Email: thilakshi@hrm.cmb.ac.lk