Not Separate but Unequal

In Asia, where increasing numbers of women have been entering the workforce in recent decades, gender inequality in terms of career progression seems to be particularly prevalent. Although many studies have investigated the impact of issues such as occupational gender typing, tokenism, and pay inequity on Asian women at the workplace, the role of the individual’s early career experiences in organizations has received little attention. Organizational socialization forms a significant part of the individual’s early work experiences, and socialization can set the tone for the individual’s progress through the organization and career. This paper addresses two questions pertaining to organizational socialization and gender in the Asian context. First, the study investigated if female newcomers to organizations receive the same amount of socializing influences as their male counterparts. Secondly, the study investigated the moderating effect of gender on socialization practices and socialization outcomes. The study was conducted using a sample of business graduates of an Asian university. Results show that female newcomers receive less social support and mentoring in the form of social tactics than their male counterparts. Results also show that gender moderates the effects of socialization tactics on role outcomes. Female newcomers tend to benefit more through the mentoring and interaction provided through social tactics while male newcomers seem to benefit from structured learning.

Keywords:

Gender and organizational socialization, socialization and gender, socialization tactics, business and genderIntroduction

Over the last two decades, more women have been ascending to corporate and political leadership roles all over the world (Eagly & Carli, 2007). Some influential authors have even argued that gender inequity in the workplace may be on the wane, with socialization patterns for men and women becoming more uniform (Alvesson & Billing, 1992). Recent reviews, however, indicate that gender inequality at the workplace persists across a broad spectrum of professions, experience and organizational levels (King, Hebl, George, & Matusik, 2010). In Asian countries, where the participation of women in the workforce has grown in recent years, gender inequality in terms of career progression seems to be particularly prevalent despite evidence that Asian women have the same motivations and aspirations as men do; and in many such instances, women are equally qualified and competent (Guo & Liang, 2012; Gunkel, Lusk, Wolff, & Li, 2007; Kang & Rowley, 2005).

In her seminal work on gender inequality, Kanter (1977) noted that career prospects of women and other under-represented groups are often stymied right at the point of entry to the organization. Exclusionary socialization practices are often cited as the reason for persistent gender inequity. Organizational theorists make a similar point: that women face several structural and cultural barriers to organizational socialization and adjustment (Noe, Greenberger, & Wang, 2002; Ibarra, 1993).

Organizational socialization is the process through which a newcomer acquires and applies the requisite knowledge and skills for the new role, understands the organization’s culture, participates in the networks, and becomes an insider (Saks, Uggerslev, & Fassina, 2007). Effective socialization and a sense of fit with the organization play a significant role in the individual’s persistence in a career and eventual success (Cable & Parsons, 2001). Early experiences signal to organizational newcomers their status and acceptance in the organization, and set career expectations that could result in a virtuous or vicious cycle.

Inequality in training and orientation, career path clarification, role learning, social support and mentoring are tantamount to exclusion. Exclusion hampers adjustment, with a longer-term impact on organizational commitment and career progress. Earlier research on gender has shown that socialization experiences of women are often marked by a lack of equal access to mentors, networks, co-worker support, and training, depriving them of equal opportunity for career enhancing strategies (Forret & Dougherty, 2004; Kanter, 1977; Kirchmeyer, 1995).

In recent years, organizations have been increasingly sensitive to recruitment and adjustment needs of under-represented groups such as ethnic minorities and women. This resulted in inclusive policies and affirmative action all over the world (Bailyn, 2003; Cho, Kwon, & Ahn, 2010). At the level of implementation, however, incumbents and seniors serve as socializing agents in most organizations and professions. Several authors have argued that this perpetuates the status quo.

Persistent exclusionary practices appear to be structurally and culturally embedded (Küskü, Özbilgin, & Özkale, 2007; Prokos & Padavic, 2002). Structural barriers may take the form of institutionalized training and induction practices that unconsciously perpetuate and emphasize masculinity, particularly in male dominated fields (Bernstein & Russo, 2008; Dryburgh, 1999; Guo & Liang, 2012). Organizational cultures reinforce the barriers against women by excluding them from the mainstream discourse. In her critical and autobiographical narrative of organizational socialization, Allen (1996) reflected that women often do not go through stages of socialization; rather, they go through a “continuous process of being marked as other and excluded” (p. 260). In a similar vein, Rutherford (2011) writes: “A board of 12 men might, in principle, believe that having several women around the table would enhance their discussions and benefit the business. However, on a deeper level they might also have fears of their in-group being broken... their incompetence exposed...” (p. 23).

Even in more amicable environs, issues of interpersonal comfort and benevolent forms of stereotyping preclude effective mentoring for women newcomers (Allen, Day, & Lentz, 2005). A consequence of exclusion is that the newcomer may not receive the same quality and quantity of socializing influences (Forret & Dougherty, 2004). Thus, integrated yet unequal socialization sets women up for lack of progress on an equal footing with the majority, if not for failure.

On the other hand, learning theorists have argued that there are significant differences in learning styles between the sexes (Baxter Magolda, 1998; Severiens & Ten Dam, 1998). If this is indeed the case, and socialization processes use a dominant male-oriented paradigm, learning and adjustment outcomes for women may not be the same as for men. Thus, learning style and organizational socialization practices could impact the acquisition of role-specific knowledge by newcomers, and consequently, their adjustment, performance, and career expectations.

While the foregoing arguments suggest a persistent and systematic gender bias in organizations, research on organizational socialization with respect to gender is scarce (with the exception of research on mentoring), particularly in the Asian context. Few studies have investigated the existence of exclusion and gender bias in the multitude of socialization practices across organizations. There is also little understanding of the consequences of bias in terms of mastering the job, adjustment to the workplace, and organizational commitment. Extensive research on gender relations in mentoring, an important element of socialization, remains inconclusive with mixed evidence (Allen & Eby, 2004; Turban, Dougherty, & Lee, 2002). There are several ethnographic studies that present rich detail of women’s organizational socialization experiences (e.g. Moore, 1999; Prokos & Padavic, 2002). However, they have not examined the question of socialization outcomes in terms of role learning and commitment. It is the mastery of one’s role and work environment that drives career progress.

This paper addresses two questions pertaining to organizational socialization and gender. First, the study investigated if female newcomers to organizations receive the same amount of socializing influences as their male counterparts. Secondly, the study investigated the moderating effect of gender on socialization practices and socialization outcomes. The study was conducted using a sample of business graduates of a Southeast Asian university. Data was collected over a period of six months. Role learning is the most important outcome of organizational socialization, and this study incorporated role clarity outcomes, role conflict, role orientation, and organizational commitment as the outcome variables.

Literature Review and Hypotheses

Organizational socialization is the process through which newcomers acquire contextual knowledge, role specific knowledge and job skills, and integrate into the organization (Louis, 1980). Van Maanen and Schein (1979) identified six tactics used by organizations to socialize newcomers: collective-individual, formal-informal, investiture-divestiture, serial- disjunctive, sequential-random, and fixed-variable. Jones (1986) further grouped the six socialization tactics into three groups on the basis of their functions: contextual, social, and content. Contextual tactics refer to the shared and formal learning experiences a newcomer encounters during socialization. When organizations deploy contextual tactics, newcomers are put through a common training and orientation that not only imparts uniform knowledge but also serves to develop bonding between members of the cohort. On the other hand, some organizations may adopt the other extreme of a “sink-or-swim” approach, leaving the newcomers to learn the job on an individual and informal basis from senior colleagues, and through trial-and-error. Such a process would be characterized as low in contextual tactics.

Social tactics refer to social support and mentoring. The presence of a high degree of social tactics affords newcomers guidance and support from incumbents, easing them into their new roles. Social tactics constitute the phase of situated learning where senior colleagues guide newcomers and help them interpret their roles and the context (Gherardi, Nicolini, & Odella, 1998). Social tactics also provide social support through unequivocal acceptance of newcomers “as they are” by organizational insiders (Ashforth & Saks, 1996) and facilitation of adjustment to the new context. At the other extreme, low social tactics offer no role models or mentors to the newcomer. The newcomer has to discover and acquire the tacit organizational and job knowledge without any guidance. Furthermore, the organization may seek to radically alter newcomers’ perceptions of themselves by emphasizing their lack of preparation for the current role (Van Maanen & Schein, 1979). Social tactics communicate the social status accorded to newcomers in the incumbent’s eyes, thus confirming or disconfirming their sense of selfworth (Jones, 1986).

Content tactics refer to the structure of socialization. A high level of content tactics would involve a precise timetable to newcomers with respect to the duration of the socialization, when they are likely to be accepted as having the requisite knowledge and competencies for the role. Newcomers can discern the progress from one stage of socialization to the other, as they learn the content of several roles or several aspects of their target roles in a clearly laid out sequence. At the other extreme, with low content tactics, newcomers may experience heightened uncertainty because they do not have an idea of when they are likely to finish a particular stage and pass the boundary to the next step or pass on to being considered organizational insiders.

The three groups of socialization tactics serve distinct purposes. Contextual tactics serve to integrate newcomers with their cohort and provide basic training. Social tactics allow newcomers to learn the job under the tutelage of incumbents while integrating with the workgroup and developing organizational identity. Content tactics provide a structure and an index of progress for the newcomers. A meta-analysis of several studies from all over the world, including Asia, has shown that high levels of socialization tactics bear a powerful influence on newcomer adjustment through role and value clarification, and are positively related to role clarity and organizational commitment, among other outcomes (cf. Saks et al., 2007). These tactics were also found to be negatively related to role conflict and innovative role orientation. The question is whether or not women newcomers receive the same level of socializing influences through these tactics as their male counterparts.

Women and organizational socialization

Women may experience two distinct but related barriers to socialization: social exclusion and lack of access. In professions and organizations that have hitherto been male-dominated, the ideology and social context engender insider behaviors and signals that effectively preclude integration of women newcomers. Studies have shown that socializing agents (who are men) engender and encourage differentiation and boundaries between the genders (Moore, 1999; Prokos & Padavic, 2002). The boundary maintenance often extends to the informal groups. Newcomers tend to rely on each other and learn from each other in the early days after organizational entry. This collective learning is fostered by an “in the same boat” consciousness among newcomers, and promotes bonding within the cohort (Van Maanen & Schein, 1979). Women are often excluded from this informal collective. When women veer away from the traditional stereotypes and enter male-dominated professions such as seafaring and policing, they may be greeted not necessarily with hostility but with apprehension (Guo & Liang, 2012; Prokos & Padavic, 2002). The resulting social exclusion deprives women of information, learning, and networks (Lyness & Thompson, 2000; Prokos & Padavic, 2002).

Workplace expectations of gendered behavior have crystallized over several decades, and women themselves may anticipate roles consistent with these expectations (Choi, 1999; Martin & Collinson, 2002). Women, having been stereotyped as caring and nurturing, may be shunted to the aspects of work that require less masculinity in the eyes of the management (N. Fielding & J. Fielding, 1992). For instance, Guo and Liang (2012) narrate how superior officers on board Taiwanese ships avoided giving deck work to women seafarers because it involved dangerous work. Such benevolent stereotyping proves to be counterproductive because it prevents women from mastering the job.

Researchers finding similar patterns in Asia noted that stereotyping and relegation of women to token status in the workplace probably fits the prevalent cultural norm and receives sanction in Asian societies (Cho et al., 2010; Kang & Rowley, 2005). Although Asian societies significantly differ in their socio-economic and cultural profiles, there seem to be some commonalties between these societies with respect to women in the workplace. In Asian settings such as Korea, Hong Kong, Singapore and Malaysia, women workers continue to be stereotyped as torn between work and family, passive and nurturing (Lee & Tan, 1993; Lee, 2003). The patriarchal social values reinforce these stereotypes. Thus, in Southeast and Northeast Asia, the working woman is expected to conform to the traditional perceptions of her role: more sociable, less assertive, relaxed, and group-oriented. Asian women in the workplace frequently lower their career ambitions in order to meet this social expectation (Ng, Fosh, & Naylor, 2002). Therefore, inequality between the sexes might be more prevalent in the Asian setting than in the west, although no conclusive evidence is available.

Even if the initial phases of orientation and training are exclusionary, the effects could be ameliorated through the newcomer’s interactions with experienced insiders such as senior colleagues and supervisors as characterized by social tactics. Firstly, the interactions could inject a shot of much needed confidence in the anxious newcomer through social support and role modeling (Ragins & McFarlin, 1990). Secondly, interactions with these mentors help clarify tacit organizational knowledge, allow newcomers to build networks and chart career-enhancing strategies. In the case of women, however, it has been argued that social exclusion and consequent lack of access to information often persists beyond the orientation and training phases (Noe et al., 2002). Empirical evidence for these arguments is mixed.

Some studies found that women do not often have access to experienced insiders as mentors, and even when they do, these mentors are not the most powerful within the organization (Dodd-McCue & Wright, 1996; Dreher & Cox, 2000; Forret & Dougherty, 2004). Others found either weak or no gender effects on receipt of mentorship, socialization levels, career advancement, insider networking or compensation (e.g. Dreher & Ash, 1990; Turban & Dougherty, 1994). Although inconclusive, evidence suggests that same-sex mentoring relationships are more productive for the protégé than cross-gender relationships in several instances (Allen et al., 2005; Ragins & McFarlin, 1990). In settings with few women in senior positions, therefore, female newcomers may not receive the same level of psychosocial and career mentoring as men. In terms of socialization tactics, this implies that women are less likely to receive social tactics.

Inadvertent or conscious exclusion might indicate that a newcomer should not aspire to the same career path or career progression as her male counterparts. For example, assignments which are prized as fasttrack assignments often require selected newcomers to perform a series of assignments in different departments before they are promoted (Van Maanen & Schein, 1979). If such a track is exclusively available for men, then it suffices as a signal of career path for the female newcomer. This is the type of information conveyed to the newcomer through content tactics. Social exclusion by the cohort and lack of equal access to incumbents could potentially screen such opportunities and information from female newcomers. Importantly, whether or not such differences exist, women seem to perceive these barriers in socialization (Ragins, 1999), and that could potentially have deleterious effects on adjustment. In other words, the quantity and quality of socialization received might vary by gender in a systematic fashion.

H1: All else being equal, female newcomers will report receiving less of contextual, social, and content socialization tactics than male newcomers.

Gender and Socialization Outcomes

Effective socialization helps to reduce role stress for newcomers, clarifies their roles, and enables them to identify with the organization (Van Maanen & Schein, 1979). In this study, socialization outcomes of role clarity, role conflict, role orientation, and organizational commitment were assessed. Role clarity has three elements: goal clarity, process clarity, and reward clarity (Ashford & Cummings, 1985; Sawyer, 1992). Goal clarity refers to the knowledge of the goals and responsibilities that accompany the role. The role holder also needs to understand the means of attaining the goals and fulfilling the responsibilities. This knowledge is termed process clarity (Sawyer, 1992). Ashford and Cummings (1985) identified another role-related uncertainty which they called contingency uncertainty. Contingency uncertainty refers to the clarity of reward systems in the organization (Ashford & Cummings, 1985). In this study, this contingency uncertainty was labeled reward clarity. Role orientation can be custodial or innovative (Van Maanen & Schein, 1979). Custodial orientation refers to the newcomer conforming to the prescribed role description while innovative orientation refers to a proactive attempt to alter the role definition and scope.

What can be gleaned from the existing research is that the effects of socialization processes are in the same direction for men and women, provided the processes are identical in design and execution. Burke and McKeen (1994) found that participation in formal training sessions (analogous to contextual tactics) seems to benefit women as much it does men, if not more. Similarly, some studies found that a well-established mentor-protégé relationship benefits men and women equally well (Allen et al., 2005).

However, the intensity of the outcomes due to specific tactics might differ between the sexes due to differences in value orientations and learning styles. Several authors have argued that women have a more interpersonal orientation than men and are typically socialized into values reflecting a concern for others and place greater emphasis on group involvement (Anderson & Martin, 1995; Choi & Koo, 2006). Others noted that women need co-worker support and mentorship to teach them the political skills needed to succeed in the workplace (Ferris, Frink, Bhawuk, Zhou, & Gilmore, 1996). Thus, women are likely to benefit more from supportive colleagues with whom they can affiliate and exchange information. Moreover, knowledge of processes and rewards is always contextual, and this knowledge can be obtained only through interaction. Secondly, women frequently experience increased role stress, especially due to the work-family role conflict and consequently, less commitment (Davey & Arnold, 2000; Dodd-McCue & Wright, 1996). Social support from mentors and co-workers appears to alleviate role conflict more for women than men (Nelson & Quick, 1991).

Theories of learning styles (Baxter Magolda, 1998; Severiens & Ten Dam, 1998) augment this position. Women seem to focus on interpersonal and relational aspects for learning whereas men are individually focused and emphasize mastering the pattern in their learning. Women focus on learning from the teacher, seek direct feedback, discuss with others, and incorporate others’ perspectives into their learning, whereas men are more focused on structured learning and on their own perspectives (Miller & Karakowsky, 2005; Severiens & Ten Dam, 1998). These arguments indicate that social tactics are even more important for the adjustment of female newcomers. Similarly, contextual tactics which are intended to instruct the newcomer while promoting within-cohort interaction are likely to be more salient for female newcomers for role learning and integration. Paradoxically enough, women are also less likely to experience these tactics than their male counterparts due to social exclusion and lack of access to mentors.

Salminen-Karlsson (2006) pointed out that situated learning involved in social tactics is affected by the incumbents’ dispositions towards the newcomers. Female newcomers who do not experience exclusion by mentors or the pressure to conform to gender stereotypes are more likely to benefit from social tactics. Supportive supervisors and peers can also have the effect of empowering the newcomer to redefine and expand her role (Kirchmeyer, 1995). Therefore, it is hypothesized that social and contextual tactics will be more instrumental for female newcomers in attaining role clarity and reducing role conflict while promoting an innovative role orientation and organizational commitment.

In contrast, men seem to be oriented towards impersonal and structured learning as reflected in content tactics (Severiens & Ten Dam, 1998). Thus, content tactics should be more salient for male newcomers in terms of role learning and role orientation. This does not negate the importance of other tactics for male newcomers; nor does it assert that social and contextual tactics are significant only in the case of female newcomers. Rather, the position is that the effect of content group of tactics on role outcomes and organizational commitment are likely to be more accentuated in the case of men while those of contextual and social tactics are likely be accentuated in the case of women.

H2: All else being equal, social and contextual tactics will be more strongly and positively related to process clarity, goal clarity, reward clarity, innovative role orientation, and organizational commitment for female newcomers. Social and contextual tactics will be more strongly and negatively related to role conflict for female newcomers.

H3: All else being equal, content tactics will be more strongly and positively related to process clarity, goal clarity, reward clarity, innovative role orientation, and organizational commitment for male newcomers. Content tactics will be more strongly and negatively related to role conflict for male newcomers.

Method

Data was collected in three waves of surveys over a period of six months. The initial respondent pool came from 512 business undergraduates from a Southeast Asian university. The first questionnaire was mailed to the subjects soon after their graduation. This questionnaire sought information on the respondent’s demographic information, and job profile if s/he had had an offer. The first phase resulted in 220 completed questionnaires (43%). The second wave of questionnaires was sent to these respondents three months later when most respondents would have completed their first few weeks in a full time job. This was to allow for the local variation of a two- month gap between graduation and placement. The second questionnaire collected information on the socialization tactics used in the organization. This wave yielded 162 usable responses (73.6% of first wave). The third wave of questionnaires was sent an additional two months later. This questionnaire inquired about the socialization outcomes. After the third wave, a total of 149 usable responses were obtained, giving an overall response rate of 29.1% from the original sample of 512. The surveys were administered in English. All graduates are proficient in English, which is the language of instruction and student interaction in the university. The six-month period of survey administration served to capture newcomer experiences and socialization outcomes during the first eight-nine weeks of employment, which are most critical for socialization (Saks et al., 2007).

Measures

Independent variables. Socialization tactics were measured with a 7-point Likert scale using 18 items adapted from the 30-item instrument developed by Jones (1986). Each tactic group was measured with six items. Items used in this study are given in the appendix. The items were subjected to a confirmatory factor analysis for a 3-factor model using AMOS 18. The model showed an acceptable fit (x2(132) = 188.2, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.90, IFI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.05[p > 0.1]). Subsequently, each group of tactics was computed by averaging the items of the two tactics in the group. Gender was coded as “0” for women and “1” for men.

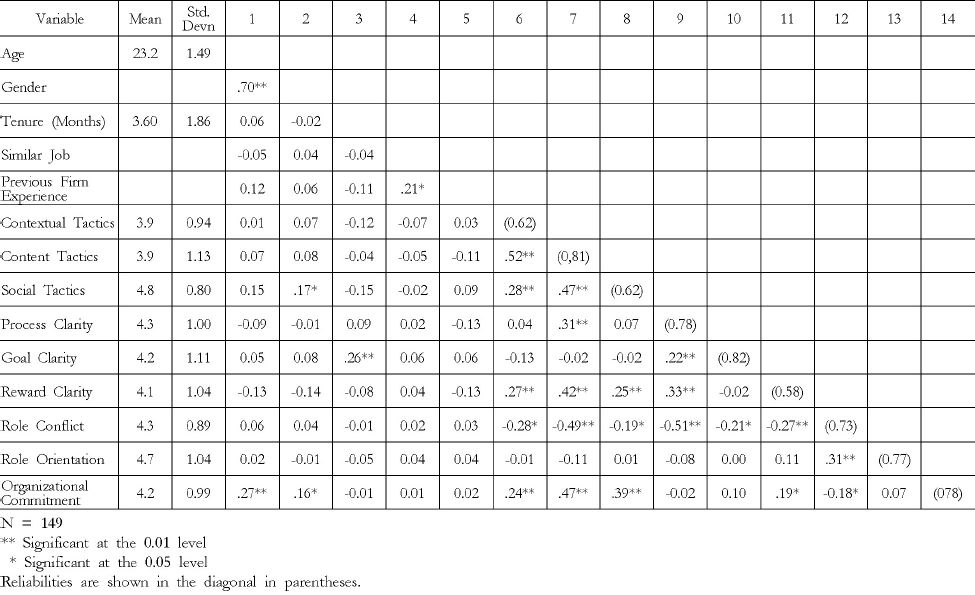

Dependent Variables. Six outcomes were assessed in this study, and all variables were measured using a 7-point Likert scale. Goal clarity was measured with four items from Sawyer’s validated scale (1992). The fifth item in Sawyer’s measure referred to reward clarity, which was measured as a separate construct in this study. Process clarity was measured with Sawyer’s (1992) five-item scale, and reward clarity was measured with the five-item contingency uncertainty scale from Ashford and Cummings (1985). Role orientation was measured with four items from Allen and Meyer (1990). Role conflict was measured with six items from the Rizzo, House and Lirtzman (1970) scale. Organizational commitment was measured with the ten-item version of OCQ (Porter, Steers, Mowday, & Boulian, 1974). The reliabilities, variable inter-correlations and descriptive statistics of the tactics and all other variables are shown in table 1. Reliability for the reward clarity measure was low (0.58).

Control variables. The analysis controlled for the effects of respondent age, organizational tenure in months at the time of wave 3, previous work experience in the same firm, and similarity of any previous jobs to the current job. Job similarity and previous experience in the same organization were coded as dummy variables with the values of “0” and “1”.

Data Analysis and Results

One hundred (100) female and 49 male graduates participated in this study. The mean age of the sample is 23.2 years, with an average tenure of 3.6 months at time 3. The higher proportion of female participants somewhat reflected the composition of the original sample. The respondents are from diverse occupations, such as accountancy, auditing, banking, and manufacturing industries. Twenty-four respondents reported prior experience in a similar job and twelve were previously employed by the current organization.

Hypothesis 1 predicted that female newcomers would report receiving less institutionalized tactics than their male counterparts. The male and female proportions of the current sample are significantly different (49 vs. 100). When sample sizes are significantly different, assumptions of equality of variances might be severely violated, rendering comparison of means invalid. A Levene test for homogeneity of variance indicated that the variances of tactics between the groups are not significantly different (p > 0.1). The procedure also tests for difference in means between groups without assuming equality of variances. In addition, the Welch statistic was obtained using the ANOVA procedure to further check the results. Welch’s ‘t’ corrects for sample size differentials and allows comparison of means when the group sizes are significantly different (Ott, 1984). The results (table 2) show that only social tactics are significantly different between the two groups (M male = 5.07, M female = 4.77, t’(1,86.98) (Welch) = 4.232, p < 0.04). Contextual and content tactics do not significantly differ between the two groups. This lends partial support to hypothesis 1.

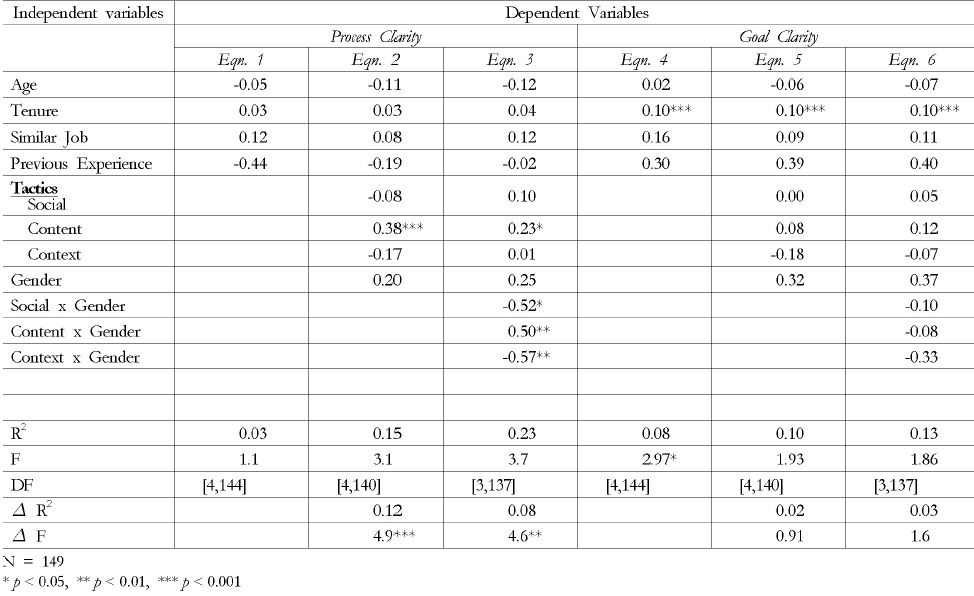

Hypotheses 2 and 3 posited that gender would moderate the relationship between tactics and socialization outcomes. To test these hypotheses, hierarchical moderated regression was used (Cohen, Cohen, West, &' Aiken, 2003). Interaction terms for gender with the three tactics variables were computed after centering the tactics variables. In step 1, control variables were entered. In step 2, independent variables of tactics and gender were entered. In step 3, interaction terms were introduced. The results are shown in tables 3, 4, and 5.

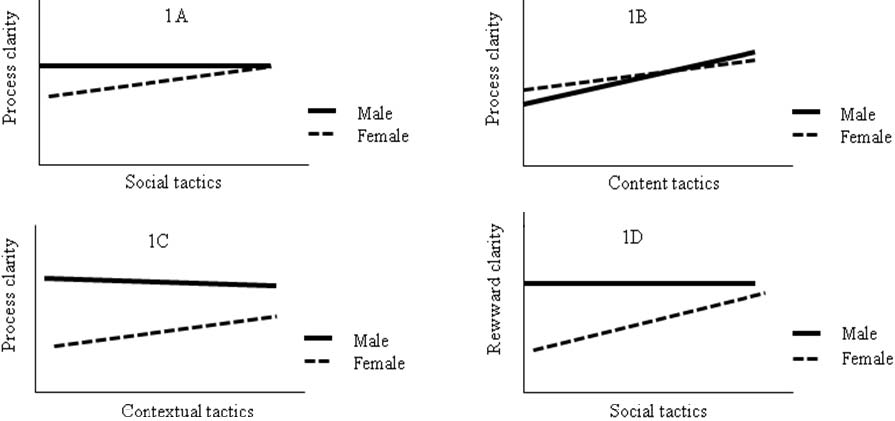

Process clarity was positively related to content tactics (Equation 2, table 3, B = 0.38, p < 0.001), with a significant overall equation. Equation 3 of table 3 shows that all three interaction terms for tactics and gender are significant. The interaction term for content tactics and gender is positively related to process clarity (B = 0.50) while the interaction terms of gender with social (B = -0.52,) and contextual (B = -0.57) are negative. Given that masculine gender was coded as “1” and feminine as “0”, the results indicate that content tactics are more salient for men to attain process clarity whereas social and contextual tactics are more helpful for female newcomers for the same purpose. Equations 4, 5 and 6 of table 3 show the results for goal clarity. No significant main or interaction effects were found for goal clarity.

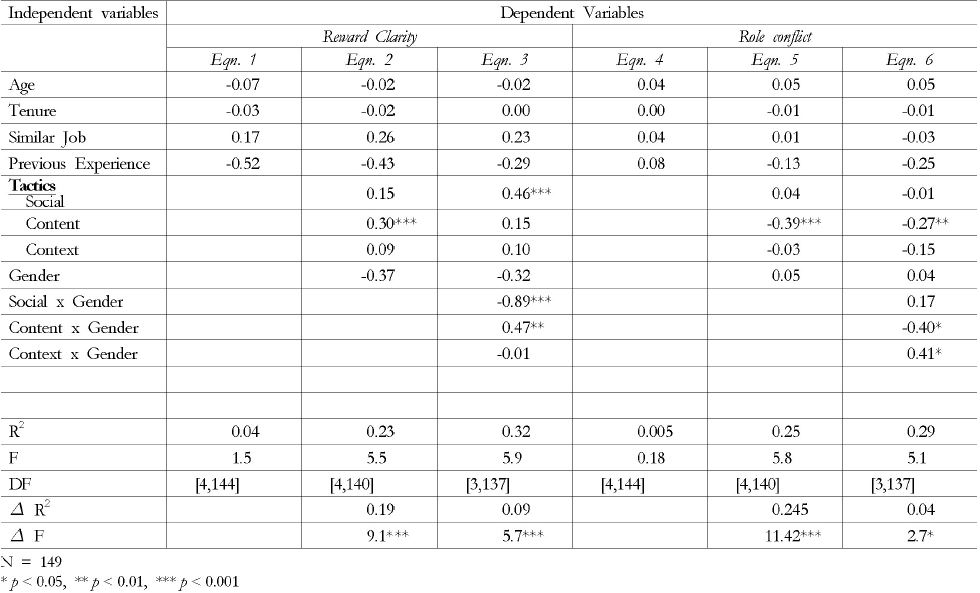

In the case of reward clarity (table 4), content tactics yield the only significant main effect. The interactions of gender with social and content tactics are significant. The regression coefficient for gender and social tactics interaction term is negative (B = -0.89), indicating that female newcomers found social tactics more useful for understanding the organization’s reward systems and processes. In the same vein, the interaction term of content tactics and gender is positive (B = 0.47) as expected; male newcomers appear to rely more than female newcomers on the structured learning provided by the organization to decipher its reward structures. There is no moderator effect for gender and contextual tactics on reward clarity.

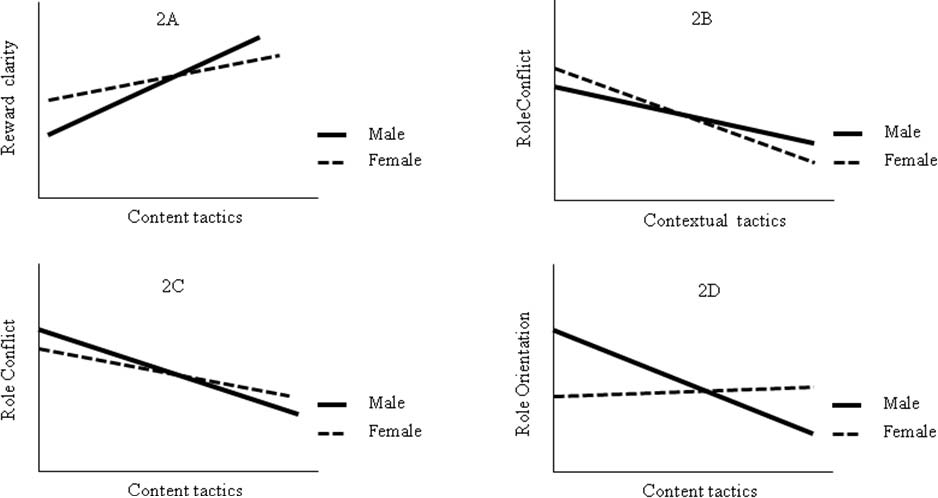

Role conflict was significantly related to content tactics (equation 5, table 4, B = -0.39, p < 0.001) indicating that content tactics are associated with reduced role conflict. The equation for the interaction step is significant (equation 6, table 4, ΔR2 = 0.04, ΔF (3,137) = 2.7, p < 0.05). Contextual tactics are positively moderated by gender (B = 0.41) whereas content tactics are negatively moderated (B = -0.40). The result implies that male newcomers found content tactics more useful in reducing role conflict whereas contextual tactics seem to have been instrumental in allowing female newcomers to cope with role conflict. It was expected that social tactics would have a significant bearing on role conflict; however, the results here negate the expectation.

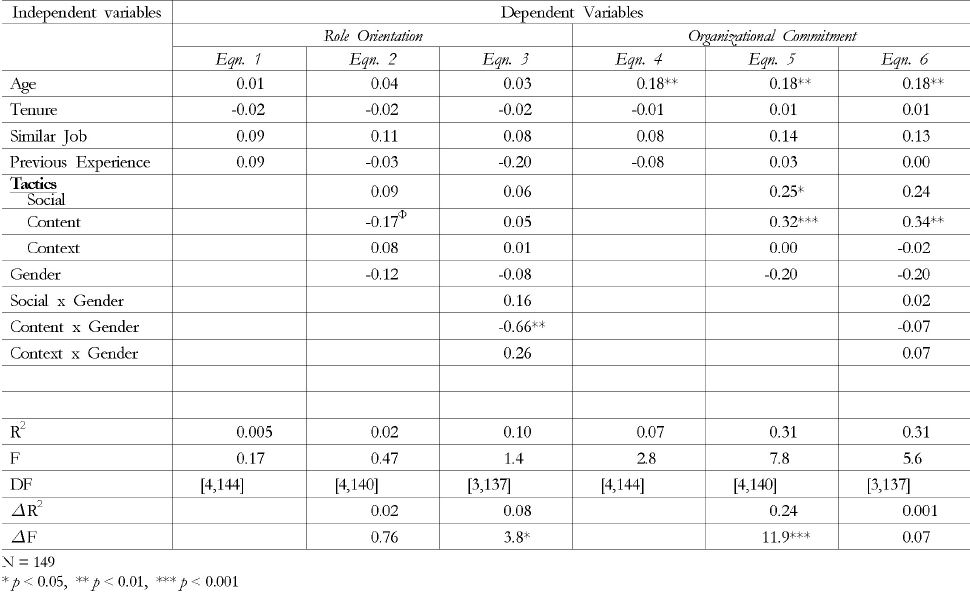

Table 5 shows the results for the last two dependent variables of role orientation and organizational commitment. Role orientation is not significantly related to any of the independent variables (equation 2, table 5). The interaction step, however, is significant (equation 3, table 5, Δ R2 = 0.08, ΔF (3,137) = 3.8, p < 0.01). Surprisingly, content tactics are negatively moderated by gender (B = -0.66, p < 0.01), suggesting that content tactics are instrumental in promoting an innovative role orientation among female newcomers.

To verify this as well as other results, all significant interaction effects were plotted as shown in figures 1 and 2. Figure 2D shows the plot for content tactics against role orientation by gender. The plot reveals that the interaction effect is spurious in that content tactics appear to have negligible effect on the role orientation of women and in fact, increasing content tactics induce a custodial orientation among men. This negative effect was reflected in the equation above, and consistent with earlier findings that institutionalized tactics induce a custodial role orientation (conformity). The remaining plots indicate that the rest of the significant interactions are genuine.

Equations 4, 5 and 6 of table 5 show the results for organizational commitment. Commitment is significantly related to social and content tactics. However, no significant interaction was found. The results provide partial support to hypotheses 2 and 3.

Summarizing the results, female newcomers reported receiving less social tactics than male newcomers. With regard to socialization outcomes, gender negatively moderated the effects of social tactics on process clarity and reward clarity, indicating that female newcomers tend to draw more from social tactics than male newcomers with respect to role learning. Gender also negatively moderated the effects of contextual tactics on process clarity and positively, on role conflict. This result suggests that female newcomers rely on training and orientation to learn to manage role conflict, and increase their understanding of the process. Gender positively moderated the effects of content tactics on process clarity and reward clarity, and negatively on role conflict. This is the obverse of the result for social tactics in that male newcomers seem to rely more on structured learning processes to learn and manage their roles. There are no appreciable main and interaction effects on goal clarity and role orientation. Organizational commitment is related to social and content tactics but there are no significant interactions.

Discussion

Previous research on organizational socialization has assumed that men and women respond to various tactics in a uniform fashion. This study has investigated the differentials in the administration and impact of organizational socialization tactics on male and female organizational newcomers. The study is also the first to investigate the impact of gender on socialization tactics and outcomes in an Asian country where an increasing number of women are entering the workforce in professions hitherto dominated by men.

Results indicate that women newcomers receive less social support and mentoring than men do across a spectrum of organizations. More precisely, women in this sample seem to have fewer opportunities to be “one of the boys” in the workplace. Importantly, there seem to be no structural barriers for women in terms of socialization at organizational entry. Women and men reported similar patterns of training and opportunity. This is evident in the lack of a significant difference in contextual and content tactics for the two genders.

The results also indicate that women and men respond to the various tactics in different ways. Role learning is enhanced for women through social and contextual tactics whereas male newcomers seem to draw similar benefits through content tactics. While social tactics seem to have the most salutary effect on the adjustment of any newcomer (Simosi, 2010), they seem to be salient for socialization of female newcomers. The results reinforce extant findings on mentoring, networks, and gender.

Mentorship research has long noted that a supportive and inclusive environment that provides women with access to mentors is likely to result in better performance, career growth and less role stress (Noe et al., 2002). When organizational insiders proactively offer social support and mentoring, women may learn their roles more quickly and experience a superior sense of fit.

It might come as no surprise that a Southeast Asian culture known to be steeped in tradition should show a gender bias particularly with reference to social tactics. A word of caution, however, may be necessary. History and social conditions including primary socialization across strata vastly vary across Asian societies. Women’s advancement in business in many countries is shaped by the legacy of this history. For instance, women in China seem to face fewer barriers to entrepreneurial activity than in many other countries (Hussain, Scott, Harrison, & Millman, 2010). On the other hand, advanced societies such as Singapore and Korea have reported continued discrimination against and stereotyping of women in the workplace (Kang & Rowley, 2005; Lee, 2003; Lee & Tan, 1993).

In Singapore, the government has been proactive in promoting women’s education and employment through a slew of measures involving legislation and infrastructural support (Tan, 2009). However, there are no legal measures against gender discrimination; nor are there rules to enforce flexible work systems. This has generated conflicting signals for aspiring women in a society steeped in Confucian tradition. Popular discourse reinforces tradition by highlighting the conflicting roles of a woman (Lee & Tan, 1993). Lee and Tan (1993) noted that a female manager’s success in Singapore depends on a support system that includes a male mentor at the workplace, and a supportive spouse and domestic help at home. The net result is that gender is often used as one of the criteria for selection and promotion (Tan, 2009). Nevertheless, Tan (2009) notes that a significant number of women managers in Singapore have reached the top of their organizations. This may be due in part to a realization that, with declining birth rates and increasing economic pressures, gender discrimination is detrimental to the organization.

The Korean case provides a contrast. Governments have instituted several measures, including affirmative action to correct gender bias (Cho et al., 2010). Tradition and culture, however, seem to have a dampening effect on these measures. As of 2012, Korea continues to have one of the lowest workforce participation rates for university-educated women among OECD countries (OECD, 2012). Moreover, the gender wage gap is the highest in Korea among OECD countries (OECD, 2012). Thus, in Singapore, markets rather than the government appear to have brought about a modicum of gender equality. In Korea, no amount of structural reform is able to mitigate the effects of traditional practices. These differences may arise due to the specific location of historical, cultural, and social factors in each society. Thus a more fine-grained understanding of women in the Asian workplace is warranted.

Barriers to socialization may not always be consciously erected by the dominant group. These might be deeply embedded in societal and organizational cultures. Ingrained habits of culture are notoriously hard to change through exhortations or policy proclamations. For this reason, organizations need to ensure, by design, that female newcomers have equal access to insiders. Although they concede that informal mentorships and self-selection are more effective vehicles for socialization, McManus and Russell (1997) maintained that mentoring should be seen as an in-role behavior by the incumbents. Since issues of interpersonal comfort and biases arising from similarity seem to close the door on female newcomers in organizations, formalization of mentoring functions is imperative.

In organizations and professions where women enjoy relative numerical strength, socialization practices might have been adapted to accommodate women over time. However, the view that sheer numbers could obviate archaic stereotypes and male in-groupism may be too optimistic (Eagly & Carli, 2007). For instance, the field of business administration has witnessed a significant increase in the number of women graduates who go on to actively participate in the workforce (Wilton, 2007). Occupations such as nursing and social work have a female majority; yet in all these three fields, relatively fewer women have risen to the top (Eagly & Carli, 2007).

The sample for this study came from the field of business administration where women are increasing in numbers and the sample composition attests to the possibility. Women in this sample did not report any differential treatment with respect to training, integration with the cohort or the progression towards the target role, thus ruling out any intentional bias. Thus, exclusionary practices may not be a foregone conclusion. Numerical strength might, to some extent, obviate discriminatory practices in training and processing at the point of organizational entry. Yet, results also indicate that latitude exists for gender differentiation when it comes to the interpersonal and interactional aspect of socialization.

The question then remains whether such differentiation could begin right at the orientation and training aspects of socialization, and continue at every stage of the socialization process, if women were fewer in numbers. In other words, if there are differences in the amount of contextual and content tactics received by women, what will be the compounded effect on their adjustment and commitment? While this study has failed to provide an answer to the question, it has attempted to lay the ground for a more comprehensive examination of socialization with reference to gender. One could argue that initial exclusion creates a vicious circle leading to less access to seniors and supervisors, a question worthy of future research.

The study has several limitations. There are several assumptions embedded within the arguments and analysis here. The study does not reveal the process and remains a snapshot of tactics across several organizations. In concluding that certain tactics are salient for men and women, one runs the risk of assuming that events such as social exclusion had taken place or that training was uniformly administered without ever having witnessed the process. Similarly, there is an embedded assumption that women mentors are scarce in the sample, a premise drawn from theory. Therefore, such cross-sectional research should be complemented by ethnographic investigations that present a rich detail of socialization practices. The sample in this study is limited to one field and one location; therefore, the results cannot be generalized. More research across organizations, professions, and cultures is needed before placing faith in the inferences here. Nonetheless, the study marks a small beginning for future research on the relationship between gender, socialization, and career progress in the Asian context. Several questions remain unanswered in the literature, and the arguments in this paper hopefully present a fruitful avenue for answering some of these questions.

References

-

Allen, B. J., (1996), Feminist standpoint theory: A black woman’s (re)view of organizational

socialization, Communication Studies, 47, p257-271.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/10510979609368482]

-

Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P., (1990), Organizational socialization tactics: A longitudinal

analysis of links to newcomers’ commitment and role orientation, Academy of Management Journal, 33, p847-858.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/256294]

-

Allen, T. D., & Eby, L. T., (2004), Factors related to mentor reports of mentoring

functions provided: Gender and relational characteristics, Sex Roles, 50, p129-139.

[https://doi.org/10.1023/B:SERS.0000011078.48570.25]

-

Allen, T. D., Day, R., & Lentz, E., (2005), The role of interpersonal comfort in

mentoring relationships, Journal of Career Development, 31, p155-169.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10871-004-2224-3]

-

Alvesson, M., & Billing, Y. D., (1992), Gender and organization: Towards a differentiated

understanding, Organization Studies, 13, p73-103.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/017084069201300107]

-

Anderson, C. M., & Martin, M. M., (1995), Why employees speak to coworkers

and bosses: Motives, gender, and organizational satisfaction, Journal of Business

Communication, 32, p249-265.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/002194369503200303]

-

Ashford, S. J., & Cummings, L. L., (1985), Proactive feedback seeking: The instrumental

use of the information environment, Journal of Occupational Psychology, 58, p67.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1985.tb00181.x]

-

Ashforth, B. E., & Saks, A. M., (1996), Socialization tactics: Longitudinal effects

on newcomer adjustment, Academy of Management Journal, 39, p149-178.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/256634]

-

Bailyn, L., (2003), Academic careers and gender equity: Lessons learned from MIT, Gender, Work & Organization, 10, p137-153.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0432.00008]

- Baxter Magolda, M. B., (1998), Learning and gender: Complexity and possibility, Higher Education, 35, p351-355.

- Bernstein, B. L., & Russo, N. F., (2008), Explaining too few women in STEM careers: A psychosocial perspective. In M. A. Paludi (Ed.), The psychology of women at work: Challenges and solutions for our female workforce: Vol. 2. Obstacles and the Identity Juggle, Praeger Publishers, Westport, CT, p1-34.

-

Burke, R. J., & McKeen, C. A., (1994), Training and development activities and

career success of managerial and professional women, Journal of Management

Development, 13, p53-63.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/02621719410058383]

-

Cable, D. M., & Parsons, C. K., (2001), Socialization tactics and person-organization

fit, Personnel Psychology, 54, p1-23.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2001.tb00083.x]

-

Cho, J., Kwon, T., & Ahn, J., (2010), Half success, half failure in Korean affirmative

action: An empirical evaluation on corporate progress, Women’s Studies International Forum, 33, p264-273.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2010.02.020]

- Choi, E., (1999), Gender roles and gender identity across different age groups, Asian Women, 9, p221-241.

- Choi, M. C., & Koo, H., (2006), Sex and job values in comparative perspective, Asian Women, 22, p81-106.

- Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S., & Aiken, L., (2003), Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ.

-

Davey, R. M., & Arnold, J., (2000), A multi-method study of accounts of personal

change by graduates starting work: Self-ratings, categories and women’s

discourses, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 73, p461-486.

[https://doi.org/10.1348/096317900167164]

-

Dodd-McCue, D., & Wright, G. B., (1996), Men, women, and attitudinal commitment:

The effects of workplace experiences and socialization, Human Relations, 49, p1065-1091.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679604900803]

-

Dreher, G. F., & Cox, T. H., (2000), Labor market mobility and cash compensation:

The moderating effects of race and gender, Academy of Management Journal, 42, p890-900.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/1556417]

-

Dreher, G. F., & Ash, R. A., (1990), A comparative study of mentoring among

men and women in managerial, professional, and technical positions, Journal

of Applied Psychology, 75, p539-546.

[https://doi.org/10.1037%2F/0021-9010.75.5.539]

-

Dryburgh, H., (1999), Work hard, play hard - women and professionalization in

engineering - adapting to the culture, Gender & Society, 13, p664-682.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/089124399013005006]

- Eagly, A. H., & Carli, L. L., (2007), Through the labyrinth: The truth about how women become leaders, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

-

Ferris, G. R., Frink, D. D., Bhawuk, D. P. S., Zhou, J., & Gilmore, D. C., (1996), Reactions of diverse groups to politics in the workplace, Journal of Management, 22, p23-44.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639602200102]

-

Fielding, N., & Fielding, J., (1992), A comparative minority; Female recruitment

to a British constabulary, Policing and Society, 2, p205-218.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.1992.9964642]

-

Forret, M. L., & Dougherty, T. W., (2004), Networking behaviors and career outcomes:

Differences for men and women?, Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25, p419-437.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/job.253]

-

Gherardi, S., Nicolini, D., & Odella, F., (1998), Toward a social understanding of

how people learn in organizations: The notion of situated curriculum, Journal

of Management Learning, 3, p273-297.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507698293002]

-

Gunkel, M., Lusk, E. J., Wolff, B., & Li, F., (2007), Gender-specific effects at

work: An empirical study of four countries, Gender, Work & Organization, 14, p56-79.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2007.00332.x]

-

Guo, J. L., & Liang, G. S., (2012), Sailing into rough seas: Taiwan’s women seafarers’

career development struggle, Women’s Studies International Forum, 35, p194-202.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2012.03.016]

-

Hussain, J., Scott, J., Harrison, R., & Millman, C., (2010), Enter the dragoness:

Firm growth, finance, and gender in China, Gender in Management, 25, p137-156.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/17542411011026302]

-

Ibarra, H., (1993), Personal networks of women and minorities in management: A

conceptual framework, Academy of Management Review, 18, p56-87.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/258823]

-

Jones, G., (1986), Socialization tactics, self-efficacy and newcomers’ adjustments to organizations, 29, p262-279.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/256188]

-

Kang, H.-R., & Rowley, C., (2005), Women in management in South Korea:

Advancement or retrenchment?, Asia Pacific Business Review, 11, p213-231.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/1360238042000291171]

- Kanter, R. M., (1977), Men and women of the corporation, Basic Books, New York.

-

King, E. B., Hebl, M. R., George, J. M., & Matusik, S. F., (2010), Understanding

tokenism: Antecedents and consequences of a psychological climate of gender

inequity, Journal of Management, 36, p482-510.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308328508]

-

Kirchmeyer, C., (1995), Demographic similarity to the work group: A longitudinal

study of managers at the early career stage, Journal of Organizational Behavior, 16, p67-83.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030160109]

- Küskü, F., Özbilgin, M., & Özkale, L., (2007), Against the tide: Gendered prejudice and disadvantage in engineering, Gender, Work & Organization, 14, p109-129.

- Lee, C. W., (2003), A study of Singapore’s English channel television commercials and sex-role stereotypes, Asian Journal of Women’s Studies, 9, p78-100.

-

Lee, S. K. J., & Tan, H. H., (1993), Rhetorical vision of men and women managers

in Singapore, Human Relations, 46, p527-542.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679304600406]

-

Louis, M., (1980), Surprise and sense-making what newcomers experience in entering

unfamiliar organizational settings, Administrative Science Quarterly, 25, p226-251.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/2392453]

-

Lyness, K. S., & Thompson, D. E., (2000), Climbing the corporate ladder: Do female

and male executives follow the same route?, Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, p86-101.

[https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.85.1.86]

-

Martin, P. Y., & Collinson, D., (2002), Over the pond and across the water:

Developing the field of gendered organizations, Gender, Work & Organization, 9, p244-265.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0432.00159]

-

McManus, S. E., & Russell, J. E. A., (1997), New directions for mentoring research:

An examination of related constructs, Journal of Vocational Behavior, 51, p145-161.

[https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1997.1597]

-

Miller, D. L., & Karakowsky, L., (2005), Gender influences as an impediment to

knowledge sharing: When men and women fail to seek peer feedback, Journal

of Psychology, 139, p101-118.

[https://doi.org/10.3200/JRLP.139.2.101-118]

-

Moore, D., (1999), Gender traits and identities in a “masculine” organization: The

Israeli police force, Journal of Social Psychology, 139, p49-68.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00224549909598361]

-

Nelson, D. L., & Quick, J. C., (1991), Social support and newcomer adjustment

in organizations: Attachment theory at work, Journal of Organizational Behavior, 12, p543-554.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030120607]

-

Ng, C. W., Fosh, P., & Naylor, D., (2002), Work-family conflict for employees

in an East Asian airline: Impact on career and relationship to gender, Economic

and Industrial Democracy, 23, p67-105.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X02231005]

-

Noe, R. A., Greenberger, D. B., & Wang, S., (2002), Mentoring: What we know

and where we might go. In G. R. Ferris & J. J. Martocchio (Eds.), Research

in personnel and human resources management, Elsevier Science, New York, 21, p129-173.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-7301(02)21003-8]

-

OECD, (2012), Closing the gender gap: Act now.

[https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264179370-en]

- Ott, L., (1984), An introduction to statistical methods and data analysis, Duxbury Press, Boston, MA.

-

Porter, L., Steers, R., Mowday, R., & Boulian, P., (1974), Organizational commitment,

job satisfaction, and turnover amongst psychiatric technicians, Journal of

Applied Psychology, 59, p603-609.

[https://doi.org/10.1037/h0037335]

-

Prokos, A., & Padavic, I., (2002), There oughtta be a law against bitches:

Masculinity lessons in police academy training, Gender, Work & Organization, 9, p439-459.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0432.00168]

-

Ragins, B. R., (1999), Gender and mentoring relationships: A review and research

agenda for the next decade. In G.N.Powell (Ed.), Handbook of gender and work, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, p347-370.

[https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452231365.n18]

-

Ragins, B. R., & McFarlin, D. B., (1990), Perceptions of mentor roles in cross-gender

mentoring relationships, Journal of Vocational Behavior, 37, p321-339.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(90)90048-7]

-

Rizzo, J., House, J., & Lirtzman, S., (1970), Role conflict and ambiguity in complex

organizations, Administrative Science Quarterly, 15, p150-163.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/2391486]

- Rutherford, S., (2011), Women’s work, men’s cultures: Overcoming resistance and changing organizational cultures, Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

-

Saks, A., Uggerslev, K., & Fassina, N., (2007), Socialization tactics and newcomer

adjustment: A meta-analytic review and test of a model, Journal of Vocational

Behavior, 70, p413-446.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2006.12.004]

-

Salminen-Karlsson, M., (2006), Situating gender in situated learning, Scandinavian Journal of Management, 22, p31-48.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2005.05.005]

-

Sawyer, J. E., (1992), Goal and process clarity: Specification of multiple constructs

of role ambiguity and a structural equation model of their antecedents and

consequences, Journal of Applied Psychology, 77, p130-142.

[https://doi.org/10.1037%2F/0021-9010.77.2.130]

- Severiens, S., & Ten Dam, G., (1998), Gender and learning: Comparing two theories, Higher Education, 35, p329-350.

-

Simosi, M., (2010), The role of social socialization tactics in the relationship between

socialization content and newcomers’ affective commitment, Journal of

Managerial Psychology, 25, p301-327.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/02683941011023758]

- Tan, H. H., (2009), The changing face of women managers in Singapore. In C. Rowley & V. Yukongdi (Eds.), The changing face of women managers in Asia, Routledge, London, p123-147.

-

Turban, D. B., Dougherty, T. W., & Lee, F. K., (2002), Gender, race, and perceived

similarity effects in developmental relationships: The moderating role

of relationship duration, Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61, p240-262.

[https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1855]

- Turban, D. B., & Dougherty, T. W., (1994), Role of protégé personality in receipt of mentoring and career success, Academy of Management Journal, 37, p688-702.

- Van Maanen, J., & Schein, E. H., (1979), Toward a theory of organizational socialization. In L. L. Cummings & B. Staw (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior, JAI Press, Greenwich, CT, 1, p209-264.

-

Wilton, N., (2007), Does a management degree do the business for women in the

graduate labour market?, Higher Education Quarterly, 61, p520-538.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2273.2007.00370.x]