Intervening in the Work-Family Interface

This study used both quantitative and qualitative data to illuminate structural constraints faced by mothers and their strategies used to manage work and childcare in low-income communities in Hong Kong, China. The data were drawn from a survey (N = 1,429) of mothers living in five communities. From these data, focus was on a subset (N = 764) of data covering two low-income communities, Tin Shui Wai and Sham Shui Po. Eventually a sample of this subset (N = 285) also participated in individual in-depth interviews. Results illustrate differences between mothers in their 30s and 40s in the decision on managing dual pressures of childcare and limited income. Accordingly, younger mothers were fully concerned with childcare, as their children were younger. As such, they put the idea of employment aside even though they faced financial hardship. In contrast, the older mothers suffered more from work-family conflict, as they more likely engaged in employment. Easing younger mothers’ childcare and older mothers’ work-family interplay is therefore a reasonable concern for public support for the mothers.

Keywords:

Work-family balance, life-course, low-income community, mothers, Hong Kong, ChinaIntroduction

Demands on mothers who have to juggle work and family responsibilities have prompted many countries to restructure their welfare systems, though not necessarily successfully. Such restructuring often involves the initiative of a “farewell to maternalism,” that is, to augment public support for mothers’ domestic care-giving role (Mahon, 2005). For some, this “farewell” may mean the withdrawal of support for mother-caregivers, especially in the form of the shift from “welfare to workfare” for lone parents. Yet it also involves the prescription of “reconciliation of family and work” policies designed to strengthen family resources by promoting mothers as wage earners, providing affordable and good quality childcare services, and tax and other allowances for childbearing families (e.g., school vouchers).

Many studies also reveal the ways in which workplace policy and family practices compound conflicts between work and family roles (e.g., Asthana & Halliday, 2006; Pitt-Catsouphes, Kossek, & Sweet, 2005). Such conflicts compromise the benefit of employment to low-income mothers, when their own childcare suffers (London, Scott, & Hunter, 2004). Evidently, work-life balance policies have recently shifted the narrow focus on work and family to a broadened concern that takes into account all work, family, personal and neighborhood commitments (Russell & Bourke, 1999). The concept of the family-friendly neighborhood is important as it can theoretically advance our understanding of processes by which the neighborhood facilitates work and family functioning.

To date, most studies of the work-family dilemma have primarily focused on homogenous middle-class or affluent families consisting of dual- employed couples (Kelly, 1988; Westman & Piotrkowski, 1999; Bruening & Dixon, 2008; Becker & Moen, 1999). Smith (2002, p. 54) has rightly remarked that such a research predilection fails to recognize that the context of poor women’s life “is very different than that of middle- class women and one cannot assume that balancing work and family will be the same for these two populations” (see also Collins, 1994; Oliker, 1995). That said, however, a small number of scholars look at role preference within mothers in low-income or migrant families (Jackson, 1993; Gyamfi, Brooks-Gunn, & Jackson, 2001; Smith, 2002; Hyman, Guruge, & Mason, 2008; Wall & São José, 2004; Park, 2008). These studies, together with a number of neighborhood studies, have shown that low-income families are more dependent than high-income families on their neighborhoods for resources (e.g., Sampson, Morenoff, & Gannon-Rowley, 2002; Wilson, 1997). Furthermore, low-income mothers are likely to be disadvantaged in terms of persistent poverty and unemployment (Julkunen, 2002) or by only obtaining unstable, unrewarding employment (Kjeldstad & Ronsen, 2004; Cancian, Haveman, & Meyer, 2002; Dahl, 2003; Kalil & Ziol-Guest, 2005). Such employment does not appear to offset the mother’s loss in or worry about childcare (London et al., 2004).

Implicated in this corpus of research is that the self-support network of a family can easily break down due to economic hardships, marital difficulties, and stressors associated with multiple roles in low-income neighborhoods (Brewster & Padavic, 2002; Rodgers & Jones, 1999). Against this background, the present study endeavors to inform the formulation of family-friendly policies and service options to facilitate mothers’ balancing work and family life in low-income neighborhoods.

The present study adheres to a life-course perspective, which recognizes that families are susceptible to different resources at varying stages of the life course (Elder, 1999; Swisher, Sweet, & Moen, 2004). Moen and Yu (2000) point out that “families have always devised various decisions to deal with the inevitable exigencies that occur in life.” (p. 291). The life-course perspective focuses on the interlocking careers of husbands and wives (Bielby & Bielby, 1992; Moen & Sweet, 2004). It is also concerned with the ebbs and flows of the needs of individuals as their biographies unfold across varying life stages, notably including schooling, employment, marriage, and parenthood. Meanwhile, it proposes the importance of choices that individuals make within the confines of scripted roles and socially allocated opportunities (Moen & Sweet, 2004; Shanahan, Elder, & Miech, 1997). The perspective is increasingly prominent in policy research. For example, Stier, Lewin- Epstein, and Braun (2001) argue that family-supportive policies are closely related to women’s employment patterns along their life cycles, which are in turn related to important family events, in particular, to the presence and age of children (see also Roy, 2008). Other policy research takes into consideration the complicated, multiple temporal contexts in which an actor acquires study, work, and family roles in the life cycle, as well as the attendant shifting risk patterns, in discussions on youth, health care and employment policies (Burton & Snyder, 1998; Schoon & Bynner, 2003; Asthana & Halliday, 2006).

Specific to the present study is to examine the mothers’ decision in their transition from their 30s to 40s to see how often they shoulder the uneven burden of childcare and household responsibilities in the family during this transition (Mattingly & Bianchi, 2003; Moen & Sweet, 2003). Several studies have shown that their decision relevant to life courses are especially critical when several demanding and competing roles “pile up,” for instance, being a mother of young children and being an employee (e.g., Sweet, Swisher, & Moen, 2005). In such instances, families may employ life-course decisions that involve a manipulation of timing and sequencing of life transitions (e.g., decisions about when to have another child, or take a fulltime job), and the duration in role engagements (e.g., decisions about how long a mother should remain in a time-demanding but better-paid job). The decisions represent attempts to bring these work and family spheres into balance (Sweet et al., 2005, p. 597; Stier et al., 2001; Yeandle, 1996). Drawing upon interviews with mothers reveals their expectations of how neighborhoods might facilitate the management of work and family demands.

Social and Policy Contexts of Mothers Living in Poverty

Hong Kong counts as an affluent metropolis virtually by all international standards. The city is the world’s third largest financial center, the fifteenth richest entity in terms of GDP per capita (US$42,700 in 2009), and, according to the statistics provided by the Hong Kong government, the seventh wealthiest government in terms of foreign exchange reserves (US$258.2 billion by the end of February 2010) (“Foreign exchange,” 2010). Hong Kong is also a socially stable city with a high quality of living and is one of the world’s least corrupt regions (Sing, 2006). The latest Mercer’s Quality of Living survey indicates that Hong Kong ranks the eighth out of 215 cities in the world, suggesting that the population enjoys a relatively stable social life with few health and climatic concerns (Estes, 2002). In addition, the people of Hong Kong are long-lived with an average life expectancy of 81.86 (Estes, 2002). However, behind the facade of economic prosperity and social stability, Hong Kong is indisputably a city of wealth disparity (Estes, 2005). In juxtaposition of economic growth, the Gini coefficient rose from 0.476 in 1991, to 0.518 in 1996, to 0.533 in 2006 (Pang & Lau, 2007). A recent UNDP report further reveals that while the richest 10 percent of the Hong Kong population takes 34.9 percent of all income, the poorest 10 percent take only 2.0 percent. Based on the latest figures, Hong Kong has 1.23 million people living on less than half of the median monthly income, indicating a poverty rate of 17.9 percent, or one in every six people in Hong Kong being poor (Einhorn, 2009).

The Hong Kong government has long adhered to the neo-liberal principles of maintaining a small government, underscoring a balanced budget and low taxation rate before and after the change of sovereignty in 1997. The Chief Executive, head of the government, gathers around a small number of Executive Council members who are mainly business magnates and pro-Beijing conservative politicians (Ho, Rochelle, Lee, Chan, & Wu, 2009). Having no (and no hope for) democratic electoral arrangements for the Chief Executive and the legislature (Sing, 2006), Hong Kong is managed according to neo-liberal, pro-capitalist and administrative- led ideologies without an effective countervailing force (Ho et al., 2009).

The government’s strategies to support mothers in poverty are increasingly salient and of concern as well. The latest anti-poverty initiative on “inter-generational poverty” simply ignores the here-and-now problems of poor mothers. As to the few job creation programmes launched in a handful of low-income communities, they are ad hoc measures that turn poor mothers into inexpensive laborers rather than long-term strategies to enhance the wellbeing of poor mothers and their families (“Job-creation Policy,” 2009).

Research in Hong Kong about women in general has shown that the married woman who has a higher education, higher childcare support, lower income, fewer children, and less traditional gender-role endorsement is more likely to work outside the home (Lau, Ma, & Chan, 2006). This pattern is somewhat similar to that found in Taiwan (Yi & Chien, 2002). The married woman also faces a negative sanction against divorce (Kung, Hung, & Chan, 2004). These findings suggest that married women with lower education in Hong Kong tend to be homemakers rather than working outside and leaving the marriage. Although older women in Hong Kong tend to be more satisfied with life and services (Lee & Kwok, 2005), mothers of low-income families and young children face difficulties in their childcare and family-work interplay and these deserve a thorough investigation in the present study.

Communities and Participants

It was within these social and policy contexts that we embarked on studying the decisions of mothers living in low-income communities in managing the dual-pressures from childcare and limited income. The mothers who participated in the study were selected through a multistage sampling procedure. The first stage was to identify collaborative primary/secondary schools located in the five communities: Tin Shui Wai (TSW), Sham Shui Po (SSP), Kwai Tsing (KT), Yau Mong (YM) and Tseung Kwan O (TKO). The next stage was to ask the schools to help identify potential mother respondents through students’ records. The mothers who took part in the study completed a self-administered survey. Targeting mainly mothers of children under age 13, the school classes chosen were from the higher grades for the primary schools, and lower grades for the secondary schools.

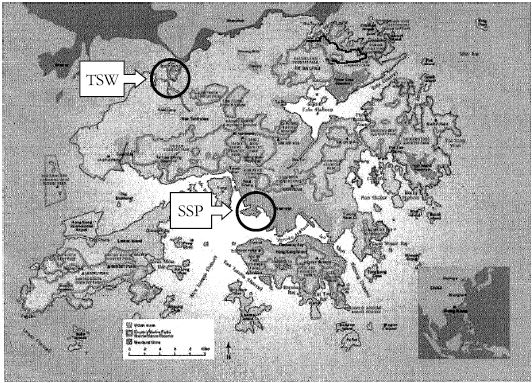

The survey collected data between October 2007 and April 2008, with an original sample group of 1,429 mothers. Among the five communities, TSW, SSP and KT were considered “low-income” with the median household income per member being less than half of the society median (i.e., less than HK$5,000); the other two (YM and TKO) were considered “non-low-income” communities. Due to limited resources, subsequent analyses will focus on respondents living in TSW and SSP (N = 889) of whom a proportion were in-depth interviewed either through household visits or telephone (N = 285). That said, the three communities other than TSW and SSP mainly acted as comparison groups in subsequent analyses. According to government statistics, TSW and SSP (Figure 1) had poorer populations and a higher proportion of new immigrants who had resided in Hong Kong for less than seven years (see Table 1).

In exploring the life-course decisions of these mothers, 285 (out of 889) respondents were purposefully selected for interviewing. Since we aim to understand more details about the life-course decisions of mothers who are poor and of immigrant backgrounds, respondents with both characteristics were preferred for interviews. After the number of respondents with these backgrounds had been exhausted, other inclusion criteria, including non-poor and local-born respondents, subsequently came into play (see Table 2). The interviews took place during May-September 2008. Before the deadline, 150 interviews were conducted with TSW respondents (51 household; 99 by telephone) and 135 with SSP respondents (46 household; 89 by telephone). The duration for in-depth interviews through household interviews ranged from 50 minutes to two hours while those through telephone interviews lasted from 20 minutes to 50 minutes. The response rate for completing the interview was 48.3 percent.

Key Variables in the Quantitative Analysis

Since the analysis of different age groups is essential to exploring life-course decisions, an age group variable must be constructed. The new variable “30s-40s” was then constructed to distinguish mothers aged 30-39 (“30s”) and aged 40-49 (“40s”). The variable was constructed according to several assumptions. It was estimated that many new immigrants came to Hong Kong around the age of 30, and that many women immigrants come to Hong Kong to join their husband and take care of children (Census and Statistics Department, 2006, p. 19). In fact, during our research, our contact with the migrant women suggested that most of their marriages were soon followed by childbirth. This pattern parallels the findings from extensive research on Southeast Asian “migrant wives” in Taiwan (Chou, Wang, Chiang, Lin, Kang, & Lee, 2006; Wang, Chung, Chou, & Chiang, 2006; Lin & Hung, 2007). The 30s and 40s are two categories approximate to the two life stages of launching and establishment often used in family studies (e.g., Amatea & Cross, 1983; Langan-Fox, 1991; Becker & Moen, 1999). “Launching” broadly refers to the life stage in which mothers are aged 27-39 years with children or expecting children; “establishment,” mothers aged 35-49 years who are married and have children (Becker & Moen, 1999, p. 997). In other words, this study focuses on how respondents adopt different life-course decisions during the transition from their 30s to 40s.

Consequently, the survey participants (N = 889) from TSW and SSP were aged 20 to 67 years (M = 41.2 years; SD = 5.9 years), and the participants interviewed (N = 285) were aged 29 to 60 years (M = 39.7 years; SD = 5.5 years).

In the analysis, this newly constructed age-group variable is to predict a number of outcome variables related to the work-family dilemma in the community. These variables included 1) the present employment status; 2) major factors considered when seeking jobs (childcare, location, time, salary, health, and job interest); 3) the perceived work-family tension; 4) number of children under the age of 13; and 5) perceived adequacy of family-friendly service in the community.

Procedures for In-depth Interviews

The individual in-depth interviews mainly tapped the respondents’ experiences in managing the dual demands of work and childcare. Before the respondents began to narrate their stories, the interviewees were sensitized with the answers that they gave earlier to the survey. In concrete terms, the answers given to three survey questions were reiterated. The three questions are: 1) “Generally speaking, when you need to work, who takes care of your kids?”; 2) “In general, what are the major factors you take into consideration when looking for jobs?”; and 3) “When you are to make a decision related to work, to what extent do you consider ‘childcare’ a determinant?” Such a method effectively helped respondents express their opinions on the matters in question. It also helped the interviewer to “break the ice” more efficiently with the interviewee, especially, during telephone interviews.

Results

Inter-community comparisons

In comparison with the two non-low-income communities (YM and TKO), mothers living in the three low-income communities had a significantly lower employment rate, worse relationship with their husbands, and lower chance of having relatives and domestic helpers to shoulder the burden of childcare (see Table 3). However, respondents from the two types of communities did not show a difference in the perceived adequacy of family-friendly services provided in the community.

These findings show that financial constraints notwithstanding, mothers living in low-income communities received significantly less family and social support than did those living in more well-off communities. That is, the mother in a better-off community was likely better off too, and this condition might contribute to her greater relief in childcare through the receipt of support. This picture dovetailed with a number of recent studies of low-income mothers (e.g., Judith, 2009; Joo, 2008; Usdansky & Wolf, 2008). In contrast, employment opportunity and services were equally available in low-income and better-off communities. This finding reasonably revealed that the financial conditions of the community or mothers did not determine employment and service conditions. The latter would be more a result of governmental and philanthropic arrangements than of residents’ wealth.

Differences between 30s and 40s Mothers

The analysis of the TSW and SSP data subset (N = 764) suggested that there were not significant differences in the divorce rate, educational level and poverty rate between the respondents from the two age groups (see Table 4). However, the 30s mother was more likely to have, at least, one child under 13, and have resided in Hong Kong for less than seven years. Furthermore, compared with the 40s mothers, the younger mothers were less likely to be employed at the time of the survey. Notably, more of the older mothers were in Shum Shui Po and conversely more of the younger mothers were in Tin Shui Wai. This finding also reflected that Sham Shui Po had a longer history of development than did Tin Shui Wai, which was a newly developed locale in the latest decade.

Regression analyses of life course on work-family conflict-related outcomes

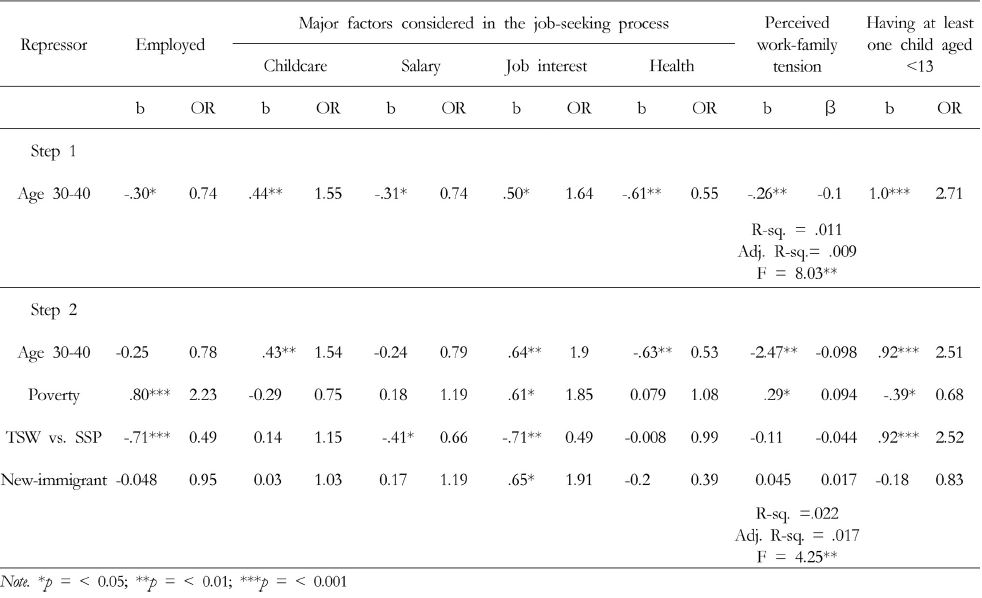

To assess the determinants of work-family tension and related conditions, linear and logistic regression analyses (depending on the data type of the outcome variable) showed differences due to age groups and other background characteristics. Results showed that the younger mother exhibited significantly higher concerns for childcare and job interest in job choice than did the older mother. The younger mother was also significantly more likely to have a child under 13 (see Table 5). However, the younger mother was significantly less likely to have employment, concerns with salary and health in job choice, and perceived work-family tension. These findings largely held both before and after controlling for other background characteristics. The exception was employment and concern for salary in job choice. In this connection, the community (SSP vs. TSW) displaced age group as a significant predictor of employment and salary concern. This reflected the case that the mother in Sham Shui Po was significantly older and less likely to have employment and a concern for salary than was the mother in Tin Shui Wai. Notably, the status of poverty tended to increase the chance of employment, concern for job interest in job choice, and perceived work-family tension. Besides, the new immigrant was significantly more concerned with job interest in job choice than was the other mother. Background characteristics would be basic antecedents to work-family tensions and related conditions.

The analyses so far have suggested that mothers in low-income communities faced serious constraints both in terms of family and social support networks than did those in the wealthier communities. In both TSW and SSP, the 30s mother suffered from significantly stronger feelings of conflicting work and family demands. Implicated in the analysis is that in the transition from one life stage (launching) to another (establishment), the mother adopted some life-course decisions to manage the work-care balance in the process. In contrast to the significance of the age or life course, migration was not decisive on the mother’s work and family conditions.

Although the statistical findings indicated some differences due to the migrant status, poverty status, and residential community, they might not be straightly generalizable because of the sample of mothers was not a random one, due to identification by the cooperating schools. Because of this caveat, the following qualitative data are necessary to illustrate details of the life-course decision.

Life-course decisions

Interviews largely reflected preceding statistical analysis that the 40s mothers expressed a higher degree of readiness to work than did the younger mothers and that the mothers living in SSP were more likely to be employed than were those in TSW. From the interview scripts, almost all respondents adopted what Becker and Moen (1999) called “scaling back” work arrangements, such as refusing to work overtime or conceiving work as a “job” rather than a “career.” These decisions were closely linked to the life-course perspective as the respondents, for most of the time, explained or justified their choosing of particular options in terms of life course-related events. This means that in their narratives, the respondents tended to lay emphasis on the change of their children’s ages as a determinant of particular decisions taken no matter whether the decisions concerned were used in the past or were to be adopted in the years to come.

In the interviews, these “scaling back” decisions emerged from mothers, as they were primarily responsible for childcare. Roughly speaking, less than six percent (17 out of 285) of respondents explicitly mentioned that their husbands were actively involved in childcare. The reason commonly used by most respondents to account for the limited spousal support was that their husbands were usually engaged in physically demanding jobs and worked long hours as truck drivers or construction workers.

Findings identified several scaling-back decisions adopted by respondents at various life stages and that the mothers from the two age groups did so differently.

“Placing limits on work”

The 40s mothers (identified by codes from A to Z in the quotes) showed higher readiness to take up fulltime jobs, though various limits on work were put in place such as cutting back on working hours, refusing to work overtime, choosing to work only the morning shift, and preferring jobs that allowed them to take leave in a timely and easy way. I’m afraid that no one will take care of the kids when I’m working. That’s why I asked to work the morning shift to make sure I can see them at night. I am afraid that they will hang around on the street at night (K, 40-cohort, SSP).

[The option of] [w]orking at night is not on. I need to take care of my kid, like preparing dinner. But, when my child was still small and in primary three [~=9 yr.], I didn’t even consider working (D, 40-s, SSP).

I had no option but to quit working once my boss wanted me to work at night. … To take care of my kid means that I cannot work (Jessica, 40s, TSW).

My job is a six-day job. However, I have the flexibility to plan my schedule. It offers me convenience to look after my kids (H, 40s, TSW).

Relatively fewer respondents in the 30s could express a feeling of “work-family-fit” as reflected in the narrative of Heidi (as quoted above). Only about five respondents (4.6%) from the young group could achieve such equilibrium in the work-care balance because of the help they obtained from relatives, or the delegation of care to formal careers, such as daycare or a home-help service. These cases were considered rare within the 30s mothers as the sample in general received a low level of social support for childcare and deemed their jobs as too low-earning to afford a professional care service; for example,

The salary earned from work might not be able to cover the cost of getting someone [professionally] to help [in childcare]. I will consider working when they [her kids] all, at least, are in primary school. Now, I prefer to take care of them fulltime (C, 30s, TSW).

One should note that even for a number of cases that the mothers could work part-time or freelance, it did not mean that a “work-family- fit” was really achieved.

I have a part-time job now as a cleaning lady. … I only work 4 to 5 hours every day. This schedule lets me take care of my kid. … But, I can’t spend much time with him during his summer vacation (S, 30-cohort, TSW).

My daughter is not old enough to look after her younger brother. So, I work [part-time] now. … Having worked for several months, I begin to find him [her son] no longer listening to me. … But, I have no choice. To work means that I can improve the living standard of the whole family (B, 40-cohort, SSP).

These narratives echo Wall and São José (2004, p. 592) who rightly remarked that it could be highly misleading to use the terms “reconciliation” and “balancing” to analyze family decisions to cope with the work-life conflict as if the equilibrium between the two spheres was always achieved at the end. In reality, the reconciliation of work and care may not always be possible from the subjective point of view of the mother as they might lead to negative feelings, or even guilt feelings on the part of the mother.

“Childcare is on top; a job is a job”

In general, the 30s mothers found the decision of “placing limits” unfeasible, or not desirable, as they tended to agree that their children were “still too young.” They emphasized repeatedly that caring for young children was their primary responsibility as mothers. Utterances like “childcare is the first priority,” “childcare is a mother’s responsibility,” “to look after children is of the most importance,” were often given. The majority expressed that they would consider working only when their children were old enough to attend primary school (≥ 6 yr.) or even secondary school (≥ 12). The worries expressed by mothers who chose to stay at home were mostly related to the possibility of domestic injury and poor neighborhood safety that would adversely affect their children.

I put childcare as my top priority. To bring a new life to this world means that I have the responsibility to take care of him. … Not until he grows up, say, reaching 15 years old, and is able to take care of himself that I will consider earning a living on my own (P, 30s, SSP).

I’m afraid that my kids will turn into bad kids [if I work]. They are still very young. I am afraid that they will hang around with bad people in the community. That’s why I insist that an adult must be there to look after them (H, 30s, TSW).

It is the mother’s responsibility to make sure that the children are safe. … It will be too dangerous to leave them alone at home. … I would feel guilty if my kids were injured while I am at work (A, 30s, TSW).

Such strong commitment to motherhood may be due to the substantial migrant background of the sample. Wall and São José (2004, p. 596) have astutely pointed out that the “mixed marriage migration pattern” where a foreign wife comes to live and build a family in her husband’s country of origin prompts the wife to give high priority to caring for young children and adopt a work-care decision which stresses the role of the mother as the main carer. The notion of “mixed marriage migration” can apply to our case in which the husbands were Hong Kong citizens at the time they married their China-born wives (Kung et al., 2004, p. 38).

In juxtaposition with the value of primacy given to childcare was the instrumentalization of the value of work. It means that even for the 40s mothers who felt less disturbed by the work-family tension, working means largely a short-term, money-earning activity rather than an essential self-satisfying process.

If not for the money, I would not choose to work. In the past, when he [her son] was young, I had to stay at home to take care of him. Now, he has just entered secondary school. I can work. … He complains that I do not spend much time with him. … His academic performance has been worsening. … I always tell him that I need to work to earn more money. … I wouldn’t work if I had enough money (M, 40s, TSW).

I am very worried about my kids. I make several telephone calls per night to make sure they are fine. … My job requires me to work at night. … To be frank, I would rather stay at home to take care of them if the [financial] situation of the family improves. … But, I do not have an option at the moment. Everything requires money (A, 40s, SSP).

This observation is in line with Becker and Moen’s study (1999) in which the authors identified the “job versus career” as the decision adopted mainly by women to strike a work-life balance. While jobs appeared in the previous study to be “ad hoc and flexible, more about making money than intrinsic satisfaction,” careers meant a work process progressing “in a straight line, and change less often, and are rewarding in themselves” (Becker & Moen, 1999, p. 1001). In our case, only eight respondents (three in the 40s; five in 30s) portrayed work as a means to self-actualization, and as a way to enhance their social integration. For the respondents who were working at the time of the interviews, most of them had a clear goal that a job was largely to help alleviate the financial hardship of the family.

Based on the narratives solicited from the sample, we would suggest that the conventional claim of “work-family conflict” does not apply to the mothers in question. It is because for the conflict to be real, it is assumed that employment brings about a sense of self-fulfillment and purpose in life (e.g., Smith, 2002, p. 54; Belenky, Bond, & Weinstock, 1997). However, in the interviews, work was seldom referred to as an identity-building process. Very often, working simply meant a means to remedy imminent financial difficulties that the family was facing.

“Public assistance is the last resort”

The extreme “scaling back” decision for at-home mothers under financial pressure was to receive public assistance (called Comprehensive Social Security Assistance or CSSA). The respondents, especially the 30s mothers, consider CSSA as the last resort when they had to take care of young children. Like the case of welfare mothers in the US, there has been a public stereotype among the Hong Kong populace that CSSA recipients are lazy and want easy handouts (Seccombe, 1999; Smith, 2002, p. 52). The majority of respondents expressed a negative view of CSSA when they spoke of the news report presented to them about a CSSA mother convicted of child neglect. Many considered the CSSA as a strong stigma that a mother must get rid of once her child reached a certain stage of self-care; otherwise the discrimination would be damaging and, in some cases, cross-generational.

In society, people taking CSSA are laughed at. People are scared of being identified as CSSA recipients. They will try not to be identified. … But, if there is a real need, one should take it. A mother has to wait for her children to grow a bit older, making sure that they do not turn into bad kids; then she can consider working and earning a living on her own (C, 40s, SSP).

If one has a strong need, such as when the kids are young, still in primary school, and can not act independently, or one has no one to turn to for childcare, it would be no problem to take CSSA. If all the kids are in secondary school, the mother should quit CSSA and consider doing part-time work. She should try to work and earn a living on her own. … Taking CSSA makes one become lazy. Many people deceive the authorities in order to get the money every month without doing anything (V, 30s, SSP).

Getting CSSA has a very negative influence on the children. They will be discriminated at school if their classmates know that their family receives CSSA. The mentality of the children will be adversely affected (P, 30s, TSW).

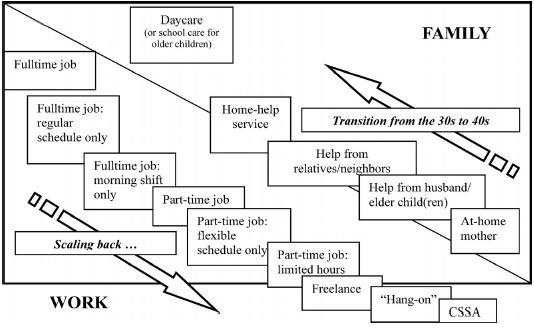

While the illustrations so far have schematically captured distinct life-course decisions that can be identified in the mothers’ narratives, the whole corpus of qualitative data reflected the spectrum of decisions that generally correspond to the respondents’ transition from the 30s to 40s (Figure 2). As the mothers become older, so do their children. With the children becoming less dependent, mothers are more willing to have them taken care of informally by elder siblings, relatives and neighbors and formally by home-help and daycare services. However, all these options are contingent upon the availability of these informal and formal means and the mothers’ capability to draw on the means. The respondents generally agreed that it was not until their children reached the age of 13 and were engaged in full-day secondary schooling that their perceived level of work-family conflict could effectively reduce and then they can be available for working fulltime. As we look into the nearly three hundred narratives one by one in order of descending age, a pattern of scaling-backing work decisions could be identified, which roughly ranges from choosing fulltime to part-time jobs, then to freelance; from regular shifts to flexible shifts, then to limited hours. Having insufficient social, family and professional resources in the community, poor mothers, especially those in the 30-cohort, generally said that their needs were not being met. The narratives suggested that they would be left “hanging” with the difficult situation on their own until their “children had grown up.” The very last resort would be to apply for the highly stigmatized CSSA. It was seen that the younger mothers of the 30s were more likely to position themselves in the lower right corner of the spectrum in Figure 3; and the older, 40s mothers could be more likely to progress toward the up left corner of the spectrum with a significantly lower level of perceived work-family conflict.

Discussion

Our analysis of the social and policy contexts indicate that the government has been inattentive to the dual-pressure of mothers living in low-income communities. The help provided to poor mothers has been remedial and limited, and mainly in terms of the highly stigmatized, cash-only CSSA scheme. Recent anti-poverty programming under the umbrellas of “tackling inter-generational poverty” and job creation either circumvents the everyday life problem faced by poor mothers or pushes them into the labor market without a genuine concern for the wellbeing of the mothers and their families.

Our survey findings reveal that mothers living in low-income communities generally lack substantial social and family support as well as the financial resources to hire domestic helpers to cope with the dual duties of childcare and work. The qualitative data further suggests that the mother is the one who shoulders most of the household duties and probably paid jobs as well, when the father works long hours in physically demanding jobs. The interview scripts point to the key argument of the present study that the degree of a mother’s perceived work-family conflict hinges on her life course. In particular, mothers in their 30s are more likely to experience strong work-family tension than those in their 40s. The main reason is that the 30s mothers are more likely to have children younger than 13 years of age, and when the support from the government is virtually non-existent, these mothers generally cannot be available for work even under difficult financial situations. This finding echoes that in Western research about young or new mothers’ concern with childcare (Goldberg & Perry-Jenkins, 2004). Importantly, these mothers are so committed to childcare that they are resentful about their reduced childcare role. Even in many cases when the young mothers with dependent children managed to balance the pressures of work and family care, they often regarded the arrangements as undesirable. Although not observable from the data, an explanation for the mothers’ preoccupation with the childcare role is that of evolutionary theory that regards the childcare or reproductive role as the woman’s prime criterion for deciding how to live her life (Taylor-Gooby, 2009). Accordingly, when the mother expects a low life chance, due to dire living, relocation, and marital conditions, she would turn to the reproductive role for fulfilling her life goal. Another reason is that the mother would like to depend on her children when she is old, and hence childcare would serve as an investment (Lee & Kwok, 2005). These explanations definitely require further investigations.

As shown in Figure 3 where the spectrum of decisions relevant to life courses were presented, mothers in their 30s are more likely to be positioned in the lower left-hand corner, being at-home mothers, and feeling helpless in face of the heavy home demands and financial pressure. Under this situation, public assistance (CSSA) would be their last resort. Only when the young mothers enter their 40s and their children become less dependent do they find the existing formal and informal support family-friendly in a way that enables them to take up paid work.

Apart from emphasizing age and childrearing, the life-course perspective maintains that life experience such as immigration and residency shape the mother’s employment and related interest (Clausen, 1986). In this connection, immigration and short residency tend to activate interest and engagement in employment. On the one hand, the contribution of immigration is consonant with existing theory and research that immigrants are more oriented to work because of their life experience of earning a living independently and adjustment generally (Tienda & Wilson, 1991; Wilson & Jaynes, 2000). On the other hand, the higher interest and engagement in employment of the mother dwelling in the earlier developed community in the inner city (i.e., Sham Shui Po), is consistent with existing theory and research about the higher work opportunity and the higher opportunity of non-work engagement there (Reingold, 1997; Hatch, 2007).

To conclude, capitalizing on mothers’ decisions pertinent to their life courses would be efficient to benefit the mothers as well as society. Accordingly, providing or mobilizing public support for 30s mothers’ childcare to upgrade its quality would fruitfully benefit from the mothers’ childcare commitment. Such support can include training and advice about childcare, including sustaining the health of both the mothers and children and aiding the mothers’ involvement in their children’s schooling. In contrast, public assistance in employment and facilitation of family-friendly employment environments would be valuable to 40s mothers. Essentially, some mothers with older children would like to enter employment and facilitation for their (re)entry is germane. A clue to the facilitation is the harnessing of the mother’s childcare experience and capability. Making such experience and talent gainful in employment and informing mothers about this is important to fulfill the mothers’ need for employment. Particularly facilitating the use of experience and talent is also a strategy to promote migrant mothers’ employment (Mays, Coleman, & Jackson, 1996; Wentling & Waight, 2001). A necessary antecedent to such facilitation is the identification of migrant mothers’ experience and talent that are different from those of locals and therefore lucrative for the mothers. For mothers living in communities far away from workplaces, provision of information and traveling assistance, or other subsidies for employment is appropriate, in view of these mothers’ higher interest in employment than those living in the inner city (Bartik, 2001; Millar, 2001).

Nevertheless, the implementation and success of differential public assistance strategies corresponding to mothers’ life course necessarily depend on further research. As the present study only launches an exploration into mothers’ life worlds, further research is indispensable to verify the findings in relation to systemic arrangements instituted by the government or public. Pertinent research on policy and practice is required to consolidate the base secured by the present study.

Notes

2 Second author

References

-

E. S. Amatea,, & E. G Cross,, (1983), Coupling and careers: A workshop for dual

career couples at the launching stage, Personnel & Guidance Journal, 62(1), p48-52.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2164-4918.1983.tb00119.x]

-

S. Asthana,, & J Halliday,, (2006), What works in tackling health inequalities? Pathways,

policies and practice through the lifecourse, Policy Press, Bristol, UK.

[https://doi.org/10.1332/policypress/9781861346742.001.0001]

- T. J Bartik,, (2001), Jobs for the poor: Can labor demand policies help?, Russell Sage, New York.

- P. Becker,, & P Moen,, (1999), Scaling back: Dual-career couples’ work-family strategies, Journal of Marriage & the Family, 61, p995-1007.

- M. F. Belenky,, L. A. Bond,, & J. S Weinstock, (1997), A tradition that has no name: Nurturing the development of people, families, and communities, Basic Books, New York.

- W. T. Bielby,, & D. D Bielby,, (1992), I will follow him: Family ties, gender-role beliefs, and reluctance to relocate for a better job, American Journal of Sociology, 97, p1241-1267.

-

K. L. Brewster,, & I Padavic,, (2002), No more kin care? Change in black mothers’

reliance on relatives for child care, 1977-94, Gender & Society, 16, p546-563.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243202016004008]

- J. E. Bruening,, & M. A Dixon,, (2008), Situating work–family negotiations within a life course perspective: Insights on the gendered experiences of NCAA Division I head coaching mothers, Sex Roles, 58, p10-23.

- L. Burton,, & A Snyder,, (1998), The invisible man revisited: Comments on the life course, history, and men’s roles in American families. In A. Booth (Ed.),, Men in families: When do they get involved? What difference does it make?, Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, p31-39.

- M. Cancian,, R. Haveman,, & D. R Meyer,, (2002), Before and After TANF: The Economic Well-being of Women Leaving Welfare, Social Service Review, 76, p603-641.

- Census and Statistics Department, Population By-census: Thematic Report: Persons from the Mainland Having Resided in Hong Kong for Less Than 7 Years, Census & Statistics Department, Hong Kong, China, (2006).

- P. H. Chou,, H, H. Wang,, Y. P. Chiang,, Y. R. Lin,, C. W. Kang,, & W.C Lee,, (2006), The pregnancy and labor experience of Southeast Asian women in transnational marriages, Journal of Evidence-Based Nursing, 2, p311-321.

- J. A Clausen,, (1986), The life course: A sociological perspective, Prentice-Hall, Englewood, NJ.

- P Collins,, (1994), Shifting the center: Race, class and feminist theorizing about motherhood. In D. Bassin & M. Honey (Eds.), Representations of motherhood, Routledge, New York, p56-74.

-

E Dahl,, (2003), Does workfare work? The Norwegian experience, International

Journal of Social Welfare, p274-288.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9671.00282]

- B Einhorn, (2009, October, 16), Countries with the biggest gaps between rich and poor, Business Week.

- G Elder,, (1999), Children of the great depression: Social change in life experience, Westview, Boulder, CO.

-

R. J Estes,, (2002), Toward a social development index of Hong Kong: The process

of community engagement, Social Indicators Research, 58, p313-341.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/0-306-47513-8_15]

-

R. J Estes,, (2005), Quality of life in Hong Kong: Past accomplishments and future

prospects, Social Indicators Research, 71, p183-229.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-004-8018-y]

- Foreign exchange reserves reach 258.3 billion, (2010, March, 8), Singtao Daily.

-

A. E. Goldberg,, & M Perry-Jenkins,, (2004), The division of labor and working

class women’s well-being across the transition to parenthood, Journal of Family

Psychology, 18, p225-236.

[https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.225]

-

P. Gyamfi,, J. Brooks-Gunn,, & A Jackson,, (2001), Associations between employment

and financial and parental stress in low-income single black mothers, Women & Health, 32, p119-135.

[https://doi.org/10.1300/J013v32n01_06]

-

S. L Hatch,, (2007), Economic stressors, social integration, and drug use among

women in an inner-city community, Journal of Drug Issues, 37, p257-280.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/002204260703700202]

- W. C. Ho, T. Rochelle,, W. L. Lee,, C. M. Chan,, & J Wu,, (2009), Controlling Hong Kong from far: The Chinese politics of elite absorption after the 2003 crisis, Issues & Studies, 45(3), p121-164.

- I. Hyman,, S. Guruge,, & R Mason,, (2008), The impact of migration on marital relationships: A study of Ethiopian immigrants in Toronto, Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 39(2), p149-163.

- A. P Jackson,, Black single working mothers in poverty: Preferences for employment, well-being, and perceptions of preschool-age children, Social Work, (1993), 38, p26-34.

- Job-creation policy is neglecting needs of women, says lawmaker, (2009, March, 8), South China Morning Post.

-

M. K Joo,, (2008), The impact of availability and generosity of subsidized child

care on low-income mothers’ hours of work, Journal of Policy Practice, 7(4), p298-313.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/15588740802261874]

- H Judith,, (2009), choosing work and family: poor and low-income mothers’ work-family commitments, Journal of Poverty, 13(2), p152-172.

-

I Julkunen,, (2002), Social and material deprivation among unemployed youth in

Northern Europe, Social Policy & Administration, 36, p235-253.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9515.00249]

-

A. l. Kalil,, & K. M Ziol-Guest,, (2005), Single mothers’ employment dynamics

and adolescent well-being, Child Development, 76, p196-211.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00839.x]

- R. F Kelly,, (1988), The urban underclass and the future of work-family research, Journal of Social Behavior & Personality, 3(4), p45-54.

-

R. Kjeldstad,, & M Ronsen,, (2004), Welfare rules, business cycles, and employment

dynamics among lone parents in Norway, Feminist Economics, 10(2), p61-89.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/1354570042000217720]

- W. Kung,, S. L Hung,, & C. L. W Chan,, (2004), How the socio-cultural context shapes women’s divorce experience in Hong Kong, Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 35, p33-50.

-

J Langan-Fox,, (1991), The stability of work, self and interpersonal goals in young

women and men, European Journal of Social Psychology, 21, p419-428.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420210505]

- Y. K. Lau,, J. L. C. Ma,, & Y. K Chan,, (2006), Labor force participation of married women in Hong Kong: A feminist perspective, Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 37(1), p93-112.

-

W. K. M. Lee,, & H. K Kwok,, (2005), Older women and family care in Hong

Kong: Differences in filial expectation and practices, Journal of Women & Aging, 17(½), p129-150.

[https://doi.org/10.1300/J074v17n01_10]

- L. H. Lin,, & C. H Hung,, (2007), Vietnamese women immigrants’ life adaptation, social support, and depression, Journal of Nursing Research, 15, p243-254.

-

A. S. London,, E. K. Scott,, & V Hunter,, (2004), Family reform, work-family

tradeoffs, and child well-being, Family Relations, 53, p148-158.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00005.x]

- R Mahon,, (2005), The OECD and the reconciliation agenda: Competing blueprints, (Occasional paper #20), Childcare Resource and Research Unit, Toronto, Canada.

-

M. J. Mattingly,, & S. M Bianchi,, (2003), Gender differences in the quantity and

quality of free time: The U.S. experience, Social Forces, 81, p999-1030.

[https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2003.0036]

-

V. Mays,, L. M. Coleman,, & J. S Jackson,, (1996), Perceived race-based discrimination,

employment status, and job stress in a national sample of black women:

Implications for health outcomes, Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 1(3), p319-329.

[https://doi.org/10.1037//1076-8998.1.3.319]

- J Millar,, (2001), Work-related activity requirements and labour market programmes for lone parents. In J. Millar (Ed.), Lone parents employment and social policy: Cross-national comparisons, Policy Press, Bristol, UK, p189-210.

- P. Moen,, & S Sweet,, (2003), Time clocks: couples’ work hour strategies. In P. Moen (Ed.), It’s about time: Career strains, strategies, and successes, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, p17-34.

-

P. Moen,, & S Sweet,, (2004), From ‘‘work-family” to “flexible careers”: A life

course reframing, Community, Work & Family, 7, p209-226.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/1366880042000245489]

- P. Moen,, & Y Yu,, (2000), Effective work/life strategies: Working couples, work conditions, gender, and life quality, Social Problems, 47, p291-326.

-

S. J Oliker,, (1995), Work commitment and constraint among mothers on

workfare, Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 24, p165-194.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/089124195024002002]

- D. Pang,, & M Lau,, (2007, June, 19), Gap wider between rich and poor, The Standard.

-

K Park,, (2008), ‘I can provide for my children’: Korean immigrant women’s

changing perspectives on work outside the home, Gender Issues, 25, p26-42.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s12147-008-9048-6]

- M. Pitt-Catsouphes, E. E. Kossek,, & S Sweet,, (2005), Charting new territory: Advancing multi-disciplinary perspectives, methods, and approaches in the study of work and family. In M. Pitt-Catsouphes, E. E. Kossek, & S. Sweet (Eds.), The work and family handbook: Multidisciplinary perspectives, methods, and approaches, Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah, N, p1-16.

-

D. A Reingold,, (1997), Does Inner city public housing exacerbate the employment

problems of its tenants?, Journal of Urban Affairs, 19(4), p469-486.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9906.1997.tb00507.x]

- A. Y. Rodgers,, & R. L Jones,, (1999), Grandmothers who are caregivers: An overlooked population, Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal, p455-466.

-

K Roy,, (2008), A life course perspective on fatherhood and family policies in the

United States and South Africa, Fathering: A Journal of Theory, Research, &

Practice about Men as Fathers, 6(2), p92-112.

[https://doi.org/10.3149/fth.0602.92]

- G. Russell,, & J Bourke,, (1999), Where does Australia fit in internationally with work and family issues?, Australian Bulletin of Labour, 25, p229-250.

- R. Sampson,, J. D. Morenoff,, & T Gannon-Rowley,, (2002), Assessing neighborhood effects: Social processes and new directions in research, Annual Review of Sociology, 51, p443-478.

-

I. Schoon,, & J Bynner,, (2003), Risk and resilience in the life course: Implications

for interventions and social policies, Journal of Youth Studies, 6, p21-31.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/1367626032000068145]

- K Seccombe,, (1999), So you think I drive a Cadillac? Welfare recipients’ perspectives on the system and its reform, Allyn and Bacon, Boston, MA.

-

M. J. Shanahan,, G. H. Elder,, & R. A Miech,, (1997), History and agency in

men’s lives: Pathways to achievement in cohort perspective, Sociology of

Education, 70, p54-67.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/2673192]

-

M Sing,, (2006), The legitimacy problem and democratic reform in Hong Kong, Journal of Contemporary China, 15, p517-532.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/10670560600736558]

-

J. R Smith,, (2002), Commitment to mothering and preference for employment:

The voices of women on public assistance with young children, Journal of

Children & Poverty, 8(1), p51-66.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/10796120220120386]

- H. Stier,, N. Lewin-Epstein,, & M Braun,, (2001), Welfare regimes, family- supportive policies, and women’s employment along the life-course, American Journal of Sociology, 106, p1731-1760.

-

S. Sweet,, R. Swisher,, & P Moen,, (2005), Selecting and assessing the family-

friendly community: Adaptive strategies of middle-class, dual-earner

couples, Family Relations, 54, p596-606.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2005.00344.x]

-

R. Swisher,, S. A. Sweet,, & P Moen,, (2004), The Family-Friendly Community

and its Life Course Fit for Dual-earner Couples, Journal of Marriage & Family, 66, p281-292.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2004.00020.x]

-

P Taylor-Gooby,, Reframing social citizenship, Oxford University

Press, Oxford, UK, (2009).

[https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199546701.001.0001]

- M. Tienda,, & F. D Wilson,, (1991), Migration, ethnicity, and labor force activity. In J. M. Abowd & R. B. Freeman (Eds.), Immigration, trade, and the labor market, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, p135-163.

-

M. L. Usdansky,, & Douglas A Wolf,, (2008), When child care breaks down:

Mothers’ experiences with child care problems and resulting missed work, Journal of Family Issues, 29, p1185-1210.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X08317045]

-

K. Wall,, & J São José, (2004), Managing work and care: A difficult challenge

for immigrant families, Social Policy & Administration, 39, p591-621.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9515.2004.00409.x]

- H. H. Wang,, U. L. Chung,, P. H. Chou,, & Y. P Chiang,, (2006), Physical and mental pressure: A survey on pregnant women in Taiwan who originally came from Southeast Asia, Journal of Health Management, 4(1), p89-101.

-

R. M. Wentling,, & C. L Waight,, (2001), Initiatives that Assist and Barriers that

Hinder the Successful Transition of Minority Youth into the Workplace in the

USA, Journal of Education & Work, p71-89.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080020028710]

-

M. Westman,, & C. S Piotrkowski, (1999), Work-family research in occupational

health psychology, Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 4, p301-306.

[https://doi.org/10.1037//1076-8998.4.4.301]

-

F. D. Wilson,, & G Jaynes, (2000), Migration and the employment and wages of

native and immigrant workers, Work & Occupations, 27, p135-167.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888400027002002]

- W. J Wilson,, (1997), When work disappears: The world of the new urban poor, Alfred A. Knopf, New York.

-

S Yeandle,, (1996), Work and care in the life course: Understanding the context for family arrangements, International Journal of Social Policy, 25, p507-527.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279400023928]

- C. C. Yi,, & W. Y Chien,, (2002), The linkage between work and family: Females’ employment patterns in three Chinese societies, Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 33, p451-74.