Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Lifetime Prevalence of Domestic Violence against Women in Iran

Abstract

Domestic violence against women is a major problem worldwide. This study aimed to provide a more accurate lifetime prevalence estimation of violence against women in Iran. The prevalence rate of different types of the violence until the end of 2013 were extracted from scientific databases and combined using Random model in stata 10. The best estimate of the general prevalence of violence against women in Iran was 48.87%. Place, time, and sample size were the main factors causing heterogeneity. Although the proposed statistics are not generalizable to the entire population of Iranian women, the prevention of this social disturbance in Iran is urgent.

Keywords:

systematic review, meta-analysis, domestic violence, womenIntroduction

Domestic violence against women has been known as a major public health problem worldwide. This has led to widespread efforts by activists, researchers, and policy makers to develop strategic planning in order to protect women and prevent violence in their lives (Pallitto, García-Moreno, Jansen, Heise, Ellsberg, & Watts, 2013). In a general sense, domestic violence has been defined as the violence against women, men, and children in a family environment. Another proposed term for this is domestic abuse. Domestic violence against women is considered to be a pattern of compulsory control in an intimate relationship such as marriage, friendship, or exclusive sexual relationship (Dugwen, Hancock, Gilmar, Gilmatam, Tun, & Maskarinec, 2013). In this paper, this topic is referred to as “spousal abuse,” or “marital abuse.” The most common form of violence against women in Iran is the violence imposed by marriage.

The World Health Organization considers violence against women as the main cause of anxiety, depression, suicidal thoughts, and stress among women (Ludermir, Schraiber, D'Oliveira, França-Junior, & Jansen, 2008). On the basis of a WHO report on “Global and regional estimates of violence against women,” domestic violence includes physical, sexual, and/or emotional violence or abuse consisting of a woman’s being humiliated, insulted, intimidated, or threatened and subjected to controlling behaviors by a close or ex-partner, such as not being allowed to see friends or family (Coker, Smith, Bethea, King, & McKeown, 2000; Kocacik & Dogan, 2006; Jewkes, Dunkle, Nduna, & Shai, 2010; World Health Organization, 2013). Each year, domestic violence results in nearly 1,200 deaths and 2 million injuries among women (Baker, Billhardt, Warren, Rollins, & Glass, 2010).

According to a WHO systematic review (World Health Organization, 2013), the global prevalence of physical and/or sexual intimate-partner violence among all ever-partnered women was 30.0%. In this comprehensive study, the prevalence was reported highest in the WHO African, Eastern Mediterranean and South-East Asia Regions (Table 1).

Lifetime Prevalence of Physical and/or Sexual Intimate Partner Violence among Ever-partnered Women by WHO Region

In most communities such as Iran, the study of domestic violence against women is challenging as it mostly happens in the private sphere of the family. Most women feel ashamed, embarrassed, and guilty, or fear the social consequences of a perceived betrayal of the woman’s husband and family or the lack of support in the case of the woman’s leaving home or changing position, so they do not report this violence (Usta, Farver, & Pashayan, 2007). Statistics on the prevalence rate of this problem vary worldwide and researchers have cited different rates. This difference in statistics is due to differences in the definition of violence, time, and condition of questioning the women, as well as the studied populations (Bacchus, Mezey, & Bewley, 2004).

A simple review of existing documents shows that the prevalence of violence among Iranian women is very different. Detailed statistics of domestic violence have not been reported in Iran and different studies do not show similar results (Table 2). Also previous studies have been limited to a particular region such as a city or province. So a systematic review of these documents and their combination can provide a comprehensive estimation of the scale of this problem in Iranian society. Therefore, because this study identifies different types of violence and its intensity in Iranian families and detects effective underlying factors, it intends to provide a comprehensive estimation of the characteristics of this phenomenon among Iranian women.

Materials and Methods

In this study, the integrated lifetime prevalence of various types of domestic violence against Iranian women was investigated and determined by using a systematic review of existing documents without time limit until the end of 2013 and by subjecting the data provided by these documents to meta-analysis techniques, based on the overall prevalence rate provided in the retrieved articles and also the prevalence rate of psycho-emotional, physical, sexual, verbal, and economic violence. Thus, all available sites of articles, theses and national conferences and also international sites of PubMed, Science direct/ISI and Scopus were explored. The mechanism of searching papers was mainly performed using a systematic search of Persian keywords including domestic violence, family violence, physical violence, verbal violence, psycho- emotional violence, economic violence, or sexual violence, together with alternative combinations of abuse or spouse abuse or misbehavior and women and prevalence and their Latin equivalents with all potential, principal, and critical combinations.

Selection Criteria and Investigation of Articles Quality

Once the search was completed, a list consisting of titles and abstracts of all articles in above-mentioned database was prepared and investigated separately by the researcher in order to determine and select relevant topics. Then the relevant articles were included in the process independently. Articles were included based on whether their titles referenced an estimation of the lifetime prevalence of various types of violence against women. In the second stage, after title-based determination of relevant investigations, the researcher evaluated selected abstracts of different papers by using the STROBE1 checklist, which is a famous international standard checklist for quality assessment of observational studies. This checklist includes 43 different sections and evaluates various aspects of methodology, including sampling methods, measurement of variables, statistical analysis, and targets of study. Minimum and maximum scores of this checklist were 40 and 45. Superior papers which received the minimum score (40 points) were finally included in the study and their relevant data were extracted for the meta-analysis process (Bagheri et al., 2011). Indeed, investigations that obtained at least the minimum score in the citation and application of appropriate sampling method, accurate measurement of the research parameter and its citation, application of proper analysis along with sampling design and method in the research and necessary measures to control the bias factors, reference to the design method used in the study, and adequate generalization of findings were included in the meta-analysis process.

Based on the explanations provided in the first stage of the search, 112 articles were found. After reviewing the titles, 80 related articles were identified and included in the second phase of abstract evaluation and 28 unrelated articles were excluded. 52 proper articles were finally selected to be included in meta-analysis stage.

According to the purpose of the study and the meta-analysis determination of the prevalence of violence against Iranian women, studies with no reference to the research main items such as violence prevalence or sample size were excluded from investigation process (exclusion criteria). Accordingly, general prevalence of violence was mentioned in 24 articles and psycho-emotional, physical, sexual, economic, and verbal violence were separately mentioned in 30, 33, 21, 8 and 3 articles, respectively. It should be noted that since the original details of data related to all individuals investigated in all 52 studies were not available, required data including general and separated prevalence, sample size, place and time of the study, and other necessary information were used as aggregate data. Also, according to the analyzed data related to the prevalence of violence among women and the exact consideration of checklist parameters in the quality control stage in order to select the eligible studies, there was no need for determining publication bias and drawing a funnel plot (Bagheri et al., 2011).

Statistical Analysis

In this section, first all rates of violence prevalence from all descriptive studies were collected. Then the variance of each study was determined using the binomial distribution formula for each prevalence. In the second stage, based on the variance, the weight of each study was calculated using the fix effect model as the inverse variance. Then, provided that the weight for each study could be calculated, obtained prevalence rates were mixed using random effect method of DerSimonian and Laird and general and separated prevalence of violence were calculated. Finally, the heterogeneity index was determined by a heterogeneity test (Cochran Q and I2 statistics) between studies. After confirming the heterogeneous nature of the studies, the best estimate of prevalence was calculated based on the random effect model. Bayesian Analysis was used to minimize random variation between estimates of prevalence. Finally, the effect of variables such as age, duration of study, place of study, method of study, and sample size was investigated in different studies suspected of causing heterogeneity in the study using meta-regression method and stata10 software. Also in this statistical analysis, t2 index was calculated by the restricted likelihood method as the estimator of heterogeneity (Bagheri et al., 2011).

Results

Total numbers of women in all 52 articles were 17512 people. Average age in the studies was 33.56 ± 5.9 years. Details of data related to these investigations are presented in Table 3 based on the general and separate prevalence. As was mentioned before, according to the findings of the studies and the various prevalence investigated in the early articles, differ prevalences were classified based on general prevalence as psycho-emotional, physical, sexual, verbal, and economic violence. In their study, Esfandabad and Emamipoor (2004) reported the highest and lowest general prevalence of violence in Tehran belongs to women aged between 18 to 40 with 81.7% and 18.7%, respectively. Also, maximum and minimum rates for psycho-emotional, physical, sexual, verbal, and economic violence were 98.9 and 15%, 95.4 and 5.7%, 95.2 and 4.36%, 69.5 and 45.7%, and 72 and 2.78%, respectively (Table 3).

After preliminary calculations, the heterogeneity index (Q) was calculated as 301.32 for general prevalence of violence, 787.53 for psycho- emotional violence, and 983.49 for physical violence, 531.4 for sexual violence, and 97.29 for economic violence. Based on the calculated heterogeneity index, t2 was obtained as 617.014 for general violence and 25231.26-73118.42, 2905.70, and 179.70 for other separate violence respectively. A random effect model was used to show high heterogeneity between findings in all subsequent stages. It should be noted that among all separate kinds of violence dealt with in this study, verbal violence due to the number of its sample was the only non-heterogeneous one, and this was referenced to previous statistical analysis based on the fix effect model. Therefore the estimation of the prevalence of verbal violence with a confidence interval of 95% (54.25-59.1) was calculated and reported as 57.17% based on the fix effect model (Q=2.66, t2=0). (Table 4)

In the calculation of final and original estimation of prevalence rate based on the random effect model, original estimation of prevalence of violence in Iran was calculated as follows: general violence 48.87% (Q=14.55, t2=0) with a confidence interval of 95% (43.21-50.22), psycho- emotional violence 53.17% (Q=0.62, t2=0) with a confidence interval of 95% (49.3-57.21), sexual violence 30.8% (Q=3.2, t2=0) with a confidence interval of 95% (24.36-33.7), physical violence 35.51% (Q=-.027, t2=0) with a confidence interval of 95% (31.6-39.71), and economic violence 23.39% (Q=13.95, t2=7.98) with a confidence interval of 95% (19.5-26.66). (Table 4)

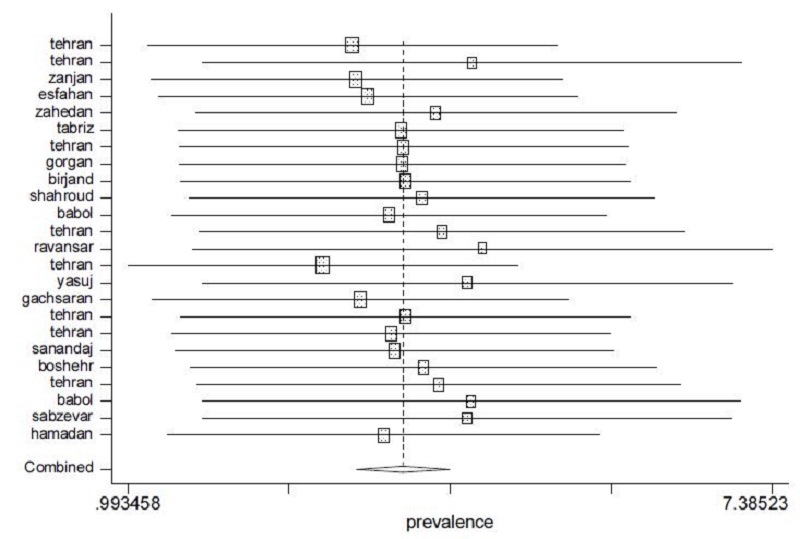

Due to the heterogeneous nature of the findings, factor(s) causing prevalence rate heterogeneity were determined using meta-regression models. As is seen in Figures 1-3, there are many differences between reported prevalence of various studies in Iran. The amount of t2 in meta-regression model in the absence of any co-variant was equal to 0.91 for general violence and 0.58, 0.85, 0.39, and 0.46 for psycho-emotional, physical, sexual, and economic violence respectively. In order to find potential roots of differences, variables like age, time of study, place of study, method of study, and also sample size suspected of causing heterogeneity included in the moment based meta-regression analysis as the co-variance. These analysis findings showed that inclusion of variables of place, time, and sample size would reduce t2 of general prevalence of violence to 0.41, 0.3, and 0.25 respectively. The inclusion of variables of place and time of studies would cause a reduction in t2 for psycho-emotional violence to 0.21, physical violence to 0.39, sexual violence to 0.19, and economic violence to 0.11 (p<0.001). (Table 5)

Accumulation Curve for Prevalence Rate of General Domestic Violence against Iranian Women based on Authors

Accumulation Curve for Prevalence Rate of Psycho-emotional Violence against Iranian Women based on Place

Raw and Adjusted Effects of Potential Factors Effective on Causing Heterogeneity in General and Separated Prevalence of Domestic Violence against Iranian Women (Meta-regression Model Findings)

In other words, the variables of place, time and sample size have a significant effect in reducing the heterogeneity at all levels, including general and separate prevalence of violence. They were introduced as the predominant factors causing the heterogeneity in studies, which could justify part of the difference between the findings of studies. In this between, the variables of method of study and average age had no effect on causing heterogeneity in findings (p=0.46).

In this study, I2 index was also calculated in random effect model for general prevalence as 58% and for psycho-emotional, physical, sexual, and economic violence as 45.43%, 17.26%, 5.24%, and 49.82% respectively. This indicator shows that in each violence, the level of observed differences between indicators of various studies is due to the heterogeneous nature of studies.

Discussion

The findings of this study indicate that the best estimate of the prevalence of general violence against Iranian women is 48.87%, and for psycho- emotional, sexual, physical, verbal and economic violence the prevalences are 53.17%, 30.8%, 35.51%, 57.17% and 23.39%, respectively. Also, variables such as place, time, and sample size show significant effects on the reduction of heterogeneity in all types of violence.

In this study, the prevalence rate of violence was generally divided into five categories: psycho-emotional, physical, sexual, verbal and economic violence. In the literature review it was revealed that some results have conflicting and different prevalence. In these investigations, the highest reported rate for general prevalence was observed in a study conducted on 200 married women in 2010 in the city of Ravansar in Kermanshah province. The general prevalence rate of violence reported in these studies was 91%. The lowest general prevalence rate of violence belonged to a research performed on 500 pregnant women in 2007 in Gachsaran in Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad province in which the prevalence rate was reported as 27.1%. The cultural context of Kermanshah province and Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad province, due to the presence of the Kord and Lor ethnic groups, is considered to be one of the most genteel and respectable social and ethnic contexts in Iran. However it is not exactly clear, despite the similar ethnicity and cultural context, why the highest prevalence of violence against women is observed in one province and the lowest in another. Part of this is due to the fact that the confined population instead of the general population of women was investigated in Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad province; the low prevalence rate was therefore reported for only a subgroup of women (pregnant women). Another problem with these results is that, according to documented reports, the suicide rate in western provinces such as Ilam, Lorestan, Hamedan, and Kermanshah is higher than in other provinces (Rezaeian, 2013). These two factors could possibly be linked to one another. Meanwhile, there might be a reasonable direct and justifiable potential relationship between violence and the risk of suicide or self-injury, but understanding its mechanism requires more specialized studies. Also, the relationship between the economic and living status of families in these areas should be examined. This would be necessary because, based on Anbari and Bahrami (2011), there is a direct and significant relationship between violence, poverty, and suicide. In fact, according the results of this study, poverty has the greatest impact on suicide through domestic violence.

An investigation of 450 women who were referred to police stations and family courts in Tehran in 2003 indicated that among various kinds of domestic violence, psycho-emotional violence with the reported prevalence of 98.9% had the highest rate. The lowest prevalence rate of 15% belonged to a study in Babol that was performed on 2,400 married women who were referred to general clinics in 2005. The highest reported rate of 94.7% on physical violence was related to a study performed on 450 victim women in Tehran in 2003. The lowest rate of this violence with a sample size of 414 individuals was reported as 5.7% in Birjand in 2008.

Among the findings of sexual violence, the highest reported rate was related to a study with a sample size of 290 women and reported rate of 95.2 that was conducted in Tehran in 2008. On the other hand, the lowest rate of sexual violence was seen in a study performed on 383 urban women in 2007 in Lorestan. In this study, the reported rate of sexual violence was 4.36.

If we concentrate on the above statistics, it becomes evident that the majority of violence have been recorded and reported in Tehran. The speed of social changes in the country and subsequently in large cities, have had some consequences on people's lives. The increasing level of expectations on one hand, and limited economic-social facilities on the other hand, can create conflicts and disputes in the family. Also population growth and its young demographic in Iran has developed new problems and requirements. The process of changing values vis à vis traditional norms has caused an increase in social tensions and conflicts in most parts of the country. In this context, the socio-cultural constraints and economic confinements and thus the prevalence of different kinds of social disorders such as crime and addiction could create conflicts and disagreements between social groups like families (Anbari & Bahrami, 2011). These kinds of disorders, which are greater in large cities like Tehran than in other traditional smaller cities, give rise to various kinds of violence.

All the studies have mentioned the ratio of psycho-emotional and physical violence. While most studies have ignored verbal and economic violence, findings suggest that the highest and lowest rate of verbal violence with 69.5% and 45.7% have been reported in Yasuj and Birjand respectively. However, the highest rate of economic violence, with a prevalence of 72%, relates to Semnan in 2003 and the lowest reported rate of economic violence, with the prevalence of 2.78, belongs to a study conducted in Lorestanin 2007.

In our current study it was also found that despite various statistics of domestic violence, these studies have mentioned common contextual factors such as low income, education and age (Mousavi & Eshaghian, 2004; Narimani & Aghamohammadian, 2005; Jokar, Garmaznejad, & Sharifi, 2005; Saberian, Atashnafas, & Behnam, 2005; Bayati & Shamsi, 2009; Ghazanfari, 2010; Razzaghi, Tadayyonfar, & Akaberi, 2010; Atefvahid, Ghahari, Zareidoost, Bolhari, & Karimi-kismi, 2011; Nouhjah et al., 2011; Baheri, Ziaie, & Zeighamimohammadi, 2012; Elahi & Alhani, 2013). Since education will lead to awareness and skills required for dealing with life problems, low education status is an effective factor in relationships that exhibit abusive behavior. Education can play an important role in the quality of marital life. However, male unemployment and low income are associated with the occurrence of abuse. Exhaustion from lack of resources creates conflicts, vague expectations, and inappropriate cycles of domestic arguments, all of which can induce violence.

Meanwhile the results of our study showed that among all types of domestic violence, including psycho-emotional, physical, sexual, verbal, economic violence, the effective contextual factors of each are not segregated separately. Therefore, this issue needs more investigations in future research, and factors effecting psycho-emotional violence, for example, should be discriminated from factors causing economic violence.

According to the meta-analysis findings, possible reasons for different statistics of violence in various studies could stem from the different conditions of investigated samples. For example, the high rate of psycho- emotional violence in one study was related to married or pregnant women who were victims of violence and referred to family courts (Atef Vahid, Ghahari, Zareidoost, Bolhari, & Karimi-kismi, 2011). In contrast, there were studies with low rate of violence in women who were referred to counseling clinics or health centers (Faramarzi, Esmaelzadeh, & Mosavi, 2005; Moasheri, Miri, Abolhasannejad, Hedayati, & Zangoie, 2012). Therefore self-reports and women’s conceptualization of violence somehow played a role in proposing violence rates.

Regarding the different responses of these investigations, it could be possible that consideration of different geographic areas such as small towns or provinces in some research will lead to the reflection of different statistics on violence. As in research about a sample in Tehran, proposed statistics had more homogeneity and proximity.

One of the constraints of this research could be that different kinds of domestic violence were not separated in most studies and were summarized in two forms: psycho-emotional and physical violence. Besides, some important characteristics such as age or even general prevalence rate, which are considered to be highly significant factors in exploring domestic violence, were ignored by different authors. Another restriction of this study is the diversity of reports on the violence prevalence such that standard scales were used in some research and researcher-made tools were applied in others. Another important limitation that makes the interpretation and generalization of the results difficult is that some of the qualified studies were conducted on certain groups, such as pregnant women or women with addicted husbands. Therefore specific statistics on the prevalence rate of various kinds of violence against ordinary women of the society were not found. Of course, this does not imply that violence against ordinary women does not exist, but rather that, depending on the social and cultural conditions of Iranian religious society, these kinds of studies about violence against ordinary women are not conducted or that this kind of violence is not reported.

Conclusion

Although various types of domestic violence are common in Iran society and are traceable among different social groups despite social affairs and various customs, different researchers have not yet reached a consensus on the appropriate prevalence and statistics. Because they have partially addressed the issue, thus proposed statistics are not extensible to all Iranian women.

Due to its attempt at a systematic review, this study is likely the most comprehensive investigation on the prevalence of domestic violence in Iran. Psycho-emotional, physical, and sexual violence were three subjects with the most attention in the study. Consequently, conducting a similar meta-analysis on other kinds of violence and investigating the reason for their diminished role in various studies is recommended as a necessary complementary action for future investigations. An important issue in this study is the consideration of the actual confounding role of social variables with respect to different cultural and demographic context, including mean age and severity of violence based on the referral to legal authorities or prevention organizations.

Thus, it should be said that a codified plan and the cooperation of all organizations are required for the prevention of domestic violence in Iran society. The family disciplinary entity should be the main focus of educational strategies: addressing the effective role of mothers will act like a vaccine for such problems in the society. Later on, the consideration of financial support in education, especially in schools and mass media, and the explanation of right communication patterns could be extremely effective in the prevention of domestic violence. In addition to educational strategies, consideration and development of psychotherapy and counseling services are situated next in importance. Finally, the enrichment of entities involved in women's rights and family health, including jurisdictions as the legal authorities, social emergency and the universities of medical sciences as the educational and information authorities, will lead to the planning and identification of the most important cultural and social roots of the problem and also may engender strategies to control or solve the issue.

Notes

References

- Anbari, M., & Bahrami, A., (2011), Effects of poverty and violence of suicide in Iran, Iranian Journal of Social Problems, 1(2), p1-30, (In Persian).

-

Ardabily, H. E., Moghadam, Z. B., Salsali, M., Ramezanzadeh, F., & Nedjat, S., (2011), Prevalence and risk factors for domestic violence against infertile women in an Iranian setting, International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 112(1), p15-17.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.07.030]

- Atefvahid, M. K., Ghahari, S. H., Zareidoost, E., Bolhari, J., & Karimi-kismi, E., (2011), The role of demographic and psychological variables in predicting violence in victims of spouse abuse in Tehran, Iranian Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 63(4), p403-411, (In Persian).

- Azadeh, M., & Dehghanfard, R., (2006), Domestic violence on women in Tehran: The role of gender socialization, Women in Development and Politics, 4(1), p159-179, (In Persian).

-

Bacchus, L., Mezey, G., & Bewley, S., (2004), Domestic violence: Prevalence in pregnant women and associations with physical and psychological health, European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 113(1), p6-11.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-2115(03)00326-9]

- Bagheri, P., Haghdoost, A., Dortaj, bari, E., Halimi, L., Vafaei, Z., Farhangnia, M., & Shayan, L., (2011), Ultra analysis of prevalence of osteoporosis in Iranian women: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis, Iranian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, 3(13), p315-338, (In Persian).

- Baheri, B., Ziaie, M., & Zeighamimohammadi, S. H., (2012), Frequency of domestic violence in women with adverse pregnancy outcomes (Karaj 2007-2008), Scientific Journal of Hamadan Nursing & Midwifery Faculty, 20(1), p31-38, (In Persian).

- Baker, C. K., Billhardt, K. A., Warren, J., Rollins, C., & Glass, N. E., (2010), Domestic violence, housing instability, and homelessness: A review of housing policies and program practices for meeting the needs of survivors, Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15(6), 430.439.

- Bayati, A., & Shamsi, M., (2009), Prevalence of intimate partner violence and views of women on adopting ways to fight against it in Arak city, Iran, Journal of School of Public Health and Institute of Public Health Research, 7(3), p83-91, (In Persian).

-

Coker, A. L., Smith, P. H., Bethea, L., King, M. R., & McKeown, R. E., (2000), Physical health consequences of physical and psychological intimate partner violence, Archives of Family Medicine, 9(5), p451-457.

[https://doi.org/10.1001/archfami.9.5.451]

- Dolatian, M., Gharahcheh, M., Ahamadi, M., Shams, J., & Alavimajd, H., (2009), Evaluation of health outcomes with relation to intimate partner abuse among pregnant women attending Gachsaran Hospitals in 2007, Qom University of Medical Sciences Journal, 2(4), p43-50, (In Persian).

- Dolatian, M., Hesami, K., Shams, J., & Alavimajd, H., (2008), Evaluation of the relationship between domestic violence in pregnancy and postnatal depression, Scientific Journal of Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences, 13(2), p57-68, (In Persian).

- Dugwen, G. L., Hancock, W. T., Gilmar, J., Gilmatam, J., Tun, P., & Maskarinec, G. G., (2013), Domestic violence against women on Yap, Federated States of Micronesia, Hawaii Journal of Medicine & Public Health, 72(9), p318-322.

- Elahi, N., & Alhani, F., (2013), Frequency of intimate partner abuse referred to Ahvaz Health Center and related factors, Jentashapir Journal of Health Research, 11(5), p477-487, (In Persian).

- Esfandabad, S. H., & Emamipoor, S., (2004), A survey on prevalence of wife abuse and its influencing factors, Women in Development & Politics, 1(5), p59-82, (In Persian).

- Faramarzi, M., Esmaelzadeh, S., & Mosavi, S., (2005), Prevalence and determinants of intimate partner violence in Babol city, Islamic Republic of Iran, Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 11(6), p870-879.

- Faramarzi, M., Esmaelzadeh, S., & Mosavi, S., (2005), Prevalence, maternal complications and birth outcome of physical, sexual and emotional domestic violence during pregnancy, Acta Medica Iranica, 43(2), p115-122, (In Persian).

- Ghazanfari, F., (2010), Effective factors on violence against women in Lorestan county towns, Yafteh, 44(2), p5-11, (In Persian).

-

Jewkes, R. K., Dunkle, K., Nduna, M., & Shai, N., (2010), Intimate partner violence, relationship power inequity, and incidence of HIV infection in young women in South Africa: A cohort study, The Lancet, 376(9734), p41-48.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60548-X]

- Jokar, A., Garmaznejad, S., & Sharifi, M., (2005), A study on prevalence rate of intimate partner violence among women attending Yasuj Health Centers, Armaghane-danesh, 10(37), p81-88, (In Persian).

- Kazemi, F., (2005), Study on prevalence, causes and outcomes of domestic violence against pregnant women in hospitals of Tehran Medical Universities, Master’s thesis, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, (In Persian).

- Kocacik, F., & Dogan, O., (2006), Domestic violence against women in Sivas, Turkey: Survey study, Croatian Medical Journal, 47(5), p742-749.

-

Ludermir, A. B., Schraiber, L. B., D, liveira, A. F., Franca-Junior, I., & Jansen, H. A., (2008), Violence against women by their intimate partner and common mental disorders, Social Science & Medicine, 66(4), p1008-1018.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.10.021]

- Moasheri, N., Miri, M. R., Abolhasannejad, V., Hedayati, H., & Zangoie, M., (2012), Survey of prevalence and demographical dimensions of domestic violence against women in Birjand, Modern Care, Scientific Quarterly of Birjand Nursing and Midwifery Faculty, 9(1), p32-39, (In Persian).

- Mohammadi, F., & Mirzaei, R., (2012), Social factors affecting violence against women, case study: The city of Ravansar, Journal of Iranian Social Studies, 6(1), p101-129, (In Persian).

- Mousavi, M., & Eshaghian, A., (2004), Spouse abuse in Isfahan, Iran 2002, Forensic Medicine, 10(33), p48-59, (In Persian).

- Narimani, M., & Aghamohammadian, H. R., (2005), Evaluation of male violence against women and its related factors among families residing in the city of Ardabil, The Quarterly Journal of Fundamentals of Mental Health, 7(28), p107-113, (In Persian).

- Nouhjah, S., Latifi, M., Haghighi, M., Eatesam, H., Fatholahifar, A., Zaman, N., Farokhnia, F., & Bonyadi, F., (2011), Prevalence of domestic violence and its related factors in women referred to health centers in Khuzestan Province, Journal of Kermansha University of Medical Sciences, 51(4), p278-286, (In Persian).

-

Pallitto, C. C., Garcia, oreno, C., Jansen, H. A., Heise, L., Ellsberg, M., & Watts, C., (2013), Intimate partner violence, abortion, and unintended pregnancy: Results from the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence, International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 120(1), p3-9.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.07.003]

- Razzaghi, N., Tadayyonfar, M., & Akaberi, A., (2010), The prevalence of violence against wives and relevant factors in married women admitted to health and treatment clinics in Sabzevar, Journal of Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, 55(1), p39-47, (In Persian).

- Rezaeian, M., (2013), Comparing the statistics of Iranian Ministry of Health with data of Iranian Statistical Center regarding recorded suicidal cases in Iran, Health System Research, 8(7), pS1190-S1196, (In Persian).

- Saberian, M., Atashnafas, E., & Behnam, B., (2005), Prevalence of domestic violence in women referred to the heath care centers in Semnan, Koomesh, 6(2), p115-122, (In Persian).

- Taherkhani, S., Mirmohammadali, M., Kazemnejad, A., Arbabi, A., & Amelvalizadeh, M., (2010), A survey on prevalence of domestic violence against women and relationship with couple’s characteristics, Forensic Medicine, 54(2), p123-129, (In Persian).

- Usta, J., Farver, J. A. M., & Pashayan, N., (2007), Domestic violence: The Lebanese experience, Public Health, 121(3), 208.219.

- World Health Organization, (2013), Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and nonpartner sexual violence, Italy.

- Yazdkhasti, B., & Shiri, H., (2009), Values of patriarchy and violence against women, Women's Studies, 6(3), p55-79, (In Persian).

Biographical Note: Akram Kharazmi is a research assistant at Social Development & Health Promotion Research Center, Gonabad University of Medical Science, Gonabad, Iran. E-mail: kharazmiak@gmail.com

Biographical Note: Vajihe Armanmehr is a research assistant at Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Gonabad University of Medical Science, Gonabad, Iran. E-mail: varmanmehr@gmail.com

Biographical Note: Noorallah Moradi works at Social Development & Health Promotion Research Center, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran. E-mail: noorallah.moradi@gmail.com

Biographical Note: Pezhman Bagheri works at Department of Social Medicine, Noncommunicable Diseases Research Center, Fasa University of Medical Science, Fasa, Iran. E-mail: bpegman@yahoo.com