Why Are Women Less Likely to Be Nationalistic in Taiwan?

Abstract

This article aims to resolve the paradox as to why, when the literature suggests that no fixed relationship exists between nationalism and gender, women in Taiwan are found in this study to be consistently less likely than men to support either Taiwanese or Chinese nationalism. To resolve this paradox, I first provide a detailed historical contextualization of the state-implemented nationalism to evince the contestation between feminism and nationalism under the authoritarian regime. Second, the long-term survey data available after democratization is employed to examine how men and women, who are asymmetrically affected by different concerns, will identify with the nationalistic projects differently in the current context. Combined with this empirical investigation conducted from a historical perspective, this study argues that women’s attitudes toward nationalism are shaped by the social constructs embedded within each nationalist discourse. Taiwanese experiences and nationalistic discourses have different impacts on women and men under different conditions, and the lesser nationalistic inclinations of women have been born out of this gendering process.

Keywords:

feminism, gender, Taiwanese/Chinese nationalism, pro-independence, pro-unification“Nationalism has typically sprung from masculinized memory, masculinized humiliation and masculinized hope” (Enloe, 1990, p. 44).

Introduction

As a post-colonial society, nationalism has long been the predominant political cleavage in Taiwan and has formed different constructs. This article concentrates on two nationalistic projects—pro-independence (from mainland China, Taiwanese nationalism) and pro-unification (with mainland China, Chinese nationalism)— which have been fervently debated and contested in Taiwan. Revolving around these two nationalistic poles, this study attempts to present a gendered and contextualized analysis of Taiwan’s nationalism issues, and to answer why women are less likely to support either of the nationalistic claims in Taiwan.

Many feminists have long been suspicious of male-centered national projects, questioning the lack of dialogue between nationalism and feminism, and have tried to re-imagine nationalism through gender lenses. Critics have argued that as an imaginative community, nationalism is often built upon masculinized bonds of comradeship and fraternity that exclude women’s experiences and accounts. Many feminists have recourse to Virginia Woolf’s famous words, “As a woman, I have no country. As a woman, I want no country. As a woman, my country is the whole world” (1938/1963, p. 108). These words have challenged the dominant national framework and have proposed that there be an alternative framework—a global sisterhood (Kaplan, Alarcon, & Moallem, 1999). Yet, Woolf’s claim was questioned by some third-world feminists who argued that only first-world privileged women are capable of taking such a high position (Blom, Hagemann, & Hall, 2000, p. 53). The struggle for women’s emancipation in many third-world countries cannot be separated from the fight against colonial powers and the democratic struggles for national independence (Jayawardena, 1986).

In different countries, we see different relationships, with no easy divide between first- and third-world feminism and nationalism (Ryan, 1997). Even within the same countries, there concurrently exist both contrasting and compatible relationships between nationalism and feminism (Vickers, 2006).1 This study starts with the premise that there is no essentialized relationship between feminism and nationalism. As Walby (2006) argued, the relationship between gender and nationalism is mostly affected by the associated values or projects raised within specific nationalistic contexts. Nationalism is a dynamic and fluid identity, and its relationship with gender, therefore, relies upon the contexts in which—and the ways in which—nationalism is constructed. This raises the following two highly pertinent questions: How is nationalism constructed in Taiwan? What are the gender implications of that construct?

To answer these questions, this article proceeds as follows. Following the Introduction, the second part reviews the evolution of state-implanted Chinese nationalism in Taiwan and how gender has embedded itself in the formation of that nationalism under the authoritarian regime. The third part proposes that, following democratization, Chinese nationalism and Taiwanese nationalism have constituted the main political cleavage in Taiwan, and that men and women who are asymmetrically affected by different concerns will identify with the nationalistic projects differently. To validate these propositions, the fourth part outlines the method used in this study, which is to describe the long-term survey data within its historical context. It then proceeds to present findings to explain why women are less likely to support Taiwanese nationalism and why more men than women tend to prefer Chinese nationalism, as the results of the long-term survey data indicate.

The contributions of this study are twofold. First, it describes in detail the historical context of state-implemented nationalism to evince the contestation between feminism and nationalism under the authoritarian regime. Second, it applies the long-term survey data available after democratization to examine how men and women who are asymmetrically affected by different concerns will identify with the nationalistic projects differently within the current context. With empirical substantiation, this study is able to demonstrate how the institutionalization of gendered norms within the nationalist discourse implies an uneven distribution of the costs and benefits of national identity between men and women (Thapar-Björkert, 2013). In short, the relationship between gender and nationalism is not fixed. Instead, it is determined by the way in which nationalism has taken shape in Taiwan.

The Gendered Features of State-implanted Chinese Nationalism under the Authoritarian Regime

Since the 1980s, many feminist scholars have challenged the gender-free assumption of nationalism studies inherent in the Gellner (1983) and Smith (1986) tradition, contending that nationalism is highly gendered and that gender has great significance for nationalism (Enloe, 1990; Jayawardena, 1986; Walby, 1992; Yuval-Davis, 1997; Yuval-Davis & Anthias, 1989). Gender-free nationalism is only made possible by regarding women as outsiders in various national projects. In history, women have long been excluded from, marginalized in, or subjectified by nationalist movements. Many feminists have raised a series of questions against nationalism: As the imagined communities, nationalism constitutes the cultural representation of sharing a set of identities and experiences among people. However, who has a full membership in these imagined communities? Have women participated or been represented within these imaginations? Whose memories or histories are they? How is gender embedded into a given imagination? In responding to these big questions, a gendered and critical review of Taiwan’s nationalistic projects from its inception may help reveal how multiple layers of the patriarchal order have been interwoven within a specific historical context.

In Taiwan, nationalism-related disputes stem from Taiwan’s complicated historical relationship with mainland China. Following Japanese colonial rule, which covered the period from 1895 to 1945, the Kuomintang (KMT) replaced imperial Japan as the ruling regime in Taiwan. Having retreated to Taiwan after losing the civil war in 1949 to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in mainland China, the KMT regime tried to re-build an orthodox Chinese nation-state in Taiwan, the Republic of China (ROC), which had been formally established on the mainland in 1912. This nation-state was to be a rival to the CCP’s newly established People’s Republic of China (PRC) in mainland China, as both the KMT and the CCP claimed to be the sole legitimate regime in China. The KMT regime that fled to Taiwan was composed of mainlander political elites that adopted the ideology of unification with mainland China (i.e., Chinese nationalism) as the official ideology and as the basis for the legitimacy of the KMT’s rule in Taiwan.

From 1949 to 1987, the nationalist projects (Chinese nationalism) under the KMT’s authoritarian regime perpetuated their related principle in the daily lives of Taiwan’s citizens and implanted a gender hierarchy as well. As Yuval-Davis (1997) argued, gender plays an important role in the biological, cultural, and political-citizenship reproduction of the nation-state. All three types of gendered regulations can be found in Taiwan’s national projects. In terms of biological reproduction, the KMT government regulated the role of women in reproduction to serve nationalistic needs. This ranged from requesting that women increase reproduction (thereby increasing the number of foot soldiers who would take back the mainland) to later regulating women’s birth rates (decreasing the birth rates in order to increase the quality of the citizen stock). The reproduction policy was prescribed under the Genetic Health Law enacted in 1984. The law itself is eugenics-oriented, as manifested in Article 1: “This law is duly enacted to enforce eugenics, upgrade population quality, protect the health of mothers and children, and bring added happiness to families.”2 In terms of nationality and citizenship, Chen’s (2006) study further showed that Taiwan’s regulation of nationality involved at least four types of gender biases: the subordinated status of women’s nationality, the prioritizing of fraternal nationality, the gender bias regarding the prerequisites and procedures of naturalization, and the gender bias in relation to the rights of citizens and unprotected immigrants. The newly re-established state not only relegated women to the status of biological reproducers of the nation but also designated a marginal status for women’s rights and citizenship.

In terms of the cultural and symbolic reproduction of nations, the gender regulations and norms embedded within the nationalist discourse are also evident in their dichotomous gender-role arrangement. From the outset, the Chinese-nationalism project under KMT rule assigned different roles to men and women along the lines of the Confucian tradition. Diamond (1975) compared Nazi Germany with the KMT’s authoritarian regime and found that the two regimes were strongly militaristic and strongly anti-communist, forcing allegiance to the state, to the leaders, and to nationalistic goals. In particular, the two regimes’ appropriation of gender exhibited many similarities. The ideal role for women in the Nazi and the KMT regimes was virtuous motherhood; child-rearing was held to be the most important role that a woman could play. To create a vigorous and consolidated national identity and to strengthen the nation, the nationalistic KMT regime educated women so that they would learn to become better wives and better mothers. In the private sphere, women were preoccupied with domesticity; however, the state would mobilize women for social service and auxiliary duties in the anti-communist struggle. In contrast to its treatment of women, the KMT regime tried to protect Taiwan from the PRC’s threats by assigning to men the mandatory role of being military recruits. The Taiwan government installed a compulsory military service system, in which men were compelled to enter the army as they reached a certain age.

The gender-role assignment in the nationalistic script was also built into Taiwan’s education system. To spread the nationalist orientation, the KMT instilled nationalism into the school curriculum along with the gendered divisions of war, with boys trained as soldiers and girls as nurses. All this state-sponsored nationalistic socialization sexualized the gender dichotomy in war and peace. Indeed, the naturalized gender roles, that is, women acting as mothers and reproducers versus men acting as soldiers and protectors of the nation (Kantola, 2016, p. 925), has been found to be central to the construction of state-promulgated nationalism in Taiwan.

Modernization uncovered another aspect of Taiwan’s gender relationships under the KMT nationalist regime. The traditional gender order embedded in the state-implemented nationalism plan changed with the state’s modernization. The best way for the KMT regime to defend its sovereignty in Taiwan against a possible invasion of the island by the Chinese Communist Party was to commit itself to building a wealthy and strong country. Modernization that would result in national material strength became the only choice. Consequently, during the 1960s and 1970s, as Taiwan experienced a dramatic economic expansion, the KMT government encouraged women to further their education and participate in the workforce to fuel economic expansion (Gallin, 1984). However, while modernization has given women more economic resources and autonomy, it would appear that the process of modernization has not substantially challenged their traditional roles in the patriarchal family system (Gallin, 1984; Greenhalgh, 1985, 1988; Xu & Lai, 2002). Some have referred to Taiwan as a modified patriarchal society that provides more job opportunities for highly educated women and has necessitated a new pattern in the gender power relationship (Farris, 1994; Xu & Lai, 2002). Despite still having its limitations, modernization has indeed benefited women substantially, both in their material conditions and in their individual autonomy.

In retrospect, in earlier times the authoritarian regime used to assign women very traditional roles and functions for nationalistic needs. Nevertheless, as the nationalist regime launched its modernization program in the late 1960s, traditional gender relations also gradually evolved into new forms and contents. The changing and contentious relationship between nationalism and gender illustrates that the gender implications of nationalism are in fact decided by the values and issues associated with specific nationalistic discourses. Perhaps Hall’s words best illustrate the paradoxical relationship between feminism and nationalism: “Nationalism has both made possible forms of activism for women which were previously impossible, and simultaneously limited their horizons” (Hall, 1993, p. 199). In fact, the KMT’s roots extend back to the formation of Asia’s first republic in 1912 and it has a long history of harnessing women for nationalistic causes in a somehow contradictory way in mainland China.3 In short, as to whether nationalist projects provide emancipation or enslavement for women is an ongoing debate (Vickers, 2006; Walby, 1992, 2006).

The Contestation between Nationalism and Gender after Democratization

Different national identities take shape, grow, and decline in different time periods. Yeh (2014) classified the official forms of nationalism constructed by state-led cultural and sociopolitical programs in post-war Taiwan into three waves: the Chinese nationalism from 1949 to 1987; the Taiwanese nationalism from 1988 to 2008; and practical-pro-Chinese nationalism after 2008. Each wave reflects the process and results of political transformation and competition for dominance of the national discourse. After the KMT lifted martial law and its ban on opposition parties in 1987, party competition intensified and became centered on the national-identity issue in almost every electoral competition (Wang, 2017).

From 1988 to 2008, after the 12-year term of the first native Taiwanese president, Lee Teng-hui, and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP)’s subsequent rule, the Taiwan-centered nativism that was built into the education and cultural policy resulted in a renaissance in the Taiwanese political identity (Chen, 2013). Taiwan was defined only as a part of China in the first wave of Chinese nation-building but was reinvented by Taiwanese nationalists as a valid nation in itself in the second wave (Yeh, 2014). However, Taiwan’s status quo as a de facto political entity has long been a matter of legal dispute. Taiwan’s further pursuit of de jure independence resisting China’s claim of sovereignty over Taiwan has invoked strong reactions from the Beijing government, including military threats. Several incidents since the 1990s reveal the connection between Taiwanese nationalism related to sovereignty claims and its consequences in the form of military threats from China (Chu, 2004; Hickey, 2013; Tung, 2002).4

In 2008, following the KMT’s victory in the presidential election, President Ma Ying-Jeou pursued a closer economic partnership with China by suspending political disputes. Taiwan and China had been separated for more than a century, having submitted to different political regimes while developing different socio-economic models. While Taiwan’s modern economic development began with the so-called Taiwan miracle during the 1960s and 1970s, at the same time China experienced the disastrous Cultural Revolution that hampered the country’s economic progress for more than a decade. However, as China launched its economic reforms starting in 1978, the Chinese economy gradually gained momentum and China emerged as a global economic power. In light of China’s rapid economic growth, and the relative economic slowdown in Taiwan, the cross-Strait relationship changed correspondingly. As China promoted a peaceful rise in economic terms, Beijing’s policy toward Taiwan gradually shifted from its reliance on military threats to pursuing unification through closer economic integration with Taiwan.

To explain the changing trend of national identity in Taiwan, Wu (1992, pp. 42–43) was the first to theorize that an individual’s national identity is shaped by two forces—affective attachments and rational considerations—and specifically by the interactions between these two forces. Affective attachments that are firmly rooted in a common language, culture, ethnic origins, or the sharing of a historical memory constitute an individual’s feelings of belonging, whereas rational concerns reflecting the costs and benefits involved in fulfilling the nationalistic goals are perceived as more changeable. People’s affective attachments to nationalism actually operate under the realistic conditions of Taiwan’s relationship with China. Nationalism in Taiwan has been associated with at least two predominant issues—the militaristic threat from mainland China and the materialistic gap across the Strait; yet each is weighted differently by men and women. When Taiwanese nationalism and Chinese nationalism are asymmetrically associated with militaristic attack and materialistic considerations, they will incur different gender dynamics. This study puts forward two propositions regarding the new gender dynamics revolving around the contestation over nationalism.

First, as Taiwanese nationalism (Taiwan’s independence) is associated with militaristic attack, it can be inferred that Taiwanese women who are marginal in this national discourse tend to be less enthusiastic about engagement with such national projects. Theoretically, the gender-dichotomized constructions of war and peace have several aspects. The stereotypically gendered division of soldiers/mothers rests on the socio-psychological assumption that women are less aggressive than men, are more likely than men to oppose war, and are more likely than men to find alternatives to violence in resolving conflicts (Elshtain, 1987; Goldstein, 2001; Peterson & Runyan, 1993). The gendered war–peace dichotomy might be socially constructed, but in practice women are frequently more pacifistic and less militaristic than men; women are more likely to oppose war and support the international peace movement than are men (Goldstein, 2001, pp. 322–331). Much of Taiwanese nationalism has revolved around militaristic attachment and defense, and consequently men have been elevated to the roles that are much more central than those undertaken by most women, who have in many ways remained marginal to the Taiwanese nationalist discourse.

Second, as Chinese nationalism (pro-unification) is connected with materialist considerations, most women whose interests have received weaker representation in national projects are less likely to support this nationalist project. Theoretically, despite the various national discourses on national unity, nations have long sanctioned the institutionalization of gender differences, and therefore nations as communities can be neither inclusive nor egalitarian. The nations’ cultures assign men and women distinct roles and benefits in accordance with gender norms (Mayer, 2000; McClintock, 1996). The Chinese nationalism involving cross-Strait economic integration often entails unequal access to rights and resources for men and women. Women and men occupy different social positions in Taiwan, and it is likely that Taiwanese women’s and men’s experiences and preferences regarding nationalism may diverge from each other. Women who find themselves excluded from the fruits of political and economic integration might disfavor this national project.

As nationalism develops into different forms that compete with each other, the gender dynamics also become more complex. The above two propositions are based on theoretical inferences. To substantiate these inferences, what follows will examine the empirical evidence.

Method and Data Analysis

This study addresses two main questions: Are Taiwanese women less likely to be nationalistic than men over time? Why are women less likely to be nationalistic than men? As discussed above, nationalism has long been a dynamic and constantly changing construct affected by related circumstances. Therefore, the answers to these two questions regarding the relationships between gender and national projects are most likely to be mediated by their association with other political projects or values.

First, to answer the question of whether women are less nationalistic than men in Taiwan, we can directly analyze men’s and women’s attitudes toward Chinese nationalism and Taiwanese nationalism. This study uses a long-term survey dataset, collected from 1992 to 2016 and administered by the National Chengchi University Election Study Center (ESC-NCCU). The beginning year of the dataset, 1992, is the year of Taiwan’s first congressional election after democratization. These national surveys, which are designed to examine the core political attitudes among Taiwanese, contain relevant questions on nationalism as it constitutes the main political cleavage in Taiwan. By analyzing people’s responses to the nationalistic questions based on their gender, we can get a general picture of how men’s and women’s reactions to these two nationalistic claims differ. The following standardized question that is directly related has been asked during each round of the survey between 1992 and 2016

- Q1: Concerning the relationship between Taiwan and mainland China, which of the following six positions do you agree with? 1. Immediate unification. 2. Immediate independence. 3. Maintain the status quo, move toward unification in the future. 4. Maintain the status quo, move toward independence in the future. 5. Maintain the status quo, decide either unification or independence in the future. 6. Maintain the status quo forever.

Second, to answer the question as to why women are less likely to be nationalistic than men, we have to pay attention to the issues and values associated with nationalism and their gender implications. As Wu (1992) argued, affective attachments and rational calculations have been the predominant factors in explaining the changing national identity in Taiwan. Individuals might either change their true identity (affective attachments) or hide their true preferences under the status quo option (Taiwan as a de facto state) as the realistic conditions change. The condition that constrains people’s affective attachments are Taiwan’s relations with China. On the one hand, Taiwan’s pursuit of independence would result in people resisting China’s claim of sovereignty over Taiwan, and the subsequent tensions across the Strait might provoke a major war between China and Taiwan. On the other hand, Taiwan’s pursuit of unification with China might provide Taiwan with some useful trade and market integration across the Strait; yet the political and economic developmental gaps across the Strait are significant barriers that the two sides would first have to overcome. Following Wu’s pioneering work, many studies on Taiwan’s national identity have come to agree that nationalism is constrained by these realistic issues involved with China (Chu, 2004; Hsieh & Niou, 2005; Keng, Chen, & Huang, 2006).

When nationalism is linked to these issues, men and women might have different attitudes toward nationalism owing to their different concerns and positions on the two issues of the military threat and socio-economic differences. Yang and Liu (2009) found that men and women were asymmetrically affected by the militaristic threats and realistic concerns associated with nationalist positions in Taiwan. Despite the shared theoretical concerns with this study, their study did not provide a historical contextualization of the nationalism issues in Taiwan and used a one-time survey (the 2005 Cross-Strait Relations and National Security Public Opinion Survey) to examine the possible associations between nationalism and gender. The survey they used did not directly address the question of people’s attitudes toward independence/unification under contrastive conditions, and the lack of long-term data did not enable them to perform a comparison over time. Because of the limitations of the existing research, this study extends the analysis to provide a historical perspective and an empirical analysis of the shifting pattern of both men and women in their national identity over time. This study also intends to address the limitations of a one-time survey by using a long-term dataset, the Taiwan Election and Democratization Studies (TEDS) survey, starting from 2004, when the contrastive nationalism questions were first asked, and ending in 2016, the year of the most recent presidential election. This dataset is based on the results of questionnaires administered by the ESC-NCCU after each of the respective presidential elections in order to investigate Taiwanese electoral attitudes and behaviors, including the most critical political cleavage, nationalism. Specifically, this study analyzes men’s and women’s responses to the following four questions regarding nationalism under contrastive conditions

- Q2-1: Do you agree or disagree that if Taiwan could still maintain peaceful relations with the PRC after declaring independence, then Taiwan should establish a new, independent country?

- Q2-2: Do you agree or disagree that even if the PRC decides to attack Taiwan after Taiwan declares independence, Taiwan should still become a new country?

- Q3-1: “If the economic, social, and political conditions are about the same in both mainland China and Taiwan, then the two sides should unify.” Do you agree or disagree with this statement?

- Q3-2: “Even if the gap between the economic, social, and political conditions in mainland China and Taiwan is quite large, the two sides should still unify.” Do you agree or disagree with this statement?

The next section will analyze the above five questions and illustrate how and why men and women might react to these two forms of nationalism differently because of different mediated issues associated with nationalism. I will first show that women are less likely to support either nationalistic claim in Taiwan. Next, I will examine whether the development of Taiwanese nationalism is linked to the peace–war opposition, in which case women who dislike war would be less supportive of Taiwan’s independence. Third, I will examine whether Chinese nationalism is linked to closer cross-Strait interactions, in which case women who gain relatively little from that interaction would be less likely than men to support unification. Relevant contextual explanations will be added to strengthen the robustness of the empirical evidence.

Finding 1: Whether Women Are Less Likely to Be Nationalistic

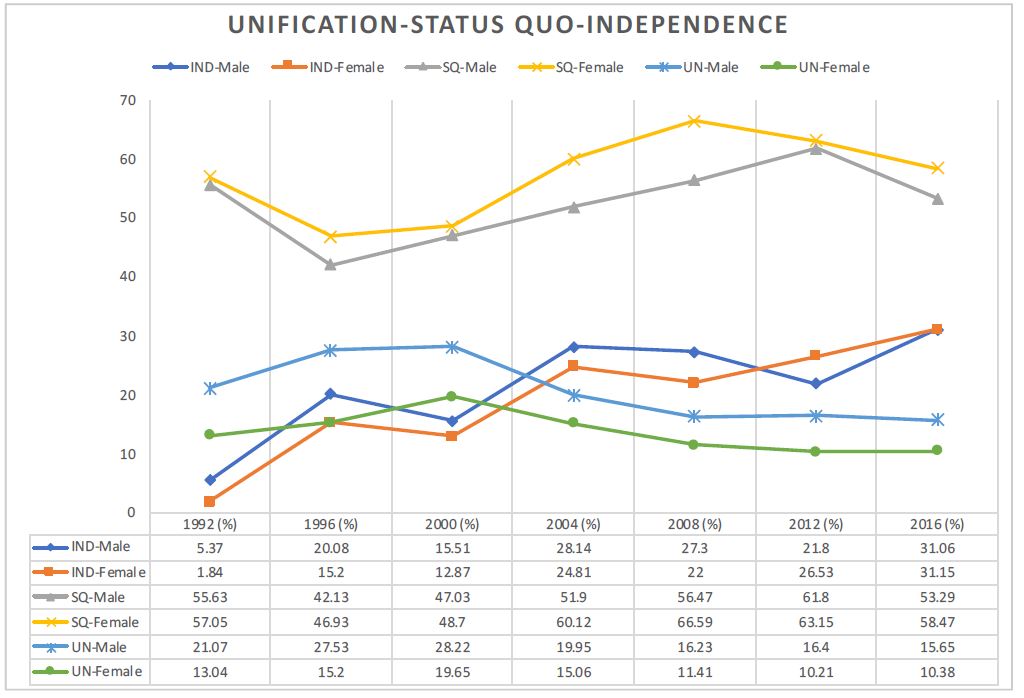

Most studies on Taiwan’s identity politics are concerned with the relations between national identity, ethnic identity, and party identity.5 Very few of the extant studies examine or explain gender patterns within the changing trends. To determine whether a gender pattern exists in nationalistic projects, this study analyzes people’s attitudes to the unification/independence question (Q1). Figure 1 shows the general trends and gender patterns regarding the different forms of Taiwan’s nationalism. As a whole, the general trend is indeed for different national identities to grow and decline in different time periods. In general, after 2000 the percentage of pro-unification supporters has declined and that of pro-independence supporters has been growing, with the percentage of pro-independence supporters surpassing that of pro-unification supporters by 2004. This trend is consistent with political changes. After the 12-year term of the first native Taiwanese president Lee Teng-hui (1988–2000), and in particular the DPP Chen Shui-bian presidency (2000–2008), the de-Sinicization movement has given rise to a growing Taiwanese consciousness. Still, maintaining the status quo in cross-Strait relations is the most popular option in Taiwan, a pattern consistent with existing findings (Wang, 2017).

The gender distribution of independence–status quo–unification in Taiwan (1992–2016). Adapted from “Core Political Attitudes among Taiwanese, National Chengchi University Election Study Center (ESC-NCCU).” IND-Male indicates the percentage of men supporting independence for Taiwan; IND-Female indicates the percentage of women supporting independence for Taiwan; SQ-Male indicates the percentage of men supporting the status quo; SQ-Female indicates the percentage of women supporting the status quo; UN-Male indicates the percentage of men supporting unification with China; UN-Female indicates the percentage of women supporting unification with China.

One trend has been almost constant across the time period observed, in that women have been less likely to support Taiwan independence than men, and men have been more likely to support unification with China than women. This gender pattern has remained relatively constant across the seven surveys included in this dataset, with the exception of women in 2012 having higher support than men for independence. In addition, women have been more likely than men to be supportive of the status quo. This might be attributed to the fact that women are more cautious about political change than men in that they do not want to change to either independence or unification. They like a status quo that appears to be working well. Overall, the gender pattern as it emerges in the context of nationalism is significant. Nevertheless, the pattern cannot be overstated because of the fact that Taiwan’s national identity is greatly affected by other cross-Strait issues, namely militaristic attacks and materialistic conditions. These factors themselves constitute explanations of the divergent pattern of nationalism found in women and men.

Finding 2-1: Why Pro-independence/Taiwanese Nationalism Is Less Favored by Women

Most people’s national identity undergoes constant change in response to constantly changing practical conditions. The primary and practical concern for Taiwanese nationalists is the military threat from China, which has never renounced the use of force to resolve the cross-Strait disputes. As Taiwanese nationalism seems likely to provoke an attack from China, a gendered war–peace dichotomy is implicated. In most male-dominated societies, men have gained exclusive control over the means of destruction, often in the name of protecting women and children (Peterson & Runyan, 1993, p. 81). In Taiwan, the government requires all men to take part in military training and encourages men to gain heroic honor by engaging—if necessary—in combat. However, it is in wartime that women are at risk of becoming victims of war-related rape or widowhood (Hynes, 2004). Historically, women have been victims of war in these and other unique ways.

Under Japanese colonial rule, the Japanese military forced some Taiwanese women to become comfort women, a type of sexual slave.6 The large-scale imprisonment and rape of thousands of women during this time demonstrates the fact that Taiwanese women were, in their own way, the victims of war crimes. Terms such as comfort women or voluntary corps were coined by the Japanese government and officials in an attempt to obscure the dreadful reality of drafting women for sexual service to Japanese troops. The practice of military comfort women demonstrates not only the institutionalized and collective rape of colonized women by Japanese soldiers, but also the trafficking of women (Watanabe, 1997). Likewise, in the civil war fought in mainland China, some women who did not participate in the civil war were forced to flee with their husbands to Taiwan, and later on, in the tragic 228 Incident that helped give rise to the Taiwanese native identity, many women who did not participate became widows. These historical facts help explain why some women in Taiwan have opposed militaristic or conflict-laden nationalism.

Furthermore, feminist groups have long been divided over issues related to nationalism. Many women’s organizations adopted a nonpartisan strategy for legislative lobbying. The political neutrality of feminist groups in national politics is by no means uncontested. In some elections, the debate over whether women’s solidarity should take precedence over women’s national identity has surfaced. However, most feminist groups agree that the national question should be resolved through peaceful means (Chang, 2009). The strategic disengagement of women from the war system and from militaristic nationalism is evident elsewhere in Taiwan. Yang and Liu’s study (2009) found that men and women were very different in their attitudes toward war, increasing weapons, a cross-Strait peace agreement, and security issues. On the one hand, women were more likely than men to adopt political and diplomatic approaches and sign a mutual peace agreement to solve the cross-Strait conflict. On the other hand, men were more likely than women to approve of arms purchasing and to take on active approaches involving war.

Whether women are more anti-war than men and how any such difference is related to women’s attitudes toward nationalism can be directly examined in our dataset from 2004 to 2016. The specific questions in the questionnaire related to the war–peace issue and Taiwan independence in this data set were Q2-1 and Q2-2, which asked if the respondents agreed or disagreed with the following statements: “If Taiwan could still maintain peaceful relations with the PRC after declaring independence, should Taiwan then establish a new, independent country?” and “Even if the PRC decides to attack Taiwan after Taiwan declares independence, should Taiwan still become a new country?”

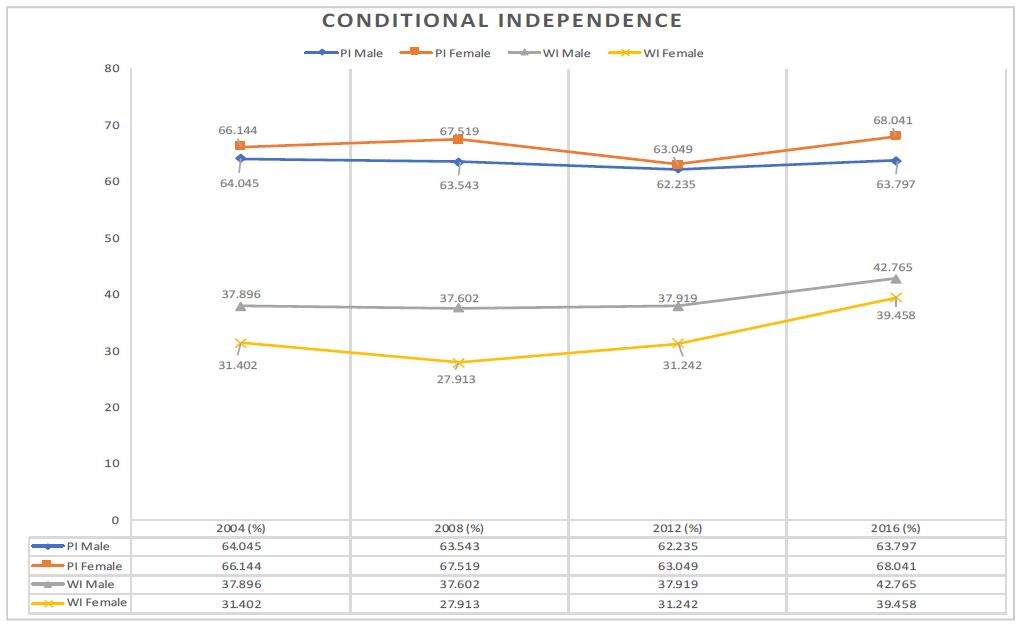

In Figure 2, those who agree with the first statement are labeled as Peaceful Independence (PI) supporters, whereas those who agree with the second statement are labeled as War Independence (WI) supporters. As a whole, respondents’ attitudes adjust with the conditions associated with unification, and the percentage of those supporting peaceful independence greatly exceeds that of those supporting militaristic independence by about 30 percent. Within the period observed from 2004 to 2016, the following gender pattern emerged: Women have been consistently more likely than men to support peaceful unification, and men have been consistently more likely than women to support unification even under the threat of the use of military force. War and peace have indeed had an important impact on women’s and men’s attitudes toward nationalism.

The gender distribution of conditional independence in Taiwan (2004–2016), Adapted from “National Chengchi University Election Study Center, TEDS2004P_ind, TEDS2008P_ind, TEDS2012, TEDS2016.” PI (Peaceful Independence) refers to those (%) who agree with the statement: “If Taiwan could still maintain peaceful relations with the PRC after declaring independence, then Taiwan should establish a new, independent country”; WI (War Independence) refers to those (%) who agree with the statement: “Even if the PRC decides to attack Taiwan after Taiwan declares independence, Taiwan should still become a new country.”

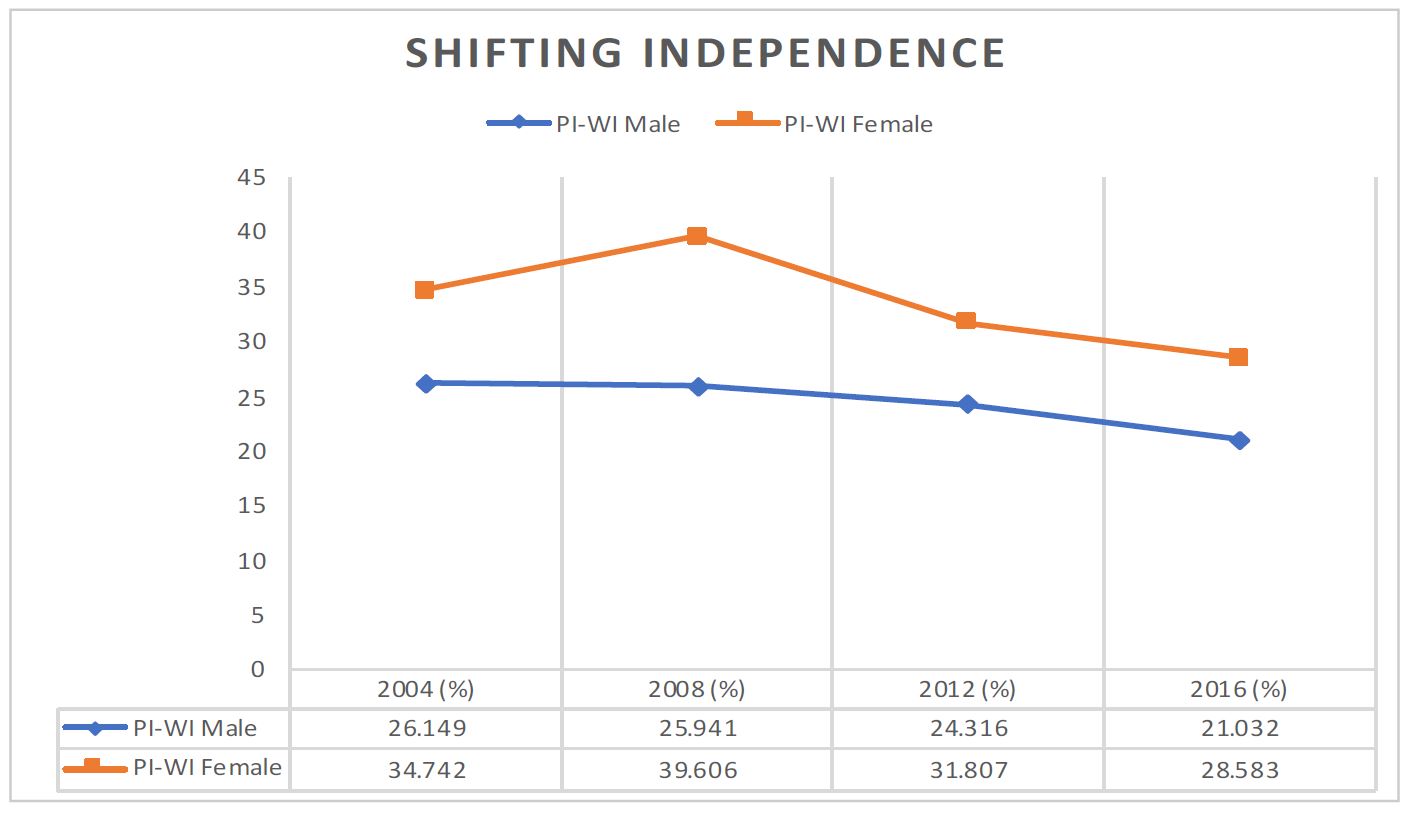

Women are more sensitive to the war–peace issues associated with independence, and Figure 3 further confirms this pattern. By deducting the percentage of those supporting militaristic independence from that of those supporting peaceful independence for both men and women separately, Figure 3 shows that the shifting gap on independence is bigger for women than for men. Women are more likely than men to change their position on Taiwanese independence according to the associated war–peace conditions. This suggests that women compared to men are not essentially averse to Taiwanese nationalism as long as it is achieved through peaceful means. Men and women think differently about war–peace issues related to cross-Strait relations and it is this difference that results in men’s attitudes toward Taiwan’s independence differing from those of women.

The gender distribution of shifting independence in Taiwan (2004–2016). Adapted from “National Chengchi University Election Study Center, TEDS2004P_ind, TEDS2008P_ind, TEDS2012, TEDS2016.” PI-WI male (Peaceful independence–War independence Male) is derived by deducting the percentage of men supporting militaristic independence from that of those supporting peaceful independence; PI-WI female (Peaceful independence–War independence female) is derived by deducting the percentage of women supporting militaristic independence from that of those supporting peaceful independence.

Finding 2-2: Why Pro-unification Chinese Nationalism Is Less Favored by Women

In pursuit of the unification of Taiwan with China, Chinese nationalists in Taiwan have had to deal with the differences between Taiwan’s and China’s development experiences across the Strait, ranging from the economic and the political to the social. Over the past decade, China has become Taiwan’s biggest trading partner (Tung, 2003). Economic cooperation across the Strait began to accelerate further when Ma Ying-Jeou of the KMT won the presidential election in 2008. However, the 2014 Sunflower movement exposed the fact that Taiwanese are both in need of and anxious about a closer relationship with China (Yang, 2016). The growing economic interdependence between the two sides further raises the question as to whether economic integration will eventually lead to some form of political unification. On March 18, 2014, the student movement, later known as the Sunflower Movement, occupied Taiwan’s Legislative Yuan, mobilized more than 500,000 people onto the streets, and awakened the public’s attention to the ongoing and speedy cross-Strait economic integration. The movement was triggered by the hasty passage of the Cross-Strait Services Trade Agreement (CSSTA) by a committee in the Legislative Yuan, bypassing the due legislative process. Many people, in particular the youth among Taiwanese nationalists, also expressed their concerns over how the growing economic interdependence might further jeopardize Taiwanese sovereignty, security, and autonomy, and facilitate China’s unification strategy.

Cross-Strait engagements have presented the Taiwanese people with both risks and opportunities. The impact of cross-Strait economic factors on nationalism are also weighted differently for both sexes. Men and women have gained different benefits and borne different costs in the integration process across the Strait. Interaction between the two sides remained almost non-existent until 1987 when the KMT government began to liberalize and, in particular, to lift the ban on Taiwanese people visiting their families in China. According to Keng’s observations (2002), from 1987 to 1999 most participants in the first wave of economic migration from Taiwan to China were businessmen and managers from small- and medium-sized enterprises in labor-intensive manufacturing industries. After 1998, in addition to the investors and managers, another wave of migrants to China emerged, mainly composed of highly educated and professional salaried men in the high technology, financial, and services sectors. The first wave was referred to as the “small businessmen” generation (Taishang), and the second wave was called the “informational people” generation. Regardless of whether these travelers were small business people or information people, they were almost always male. The vast majority of the earliest wave of business persons traveling from Taiwan to China were males who semi-permanently relocated to the mainland without any accompanying family. Only when living conditions improved in several cities in China did these traveling businessmen’s wives and children move to China to be alongside them (Wang, 2002).

Not only have Taiwanese men migrated more often than women to pursue economic interests, but it is also the case that women remaining in Taiwan have suffered more than men regarding the separation. Of the Taiwanese companies that set up factories in China, some closed their headquarters in Taiwan. These closures deprived many female Taiwanese workers of positive job opportunities because, in general, the companies relocated male but not female workers to China. Furthermore, married men who migrated to China by themselves left their wives behind in Taiwan to bear the entire responsibility of on-site child-care (if there were children) while the wives also feared that their husbands would take Chinese mistresses on the mainland (Shen, 2005). In response to this manifold problem, Taiwan’s legislature revised and enacted a new civil law whose clauses secure the property rights of wives in cases where husbands inappropriately transfer family property to China. The pattern whereby Taiwanese men migrate more often than Taiwanese women for economic reasons indicates that the gains from cross-Strait economic interaction constitute a highly gendered, male-favoring phenomenon.

Material conditions imply that there are different considerations for each of the sexes. In examining the different positions of women and men, we can identify women’s and men’s different experiences and expectations in the cross-Strait relationship. Compared to women, men have visited China more often and are more likely to work in professions that have benefited from the cross-Strait interactions (Yang & Liu, 2009). Generally speaking, individuals who visit the mainland relatively often are more likely than relatively infrequent visitors to support close ties between the two sides, and individuals who benefit from cross-Strait trade are more likely than individuals who do not benefit from it to prefer an open market linking Taiwan with China.

People’s attitudes toward unification with mainland China are thus shaped by material and political conditions. These materialistic conditions have different gender implications. The specific questions in the questionnaire related to the materialistic conditions and unification in this data set are Q3-1 and Q3-2, asking if the respondents agreed or disagreed with the statements: “If the economic, social, and political conditions were about the same in both mainland China and Taiwan, then the two sides should unify” and “Even if the gap between the economic, social, and political conditions in mainland China and Taiwan is quite large, the two sides should still unify.”

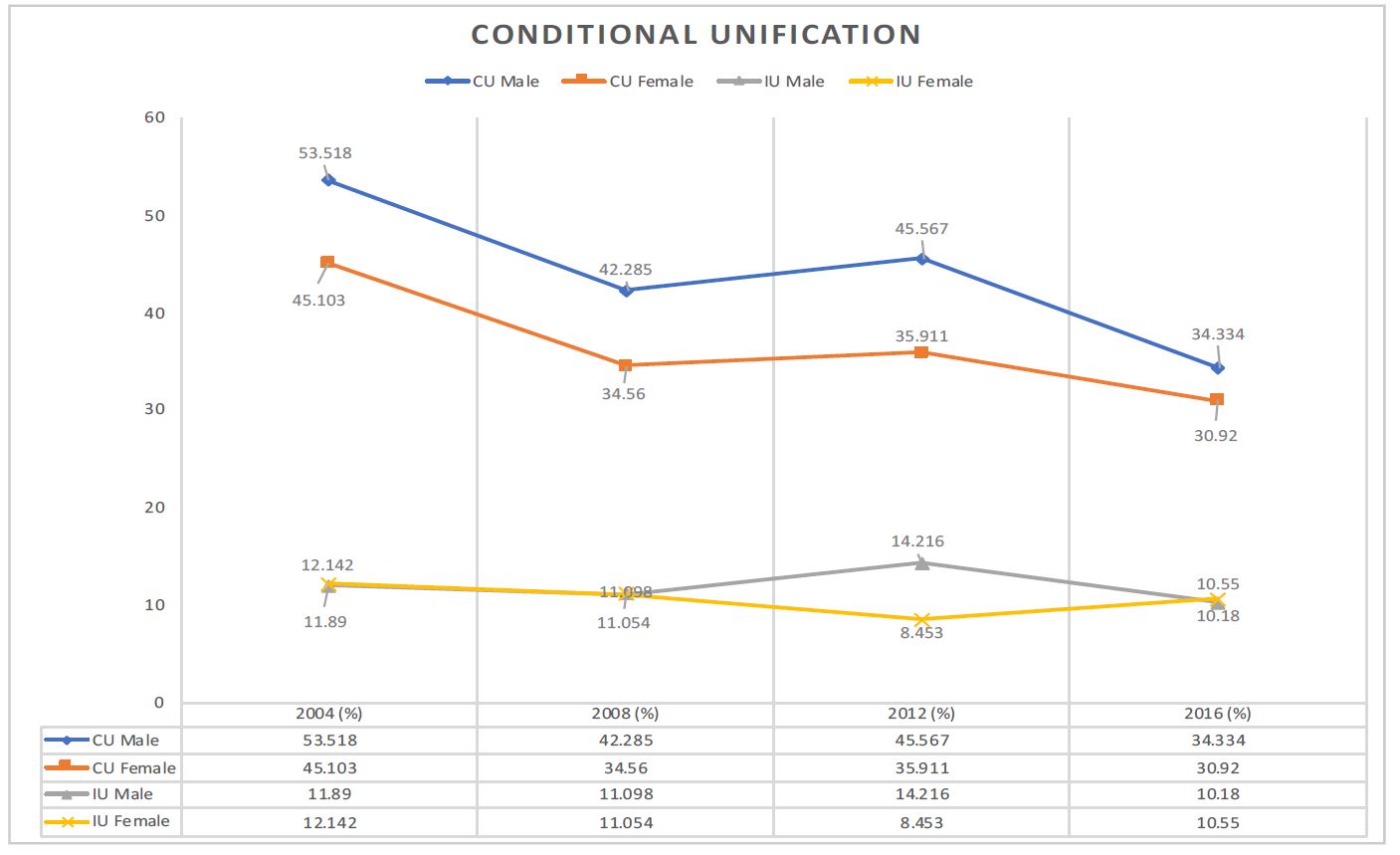

In Figure 4, those who agree with the first statement are labeled as Compatible unification (CU) supporters, whereas those who agree with the second statement are referred to as Incompatible unification (DU) supporters. Figure 4 shows that, in general, the percentage of those supporting compatible unification is higher than that of those supporting incompatible unification. The results further show that male respondents have consistently been more likely than female respondents to support unification when the mainland and Taiwan become more compatible over time. Men who benefit more from the cross-Strait interactions are more likely to be tempted and moved by the economic-cum-political integration. The gender gap narrows when the two sides are not compatible, with smaller percentages for both men and women (about 10%) approving of incompatible unification.

The gender distribution of conditional unification in Taiwan (2004–2016). Adapted from “National Chengchi University Election Study Center, TEDS2004P_ind, TEDS2008P_ind, TEDS2012, TEDS2016.” CU (Compatible Unification) refers to those (%) who agree with the statement: “If the economic, social, and political conditions were about the same in both mainland China and Taiwan, then the two sides should unify”; DU (Incompatible Unification) refers to those (%) who agree with the statement: “Even if the gap between the economic, social, and political conditions in mainland China and Taiwan is quite large, the two sides should still unify.”

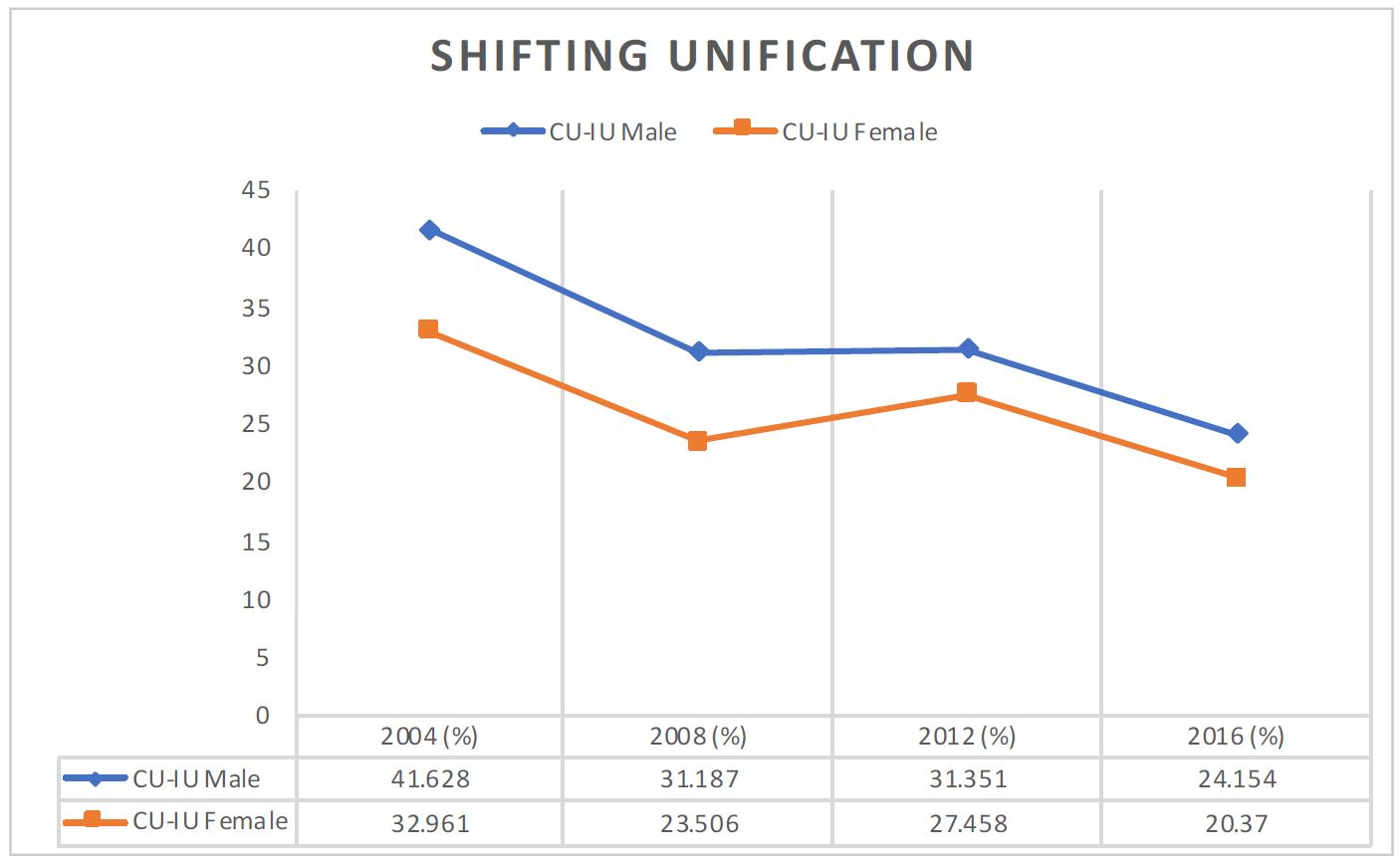

Figure 5 further deducts the percentage of those supporting incompatible unification from those supporting compatible unification for men and women separately. Men are more likely to alter their attitudes toward unification when the political and socioeconomic gaps change. These results suggest that women and men occupy different positions on cross-Strait interactions and own different interests, and these differences might lead men and women to differ from each other regarding their concerns over cross-Strait political unification.

The gender distribution of shifting unification in Taiwan (2004–2016). Adaoted from “National Chengchi University Election Study Center, TEDS2004P_ind, TEDS2008P_ind, TEDS2012, TEDS2016.” CU-IU male (Compatible unification–incompatible unification Male) is derived by deducting the percentage of men supporting incompatible unification from that of those supporting compatible independence; CU-IU female (Compatible unification–incompatible unification Female) is derived by deducting the percentage of women supporting incompatible unification from that of those supporting compatible independence.

Conclusion

By examining the conflictual evolution of nationalism in Taiwan, this article first reviews the origins of Taiwan’s nationalism and its gendered characteristics, and reveals that the KMT’s nationalist movement right from the beginning infused itself into the daily lives of Taiwanese citizens, perpetuating a gender hierarchy that relegated women to the traditional roles of good mothers and wives, which would serve the KMT’s nationalistic goals. However, as nationalism developed along with modernization in Taiwan, women’s social status and autonomy also improved dramatically. This improvement demonstrates that the link between women and nationalism is not direct but is constantly changing and mediated by other associated events or processes, from the civil war to modernization and democratization.

In the current nationalistic context, which is the main thrust of this article, the mediated issues associated with nationalist discourses in Taiwan are the military threats and economic integration across the Strait. Since the 1990s, on the one hand, any political attempts or moves by Taiwan in the direction of independence have triggered direct or indirect military threats or military actions from China. Surrounded by the constant threat of violence and committed to the ongoing need for a strong defense, Taiwan has elevated its men to roles that are much more central than those occupied by women. Women are therefore more suspicious of the nationalism associated with militarism than are men, a difference that has led women to distance themselves from Taiwan independence, as shown by this study’s survey data. On the other hand, Chinese nationalism has been greatly affected by the growing cross-Strait trade and the growing economic interdependence between the two sides. Since men have more access to and gain more substantial benefits from the economic interactions across the Strait than women, more men have a stronger interest in supporting unification.

This study does not suggest that women ignore nationalism-related issues in Taiwan. It is rather the case that women’s attitudes toward nationalism are shaped by the social constructions embedded within each nationalist discourse. The regulatory processes of the nation-state are by no means static and fixed, but are practiced in multiple ways, including a double process of subordination and contestation (Kaplan et al., 1999, p. 10). The process of national construction is repeatedly a boundary-drawing and differentiating process, determining who “we” are versus who “they” are, distinguishing who is included from who is excluded, and appropriating interest along gendered hierarchical lines. Through the historical and empirical investigation, we reveal how Taiwanese experiences and discourses on nationalism have different impacts on women and men under different conditions, and how the lesser nationalistic inclinations of women have been born out of this gendering process.

Notes

References

-

Achen, C. H., Wang, T. Y., (Eds.) (2017), The Taiwan voter, Ann Arbor, MI, University of Michigan Press.

[https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9375036]

- Blom, I., Hagemann, K., Hall, C., (Eds.) (2000), Gendered nations: Nationalisms and gender order in the long nineteenth century, Oxford, UK, Berg Publishers.

-

Campbell, K. M., Mitchell, D. J., (2001), Crisis in the Taiwan Strait, Foreign Affairs, 80, p14-25.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/20050223]

- Chang, D., (2009), Women’s movement in twentieth-century Taiwan, Urbana and Chicago, University of Illinois Press.

- Chen, C.-J., (2006), Gender and national membership—A feminist legal history of gender and nationality in Taiwan, National Taiwan University Law Journal, 35(4), p1-101, In Chinese.

-

Chen, R-L., (2013), Taiwan’s identity in formation: In reaction to a democratizing Taiwan and a rising China, Asian Ethnicity, 13(2), p229-250.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/14631369.2012.722446]

-

Chu, Y.-H., (2004), Taiwan’s national identity politics and the prospect of cross-Strait relations, Asian Survey, 44(4), p484-512.

[https://doi.org/10.1525/as.2004.44.4.484]

-

Diamond, N., (1975), Women under Kuomintang rule: Variations on the feminine mystique, Modern China, 1(1), p3-45.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/009770047500100101]

- Edwards, L., (2016), International women’s day in China: Feminism meets militarized nationalism and competing party programs, Asian Studies Review, 40(1), p89-105.

- Elshtain, J. B., (1987), Women and war, New York, NY, Basic Books.

- Enloe, C., (1990), Bananas, beaches and bases: Making feminist sense of international politics, Berkeley, CA, University of California Press.

- Farris, C. S., (1994), The social discourse on women's role in Taiwan: A textual analysis, In M. A. Rubinstein, (Ed.)The other Taiwan: 1945 to the present, p305-329, Armonk, NY, M.E. Sharpe.

-

Gallin, R., (1984), Women, family, and the political economy of Taiwan, Journal of Peasant Studies, 12(1), p76-92.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/03066158408438256]

- Gellner, E., (1983), Nations and nationalism, Oxford, UK, Blackwell.

- Goldstein, J. S., (2001), War and gender: How gender shapes the war system and vice versa, Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press.

-

Greenhalgh, S., (1985), Sexual stratification: The other side of ‘growth with equity’ in East Asia, Population and Development Review, 11(2), p265-314.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/1973489]

- Greenhalgh, S., (1988), Intergenerational contrasts: Familial roots of sexual stratification in Taiwan, In D. Dwyer, J. Bruce, (Eds.)A home divided: Women and income in the Third World, p39-70, Stanford, CA, Stanford University Press.

- Hall, C., (1993), Gender, nationalisms, and national identities: Bellagio symposium, Feminist Review, 44, p97-103.

-

Hickey, D., (2013), Wake up to reality: Taiwan, the Chinese mainland and peace across the Taiwan Strait, Journal of Chinese Political Science, 18, p1-20.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-012-9224-0]

- Hsieh, J. F-S., Niou, E. M-S., (2005), Measuring Taiwanese public opinion on Taiwanese independence, The China Quarterly, 181, p158-168.

-

Hynes, H. P., (2004), On the battlefield of women’s bodies: An overview of the harm of war to women, Women’s Studies International Forum, 27, p431-445.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2004.09.001]

- Jayawardena, K., (1986), Feminism and nationalism in the Third World, London, Zed Books.

- Kantola, J., (2016), State/Nation, In L. Disch, M. Hawkesworth, (Eds.)The Oxford Handbook of Feminist Theory, p915-933, Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press.

- Kaplan, C., Alarcon, N., Moallem, M., (Eds.) (1999), Between women and nation: Nationalisms, transnational feminisms, and the state, Durham, NC, Duke University Press.

- Keng, S., (2002, Apr), High-tech entrepreneurs or Taiwanese? The identity of Taiwanese high-tech entrepreneurs in the Greater Shanghai Area, Paper presented at the Conference of Informatics and Politics, Taiwan, Fo-Guang University, In Chinese.

- Keng, S., Chen, L.-H., Huang, K.-P., (2006), Sense, sensitivity, and sophistication in shaping the future of cross-Strait relations, Issues and Studies, 42(4), p23-66.

- Mayer, T., (2000), Gender ironies of nationalism: Sexing the nation, NY, Routledge.

- McClintock, A., (1996), No longer in future heaven: Nationalism, gender and race, In G. Eley, R. S. Grigor, (Eds.)Becoming National: A Reader, p260-284, New York, NY, Oxford University Press.

- Peterson, S. V., Runyan, A. S., (1993), Global gender issues: Dilemmas in world politics, Boulder, Westview Press.

-

Ryan, L., (1997), A question of loyalty: War, nation, and feminism in early twentieth-century Ireland, Women’s Studies International Forum, 20(1), p21-32.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-5395(96)00092-1]

-

Shen, H.-H., (2005), ‘The first Taiwanese wives’ and ‘the Chinese mistresses’: The international division of labour in familial and intimate relations across the Taiwan Strait, Global Networks, 5(4), p419-437.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0374.2005.00127.x]

-

Siegel, M., (2016), Feminism, pacifism, and political violence in Europe and China in the era of the World Wars, Gender & History, 28(3), p641-659.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0424.12243]

- Smith, A., (1986), The ethnic origins of nations, Oxford, UK, Blackwell Publishers.

-

Thapar-Björkert, S., (2013), Gender, nations, and nationalism, In G. Waylen, K. Celis, J. Kantola, S. L. Weldon, (Eds.)The Oxford handbook of gender and politics, p803-827, Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199751457.001.0001]

- Tung, C.-Y., (2002), Taiwan’s reaction to China military threats in 1995–96 and 1999–2000, China Affairs, 9, p71-89, In Chinese.

- Tung, C.-Y., (2003), Cross-Strait economic relations: China’s leverage and Taiwan’s vulnerability, Issues & Studies, 39(3), p137-175.

-

Vickers, J., (2006), Bringing nations in: Some methodological and conceptual issues in connecting feminisms with nationhood and nationalisms, International Feminist Journal of Politics, 8(1), p84-109.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/14616740500415490]

- Walby, S., (1992), Women and nation, International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 33(1/2), p81-100.

- Walby, S., (2006), Gender approaches to nations and nationalism, In G. Delanty, K. Krishan, (Eds.)The Sage handbook of nations and nationalism, p118-128, London, Sage.

- Wang, C.-L., (2002), Flowing home: The homelife and identity of the wives of Taiwanese businessmen in China, Master’s thesis, National Taiwan University, In Chinese.

-

Wang, T. Y., (2017), Changing boundaries: The development of the Taiwan voters’ identity, In C. H. Achen, T. Y. Wang, (Eds.)The Taiwan voter, p45-70, Ann Arbor, MI, University of Michigan Press.

[https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9375036]

- Wang, Z., (1999), Women in the Chinese enlightenment, Berkeley, CA, University of California Press.

- Watanabe, K., (1997), Militarism, colonialism, and the trafficking of women: ‘Comfort Women’ forced into sexual labor for Japanese soldiers, In J. Moore, (Ed.)The other Japan: Conflict, compromise, and resistance since 1945, p305-319, Armonk, NY, M.E. Sharpe.

- Woolf, V., (1963), Three Guineas, Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, Original work published 1938.

- Wu, N.-T., (1992), Party support and national identities: Social cleavages and competition in Taiwan, Bulletin of the Institute of Ethnology Academia Sinica, 74, p33-60, In Chinese.

-

Xu, X., Lai, S.-C., (2002), Resources, gender ideologies, and marital power: The case of Taiwan, Journal of Family Issues, 23(2), p209-245.

[https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X02023002003]

-

Yang, W.-Y., (2016), The China complex in Taiwan: The tug of war between identity and interest, Issues & Studies, 52(1), p1-34.

[https://doi.org/10.1142/s1013251116500028]

- Yang, W.-Y., Liu, J.-W., (2009), Exploring gender differences on attitudes towards Independence/Unification: From the perspectives of peace-war and development-interest, Electoral Studies, 16(1), p37-66, In Chinese.

-

Yeh, H.-Y., (2014), A sacred bastion? A nation in itself? An economic partner of rising China? Three waves of nation-building in Taiwan after 1949, Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism, 14(1), p207-228.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/sena.12074]

- Yoshiaki, Y., (2002), Comfort women: Sexual slavery in the Japanese military during World War II, S. O’Brien, Trans.New York, NY, Columbia University Press.

- Yuval-Davis, N., (1997), Gender and nation, London, Sage.

- Yuval-Davis, N., Anthias, F., (Eds.) (1989), Women-Nation-State, London, Macmillan.

Biographical Note Wan-Ying Yang is the Professor of the Department of Political Science at the National Chengchi University, Taipei, Taiwan. Her research interests focus on the subjects of identity and gender politics, women’s movements, women’s political participation, and gender gaps in political attitudes and behaviors. E-mail: wyyang@nccu.edu.tw