| >> Home | >> Journal Archive | >> For Contributors | >> Special Issue | >> About the Journal |

|

|

||

| Advanced Search >> |

|

The Effect of Household Modernization on Married Women’s Empowerment in Indonesia

| |

| Aurelija Rimkute |

:

Airlangga University, Indonesia |

| Lilik Sugiharti* |

:

Airlangga University, Indonesia |

| Correspondence: *Corresponding author | |

| Journal Information Journal ID (publisher-id): RIAW Journal : Asian Women ISSN: 1225-925X (Print) ISSN: 2586-5714 (Online) Publisher: Research Institute of Asian Women Sookmyung Women's University |

Article Information Received Day: 30 Month: 04 Year: 2024 Revised Day: 19 Month: 12 Year: 2024 Accepted Day: 23 Month: 12 Year: 2024 Print publication date: Day: 31 Month: 12 Year: 2024 Volume: 40 Issue: 4 First Page: 79 Last Page: 105 DOI: https://doi.org/10.14431/aw.2024.12.40.4.79 |

Abstract

This paper examines the effects of household modernization on married women’s empowerment in Indonesia, where the 1974 Marriage Law mandates women’s involvement in household affairs, amidst national efforts to achieve the fifth Sustainable Development Goal by 2030. Utilizing data from 28,453 married women aged 15–49 from the 2017 Indonesian Demographic and Health Survey, the study employs the Ordered Logit Model for estimation. The findings reveal that living in a decent, modern household (excluding motorcycle ownership) is associated with higher levels of empowerment among married women. Factors such as the number of children under five, higher levels of wives’ education, the age of both partners and their employment significantly enhance empowerment. Policy recommendations emphasize the need for subsidies for household appliances, gender equality initiatives that promote shared responsibilities, and programs encouraging personal achievements for young couples. The study also suggests that efforts to promote tertiary education for married women should focus on provinces with higher levels of empowerment.

Women’s empowerment, emphasized as the 5th goal of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs, 2021), is pivotal for achieving gender equality and unlocking the full potential of economies. In developing countries, women’s empowerment is largely contingent on their roles within households, particularly concerning the burdens of domestic labor (Gaffar, 2019; Standal & Winther, 2016; United Nations, 2021). Investigating the factors that influence household production is therefore crucial for understanding women’s empowerment.

Household modernization (HM) plays a crucial role in empowering married women by affecting their time allocation and opportunities for economic participation, as highlighted by the household production approach (Becker, 1965). Research shows that household appliances enhance women’s labor force participation and economic independence (Cardia, 2008; Dueso-Barroso, 2019; Greenwood et al., 2005; Tewari & Wang, 2021; Vidart, 2021), with these impacts being more pronounced among higher-skilled women, who can better utilize these resources and opportunities (Bose et al., 2020; Cardia, 2008; Chhay & Yamazaki, 2021; Dueso-Barroso, 2019; Rimkute & Sugiharti, 2023; Tewari & Wang, 2021; Vidart, 2021). Studies also suggest that empowered women tend to own more household goods, likely due to these goods providing greater autonomy and improving daily living (Voronca et al., 2017). However, few studies have specifically examined the empowerment benefits of electrification, which can enhance women’s access to information, increase productivity, and reduce time spent on domestic tasks (Bago et al., 2023; Sedai et al., 2020; Standal & Winther, 2016; Tenezakis & Tritah, 2019). Despite this, existing research does not sufficiently explore how HM adoption correlates with varying levels of women’s empowerment, highlighting a gap in understanding how different aspects of HM impact women’s empowerment across diverse contexts.

This study focuses on Indonesia, where raising awareness of women’s roles is crucial.

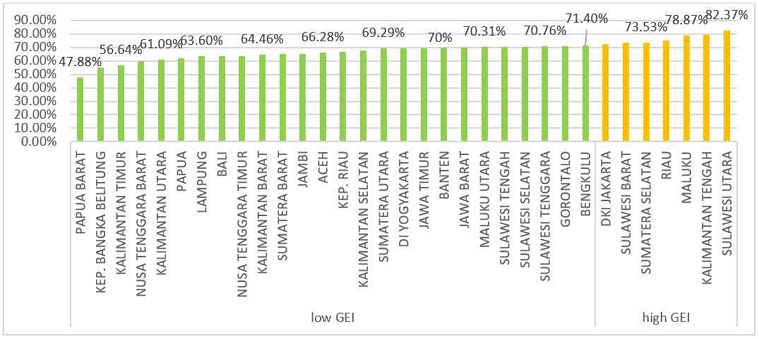

The 1974 Indonesian Marriage Law (Schaner & Das, 2016) assigns household chores to wives, emphasizing the importance of HM adoption in freeing time for women’s economic and social engagement. While some studies have explored the link between household appliances and women’s employment (Kusumawardhani et al., 2021; Rimkute & Sugiharti, 2023), they often overlook their broader impact on married women’s empowerment. There is also significant variation in the Gender Empowerment Index (GEI) across provinces, with Sulawesi Utara at 82.37% and Papua Barat at 47.88% in 2017, highlighting disparities in women’s progress toward equality (United Nations, 2021). Figure 1 divides the provinces into high GEI (above the national average of 71.75%) and low GEI (at or below the national average) (Badan Pusat Statistik (BPS) Indonesia Statistics, 2017), underscoring the need for a nuanced investigation into women’s empowerment from multiple perspectives in Indonesia.

Figure 1.

Gender Empowerment Index in Indonesian provinces in 2017.

Note. Badan Pusat Statistik (BPS) Indonesia Statistics, 2017

This paper aims to assess whether HM adoption influences the level of married women’s empowerment in Indonesia—categorizing it as lowest, medium, or highest. Additionally, it seeks to analyze the effects of HM across provinces, considering GEI. Utilizing data from the 2017 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), the term “modern households” encompasses adequate housing conditions (appropriate roofs, floors, walls, access to electricity, and modern toilets) alongside essential durables (washing machines, refrigerators, and motorcycles). The closest paper, Sedai et al. (2020), does not adequately capture the dynamics of change in married women’s empowerment related to access to electricity. Through the Ordered Logit Model (OLM), this research aims to fill the gap and advance our understanding of how HM diffusion relates to the varying degrees of married women’s empowerment in Indonesia.

The brief standpoint of empowerment is the “ability to make choices” (Kabeer, 1999; Annan et al., 2021). Empowerment indicators are reflected in various aspects of life, such as individual needs, household responsibilities, and behavior within the community (Samad & Zhang, 2019). Kabeer (1999) developed a framework for empowerment with three related domains: 1) access to resources, 2) agency in household decision-making, and 3) achievements. Other studies have expanded these domains by including factors such as a woman’s ability to travel alone outside her home, reproductive freedom, and social participation (Samad & Zhang, 2019). Additionally, the “resources” domain has been further divided into economic freedom (the decision to work) and economic decision-making regarding purchases (Sedai et., 2020). Therefore, it is important to recognize that empowerment can be understood from multiple perspectives.

The roots of married women’s empowerment lie within the household. Becker (1965) was a pioneer in discussing “the weight” of married women’s housework time on their time available for other activities. Theoretically, this decision involves trading leisure time and earnings to meet consumption needs (Borjas, 2016: 40). The perception of women’s roles within households and communities has evolved since the establishment of gender equality and rights in the early 20th century, including women’s rights to vote and participate in politics (Zhu & Chang, 2019). This struggle has continued into the 21st century, now focusing more on international agreements and policy formulation aimed at reducing gender-based discrimination and promoting equal opportunities (Dilli et al., 2019). Numerous studies (Bose et al., 2020; Cardia, 2008; Cavalcanti & Tavares, 2008; Chhay & Yamazaki, 2021; Dueso-Barroso, 2019; Greenwood et al., 2005; Tagliapietra et al., 2020; Tewari & Wang, 2021; Vidart, 2021) using datasets from different countries have provided positive evidence of women’s participation in the labor market.

Furthermore, some studies have shown significant effects of electrification on women’s empowerment within the National Program for Rural Electrification (PRONER) particularly through time-saving domestic work and the expansion of income-generating activities (Bago et al., 2023). The quality of electrification is positively significant for women's empowerment, but its effects vary depending on factors such as location, living standards, and education (Sedai et al., 2021). Many studies acknowledge that empowerment depends on household characteristics, such as household wealth (Voronca et al., 2017) or asset ownership (Annan et al., 2021). This assumption follows the idea that household members share the same vision of choices or presupposes that one member makes all the decisions while the other follows (Becker, 1981). Decreasing fertility rates will increase the labor force participation of married women (Borjas, 2016: 52). Women with children under five years old tend to be later to enter the labor market, and their labor supply is complementary to their spouse’s job.

Technological improvements affect female labor force participation (FLFP) rates in the process of household production because they improve efficiency, freeing up time for leisure activities and enabling women to enter the labor market (Borjas, 2016: 52). Technological advancements support living in more developed households, shape the time spent on housework, and influence the time available for other activities (such as combining careers and childbearing) for married women in America (Wellington, 2006). Electrification studies (Sedai et al., 2020; Standal & Winther, 2016; Tenezakis & Tritah, 2019) have attempted to investigate specific aspects of women’s empowerment. However, these studies do not consider other household management (HM) factors and do not examine how changes in living conditions in more modern households affect the empowerment levels of married women.

Some literature reveals that living in modern households does not empower women to have more time for housework (Bittman et al., 2004; Knapkova & Považanová, 2021; Vu, 2016. Household technological advancements benefit home-based working women in two ways: 1) flexibility to manage their time (Edwards & Field-Hendrey, 2002) and 2) the possibility of creating teleworking (home-based jobs) (Wynarcyk & Graham, 2013). The bargaining power model (Chiappori, 1988; Manser & Brown, 1980) shows that partners with greater access to resources, such as income and time, have more bargaining power and tend to achieve a more equal distribution of housework. The greater power of a partner depends on social norms and greater access to resources. In sum, social norms significantly impact married women’s empowerment by shaping gender roles, decision-making power, and access to resources, often limiting women’s opportunities and autonomy both within the household and in society.

Although existing literature provides valuable insights into women’s empowerment, there is limited research specifically focused on Indonesia. Some studies have explored the impact of information and communication technology (ICT) on women’s employment (Kusumawardhani et al., 2021; Sulistyaningrum et al., 2021). Using a multinomial logit model, one study highlights the varied effects of household technology (HM) adoption on married women’s occupations. While household technology strongly supports pink-collar jobs, white-collar jobs are more enhanced by ICT, and both factors show a negative relationship with blue-collar and agricultural work (Rimkute & Sugiharti, 2023). However, this research does not consider other dimensions of women’s empowerment, such as employment opportunities and decision-making roles within different job occupations.

This paper complements the limited studies on women’s empowerment in Indonesia, where traditional social norms predominantly position men as the primary breadwinners. While existing studies have explored various aspects of gender roles, few have examined how household modernization—particularly the reduction of housework—affects women’s empowerment. By focusing on household modernization as a key factor influencing women’s empowerment, as well, this research offers a novel perspective on how socio-economic variables intersect with gender dynamics. It provides a fresh analysis of how changes in household technology can empower women, offering new insights to the field.

In the unitary model (Ehrenberg & Smith, 2012: 214-215), couples share household responsibilities, while the bargaining model (Ehrenberg & Smith, 2012: 215; Manser & Brown, 1980) suggests that couples prioritize the partner with more resources. However, under the 1974 Indonesian Marriage Law (Schaner & Das, 2016), in both models, wives handle housework while husbands are the main breadwinners. This study argues that improved household conditions enhance wives’ empowerment (Sedai et al., 2020), as reduced housework burdens give women more time for other activities.

This study specifically investigates whether living in a modern household affects the empowerment levels of married women. An OLM is employed for estimation, as it effectively captures the ordinal nature of the dependent variable, i.e., empowerment levels in three categories: lowest, medium, and highest (Das, 2019:201). Each category reflects the varying degrees of empowerment experienced by married women. The OLM handles the level of women empowerment in the order from the lowest to the highest (Perez-Truglia, 2009:110): the lowest level of empowerment (j0) when Yi* ≤ α0; the medium level of empowerment (j1) when α0 ≤ Yi* ≤ α1; the highest level of empowerment (j2) when α1 ≤ Yi* ≤ α2, where α0 < α1 < α2; α0, α1, α2 – threshold parameters/cutoffs or intercepts. OLM method is more appropriate than the multinomial logit model since it sets categories of the dependent variable in order (Gujarati, 2012: 180; Perez-Truglia, 2009: 111-113). The Yi is an ordered response, and the values of married women’s empowerment levels are assigned to each outcome. In this model, Yi in trichotomous OLM determines two functions (Yi = 1 and Yi = 2) against the reference category (Yi = 0). The functions are estimated as follows:

(1) P(Yi=1)=g1(x)=lnP(Y=1|x)P(Y=0|x)=β10+β11HM1+β12SC1+ε1i

(2) P(Yi=2)=lnP(Y=2|x)P(Y=0|x)=β20+β21HM2+β22SC2+ε2i

Yi – is the level of empowerment for a married woman i. HMi – household modernization (a decent household index and modern household durables), SCi-socio-economic characteristics, ε1i, ε2i are error terms, and β10, β11, β12, β20, β21, β22 are parameters.

To interpret the results, the study calculates an odds ratio (OR) (Gujarati, 2012: 188-189), which indicates the relative contribution of household modernization and socio-economic characteristics to the empowerment levels of married women. An OR value greater than 1 suggests that the probability of achieving higher levels of empowerment increases with improvements in household modernization (HM) or socio-economic conditions (SC) compared to the reference group. Conversely, an OR value less than 1 implies that the likelihood of empowerment decreases as HM or SC diminishes.

When addressing issues of reverse causality, it is crucial to examine whether the increased adoption of household modernization is driven by factors associated with married women’s empowerment or by the innovations themselves. Studies such as Cavalcanti and Tavares (2008) argue that a strong correlation between the price of household devices and women’s participation in the labor market does not necessarily imply causation. Previous research, including work by Bose et al. (2020) and Sedai et al. (2020) using panel datasets, as well as Coen-Pirani et al. (2010) utilizing time-series data, has employed instrumental variable estimation to address endogeneity concerns. This method effectively isolates the causal effect of household modernization on women’s empowerment. Consistent with prior findings (Coen-Pirani et al., 2010), this study asserts that reverse causality does not significantly influence the primary conclusions regarding the impact of household modernization on married women’s empowerment.

The Indonesian IDHS provides microdata from 2017, the most recent dataset published by the U.S. Agency for International Development. The sample selection for the 2017 IDHS was based on two criteria: the 2010 population census and census blocks, each containing 25 randomly selected households. The sample includes 1,970 census blocks across 34 provinces in Indonesia (National Population and Family Board et al., 2018). IDHS Questionnaire was distributed to 50,730 women, yielding a 98% response rate. The observation unit consists of married women aged 15–49 (reproductive age), with a total sample size of 28,453 units. The IDHS data focuses on the reproductive age of married women and excludes older women, in line with the International Labor Organization’s definition of the working-age population.

Previous studies (Cardoso & Sorenson, 2017; Kirana & Indris, 2022; Kusumawardhani et al., 2021; O’Hara & Clement, 2018; Samad & Zhang, 2019; Sedai et al., 2020) identify fourteen primary variables associated with married women empowerment. Table 1 describes these variables. Using the Principal Component Analysis (PCA)1, the study estimated the index of married women’s empowerment. Five components of empowerment were selected based on eigenvalues greater than one2, which together explain 60.38% of the total variation. The PCA technique grouped the variables into five empowerment components: Economic Freedom, Household Decisions, Access to Resources, Agency, and Achievements. Based on the t-test, using LOS 5% there is a significant difference between the low and the high GEI provinces in terms of spending decisions, deciding to work, deciding on family visits, deciding on large purchases, having a bank account, having insurance, and decides on her healthcare. However, paid-for work, does not work for the family, deciding on a child’s medical treatment, using the internet and the existing name on the property’s rights are not significantly different.

Empowerment Variables

| Primary variables | Indonesia | Provinces with low GEI3 | Provinces with high GEI4 | t-test between low GEI and high GEI provinces | Compo-nent | Weight* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gets paid for work5 | 13,205 (46.41%) |

9,974 (46.51%) |

3,231 (46.10%) |

.6285 | Compo-nent 1 – Economic Freedom 25.24% |

0.53 |

| Does not work for family6 | 13,122 (46.12 %) |

9,951 (46.40%) |

3,171 (45.25%) |

.1223 | 0.51 | |

| Decision on spending her earnings7 | 12,781 (44.92%) |

7,244 (33,78%) |

2,258 (32.22%) |

.00133 | 0.52 | |

| Decides to work7 | 16,128 (56.61%) |

12,253 (57.14%) |

3,875 (55.29%) |

.0109 | 0.44 | |

| Decides for a child’s medical treatment5 | 24,921 (87.59%) |

18,658 (87%) |

6,263 (89.37%) |

.2819 | Compo-nent 2 – Household decisions 11.04% |

0.42 |

| Decides on family visits7 | 24,926 (87.60%) |

18,672 (87.07%) |

6,254 (89.24%) |

.0000 | 0.61 | |

| Decides for large purchases8 | 22,069 (77.56%) |

16,410 (76.52%) |

5,659 (80.75%) |

.0000 | 0.65 | |

| Has a bank account8 | 10,651 (37.43%) |

7,888 (36.78%) |

2,763 (39.43%) |

.0000 | Compo-nent 3 Access to resources 9.78% |

0.62 |

| Uses internet at least once a week9 | 8,838 (31.06%) |

6,564 (30.61%) |

2,274 (32.45%) |

.1528 | 0.67 | |

| Has an insurance10 | 17,788 (62.52%) |

13,277 (61.91%) |

4,511 (64.37%) |

.0001 | 0.34 | |

| Decides on her healthcare7 | 12,621 (44.36%) |

9,471 (44.16%) |

3,150 (44.95%) |

.0446 | Compo-nent 4 Agency 7.18% |

0.80 |

| Her name is on property’s papers5 | 4,759 (16.73%) |

3,587 (16.73%) |

1,172 (16.72%) |

.9801 | 0.47 | |

| Decides on using contraceptives5 | 17,648 (62.03%) |

13,312 (62.08%) |

4,336 (61.68%) |

.9438 | Compo-nent Achieve-ments 7.15% |

0.85 |

| Does not justify the wife-beating11 | 18,640 (65.51%) |

13,760 (64.16%) |

4,880 (69.63%) |

-0.36 | ||

| Number of married women (sample size N) | 28,453 (100%) |

21,445 (75.73%) |

7,008 (24.63%) |

Most women are empowered in Household Decisions, while just a few married women are involved in Access to the Resources and Agency. The majority of married women primarily focus on household decision-making, supporting the breadwinner theory (Gaffar, 2019; Zulkarnain et al., 2024), where women are socially prescribed to perform family tasks (Schaner & Das, 2016; Gaffar, 2019). However, the lowest number of married women have access to resources, suggesting that married women in Indonesia may not prioritize this access, as digital skills are perceived as non-feminine interests (Asriani & Ramdlaningrum, 2019). Additionally, Table 1 shows that few married women have bank accounts, a proxy for household bargaining power (Samad & Zhang, 2019), possibly due to preferences for cash transactions and high bank fees.

Regarding Agency, only 16.73% of married women have their names on property documents (house or land), and less than half make decisions about their healthcare. Studies indicate that agency is more difficult for married women to change, as it involves freedom of movement, which is often constrained by traditions (Abel et al., 2020; Chang et al., 2020). The persistent role of household duties for married women affects the dynamics of these components.

The essential component that reflects married women’s empowerment is Economic Freedom, while the least describing component is Achievements in Indonesia. For Economic Freedom, cash in hand for work activities has significantly the highest weight due to the benefits of more influence over the bargaining process in the household (Asriani & Ramdlaningrum, 2019). Working-paid women have more influence over bargaining than women with lower incomes (Barnett et al., 2021). However, half of married women do not decide on their earnings and are not engaged in work or work for the family. These numbers suggest that women’s work has some peculiarities in Indonesia: it is reproductive, cyclical, seasonal and unending (Gaffar, 2019), linked with responsibility for household chores.

The lowest weight in married women’s empowerment is attributed to the Achievements component (the fifth PCA component), which serves as a proxy for “well-being” (Kabeer, 2012), reflecting the capacity to make personal choices. Based on PCA estimation (Table 1), this component13 includes the use of contraceptives and women’s negative perceptions of wife-beating. In Indonesia, the patriarchal culture links wife-beating with the socio-cultural belief that men should dominate marital decisions and control their wives to maintain authority (Kirana & Idris, 2022; Saleh et al., 2022; Zulkarnain et al., 2024). Patriarchal norms suggest that wives should be restrained and forgiving. The low weight for contraceptive use reflects women’s limited capacity to manage their reproductive health (Efendi et al., 2023) and the desire for larger families (Kirana & Idris, 2022). The order of component weights reveals how patriarchal gender norms influence the acceptance of women’s repression in households, economic activities, and society.

Additionally, the descriptive results present the variables within two province groups based on GEI. The GEI measures gender gaps in political and economic representation (UNDP, 2009). In provinces with a higher GEI (above the national average14 of 71.75%), women experience greater empowerment across most factors, except for economic freedom. These outcomes are linked to the specific focus of the GEI, which emphasizes women’s opportunities to actively participate in economic and political life rather than their actual capabilities.

In this study, married women’s empowerment is measured using an index created through the PCA method. PCA is particularly useful for increasing the interpretability of large datasets by reducing their dimensionality while retaining key information (Jolliffe & Cadima, 2016). After applying PCA, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure (Reddy & Kulshrestha, 2019) was used to assess the sampling adequacy, resulting in a middling value of 77.79, which indicates that the data is suitable for this analysis. The PCA method produced five components, which together explain 60.38% of the total variation in married women’s empowerment. Specifically, the first component explains 25.24%, the second 11.04%, the third 9.78%, the fourth 7.18%, and the fifth 7.15%. These percentages reflect the varying importance of each factor in measuring overall empowerment, with the first component being the most influential and the fifth being the least. To construct the empowerment index (EImw), the study uses the proportion of these explained variations as weights for each component score, following the approach outlined in previous research (Krishnan, 2010). The weights are calculated based on the proportional differences in explained variance between consecutive components. For example, the first component explains 25.24% of the total variance, and it is weighted accordingly using the ratio of 0.2524/0.3627, reflecting its contribution relative to the total explained variance. The formula for the index is as follows:

EImw = (0.2524/0.3627)* (Component 1 score) + (0.3627-0.2524)/0.3627* (Component 2 score) + (0.4605-0.3627)/0.4606* (Component 3 score) + (0.5323-0.4605)/0.5323* (Component 4 score) + (0.6038-0.5232)/0.6038* (Component 5 score)

The index is constructed by applying these weights to the factor scores for each component, as estimated by PCA (see Table 1). The resulting dependent variable reflects the empowerment levels of married women, categorized into three levels: lowest (=1), medium (=2), and highest (=3). This index provides a comprehensive measure of married women’s empowerment, capturing the relative importance of different components in determining their overall empowerment status.

First, Table 2 displays the components of a decent residential index. The concept means that households have access to shelter, plumbing facilities, access to the drinking water, and durable housing with an eligible roof, eligible walls and eligible floors (BPS-Statistics Indonesia, 2023). More than 90% of married women live in households with access to electricity, finished walls, and finished roofs, yet just 71.37% of married women stay with modern toilets. In Indonesia, the modern toilet might not be the preferable primary attribute for households (Rimkute & Sugiharti, 2023). The Decent Residential Index is higher in provinces with a high GEI (4.44) compared to those with a low GEI (4.41), likely because sanitation and electricity depend on government policies, while other modernization factors are influenced by residents. There is a statistical difference in electricity access, modern toilet ownership, floors, roofs, refrigerators and washing machines, and motorcycles as well between the low GEI and the high GEI provinces.

Household modernization variables

| Name of variable | Description | Indonesia | Provinces with low GEI | Provinces with high GEI | t-test between low GEI provinces and high GEI provinces |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access to Electricity15 | The household has access to electricity (0- no, 1 – yes) | 27,523 (96.73%) |

20,705 (96.55%) |

6,818 (97.29%) |

.0056 |

| Modern toilet16 | The household has a private toilet with a septic tank) (0 – no, 1 – yes) | 20,217 (71.05%) |

15,038 (70.12%) |

5,179 (73.90%) |

.0000 |

| Floors17 | Floors are finished (0 – no, 1 – yes | 23,695 (83.28%) |

17,957 (83.74%) |

5,738 (81.88%) |

.0000 |

| Walls6 | Wall is finished (0 –no, 1 – yes) | 26,642 (93,64%) |

20,094 (93.70%) |

6,548 (93.44%) |

.3785 |

| Roof6 | Roof is finished (0 – no, 1 – yes) | 27,861 (97.92%) |

90,979 (97.83%) |

5,738 (81.88%) |

.0879 |

| Decent Residential Index | A continuous variable (the ownership of access to electricity, modern toilets, floors, walls, a roof) | 4,426177 (std. dev.-0.834842) |

4.419352 (std. dev. - .8443435) |

4.447061 (std. dev. - .8047915) |

.5689 |

| Refrigerator and Washing machine18 | The household has both durables (0 – no, 1 -yes) | 9,926 (34.89%) |

7,552 (35.22%) |

2,374 (33.88%) |

.0153 |

| Motorcycle19 | The household has a motorcycle (0 – no, 1 – yes) | 24,266 (85.28 %) |

18,385 (85.73%) |

5,881 (83.92%) |

.0012 |

In modern households in Indonesia, two key household items—refrigerators and washing machines—are essential, along with the motorcycle, the most common vehicle. Surprisingly, more married women live in households with motorcycles than with refrigerators or washing machines, with only 34.88% of married women residing in households that own both appliances. This suggests that while home appliances like refrigerators and washing machines are designed to reduce time spent on household chores such as cooking, grocery shopping, and laundry (Bose et al., 2020; Rimkute & Sugiharti, 2023), motorcycles fulfill a different need by reducing time spent on transportation tasks (Tewari & Wang, 2021; Rimkute & Sugiharti, 2023). Both appliances are similarly linked to reducing time spent on traditional housework, and their combined use reflects a shared function in easing domestic chores. By grouping these two appliances, the study accounts for their complementary roles in improving household efficiency, particularly in areas where socio-cultural factors like the high proportion of homemakers influence appliance ownership decisions. Additionally, in provinces with a higher GEI, ownership of washing machines and refrigerators is slightly lower than in provinces with a low GEI. Descriptive statistics show that in these higher GEI provinces, there is a reduced demand for appliances, due to the higher share of homemakers who often perform these tasks without relying on modern appliances (Bose et al., 2020) (Table 4).

Table 3 introduces the continuous socio-economic features that supplement the measurements of home production. The difference in women’s age, number of children under 5 years, and husband’s age are not significant in the low and high GEI provinces. Women’s empowerment is likely to depend on women’s life span as the duties of women change in different phases of age (Batool & Jadoon, 2018). The husband’s age might illustrate the perceptions of the wife’s role as the member in charge of household affairs (Duesso-Barosso, 2019). The number of children is a proxy of the care load (Duesso-Barroso, 2019; Sulistyaningrum et al., 2021), most married women have one child under five years old. The number of eligible women is a proxy of the support system for housework reduction or additional dependency (Rimkute & Sugiharti, 2023). In societies where women are primarily responsible for housework, the presence of other women who can assist reflects the broader support system in the household (Bittman et al., 2004; Kabeer, 1999; Rimkute & Sugiharti, 2023). Living with another woman can reduce the burden on one individual, but Table 3 reveals that the majority of married women live without such support. In Indonesia, cohabiting with female relatives like mothers, sisters, or mothers-in-law is common and beneficial, shaped by cultural values, economic factors, and gender roles(Setyonaluri et al., 2023). These living situations offer both practical and emotional support, helping share responsibilities and strengthen family unity.

Continuous Variables of Socio-economic Characteristics

| Characteristics | Description | Indonesia | Provinces with low GEI | Provinces with high GEI | t-test between low GEI provinces and high GEI provinces |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Woman’s age | Years | 35.652 (7.706) | 35.663 (7.669) | 35.618 (7.818) | .4502 |

| Children under 5 years old | People | .7373 (.745) | .736 (.736) | .742 (.772) | .9619 |

| Husbands’ age | Years | 40.119 (9.305) | 40.178 (9.273) | 39.940 (9.402) | .3075 |

| Eligible Women | People | 1.431 (.709) | 1.426 (.701) | 1.446 (.733) | .0183 |

Table 4 displays the categorical variables of socio-economic characteristics. The province is the proxy of the residence – the women in more developed areas enjoy greater infrastructure possibilities (Bose et al., 2020; Nazier & Ramadan, 2020). Just 13,48 % of married women have a higher education; this suggests that is not a priority for married women (Saleh et al., 2022). Married women belong either to occupations with skill levels or homemakers. Following the previous research findings (Rimkute & Sugiharti, 2023), the obligations of household duties affect the choice of occupations for married women. Yet, more married women are homemakers in the highly empowered provinces due to lower adoption of household appliances (Table 2). The husband’s characteristics (the level of education and occupation) might indicate his attitudes toward women’s empowerment (Rimkute & Sugiharti, 2023; Saleh et al., 2022; Thandar et al., 2019).

Categorical Variables of Socio-economic Characteristics

| Characteristics | Indonesia | Provinces with low GEI | Provinces with high GEI | t-test between low GEI and high GEI provinces |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Woman’s education level | ||||

| No education (=0) | 547 (1.92%) | 464 (2.16%) | 83 (1.83%) | .1351 |

| Primary education (=1) | 9,047 (31.80%) | 6,824 (31.82%) | 2,223 (31.72%) | |

| Secondary education (=2) | 15,024 (52.80%) | 11,264 (52.53%) | 3,760 (53.65%) | |

| Higher education (=3) | 3,835 (13.48%) | 2,893 (13.49%) | 942 (13.44%) | |

| Women’s Occupations20 | ||||

| Homemakers (= 0) | 10,819 (38.02%) | 7,993 (37.27%) | 2,826 (40.33%) | .0000 |

| Skills level 1 occupations (household, domestic) (= 1) | 4,507 (15.84%) | 3,577 (16.68%) | 930 (13.27%) | |

| Skills level 2 occupations (clerical, sales, agricultural, industrial, services) (= 2) | 11,231 (39.47%) | 8,426 (39.29%) | 2,805 (40.03%) | |

| Skills level 3 occupations (professional) (=3) | 1,896 (6.66%) | 1,449 (6.76%) | 447 (6.38%) | |

| Husband’s education level | ||||

| No education (=0) | 483 (1.70%) | 392 (1.83%) | 91 (1.30%) | .7839 |

| Primary education (=1) | 8,934 (31.40%) | 6,710 (31.29%) | 2,224 (31.74%) | |

| Secondary education (=2) | 15,368 (54.01%) | 11,519 (53.71%) | 3,849 (54.92%) | |

| Higher education (=3) | 3,668 (12.89%) | 2,824 (13.17%) | 844 (12.04 %) | |

| Husband’s Occupations | ||||

| Homemakers (=0) | 360 (1.27%) | 262 (1.22%) | 98 (1.40%) | .3959 |

| Skills level 1 occupations (household, domestic) (= 1) | 7,851 (27.59%) | 6,005 (28.00%) | 1,846 (26.34%) | |

| Skills level 2 occupations (clerical, sales, agricultural, industrial, services) (= 2) | 18,158 (63.82%) | 13,604 (63.44%) | 4,554 (64.98%) | |

| Skills level 3 occupations (professional) (=3) | 2,082 (7.32%) | 1,574 (7.34%) | 510 (7.28%) |

Focusing on the primary findings, Table 5 reveals that residing in modern and decent households significantly enhances women’s empowerment. As households become more developed, the odds of married women belonging to the high empowerment group, compared to those in the combined medium and low empowerment groups, increase by 1.08 times, with other variables held constant. Additionally, owning two key household devices increases women’s empowerment by 1.33 times compared to those in the combined medium and low empowerment groups. This suggests that these variables significantly reduce housework time for married women. This reduction is reflected in multiple dimensions, such as increased time for paid employment (Bose et al., 2020; Dueso-Barroso, 2019; Rimkute & Sugiharti, 2023; Vidart, 2021), greater bargaining power in household decisions (Sedai et al., 2020), improved well-being (Sedai et al., 2020), and enhanced access to resources, including skill development and healthcare (Voronca et al., 2017; Efendi et al., 2023).

Effects (OR) of HM and Socio-economic characteristics on Married Women Empowerment (the dependent variable = levels of married women empowerment)

| Variables | Indonesia | Provinces with low GEI | Provinces with high GEI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decent household index | 1.082282*** (.0201533) |

1.083807*** (.0234654) |

1.06797* (.0392024) |

| Adoption of a refrigerator and a washing machine (ref. – do not have both) | 1.329515*** (.0408108) |

1.348359*** (.0482446) |

1.290215*** (.0773769) |

| Motorcycle (ref. – do not have it) | 1.003371 (.041945) |

1.027157 (.0492928) |

.9065447 (.0777451) |

| Provinces with high GEI (ref. – provinces with low GEI) | 1.250804*** (.0367378) |

||

| Women’s age | 1.009259*** (.0029183) |

1.013912*** (.0034079) |

.995603 (.0056823) |

| Women’s education level No education |

Ref. |

Ref. |

Ref. |

| Primary education | 1.557862*** (.1667363) |

1.659706*** (.1929331) |

.9316768 (.2523159) |

| Secondary education | 2.031134*** (.2221576) |

2.150223*** (.2562571) |

1.224343 (.3359157) |

| Higher education | 4.66795*** (.5746975) |

5.105364*** (.692989) |

2.529706*** (.7527278) |

| Women’s occupation Not working |

Ref. |

Ref. |

Ref. |

| Skills level 1 occupations | 25.40206*** (1.225487) |

24.99403*** (1.380758) |

27.40108*** (2.744495) |

| Skills level 2 occupations | 96.29514*** (4.022331) |

95.84555*** (4.631416) |

100.6027*** (8.463082) |

| Skills level 3 occupations | 189.9588*** (16.90723) |

179.6484*** (18.0069) |

243.4707*** (48.02479) |

| Husband’s age | .9929034*** (.0023557) |

.9906639*** (.0027257) |

.9996079 (.0047044) |

| Husbands’ educational level No education |

Ref. |

Ref. |

Ref. |

| Primary education | .8831075 (.0974913) |

1.018532 (.1234002) |

.3986014*** (.110317) |

| Secondary education | .9799823 (.1097793) |

1.142819 (.1407774) |

.4264965*** (.1191703) |

| Higher education | 1.340745* (.1647073) |

1.523409*** (.2071812) |

.6455816 (.1929255) |

| Husbands’ occupations Not working |

Ref. |

Ref. |

Ref. |

| Skills level 1 occupations | .4634097*** (.057347) |

.5053958*** (.0722203) |

.3698426*** (.0929864) |

| Skills level 2 occupations | .6236418*** (.075588) |

.6699295*** (.0937342) |

.5241118*** (.1293556) |

| Skills level 3 occupations | .6491645*** (.0863878) |

.6726804** (.1033362) |

.6124387* (.1655218) |

| Children under 5 years old | .9355062*** (.0196021) |

.9301483*** (.0226844) |

.9507475 (.0391081) |

| Eligible Women | 1.021764 (.0201135) |

1.0084 (.0231867) |

1.062133 (.0406862) |

| Observations | 28,453 | 21,445 | 7,008 |

| LR chi2 (16) | 24325.52 | 18117.90 | 6219.49 |

| Prob > Chi2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Pseudo R2 Squared21 | 0.3734 | 0.3755 | 0.3719 |

Conversely, the ownership of motorcycles appears to have no impact on women’s empowerment in this study, which contrasts with findings from Tewari and Wang (2019). Given the high adoption rates of motorcycles in Indonesia (Table 2), this may suggest that motorcycles serve more as a necessity than a tool for empowerment, particularly in more empowered provinces where the significance of living in decent households diminishes.

Additionally, the number of children under five years old and the overall empowerment level of a province correlate positively with women’s empowerment. For women who have more children and live in provinces with higher GEI, the odds of married women in the high empowerment group, compared to those in the combined medium and low empowerment groups, are 1.25 and 0.94 times greater, respectively, with other variables held constant. This finding aligns with Siscawati et al. (2020), who argue that societal values surrounding women’s roles are reflected in provincial development programs. In line with previous studies (Annan et al., 2021; Nazier & Ramadan, 2020), the number of children in a household appears to empower women by enhancing their decision-making authority regarding family needs such as education, healthcare, and nutrition. However, the presence of additional women in the household does not yield similar empowerment benefits, contrary to the findings of Kandpal and Baylis (2019), indicating that the dynamics of empowerment are complex and context-dependent (cultural norms, economic conditions, policies, and interpersonal relationships). The gender equality programs in the provinces could focus on supporting the working women’s image, women’s life-work balance, paternity leave, and gaining new skills (for instance, digital skills, and entrepreneurship).

Regarding socio-economic characteristics of both wives and husbands, the analysis reveals that higher levels of education and employment for both partners positively influence married women’s empowerment, with particularly strong effects for individuals in skilled occupations. This supports Human Capital Theory (Ehrenberg & Smith, 2012; Johnson, 2023), which posits that skills and education enhance employment opportunities and, consequently, empowerment. Notably, this study echoes findings from Nazier and Ramadan (2019) and Thandar et al. (2019), which indicate that women benefit more from tertiary education in terms of labor market outcomes compared to men.

Moreover, the results suggest that husbands in higher-skilled occupations tend to exhibit more altruistic behavior (Chiappori et al., 1988), allowing for increased utility for their wives. This aligns with the labor-leisure model (Ehrenberg & Smith, 2012: 175-204), which posits that a husband's employment may constrain a wife’s decision-making power within the household. Additionally, the positive correlation between the ages of both partners and women’s empowerment further suggests that as couples age and achieve greater financial stability, gender equality in household dynamics improves (Batool & Jadoon, 2018; Nazier & Ramadan, 2020). Thus, the concepts of gender equality within households appear to strengthen with the age of both partners and their employment status.

This study highlights significant variations in GEI scores across provinces. Interestingly, while household appliances are positively associated with women’s empowerment, the broader impact of household modernization appears to be less significant in regions with high GEI. This suggests that, in these areas, factors beyond household technology may play a more significant role in influencing women’s empowerment. Consistent with earlier research (Rammon & Johar, 2014; Rimkute & Sugiharti, 2023), higher incomes and the educational levels of husbands have less impact on women’s empowerment in low GEI provinces, which aligns with Human Capital Theory (Borjas, 2016). Furthermore, in low GEI provinces, women with higher educational levels are more likely to experience empowerment compared to those without formal education. Tertiary education, in particular, significantly (5.11 times) boosts women’s empowerment, reflecting the more egalitarian environments that foster women’s education and development. Additionally, the estimation shows no significant correlation between women’s empowerment and the number of children under five in high GEM provinces. It suggests that women in high GEI provinces are less restricted by child-rearing duties due to better opportunities (Jager & Rohwer, 2009), challenging previous studies showing negative correlations in less empowered settings (Rimkute & Sugiharti, 2023).

In summary, this research underscores the multifaceted nature of women’s empowerment, illustrating that it is shaped by a combination of household conditions, individual socio-economic factors, and broader societal dynamics. Theoretical implications drawn from this study highlight the necessity of adopting a holistic approach to gender empowerment, one that recognizes the interconnectedness of various social factors and the need for targeted interventions that promote education, economic participation, and equitable household dynamics.

This study examines the impact of household modernization on married women’s empowerment in Indonesia, contributing to the fifth goal of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals. The findings reveal that decent and modern households significantly enhance women’s empowerment, except for motorcycle ownership. In response, the government should promote subsidies for household appliances and implement housing programs in less empowered provinces. Factors such as the presence of young children, higher levels of wives’ education, labor market participation, and the age of both partners also contribute positively to empowerment. Therefore, policies should focus on promoting shared household responsibilities and providing training programs for young couples. Additionally, in provinces with higher gender empowerment, initiatives should encourage tertiary education and professional development for married women to further enhance their empowerment. By implementing policies that enhance household conditions, promote education, and encourage equitable sharing of responsibilities, the government can significantly contribute to advancing women’s empowerment and achieving the broader objectives of sustainable development.

References

| 1. | Abel, M., Burger, R., & Piraino, P. (2020). The Value of Reference Letters: Experimental Evidence from South Africa. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 12(3), 40-71.

[https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20180666]

|

| 2. | Asriani, D. D., & Ramdlaningrum, H. (2019). Examining Women’s Roles in the Future of Work in Indonesia. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) foundation. Retrieved 30 January 2024 from https://asia.fes.de/news/examining-womens-roles-in-the-future-of-work-in-indonesia |

| 3. | Annan, J., Donald, A., Goldstein, M., Martinez, P. G., & Koolwal, G. (2021). Taking power: Women’s empowerment and household Well-being in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Development 140.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105292]

|

| 4. | Badan Pusat Statistik (BPS) Indonesia Statistics. (2017). Retrieved from https://www.bps.go.id/id |

| 5. | Bago, J. L, Djezou, W., Tiberti, L., Achy, L. (2023). Rural electrification and women's empowerment in Côte d’Ivoire. Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies, 14(1), 25-43.

[https://doi.org/10.1108/JADEE-11-2021-0295]

|

| 6. | Barnett, E. (2021). Towards an alternative approach to the implementation of education policy: A capabilities framework. Issues in Educational Research, 31(2), 387-403. |

| 7. | Batool, S.A., & Jadoon, A. K. (2018). Women’s Empowerment and Associated Age-Related Factors. Pakistan Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 16(2), 52-56. |

| 8. | Beavers, A. S., Lounsbury, J. W., Richards, J. K., Huck, S. W., Skolits, G. J., & Esquivel, S. L. (2013). Practical Considerations for Using Explanatory Factor Analysis in Educational Research. Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation, 18(6). |

| 9. | Becker, G. S. (1965). A Theory of the Allocation of Time. The Economic Journal, 75(299), 493-517.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/2228949]

|

| 10. | Becker, G. S. (1981). A Treatise on the Family. Enlarged Edition, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England. |

| 11. | Bittman, M., Rice, J. M., & Wajcman, J. (2004). Appliances and their impact: the ownership of domestic technology and time spent on household work. The British Journal of Sociology, 55(3), 401-423.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2004.00026.x]

|

| 12. | Bose, G., Jain, G., & Walker, S. (2020). Women’s Labour Force Participation and Technology Adoption (UNSW Economics Working Paper 2020-01). UNSW Business School. Retrieved 24 April 2024 from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3520613 |

| 13. | Borjas, G.J.. (2016). Labor economics. McGraw-Hill Education. |

| 14. | Cardia, E. (2008). Household Technology: Was it the Engine of Liberation? (Meeting Papers from Society for Economic Dynamics No. 826). Universite de Montreal. Retrieved 25 April 2024 from: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.192.7246&rep=rep1&type=pdf |

| 15. | Cardoso, L. F., & Sorenson, S. B. (2017). Violence Against Women and Household Ownership of Radios, Computers, and Phones in 20 Countries. Am J Public Health, 107(7), 1175-1181.

[https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.303808]

|

| 16. | Cavalcanti, T. V. de V., & Tavares, J. (2008). Assessing the engines of liberation: home appliances and female labour force participation. The review of Economics and Statistics, 90(1), 81-88.

[https://doi.org/10.1162/rest.90.1.81]

|

| 17. | Chiappori, P. A. (1988). Rational Household Labour Supply. Econometrica, 56(1), 63-89.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/1911842]

|

| 18. | Chang, W., Diaz-Martin, L., Gopalan, A., Guarnieri, E., Jayachandran, S., & Walsh, C. (2020). What works to enhance women’s agency: cross-cutting lessons from experimental and quasi-experimental studies (J-Pal Working Paper). Retrieved 26 April 2024 from: https://www.povertyactionlab.org/sites/default/files/research-paper/gender_womens-agency-review_2020-march-05.pdf |

| 19. | Chhay, P., & Yamazaki, K. (2021). Rural electrification and changes in employment structure in Cambodia. World Development, 137(C).

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105212]

|

| 20. | Coen-Pirani, D., Leon, A., & Lugauer, S. (2010). The effect of household appliances on female labour force participation: Evidence from microdata. Labour Economics, 17(3), 503-513.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2009.04.008]

|

| 21. | Das, P. (2019). Econometrics in Theory and Practices. Analysis of Cross Section, Time Series and Panel Data with Stata 15.1. Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-32-9019-8]

|

| 22. | Dilli et al., (2019). Introducing the Historical Gender Equality Index. Feminist Economics, 25(1), 31-57.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2018.1442582]

|

| 23. | Dueso-Barroso, J. (2019). Effects of home appliances on female labour participation in South Africa: Freeing women from housework (Magister Dissertation, Radboud University). Retrieved 24 April 2024 from: https://theses.ubn.ru.nl/handle/123456789/7827?locale-attribute=enMagister. |

| 24. | Edwards, L.N., & Field-Hendrey, E. (2002). Sci-Hubǀ Home-Based Work and Women’s Labor Force Decisions. Journal of Labor Economics, 20(1), 170-200.

[https://doi.org/10.1086/323936]

|

| 25. | Efendi, F., Sebayang, S. K., Astutik, E., Reisenhofer, S., & McKenna, L. (2023). Women’s empowerment and contraceptive use: Recent evidence from ASEAN countries. PLOS, 18(6).

[https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287442]

|

| 26. | Ehrenberg, R. G., & Smith, R. S. (2012). Modern Labor Economics: theory and public policy. (11th ed.). Boston: Pearson Education. |

| 27. | Zhu N, Chang L. (2019). Evolved but Not Fixed: A Life History Account of Gender Roles and Gender Inequality. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, Article 1709.

[https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01709]

|

| 28. | Gaffar, Z. H. (2019). Gender Roles, Work, and Women’s Mobility in Indonesia: Labor Migration Contexts. Journal Ilmu Sosial Humaniora, 24(1), 1-13.

[https://doi.org/10.26418/proyeksi.v24i1.2454]

|

| 29. | Greenwood, J., Seshadri, A., & Yorukoglu, M. (2005). Engines of Liberation. Review of Economic Studies, 72, 109-133.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/0034-6527.00326]

|

| 30. | Gujarati, D. N. (2012). Econometrics by Example. (5th ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. |

| 31. | International Labour Organization. (2024). International Classification of Occupations (ISCO). Retrieved 24 April 2024 from: https://ilostat.ilo.org/resources/concepts-and-definitions/classification-occupation/ |

| 32. | Jager, U., & Rohwer, A. (2009). Women’s Empowerment: Gender Related Indices as A Guide to Policy. Research Reports, IGI. |

| 33. | Johnson, N. N. (2023). Stabilizing and Empowering Women in Higher Education: Aligning, Centering, and Building. In H. Schnackenberg & D. Simard (Eds.), Stabilizing and Empowering Women in Higher Education: Realigning, Recentering, and Rebuilding (pp. 1-18). Retrieve from: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1057&context=cj_facpub.

[https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-6684-8597-2.ch001]

|

| 34. | Jolliffe, I.T., & Cadima, J. (2016). Principal Component Analysis: a review and recent developments. Philosophical Transaction. Series A Mathematical, physical, and Engineering Series, 13(374).

[https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2015.0202]

|

| 35. | Kabeer, N. (1999). Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women’s Empowerment. Development and Change, 30(3), 435-464.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7660.00125]

|

| 36. | Kabeer, N. (2012). Empowerment, Citizenship and Gender Justice: A Contribution to Locally Grounded Theories of Change in Women’s Lives. Ethics and Social Welfare, 6(3), 216-232.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/17496535.2012.704055]

|

| 37. | Kandpal, B. & Baylis, K. (2019). The social lives of married women: Peer effects in female autonomy and investments in children. Journal of Development Economics, 140C, 26-43.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2019.05.004]

|

| 38. | Kirana, K. & Idris, H. (2022). Determinants of Modern Contraceptives Use Among Married Women in Indonesia Urban. Jurnal Ilmu Kesehatan Masyarakat, 13(1), 85-96.

[https://doi.org/10.26553/jikm.2022.13.1.85-96]

|

| 39. | Knapkova, M., Považanová, M. (2021). (Un)Sustainability of the Time Devoted to Selected Housework – Evidence from Slovakia. Sustainability, 13(4), 2069.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042069]

|

| 40. | Krishnan, V. (2010). Constructing an Area-based Socioeconomic Index: A Principal Components Analysis Approach. Early Child Development Mapping Project Alberta. Retrieved 10 April 2024 from: https://www.ualberta.ca/community-university-partnership/media-library/community-university-partnership/research/ecmap-reports/seicupwebsite10april13-1.pdf |

| 41. | Kusumawardhani, N., Pramana, R., Saputri, N., & Suryadarma, D. (2021). Heterogeneous impact of internet availability on female labour market outcomes in an emerging economy: Evidence from Indonesia (WIDER Working Paper 2021/49). UNU-WIDER.

[https://doi.org/10.35188/UNUWIDER/2021/987-]

|

| 42. | Manser, M., & Brown, M. (1980). Marriage and Household Decision-Making: A Bargaining Analysis. International Economic Review, 21(1), 31-44.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/2526238]

|

| 43. | Nazier, H. & Ramadan, R. (2020). Is Women’s Empowerment A Community Affair? Community Level Application on Egyptian Women. International Journal of Euro-Mediterranean Studies, 13(1). |

| 44. | National Population and Family Planning Board, Statistics Indonesia, Ministry of Health & IFC (2018). Indonesian Demographic and Health Survey. BKKBN; BPS; Kemenkes; ICF. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR342/FR342.pdf |

| 45. | O’Hara, C. &, Clement, F. (2018). Power as agency: A critical reflection on the measurement of women’s empowerment in the development sector. World Development, 106(2018), 111-123.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.02.002]

|

| 46. | Perez-Truglia, R. (2009). Applied Econometrics using Stata. Cambridge: Harvard University. |

| 47. | Reddy, L. S., & Kulshrestha, P. (2019). Performing KMO and Bartlett’s Test for Factors Estimating the Warehouse Efficiency, Inventory and Customer Contentment for E-retail Supply Chain. International Journal for Research in Engineering Application & Management, 5(9). |

| 48. | Rimkute, A., & Sugiharti, L. (2023). The Link Between Occupations, Labor Force Participation of Married Women, and Household Technology in Indonesia. Journal of Population and Social Studies, 31(2023), 20-37.

[https://doi.org/10.25133/JPSSv312023.002]

|

| 49. | Saleh, A., Kuswanti, A., Amir, A. N., & Suhaeti, R. N. (2022). Determinants of Economic Empowerment and Women’s Roles Transfer. Jurnal Penyuluhan, 18(1), 118-133.

[https://doi.org/10.25015/18202238262]

|

| 50. | Samad, H., & Zhang, F. (2019). Electrification and Women’s Empowerment. Evidence from Rural India (Policy Research Working Paper 8796), World Bank. |

| 51. | Schaner, S., & Das, S. (2016). Female Labour Force Participation in Asia: Indonesia Country Study, (ADB Economics Working Paper Series No. 474), Asian Development Bank.

[https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2737842]

|

| 52. | Sedai, A. K., Nepal, R., & Jamasb, T. (2020). Electrification and Socio-Economic Empowerment of Women in India. The Energy Journal, 43(2)

[https://doi.org/10.5547/01956574.43.2.ased]

|

| 53. | Sedai, A. K., Vasudevan, R., Pena, A. A., Miller, R. (2021). Does reliable electrification reduce gender differences? Evidence from India. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 185 (2021), 580-601.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2021.03.015]

|

| 54. | Setyonaluri, D., Nasution, G., Ayunisa, F., Kharistiyanti, A., Sulistya, F. (2023). Social Norms and Women’s Economic Participation in Indonesia. Investing in Women. Smart Economies. Retrieved 16 Decemeber 2024 from https://investinginwomen.asia/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Lembaga-Demografi-Faculty-of-Economics-and-Business-Universitas-Indonesia-Social-Norms-and-Womens-Economic-Participation-1.pdf. |

| 55. | Siscawati, M., Adelina, S., Eveline, R., & Anggriani, S. (2020). Gender Equality and Women Empowerment in The National Development of Indonesia. Journal of Strategic and Global Studies, 2(2), Article 3. |

| 56. | Standal, K., & Winther, T. (2016). Empowerment Through Energy? Impact of Electricity on Care Work Practices and Gender Relations. Forum for Development Studies, 43(1), 27-45.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/08039410.2015.1134642]

|

| 57. | Sulistyaningrum, E., Resosudarmo, B. P., Falentina, A. T., & Darmawan, D. A. (2021). Can the internet buy working hours of married women in micro and small enterprises? Evidence from Yogyakarta, Indonesia, (ADBI Working Paper 1261). ADBI Institute. Retrieved 10 April 2024 from: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/700901/adbi-wp1261.pdf |

| 58. | Tagliapietra, G. Occhiali, E. Nano, & R. Kalcik (2020). The impact of electrification on labour market outcomes in Nigeria. Economia Politica, 37(3), 737-779.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-020-00189-2]

|

| 59. | Tenezakis, E., & Tritah A. (2019). Power for empowerment: impact of electricity on women and children in Sub-Sahara Africa. Paper presented at 2020 IZA Conference, 1-4 September. Available at: https://conference.iza.org/conference_files/worldbank_2020/tritah_a24922.pdf |

| 60. | Tewari, I., & Wang, Y. (2021). Durable ownership, time allocation, and female labor force participation: Evidence from China’s “Home Appliances to the Countryside” rebate. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 70(1), 87–127.

[https://doi.org/10.1086/706824]

|

| 61. | Thandar, M., Naing, W., & Moe, H. H. (2019). Women’s Empowerment in Myanmair: An Analysis of DHS Data for Married Women Age 15 – 49. DHS Working Paper, 143. Retrieved from https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/WP143/WP143.pdf |

| 62. | United Nations. (2021). The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2022. Retrieved 20 April 2024 from: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2021/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2021.pdf |

| 63. | United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2009). A User’s Guide to Measuring Gender-Sensitive Basic Service Delivery. Retrieved from: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/publications/users_guide_measuring_gender.pdf |

| 64. | Vidart, D. (2021). Human Capital, Female Employment, and Electricity: Evidence from the Early 20th Century United States (Working Paper 2021-08). University of Connecticut. Retrieved 10 April 2024 from: https://media.economics.uconn.edu/working/2021-08.pdf |

| 65. | Voronca, D., Walker, R. & Egede, L. E. (2017). Relationship between empowerment and wealth: trends and predictions in Kenya between 2003 and 2008-2009. Int J Public Health, 63(5), 641-649.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-017-1059-1]

|

| 66. | Vu, T. M. (2016). Home appliances and gender gap of time spent on unpaid housework: evidence using household data from Vietnam (AGI Working Paper 2016-18). Asian Growth Research Institute. Retrieved 14 April 2024 from: https://ideas.repec.org/p/agi/wpaper/00000115.html |

| 67. | Wellington, A.J. (2006). Self-employment: the new solution for balancing family and career? Labor Economics, 13(3), 357-386.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2004.10.005]

|

| 68. | Wynarcyk, P., & Graham. J. (2013). The impact of connectivity technology on home-based business venturing: The case of women in the North East of England. Local Economy, 28(5), 451-470.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0269094213491700]

|

| 69. | Zulkarnain, N., Rizki, D., Istiawati, S., & Saniah (2024). Wife beating in social and legal perspective In Indonesia. Pena: Justisia: Media Komunikasi dan Kajian Hukum, 22(3), 1-12.

[https://doi.org/10.31941/pj.v22i3.3954]

|

Biographical Note: Aurelija Rimkute is a postdoc fellow at Airlangga University. She is consistent in the realm of Gender Economics starting from her doctoral degree at Airlangga University. She is interested in issues of gender equality, women's participation in the labor market, and the burden of household production. E-mail: (arimkute@gmail.com)

Biographical Note: Lilik Sugiharti is a lecturer in Airlangga University-Indonesia since 1995. Her expertise is in Economic Development and Demography, but she is also interested in labor economics. Some research grants from Ministry Education Research and Technology of Indonesia have been achieved and Airlangga University as well. E-mail: (sugiharti.lilik@feb.unair.ac.id)

| Keywords: Women empowerment, married women, household modernization, Indonesia, Ordered Logit Model. |

|